4

The expansion of the domain of the sacred: the emergence of art as an autonomous domain, separate from the profane

In the history of a king, everything lives, everything moves, everything is in action; we only have to follow him, if we can, and carefully study him alone. It is a constant enchantment of marvellous facts, which he himself begins, he himself ends, as clear, as intelligible when they are carried out, as they are impenetrable before they are executed. In a word, one miracle follows closely on another miracle; attention is always intense, admiration always concentrated; and we are not less struck by the grandeur and promptness with which peace is restored than we are by the rapidity with which conquests are made. Happy those who, like you, sir, have the honour to approach this great Prince, and who, having contemplated him with the rest of the world on those important occasions when he controls the destiny of all the earth, can again contemplate him in intimacy, and study him in the smallest actions of his life, no less grand, no less a hero, no less admirable as full of equity, full of humanity, always calm, always master of himself, without inequality, without weakness, and finally the wisest and most perfect of all men!

Jean Racine, ‘Discours prononcé à L’Académie française, à la réception de MM. (Thomas) Corneille et Bergeret’, 2 January 1685

Art is not anecdotally or incidentally related to power. It is structurally and intrinsically linked to hierarchized societies who order the world vertically on a scale which opposes high, sacred and spiritual to low, profane, material and physical. The very categories of ‘art’ and of ‘artist’ are intimately linked to the separation of the sacred and the profane, and, essentially, to the dominant and the dominated. As a result, it is only out of convenience or the careless use of words that we refer to ‘art in primitive societies’, in as much as the practices thus indicated by the external observer have very little to do with what was gradually being invented in Europe, from the Middle Ages to the beginning of the nineteenth century.1 This ethnocentrism, which consists in applying Western categories to essentially foreign realities and in making art, religion or economics into some sort of basic transhistorical element, has been much criticized by anthropologists.

The history of art as a specific area of practice has often been seen as a history of the ‘conquest of autonomy’.2 Artists would therefore, battle after battle, have won their independence in relation to various powers (ecclesiastical, political or economic) and the right to create works without any commission or any specific function. Such an interpretation emphasizes the liberation of artists and their freedom of expression and sees culture as an ‘instrument of freedom presupposing freedom’.3 However, if this interpretation in terms of the autonomization of art is possible, it remains only a partial one.4 For the history of the creation of a relatively autonomous artistic domain is inseparably tied up with the history of the separationsanctification of art, in other words, the history of art as a domain separated from the rest of the world, part of a social relationship of sacred/profane, underpinned by a relation of domination. At the end of this process, the artist takes his or her place alongside the dominant (earthly or spiritual), keeping a distance from the commonplace, enthroned in his demiurgic uniqueness or like a lord above the multitude. Less ‘positive’ or perhaps less ‘glorious’ for artists, such a vision is unavoidable when, instead of tacitly (and sometimes explicitly) rising to the defence of art and artists, we simply describe the reality of the social relationships which structure artistic activities in relation to what is not artistic. The reason the sociologist or the historian spontaneously springs to the defence of the autonomous artist is often because they are projecting their own position as a scholar. The artists’ struggle to gain public recognition and to defend the autonomy of their work somewhat echoes similar struggles in scholarly circles. And this is where the blind spot of many analyses of the world of the arts is to be found.

In order for the ‘material fabrication of the product’ to be ‘transfigured into “creation”’,5 art and the artist must collectively enter into the restricted field of the sacred and cut themselves off from the profane. The ‘demiurgic capability’ of the ‘creator’, which is not just a (metaphorical) way of speaking, like the ‘magic power of transubstantiation with which “the creator” is endowed’, are the products of a long history of power, of the sacred and of collective beliefs with regard to art. If relations of domination did not underpin our societies, if we did not believe in the exceptional value of art, if we did not support the cult of the autograph painting, if we had not, century after century, elevated certain painters to the status of ‘great men’ who are the pride of their nations and a part of their pantheons, there would not be so much interest, attention, passion or emotion around their paintings. All of that is a reminder of the existence of the collective and historical conditions capable of producing an emotion of an aesthetic nature when confronted with a painting.

Some might think that to link beauty or the sublime to the backcloth formed by relations of domination is tantamount to a somewhat crude sociological reductionism. However, far from having only very tenuous links to the question of power, art is in fact truly indissociable from it. Its very definition, with respect to the split between the liberal arts and the mechanical arts, the nature of how it is used and appropriated by society, as well as the way it is viewed (with admiration), all lead back to the relationship between dominant and dominated.

Poets and artists, sovereigns and demiurges

Throughout the long history of State societies, emperors, kings and princes, popes, legislators, poets and artists have successively been regarded as analogous to gods. Art would become a sacred domain, and as such, would be separate from profane and ordinary activities. The process goes back a very long way in history but is particularly visible at the time of the Renaissance, continuing into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the quasi-sanctification of painters and ‘the consecration of the writer’.

