UNDER PRESSURE: STRESS-RELATED CANNIBALISM

Hunger has its own logic.

Bertolt Brecht

OVERCROWDED CONDITIONS have long been known to increase cannibalism, as they often coincide with both hunger and a decrease in the availability of alternative forms of nutrition, a point that will become horribly clear once we begin our investigation of its human variant.

Carrying the banner (albeit a tiny one) for animal cannibalism due to overcrowding are the Mormon crickets. These insects are native to the North American West. Attaining a body length of nearly three inches, Mormon crickets are flightless, but like their winged cousins, the grasshoppers and locusts, they’re renowned for their spectacular swarming behaviour and mass migrations. According to biologist and Mormon cricket expert Stephen Simpson, favourable warm and moist weather conditions in early spring can lead to the nearly simultaneous hatching of several million individuals. Almost immediately, the nymphs begin to march, and they do so in a spectacularly well-coordinated manner, swarming for self-protection.

Seeking to illuminate principles of mass migration and collective behaviour, Simpson and his co-workers conducted food-preference tests on captive Mormon crickets. They determined that protein and salt were the limiting resources being sought by the swarming insect masses. Incidences of cannibalism began soon after these resources were depleted, the nearest source of protein and salt then being a neighbouring cricket. Simpson found that each insect chased the one in front, and was in turn chased by the cricket behind. In such circumstances, stopping to eat becomes risky, requiring individuals to fend off other members of the swarm with their powerful hind legs. ‘Losing a leg is fatal,’ he told me. ‘The weak and the injured are most at risk.’

Simpson demonstrated the vulnerability of the weak and injured by glueing tiny weights to some of the crickets, thus causing them to lag behind their unencumbered swarm-mates. Almost immediately they were attacked and eaten by the hungry horde approaching from behind. In the end, Simpson and his colleagues determined that the massive migratory bands were actually forced marches.

WHILE AVIAN CANNIBALISM might be relatively rare in the wild, once birds are removed from their natural setting and packed shoulder-to-shoulder (or ruffled feather to ruffled feather) it’s a different story. When thousands of stressed-out birds have little to occupy their time, the situation can deteriorate rapidly. In these instances the real meaning of the term ‘pecking order’ becomes gruesomely apparent as some individuals are pecked to death and eaten. Initially, cannibalism on poultry farms was thought to result from a protein-deficient diet, but researchers now believe that it’s actually misdirected foraging related to cramped and inadequate housing conditions.

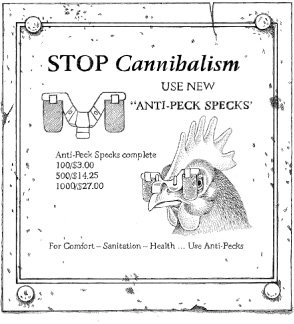

As the poultry and egg industries became established, feather pecking and cannibalism (known in the trade as ‘pick-out’) became two of the most serious threats faced by poultry farmers. To stop cannibalism and prevent the loss of their valuable egg-laying hens, farmers routinely clipped off the tip of the bird’s beak. In the 1940s, however, the National Band and Tag Company came up with a far more humane method to deal with the problem. Their design team reasoned that if the birds couldn’t see ‘raw flesh or blood’ then they wouldn’t cannibalise each other, and so they came up with ‘Anti-peck specks’ – mini-sunglasses equipped with red celluloid lenses and aluminium frames and attached to the upper portion of the bird’s beak near the base. Poultry farmers were informed that having their chickens see the world through rose-tinted glasses would ‘make a sissy of your toughest birds’. Purchased in bulk ($27 per 1,000), apparently they worked.1

Currently, only seventy-five species of mammals (out of roughly 5,700) are reported to regularly practise some form of cannibalism. Although this number will likely increase as more researchers become interested in the topic, the overall low occurrence of cannibalism in mammals is probably related to relatively low numbers of offspring coupled with a high degree of parental care (compared to non-mammals).

The golden hamster, also known as the Syrian hamster, is a popular pet for children but is also known to display some nightmarish behaviour in captivity. The problems stem from major differences between the animals’ natural habitats and the cramped captive conditions under which they are typically held. Native to northern Syria and southern Turkey, the hamster lives in dry, desert environments. Adults are solitary, highly territorial and widely dispersed. Individuals inhabit their own burrows and emerge for short periods at dawn and dusk to feed and mate. This crepuscular lifestyle is thought to help them avoid nocturnal predators like owls, foxes and feral dogs. The results of a study on golden hamsters in the wild emphasised the major differences between natural conditions and those imposed on pet hamsters. For example, the researchers determined that in the wild, the average time hamsters spent on the surface during a twenty-four-hour period was eighty-seven minutes.

