SIEGES, STRANDINGS AND STARVATION: SURVIVAL CANNIBALISM

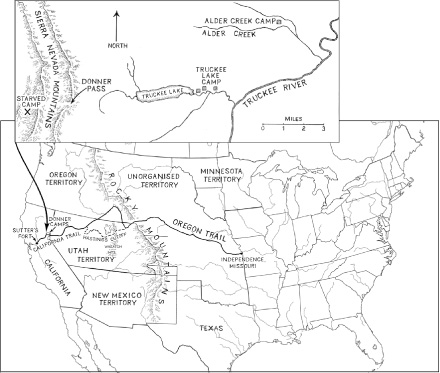

It is a long road and those who follow it must meet certain risks; exhaustion and disease, alkali water, and Indian arrows will take a toll. But the greatest problem is a simple one, and the chief opponent is Time. If August sees them on the Humboldt and September at the Sierra – good! Even if they are a month delayed, all may yet go well. But let it come late October, or November, and the snow-storms block the heights, when wagons are light of provisions and the oxen lean, then will come a story.

George R. Stewart, Ordeal by Hunger

IT WAS LATE JUNE and by the time we arrived at Alder Creek, the air at snout level (which was currently about an inch off the ground) had risen to an uncomfortable 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Kayle, a five-year-old black-and-white border collie, raised her head, searching in vain for a breeze. There was a rustling in the brush nearby and something (probably a chipmunk) provided a welcome distraction to the task at hand. Kayle took a step toward the commotion.

Kayle was in training as an HHRD dog, an abbreviation for Historical Human Remains Detection. In short, Kayle was searching for bodies – old ones.

I hitched my backpack higher and followed, taking a moment to survey the meadow where Kayle slowly sniffed her way in the direction of a large pine tree. At an elevation of 5,800 feet, we were in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, just across the Nevada border and into California. It had been a dry spring throughout the American West and the fist-sized clumps of grass that had sprouted from the rocky soil were already turning brown. We’d passed several creek beds and I remembered reading about the muddy conditions that had led to the construction of a low boardwalk for the tourists visiting the incongruously named Donner Camp and Picnic Area.

No need for a boardwalk today, I thought.

We headed further and further away from the trail and into a mountain meadow strewn with wildflowers: orange coloured Indian paintbrush, yellow cinquefoils, purple penstemon. I’d come to the Alder Creek historic site to learn about the Donner Party: probably the most infamous example of cannibalism in US history.

In the summer of 1846 eighty-seven pioneers, many of them children accompanying their parents, set out from Independence, Missouri, for the California coast, eventually taking perhaps the most ill-advised shortcut in the history of human travel. Dreamed up by Lansford Hastings, a promoter who had never taken the route himself, the Hastings Cutoff turned out to be 125 miles longer than the established route to the west coast. It was also a far more treacherous trek, forcing the travellers to blaze a trail through the Wasatch Mountains before sending them on a forty-mile hike across Utah’s Great Salt Desert. Tempers flared as wagons broke down and livestock were lost, stolen, or died from exhaustion. People also died, some from natural causes such as tuberculosis, while others were shot or stabbed. As the heat of summer transitioned into the dread of fall, the travellers found themselves in a desperate race to cross the Sierra Nevada before winter conditions turned the high mountain passes into impenetrable barriers. Along the way, sixty-year-old businessman George Donner had been elected leader of the group, though he had no trail experience.

On 26 September 1846 the wagon train finally rejoined the traditional westward route. Hastings’s shortcut had delayed the Donner Party an entire month with potentially catastrophic consequences. Disheartened, the pioneers followed the well-worn Emigrants’ Trail along the Humboldt river, which by that time of year had been reduced to a series of stagnant pools. As they made their way along the Humboldt, raids by Paiute Indians further depleted their weary and emaciated livestock.

By October, any ideas of maintaining the wagon train as a cohesive unit had been abandoned. Instead, bickering, stress, exhaustion and desperation split the group along class, ethnic and family lines. Those who could not keep up fell further and further behind. Afraid to overburden their oxen or slow down his own family’s progress, pioneer Louis Keseberg had informed one of the older men, a Mr Hardcoop (none of the survivors could remember his first name), that he would have to walk. Hardcoop was having an increasingly difficult time with his forced march and eventually he was left behind on the trail. Another elderly bachelor was murdered by two of the teamsters (men tasked with driving the draught animals) accompanying the group.

By the end of October it still appeared that most of the Donner Party had overcome terrible advice, challenging terrain, short rations, injuries and death. With the group now split in two and separated by a distance of nearly ten miles, those accompanying the lead wagons stood before the final mountain pass, three miles from the summit and a mere fifty miles from civilisation. They decided to rest until the following day. But on the night before they were to make their final push, and weeks before the first winter storms usually arrived, disaster struck.

On the morning of 1 November, the fifty-nine members of the Donner Party in the lead group awoke to discover that five-foot snowdrifts had obliterated the trail ahead, transforming what promised to be a final dash through a breach in the mountains into an impossible task. It soon became apparent that there would be no crossing over the Sierras until the following spring. So the dejected pioneers were forced to turn back, leaving behind the boulder-strewn gap that would become known as the Donner Pass.