In an essay on the ‘sovereignty of the artist’, Kantorowicz showed how the jurists of the Middle Ages, specialists in both Roman law and canon law, contributed to forging the arguments which would be used to distinguish artists from the profane.6 Poets and painters, like sovereigns, were to find themselves compared to God, in the sense that they created things which did not exist. These are not just simple imitators of nature and of the real, but creatores in the fullest sense of the term. Kantorowicz points out that, for a connoisseur of the law in the Middle Ages, it is not very difficult to recognize medieval legal concepts in the theories of Renaissance art: ‘The group of notions such as ars, imitatio, natura, invention, fictio, veritas and divine inspiration is important because it is associated with problems which can be traced back without difficulty to the medieval jurisprudents.’7

First of all, the medieval jurist saw the activity of the legislator as being in the image of God. He asserts that, ‘For by fiction the jurist could create (so to say, from nothing) a legal person, a persona ficta – a corporation for example – and endow it with a truth and a life of its own’.8 By envisaging legislative activity as an activity capable of creating realities which had not previously existed, the jurist ‘commonly idealized as the “animate law”, by his act of re-creating nature (so to say) within his limited orbit, showed some resemblance with the Divine Creator when creating the totality of nature’.9 Now this same idea is also present in artistic theories from the end of the Renaissance period according to which ‘the ingenium – artist or poet – was often recognized as a simile of the creating God, since the artist himself was considered to be a “creator”’.10 Making a poet or a painter an equal of God or a quasi-god, makes art a privileged domain, separated from the profane. The artist becomes a creator comparable to a God, a pope, a king or a legislator. Symbolically he becomes part of the world of the powerful and is clearly positioned on the side of the sacred.

The metaphor of ‘creator’ is an extremely significant one in the Judeo-Christian tradition which, according to Kantorowicz, dates from 1200. In a text dated around 1220, the canonist Tancred writes, for example, in a commentary on a decree issued by Pope Innocent in 1198, that the pope ‘acts as the vice-gerent of God’ for ‘he makes something out of nothing like God’. Acting in lieu of God, he has ‘the plenitude of power in matters pertaining to the Church’ and nobody can judge what he does (‘Nor is there any person who could say to him: Why dost thou act as thou do?’).11 Hostiensis (1200–1271), in his Summa aurea, says of the pope that he ‘makes something that is, not be; and makes something that is not, come into being’; and, towards the end of the century, Guillaume Durand (who died in 1296) mentions this doctrine in his Speculum iuris, defining pontifical power as that which can ‘change the nature of things’.12

These powers that are attributed to the pope are also granted to the highest ranking holders of secular power, to emperors, princes or kings, as well as those who draw up the laws. The same model re-surfaces to describe the poets and painters of the Renaissance period. Kantorowicz explains that this method of transferring portrayals is a common practice with medieval jurists, who draw parallels between very different seeming realities:

we may say, the essence of the art of the jurists, who themselves called this technique aequiparatio, the action of placing on equal terms two or more subjects which at first appeared to have nothing to do with each other. […] That method of ‘equiparation’, however which was not restricted to jurisprudence, can help us to understand in what respects the theories of the jurists might appear to have been relevant to later artistic theories.13

We find, for example, a similar comparison between the poet and the emperor (Caesar) in Dante: ‘Caesar and poet appeared to Dante potentially on one level, since only the “highest political and the highest intellectual principates” could be decorated at all with the laurel.’14 But the ceremony of Petrarch’s coronation in the Capitol, in 1341, turns the discursive metaphor into the reality of the social treatment of the poet. Whether the artist is compared to a god (a little god the creator) or to a sovereign (Dante places the poet on the same level as the emperor and Petrarch is indeed crowned with an imperial laurel wreath), the same matrix is essentially at work, separating and opposing the sacred and the profane, dominators and dominated, auctores from ordinary mortals, creatores from those who are not, etc.

Hans Blumenberg also referred to the theological roots of the figure of the artist: ‘Both the self-conception of the artist and the theoretical interpretation of the artistic process by means borrowed from theology, all the way from creation to inspiration, have been abundantly documented.’15 God is often compared to an artist who creates, which is a way of making the artist an equivalent to God the creator. Thus, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola uses the metaphor of ‘mightiest architect’ to refer to God:

the Mightiest Architect, had already raised, according to the precepts of His hidden wisdom, this world we see, the cosmic dwelling of divinity, a temple most august. He had already adorned the super celestial region with Intelligences, infused the heavenly globes with the life of immortal souls and set the fermenting dung-heap of the inferior world teeming with every form of animal life. But when this work was done, the Divine Artificer still longed for some creature which might comprehend the meaning of so vast an achievement, which might be moved with love at its beauty and smitten with awe at its grandeur. When, consequently, all else had been completed (as both Moses and Timaeus testify), in the very last place, He bethought himself of bringing forth man.16

This comparison of God and the artist also allows the author to imply that, just as divine creations must be admired by humankind, so artistic creations attract the admiring gaze of the profane:

For nothing so surely impels us to the worship of God than the assiduous contemplation of His miracles, and when, by means of this natural magic, we shall have examined these wonders more deeply, we shall more ardently be moved to love and worship Him in his works, until finally we shall be compelled to burst into song: ‘The heavens, all of the earth, is filled with the majesty of your glory’.17

We see therefore the origin of the admiring gaze in the domain of art and its theologico-political foundation: since the artist is made equivalent to God, men must admire artistic creations in the same way they admire those of God.

Yet the traces of such definitions of the poet or painter as ‘creator’ or ‘sovereign’ can be found long before the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, for example in Horace’s reflections on the art of poetry (65–68 BC):

It was finally Horace’s Ars poetica which extended the new and quasisovereign state of the poet to the painter; for the Horatian metaphor ut pictura poesis or rather its inversion ut poesis pictura became the pass-key which eventually opened the latches to the doors of every art – first to that of the painter, then to the arts of the sculptor and architect as well. They all became liberal artists, divinely inspired like the poet, while their crafts appeared no less ‘philosophical’ or even ‘prophetical’ than poetry itself. It was a cascading of capacities, beginning from the abilities and prerogatives conceded ex officio to the incumbent of sovereign office of legislator, spiritual or secular, to the individual and purely human abilities and prerogatives which the poet, and eventually the artist at large, enjoyed ex ingenio.18

