SIZE MATTERS: SEXUAL CANNIBALISM

Whoever authorized the evolution of the spiders of Australia should be summarily dragged out into the street and shot.

Mira Grant, How Green This Land, How Blue This Sea

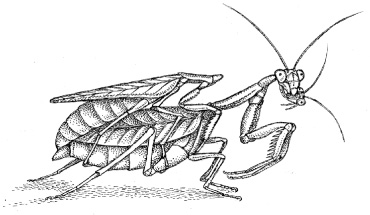

WHILE IT’S FAIRLY COMMON KNOWLEDGE that the praying mantis is the co-holder (along with the black widow spider) of the title Nature’s Most Infamous Cannibal, fewer people realise that the name praying mantis is shared by nearly all of the 2,200 species making up the order Mantodea.

The moniker comes from the curious manner in which the insects hold their forelegs while resting. As a result of this prayer-like attitude they’ve become some of the most popular insects in mythology and folklore. Many of these mantid myths have religious or semi-religious overtones. In France, they’re known as prie dieu and are said to point lost children homeward. The Khoi people of South Africa regard praying mantises as holy, while Arab and Turkish folklore holds that the insects direct their prayers toward Mecca. Americans once believed that praying mantises blinded people and killed horses, this perhaps as a nod to the fact that, rather than being used for prayer, the anterior-most limbs are actually modified into lethal, spike-covered weapons. Often well-camouflaged, most species are ambush predators, lashing out with their ‘raptorial legs’ to capture, crush and secure their prey while a set of sharpened mouth parts slice, can-opener style, through the toughest exoskeleton.

Although mantises feed primarily on other insects, the largest species can reach around six inches in length and these giants will attack and consume small reptiles, birds and even mammals. It is likely that this type of predatory behaviour is responsible for the common misspelling ‘preying mantis’.

As a child in America during the 1960s I was told that there would be a $50 fine for anyone caught killing a praying mantis (and my friends have the same recollections). Since I was unable to uncover a record of any such federal or state law, I can only assume that the story was a scare tactic designed to keep nasty little boys from slaughtering an uncommonly pious insect known to eliminate an array of less religiously inclined pests.

Many people are familiar with the praying mantis’s supposed penchant for cannibalistic sexual encounters, reports of which began showing up in the scientific literature in the late nineteenth century. Back then, several authors claimed that female mantises regularly bit off the triangular heads of their partners during sex. It was claimed that the decapitated males continued to copulate, abdomens pulsing as if nothing much had happened, and several hours later the female would stride off, fully fertilised, leaving the male reduced to a tiny pile of wings. Similar tales about mantid mating continued into the early twentieth century, when members of a new generation of entomologists began investigating this rather puzzling behaviour.

One hypothesis reasoned that this occurred because the male mantis’s brain actually inhibited sexual performance. With their heads removed, however, they became ‘disinhibited’, found the rhythm and eventually delivered a full load of sperm. Others suggested that getting oneself cannibalised made sense for praying mantis males that might have limited opportunities to mate over their lifetime. In these instances there would be selection pressure to fatten up the only female they might ever run into – especially one now carrying their sperm. Furthermore, headless males reportedly produced more sperm than those equipped with heads, leading to more fertilised eggs and more offspring. These accounts contributed to an overall impression that the decapitation of male mantises was a normal and necessary copulatory stage and, soon after, the concept became entrenched in textbooks and popular literature. Unfortunately, most observations of mantis cannibalism were made in laboratory settings and only after females had been deprived of food.

In reality, cannibalism varies across this large and diverse group. The behaviour has gone unobserved in most species, not necessarily because it doesn’t happen, but because it hasn’t been studied. Researchers such as biologists Eckehard Liske and W. Jackson Davis now believe that, rather than being a required component of mating, the consumption of males is more likely to be a foraging strategy employed by hungry females unable to wrap their forelegs around an alternative form of nutrition.

Support for this hypothesis comes from studies on a wide variety of mantis species, including those in which worse-for-wear females exhibited improved body condition following the act of cannibalism, producing larger egg cases and more offspring. And, significantly, well-fed female mantises showed no cannibalistic tendencies during mating encounters.

