NO LAUGHING MATTER: CANNIBALISM AND KURU IN THE PACIFIC ISLANDS

Nothing it seems to me is more difficult than to explain to a cannibal why he should give up human flesh. He immediately asks, ‘Why mustn’t I eat it?’ And I have never yet been able to find an answer to that question beyond the somewhat unsatisfactory one, ‘Because you mustn’t.’ However, though logically unconvincing, this reply, when backed by the presence of the police and by vague threats about the Government, is generally effective in a much shorter time than one could reasonably anticipate.

J. H. P. Murray, Papua; or British New Guinea

IN THE SPRING OF 1985, veterinarians working in Sussex and Kent were puzzled when dairy farmers reported that a few of their cows were exhibiting some peculiar symptoms. The normally docile creatures were acting skittish and aggressive. They also exhibited abnormal posture, difficulty standing up and walking and a general lack of coordination. Most of the cows were put down and sent on to rendering plants – facilities that process dead, often diseased animals into products like grease, tallow and bonemeal. It wasn’t until the following year that the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food launched an investigation.

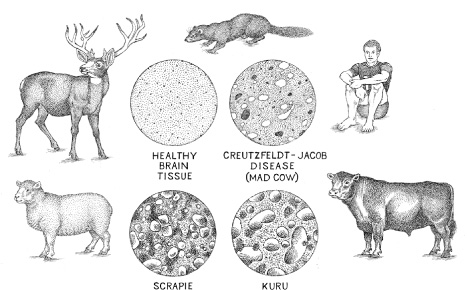

According to research biochemist Colm Kelleher, microscope slides were prepared from the brains of stricken cows and they showed the tissue to be riddled with holes, like Swiss cheese. But the veterinary pathologists who examined the slides blamed the holes on faulty slide preparation. By November of the following year, however, researchers knew that the abnormal spaces had once been filled with neurons that had shrunk and died. They also thought that the sticky concentrations of brain protein might be a contributing factor to the neuron deaths. The holes and plaques were characteristic of a number of neurological diseases, with sheep scrapie and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) being the best-known of these. These and other similar diseases were classified as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) because of the spongy appearance of infected brain tissue. The new disease soon had a name: Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), or ‘Mad Cow Disease’ to the press.

By 1987 there were approximately 420 confirmed cases of BSE, which had spread to cattle herds across England and Wales, and while scientists looked for answers, nervous government officials repeatedly reassured the public that it was safe to eat British beef. And why not, they rationalised; hadn’t scrapie been killing sheep for centuries with no harm to the humans who consumed them? Why, then, should a bovine version of the disease be any different?

Other researchers, though, were not so sure, and a few of them began comparing BSE to a disease that had killed humans – thousands of them. To these professionals, this particular affliction was still known by its indigenous name: kuru, the trembling disease.

And kuru was spread by cannibalism.

IN THE EARLY 1950S, anthropologists and medical researchers began arriving at one of the wildest and most primitive regions on the planet, New Guinea, the world’s second-largest island. Upon their arrival, the scientists saw no roads. Instead they were found themselves crossing parasite-ridden mangrove swamps and rainforests whose primary inhabitants seemed to be biting insects, terrestrial leeches and venomous snakes. But even after reaching their destination in the foreboding Eastern Highlands, conditions were no less dangerous, for the researchers had come to study New Guinea’s infamous cannibals.

Numbering approximately 36,000 in the mid-twentieth century, the Fore (pronounced for-ay) spoke three distinct dialects and inhabited some 170 villages situated among New Guinea’s lush mountain valleys. Desiring and having little or no contact with the outside world, the Fore practised the same slash-and-burn agriculture that had sustained them for thousands of years. Currently what made them especially interesting to researchers was not their lack of contact with the modern world, their farming techniques, or even the reports that they practised ritual cannibalism. It was the fact that something was killing them – horribly and at an alarmingly rapid rate.