If Plato intended to drive poets out of the City, it is because the oral (aèdes) poets he was targeting were not yet the ‘artists’ they would later become. Disseminators of myths which they varied depending on the audiences addressed, he clearly sees them as belonging to the ‘many’ (as opposed to the ‘One’), with the ‘moving’ and the ‘becoming’ (vs the ‘immovable’ and the ‘being’), with ‘doxa’ or ‘opinion’ (vs the ‘Truth’ or the ‘Idea’), with the ‘visible’ (vs the ‘invisible’), with ‘sensibility’ (vs ‘intelligibility’), with ‘mimesis’ (vs ‘reason’), and thus opposes them, point by point to the philosophers.19 Now Plato defines the philosopher as a quasi-god, that is to say as someone who, thanks to new forms of knowledge (written), occupies an elevated and distant position and can contemplate the world from the height of this transcendent position:

The Platonic concept of elevation is a key element of his philosophy. If, for example, we refer to texts which feature these derivatives of ϋψος, we realize that they all touch on the definition of the philosopher. Thus, the presence of ύψóθεν in the Theaetetus allows the characteristics of the philosopher to be defined: he is the one who places himself on high, who sees things from above. The definition of the natural philosopher is made in opposition to the model of the materialistic man, who seeks only his own profit and keeps his eyes fixed on the ground. The idealist, for his part, does not concern himself with gossip, squabbles, with anything associated with the spirit of baseness. He prefers the practice of geometry and astronomy. Whereas the one who lives through his senses is motivated by a perpetual, imperfect and multiple destiny, the philosopher according to Plato, is someone who seeks perfection, eternity, the unity behind the sensible, in order to make himself like the divine, to elevate himself towards him, and to see reality ἁοήο, from above.20

In his research on the vocabulary of Indo-European institutions, Benveniste also discovers the comparison of the poet and god, both using language to make previously non-existent realities exist: ‘The god is singing of the origin of things and by his song the gods are “brought into existence”. A bold metaphor, but one which is consistent with the role of a poet who is himself a god. A poet causes to exist; things come to birth in his song.’21 And we know that, in Indo-European languages, the notion of ‘auctor’ includes all those who, like the gods, are capable of making things with words:

The term auctor is applied to the person who in all walks of life ‘promotes’, takes an initiative, who is the first to start some activity, who founds, who guarantees, and finally who is the ‘author’ […] Every word pronounced with authority determines a change in the world, it creates something. This mysterious quality is what augeo expresses, the power which causes plants to grow and brings a law into existence. That one is the auctor who promotes, and he alone is endowed with the quality which in Indic is called ojah. We can now see that ‘to increase’ is a secondary and weakened sense of augeo. Obscure and potent values reside in this autoritas, this gift which is reserved to a handful of men who can cause something to come into being and literally ‘to bring into existence’.22

We find here, therefore, the premises of what Kantorowicz observes in the Middle Ages. The act of bringing together gods, kings, popes, legislators, poets and artists, or more precisely, of thinking of them as kinds of quasigods because of their capacity to engender new things, places them at once alongside the sacred and the venerable (uenerandus) and they are raised above common mortals:

a person becomes sanctus who is invested with divine favour and so receives a quality which raises him above the generality of men. His power makes him into an intermediary between man and god. Sanctus is applied to those who are dead (the heroes), to poets (vates), to priests and to the places they inhabit. The epithet is even applied to the god himself, deus sanctus, to the oracles, and to men endowed with authority. This is how sanctus gradually came to be little more than the equivalent of venerandus. This is the final stage of the evolution: sanctus is the term denoting a superhuman virtue.23

Other texts show that, long before the Renaissance, an author like Macrobius (Flavius Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius), born around 370 AD, portrayed the poet Virgil as a creator: ‘Macrobius established a very strong link between the Virgilian style and nature which prefigured an even more important analogy, that of the poet and the divine creator, as terms such as “comparavi” and “similitudinem” clearly demonstrate. The poetic work is thus conceived as a microcosm in the image of the macrocosm created by God, reproducing its variety and harmony on a human scale (in musica Concordia dissonorum).’24 What these reflections on the part of Macrobius set out to do is to show that Virgil is not just a mere imitator, simply reproducing nature, but indeed an inventor in the same position as God:

The poet is not simply content to imitate nature, he recreates it and it is nature reconstructed from what he himself knows about it, from his experience and his reading, his recollections, in order to pay homage to prestigious models. Thus, far from being considered a simple imitator, the poet according to Macrobius possesses a freedom of action which places him more on the side of invention, of creation. Compared to nature, the poem as a microcosm makes its author a creator akin to God for the macrocosm. The poet is not only inspired by the divinity for whom he acts as the cantor, his work rivals the Creation. Curtius identified this originality in Macrobius, the first author to consider the poet as a creator and his work as a creation. The idea was already implied in Longinus and Plotinus, but remained implicit with these writers. Macrobius seems to be an exception because he is the only writer in Antiquity to show the analogy between the poetic oeuvre and the macrocosm.25

The conception of the poet-creator did not, however, gain strength or become more widespread until much later, in the fifteenth century. With Georges of Trébizond (De suavitate dicendi ad H. Bragadenum, Venice, 1429), for example, it is no longer a single isolated poet, but all poets who will be considered as artists. Other writers would speak of Ronsard (considered as the ‘divine genius’ of poetry) in the same way Macrobius spoke of Virgil. And Jules César Scaliger (1484–1558) in his Poetics (Poetices libri septem, 1561), makes the poet into a sort of demiurge, who is to the ear what the painter is to the eye:

At the beginning of his Poetics, Scaliger defines the poet as another God (alter deus) and his creation as ‘another nature’ (altera natura): ‘Only poetry embraces all the arts, and it surpasses them all the more because (as we said) the others reproduce the things themselves, as they are, as though with a sort of sound painting, but the poet creates a second nature, and also a very great number of destinies: in this place he himself becomes in the same way a second god. In fact, what the creator of all things creates, the other sciences represent as though they were merely taking part in things, but since poetry confers an appearance to what does not exist, and adorns what does exist, it seems really to create the things themselves, like a second god, and not to recount them as in a mime, as is the case with the other arts.’ Poetry embellishes what it imitates, it adds the finishing touches to nature which is its model: the imitation is not faithful, it is a recreation, and this fully bestows on the poet the status of demiurge.26

The ‘consecration of the writer’ emerged as a phenomenon in France from around 1760 onwards27 and the cult of the artist (painters in particular) would develop in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. More generally, in societies that were becoming more secular and where religion was increasingly marginalized, the State power no longer needed to be legitimized by a God and did not seek to interpret the world as the writing of the gods. On the contrary, there was a growing realization that an entirely human action (writing) could be superimposed on society (the blank page) in the form of political, legal, scientific and pedagogical writings which were deployed throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: ‘This bourgeoisie-god makes the world (its reason is the capacity to “produce”), and, in the same movement, it dissociates itself from the masses or the “common” class which in myth or symbol receives the world as a meaning.’28 From now on, the role of God would be played by the State which has both the means and the ambition to do so. ‘God’ is replaced by ‘Reason’, the transcendent is replaced by the inherent which nevertheless goes beyond regional and local particularities and contributes to the work of social and cultural homogenization: a politics of language and of education, the codification of laws.

In less than ten years, the activity of the codification of laws proved to be intense: following on from the Civil Code (1804) came the Code of Civil Procedure (1806), then the Commercial Code (1807), the Criminal Code (1810) and the Code of Criminal Procedure (1811). Apart from the fact that this is constitutive of a legal, depersonalized form of domination, based on ‘Reason’, this codification also implies a strong awareness of political action. The codes represent the law for a people who are aware that the power represented by the codes comes uniquely from themselves. The Code represents the active and conscious writing of society through the State and not the word of a god or the sacred text. It puts the rules of communal living within the hands of the people (and essentially of individuals linked to the State). The laws are impersonal and therefore transcend even those who apply them, but they are perceived as of purely human origin.29

From this point on, culture is firmly held in a relationship with a (popular) ‘nature’ thanks to the transformation of the principle of religious distinction between ‘divine’ and ‘human’ to a fundamental principle of distinction between ‘civilization’ and ‘savagery’, ‘cultured’ and ‘ignorant’.30 In an interview with Robert Chartier, Bourdieu could therefore explain this cultural religiosity which is neither metaphorical nor anecdotal: ‘I think that culture in our societies is a sacred site: the religion of culture has become, for certain social categories including intellectuals, the site of their deepest convictions and commitments.’31 Continuing its process of emancipation from the boundaries of the Ancien Régime, the State still continues to separate the sacred from the profane. The introduction of ‘great’ individuals (statesmen, great artists, great scholars, great writers etc.) who can be associated with the nation (with the nation-State) is therefore an element of its policy.

The relatively recent history of the consecration of writers and artists should not, however, allow us to forget that these processes of sanctification are indeed linked to the original position of Mesopotamian and Egyptian scribes, masters of the written form of myths and rites, writing the ‘laws’ and practising the arts of divination which were part of the first temporal and spiritual powers and clearly separated from the profane world. Right up to the portrayals and treatment of contemporary writers, we find traces of this equivalence of the poet and God that Kantorowicz identified in Renaissance theories of art, but which had already been expressed long before then by various other writers. Writing as a solo activity and which consists in creating its own universe from the start to the finish, with its own style, is embraced by many writers who often compare the situation of the author to that of a god, a demiurge, an absolute creator who determines everything and is ‘in command of the ship’.32 And we are no more surprised by the fact that, in the standardized universe of ‘industrial products of fiction’ where a multitude of screen writers work on the scripts of TV series or soap operas, the ‘code which defines the characteristics of the heroes of a series and establishes the rules which must be repeatedly applied’ and which is written by an ‘author’ is called the ‘bible’.33 Even if it is a very long way from the mode of the writer’s solitary activity, the production system of collective writing still retains the dominant, sovereign and transcendent role of the ‘auctor’.

The history of a collective sanctification

It was in the first part of the fourteenth century that Dante, in his Divine Comedy, first used the word ‘artista’. But, between the first occurrence of the word in a modern sense and its consolidation as a socially recognized category, several centuries would elapse. A simple historical consideration of the word ‘artist’ in the French language indeed shows that this generic category was not commonly used in the sense we give it today until the second half of the eighteenth century: ‘The word “artist” in the modern sense, appeared, as a substantive used for the painter, in the second half of the XVIIIth century (Dictionnaire portative des beaux-arts de Lacombe, 1759). The Royal Declaration of 15 March 1777 (“We desire the arts of painting and sculpture to be perfectly equivalent to Literature, the Sciences and other liberal arts”) marks the end of a long evolution.’34 In 1762, the word appeared for the first time in the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, which defined it as someone ‘who works in an art where genius and the hand must converge’.35 It had indeed entailed a long process, involving the sanctification and autonomization of art and of artists, a long history of the separation of art both in relation to the profane and also in relation to the religious notion of the sacred – most of which had been centred on Renaissance Italy – before the situation of an artist both set apart from the world of artisanal (or industrial) production and possessing his own powers of enchantment, independent of all kinds of religious ritual function, would be established. The actors of the world of art still stand today on the pedestal of that history. More often than not, they are not even aware that they are benefiting from the struggles of those who demanded and obtained the sanctification of painting and other arts.