Before we blame mantid cannibalism on captive conditions or starvation, though, the fact remains that both wild and captive males exhibit extreme caution as a normal preamble to copulation. Depending on the species, the males’ initial approach can vary from the simple (slow and deliberate movement toward the female, followed by a flying leap onto her back) to the more complex (a series of ritualistic movements that include antennal oscillations and abdominal flexing, then a flying leap onto her back). Researchers believe that these movements serve to either circumvent or inhibit the females’ aggressive, predatory response. It is, therefore, extremely unlikely that these forms of cautious behaviour by males would have evolved if there weren’t at least some risk of attack by females.

What about the male’s famous ability to ‘keep the beat’ even after losing its head? Liske and Davis have an explanation for that phenomenon as well. They believe that, rather than acting as a required stimulus for copulation by releasing sexual movements, decapitation artificially induces this process. This would be similar to the way that loping off a chicken’s head artificially induces locomotor movements that can temporarily propel a headless bird around a barnyard. According to these researchers, from an evolutionary perspective, these reflexive abdominal contractions and the subsequent release of sperm may ensure that fertilisation takes place, even if the male is consumed.

AS FOR PRAYING MANTISES, so for certain notorious spiders has truth been masked by myth. After several papers in the thirties and forties reported that some female spiders devoured their mates after copulation, they became widely known as black widows. Although most of the initial observations turned out to be anecdotal, cannibalism and black widows became forever linked. The association continued through the seventies and eighties, even though researchers working with these spiders were beginning to discover that the behaviour was actually a rare occurrence. They determined not only that most male spiders depart unharmed after copulation, but also that some of them lived in the female’s web for several weeks, even sharing her prey.

According to spider expert Rainer Foelix, the supposed aggressiveness of the female spider toward the male is largely a myth, and when a female is ready for mating, there is little danger for the male. However, if a male mistakenly showed up in the web of a hungry female, it would be quite another story.

What makes the black widow’s notoriety even more unjust is the fact that sexual cannibalism has been reported in sixteen out of 109 spider families. But of these sixteen, one of the most interesting examples takes place in the black widow’s Aussie cousin, the redback. In this species, males go to extreme lengths to guarantee not only their own demise but also their consumption.

The redback is common throughout Australia and, in a country renowned for its notorious creatures, it ranks among the most dangerous. The reasons behind their bad reputation start with a neurotoxic bite that can cause severe pain and swelling, and in rare instances seizures, coma and even death. Like the North American black widows, Australian redbacks are often found in close proximity to human residences, especially sheds and garages offering undisturbed areas full of clutter. Presumably because of the abundance of flies, both black widows and redbacks were once common in outhouses, where their fondness for living under toilet seats was almost as unpopular as their habit of biting anything that blocked their escape routes.

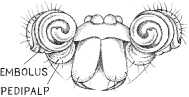

Although encounters with humans are rarely fatal, the same cannot be said for male redback spiders attempting to mate. In the first stage of courtship, the male approaches the female’s web and desperately tries to get her attention (it takes a bit of doing, since he is only about one fifth of her size). He does so by bouncing his body up and down, throwing some silk around and waving his front legs. As a point of information, as well as their eight legs, spiders have an additional pair of anteriorly located appendages called pedipalps. In male spiders, the pedipalps are modified for transferring sperm to the female’s body, necessitated by the fact that spiders lack penises. Furthermore, there is no internal connection between the pedipalps and the testes, which are located within the abdomen. Instead, sperm is initially extruded from a furrow on the male’s abdomen into a spun receptacle called a sperm web. As a male dips his pedipalps into the pooled sperm, a pair of coiled structures called emboli and their associated muscles work like tiny turkey basters to suck up the liquid and store it until copulation.

The next phase of redback courtship begins as the male initiates repeated bouts of physical contact with his potential mate, through a process of tapping, probing and nuzzling. The real heavy petting begins once the male locates the female’s epigynal opening.

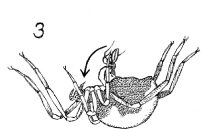

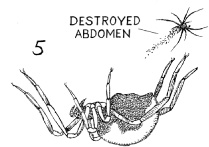

By now, if the female hasn’t already eaten the male (which can put a serious dent in all this foreplay), the spiders briefly assume Gerhardt’s position 3, a sort of missionary position for spiders. Gerhardt’s position 3 appears to be favoured by all Latrodectus species except the Australian redback, where it is abandoned immediately after the male penetrates the female’s epigynal opening with the tip of a sperm-charged embolus. The male then slowly performs a 180° somersault that ends with his abdomen resting against the female’s mouthparts and she immediately expresses her gratitude by vomiting enzyme-laden gut juice onto the tiny acrobat. She then begins to consume the male’s abdomen as they copulate, pausing from time to time to spit out small blobs of white matter. Upon the completion of the sex act, which takes anywhere from five to thirty minutes, the male crawls off a short distance, reportedly making repeated attempts to reel in his spent embolus by stretching it with his forelegs and then releasing it abruptly.