Decades earlier, as colonialism extended its reach to the Pacific islands following the Great War, Australian patrol officers in New Guinea began encountering some of the most isolated of the island’s inhabitants.1 Like the missionaries who had arrived, preached, and often disappeared for their troubles, the Australian officials (whom the Fore called kiaps) encouraged the locals to curtail what they considered bad behaviour. Sorcery and tribal warfare, the Aussie officials said, were prohibited. The Fore were also kindly requested to stop eating each other, a practice that formed part of their funeral rituals to honour their dead. The indigenous people seemingly soon agreed to the requests, though today many anthropologists believe that some simply concealed their long-held rituals whenever the white people were around.

Meanwhile, the kiaps started to notice something akin to a plague taking place, one that took its primarily toll on the island’s women and children. In addition to uncontrollable laughter, victims of the affliction experienced tremors, muscle jerks and coordination problems that gradually gave way to an inability to swallow and finally, complete loss of bodily control. The Fore responded to their stricken relatives with kindness – feeding, moving and cleaning them when they could no longer care for themselves. Invariably, though, their loved ones died – all of them – of starvation, thirst, or pneumonia, their bodies covered in sores. The mystery disease was killing approximately 1 per cent of the population each year.

Fore elders told the Australians that the sickness resulted from a form of sorcery: sorcerers would stealthily obtain an item connected to their intended victim, like faeces, hair, or discarded food. After wrapping the object in leaves, they would place it in a swampy area where it couldn’t be found. As the sorcery bundle began to decompose so, too, the Fore said, would the victim. The elders also claimed that the condition could not be cured or even treated, and they tried to explain that preventing this sort of thing was the main reason they sometimes killed each other. The unfortunate ones accused of such sorcery, without evidence, were generally men or boys, usually several days after someone in their own village had died of kuru. They were then hacked, stoned or bludgeoned to death in a form of ritual murder known as tukabu.

To the Australians, the best way to stop the killing was to gain an understanding of the mystery ailment, and a number of hypotheses were developed. Initially, it was suggested that the deaths were stress-related and had resulted from the Fore making contact with the whites. Others, though, feared that whatever was killing the Fore had a more pathological nature.

By the time Ronald and Catherine Berndt arrived in the New Guinea highlands in 1951, they had already spent years in the field studying Australia’s aboriginal communities. At first, the indigenous highlanders threw parties for the couple, reportedly believing them to be the spirits of their dead ancestors, returning to the fold to relearn the language they had apparently forgotten. Soon enough, though, the Fore lost interest in rehabilitating their pale relatives – but not in the strange goods they had brought along with them. Fascination soon turned to envy and not long after the Berndts settled in, they wrote that the locals were ‘difficult people to deal with’, requiring ‘payments for stories: salt, tobacco, newspapers, wool strands, matches, razors, and so on’. The anthropologists also reported ‘plenty of cannibalism’.

‘Actually these people are “bestial” in many ways,’ Ronald Berndt wrote. ‘Dead human flesh, to these people is food, or potential food.’ He also described cannibalism among the Fore as an outlet for sexual violence, employing the phrase ‘orgiastic feast’.

A decade later, the not-yet-controversial anthropologist Bill Arens commented on Ronald Berndt’s influential 1962 book on social interactions among the Fore. According to Arens, Berndt’s Excess and Restraint displayed ‘too much of the former and too little of the latter’. Arens was particularly galled by the description of a Fore husband copulating with a corpse as the man’s wife simultaneously butchered the body for a meal. As these things go, she accidentally cut off her husband’s penis with her knife. ‘Now you have cut off my penis!’ the man cried. ‘What shall I do?’ In response, according to Berndt, the woman ‘popped it into her mouth, and ate it’.

Arens was not alone in his criticism of the Berndts, as others concluded that while the pair had made some important anthropological contributions, there were more than a few problems with their work, not least the many instances of outrageous behaviour Berndt detailed in his book – coupled with the growing suspicion that he had made much of it up.

Fortunately, following the Berndts’ inauspicious studies, a new group of researchers arrived in the late fifties. Daniel Carleton Gajdusek (Guy-doo-shek), a Yonkers, New York, native, graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1946. Gajdusek had no real interest in practising medicine but instead chased his fascination with viral genetics and the anthropology of so-called ‘primitive’ communities across the world. He studied rabies and plague in the Middle East, hemorrhagic fever in Korea and encephalitis in the Soviet Union. Arriving in Melbourne in 1955, the brilliant but eccentric researcher frequently ‘went bush’, studying child development among the aboriginals and collecting blood serum for several Australian research labs.