From the fifth century onwards, in Europe, the perception of knowledge and the arts would be strongly marked by an opposition between the liberal arts (made of the trivium ‘grammar-rhetoric-dialectic’ and the quadrivium ‘arithmetic-music-geometry-astronomy’), the most noble arts taught in faculties of art, and the mechanical arts, practised within guilds and whose name quite clearly evokes a manual practice without soul or spirit.36 Within the series of oppositions which structure the perception of hierarchized societies, the high is to the low what spirit is to matter. The collective issue for painters or sculptors, as well as the individual issue for each artist, is to be collectively associated with, or to individually strive towards, the hallowed goal. From the end of the Middle Ages to the Renaissance ‘there is a rupture between art on one side, and craftsmanship and commerce on the other’.37 In order to differentiate himself from the craftsman, the artist was to emphasize the intellectual activity involved rather than the manual work or dexterity. Those who argued in favour of painting and sculpture being integrated into the liberal arts consequently put more emphasis on all the knowledge implied in these activities (geometry, anatomy, history, etc.). In the ‘great chain of being’, painters and sculptors were to occupy positions which were clearly superior to those of simple craftsmen or common workmen.38

In Italy, at the end of the fifteenth century, painters, sculptors and architects were already successfully imposing themselves as practitioners of the liberal arts and were abandoning the profane and no longer valued territory of the mechanical arts. But it was not until the creation in France of the Royal Academy of painting and sculpture in 1648 that there were definitive signs of the ‘shift of painting and sculpture – which were practised within the corporate framework of guilds – to the rank of “liberal arts”’.39 In spite of this collective promotion of art and artists, it was a long time before painters and sculptors were able to benefit from the creative autonomy of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists, working on commissions from individuals (nobles or bourgeois) or from institutions (royal or ecclesiastical). The contractual conditions of the commissions often determined formats, subjects, colours used, timescales for completion, price, etc., which often placed artists in a relationship of considerable dependency.40 Artists only gradually freed themselves from this link of direct dependence, and only with the advent of a genuine art market did the potential buyers of their works cease to have any direct role in the process of creation.

In his magnificent book, the art historian Édouard Pommier studied how, in the course of the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, particularly in Italy (Florence and Rome acting as veritable social laboratories) and then throughout Europe, art, and especially painting, became a prestigious domain, worthy of being conserved, protected, exhibited and contemplated, discussed and commented on.41 Art history, as a learned discourse which takes as its object commentaries and commendations of artists, began with the famous Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects by Giorgio Vasari, published in Florence in 1550, then republished in 1565.42 Thanks to Vasari, the legitimate discourse on art was immediately secured, focusing on the ‘singularity of artists’43 (Michelangelo and Raphael are ‘unique’) and thus eclipsing the collective conditions of the production of a work, its value and the belief in art. As soon as painting and sculpture had become liberal arts, distinct from mechanical arts, the process of regarding artists as remarkable became inevitable. Creators of things which did not exist, comparable to God, they could only be seen as beings detached from all external influence: geniuses, divine or exceptional beings, as opposed to common craftsmen or manufacturers, through the collective magic of the separation of sacred and profane.

The practice of signing the canvas itself accompanied this movement. If the signature was not unknown in the tradition of craftsmanship (as demonstrated by the practices of gold- and silversmiths in the fifteenth century) and represented a fairly common practice amongst engravers from the fifteenth century onwards, it now played a different role and took on a different meaning in the context of a liberal art where the name of the artist had become an indispensable element in the social magic of images:

The Renaissance saw a concentration of studies on the signature in painting. This period in effect marked a deep-seated change: previously carved into the frame or at the margins of the image, the signature was from now on incorporated within the painting itself. This change reveals the changing status of the image: previously in the same category as an icon, an image to sacred virtue which permitted no trace of expression, the painted image became a work of art likely to carry an indication of its provenance. At the same time this change in the status of the image was taking place, the signature revealed the individualization of certain Renaissance artists. […] The practice of the signature was not therefore an isolated phenomenon: it was part of the long history of the emergence of the singular figure of the artist and appeared at the same moment as the first artists’ biographies by Giorgio Vasari and Karel Van Mander, published respectively in 1550 and in 1604. It was in fact an indication of the social status of the artist and of the liberalization of the status of painting, as demonstrated by the emergence of the idea of ‘genius’ and the appearance of a new intellectual configuration, that of the Fine Arts. As early as the Renaissance, certain artists became aware of the graphic possibilities opened up by the signature and chose to sign their works by using their first names (Titian, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, etc.). Around 1633, when Rembrandt Van Rijn decided to use his first name as a signature, he became part of this tradition and made use of this signature to promote his ‘aura of individuality’.44

