‘A census taker tried to quantify me once. I ate his liver with some fava beans and a big Amarone.’

Hannibal Lecter in Thomas Harris, The Silence of the Lambs

TO MARK ITS ONE-HUNDRED-year anniversary in 2003, the American Film Institute polled its members to determine the fifty greatest screen villains of all time. Topping the AFI list was the ultimate in fictionalised cannibals, Dr Hannibal Lecter, while second place went to Norman Bates, the mother-fixated hotel manager of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 classic Psycho.

While Bates’s link to man-eating may not be immediately clear, it turns out that he too had his roots in the cannibal tradition. From the film’s opening scene, Hitchcock invited audiences to confront some long-held taboos. Filmgoers titillated the previous year by the first of the Rock Hudson/Doris Day bedroom comedies suddenly found themselves transformed into voyeurs, peering into shadowy corners previously unseen by mainstream movie audiences. Psycho soon became a sensation with the public and remains so today. More than a half-century after its release, Bernard Herrmann’s strings-only score is perhaps the most instantly recognisable music ever written for a film. Less well known was the fact that Joseph Stefano’s screenplay for Psycho had been adapted from a Robert Bloch pulp novel about Wisconsin native Edward Gein (pronounced Geen), a real-life murderer, grave robber, necrophile and cannibal.

Born in 1906, Gein lived a solitary and repressed life under the thumb of a domineering mother. The family owned a 160-acre farm, seven miles outside the town of Plainfield, but when his brother died in 1944 Gein abandoned all efforts to cultivate the land. Instead, he relied on government aid and the occasional odd job to support himself and his mother. When she died in 1945, Gein found himself alone in the large farmhouse. He sealed off much of it and left his mother’s room exactly as it looked when she was alive. The house itself fell into such serious disrepair that the neighbourhood kids began claiming that it was haunted.

On the night of 17 November 1957, things began to unravel for the recluse known as ‘Weird Old Eddie’. The police were investigating the disappearance of local shopkeeper Bernice Worden when they got a tip that Gein had been seen in her hardware store several times that week. They picked him up at a neighbour’s house, where he was having dinner, and questioned him about the missing woman. ‘She isn’t missing,’ Gein told them, ‘she’s down at the house now.’

Gein’s dilapidated farmhouse had no electricity, so the cops used torches and oil lamps to pick their way through the debris-strewn rooms. In a shed in the back yard, one of the men bumped into what he assumed to be the remains of a dressed-out deer hanging from a wooden beam. But the fresh carcass hanging upside down was no deer; it was the decapitated body of Mrs Worden. As the stunned lawmen moved through the gruesome crime scene it became clear that the neighbourhood kids had been right. The Gein house was haunted. Each room they entered presented a new nightmare: soup bowls made from human skulls, a pair of lips attached to a window shade drawstring, a belt made from human nipples. In the kitchen, the police reportedly found Bernice Worden’s heart sitting in a frying pan on the stove and an icebox stocked with human organs.

Soon after Gein’s arrest, media correspondents from all over the world began descending on the town and its shocked populace. Reporters poked around the Gein farm and interviewed neighbours. Some of the locals recounted how they’d been given ‘venison’ by Gein, who later told authorities that he had never shot a deer in his life. Perhaps surprisingly, the Plainfield Butcher had also been a popular babysitter.

With the publication of a seven-page article in Life magazine (and a two-page spread in Time), millions of Americans became fascinated with Ed Gein and his crimes. Plainfield became a tourist attraction with bumper-to-bumper traffic crawling through the narrow streets.

The following year, Robert Bloch drew on the Gein crimes in his novel, relocating his tale to Phoenix and concentrating on the mother fixation while playing down the mutilation and cannibalism. An assistant gave Alfred Hitchcock the book and he procured the film rights soon after reading it. The director also had his staff buy up as many copies of the novel as they could find. He wanted to prevent readers from learning about the plot and revealing its secrets. After some initial resistance from Paramount Pictures, the ‘Master of Suspense’ directed his most famous and financially successful film – one that would never have been made if not for Ed Gein, a quiet little cannibal who explained to the authorities, ‘I had a compulsion to do it.’1

Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise, though, that our greatest cinematic villain is a man-eating psychiatrist while the mild-mannered runner-up is based on a real-life cannibal-killer. Particularly if we consider that many cultures share the belief that consuming another human is the most heinous act a person can commit. As a result, real-life cannibalistic psychopaths like Jeffrey Dahmer (another Wisconsin native) and his Russian counterpart Andrei Chikatilo have attained something akin to mythical status in the annals of history’s most notorious murderers. These tales feed our obsession with all things gruesome – an obsession that is now an acceptable facet of our society.

Psychopaths aside, perhaps those most commonly associated with the word ‘cannibal’ are the so-called ‘primitive’ social or ethnic groups who historically have engaged in ritual man-eating. In colonial times, these ‘savages’ were at best pegged as souls to be saved, but only if they repented. If they failed to do so, they were brutalised, enslaved and murdered. The most infamous period of such ill treatment began during the last years of the fifteenth century when millions of people indigenous to the Caribbean and Mexico were summarily reclassified as cannibals for reasons that had little to do with people-eating. Instead, it paved the way for them to be robbed, beaten, conquered and slain, all at the whim of their new Spanish masters.