The problems between natural and captive conditions often begin in pet shops, where male and female golden hamsters are often kept in unnaturally large groups and displayed in well-lit tanks. They are purchased singly or in pairs. As pets, these desert-dwellers are housed in cages or trendy modular contraptions of translucent plastic tubes linking ‘rooms’. Unfortunately, the cages are often too small and golden hamsters have a hard time fitting through the plastic tubes, especially when pregnant or obese from overfeeding. Cage floors are usually covered in cedar shavings, hardly reminiscent of a desert environment. Regularly handled by children and often subjected to excessive noise and damp conditions resulting from soiled cage bedding or leaky water bottles, many pet hamsters spend their existence under the watchful gaze of dogs and cats: the hamster’s natural enemies.

As a result of this catalogue of stresses in captivity, female golden hamsters, especially younger ones, frequently eat their own pups. Beyond over- or under-feeding and housing conditions, cannibalism can be triggered if hamsters are handled late in their pregnancy or if the babies are handled within ten days of their birth. The presence of additional individuals (even the father) can also lead females to consume their own, and heterocannibalism can occur if adult females encounter unrelated young. However, filial cannibalism can be prevented by isolating pregnant individuals, adequately meeting their nutritional requirements and refraining from handling female hamsters for a fortnight before and after they give birth.

Cannibalism of adults can also take place when several mature golden hamsters are kept in the same cage. This includes siblings, who reach sexual maturity at around four weeks of age. Under these conditions fighting is common, and serious injuries or even fatalities can result. In the latter instances, the survivor typically consumes the carcass of the loser.

Although mice, rats, guinea pigs and rabbits also occasionally cannibalise their young in captivity, primarily when food and water are scarce, there are several factors that appear to make golden hamsters even more prone to do so. Most significant is the fact that the hamster has the shortest gestation period (sixteen days) of any placental mammal and they can become pregnant again within a few days of giving birth. This means that females, already weakened and stressed out by the rigours of pregnancy, delivery and nursing, may be tending a new litter of eight to ten pups less than three weeks after their previous delivery.

When non-human primates are compared with other mammal groups, cannibalism is rare, having been observed in only eleven of 418 extant species, again under unnatural circumstances and often linked to overcrowding. Many examples of primate infanticide and/or cannibalism have been shown to be stress-related. Changes in location or deficient captive conditions play a role in most reports of primate cannibalism, with the latter blamed for incidences of infanticide in bush babies, lemurs, marmosets and squirrel monkeys. In each case, the victims were invariably neonates while the aggressors were either group members or relatives.

However, one primate group in which infanticide and cannibalism are relatively common practices is the chimpanzees. Descriptions of the behaviour among our closest relatives are both chilling and fascinating.

Initially, reports of chimpanzee cannibalism focused solely on adult males, who routinely killed and sometimes consumed infants belonging to ‘strangers’, i.e. adult females from outside their own groups. According to Dr Jane Goodall, female chimpanzees sometimes transferred from one community to another. ‘A female who loses her infant during an encounter with neighbouring males is likely to come into oestrus within a month or so and would then, theoretically, be available for recruitment into the community of the aggressors.’ This behaviour is also seen in some types of bears and big cats.

Other attacks by male chimps on infant-bearing females occurred during ‘inter-community aggression’, for example when groups of male chimpanzees patrolling the outer edges of their territories encountered individuals from adjacent communities.

Then, in 1976, Goodall reported on three observations in which two female chimps were involved in within-group infanticide and cannibalism in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park. What made these attacks unique was the absence of male involvement. Stranger yet was the fact that the individuals involved were a mother (Passion) and daughter (Pom) whose seemingly premeditated approach to somewhere between five and ten infant-bearing females provided researchers with a grim explanation for previously unexplained infant disappearances. Goodall believes that the attacks on the mothers functioned solely as a means to acquire food, since once they had established their claim over their prey they made no further aggressive attacks on the mothers.

Thirty years later, similar attacks by female chimp coalitions against infant-bearing mothers were observed in Uganda’s Budongo Forest. A team led by comparative psychologist Simon Townsend concluded that the lethal attacks were triggered by an influx of females, leading to overcrowding and subsequent increased competition for resources.

Although acts of cannibalism in chimpanzees are not everyday occurrences, some researchers have suggested that the encroachment of humans into the areas surrounding preserves inhabited by chimps will eventually lead to population density issues and more competition for dwindling resources. If this occurs, incidences of cannibalism by our closest relatives may be expected to increase.

Footnote

1 Although Anti-peck specks are now collectors’ items, the idea behind them lives on in plastic clips called ‘Peepers’, which can be attached via a pin through the nostrils of various commercially raised game birds.