Vasari’s most important work is, however, preceded by other important texts. Thus, as early as 1390, Filippo Villani wrote a text entitled On the origins of the City of Florence and her famous citizens, where painters appeared alongside poets, musicians or soldiers; in the same year Cennino Cennini composed his Libro dell’arte, which is a hymn to ‘art’ in the sense of the modern meaning of the term ‘fine arts’; then, in 1435, Alberti published his De Pictura, in which he defines the artist as a scholar, a learned figure who masters the sciences as well as history and literature; also, around 1450, Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Commentari linking Italian art to Antiquity; and finally, in 1475, Vie de Filippo Brenelleschi, the first biography of an artist by the mathematician and astronomer Antonio di Tuccio Manetti. The history of the invention of art and of artists thus gradually took shape with texts (by scholars, poets, artists and even non-specialists), which recounted the lives of painters, commented on or interpreted artists’ work, etc., legal measures (which determined the future of works of art and their conditions of circulation), images (artists appeared in pictures or on medals, were represented in portraits, self-portraits or statues, etc.), monuments and institutions (such as the Academy in the second half of the sixteenth century, or museums which would not develop in Europe until the end of the seventeenth century and particularly in the eighteenth century), and ritual practices (such as, towards the beginning of the sixteenth century, artists embarking on ‘art tours’ to admire the ‘masterpieces’ which were to be found primarily in Rome or Florence. They would copy these, drawing inspiration from them and aspiring to better them.) All the various elements of this history have contributed to transforming artists into individuals worthy of being idealized and set apart from common mortals, and to turning their works into creations worthy of being protected, contemplated and admired.

In the course of this process of artists being accorded increasing respect, art was itself used as an instrument of legitimacy and glorification for both political and religious powers. It was used to attract attention, to focus the gaze, to demonstrate power or nobility. The situation worked both ways: people valued art only because it was capable in return of supplying legitimacy where there were competition and power struggles between families, municipalities, nations or religious powers. Thus the painter, sculptor and architect Giotto (1267–1337) would be consecrated as ‘illustrious’, notably by the writer Boccaccio (1313–1375), insofar as he had participated in the construction of the grandeur and glory of Florence (the city had put him in charge of the construction project for the cathedral bell-tower). ‘In the last decades of the quattrocento, it becomes clear that the arts have become a fundamental element in the identity of Florence and that artists are definitively admitted to the ranks of illustrious men, who deserve to be remembered by a history which is inseparable from fame.’45 This singling out of artists was by no means in opposition to national reasoning. Indeed, the identification of certain ‘great names’ meant that the State, the nation could take pride in counting such geniuses amongst their citizens.

If we take the Aufklärung as just one emblematic example, Riedel, curator of the Dresden Gallery, was already expressing just such an intention in his first catalogue (1765): ‘These treasures perpetuate the memory of all these artists who distinguished themselves by their genius and their talent. But, by conserving monuments of art, they shape at the same time the taste of the nation.’ These perspectives feed a new cult of the masterpiece and of the signature of the master.46

International struggles to appropriate either symbolically or in reality artists or their best known works (Was Poussin French or Italian? Was Picasso Spanish or French?), are not dissimilar to the strategies of major European football clubs in associating themselves with the most famous footballers.

However, in order for painting to be able to produce such effects, it needed to be accepted as part of a liberal and noble art rather than a mechanical art associated with manual activity. Clearly, in order to gain legitimacy, painting or sculpture must be placed in the same category as the mind, the intellect, learning and, finally, the divine.47 If the divine nature of the artist is suggested in Dante,

it would be more than a century later that the talent of an artist would be publicly qualified as ‘divine’, and even longer before Leonardo da Vinci […] demonstrated the superiority of painting: ‘Therefore, we rightly call painting the grandchild of nature and related to god.’ Elsewhere he speaks of the ‘divine science’ of painting, and of the ‘divine character of painting’, which means that ‘the spirit of the painter is transformed into an image of the spirit of God’.48

Everything has therefore been done to demonstrate that painters or sculptors are only putting into practice ideas or conceptions, that they are above all scholars, creators, learned individuals or poets and that without inspiration, and without knowledge or soul, they would be incapable of creating the work produced. From 1440 especially, painting was legitimized by being compared to other long since legitimized arts (such as poetry or ancient sculpture), and by being referred to in terms which contribute to making it sacred, elevating it from its status as a mechanical art.49

In a dialogue entitled Anuli, Alberti associates the eye with God. Through his eye, the artist occupies the same position as a king or a God:

‘There is nothing more powerful, swift or worthy than the eye, it is the foremost of the body’s members, a sort of king or god. Why did the Ancients consider God as being like the eye, who surveys all things and reckons them singly? We are enjoined to give glory for all things to God and to consider him as an ever present witness to all our thoughts and deeds […]’ Praise for the eye therefore which goes much further than the timid utterances of Cennini and anticipates the words of Leonardo da Vinci: the human eye, taken as an image of the omniscience of God and of his omnipresence, but also an image of the power of the human spirit, affirmed with a proud assurance, with respect of the divine all-powerful in which are associated humanly contradictory effects of visual acuity and swiftness of movement. Man, the humanist and the artist, assigns to himself the divine power, which will be officially attributed to Brunelleschi some years later […] But it is also the eye of the artist which is exalted: the role of sight in knowledge, the importance of the gaze of the artist, compared to the gaze of God who sees and who judges.50

In his De Pictura, Alberti makes the eye the ‘symbol of the divine power of man over nature’ and reveals the ‘impressive height of his cultural ambition’.51 Artists thus demonstrate their confidence in themselves, their sense that they are beings comparable to gods and their conception of their art as an activity which is both intellectual and noble.

It was also between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance that the practice of collecting art began to take shape, initially in the form of private52 collections but quite quickly expanding to public ones which, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, would result in the invention of the modern museum as a public space for collections of works belonging to the national community and exhibited for all to see. A gallery in the Luxembourg Palace was opened to the public in 1750, the British Museum in London welcomed its first visitors in 1759, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence in 1765, the Louvre in 1793 and the Prado in Madrid in 1819, etc. And, as we shall see, the museum is the symbolic place which marks the separation of the sacred and the profane and which paves the way for a relationship between admirable works and an admiring public.

