MYTHS OF THE OTHER: COLUMBUS, CARIBS AND CANNIBALISM

DURING HIS SECOND VOYAGE to the New World in 1493, Christoffa Corombo (aka Christopher Columbus) was accompanied by Dr Álvarez Chanca, a physician from Seville, who offered this description of events, after the landing party entered a small village on the island Columbus would name Santa María de Guadaloupe.

The captain … took two parrots, very large and very different from those seen before. He found much cotton, spun and ready for spinning; and articles of food; and he brought away a little of everything; especially he brought away four or five bones of the arms and legs of men. When we saw this, we suspected that the islands were those islands of the Caribe, which are inhabited by people who eat human flesh …

Before Columbus had begun his investigations, the local inhabitants had already fled in terror, leaving behind everything they owned. It was a response that had taken them a little over a year to learn.

During his first voyage in 1492, Columbus referred to all of the native people as ‘Indios’, but by a year later a distinction had been made between the peaceful Arawaks (also called Tainos) and another group known to the locals as the Caribes (or more commonly, Caribs). What Columbus would never know was that the indigenous inhabitants were actually a diverse assemblage that had been living on the islands for hundreds of years. Their ancestors had set out from coastal Venezuela, where the outflowing currents of the Orinoco river carried the migrants into the open sea and far beyond. At each island stop these settlers developed their own cultures and customs, so that by the time the Spaniards arrived, the entire Caribbean island chain had already been colonised, with settlements extending as far north as the Bahamas.

Columbus, though, cared little about local customs or history. Instead, he noted that the Arawaks were gentle and friendly, and he wasted little time in passing this information on to his royal backers in Spain, ‘[The Arawaks] are fitted to be ruled and to be set to work, to cultivate the land and do all else that may be necessary …’

Although no one is quite sure who was doing the translating, soon after his initial arrival the Arawaks reportedly told Columbus that the Caribs inhabited certain of the southern islands, including those that would eventually be called St Vincent, Dominica, Guadeloupe and Trinidad. Columbus was informed that the Caribs were infamous not only for brutal raids against their peaceful neighbours – but also for their unsettling habit of eating their captives. But these were not the Caribs’ only vices. Each year they would meet up with a tribe of warrior women. These fighting females were reportedly ‘fierce to the last degree, strong as tigers, courageous in fight, brutal and merciless’.

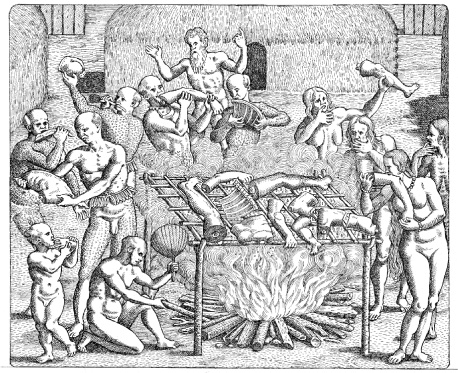

With more than a fleeting resemblance to a fictional race of Amazons dreamed up by the ancient Greeks, these warrior women lived on their own island (Martinique) and killed any men they encountered … except, that is, for the Caribs, who got a yearly invite to drop by for feasting and debauchery. Possibly the invitations stemmed from the fact that the Caribs were renowned for their cooking ability – preparing their viands by smoking them slowly on a wooden platform. It was a setup the Spanish began referring to as a barbacoa. After manning the grill and servicing the gals, the Caribs returned home, taking with them any new-born males who had shown up nine months after the previous year’s party. Female babies would, of course, remain behind to be raised as warriors.

In retrospect, it is difficult to determine where Arawak tall tales ended and Columbus’s vivid and self-serving imagination kicked in. What is known is that European history and folklore were already rich with references to encounters with bizarre monsters and strange human races. Although most of the stories emerging from the New World were greeted with enthusiasm back in Seville, some of Columbus’s patrons expressed scepticism after hearing that the Caribs also hunted with schools of fish. These had been trained to accept tethers and dispatched with instructions to latch on to sea turtles, which could then be reeled in for butchering.1

Easier to accept, perhaps, were Columbus’s claims that some Caribs had dog-like faces, reminiscent of the Cynocephali described nearly 1,400 years earlier by Pliny the Elder, the Roman author and naturalist. Still other New World locals were said to possess a single, centrally located eye or a long tail, an appendage that necessitated the digging of holes by its owner in order to sit down. These creatures were considered to be anything but a joke since, as late as 1758, Linnaeus’s opus Systema Naturae listed three species of man: Homo sapiens (wise man), Homo troglodytes (cave man) and Homo caudatus (tailed man).

But whether or not these strange savages had tails (and even if they were supported by trained fish and Amazonian girlfriends), plans were soon being formulated to pacify the Caribs, who were now being referred to as Canibs. According to scholars, the transition from Carib to Canib apparently resulted from a mispronunciation, although in light of stories describing locals as having canine faces, ‘Canib’ may also be a degenerate form of canis, the Latin for dog. Eventually canib became the root of ‘cannibal’, which replaced anthropophagi, the ancient Greek mouthful previously used to describe people eaters.

But whatever the locals were called, and whatever the origins of the term, the first part of Columbus’s grand plan centred on relieving them of the abundant gold he was convinced they had in their possession. One reason for Columbus’s certainty on this point was the commonly held belief that silver formed in cold climates while gold was created in warm or hot regions. And considering the heat and humidity of the New World tropics, this could only mean that there would be plenty of it around.