A DAY BEFORE OUR TREK across Alder Creek meadow, I had stood with Kristin Johnson and two of her colleagues, John Grebenkemper and Ken Dunn, at the very same spot where the long, cross-country journey of the Donner Party had come to a halt. Looking down from the mountain, I was suddenly impressed by how resourceful and tough the pioneers had been to have made it even this far.

Johnson, an enthusiastic historian and researcher, was living proof that many of the mysteries surrounding the Donner Party remained unsolved, including the one we would be working on at Alder Creek. It was a mystery that involved the leader of the Donner Party and the very person for whom the group had been named.

On 1 November 1846 the pace-setting travellers whose journey had been halted at the mountain pass decided to backtrack several miles to Truckee Lake (now Donner Lake), where they had passed an abandoned cabin that the members of a previous wagon train had constructed two years earlier. Now they would overwinter there. The pioneers quickly built two more cabins and crowded in as best they could.

With the benefit of hindsight, questions have arisen as to why the Donner Party did not simply backtrack another thirty miles, which would have enabled them to overwinter out of the Sierras altogether. A possible explanation was their utter lack of knowledge about exactly where they had chosen to camp. Unlike other wagon trains, they had hired no seasoned mountain-men to guide them.

The twenty-one members of the Donner Party who had lagged behind never even made it to Truckee Lake. Nor did they experience the crushing disappointment of the final mountain pass. A broken wagon axle had halted the group, which included George Donner, his brother Jacob, their families and several teamsters. They eventually made it to the Alder Creek valley, two miles west of the Emigrant Trail and eight miles from the Truckee Lake cabin, when the winter storm caught them completely in the open. According to survivor Virginia Reed, they ‘hastily put up brush sheds, covering them with pine boughs’. Although the intention seems to have been to use Alder Creek as a quick rest-stop before a final push into California, the weather and their weakened conditions dictated that, like those stranded at Truckee Lake, there would be no further travel until the spring thaw.

By now, George Donner had been incapacitated by what began as a superficial wound to his hand received while repairing his wagon. As the days and weeks passed, the infection crept up his arm and he would spend the last four months of his life trapped in a draughty shelter built beneath a large pine. Here, the head of the Donner Party would become a helpless observer of the horrors that would soon overtake his family and those who worked for him.

Now the entire party, separated by eight miles and trapped in hurriedly constructed shacks, faced a winter of starvation and madness.

THE DAY AFTER STANDING ATOP Donner Pass, Kristin, John, Ken and I visited Alder Creek, hiking away from the well-worn trails. Kayle led us around an L-shaped stand of ponderosa pines and into a meadow covered with white flowers.

I watched the dog, as, with her nose to the ground, the border collie made several passes over a bare-looking patch of earth, halting abruptly several times, only to double back over the same spot. Then she stopped, sat and quickly pointed her nose downward. As my companions and I watched, Kayle stood up, moved about a yard further and repeated the same motion.

John turned to me and explained that these were alerts. I had learned previously that when an HHRD dog detects the scent of decomposed human remains it responds with a trained action like this.

On 16 December 1846 a party of seventeen men, women and children stranded at the Truckee Lake camp fashioned snowshoes and attempted a break-out. Early on, two of them who had started the trip without the makeshift footwear decided to turn back. The group of fifteen, which also included a pair of Miwok Indians who had joined the company in Nevada, would become known as the Forlorn Hope, and they would be making their attempt through the heart of a storm-blasted winter in the country’s snowiest region.1 According to Kristin Johnson, sometime around 12 January the survivors stumbled into a small encampment of local Indians who gave them what food they could spare (mostly seeds and acorn bread).2 They guided the wraith-like figures partway down the mountain but they did so warily. The pitiful travellers were not only frozen, but some of them had also begun to lose their grip on reality.

On 17 January 1847 Forlorn Hope member William Eddy reached the Johnson Ranch, located at the edge of a small farming community in the Sacramento valley. By the time he staggered up to one of the cabins, Eddy looked more like a skeleton than a man. The skin of his face was drawn tightly over his skull and his eyes were sunken deeply into their sockets. His appearance sent the cabin owner’s daughter away from her own front door shrieking in terror. Several horrified locals reportedly retraced William Eddy’s bloody footprints into the forest and discovered six more survivors – a man and five women. The Forlorn Hope had departed the Truckee Lake camp thirty-three days earlier with barely a week’s worth of short rations. Eight of them eventually perished – all males – and, according to Kristin Johnson, ‘there’s no question’ that seven of the dead were cannibalised.

Nearly 160 years later, science writer Sharman Apt Russell wrote about the results of a 1944–45 Minnesota University study on the effects of semi-starvation.

Prolonged hunger carves the body into what researchers call the asthenic build [i.e. debilitated, lacking strength or vigour]. The face grows thin, with pronounced cheekbones, Atrophied facial muscles account for the ‘mask of famine’, a seemingly unemotional, apathetic stare … the clavicle looks sharp as a blade … Ribs are prominent. The scapula(e) … move like wings. The vertebral column is a line of knobs … the legs like sticks.

Had modern physicians been present to monitor the surviving members of the Forlorn Hope, in all likelihood these unfortunates would have exhibited most of the physiological signs of starvation: low resting metabolic rates (the amount of energy expended at rest each day), slow, shallow breathing and lower body temperatures (which would have been present even without the frigid conditions).3 Another bodily response to starvation is low blood pressure, a condition that can lead to fainting, especially upon standing up. Like the lethargic movements that characterise starving people, these physiological changes are the body’s involuntary attempts at conserving energy.