And, of course, if works are to be admired, the public needs to be prepared to admire them. As Pommier writes: ‘Artistic culture is part of the culture of the perfect gentleman and develops in him the pleasure (piacere) he gets from the spectacle of the world.’53 The eye develops through frequent contact with the works themselves and with books and writings about the arts, with many references to the art of Antiquity. Far from being the models of the objective history of artistic phenomena, the first texts to come under a protohistory of art very actively endorse the process of the sanctification of art, by praising the genius of great artists and providing aesthetic categories which allow the spectators to contemplate, judge and evaluate the different works:

The comments made by Vasari, Dolce, Armenini therefore combine to prove to us that a ‘public’ now exists; and that this public, made up of ‘connoisseurs’ and of ‘amateurs’ is no longer content to contemplate images of faith or historical depictions, but looks at works of art and wants to be able to appreciate them, in other words, to analyse and compare them, thanks to knowledge, ‘the true reason’ which refers back to history and theory […] Art has invented for itself a public and this explains the success of Vasari’s book. […] To this public, the Lives, the treaties of Pino and of Dolce, of Lomazzo and of Armenini, to mention only the most important, bring a code of analysis which allows them to look at works of art, to experience them more deeply and to be able to discuss them coherently and the rules of such a code are more or less fixed for the next three centuries.54

From relics to works of art

It may be […] that, for a very distant posterity, the cult of saints and that of great artists will not be two very different things, in one or the other case, they are individuals who are outstanding and superior within the social hierarchy.

Valéry Larbaud, Lettre d’Italie [1924], Allia, Paris, 1996, p. 52

Resorting to religious metaphor in order to speak about culture or comparing it explicitly to religion (‘cultural salvation’, ‘cultural grace’, ‘religion of art’, ‘holy places of art’, ‘sanctification of art and of culture’, ‘worship of art’, ‘temples of culture’, etc.) has been a relatively common practice since the nineteenth century. In European societies affected by the Enlightenment, using the vocabulary of religion to refer to a social phenomenon which is not spontaneously seen as religious is a way of distancing the object in question and of adding a critical, denunciatory tone to the discourse.

Thus, in his Letters to Miranda and Canova on the Abduction of Antiquities from Rome and Athens, the French archaeologist, philosopher and art critic Quatremère de Quincy, who champions the idea that art works (in this case, Italian ones) should remain in their country of origin, compares the attitude to works of art of those seeking to transfer Italian masterpieces to France with that of those who once sought to obtain holy relics at any price. In this way, he criticizes a new form of idolatry:

But this Raphael, whose pictures are so highly coveted, more through superstition and vanity than through taste or love of beauty, how few know the value of his works, and the value of his genius! All collections want to have one of his pieces, genuine or false, just as in the past, all churches wanted to have a fragment of the true cross. The misfortune is that the virtue attached to the whole of a school is not, as in the case of the relic, contained within each piece broken off from that school.55

The comparison (historically very pertinent) with the relics of a not so distant past only, however, applies to the ‘poor uses’ of works of art, to the superstitious and idolatrous usages from days gone by, and fails to see that the sanctification of art is also, and especially, in the cult of beauty and of artistic genius which is not challenged.

During this same period, Goethe writes a description of the museum in Dresden which emphasizes its likeness to the church. The same refined décor, the same respectful silence, the same atmosphere of reverence, art is a form of the sacred without god:

This room, turned in on itself, this luxury, this refinement; the recently gilded frames, the polished floor; this profound silence, all of this combined to create a solemn impression, unique in character, reminiscent of the emotion with which one entered the house of God; this emotion deepened still further at the sight of the master-pieces on show, genuine objects of veneration in a temple consecrated to the cult of art.56

Almost two centuries later, in 1968, the artist Jean Dubuffet makes a clear comparison between culture and religion, denouncing class privileges and the artists’ role in legitimizing power:

Culture tends to take the place formerly occupied by religion. Like religion, it now has its priests, its prophets, its saints, and its colleges of dignitaries. The conqueror who seeks consecration presents himself to the people no longer flanked by the bishop, but by the Nobel prize. To be absolved, the unjust lord no longer founds an abbey, but a museum. It is now in the name of culture that we are mobilized, that we preach crusades. It has come to play the role of ‘opiate of the people’.57

And it is with the same critical intentions, although in a less polemical and more academic form, that, in the same era, Bourdieu would use religious language in his work on culture:

Objectively speaking, at the moment, the museum is basically a sacred place just like a church. It is perhaps the church of modern times. Or at least it is perhaps the church of certain social classes in our society, that is to say a place where we can be in the presence of sacred things and where we go to be made sacred by being in the presence of sacred things. And I would even go as far as to say, it is a place where we go to become sacred, to be sanctified, leaving the profane outside the door, in other words, setting ourselves apart from the profane. That is perhaps its most important role. If the cult of the museum fills such a role in our society for certain social classes, it is perhaps essentially because its role is to set apart, to separate. Since it separates those who are able to enter the museum from those who are not able to enter.58

However, by using the metaphor in this way, we are preventing ourselves from seeing the truly sacred nature of art and culture and from understanding that all power engenders its own forms of separation between the sacred and the profane. A universal mechanism which underpins all known human societies, the separation of the sacred from the profane, closely linked to relations of domination, should be recognized and studied as such rather than abandoned in a latent, implicit state within religious metaphors. We need to move on from a simple analogical displacement, which means that we refer to the world of art as though it were a religious world, while at the same time believing that it is fundamentally not so at all, to the historical interpretation of art as a sacred domain. By doing so we discover that all our societies, which claim to have lost touch with the sacred and to be disenchanted and rationalized, are indeed fundamentally sacred. Finally, a superficially religious reading also prevents us from going further back to religious practices which are in fact extremely close to those involving placing works of art in museums to be admired, namely, the exhibiting of holy relics in European churches from the Middle Ages onwards.59

