SKIN DEEP: THE WEIRD WORLD OF CAECILIAN CANNIBALISM

Cannibalism is found in over 1,500 species.

Anthropophagusaphobia (fear of cannibals) is found in only one.

Which one seems unnatural now?

Unattributed internet picture caption

IS EATING ONE’S OWN FINGERNAILS or mucus an example of auto-cannibalism? And what about breast-feeding? Is this type of parental care yet another form of cannibalism? These are examples of the grey area between what most people consider cannibalism and other forms of behaviour.

Like breast-feeding, the following example is a form of parental care, but one that extends further into the realm of cannibalistic behaviour. It occurs in the Caecilians, a small order of not-very-obvious amphibians, whose legless bodies often get them mistaken for worms or snakes. Caecilians inhabit tropical regions of Central and South America, Africa and Southern Asia – a neat trick that lends support to the theory of continental drift. (Although some caecilians are aquatic, it is not believed that their ancestors were strong enough swimmers to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Instead, prehistoric caecilians were likely separated when the current continents of South America and Africa split apart between 100 and 130 million years ago.)

They also serve as great examples of convergent evolution, in which unrelated organisms evolve similar anatomical, physiological or behavioural characteristics because they inhabit similar environments. As a result of their subterranean lifestyles, caecilians share a number of anatomical similarities with moles and mole rats. In each, the eyes are either set deeply into the skulls or covered by a thick layer of skin, and as a consequence they are nearly blind.

Caecilians possess a pair of short ‘tentacles’ located between their nostrils and eyes. These chemosensors enable the subterraneans to ‘taste’ their environments without opening their mouths as they burrow through the soil or leaf litter in search of insects and small vertebrates. Similar sensory structures can be seen in other burrowing creatures, most notably the aptly named star-nosed mole.

Significantly, as a group, caecilians exhibit a fair degree of reproductive diversity. Approximately half of the 170 species are egg layers, and hatchlings either resemble miniature versions of their parents or pass through a brief larval stage. Other species are viviparous, giving birth to tiny, helpless young.

All caecilians do share one characteristic, namely, internal fertilisation, and during this process sperm is deposited into the female’s cloaca by the male with the aid of a unique, penis-like structure called a phallodeum. In many vertebrates, the cloaca is a single opening shared by the intestinal, reproductive and urinary tracts.

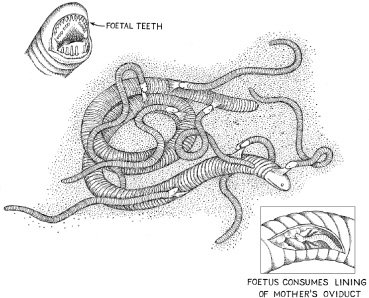

Information about caecilian cannibalism first began emerging from Marvalee Wake’s lab at the University of California, Berkeley. The herpetologist was looking at foetal and new-born individuals from several viviparous species and began investigating the function of their peculiar-looking baby teeth, known to scientist-types as deciduous dentition.

While some of the teeth were spoon-shaped, others were pronged or resembled grappling hooks, but none of them resembled adult teeth. Wake also performed a microscopic comparison of caecilian oviducts. She observed that in pregnant individuals, the inner lining of the oviduct was thicker and had a proliferation of glands, which she referred to as ‘secretory beds’. These glands released a substance that fellow researcher H. W. Parker had previously labelled ‘uterine milk’. He described the goo, which he believed the foetuses were ingesting, as ‘a thick white creamy material, consisting mainly of an emulsion of fat droplets, together with disorganised cellular material’. Parker also thought that the caecilians’ foetal teeth were used only after birth, as a way to scrape algae from rocks and leaves. Wake, however, had her doubts, especially since she noticed that these teeth were resorbed before birth or shortly after.

Pressing on with her study, Wake saw something odd. In sections of oviduct adjacent to early-term foetuses, the epithelial lining was intact and crowded with glands, while in females carrying late-term foetuses the lining of the oviduct was completely missing here, although it was intact in regions further away. Wake proposed that foetal caecilians used their teeth before birth to scrape fat-rich secretions and cellular material from the lining of their mother’s oviduct. Although this couldn’t be seen directly, she had gathered circumstantial evidence in the form of differences in the oviduct between early-term and late-term individuals. After an analysis of foetal stomach contents revealed cellular material, Wake had enough evidence to conclude that caecilian parental care extended beyond the production of uterine milk and into the realm of cannibalism. Unborn caecilians were eating the lining of their mothers’ reproductive tracts.

But if the consumption of maternal cells gave this admittedly strange behaviour a cannibalistic slant, it was in the egg-laying species that the story really took off.

In 2006 Alexander Kupfer, Mark Wilkinson and their co-workers were studying the oviparous African caecilian Boulengerula taitanus when they made a remarkable discovery. This species had been previously reported to guard its young after hatching and the researchers wanted to examine this behaviour in greater detail. They collected twenty-one females and their hatchlings, and set them up in small plastic boxes designed to resemble the nests they had observed in the field. Their initial observations included the fact that the mothers’ skin was much paler than it was in non-mothers and that hatchlings also had a full set of deciduous teeth.

Intrigued, the researchers set out to film the parental care that had been briefly described by previous studies. On multiple occasions Kupfer and Wilkinson observed a female sitting motionless while the newly hatched brood, consisting of between two and nine young, slithered energetically over her body. Looking closer, they noticed that the babies were pressing their heads against the female’s body, then pulling away with her skin clamped tightly between their jaws. As the researchers watched, the baby caecilians peeled the outer layer of their mother’s skin like a grape … and then consumed it.

Scientists now know that these bouts of ‘dermatophagy’ recur on a regular basis and that the mothers’ epidermis can serve as the young caecilians’ sole source of nutrition for several weeks. Female caecilians are able to endure multiple peelings because their skin grows back at a rapid rate.

‘The outer layer is what they eat,’ Wilkinson said. ‘When that’s peeled off, the layer below matures into the next meal.’

In addition to the ability of the skin to quickly repair and replenish itself, the nutritional content of this material is yet another interesting feature in this bizarre form of parental care. The outermost epidermal layer, the stratum corneum, is usually composed of flattened and dead cells whose primary functions are protection and waterproofing. But when the researchers examined the skin of brooding female caecilians under the microscope they noticed that the stratum corneum had undergone significant modification. The layer was not only thicker but also heavily laden with fat-producing cells, which explained why the baby caecilians experienced significant increases in body length and mass during the week-long observations. It also explained why mothers of newly hatched broods experienced a concurrent decrease in body mass of 14 per cent. In short, dermatophagy is a great way to fatten up the kids but for mums on the receiving end of their gruesome attentions, the price is steep.

Scientists now believe that the presence of dermatophagy in both South American and African oviparous species offers strong support for the hypothesis that these odd forms of maternal investment originally evolved in the egg-laying ancestor of all modern caecilian species. Consequently, when the first live-bearing caecilians evolved, their unborn young were already equipped with a set of foetal teeth, which took on a new function, allowing them to tear away and consume the lining of their mothers’ oviducts.