Changes in the starved body occur at the biochemical level as well, and in the case of the Donner Party, their hunger-racked bodies would have begun to consume themselves. At first, carbohydrates stored in the liver and muscles would have been broken down into energy-rich sugars. Fat would have been metabolised next. Depending on the individual, these fat stores could have lasted weeks or even months. Finally, proteins, the primary structural components of muscles and organs, would have been broken down into their chemical components: amino acids. In effect, during the latter stages of starvation, the body’s system of metabolic checks and balances hijacks the energy it requires, obtaining it from the chemical bond energy that had previously been used to hold together complex protein molecules. This protein breakdown (in places like the skin, bones and skeletal muscles) produces the wasted-away appearance that characterises starvation victims.

Besides physiological and behavioural effects of starvation, researchers have identified changes that occur in groups experiencing food shortages or famines. In 1980 anthropologist Robert Dirks wrote that social groups facing starvation go through three distinct phases. During the first, the activity of the group increases, as do ‘positive reciprocities’. This can be thought of as an initial alarm response during which group members become more gregarious as they confront and attempt to solve the problem. Although emotions may run high, communal activity increases for a short time. The second phase occurs as the physiological effects of starvation begin to exhibit themselves. During this time, energy is conserved and the group becomes partitioned, usually along family lines. Non-relatives and even friends are often excluded. Acts of altruism decline in frequency with a concurrent increase in stealing, aggression and random acts of violence.

The third or terminal phase of starvation is often characterised by a complete collapse of anything resembling social order. Efforts at cooperation also fall off, even within families. The rate of physical activity also decreases to near zero as the exhausted and starving individuals remain motionless for hours, basically doing nothing. Some victims of starvation do not fall into these broad patterns. These individuals are capable of heroic gestures. They are also capable of murder and cannibalism – and sometimes both.

In The Cannibal Within, Lewis Petrinovich argues that this type of cannibalism is an evolved human trait that functions to optimise the chances of survival (and thus, reproductive success). ‘It is not advantageous to be a member of another species, of a different race, or even to be a stranger when people are driven by starvation. The best thing to be is a member of a family group, and not be too young or too old.’

ONLY THREE YEARS BEFORE the Minnesota University study, which came to be called the Minnesota Experiment, starvation was taking place on a massive scale in a major European city. For the inhabitants of Leningrad, the horror was far beyond the limits of a supervised research project.

Today known as St Petersburg, Leningrad was a major industrial city and the birthplace of the Russian Revolution. In June 1941 Adolf Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa – a massive, three-pronged assault against the Soviet Union. By September, the nearly three million Leningraders were completely surrounded by German and Finnish forces. With little advance preparation by the local authorities, food shortages and dwindling fuel supplies had become grave concerns. The city’s zoo animals were killed and consumed, and soon after people began butchering and eating their pets. Most of the city’s food reserves were housed in a series of closely spaced wooden structures that were destroyed after a single bombing raid by the Luftwaffe.

On 29 September 1941 Hitler wrote, ‘All offers of surrender from Leningrad must be rejected. In this struggle for survival, we have no interest in keeping even a proportion of the city’s population alive’. German commanders were forbidden from accepting any type of surrender from the city’s inhabitants. ‘Leningrad must die of starvation,’ Hitler declared.

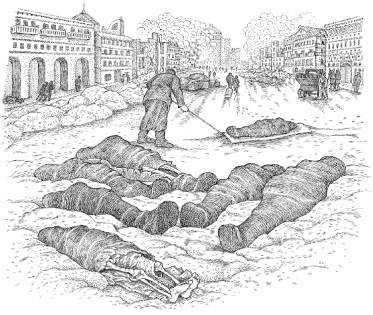

With essential supplies all but cut off, living conditions within the embattled city plummeted along with the temperatures, which routinely reached minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit, in what became a winter of record-breaking cold. Although daily artillery and aerial bombardments claimed citizens at random, far more Leningraders died of exposure, sickness and especially starvation. As a result, by December 1941 the unburied dead were accumulating by the tens of thousands.

As conditions worsened, social order began to unravel and violent criminals took to the streets. Leningrad’s citizens were robbed or murdered for the food they carried home from the market or for the ration cards that allotted them as little as seventy-five grams of bread per day.4

According to historian David Glantz, 50,000 Leningraders starved to death in December 1941 and 120,000 died in January 1942. Archivist Nadezhda Cherepenina reported that, during the month of February 1942, ‘the registry offices recorded 108,029 deaths (roughly 5 per cent of the total population) – the highest figure in the entire siege’.5

Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times correspondent Harrison Salisbury wrote that once the harsh winter took hold, most of Leningrad’s population was reduced to eating bark, carpenter’s glue and the leather belt drives found in motors. But there were exceptions. ‘These were the cannibals and their allies – fat, oily, steely eyed, calculating, the most terrible men and women of their day.’

As rumours of cannibalism swept the city, so too did reports of kidnappings. It was said that children were being seized off the streets ‘because their flesh was so much more tender’. Women were apparently a popular second choice because of the extra fat they carried.

