CHINA: BEYOND THE WESTERN TABOO

I think there is nothing barbarous and savage in that nation, from what I have been told, except that each man calls barbarism whatever is not his own practice; for indeed it seems we have no other test of truth and reason than the example and pattern of the opinions and customs of the country we live in.

Michel de Montaigne, Of Cannibals

ONE WAY TO SUPPORT a hypothesis that the origin, spread and persistence of the Western cannibalism taboo can be traced along a line leading back to the ancient Greeks would be to find a culture with an extensive historical record that existed for millennia without the significant influences of Homer, Herodotus and the Western writers who followed them.

Among many of the cultures that definitely weren’t reading the Greek mythology (the Aztecs and Caribs come to mind), there is little if any proof as to their definitive stance on cannibalism. While there is a significant body of evidence regarding the Aztec practice of human sacrifice, which was clearly depicted in both carved inscriptions (glyphs) and bark-paper books known as codices, there is no such consensus among historians that the Aztecs ever practised cannibalism, especially on a large scale. And while a few Spaniards present in Mexico during the Aztec conquest provided written accounts of cannibalism, sceptics might question whether such sources are genuinely reliable witnesses. Since there is no conclusive evidence that the behaviour was practised by either the Aztecs or Caribs, we need to look elsewhere for a group not influenced by the Ancient Greeks.

So, are there are non-Western cultures where we can find a different, more accepting, attitude to cannibalism? Surprisingly, to find evidence of this you need go not to the Wari’ of Brazil or the Fore of New Guinea, but to China, whose leaders have maintained what is apparently the world’s longest unbroken historical record. How did the Chinese deal with cannibalism – historically and in modern times?

There is general agreement among recent scholars that China has a long history of cannibalism.1 The evidence comes from an array of Chinese classics and dynastic chronicles, as well as an impressive compendium of eyewitness accounts, the latter providing some unsparingly gruesome details about many of the most recent incidents.

In Cannibalism in China, historian Key Ray Chong specified two forms of cannibalism: survival cannibalism, which might occur during a siege or famine, and learned cannibalism, which the author described as, ‘an institutionalized practice of consuming certain, but not all, parts of the human body’. He describes learned cannibalism as being publicly and culturally sanctioned, making it synonymous with the term ‘cultural cannibalism’.

As we have already seen, survival cannibalism was not unique among the Chinese, but the practice is worth discussing for several reasons – not the least of which was the frequency with which it occurred in China, coupled with a succession of governments whose responses varied from turning a blind eye to something close to official sanction. Perhaps the saddest and most surprising case (and the one with the greatest death toll) actually occurred in the mid-twentieth century, when starvation and cannibalism were only two aspects of a national calamity of unprecedented scope.

Chong’s investigation provides three examples of siege-related cannibalism recorded in Chinese classical literature. The oldest instance took place during a war between the states of Ch’u and Sung in 594 bce and occurred in the Sung capital city. It was also notable because it was apparently the first time that starving Chinese began exchanging one another’s children, so that they could be consumed by non-relatives – a practice made permissible by an imperial edict in 205 bce. The other examples took place in 279 bce in the besieged cities of Ch’u and Chi-mo, and in 259 bce in the city of Chao. In the latter instance, soldiers defending a castle reportedly cannibalised servants and concubines, followed by children, women and men ‘of low status’.

In total, Chong’s exhaustive research efforts yielded 153 and 177 occurrences of cannibalism linked to war and natural disaster, respectively. With no statistical difference in the numbers reported from the Han Dynasty (206 bce–ce 220) to the Ch’ing Dynasty (1644–1912), incidences of cannibalism in which varying numbers of people were consumed seem to have been fairly consistent throughout China’s long history. But rather than the decrease in reports of cannibalism one might expect to find in modern times, the opposite turns out to be true. The greatest number of deaths by cannibalism in China came as a direct result of Mao Zedong’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ from 1958 to 1961.

This government programme produced the worst famine in recorded history – a continent-spanning disaster in which at least 30 million, mostly rural, Chinese died of starvation.

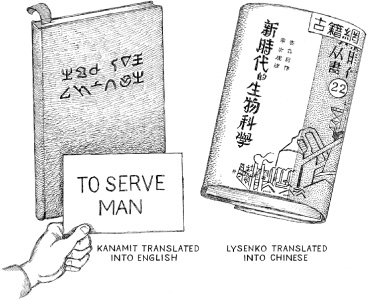

In an effort to transform China’s primarily agrarian economy into a modern communist society based on industrialisation and collectivisation, Mao Zedong, Chairman of the People’s Republic, ordered nearly three quarters of a billion farmers to move from private farms to massive agricultural collectives. More often than not, these communal farms were run by government officials who had no farming experience at all. To make matters worse, Mao had them institute an anti-scientific agricultural programme that had sprung from the brain of semi-literate Soviet peasant Trofim Lysenko in the late 1920s. Lysenkoism initially led to a deadly purge of Russian scientists and intellectuals. Eventually, it set the Soviet Union’s agricultural system back at least fifty years and resulted in millions of deaths by starvation.

