TOO MUCH TO SWALLOW: PLACENTOPHAGY

‘It gave me the wildest rush.’

The Placenta Cookbook, New York magazine

THUMBING THROUGH AN ISSUE of New York magazine three years ago, I stopped at what appeared to be a recipe feature by the alliteratively named Atossa Araxia Abrahamian. Across a two-page spread was a photo of what looked to be a veiny roast beef, bobbing in a black enamelled stew pot. Floating alongside the softball-sized steak was a sliced jalapeño, a walnut-sized chunk of ginger and a halved lemon. I read the title of the article – ‘The Placenta Cookbook’ – realising that the main ingredient in this particular dish wasn’t beef at all.

Throughout the article there were quotes from several women, each of whom was enthusiastic about having consumed her own placenta. ‘Perfect … beautiful … precious’, gushed one woman who had tried it. I also learned that, while some mothers preferred their placenta raw, others favoured placenta smoothies, placenta jerky and even a particularly apt version of a Bloody Mary. For those turned off by the idea of turning their placentas into a meal, or even handling the organ themselves, there were professional placenta-preparers who could be hired to procure the placenta from the hospital or accept its delivery by mail. They would then transform it into a bottle of encapsulated nutritional supplements, thus placing the whole placentophagy experience on a par with popping a vitamin pill. On that note, the article included an illustrated handy section for readers wondering how these ‘happy pills’ were made, leading from ‘Step 1: Drain blood and blot dry …’ to ‘Step 5: Grind in blender and pour placenta powder into pill capsules’.

From a biological viewpoint, the first question is, obviously, what is the function of a placenta? As a zoologist I was interested in determining what other mammals ate their own placentas and why they did it. There were claims from some midwives and alternative health care advocates that placenta consumption brought therapeutic benefits. What were these supposed benefits and, more importantly, was there any proof that they existed? I was also interested in determining whether additional human body parts had been (or were being) ingested for medicinal reasons. Finally, there was the inevitable question: What did placenta taste like?1

Advocates of placentophagy are likely to find it more than coincidental that the word placenta is derived from the Greek plakous, or flat cake. The Latin term placenta uterine, or uterine cake, was coined by the Italian anatomist Realdo Colombo. Tempering any culinary enthusiasm is the likelihood that the sixteenth-century scientist was referring to the flattened or slab-like nature of the roughly discus-shaped organ and not its potential as a base for chocolate frosting and candles.

The placenta is the organ that gives more than nine out of ten mammals (or roughly 4,000 species) their classification as placental mammals. Also known as eutherians, the oldest placental mammals date from around 160 million years ago. Mouse-like, they generally kept out of sight while the dinosaurs ran the show. But using their relatively larger brains and enhanced thermoregulatory abilities, they carved out slender niches of their own. Then, approximately 65 million years ago, as the planet underwent cataclysmic environmental changes, mammals hunkered down and survived. Once the dust settled, mammals exploded in diversity, spreading rapidly across a planet suddenly filled with evolutionary opportunity.

Within approximately 10 million years of the dinosaurs’ demise, mammals diversified into the existing mammalian orders – rodents, bats, carnivores, primates, etc. Some took to the air while others returned to the water – each group evolving and passing on its own suite of adaptations, like wings or fins, to supplement basal mammalian characteristics like hair and bigger brains. Many of these species went extinct themselves. Others thrived, eventually out-competing many of the non-mammalian vertebrates that had also survived the great die-off. And except in isolated regions like Australia and South America, the eutherians even outcompeted the older, non-placental mammals – the marsupials and the egg-laying monotremes.2

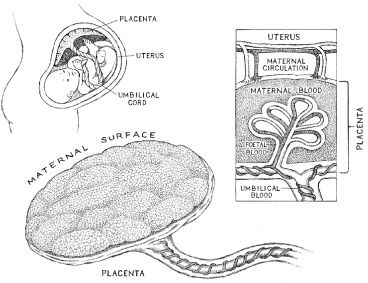

The organ that gives placental mammals their name is transient in nature, undergoing its entire, rapid development only after conception. The tissue is derived from the foetus, as opposed to the mother, and in humans it has an average diameter of about nine inches. Thickest at its centre (up to an inch), it thins out towards the edges and weighs in at just over a pound. The placenta functions as an interface between the mother and the developing foetus, connecting it to the mother’s uterine wall but acting as a buffer as well. The organ itself is richly vascularised, which gives it its dark reddish-blue to crimson colour and relates to its life-support function: carrying oxygen and nutrients from the mother to the foetus via the umbilical artery. Structurally, most of the placenta is composed of cells called trophoblasts, which have a dual role. Some form small cavities that fill with maternal blood, thus facilitating the exchange of nutrients, waste and gases between the foetal and maternal systems. Other trophoblasts specialise in hormone production. Waste products and carbon dioxide travel from the foetus back to the placenta via the umbilical vein.

