US AND THEM: EARLY HUMANS AND NEANDERTHALS

Here is a pile of bones of primeval man and beast all mixed together, with no more damning evidence that the man ate the bears than that the bears ate the man – yet paleontology holds a coroner’s inquest in the fifth geologic period on an ‘unpleasantness’ which transpired in the quaternary, and calmly lays it on the MAN, and then adds to it what purports to be evidence of CANNIBALISM. I ask the candid reader, Does not this look like taking advantage of a gentleman who has been dead two million years …

Mark Twain, Life As I Find It

IN 1856, THREE YEARS before publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, a worker at a limestone quarry near Düsseldorf, Germany, uncovered the bones of what he thought was a bear. He gave the fossils to an amateur palaeontologist, who in turn showed them to Dr Hermann Schaaffhausen, an anatomy professor at the University of Bonn. The bones included fragments from a pelvis as well as arm and leg bones. There was also a skullcap – the section of the cranium above the bridge of the nose. The anatomist immediately knew that while the bones were thick and strongly built, they had belonged to a human and not a bear. They were, though, unlike any human bones he had ever seen. Beyond the robust nature of the limbs and pelvis, the skullcap had a low receding forehead and a prominent ridge running across the brow. These anatomical differences led him to conclude that these were the remains of a ‘primitive’ human, ‘one of the wild races of Northern Europe’.

The next year they announced the discovery in a joint paper, but the excitement they hoped to generate never materialised. This was, after all, a scientific community that had yet to reject the concept that organisms had not changed since God created them only five thousand years earlier. It was no real surprise then, when a leading pathologist of the day examined the bone fragments and pronounced them to be modern in origin, insisting that the differences in skeletal anatomy were pathological in nature, having been caused by rickets, a childhood bone disease. He blamed the specimen’s sloping forehead on a series of heavy blows to the head.

By the early 1860s, following the publication of On the Origin of Species, there was increased interest in evolution, especially the topic of human origins. Now the concept of ‘change over time’ was no longer alien and in the newly minted Age of Industry, the idea of the survival of the fittest was not only palatable but also profitable. By 1864, the rickets/head-injury hypothesis had been overshadowed by the discovery of new specimens with identical differences in skeletal structure. ‘Neanderthal man’ became the first prehistoric human to be given its own name, a moniker derived from the Neander river valley, where the presumed first fossils had been uncovered.1

Thrust into the scientific and public eye, Neanderthal man became a Victorian-era sensation. Scientists like Darwin’s contemporary and friend Thomas Huxley believed these particular remains were important because they established a fossil record for humans that supported Darwin’s newly published theory. With none of his friend’s famous restraint, Huxley announced that Homo sapiens had descended with modification from ape-like ancestors and the Neanderthals were just the proof he needed.

Huxley’s rationale was that, although Neanderthals shared many characteristics with modern humans, they also exhibited primitive traits, thus serving as physical evidence that humans, like other organisms, had evolved gradually and over a vast time frame. Neanderthals, he reasoned, were a part of Darwin’s branching evolutionary tree, with this particular branch leading to modern humans.

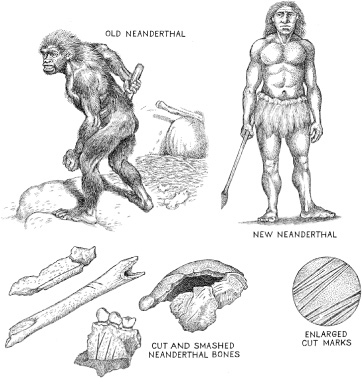

The most serious argument against Huxley’s hypothesis was put forth in 1911. Pierre Marcellin Boule, a French anthropologist and scientific heavyweight, had been called upon to study and reconstruct a Neanderthal specimen that had been uncovered in France several years earlier. Once Boule was finished, anyone viewing the reconstruction would come away with some strong ideas about what Neanderthals looked like. Significantly, he gave the skeleton a curved rather than upright spine, indicative of a stooped, slouching stance. With bent knees, flexed hips and a head that jutted forward, Boule’s Neanderthal resembled an ape. The anthropologist also claimed that the creature’s intelligence matched its ape-like body.