‘In the worst period of the siege,’ a survivor noted, ‘Leningrad was in the power of the cannibals.’

Just as ominous, perhaps, was the sudden availability of suspicious-looking meat in Leningrad’s central market. The traders were new as well, selling their grisly wares (which they claimed to be horse, dog or cat flesh) to those shoppers with enough money to buy them. According to numerous survivor accounts, meat patties made from ground-up human flesh were being sold as early as November 1941.

Also detailed were the gruesome finds made by those assigned to deal with the thousands of dead bodies that were stacking up at the city’s largest cemeteries and elsewhere. After dynamiting the frozen ground, ‘[the men] noticed as they piled the corpses into mass graves that pieces were missing, usually the fat thighs or arms or shoulders’. The bodies of women with their breasts or buttocks cut off were found, as were severed legs with the meat cut away. In other instances, only the heads of the deceased were found. People were arrested for possessing body parts or the corpses of unrelated children.

But beyond the diaries and the accounts of Leningraders who lived through the siege, what other evidence for cannibalism has been uncovered? No physical evidence survives, no bones with cut marks suggestive of butchering or signs that they had been cooked.

As for the official line, a deliberate effort was made to eliminate any reference to this. ‘You will look in vain in the published official histories for reports of the trade in human flesh,’ Salisbury wrote in 1969, and this remained so until relatively recently. All mention of cannibalism had been purged from the public record – Stalin and other Communist Party leaders wanted to portray Leningrad’s besieged citizens as heroes. Leningrad was the first of twelve Russian cities to be awarded the honorary title ‘Hero City’ for the resilience of its citizens during World War II. Rumours of cannibalism would have cast Leningraders in a far less glorious light.

In 2004 the official reports made immediately after the war by the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) were released.6 They revealed that approximately 2,000 Leningraders had been arrested for cannibalism during the siege (many of them executed on the spot). In most instances these were normal people driven by impossible conditions to commit unspeakable acts. Cut off from food and fuel and surrounded by the bodies of the dead, preserved by the arctic temperatures, Leningrad’s starving citizens faced the same difficult decisions encountered by other disaster survivors: should they consume the dead or die themselves? According to an array of independent accounts as well as those from the NKVD, many of them chose to live.

Back to the Sierra Nevada, where, on 26 December 1846, only ten days after leaving the Truckee Lake camp, the members of the Forlorn Hope were lost deep in the frozen mountains. Only a third of the way into their nightmarish trek, they reportedly decided that without resorting to cannibalism they would all die. At first the hikers discussed eating the bodies of anyone who died but soon they began to debate more desperate measures: drawing straws with the loser sacrificed so that the others might survive.

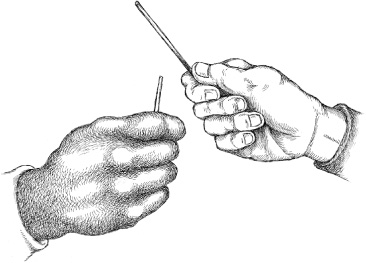

The procedure was known to seafarers as ‘the custom of the sea’, a measure that provided (at least in theory) some rules for officers and their men should they find themselves cast adrift on the open ocean. Sailors drew straws, with the short-straw holder giving up his life so that the rest might eat. In some descriptions, the person drawing the next-shortest straw would act as the executioner. Although heroic in concept and theoretically fair in design, modified versions of ‘the custom of the sea’ were sometimes lacking in either quality.

In perhaps the most famous case, in 1765, a storm demasted the American sloop Peggy, leaving her adrift in the Atlantic Ocean. On board were the captain, his crew of nine and an African slave. They had been en route to New York from the Azores with a hold full of wine and brandy. After a month, they had nothing to eat but plenty to drink, a fact driven home when the spooked captain of a potential rescue vessel took one look at the Peggy’s raggedy-looking crew of drunks and promptly sailed away. The Peggy’s captain, perhaps fearing for his own life, remained in his cabin, armed with a pistol.

Soon after their thwarted rescue, the Peggy’s first mate appeared below deck, informing his captain that the men had already eaten the ship’s cat, their uniform buttons, and a leather bilge pump. They had decided to draw lots, with the loser served up as dinner. The captain waved the mate away with a loaded pistol but the man returned moments later to report on the lottery results. By an incredible coincidence, the slave had drawn the short straw. Although the ‘poor Ethiopian’ begged for his life, the captain was unable to prevent the man’s murder, later writing that as they prepared to cook the body, one sailor rushed in, tore away the slave’s liver and ate it raw.

Three days later the line jumper was said to have gone insane and died. Then, in a demonstration that the crew of the Peggy had lost none of its well-honed survival skills, they tossed their mate’s body overboard, fearful of the harmful effects of consuming a crazy man. Soon another round of straw-drawing took place, but this time the most popular and competent sailor drew the stubby stick (in this case an inked slip of paper). After hearing his final request that he be killed quickly, the man’s drunken shipmates acted accordingly and gave him a twelve-hour reprieve, during which the doomed man reportedly went deaf and lost the remainder of his mind. Just in the nick of time, a rescue ship was spotted. This time, the crew feigned sobriety long enough to be rescued, though the reprieved man reportedly never recovered either his hearing or his sanity.