The placenta has additional functions, which include the production and release of several hormones, including oestrogen (which maintains the uterine lining during pregnancy) and progesterone (which stimulates uterine growth as well as the growth and development of the mammary glands). It also prevents the transfer of some, but not all, harmful substances – blood-borne pathogens for example – from the mother to the developing foetus. Finally, the placenta secretes several substances that effectively cloak the developing foetus from the mother’s immune system – similar to the way immunosuppressant drugs prevent the body from rejecting a transplant.

Given its essential role in foetal development, the human placenta experiences after delivery what must surely amount to a precipitous fall from grace. Expelled by the uterine contractions associated with childbirth, this complex and amazing structure becomes a biohazardous ‘afterbirth’ faster than you can scream, ‘PUSH!’

In the vast majority of mammals, though, the newly delivered placenta serves one last purpose.

IN 1930, PRIMATOLOGIST Otto Tinklepaugh took a break from his groundbreaking study on chimpanzee vaginal plugs to co-author an article on the birth process in captive rhesus monkeys. He noted that the monkeys, and just about every other terrestrial mammal except humans and camelids, consumed their own placentas after giving birth. More recently, the behaviour in the animal kingdom has been studied in rodents, lagomorphs, carnivores, primates and most hoofed mammals.

Mark Kristal, the world’s foremost authority on placentophagology (and until recently the only one), began research into the subject over four decades ago. His work supports the hypothesis that, since placenta eating has been observed in such a variety of mammals, it probably evolved independently and in response to one or several survival challenges.

Kristal and his colleagues initially posited that eating the placenta kept the birthing area sanitary while eliminating smells that might attract predators. The fact that chimps giving birth in the trees hung around to eat their placentas, instead of simply moving off (or flinging them down on some cheetahs), suggested that a new hypothesis was needed. Answering the call, dietary researchers suggested that it replenished nutritional losses associated with late-stage pregnancy and delivery. Endocrinologists hypothesised that mothers might be acquiring and replenishing hormones present in the afterbirth. Other researchers suggested that placentophagy satiated a mother’s hunger after the delivery, or demonstrated the new mothers’ tendency to develop ‘voracious carnivorousness’ after giving birth.

Kristal was sceptical, and set out to investigate placentophagy in non-humans using lab rats. Their results supported none of the previous hypotheses, though Kristal did suggest that the previously proposed functions might provide secondary benefits, if they existed at all.

‘The main thing that we found during our studies turned out to be an opiate enhancing property,’ Kristal said. He explained that placenta consumption by new rat mothers appeared to increase the effectiveness of natural pain-relieving substances (opioid peptides) produced by the body. He added that these enhanced analgesic effects lasted throughout the litter’s delivery period – an important point since rats generally give birth to between seven and ten kittens at a time.3

Kristal also told me that the results of a second set of experiments linked afterbirth consumption in rats to a form of reward for parental care. Briefly, the central nervous system, pituitary gland, digestive tract and other organs secrete pain-blocking peptides like endorphins, enkephalins and dynorphins, which have been used to explain terms like ‘runner’s high’ and ‘second wind’, as well as the phenomenon in which gravely wounded individuals report feeling little or no pain. Kristal’s experiments indicated that those mothers who consumed their afterbirth received enhanced benefits from these natural painkillers, essentially getting an anaesthetic reward for initiating maternal behaviour like cleaning their pups.

I asked Kristal how long humans had been practising placentophagy and how widespread the process was.

‘I haven’t discovered any human cultures where it’s done regularly,’ he told me. ‘When placenta eating is mentioned, it’s usually in the form of a taboo. You have cultures saying things like “Animals do it and we’re not animals, so we shouldn’t do it.”’