However, although defining someone as a cannibal became an effective way to dehumanise them, it’s also worth remembering that there is evidence of ritual cannibalism, as embodied in various customs related to funerary rites and warfare, occurring throughout history.

As I began studying the subject, I sought to determine not only the perceived function, significance and consequences of cannibalism, but also the extent of the practice, both temporally and geographically. This was complicated by general disagreement among anthropologists: some deny that ritual cannibalism ever occurred, others claim that it was a rare exception and still others assert that it was a relatively common practice in many cultures – including Western society – throughout history and in a variety of forms.

As a zoologist, I was intrigued at the prospect of documenting cases of non-human cannibalism too, and I have made this my starting point in the book. Looking back now, I can see that I’d begun my inquiry with something less than a completely open mind. Part of me reasoned that since cannibalism is an uncommon behaviour in humans, it would likely be similarly rare in the animal kingdom. Once I dug further, though, I discovered that cannibalism is far from unknown in the animal kingdom, although it differs in frequency between major animal groups, being nonexistent in some and widespread in others. It also varies from species to species and even within the same species, depending on local environmental conditions. Animal cannibalism serves a variety of functions, depending on the cannibal. There are even examples it benefits the cannibalised individual.

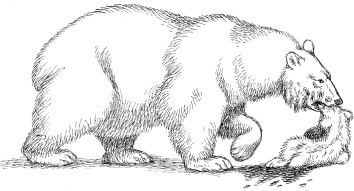

In several instances animal cannibalism appears to have arisen only recently, and largely due to human activity. The false claim that polar bears are now eating their own young owing to climate change and the shrinking of Arctic ice is one high-profile instance of this phenomenon that hasn’t escaped the scrutiny of the press.

The real story behind polar-bear cannibalism turned out to be just as fascinating, though it would also serve as a perfect example of how many stories about cannibalism have turned out to be untrue, unproven or exaggerated – distorted by sensationalism, deception or a lack of scientific knowledge. With the passage of time, these accounts too often become part of the historical record, their errors long forgotten. Part of my job would be to expose those errors.

I was also extremely curious to see if the origin of cannibalism taboos could be traced back to the natural world. Might it be that an aversion to consuming our own kind is hardwired into the human brain and thus part of our genetic blueprint? I reasoned that if such a built-in deterrent existed, then humans and most non-humans (with the exception of a few well-known anomalies such as black widow spiders and praying mantises) would avoid cannibalism at all costs.

Conversely, was it possible that the revulsion most of us feel at the very mention of cannibalism might stem solely from our culture? Of course, this led to even more questions. What are the cultural roots of the cannibalism taboo and how has it become so widespread? I also wondered why, as disgusted as we are at the very thought of cannibalism, we’re so utterly fascinated by it. Might cannibalism have been more common in our ancestors, before societal rules turned it into something abhorrent? I looked for evidence in the fossil record and elsewhere.

Finally, I considered what it would take to break down the biological or cultural constraints that prevent us from eating each other on a regular basis. Could there ever be a future in which human cannibalism becomes commonplace? And, for that matter, is it already becoming a more frequent occurrence? The answers to these questions are far from clear cut but, then again, there is much about the topic of cannibalism that cannot be neatly labelled either black or white. Likely or not, though, the circumstances that might lead to outbreaks of widespread cannibalism even in the present century are grounded in science, not science fiction.

In researching these questions I have looked at the iconic cases of human cannibalism through history alongside animal behaviours, approaching each from a scientific viewpoint, delving into aspects of anthropology, evolution and biology. What, in biological terms, happens to our bodies and minds under starvation conditions? Why are women better equipped to survive starvation than men? And what physiological extremes would compel someone to consume the body of a friend or even a family member?

As you read on, you will encounter everything from cannibalism in utero to placenta-eating mothers who uphold a remarkably rich tradition of medicinal cannibalism. I hope you’ll find this journey as fascinating and surprising as I have – a journey whose goal is to allow us better to understand the complexity of our natural world and the long and often blood-spattered history of our species.

With this in mind, why not grab that big Amarone (or, if you’re more cinematically inclined, a nice Chianti) and let’s get started.2

Footnotes

1 When Psycho opened, on 16 June 1960, it was an instant hit, with long lines outside theatres and broken box office records all over the world. Over fifty years later the film is remembered best for its famous shower scene, one which reportedly caused many of our Greatest Generation to develop some degree of ablutophobia, the fear of bathing (from the Latin abluere, ‘to wash off’). Few theatregoers realized that the ‘blood’ in Psycho was actually the popular chocolate syrup Bosco (a fact the company somehow neglected to mention in their ads and TV commercials).

2 For suitable background music, try ‘Timothy’, the catchy one-hit wonder by The Buoys. The song, written by Rupert Holmes of ‘The Piña Colada Song’ fame, tells the tale of three trapped miners, two of whom survive by eating the title character. In 1971 ‘Timothy’ reached number 17 on the Billboard Top 100 even though many major radio stations refused to play it. In an unsuccessful attempt to reverse the ban, executives at Scepter Records began circulating a rumour that Timothy was actually a mule.