LOST IN THE SIERRA NEVADA with no food, the members of the Forlorn Hope had also decided to draw lots. Patrick Dolan, a thirty-five-year-old bachelor from Dublin, was the loser. At this point, no one had the heart, or possibly the strength, to carry out the killing. Someone suggested that two of the men fight it out with pistols ‘until one or both was slain’, but this proposal was also rejected. Two days later, and before they could reconsider their options, a snowstorm rendered such choices unnecessary. Three of the group members, including Patrick Dolan, died during the night.

The next morning, after one of the survivors was able to light a fire, according to historian Jesse Quinn Thornton, ‘his miserable companions cut the flesh from the arms and legs of Patrick Dolan, and roasted and ate it, averting their faces from each other and weeping’. Parts of the other corpses were eaten over the next few days, but it wasn’t long before the survivors ran out of food again.

By now the party was exhibiting another symptom of starvation: they were bickering among themselves. A thirty-year-old carpenter, William Foster, reportedly suggested that they kill and eat three of the women (presumably not his own wife), but when this idea failed to take hold he proposed that they the shoot their Indian companions, Luis and Salvador, instead. The two men registered their votes by slipping away from the camp. Foster and the others eventually came upon them somewhere along the trail and there are several versions of what happened next.

In most accounts, Foster murdered the men, about whom little is known except that they had risked their lives on multiple occasions to save the stranded pioneers. In another version of the story, Salvador was already dead when the hikers discovered them and Luis died an hour later. However these men died, there is agreement on what happened next. According to John Sinclair, the alcalde (municipal magistrate) of Sacramento, who later presided over hearings related to the tragedy, ‘Being nearly out of provisions, and knowing not how far they might be from the settlements, they took their flesh likewise.’ Foster, who survived the whole ordeal, was never prosecuted, nor did he garner much blame for the incident. Most descriptions of the murders portray Foster’s actions as being those of a decent man deranged by starvation.

Back in the mountain camps, more people were dying, and by the midpoint of the Forlorn Hope’s dreadful trek, four men at the Alder Creek campsite, including George Donner’s younger brother Jacob, had perished.

Beginning in early 1847, four rescue or relief parties trekked into and out of the Sierras in fairly rapid succession. They met with varying degrees of success, tempered by cowardice, greed and inhumanity. The weather caused mayhem along the trail, sometimes proving fatal. During the ill-fated Second Relief, a blizzard forced rescuers to abandon two families of Donner Party survivors at what became known as ‘starved camp’.7 Alone on a mountain trail they thought would lead them to safety, the thirteen starved pioneers huddled in a frozen snow pit for eleven days. Three of them died and the survivors were forced to eat their own dead relatives, including children. They were eventually discovered by members of Third Relief, several of whom led them out of the Sierras and to safety.

One month earlier, in mid-February, First Relief, minus several men who had given up, crossed the high mountain pass where the Donner Party had been halted in November. They set up camp for the night, building their fire on a platform of logs that sat atop snow they estimated to be around thirty feet deep. The following day, seven men descended the eastern slope of the Sierras and set out across the icy expanse of Truckee Lake, arriving at the spot where the survivors of the Forlorn Hope had told them the cabins were located. First Relief member Daniel Rhoads told historian H. H. Bancroft what happened next.

We looked all around but no living thing except ourselves was in sight and we thought that all must have perished. We raised a loud halloo and then we saw a woman emerge from a hole in the snow. As we approached her several others made their appearance in like manner, coming out of the snow. They were gaunt with famine and I never can forget the horrible, ghastly sight they presented. The first woman spoke in a hollow voice very much agitated and said, ‘Are you men from California or do you come from heaven?’

The First Relief rescuers were shocked by the condition of the survivors. Many of the skeletal figures could barely move as they spoke in raspy whispers, begging for bread. Some appeared to have gone mad. Others were unconscious as they lay on beds made of pine boughs. The stunned Californians handed out small portions of food to each of the survivors – biscuits and beef mostly – but that night a guard was posted to ensure that their provisions would remain safe from the starving pioneers.

Outside the cabin, the members of the rescue party saw smashed animal bones and tattered pieces of hide littering the area. Then there were the human bodies, twelve of them, scattered about the campsite, some covered by quilts, others with limbs jutting out of the snow. There were no signs of cannibalism.

The next day the weather broke clear, and three of the First Relievers headed for the Alder Creek camp. In a pair of tent-like shelters they found Tamzene Donner, George’s wife, her newly widowed sister-in-law Elizabeth (who could barely walk), the twelve Donner children and several others, including George Donner. Feverish and infirm, his wounded hand had become a slow death sentence.

Taking stock of the situation, Reason Tucker, co-leader of First Relief, knew that they needed to get out of the Sierras before another storm trapped them all there. Tucker’s other realisation was a difficult one, for he knew it would be physically impossible for many of the starving pioneers to hike out with them. Some were too young, others too far gone, and although he and his men had cached provisions along the trail, there would not be enough food for the entire group.

Sickly Elizabeth Donner decided that four of her children would never make it through the deep snow and so they would remain with her at Alder Creek. Tamzene, on the other hand, was healthy enough to travel and she was urged to depart with her five daughters. She refused, insisting that she would never leave George alone to die. She decided to keep her three youngest children with her, presumably waiting for the next relief party, whose arrival they apparently believed to be imminent.