Approximately ten minutes later, rather than fretting over missing body parts, the male returns to the fray, this time wielding the second embolus. The half-eaten spider then proceeds to re-enact its earlier copulatory acrobatics. By way of a ‘welcome back’, the female resumes her meal, consuming more and more of the male’s abdomen. At the end of this, though, rather than allowing him to crawl off, the female wraps her shredded partner in silk, eventually hoovering up his now liquefied innards.

While the benefits of a risk-free meal for the redback mum-to-be are fairly obvious, one has to wonder what is in it for the male, and the mating habits of the redback have indeed puzzled scientists. The only potential answer is that females that had recently eaten their mates were less receptive to the approach of subsequent suitors. Cannibalised males also copulated longer and fathered more offspring than non-cannibalised males. Ultimately, then, it seems that this rather extreme example of paternal investment optimises the likelihood that the cannibalised dad gets to pass his genes on to a new generation.

Things get dicey, though, when trying to determine the benefits for redback males eaten before mating takes place, a situation that has also been reported in orb-weaving spiders like Araneus diadematus. Mark Elgar and zoologist David Nash worked with this species and proposed that pre-mating cannibalism allows females to choose which male will get to inseminate them, with smaller males eaten more often than larger and presumably healthier individuals. The researchers also used modelling studies to propose that pre-mating cannibalism would occur only in instances where there was no shortage of males from which to choose.

Observations related to mantis and spider cannibalism serve to illustrate another of the general rules from Chapter 1: that among invertebrate cannibals, males get cannibalised far more frequently than females. This behaviour occurs particularly in species that exhibit sexual dimorphism, a condition in which there are marked anatomical differences between males and females of the same species.

The most common example of sexual dimorphism is body size, and among invertebrates females are often substantially larger than males. This appears to be related to the ability of larger mothers to better carry, protect and provide for their young. Relatively small body size can also provide males with a biomechanical advantage. Since gravity is less of a constraint on lightweight bodies than on heavier ones, this is especially evident in males that must climb in order to reach females. Likewise, tiny adult male spiders are able to ‘balloon’ like juveniles, using the wind as an energy-efficient means of travel to find a potential mate.

In those rare instances where male spiders are larger than females, the roles of cannibal and cannibalised are also reversed. This occurs in two species that exhibit some very un-spider-like traits. Among sand-dwelling wolf spiders, females undertake risky visits to burrows the larger males have built. Because these structures represent a high reproductive investment, male wolf spiders become extremely picky when females show up and initiate courtship – which they do by waving their forelegs around in the universal signal for ‘Pick me! Pick me!’ In many cases, though, researchers have noted that instead of attracting a mate, the females were often attacked and eaten.

To determine why, arachnologist Anita Aisenberg and her colleagues performed experiments in which twenty male spiders were consecutively exposed to one virgin and one previously inseminated female (in alternating order). Findings revealed that only 10 per cent of the virgin females were cannibalised compared with 25 per cent of the non-virgin females, especially those exhibiting lower body condition indices. In other words, male wolf spiders chose their mates based on looks and sexual history. The researchers concluded that by selecting younger, fitter females, male spiders maximised the likelihood that their mate would survive to produce successful offspring. Older, less fit females also served a purpose: food.

Cannibalism by males also occurs in water spiders, the only living arachnids that exist completely underwater. In this species, females spend most of their lives inside web-shrouded air bells, where their smaller bodies require less oxygen then their male counterparts. Natural selection may favour larger body size in male water spiders by providing them with enhanced swimming and diving abilities. While females are ambush predators, males are active hunters, and although their diets consist primarily of insect larvae, they will kill and devour smaller males during intense competition for mates. The female water spiders’ preference for larger males can also quickly become deadly, specifically during failed mating encounters.

These two examples illustrate that, when cannibalism occurs, it might well be size, rather than sex, that is the key determinant, with the smaller individuals ending up on the menu.

SPIDERS AND PRAYING MANTISES are far from the only animals who engage in cannibalistic copulation. When terrestrial snails cross paths (or, more accurately, slime trails), the potential for bizarre sexual encounters can rival any stag do. For the snails, the high hook-up ratio stems from the fact that most of the participants are simultaneous hermaphrodites, enabling them to exchange sperm while at the same time having their own eggs fertilised. And while this particular sexual orientation increases the likelihood that any two individuals that meet can mate, things can go downhill quickly once the lovers begin biting chunks out of each other.