Unlike his first voyage, which consisted of three ships and 120 men, Columbus’s second visit to the New World was more of a military occupation force. Accompanying him were seventeen ships and nearly 1,500 men, many of them heavily armed. Although he had begun to look at slave raiding as a means to finance his voyages, his prime directive was to find gold – and lots of it. To facilitate the collection of this massive treasure, he levied tribute on those living in regions like El Cibao, in what is now the northern part of the Dominican Republic. His orders stated that every male between fourteen and seventy years of age was to collect and hand over a substantial measure of gold to his representatives every three months. Those who failed at what quickly became an impossible task had their hands hacked off. Anyone who chose to flee was hunted down – the Spaniards encouraging their vicious war-dogs to tear apart any escapees they could run to ground.

In the end, very little of the precious metal was turned in. Presumably the island residents, under the very real threat of losing their limbs or being eaten alive by giant dogs, quickly ran through any gold they might have had on hand. Since it played only a minor role (or none at all) in their traditions, in all likelihood the locals just didn’t know where to find it – especially in the quantities demanded by the Spanish invaders.

Deeply disappointed at the meagre results, Columbus penned a letter to his royal supporters in Spain in May 1499. In it he wondered ‘why God Our Lord has concealed the gold from us’. There is no record of a response, but Columbus soon refocused his efforts toward the collection of a resource that was available in great supply – humans.

In 1503 this bloodthirsty new take on the exploration of the New World got a significant boost when the self-proclaimed Admiral of the Ocean Sea received a royal proclamation from Queen Isabella. In it she stated that those locals who did not practise cannibalism should be free from slavery and mistreatment. More significantly, though, she also instructed Columbus and his men about what they could do to them if they were determined to be cannibals:

…if such cannibals continue to resist and do not wish to admit and receive to their lands the Captains and men who may be on such voyages by my orders nor to hear them in order to be taught our Sacred Catholic Faith and to be in my service and obedience, they may be captured and taken to these my Kingdoms and Domains and to other parts and places and be sold.

This new position was supported by the Catholic Church several years later, when Pope Innocent IV decreed in 1510 not only that cannibalism was a sin, but also that Christians were perfectly justified in doling out punishment for cannibalism through force of arms.

What happened next was as predictable as it was terrible. On islands where no cannibalism had been reported previously, man-eating was suddenly determined to be a popular practice. Regions previously inhabited by peaceful Arawaks were, upon re-examination, found to be crawling with man-eating Caribs, and very soon the line between the two groups was obliterated. ‘Resistance’ and ‘cannibalism’ became synonymous, and anyone acting aggressively towards the Europeans was immediately labelled a cannibal.

In an effort to organise the cannibal pacification efforts, Rodrigo de Figueroa, the former Governor of Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), was given the job of making judgements on the official classification of all the indigenous groups encountered by the Spanish during their takeover. Testimonials and other ‘evidence’ were used to place the cannibalism tag on island populations, and by a strange coincidence the designations seemed to change with the priorities of the Spanish for the islands in question. Trinidad, for example, was declared a cannibal island in 1511 but the ruling was changed in 1518. Rather than relating to concerns over the welfare of the local people, though, the reclassification came about because of reports of gold in Trinidad and the Spaniards’ desire to maintain the local population for use in mining operations. It was more than coincidental, then, that once the Spanish mining efforts on Trinidad failed to produce any gold, word began filtering in that the locals were cannibals after all. Soon after, the order was given to colonise Trinidad and to depopulate it of its remaining man-eating inhabitants. As a result, the pre-Columbian indigenous population in Trinidad (estimated to be somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 individuals) dropped to half that number within a century.

Even in places that hadn’t initially been designated as cannibal islands, populations dropped precipitously as the locals were either hauled off to toil as slaves, murdered, or died from newly arrived diseases like measles, smallpox, and influenza (the latter may have been a form of swine flu carried by some pigs that Columbus had picked up on the Canary Islands during the early part of his second voyage). According to historian David Stannard, ‘Wherever the marauding, diseased, and heavily armed Spanish forces went out on patrol, accompanied by ferocious armoured dogs that had been trained to kill and disembowel, they preyed on the local communities, already plague-enfeebled, forcing them to supply food and women and slaves, and whatever else the soldiers might desire.’

The diseases the Spaniards carried (the precise identities of which are still debated) spread with alarming speed through local communities, killing inhabitants in numbers that, according to one writer at the time, ‘could not be counted’. Stannard believes that, by the end of the sixteenth century, the Spanish had been directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of between 60 and 80 million indigenous people in the Caribbean, Mexico and Central America. Even if one were to discount the millions of deaths resulting from diseases, this would still make the Spanish conquest of the New World the greatest act of genocide in recorded history.

In the end, regardless of the true occurrence of cannibalism, it was tall tales, especially those with a bestial or man-eating angle, that effectively dehumanised the islanders. Not only did this serve to justify Spain’s rapidly evolving slave-raiding agenda, it also established an attitude towards the locals that came to resemble pest control. Leaving behind neither pyramids nor stone glyphs, the indigenous cultures of the Caribbean have all but disappeared.

Footnote

1 In Northern Australia, East Africa, and the Indian Ocean, some cultures do employ a family of sucker-backed fish called remoras (Echeneidae) to hunt for sea turtles. Remoras are renowned for attaching themselves to larger fish as well as to turtles. The original behaviour is a form of commensalism – a relationship in which one species (the remora) obtains a benefit (in this case protection and food dropped by the host) while the other species gains nothing but isn’t harmed.