In 2010, researchers at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, searched an ethnographic database of 179 preindustrial societies for any evidence of placenta consumption. Searching the terms ‘placenta’ and ‘afterbirth’, they found 109 references related to the special treatment and/or disposal of placentas. The most common practice, seen in 15 per cent of accounts, was disposal without burial (examples include throwing it into a lake), followed by burial (9 per cent). The latter narrowly beat out my personal favourite ‘hanging or placing the placenta in a tree’ (8 per cent). What the UNLV researchers did not find was a single instance of a cultural tradition associated with the consumption of placentas by mothers, or by anyone else for that matter.

Considering the ubiquitous nature of placentophagy in mammals, including chimps, our closest relatives, I was surprised they were unable to find any culture at all where placentas were regularly eaten. I mentioned to Kristal that I’d run across an example of placentophagy in the Great Pharmacopoeia of 1596, wherein Li Shih-chen recommended that those suffering from ch’i exhaustion (whose embarrassing symptoms included ‘coldness of the sexual organs with involuntary ejaculation of semen’) partake in a mixture of human milk and placental tissue.

‘It is an ingredient in herbal medicine,’ Kristal said. ‘In fact, there are a lot of placentophagia/midwife/doula4 websites where two things come up repeatedly. One – the benefits that I found in my research, which we never extrapolated to humans, and two – the [mistaken] idea that it’s been done for centuries in China.’

He explained that in reality this was only rarely the case, and we don’t know if it works. In terms of Chinese medicine, there are literally thousands of preparations, the efficacy of which has never been tested empirically.

On a more recent note, I had also come across a report that in rural Poland in the mid-twentieth century, peasants ‘dry [placenta] and use it in powdered form as medicine, or the dried cord may be saved and given to the child when he goes to school for the first time, to make him a good scholar’. I ran this by a Polish colleague, who did a bit of investigation himself. The answer came back ‘nie’, with my friend telling me it was probably safe to assume that the iPad had overtaken the uCord as an educational tool.

‘So why is placenta-eating becoming more popular in the US?’ I asked Kristal.

He cited two trends, one from the sixties and seventies and one current. The first had a lot to do with a kind of back-to-nature, hippie-commune philosophy. However, he lays the responsibility for the new fad on the midwives and doulas who spread the word about the positive female health benefits.

The evidence, when you try to track it down, is more anecdotal than scientific. To learn why people were currently eating their own placentas, I contacted Claire Rembis, the owner/founder of Your Placenta, a one-stop centre for all of your placental needs. Working from her home in Plano, Texas, Rembis not only offers the standard placenta encapsulation services but will also prepare placenta skin salves, placenta-infused oils and placenta tinctures, which she describes as ‘organic alcohol’ in which a mother’s placenta has been soaked for six or seven weeks. Additionally, there’s placenta artwork, in which a client’s placenta can be used to make an impression print (balloons and flowers seem popular, with the umbilical cord standing in quite nicely for the balloon string or flower stem). During the impression-making process, vegetable- and fruit-based paints are dabbed on to the placenta, which is then pressed between a clean surface (like baby’s changing pad) and a piece of heavy art-stock paper. Immediately after its modelling gig, the placenta is rinsed off and undergoes further preparation in order to assume its rightful place within a gel capsule. For those mothers who want to keep their placenta closer to their hearts, Claire also makes necklaces – tiny, stoppered bottles, full of ‘placenta beads’ (a secret formula) and available with or without gemstones.

Soon after an introductory email, Claire invited me down to Dallas. I thanked her but declined, explaining that I hoped a phone interview would suffice.

‘Well, if you’re ever in Texas, I’d be happy to prepare one for you,’ she responded.

Wait a minute, I thought as I read her email. Was she inviting me down to Texas to eat placenta?

I followed up.

She was.

‘I’ve got some of my daughter’s placenta in the freezer right now,’ Claire said.

With an offer like that on the table, how could I refuse?

I PULLED UP to the Rembis house a little after 6 p.m. with a bagful of camera gear and a bottle of Amarone. (Surprisingly, the clerk at a local liquor store had no idea what wine would go well with placenta.) Claire’s husband, William, had previously narrowed my menu choices down to placenta fajitas with hatch pepper and cilantro rice or placenta osso bucco with sides. I opted for the Italian.

Seconds after chef William ushered me into their ranch home in a quiet suburban neighbourhood, I was hit by a wall of their ten children.