Snails and slugs, their shell-challenged relatives, are molluscs, a biologically diverse invertebrate group that also contains the bivalves (clams, oysters and their relatives) and cephalopods (squid, octopi and cuttlefish). Known collectively as gastropods, the approximately 85,000 species of snails and slugs have a worldwide distribution, inhabiting a variety of marine, freshwater and terrestrial environments. To put this into perspective, there are approximately seventeen times more gastropod species on the planet than there are mammals.

Gastropods are renowned for their slow-footed locomotion – a point perennially celebrated at snail-racing championships. But what snails may lack in speed, they make up for in other ways: by devoting less energy to locomotion, they can spend more of it involved in alternative behaviour – like mating.

Although snail sex can last for up to six hours in some herbivorous species this is definitely not the case in certain carnivorous gastropods, where foreplay can turn into cannibalism in the blink of a turreted eye. In these species, since even copulating individuals will bite their mates, each potential sexual partner is also a potential predator. As a result, they often employ the wham-bam-scram approach during sexual encounters, which can sometimes linger on for as long as six seconds.

Even more shocking are banana slugs, which become so entwined during sex that they sometimes chew off their partner’s corkscrew-shaped penis in an effort to disengage. During this process, known as apophallation, penises are slurped down spaghetti-style, occasionally by their owners. Although this usually puts an end to the tryst, the fact that the penis does not grow back presents fewer problems than one would expect. The hermaphrodite slugs simply carry on the remainder of their lives as females.

In some land snails, things get bizarre even before copulation starts: partners will shoot calcified ‘love darts’ at each other, an exchange initiated when the body of one snail touches that of a potential mate. This tactile stimulation triggers the release of built-up hydraulic pressure in a sac surrounding the dart. As a result, the barbed projectile (also known as a gypsobelum) explodes outwards, embedding itself in the body wall of the second individual. In most instances, the skewered snail responds by shooting a dart of its own, and mating happens shortly thereafter.

Often, though, the exchange proceeds with something less than textbook precision. Since most snails are nocturnal, their visual systems are basic. They can differentiate between light and dark but an inability to determine details about their slimy targets (or anything else, for that matter) can lead to a serious lack of accuracy. As a result, headshots and similar misfirings are a common occurrence.

But why do some snails fire miniature harpoons at each other at all? The proposed function of this behaviour has undergone some revision. Earlier snail experts thought that love darts were the equivalent of an exchange of wedding gifts – in this instance calcium carbonate, a major component of the snails’ shell and eggs. Another suggestion was that the projectiles might act as an aphrodisiac or that they somehow signalled the shooter’s willingness to mate. But support for these hypotheses never materialised.

I posed the question to McGill University biologist Ronald Chase, whose work in the 1990s helped solve the mystery of this baffling behaviour. ‘The darts serve to increase paternity,’ he told me, since snails scoring love-dart hits on their partners before mating fathered twice as many offspring as those that didn’t hit their targets. The key to the enhanced reproductive effect was apparently the tiny projectile’s chemical coating. Chase and his colleagues showed that this hormone-like substance prevented digestive enzymes from destroying the majority of incoming sperm, something that occurred in non-skewered snails. Spared digestion, the snail sperm sped onward, eventually fertilising a greater number of eggs. A 2013 study by Japanese researchers also showed that snails skewered by love darts delayed re-mating with other individuals, an indication that something in the dart’s mucous coating suppressed subsequent infidelity.

According to Chase, ‘It’s all basically sexual selection.’ In other words, in any given population, some individuals outproduce other individuals because they’re better at securing mates, usually by making themselves more attractive to the opposite sex or by beating back the competition. In land snails, explanations for who got the edge and how they achieved it are confounded just a bit by the fact that mating individuals exchange not only sperm but also explosive projectiles.

Before leaving the topic of snails, if all this talk about love darts has you thinking about one of the most endearing characters of ancient mythology, you aren’t alone. Ronald Chase believes that Cupid, the Roman version of the Greek god Eros, had his origin in land snails and their love darts. According to Chase, the species of snail his group worked on is also found in Greece and – though no tangible evidence has been found – it certainly seems possible that the snails’ romantic habits might have been a source of ancient inspiration for the famous arrow-shooting cherub.