On 22 February six members of the Alder Creek camp hiked out with First Relief accompanied by seventeen others from Truckee Lake. That left thirty-one members of the Donner Party still trapped and starving.

A long week later, members of Second Relief arrived at the mountain camps, but by then conditions at both sites had taken a dramatic downturn. In late 1847 reporter J. H. Merryman published the following account, obtaining his information from a letter penned by Donner Party member James Reed. Exiled earlier in the journey for stabbing a man to death in a fight, Reed had ridden on to California. Now he had returned, leading Second Relief:

[Reed’s] party immediately commenced distributing their provisions among the sufferers, all of whom they found in the most deplorable condition. Among the cabins lay the fleshless bones and half eaten bodies of the victims of famine. There lay the limbs, the skulls, and the hair of the poor beings, who had died from want, and whose flesh had preserved the lives of their surviving comrades, who, shivering in their filthy rags, and surrounded by the remains of their unholy feast looked more like demons than human beings …

And in 1849, J. Q. Thornton (who also interviewed James Reed in late 1847) wrote the following about Reed’s entry into one of the Truckee Lake cabins:

The mutilated body of a friend, having nearly all the flesh torn away, was seen at the door – the head and face remaining entire. Half consumed limbs were seen concealed in trunks. Bones were scattered about. Human hair of different colors was seen in tuffs [sic] about the fire-place.

Reed soon headed toward the Alder Creek camp, where Thornton’s account continues:

They had consumed four bodies, and the children were sitting upon a log, with their faces stained with blood, devouring the half-roasted liver and heart of the father [Jacob Donner], unconscious of the approach of the men, of whom they took not the slightest notice even after they came up. Mrs. Jacob Donner was in a helpless condition, without anything whatever to eat except the body of her husband, and she declared that she would die before she would eat of this. Around the fire were hair, bones, skulls, and the fragments of half-consumed limbs.

Second Relief departed the camps on 1 March, but their blizzard-interrupted trek out of the mountains would become yet another misadventure.

When the small party of men that made up Third Relief arrived at the mountain camps nearly two weeks later, they found further scenes of horror at the cabins and more dead bodies at Alder Creek. With the last of her surviving children finally accompanying the rescuers, Tamzene Donner turned down one final opportunity to save herself, deciding instead to return to the side of her frail husband. When George Donner died in late March, she wrapped his body in a sheet, said her last goodbyes and headed back to the Truckee Lake camp. It would be Tamzene’s final journey.

Donner Party member Louis Keseberg, who had not come down from the mountain because of a debilitating wound to his foot, later testified that Mrs Donner had stumbled, half frozen, into his cabin one night. She had apparently fallen into a creek. Keseberg said that he wrapped her in blankets but found her dead the next morning. Sometime after the Fourth Relief (in reality a salvage team) showed up on 17 April, their leader, William Fallon, wrote in his diary, ‘No traces of her person could be found.’ There was no real mystery, though, since by his own admission Keseberg, whom they had found alive, had eaten Mrs Donner as well as many of those who had died in the mountain camps. In fact he had been eating nothing but human bodies for two months.

On 21 April 1847 Fourth Relief, accompanied by Louis Keseberg, left the Truckee Lake camp and four days later they reached Sutter’s Fort (now Sacramento). The last living member of the Donner Party had come down from the mountains.

That summer, General Stephen Kearny and his men were returning east after a brief war with Mexico. They stopped at the abandoned Truckee Lake camp, finding ‘human skeletons … in every variety of mutilation. A more revolting and appalling spectacle I never witnessed’, wrote one of Kearny’s men.

The general ordered the men in his entourage to bury the dead, but instead they reportedly deposited the mostly mummified body parts in the centre of a cabin before torching it. At Alder Creek, Kearny and his men found the intact and sheet-wrapped body of George Donner. There is no consensus about whether they buried him or not.

ALTHOUGH THE TALE of the Donner Party has become one of the darkest chapters in the history of the American West, time has also transformed it into something else. The dead pioneers who stare at us blankly from cracked daguerreo-types are too often a source of amusement (‘Donner Party, your table is ready’) and the butt of macabre jokes. To a public that has, for the most part, become anaesthetised to the concepts of gore and gruesome death, the Donner Party is no longer the stuff of nightmares. Instead, any thoughts we might have about these pioneers usually relate to vague notions about cannibalism or perhaps the perils of taking ill-advised shortcuts.

In the spring of 2010 all that changed. The long-dead travellers were back in the news, and this time the story behind the renewed media interest was neither funny nor lurid. It was actually quite remarkable. During the previous decade, an archaeological team from the University of Montana and Appalachian State University unearthed the remains of a campsite at Alder Creek that would become known as the Meadow Hearth. It contained artefacts like cooking utensils, fragments of pottery and percussion caps – small, explosive-filled cylinders of copper or brass that allowed muzzleloaders to fire in any weather. Each of these items dated to the 1840s. There were also thousands of bone fragments and, given the Donner Party’s reputation, interest soon centred on whether or not any of these bones were human in origin.

Six years later, the researchers had completed their analysis of the artefacts and were preparing a scientific paper that would detail their findings. Now, though, and before their paper could be published, a spate of articles and news blurbs announced that the scientists had uncovered physical evidence that led them seriously to question the very act for which the Donners had attained their infamy.

