ONE STEP BEYOND

Hunger hath no conscience.

Anon

IN SOME WAYS, then, cannibalism seems to make perfect evolutionary sense. If a population of spiders has an abundance of males from which a female can choose, then cannibalising a few of them may serve to increase Charlotte’s overall fitness by increasing the odds that she can raise a new batch of young. On the other hand, in a population where males aren’t plentiful or where the sexes cross paths infrequently, cannibalising males would likely have a negative impact on a female’s overall fitness by decreasing her mating opportunities. As a zoologist, I find this kind of dichotomy pleasing, since it’s logical and appears to be a more or less predictable occurrence. In nature, as far as cannibalism is concerned, there are no grey areas, no guilt and no deception. There is only a fascinating variety of innocent, though often gory, responses to an almost equally variable set of environmental conditions – too many kids, not enough space, too many males, not enough food.

The real complexity and the uncertainty emerge only on our own branch of the evolutionary tree. It was here that I found cannibalism painted in equal shades of red and grey.

Sigmund Freud believed that, in humans, atavistic urges like cannibalism and incest are hidden below a veneer of culturally imposed taboos, and that the suppression of such forbidden behaviours signalled the birth of modern human society. Yet, compared to other groups such as insects and fishes, cannibalism occurs less frequently in mammals and even less frequently in our closest relatives, the primates – where most examples appear to be either stress-related or due to a lack of alternative forms of nutrition.

Though we humans do share some of our genetic makeup with fish, reptiles, and birds, we’ve evolved along a path where cultural or societal rules influence our behaviour to an extent unseen in nature. Freud believed that these rules and the associated taboos prevent us from harking back to our guilt-free and often violent animal past. Similarly, my studies have led me to conclude that the rules we’ve imposed in the West regarding cannibalism serve as constraints to practices that might otherwise be deemed acceptable if we were looking at protein-starved Mormon crickets instead of indigenous Brazilians consuming their unburied dead.

There is a considerable body of evidence that cultures that were never exposed to these taboos (like Homo antecessor) or encountered them only relatively recently (the Chinese and the Fore of New Guinea) had little issue with undertaking a range of cannibalism-related behaviours as they developed their own sets of rules and rituals. Indeed, some of these cultural mores extolled the virtues of cannibalism as an honour bestowed upon a deceased relative or a slain foe, or as a respectful way to treat a gravely ill parent. But even in societies where cannibalism might once have been a perfectly acceptable practice, given the pervasive influence of Western culture across the world today it’s unlikely that ritual cannibalism currently exists, even on a small scale.

It’s also likely that Freud would have called upon long-hidden impulses to explain our titillation with all things violent, gruesome or forbidden. But although it’s unclear to me the extent to which atavistic urges are involved, there is no doubt that we are, and have always been, fascinated by cannibalism. We need look no further than the popularity of novels like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (with its depiction of post-apocalyptic cannibalism), or even our obsession with vampires and zombies. A long list of popular films might begin with The Night of the Living Dead and its cinematic progeny, and according to Variety, 17.29 million viewers helped turn The Walking Dead’s season five premiere into the most watched cable TV show of all time. Perhaps the violent scenarios we watch and read about on a daily basis are a form of drug – one that creates excitement in lives that might otherwise be mundane and unfulfilled. According to Andrew Silke, head of criminology at the University of East London, ‘Viewing anything that involves violence or death will kick-start a lot of psychological processes, such as stress and excitement. Your brain’s neocortex becomes psychologically aroused, but not in a dangerous way since you’re in the safe environment of your own home.’ Whatever the underlying reason, our language is filled with cannibal references: a woman who uses men for sex is a man-eater, while back in the twenties and thirties a cannibal was ‘an older homosexual tramp who travelled with a young boy’. To ‘eat someone’ is a popular term for performing oral sex.

Most real-life cannibalism-related crimes are thought to stem from psychological aberrations. Forensic pathologist George Palermo believes that cannibal killers ‘are people who have a tremendous desire to destroy – a tremendous amount of hostility that they need to release. They have something stored up inside them in order to reach the point of where they want to destroy the human body and eat human flesh and they feel a need to release that violence.’ Of course, such incidents are immediately condemned, although once again they often lead to fame for the cannibal and millions of dollars in revenue for those who care to recreate their stories in books or on film.