I decided to interview Claire on her front lawn and she politely told her kids to remain inside, the older ones charged with keeping the little ones occupied.

I asked her what had got her interested in consuming placenta.

She explained that she had heard about the experiences of other mothers from the homebirth midwives she had begun working with when having her seventh child. Her midwife, who had been practising since the seventies, explained to her that the placenta was one of things she used to help with problems like post-birth haemorrhaging. (Since midwives can’t prescribe medicines like a doctor, they can only use natural remedies to help moms when they have issues at home.) So she decided to try it for herself.

I asked Claire what specific health benefits she thought she was getting from consuming placenta. She responded by first telling me that she’d initiated her own research study to investigate just such questions. So far, Claire had interviewed over 200 mothers but chose to speak about only those benefits that she herself had experienced. She also said that, because she hadn’t started consuming her placentas until her seventh pregnancy, she had established a baseline against which to compare her own experiences. Claire explained that after each of her first six births she’d gone through ‘the baby blues’, which she attributed to the hormonal drop caused by the loss of her placenta.

‘The first thing I noticed after taking placenta products [capsules] was the energy. I felt very energetic. The most significant thing, though, was not feeling like I was on an emotional yoyo – one minute crying, the next minute happy. Any mom knows exactly what I’m talking about, and it was the thing I dreaded most about having children. Consuming my placenta made me feel a little bit more normal – like I did when I was pregnant but before giving birth.’

Claire went on to tell me that what really convinced her that there were benefits was the fact that she’d get ‘emotional and out of sorts, and weepy and cranky, when it was time for another pill’. When she took one, she said, those emotions levelled out.

‘With my eighth child I was severely anaemic, both while pregnant and post-partum.’ She recounted that her haemoglobin counts were low and that rather than taking the iron pills typically prescribed by doctors, she took her placenta pills instead. She also pointed out that she prepared her pills from raw placenta, ‘so that you’re not losing so many of the nutrients’ from the cooking process. ‘By two weeks post-partum my haemoglobin was just below ten [grams per decilitre].’ Normal values for an adult woman are twelve to sixteen.

Next, I asked Claire if there was any evidence for the positive benefits she’d spoken about. She immediately brought up Mark Kristal’s papers. ‘Granted,’ she said, ‘his research is mostly with mice [rats, actually]. There is, you know, no professional, scientific research in humans right now. Not truly scientific research.5 What I’m doing [gathering information on placentophagy] isn’t scientific. I’m interviewing and getting feedback from moms.’

In Claire’s view this list was certainly an acceptable alternative to the evidence a more formal scientific study might provide.

When we came to discuss the potential toxicity of the placenta, I told her that I had read about studies in which placental tissue from infected mothers also contained hepatitis-, herpes- and AIDS-infected cells, and she agreed that under certain circumstances, consuming the placenta was not a good idea. She told me that to avoid coming into contact with pathogens her contract had a clause stating that clients were unaware of having any blood-borne diseases.

I posed the same question to Claire as I had to Mark Kristal. Why did she think there was currently so much interest in placentophagy?

‘People try it and it works for them. Then they tell their friends. It’s just spreading like a virus.’

In short order, William and his son Andrew returned with the supplies and so we headed inside and into the kitchen. Team Placenta quickly split their organ-related duties – he dicing veggies near the stove, she disinfecting the sink-side counter before covering the surfaces and adjacent floor with the aforementioned baby changing pads. Once the place had been sanitised and covered in absorbent blue, Claire carried over a medium-sized Tupperware container. Prying off the lid, she revealed a roughly Frisbee-shaped organ that was perhaps seven inches across and half an inch thick. (It was smaller than I was expecting.)

‘You won’t be eating this one,’ Claire told me, since it belonged to a client. She gestured to a bed of ice in the sink that held up a small baggie containing what looked to be several strips of calves’ liver. ‘That’s mine,’ she said.

‘And I’ll be cooking it up for you,’ William chimed in happily. Now clad in an embroidered chef’s apron, he was chopping away at carrots and tomatoes. ‘All organic,’ he assured me (and thank goodness for that).

Wearing disposable gloves, Claire placed her client’s placenta on a pad, unfolded it a bit and allowed me to move in for a peek. The surface was irregularly shaped and reminded me more of scrambled eggs than of an organ (albeit liver-coloured scrambled eggs holding clots of bluish blood).