‘Analysis finally clears Donner Party of rumored cannibalism’, read one media report. Even The New York Times got into the act. ‘No cannibalism among the Donner Party?’ read the bet-hedging headline in a Times-associated blog. My personal favourite was a headline from a blog post at The Rat: ‘Science crashes Donner Party.’

So was there any truth to the story of the Donner Party cannibalism?

Initially, the archaeological team working at the Meadow Hearth dig uncovered a thin layer of ash that they eventually determined to be the remains of an 1840sera campsite. Their efforts also revealed concentrations of charred wood and deposits of burned and calcined bone fragments. The latter occur when bone is subjected to high temperatures resulting in the loss of organic material, like the protein collagen. What’s left is a mineralised version of the original bone, and importantly, one that is more resistant to decomposition than it was in its original form. Calcined bone also provides anthropologists with strong evidence that the bones in question were cooked.

All told, the university researchers collected a total of 16,204 bone fragments from the Meadow Hearth excavation, a number that makes it far easier to understand why it took them six years to analyse their data. Unfortunately, not everyone was as patient as the scientists had been, and in 2010, an overeager public relations department at Appalachian State University rushed out a press release claiming: ‘The legend of the Donner Party was primarily created by print journalists, who embellished the tales based on their own Victorian macabre sensibilities and their desire to sell more newspapers.’

They went on to add: ‘The survivors fiercely denied allegations of cannibalism,’ a statement contradicted by Donner Party survivors, rescuers and historians alike. Finally, and as if to further convince the world that Donner Party members were actually humans and not crazed cannibals, the ASU PR crew announced that pieces of writing slate and broken china found near the cooking hearth ‘suggest an attempt to maintain a sense of a “normal life”, a family intent on maintaining a routine of lessons, to preserve the dignified manners from another time and place, a refusal to accept the harsh reality of the moment, and a hope that the future was coming’.

The response was a predictable media storm. But in reality, the idea that the Meadow Hearth dig’s findings proved that there was no cannibalism among the Donner Party was based on a misunderstanding of one of their findings. The PR release had claimed that the discovery of human bones among the varied calcined animal bones found at the site would have been statistically probable ‘if humans were processed in the same way animals were processed’. And therein lies the problem, because as it turns out the Donner Party did not process human bones and animal bones in the same way. And here’s why.

Of the thousands of bone fragments from the Meadow Hearth examined by researchers, 362 of them showed evidence of human processing. About one quarter of those had abrasions and scratch marks, which indicate that the bones had been smashed into bits. Other pieces of bone exhibited a condition known as ‘pot polish’, a smoothing of the edges that results from the bones being stirred in a pot. To anthropologists this was another strong indicator that the bone fragments had been cooked.

As starvation set in, the stranded members of the Donner Party ate whatever they could find. According to historical accounts, they consumed rodents, leather belts and laces, tree bark and a gooey pulp scraped from boiled animal hides. By the end of January 1847 they began consuming their pet dogs. The analysis by Gwen Robbins and her co-workers indicated that bones from several types of mammals had been smashed, boiled and burned by someone at the Alder Creek camp. This would have been done in an effort to render the bones edible, while extracting every bit of nutrient possible. In all likelihood, these would have been the types of last-resort measures undertaken before the survivors resorted to cannibalism, which did not begin in the mountain camps until the last week of February 1847, sometime after the departure of First Relief on 22 February (and before the arrival of Second Relief a week later). The practice of consuming dead bodies continued until the survivors either died or were rescued, and for everyone except the soon-to-be christened Donner Party monster, Louis Keseberg, cannibalism would have lasted only a week or two at most, a vitally important point.

Given the large number of bodies present at the Truckee Lake and Alder Creek campsites, and the short amount of time during which cannibalism occurred, there would have been no need to process human bones in the same manner in which animal bones had been processed previously. Essentially, that’s because once cannibalism began at the camps there would have been ample human flesh for the ever-dwindling number of survivors to eat, more than enough to make cooking and recooking the human bones completely unnecessary.

Because uncooked bones would not have been preserved in the acidic soil of the conifer-dense Sierras, there would be no human bones for archaeologists to uncover. Therefore, the absence of calcined human bones from the Meadow Hearth proves only that human and animal bodies were not processed in the same way. The evidence does not place the practice of cannibalism by members of the Alder Creek camp into doubt, nor does it have any bearing whatsoever on the cannibalism that took place at the Truckee Lake camp, within the Forlorn Hope, or at the Second Relief’s ‘starved camp’.8

IN ADDITION TO GEORGE DONNER, thirty-four members of the Donner Party died in the winter camps or trying to escape them – mostly from starvation and/or exposure. In 1990, anthropologist Donald Grayson conducted a demographic assessment of the Donner Party deaths and came up with some interesting information.

To be expected was the fact that children between one and five years of age, and older people (above the age of forty-nine), experienced high mortality rates (62.5 per cent and 100 per cent, respectively), primarily because both groups are more susceptible to hypothermia.

More surprising was that 53.1 per cent of males (a total of twenty-five) perished while only 29.4 per cent of females died (ten). Additionally, not only did more of the Donner men die, they also died sooner. Fourteen men died in between December 1846 and the end of January 1847, while females didn’t begin dying until February.