Boule commissioned an artist to produce an illustration of his reconstruction and the result depicted a hairy, gorilla-like figure with a club in one hand and a boulder in the other. The creature stood in front of a nest of vegetation, another obvious reference to gorillas. Boule’s vision of Neanderthals, with their knuckle-dragging posture and ape-like behaviour, also left an indelible mark on a public eager to hear about its ancient ancestors. For decades to come, Neanderthals would become poster boys for stupidity. The epitome of a shambling, dim-witted brute, ‘Neanderthal’ became synonymous with ‘bestial’, ‘brutal’, savage’ and ‘animal’.2 In ‘The Grisly Folk’, a short story written by H. G. Wells in 1921, the author stuck to the Boule party line, depicting ‘Neandertalers’ as cannibalistic ogres: ‘…when his sons grew big enough to annoy him, the grisly man killed them or drove them off. If he killed them he may have eaten them.’ According to Wells, the grisly men also developed a taste for the modern humans who had moved into the neighbourhood, finding ‘the little children of men fair game and pleasant eating’. Because of this type of behaviour (‘lurking’ was also a popular activity), Wells felt that the ultimate extermination of the Neanderthals was completely justified, allowing modern humans to rightfully inherit the Earth.

The only problem with Wells’s character, according to palaeontologist Niles Eldridge, was that it was based on Boule’s misconceptions. ‘Every feature that Boule stressed in his analysis can be shown to have no basis in fact.’

Since the early twentieth century, Neanderthals have undergone a further series of transformations and today there are two main hypotheses.

That they were our direct ancestors (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) became part of what is known as the Regional Continuity hypothesis. It is a view currently supported by palaeoanthropologist Milford Wolpoff, who believes that Neanderthals living in Europe and the Middle East interbred with other archaic humans, eventually evolving into Homo sapiens. According to Wolpoff, similar regional episodes took place elsewhere around the globe as other archaic populations intermingled, hybridising into regional varieties and even subspecies of humans. Importantly, though, there would be enough intermittent contact between these groups (Asians and Europeans, for example) so that only a single species of humans existed at any given time.

The Out of Africa hypothesis holds that modern humans evolved once, in Africa, before spreading to the rest of the world, where they displaced, rather than interbred with, Homo neanderthalensis and others who had been there previously. The groups driven to extinction by Homo sapiens had themselves evolved from an as of yet undiscovered species of Homo (perhaps H. erectus) that had originated in Africa and migrated out earlier.

But whatever hypothesis anthropologists choose to support concerning interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans, and the ultimate demise of the former, Neanderthals are no longer depicted as knuckle-dragging brutes. Instead, studies have shown that they were highly intelligent, with some specimens exhibiting a brain capacity 100–150ml greater than the 1,500ml capacity of modern humans! Researchers have also learned that Neanderthals used fire, wore clothing and constructed an array of stone tools, including knives, spearheads and hand axes.

The possibility that Neanderthals practised cannibalism was briefly argued in 1866 and again in the 1920s, after a fossil skull discovered in Italy was observed to have a gaping hole above and behind the right eye. The wound was initially interpreted as evidence that the skull had been broken open by another Neanderthal intent on extracting the brain for food, but researchers now believe that a hyena caused the damage.

More recent and significantly stronger evidence for Neanderthal cannibalism came from multiple sites in northern Spain, south-eastern France and Croatia. In each instance Neanderthal bones exhibited at least some of the characteristics interpreted by anthropologists as ‘patterns of processing’. This term refers to the telltale damage found on the bones of animals that have been consumed by humans. This Neanderthal-inflicted damage includes some combination of cut marks, which result when a blade is used to remove edible tissue like muscle; signs of gnawing or peeling; percussion hammering (abrasions or pits that result from the bone being hammered against some form of anvil); burning; and the fracturing of long bones, presumably to access the marrow cavity.

But even when these patterns of processing are observed, researchers must proceed with caution before making claims about the occurrence of cannibalism. While these forms of bone damage can be strong indicators of human activity, they can also result from human behaviour or phenomena completely unrelated to cannibalism. According to anthropologist Tim White, ‘Bodies may be buried, burned, placed on scaffolding, set adrift, put in tree trunks or fed to scavengers. Bones may be disinterred, washed, painted, buried in bundles or scattered on stones.’ In what’s called secondary burial, bodies that have already been buried or left to decompose are disinterred and subjected to additional handling. For the ancient Jews this involved placing the bones into stone boxes called ossuaries. For some Australian aboriginal groups and perhaps the ancient Minoans, secondary burial practices included the removal of flesh and cutting of bones. Rituals like these make it extremely difficult to distinguish between funerary rites and cannibalism, especially if the rites are no longer practised or if the group in question no longer exists.