Gajdusek flew to New Guinea in 1957 and, with nothing but his own meagre funds to support this venture, he began working on a new problem. To a colleague in the United States, Gajdusek wrote:

I am in one of the most remote, recently opened regions of New Guinea, in the center of tribal groups of cannibals, only contacted in the last ten years – still spearing each other as of a few days ago, and cooking and feeding the children the body of a kuru case, the disease I am studying – only a few weeks ago.

But Gajdusek had never seen any actual cannibalism and he had very little real knowledge about kuru. Beyond the stress hypothesis, there was some conjecture that the deadly condition might be the result of an environmental toxin. Others believed that kuru was a hereditary disorder. Consequently, Gajdusek got busy. He spent months collecting blood, faeces and urine from the locals. He ran tests on those stricken by the disease and, with the aid of translators, he conducted interviews with victims and their family members.

By mid-1957 Gajdusek was working with Vin Zigas, a medical doctor who had already been gathering information, as well as his own blood samples. That November their initial findings were published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. Kuru, the authors claimed, was a degenerative disease of the central nervous system. They described the clinical course of the disease as well as its curious preference for striking three times as many women as men. The skewed sex ratios were difficult to pick up, however, since more men were being killed for having been kuru sorcerers. For the Fore, ritual murder had become the great equaliser. Significantly, Gajdusek also noted that kuru occurred equally in children of both sexes.

The researchers sent off blood and tissue samples for analysis but the results showed no evidence of viral infection, nor did they appear to indicate the presence of a toxin (they had suspected that the Fore were being poisoned by heavy metals in their diet). But a number of the tissue specimens did show something remarkable. After examining the brains of eight kuru victims, scientists at the National Institute of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, reportedly found no evidence of inflammation or any immune response whatsoever. That meant the victim’s body had not been fighting off a pathogenic organism like a virus, bacterium or fungus. In most cases, at the first signs of a viral, bacterial or fungal intruder, the body initiates a sustained, multi-pronged defence consisting of responses like swelling and inflammation, cell-mediated responses (like an attack by white blood cells), and the production of antibodies – proteinaceous particles that bind to surface proteins found on foreign cells and viruses.

What the investigators did find, however, was that large regions of the cerebellum (which sits like a small head of cauliflower behind the cerebral hemispheres) were full of holes.

Igor Klatzo, a NIH researcher, had seen a disease like this only once before. The closest condition he could think of was that described by Jakob and Creutzfeldt.

Another NIH scientist noticed a similarity between kuru and the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) known as scrapie, an unusual infectious agent of sheep. Scrapie, which was present in European sheep by the beginning of the eighteenth century, was named for one of its symptoms, namely the compulsive scraping of the stricken animal’s fleece against objects like fences or rocks. It had been previously been classified as a ‘slow virus’, an archaic term for a virus with a long incubation period, in which the first symptoms might not appear for months or even years after exposure. Klatzo and William Hadlow, who had made the kuru/scrapie connection, now suspected that the cause of kuru might also be a slow virus.

At this point, Ronald Berndt stepped in, writing his own article on kuru, reemphasising the importance of sorcery and resurrecting his original hypothesis of stress causation. Fear alone, Berndt claimed, was probably enough to initiate the irreversible symptoms of kuru.

Gajdusek, for his part, dismissed Berndt’s assertions, believing instead that the high occurrence of kuru among young children argued against a psychological origin for the disease. He was leaning toward the explanation proposed by genetics professor Henry Bennett, who attempted to explain the discrepancy between male and female adults deaths.

Bennett proposed that a mutant kuru gene ‘K’ was dominant (K) in females but recessive (k) in males. Accordingly, only males who were KK (and who had inherited a dominant form of the gene from each parent) died of kuru, while males who were either normal (kk) or carriers (Kk) were unaffected by the disease. Alternatively, females who were either KK or Kk died of kuru, while only those females who were normal (kk) were unaffected.