Another intriguing detail is that all eleven Donner Party bachelors (over eighteen years of age) who became trapped in the Sierras died, while only four of the eight married men, travelling with their families, perished during the ordeal.

The explanation for all this is probably a combination of biology and behaviour. Biologically, nutritional researchers believe that three significant physiological differences between males and females come into play during starvation conditions: (1) females metabolise protein more slowly than males (i.e. they don’t burn up their nutrients as quickly); (2) female daily caloric requirements are less (i.e. they don’t need as much food); and (3) females have greater fat reserves than males, thus more stored energy that can be metabolised during starvation conditions. Also, much of this fat is subcutaneous, located just below the skin, where it functions as a layer of insulation, helping to maintain the body’s core temperature during conditions of extreme cold.

The behavioural component of the gender survival differential relates to the fact that the Donner Party men did most of the hard physical labour on the journey, and that ultimately translated to serious health problems once their diets became compromised. Grayson later suggested a scenario that triggered the decline in the previously healthy males:

[W]hen the Donner Party hacked a trail through the Wasatch range … it was the men, not the women who bore the brunt of the labor … There is no way to know exactly how much this grueling labor affected the strength of the Donner Party men, but they surely emerged from the Wasatch Range with their internal energy stores drained, stores they were unable to renew during the long and arduous trip across the Great Basin Desert that followed.

So what about the fact that married men out-survived bachelors by such a wide margin? The reason for this may have to do with differences in the mammalian physiological response to stress, related to blood levels of the hormone cortisol, a steroid hormone released by the adrenal gland. Cortisol is linked to stress and is part of the body’s ‘fight or flight’ response to real or imagined threats. While it can have positive short-term effects, increased plasma levels of cortisol can also lead to decreased cognitive ability, depression of the immune system and impairment of the body’s ability to heal.9 In a 2010 study, researchers at the University of Chicago looked at hormone levels in test groups composed of married and unmarried college students who were placed in anxiety-filled situations. The bachelors had higher levels of cortisol than did married men subjected to the same levels of stress. Thus the experimenters concluded that ‘single and unpaired individuals are more responsive to psychological stress than married individuals, a finding consistent with a growing body of evidence showing that marriage and social support can buffer against stress’.

If one adds these findings to the data from Robert Dirks’s study in which one phase of starvation was for groups to become partitioned along family lines, what results is a strong indication as to why all of the mountain-stranded bachelors perished while fully half of their married counterparts survived.

WE’VE ALREADY LEARNED that cannibalism occurs across the entire animal kingdom, albeit more frequently in some groups than others. When the behaviour does happen, it happens for reasons that make perfect sense from an evolutionary standpoint: reducing competition, as a component of sexual behaviour, or an aspect of parental care. Cannibalism in animals is also widely seen as a natural response to stresses like overcrowding and food shortages. The unfortunates involved in shipwrecks, strandings and sieges who have resorted to cannibalism were exhibiting biologically and behaviourally predictable responses to specific and unusual forms of stress. Extreme conditions provoke extreme responses.

Additionally, like the male spiders that give up their lives and bodies to their mates, ultimately increasing the survival potential of their offspring, so too did the bodies of Donner Party members like Jacob Donner serve similar functions for their families.

In cannibalism-related tragedies such as that which befell the Donner Party, survivors have been given something like a free pass for committing acts that would otherwise be considered unforgivable. But where did this taboo come from? Why is the very idea of human cannibalism so abhorrent that it has historically justified the torture, murder or enslavement of its alleged practitioners?

Footnotes

1 Alternatively known in the literature as the Snowshoe Group; I used the Forlorn Hope to avoid confusion.

2 The Nisenan (sometimes referred to as the Maidu) were the indigenous people of the Sierra Nevada foothills.

3 Fasting or starving people often exhibit increased sensitivity to cold.

4 In a system designed to maximise industrial output, Leningrad’s blue-collar workers received the greatest food allowance, followed by white-collar workers, and finally dependants (who received as little as the equivalent of a slice and a half of additive-adulterated bread per day). Rations were reduced a total of five times between September and November 1941.

5 Most estimates put the eventual civilian death toll at somewhere between 800,000 and 1.5 million.

6 The NKVD was the Soviet secret police under Stalin from 1934 to 1943.

7 ‘Starved camp’ is thought to have been in Summit Valley, California, just west of Donner Pass.

8 The tale of the Donner Party wasn’t the only cannibalism story to emerge from the American West. In February 1874, gold prospector Alfred (or Alferd) Packer led a party of five men into Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. When weather conditions deteriorated, preventing their return, he murdered and ate them. When the bodies were discovered the following spring, four of the five had been completely stripped of flesh. Although the skeletons showed evidence of butchery, each was relatively complete and the bones showed no signs of smashing or cooking. Similar to the cannibalism reported to have taken place at the Alder Creek camp, Packer had no need to process the skeletons further – in this case because he presumably had enough meat to survive until the spring. During Packer’s sentencing, the judge was rumoured to have made the following statement, ‘There were only seven Democrats in Hinsdale County, and you ate five of them, you depraved Republican son of a bitch!’

9 The short-term, positive effects of cortisol release include a burst of energy (through an increase in blood sugar levels) and a lower sensitivity to pain (by reducing inflammation).