Cut marks on bones may be the result of violent acts related to war or murder. If you can imagine someone unearthing the skeleton of a soldier killed by a bayonet or sword, they might misinterpret the cut marks on the bones as evidence of cannibalism.

Clearly, then, blade marks and other damage inflicted on Neanderthals by fellow Neanderthals and other ancient human groups may have been caused by a variety of actions. Archaeologists now consider this type of bone damage to be strong evidence for cannibalistic behaviour only when it can be matched to similar damage found on the bones of game animals uncovered at the same site. The implication is that if animal and human bodies were processed in the same manner, and if the remains were discarded together, it is reasonably certain that cannibalism took place.

This appears to have been precisely what happened at a Neanderthal cave site known as Moula-Guercy, in south-eastern France. An excavation begun there in 1991 revealed the remains of six Neanderthals and at least five red deer that date to approximately 100,000 years ago. The bones were distributed together and butchered in a similar fashion. The long bones and skulls were smashed and telltale cut marks on the sides of the skulls indicated that the large jaw closure muscles had been filleted. There were also characteristic patterns of modification on the lower jaws, providing evidence that the tongues had been removed. Both Neanderthal and deer bones also exhibited peeling and percussion pits. Lastly, there were distinctive patterns of cuts indicating that bodies from both species had been disarticulated at the shoulder, a process that would have made carrying and handling easier. According to Tim White, ‘The circumstantial forensic evidence [for cannibalism at Moula-Guercy] is excellent.’

Of course, there is always the possibility that this type of damage to the animal bones took place during butchery but that the same types of stone tools were also used to deflesh and disarticulate human remains during non-cannibalistic mortuary practices. As in the case of dinosaurs, the only definitive evidence for prehistoric cannibalism would be the discovery of human remains inside fossil faeces or inside a human stomach.

But among anthropologists, even this type of evidence sparked a controversy.

In 2000, researchers working in the Four Corners region of the American south-west reported that human myoglobin (a form of haemoglobin found in muscles) had been identified from a single fossilised coprolite described as being consistent with human origin. The petrified faeces had evidently been deposited onto a cooking hearth belonging to archaic Puebloans (Anasazi) sometime around ce 1150. Together with defleshed human bones and butchering tools coated with human blood residue, the thirty-gram faecal fossil was used to support the claim that cannibalism had taken place at the south-western Colorado site known as Cowboy Wash. It is a finding that has been the subject of considerable debate, with some researchers insisting that the bone and blood evidence could also have resulted from corpse mutilation, ritualised executions or funerary practices.

These scientists also point out that, while the myoglobin in the coprolite was certainly human in origin, the animal that produced the faeces was never positively identified. This raises the possibility that a coyote or wolf consumed part of a corpse and subsequently defecated in the abandoned cooking hearth.

Even with a set of palaeoanthropological safeguards in place, mistakes can still occur. ‘In many cases you’re finding bones in the normal palaeontological environment,’ renowned American Museum of Natural History palaeontologist Ian Tattersall explained. ‘That is to say, they’ve all been scattered and they’ve been concentrated by water or whatever’s happened to them, which had nothing to do with the actual human activities that may or may not have been carried out after they were deceased.’

To envision how this ‘scattering’ or concentration of fossils can occur, picture a stream cutting through a fossil-containing layer of rock. As the stream walls gradually wear away, fossils are exposed, washed out and deposited into the streambed randomly and over time. Similarly, different parts from the same organism might be exposed at different times, which can also lead to fragments from a single individual being scattered across a wide area.

This water-assisted movement can also take place before the specimens are fossilised. For example, the bodies of creatures that died along an ancient body of water (or in it) may have been carried away by currents and deposited together by gravity. If sediments covered the bodies rapidly enough they may have become fossilised, but their final location may have little or no relevance to what took place when the organisms were alive. For this reason, archaeologists must be cautious when animal and human bones are found mixed together, as it does not necessarily prove that humans did the mixing.3

One instance in which the evidence for human cannibalism remains solid involves Homo antecessor (‘pioneering man’), the reputed ancestor of Neanderthals. The first fossils of this species were uncovered in the 1980s in Atapuerca, a region in northern Spain. Spelunkers found the bones of extinct cave bears at the bottom of a narrow fifty-foot-deep pit. Excavation of the pit, now known as Sima de los Huesos (the Pit of Bones), was initiated in 1984 by palaeontologist Emiliano Aguirre. After his retirement, Aguirre’s students continued to work at the site and in 1991 they began emerging from the stifling heat and claustrophobic conditions with well-preserved hominid bones.