Lysenko rejected the idea of selective breeding techniques, especially those based on Mendelian genetics. Instead he proposed his own muddled version of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s early-nineteenth-century theory that environmental factors produce needs or desires within an organism that lead to new adaptations. Lamarck’s infamous giraffes, their necks stretching and lengthening in an effort to reach leaves in an ever-higher tree canopy, remain a common misconception of how variation in traits like colour or size could be generated in any given population. Lamarck, trained as a naturalist, believed that the giraffes willed these changes to occur – changes that would then be passed on to future generations.

In Lysenko’s interpretation, the organisms exhibiting these needs and desires were crop plants like corn, wheat and vegetables. In that regard, he boasted that he could grow citrus trees in Siberia by cold-storing the seeds the previous year. These sorts of preposterous claims went on for decades, with those who questioned Lysenko’s ideas either eliminated or afraid to make their voices heard.

Not to be outdone by the Russians, Mao decided to install an ‘improved’ version of Lysenko’s agricultural programme in China. Instead of planting seeds apart from each other, for example, Mao instructed that they be ‘close planted’, since rather than competing for resources like water and nutrients, the tightly packed plants would, like the farmers Mao had packed into enormous communal farms, help each other to grow. The seedlings invariably died, although farmers were coerced into pretending that mature plants were so densely compacted that children could stand on them. Photographs depicting this ‘miracle’ were achieved by having the kids stand on a bench, hidden from view. Another of Mao’s brainstorms led to war being declared on sparrows, with the subsequent success of farmers’ efforts reflected by a concurrent increase in crop-munching insect populations.

Those who wrote about the catastrophe often did so at their own peril, but what they uncovered was truly shocking. For example, in Mubei (Tombstone), Yang Jisheng wrote that famine-starved ‘people ate tree bark, weeds, bird droppings, and flesh that had been cut from dead bodies, sometimes of their own family members’. The author, who lost his father to starvation, also believes that 36 million deaths is a more accurate number, although some estimates run as high as 46 million.

Combined with forced collectivisation and a purge of expertise, the Great Leap Forward ended in catastrophe. Agricultural output (mostly grain) fell significantly, even though local officials grossly inflated their actual production numbers to curry favour with Mao. This imaginary surplus led to increases in government quotas, so that most of what was produced was immediately confiscated by the state and even exported. Meanwhile, the farmers and rural populations starved. Farm animals were eaten, then pets and finally the bodies of the dead, especially children. Foreign correspondent Jasper Becker, former bureau chief of the South China Morning Post, wrote: ‘Travelling around the region over thirty years later, every peasant that I met aged over fifty said he personally knew of a case of cannibalism in his production team … Women would usually go out at night and cut flesh off the bodies, which lay under a thin layer of soil, and this would then be eaten in secrecy.’

Critics of Mao’s system were imprisoned or murdered and thousands of farmers were accused of hoarding grain and tortured to death. Fortunately, the Great Leap Forward, which was conceived as a five-year plan, was abandoned three years in. But although Chinese rulers looked the other way as starving populations consumed their dead, the cannibalism that took place was more of a necessity than a choice. These instances of survival cannibalism do not, therefore, definitively prove the absence of a cultural taboo against cannibalism in China.

Yet, under the banner of learned cannibalism, the Chinese appear to exhibit attitudes that differ significantly from those held in the West. For a start, Key Ray Chong provides a list of circumstances that might lead to an act of learned cannibalism. These were ‘hate, love, loyalty, filial piety, desire for human flesh as a delicacy, punishment, war, belief in the medical benefits of cannibalism, profit, insanity, coercion, religion, and superstition’. Some of these, it seems, are uniquely Chinese.

As anyone who has ever visited China (or to a lesser extent any big-city Chinatown) can attest, the Chinese consume a diverse range of creatures and their body parts. Many of these, like scorpions and chicken testicles, fall outside the range of typical Western diets – but does this have any bearing on the possible leap to eating human flesh? Perhaps, since as Maggie Kilgore pointed out in 1998, some items like rats, snakes, shellfish and creatures with paws are proscribed (at least in theory) by religions that follow Judaeo-Christian law, then maybe it should not come as such a surprise that the Chinese, with no such list of forbidden foods, had fewer qualms about consuming other humans.