‘This side faced the wall of the uterus,’ Claire told me as she de-clotted the irregular surface. She spent several more minutes examining the placenta carefully (seemingly looking for defects) before gently flipping it over like a large bloody pancake. This side was smooth, dark blue and glistening. A fan of large blood vessels ran from the periphery, converging on a twelve-inch section of umbilical cord and winding around it like the stripes on a barber’s pole.

I turned my attention to William, who was sweating vegetables in a sauté pan. He added a little beef stock, allowing the flavours of the tomatoes, garlic and onions to mingle as the veg softened. A minute or two later he retrieved the baggie containing his wife’s placenta from its ice bath and emptied the bloody slivers onto a paper plate and into the pan. Within seconds the kitchen was filled with an aroma that reminded me of beef.

The thin strips coiled up during the cooking process, now looking a bit like larger versions of the bacon chunks in a can of pork and beans, but without the fat. William added about a quarter cup of the Amarone – the steam rising as the placenta simmered.

It smelled delicious.

Two or three minutes later, William plated my placenta osso bucco and passed me the dish. Without hesitation, I took a forkful – making sure to skewer two of the four bite-sized pieces. Placing Claire Rembis’s placenta into my mouth, I started chewing.

BEFORE EXPERIENCING PLACENTOPHAGY first-hand I had done some research into what human flesh might taste like. I was somewhat puzzled at the scarcity of credible reports, although a number of notable cannibal crazies had been perfectly happy to discuss the topic.

The term ‘long pig’ has become the most popular reference point to describe the supposed pork-like taste of human flesh. The oldest reference I could find comes from a letter written by Revd John Watsford in 1847 describing the ritual cannibalism practised by the inhabitants of the Marquesas, a group of approximately fifteen Polynesian islands located around 850 miles north-east of Tahiti. But while the letter does represent the translation of a Polynesian term for the use of human flesh as food, there is no real mention of how it tasted.

The Somosomo people were fed with human flesh during their stay at Bau [a tiny Fijian islet], they being on a visit at that time; and some of the Chiefs of other towns, when bringing their food, carried a cooked human being on one shoulder, and a pig on the other; but they always preferred the ‘long pig’, as they call a man when baked.

More reliable support for the pork hypothesis came from the infamous cannibal Armin Meiwes, who is currently serving a life term for killing and devouring Bernd Brandes. The latter, a forty-two-year-old computer technician, answered Meiwes’s cannibalism chat room post in 2001. It was the perfect match, with Meiwes obsessed with cannibalism and Brandes fixated on being eaten. Shortly after entering Meiwes’s dilapidated house in Rotenburg, the recently acquainted pair decided to sever Brandes’s penis, which they reportedly tried to eat raw. Finding it too tough and chewy, they resolved to cook the wiener but ended up burning it – Meiwes eventually feeding it to his dog. Brandes, nearly unconsciousness from a combination of blood loss and the pills and alcohol he’d swallowed, eventually died – helped along by the knife-wielding Meiwes. The internet’s first cannibal killer then dismembered his counterpart. He stored the body parts in a freezer and consumed them over the course of several months.

‘I sautéed the steak of Bernd, with salt, pepper, garlic and nutmeg,’ Meiwes told interviewer Günter Stampf. Reportedly, Meiwes ate more than forty pounds of Mr Brandes during the months following the killing. ‘The flesh tastes like pork, a little more bitter,’ he said, noting that most people wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference. ‘It tastes quite good.’

The pork comparison, however, was not shared by all.

Issei Sagawa, an unrepentant Japanese cannibal who murdered and ate a female Dutch student in 1981 (and got away with it because of powerful family connections), compared his victim’s flesh to raw tuna.6

In the 1920s, New York Times reporter William Seabrook set out to eat a chunk of human rump roast with some Guero tribesmen in West Africa. Upon returning home he began writing a book about his adventures. Depending on what source you believe, either Seabrook discovered that the tribesmen had tricked him into eating a piece of ape, or they had simply refused to share their meal with him. With the validity of his book in jeopardy, Seabrook set out to procure some real human flesh – this he claimed to have gotten from an orderly in a Paris hospital who had access to recently deceased patients. Seabrook says that he cooked the meat over a spit – seasoning it with salt and pepper and accompanying it with side of rice and a bottle of wine. It did not taste like pork, he said, ‘It was good, fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef.’