Since then, the site has yielded over 5,000 bone fragments from approximately thirty humans of varying age and sex. The researchers noted that some aspects of the skull and post-cranial skeleton appeared to be Neanderthal-like (including a large pelvis that someone christened ‘Elvis’). Eventually, though, the remains from Atapuerca exhibited sufficient anatomical differences from Neanderthals to warrant placing them into a separate species.

According to Ian Tattersall, Homo antecessor was ‘almost Neanderthal but not quite … they were on the way to becoming Neanderthals.’ To the surprise of researchers, the remains of Homo antecessor recovered from Sima de los Huesos were dated to a minimum of 530,000 years, indicating that the Neanderthal lineage had been in Europe 300,000–400,000 years before the first Neanderthals – far longer than anyone had imagined.

By 1994, researchers were claiming that Homo antecessor remains showed evidence of having been cannibalised. In this case, the fracture patterns, cut marks and tool-induced surface modification were identical to the damage found on the bones of non-human animals that had presumably been used as food. All of the bones (human and non-human) were randomly dispersed as well. The researchers at Atapuerca concluded that the H. antecessor remains came from ‘the victims of other humans who brought bodies to the site, ate their flesh, broke their bones, and extracted the marrow, in the same way they were feeding on the [animals] also preserved in the stratum.’

Interestingly, the presence of so many types of game animals led the same researchers to suggest that Atapuerca did not represent an example of stress-related survival cannibalism, and Ian Tattersall agreed. ‘Sometimes the environment was pretty rich and you wouldn’t necessarily need to practise cannibalism to make your metabolic ends meet, as it were.’ It would be relatively easy to find alternative sources of protein.

Accordingly, the Neanderthal ancestors living at Atapuerca were likely not prehistoric versions of the group of nineteenth-century pioneers known as ‘the Donner Party’ (of whom more later) – stranded in horrible conditions and compelled by starvation to consume their dead. Instead Homo antecessor, like many species throughout the animal kingdom, may have simply considered others of their kind to be food. In other words, they may have eaten human flesh because it was readily available and because they liked it.

No one is absolutely certain when the transition from Homo antecessor to Neanderthal man took place, but it probably happened sometime around 150,000 years ago. If one does not subscribe to the idea that Neanderthal genes were eventually overwhelmed through interbreeding with their more intelligent cousins, then Homo neanderthalensis appears to have gone extinct approximately 30,000 years ago.

Ian Tattersall explained, ‘Neanderthals and modern humans managed to somehow partition the Near East among themselves for a long, long period of time, at a time when modern humans were not behaving like they do today. They left no symbolic record [e.g. depictions of their behaviour and beliefs]. As soon as they started leaving a symbolic record, the Neanderthals were out of there.’

The significance of this, he explained, was that by the time the Neanderthals’ homeland in Europe was invaded by modern humans, humans were behaving in the modern way and had become insuperable competitors.

Given what we know about modern humans and their treatment of the indigenous groups they encounter, it’s difficult to argue against Tattersall’s conclusions. In all likelihood, the Neanderthal homeland was indeed invaded by an advanced, symbolism-driven species, and, as we’ll see in the following chapter, it would have been more of a surprise if Homo sapiens hadn’t raped, enslaved, and slaughtered the Neanderthals and other groups they encountered there.

Footnotes

1 In the early twentieth century, ‘thal’, the German word for ‘valley’, was changed to ‘tal’. As a consequence, ‘Neandertal’ is a common alternative to ‘Neanderthal’. Since the scientific name for the species (or subspecies) remained Homo neanderthalensis, most scientists do not use the new spelling. Soon after the name was coined, researchers determined that two other collections of strange bones found decades earlier in Belgium and Gibraltar (and unnamed by those who discovered them) were also the remains of Neanderthals.

2 Today, even among scientists and academics, calling someone a Neanderthal rarely implies that we’re referring to a skilled hunter who uses his oversized brain to fashion and employ an array of sophisticated tools.

3 Similarly, cave collapses also appear to have caused the demise of a number of Neanderthals whose fossilised bones were initially thought to exhibit percussion pits.