If one goes by the examples in the media (‘Woman Dies After Cannibal Eats Her Face’; ‘Nude Face-eating Cannibal? Must Be Miami’) it would certainly seem that there are more cannibal killers out there than ever before. Even if the same percentage of cannibal killers exists now as have in the past (even the recent past), the population explosion across the planet would make it likely that their numbers are growing. Then there’s the fact that overpopulation and overcrowding are key catalysts for cannibalistic behaviour in nature. Of course, some would consider it a stretch to extrapolate human behaviour from the examples of spiders, fish or hamsters. But for a zoologist, those comparisons are far less problematic.

I believe there’s a scientific basis for outbreaks of widespread cannibalism, and the trigger could be something that has initiated it again and again throughout history.

The process of desertification is taking place right now, in the United States, in places like Texas and even California, where researchers Daniel Griffin and Kevin Anchukaitis used soil moisture to measure drought. They determined the 2012–2014 period to be the most arid on record in 1,200 years, with 2014 coming in as the driest single year. Around the globe, across vast expanses of China, Syria and central Africa, regions that only recently experienced dry seasons are becoming deserts. The populations of Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia, three of the poorest countries in the world, are suffering through the worst drought conditions in sixty years.

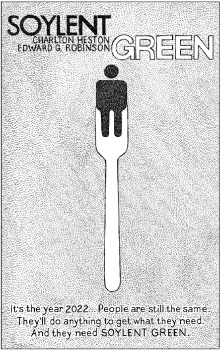

In 1973 Hollywood imagined just such an environmental disaster scenario in Soylent Green, starring Charlton Heston. His character, Frank Thorn, is a policeman in the hyper-crowded city of New York, circa 2022. Real food is now an extremely rare extravagance and most of the population subsists on nutrition wafers – including everybody’s new favourite: Soylent Green. With the aid of his old friend Sol (Edward G. Robinson, in his last role), Thorn is working to solve the murder of a rich Soylent Corporation executive.

During his examination of the crime scene, Thorn removes some ‘evidence’ from the executive’s apartment. This includes real food, a bottle of bourbon and a classified oceanographic survey, dated 2016. Sol and his cronies (a group of like-minded researchers referred to as ‘Books’) learn that the oceans are dead and therefore unable to produce the algal protein from which Soylent Green is reputedly made. They speculate on the real ingredients and the news is not good. Heartbroken, Sol shuffles off to a government euthanasia centre, downs a lethal cocktail and dies, but not before he whispers his secret into Thorn’s ear. Outside the building, the cop sneaks into the back of a truck supposedly transporting the bodies of the euthanised to a crematorium, but instead it heads straight to the Soylent manufacturing facility where Sol’s dying words are confirmed.

‘They’re making our food out of people!’ Thorn tells a fellow cop (after the requisite gun battle). ‘Next thing they’ll be breeding us like cattle.’ Seriously wounded, Thorn is carried away on a stretcher, screaming what would become the American Film Institute’s seventy-seventh most famous quote in movie history.

‘Soylent Green is people!’

Though the special effects are dated and the action is reduced to the standard ‘cop chases the bad guys’, Soylent Green remains a scary 1970s take on a world ravaged by climate change, pollution and overpopulation.

But while we should be alert to the possibility that climate change, and the likely environmental catastrophes associated with it, will almost certainly bring with them a rise in survival cannibalism, we should also look back on the role that other manifestations of cannibalism have played in our species’ history. Far from being the nightmarish aberration we tell ourselves it is – in films, novels and tabloid sensationalism – cannibalism has woven itself into our myths and legends, formed the basis of miracle cures ancient and modern, helped discipline naughty children (and entertain good ones), popped up in the Bible, fascinated anthropologists, zoologists and biologists and – sadly – played a significant role in colonialism, conquest and war. Though it might not always be immediately obvious, none of us is untouched by this most ancient and enduring aspect of life.