IN PLANO, TEXAS, the Rembis family stood by waiting for my reaction, I took my time, chewing Claire’s placenta slowly. The first thing that came to mind wasn’t the taste – it was the texture. Firm but tender, it was easy to chew. The consistency was like veal.

The taste, though, had none of its delicate, subtly beefy flavour. It was definitely dark meat, organ meat, but it wasn’t exactly like anything I’d ever eaten before, though it faintly reminded me of the chicken gizzards I used to fry up as a student. It had a strong but not overpowering flavour ‘It’s very good,’ I told the assembled Rembis clan and they responded with a chorus of moans, groans and giggles.

So is there any real benefit to this practice? If one were to gauge the benefits by the number of societies that practise placentophagy, the answer would be a resounding ‘No’.

Maggie Blott, a spokeswoman for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, believes that there’s no medical justification for humans to consume their own placenta. ‘Animals eat their placenta to get nutrition,’ she told a BBC journalist, ‘but when people are already well-nourished, there is no benefit, there is no reason to do it.’

But what about the alternative scenario – that consuming placentas could possibly have detrimental effects?

According to Kristal, ‘The sharp distinction between the prevalence of placentophagy in non-human, non-aquatic mammals, and the total absence of it in human cultures, suggest that different mechanisms are involved. That either placentophagia became somehow disadvantageous to humans because of illness or sickness or negative side effects, or something more important has come along to replace it.’

Ultimately, though, the possibility of negative effects and the lack of evidence for beneficial effects doesn’t faze people like Claire and William Rembis and, similarly, it didn’t prevent Oregon representative Alissa Keny-Guyer from sponsoring bill HB 2612, which was passed unanimously by the state Senate in 2013. The new law allows Oregon mothers who have just given birth to bring home a second, though slightly less joyous, bundle when they leave the hospital.

Except in rare cases, it appears that medicinal cannibalism is no more or less than a harmless placebo. But, if that’s true, then beyond our culturally imposed taboo, maybe there exists another reason why we don’t indulge in cannibalism on a more regular basis. Recalling that UNLV researchers found no mention of placentophagy in the 179 societies they examined, I wondered if perhaps these groups knew something that ritual cannibals, proponents of medicinal cannibalism and modern placentophiles have missed.

Footnotes

1 A 2013 study conducted by researchers at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, of women who had ‘ingested their placentas after the birth of at least one child’ found that they were most likely to be white, married and middle-class.

2 Currently, there are five species of monotremes (four echidnas and the platypus) and 334 species of marsupials. The latter are commonly referred to as ‘pouched mammals’, although a pouch, or marsupium, is not a requirement for entry to the marsupial club. What all marsupials do share is a short gestation period, after which the foetus-like newborn takes a precarious trip from the vaginal opening to a teat (usually found within the marsupium). Upon finding one, the tiny creature latches on for dear life, and continues what is essentially the remainder of its foetal development for additional weeks or even months.

3 Yes, rat babies are known as kittens (which should make dog lovers smile). The largest kitty litter I was able to uncover is twenty-six – presumably a tough number for the fourteen baby rats that didn’t immediately latch on to their own nipple.

4 A doula (from the Ancient Greek for ‘female servant’) is a non-medical person who assists the mother before, during and after childbirth. After reportedly engaging in turf-battles with medical personnel, some hospitals banned doulas while others encouraged them – presumably in an effort to reduce the number of birthing-room-related fistfights.

5 In a 1954 study, Czech researchers claimed that placenta consumption increased lactation in post-partum women having lactational difficulty (compared to a control group fed beef). According to Mark Kristal, though, ‘this study does not conform to modern-day ideas about scientific methods or statistical analyses’. He noted that ‘the experiment was methodologically flawed’ and that the hormones responsible for increased lactation would have been denatured in the preparation they described.

6 On the topic of Meiwes and Sagawa (albeit briefly), some readers may be wondering why I’ve essentially steered clear of the criminal cannibalism typified by this pair and their ilk. One reason is that the topic has been covered in sensational (and often gory) detail in a number of previous books. More importantly, though, several of these psychopaths are still alive (or recently deceased) and out of respect for the families and loved ones of their victims, I have chosen not to provide these murderers with anything that could even vaguely be interpreted as acclaim.