In the end, the fact that kuru victims included equal numbers of male and female children, but few adult males, was deeply troubling to Gajdusek, and it raised serious questions about Bennett’s genetic disease hypothesis, which was soon abandoned.

Meanwhile, the condition was garnering sensational reports in the press. Time magazine, for example, opened its 11 November 1957, article ‘The Laughing Death’ with the following:

In the eastern highlands of New Guinea, sudden bursts of maniacal laughter shrilled through the walls of many a circular, windowless grass hut, echoing through the surrounding jungle. Sometimes, instead of the roaring laughter, there might be a fit of giggling. When a tribesman looked into such a hut, he saw no cause for merriment. The laugher was lying ill, exhausted by his guffaws, his face now an expressionless mask. He had no idea that he had laughed, let alone why … It was kuru, the laughing death, a creeping horror hitherto unknown to medicine.

For his part, Gajdusek hated the media coverage and he considered the term ‘laughing death’ to be a ‘ludicrous misnomer’.

The worldwide media coverage did at least increase the public’s awareness of the deadly problem facing the Fore. Because of this, universities began to funnel funds into kuru investigation and this money helped support a new influx of professional researchers into the region.

Two of the first to arrive were cultural anthropologists Robert and Shirley Glasse (now Lindenbaum), who came from Australia to New Guinea on a university grant in 1961. Studying kinship among the Fore, they returned to continue their research in 1962 and 1963. Their work in the New Guinea Highlands would ultimately allow them to make the definitive connection between kuru and cannibalism.

WHEN I ASKED Dr Lindenbaum how she had finally been convinced of the mode of kuru transmission, she explained that once the epidemic began in the New Guinea Highlands, she and her then-husband were instructed to gather genealogical data about people who had kuru. In doing so, they spoke to Fore elders who had seen the first cases of the disease in their villages.

‘They could remember these cases and even the names of the people in the North Fore who came down with the disease some couple of decades earlier. There were these tremendously convincing first stories and we said, “What happened to those people?” And the Fore said, “Well, they were consumed.” We knew they were cannibals.’

Dr Lindenbaum continued her tale.

‘We knew cannibalism was customary in this area but that the disease had only appeared in the last few decades. And so we thought, “Well, that’s very interesting.” When we began collecting ethnographic data about who ate whom, it became clear that it was adult women, not adult men, but children of both sexes. At that time the director of kuru research in New Guinea was a guy named Richard Hornabrook, a neurologist. And he said to us, “What is it that adult women and children do that adult men don’t do?” and we said, “Cannibalism, of course.” The epidemiological evidence matched the cultural/behaviour evidence, and that matched the historical origin evidence. It was such a neat package, you know?’

I nodded. ‘So what did you do with that information?’

‘We told everybody,’ she said.

‘And?’

‘And nobody believed us.’

Nevertheless, Robert Glasse published their hypothesis that kuru was transmitted by consuming the body parts of relatives who had died from the disease. As support, he cited the fact that women commonly participated in ritual cannibal feasts but not men. He also wrote that children of both sexes had become infected because they accompanied their mothers to these ceremonies and participated in the consumption of contaminated tissue, including brains. In a later study, Glasse calculated that kuru appeared anywhere between four and twenty-four years after the ingestion of cooked human tissue containing an unidentified pathogenic agent, although we now know that the symptoms may not appear until five decades after exposure.

Nearly fifty years after Glasse published the couple’s findings, anthropologist Jerome Whitfield and his colleagues used an extensive set of interviews as well as previously collected ethnohistorical data to provide a detailed description of Fore mortuary rites. Whitfield told me how his research group deployed the educated young Fore members of their team to conduct interviews in a sample group composed of elderly family members who had witnessed, taken part in, or were informed about traditional mortuary feasts.