Chong devoted an entire chapter of his book on cannibalism to ‘Methods of Cooking Human Flesh’ with the subheading ‘Baking, Roasting, Broiling, Smoke-drying, and Sun-drying’. And rather than an emergency ration consumed as a last resort, there are many reports of exotic human dishes prepared for royalty and upper-class citizens. T’ao Tsung-yi, a writer during the Yüan Dynasty (1271–1368), wrote that ‘children’s meat was the best food of all in taste’, followed by women and then men. In Shui Hu Chuan (Outlaws of the Marsh), a novel written in the twelfth century, there are numerous references to steamed dumplings stuffed with minced human flesh, as well as a rather nonchalant attitude among merchants and customers regarding the sale of human meat.

Even if epicurean cannibalism wasn’t limited to the Chinese, the extent to which it was set down in detail certainly was. Amidst information on ‘five regional cuisines’ (Szechwan, Canton, Fukien, Shantung and Honon), the San Kuo Yen Ki (Romance of the Three Kingdoms), written in 1494, contained ‘many examples of steaming or boiling human meat’. Prisoners of war were preferred ingredients but when they ran out (figuratively or literally), General Chu Ts’an’s soldiers seized women and children off the street, killed them then ate them. As recently as the nineteenth century, executioners reportedly ate the hearts and brains of the prisoners they executed, selling whatever cuts were left to the public.

Widespread epicurean cannibalism was still taking place in the late 1960s during the Cultural Revolution, although there was certainly an element of terror involved. Chinese dissident journalist Zheng Yi wrote the following in 2001:

Once victims had been subjected to criticism, they were cut open alive, and all their body parts – heart, liver, gallbladder, kidneys, elbows, feet, tendons, intestines – were boiled barbecued, or stir-fried into a gourmet cuisine. On campuses, in hospitals, in the canteens of various governmental units at the brigade, township, district, and country levels, the smoke from cooking pots could be seen in the air. Feasts of human flesh, at which people celebrated by drinking and gambling, were a common sight.

Another form of cannibalism in China had nothing to do with persecution and punishment. Chong reported that, ‘children would cut off parts of their body and make them into soup to please family members, particularly their parents’. This led him to study what he considered to be a truly unique aspect of learned cannibalism among the Chinese – its association with the Confucian philosophy of filial piety. In general terms, filial piety is a highly regarded virtue in which it is the duty of younger family members to demonstrate respect, obedience and care for their parents and elderly family members. In this case, however, it refers to an extreme act of self-sacrifice, with relatives providing parts of their own bodies for the consumption and benefit of their elders.

Although by no means a complete list, Chong used official historical records and came up with a total of 766 documented cases of such filial piety, spanning a period of over 2,000 years. The practice took place primarily between sons and fathers, sons and mothers, and daughters and mothers.2 The most commonly consumed body part was the thigh, followed by the upper arm, both of which were prepared in a rice porridge called congee. Far less frequent, but recorded nonetheless, were instances where a young person volunteered a part of their liver, breast, finger or even eyeball.3

In each case, the practice was intended to provide nutrition to a starving loved one or as a treatment of last resort, to afford the sufferer some medical benefit – more on medicinal cannibalism in Chapter 14.

So, is there any link between the practice of filial cannibalism in humans and that exhibited in the animal kingdom by species like mouth-brooding cichlids? One similarity is that in both instances the parent gains a benefit at the expense of the offspring. In humans, though, culture dictates that the offspring consciously initiate the act of filial cannibalism.

In addition to the historical record of cannibalism contained within China’s dynastic histories, the behaviour in its various incarnations is also abundantly documented in plays, poems and other works of fiction. For example, the fifteenth-century play Shuang-zhong ji (Loyalty Redoubled) tells of a general coming up with the idea of turning his concubine into soup to feed his besieged and starving troops. Happily, for the general at least, the concubine volunteers for this duty, thus sparing the general from having to murder an innocent woman. The concubine’s devotion spurs the soldiers to fight on, which leads another servant (this one a boy) to volunteer his own body.

According to numerous sources, then, the practice of cannibalism in China was more or less accepted as a necessity during times of famine, as a right to be exercised during warfare and acts of vengeance, and as a way of honouring one’s relatives. Similarly, there appear not to have been such widespread taboos regarding the behaviour as there are in the West.

But if I’ve given you the impression that cannibalism did not occur in the West, that would be an error. It was actually a common practice in Europe, where it was carried on in various forms into the twentieth century. It is also being practised today in the United States.

Footnotes

1 These authors include Jasper Becker, Key Ray Chong, Yang Jisheng, Lewis Petrinovich and Zheng Yi.

2 Rarely, this exchange took place between daughters-in-law and fathers-in-law, and between daughters-in-law and mothers-in-law.

3 Although ‘an official edict in 1261 banned cutting out the liver or plucking out the eyeballs’.