The interviews revealed funerary practices that ranged from burial in a basket or on a platform to the practice of ‘transumption’, a term Whitfield and some of his colleagues adopted as an alternative to using ‘cannibalism’ to describe the ritual consumption of dead kin. As for how the funerary practices would be carried out: if possible, the dying person made his or her preference known. In other cases though, the deceased’s family made the call. Generally, the Fore believed that it was better to be consumed by your loved ones than by maggots and that, by eating their dead, relatives could express their grief and love, receive blessings, and ensure the passage of the departed to Kwelanandamundi, the land of the dead. For these reasons transumption was the favoured funerary practice.

According to those interviewed by Whitfield’s team, the corpse was placed on a bed of edible leaves in order to ensure that ‘nothing was lost on the ground as this would have been disrespectful’. The body was cut up with a bamboo knife and the parts handled by several women whose specific roles were defined by their relationships to the deceased. Pieces of flesh were placed into piles to be divided up among the deceased’s kin. Next, the women leading the ceremony enlisted the daughters and daughters-in-law of the deceased to cut the larger sections into smaller strips, which were stuffed into bamboo containers with ferns and cooked over a fire. Eventually, the deceased’s torso was cut open, but during this portion of the ritual the older women formed a wall around the body to prevent younger women and children from seeing the removal of the intestines and genitals. These parts were presented to the widow, if there was one. Once the flesh was cooked, it was scooped out and placed onto communal plates made of leaves. The funerary meal was shared among the dead person’s female kin and their children.

The deceased’s head also became part of the ritual. Initially cooked over a fire to remove the hair before being defleshed with a knife, the skull was then cracked with a stone axe and the brain removed. Considered to be a delicacy, the semi-gelatinous tissue was mixed with ferns, cooked and consumed. Bones were dried by the fire, which made it easier to grind them into a powder that would be mixed with grass and heated in bamboo tubes. According to the accounts obtained by Whitfield’s team, the Fore ate everything, including reproductive organs and faeces scraped from the intestines.

Shirley Lindenbaum told me that, initially at least, members of the Fore were receptive about answering questions related to kuru and cannibalism. Later though, as more missionaries and journalists came through and wanted to ask about it, they became very defensive.

So how did kuru spread from village to village and from one region of the Fore territory to another? According to Lindenbaum, kinship relations were the key. She explained that although Fore women moved from their natal homes to marry men from other groups, they still maintained their kinship affiliations with their former communities. When deaths occurred, women from adjacent and nearby hamlets who were related to the deceased travelled back to take part in the mortuary feasts. Similarly, individuals and families who moved into new communities maintained kinship ties with their former communities, especially on special occasions. Additionally, like other diseases throughout history, kuru travelled along well-defined trade/exchange routes, in this case those connecting the villages of the New Guinea Highlands.

Factors like these did much to explain how kuru had spread through the villages and additional research put a timeline on the dispersal. By tracing the path of the kuru reports, from the earliest to the latest, Lindenbaum and her husband calculated that the first cases of kuru occurred around the turn of the twentieth century in Uwami, a village in the Northwestern Highlands. By 1920 kuru had spread to the North Fore villages, and by 1930 into the region inhabited by the South Fore.

Jerome Whitfield, who conducted nearly 200 interviews in the kuru-affected region for his dissertation, believes that the practice of cannibalism in the New Guinea Highlands may have begun forty or fifty years earlier than the first cases of kuru – which would make it sometime in the mid-nineteenth century.

Eventually, these findings became strong evidence against a genetic origin for the disease – since had there been a genetic link, researchers would not have expected the first reports of kuru to begin so suddenly and only sixty years earlier. Additionally, had kuru been a genetic abnormality, in all likelihood it would have reached something known as epidemiological equilibrium, a condition in which the prevalence of a genetic disorder in a population becomes stable, rather than changing over time. In this case, the Glasses’ data indicated that, from its first appearance at the turn of the century, kuru deaths had increased over the subsequent five decades, peaking between 1957 and 1961, with around a thousand victims in total. With the prohibition of cannibalism beginning in the late 1950s, the number of kuru deaths hit a steep decline in the sixties and seventies, with fewer than 300 deaths between 1972 and 1976.

The plague was over. Or so it seemed.

Footnote

1 The Territory of New Guinea was administered by Australia from 1920 until 1975.