Peter Brown pointed out that it was towards the end of the fourth century that the holy man, a sort of living icon, appeared in Europe as a ubiquitous figure of power,60 believed to be in possession of supernatural power. The Christian church organized around its saints, their tombs and their relics a whole sacred world which attracted believers like a magnet attracts iron filings. And, of course, each town sought to be part of the great symbolic competition by claiming to possess the ‘remains’ of some saint or other, of greater or lesser renown, so as to attract visitors and enjoy the attendant prestige.61 If Eastern Christianity had little control over the production of its ‘saints’ (Brown refers to a ‘disastrous overproduction of the holy’), Western Christianity, on the other hand, restricted the processes of sanctification notably by generally waiting until people had died before beginning to sanctify them by producing their hagiographies. Gregory of Tours (539–594), bishop of Tours and church historian, was ‘oppressed by how infinitely small the number of such tombs must be’.62

By limiting the number of sacred places and objects, the Church was thus ensuring it could maintain its distinctive force. The more saints there were to worship, the more the relative force of each of them was diminished. The aim was to obtain reverentia towards all that is sacred, reverentia as opposed to rusticitas (a word which refers to the behaviour of peasants, but the best translation of which is, according to Brown, ‘boorishness’, ‘slipshodness’63). The rusticitas results from an ignorance about the sacred character of things. Those who are incapable of recognizing the sacred character of relics can only behave boorishly towards them, with no sense of the respect or of the veneration that becomes such objects. Rusticitas was therefore ‘the failure, or the positive refusal to give life structure in relations with specific supernatural landmarks.’64 For a place or an object to be recognized as a sacred place or object, required a specific set of circumstance: that people with authority (at the least an ordained priest) should bless it in order to sanctify it, that similarly authorized people should conserve and look after it so as to distinguish it from profane places or objects and, last but not least, that the faithful be taught to recognize it as a sacred place or object, with appropriate attitudes and behaviour, for, as Brown says, ‘A relic that is not acclaimed is, candidly, not a relic’.65

The processes of limitation, of control, appropriation, recognition or non-recognition of relics clearly shows that this is a matter of symbolic power. Whoever possessed these objects and had control over them, whoever had the power to transform ordinary objects into sacred relics and was in charge of their movements and whereabouts, would have power over all those disposed to believe in the sacred nature of the so-called relics. For the reverentia towards such objects was merely a roundabout way, for those who control them, to obtain reverentia for themselves. A roundabout way perhaps, but a politically subtle one in that it could contribute towards stabilizing the phenomena of ‘reputation’ or of ‘recognition’, which could be fragile when institutions were sometimes weak or precarious. As Brown writes, ‘Gossip is a constant factor in the life of the sixth-century church. It is a factor which we should take very seriously in the attempts of the bishops to establish their status in society. […] Hence, perhaps, the importance for such men of the cult of the saints. They, at least were secure. They had passed the test of time.’66

By welcoming relics to a town, the beliefs of the community are harnessed, the members of the community are drawn closer together and the power of the administrator and manager of these sacred objects is firmly established. Relics are instruments of power, the means of consolidating a group and of establishing and maintaining a dominant position within the group:

The fragility of the consensus surrounding the bishop brings us to our last question: apart from general excitement, what is the specific message of the ceremonial of the saint’s festival in Gaul in the sixth century? I think we can be clear – it is a ceremony of adventus and consensus. The saint arrives at a shrine, and this arrival is the occasion for the community to show itself as a united whole, embracing its otherwise conflicting parts, in welcoming him. The same ceremonial is as valid for the great regular festivals as for the arrival of a new relic.67

The bishops thus strengthen their power by keeping their hold on the objects, the relics, which are the ‘depository of the objectified values of the group’.68

Krzysztof Pomian pointed out the ‘policy of capitalization of the sacred in the form of relics and holy images’69 favoured by the Venetian governments from the thirteenth century onwards in the context of the cult of Saint Mark. From diverse and varied relics and treasures to commissions for works of art (mosaics, reliquaries, sculptures, paintings), to the products of classical art (also a source of dispute between Genoa and Florence), everything was put in place to draw the attention of powerful people to the town and to put it firmly on the map. By the same token, the goal was thus to reinforce the ‘splendour’, the ‘reputation’ and the ‘glory’ of Venice. On the subject of relics, Pomian observes that, between the fourteenth and the sixteenth centuries, ‘visitors did not fail to admire them, to worship them and to talk about them even after they had returned to their own countries’.70 But the process of sanctification which was simultaneously occurring in the art world meant that from the fifteenth century onwards, works of art (notably painting and sculpture) would gradually take the place of tens of thousands of relics. In the eighteenth century, Art, which had by then imposed itself as a completely separate domain of the sacred, had supplanted relics in the cultural policy of the town:

But if we now rejoice in the fact that strangers come to Venice to admire the paintings – and not, as in the past, to worship the relics – it is also because, in Venice as elsewhere in Europe, there is amongst the elite, a sort of anthropocentric religiosity which sees in Art – with a capital ‘A’ – the favoured expression of the creative power of man and which places works of art at the summit of the hierarchy of human production, conferring on them a higher status than ever before.71

But which objects can attain the rank of ‘relics’ and which objects can become sacred? Struggles for the definition of what could be rendered sacred and what could be sanctified are obviously a key element in the history of religions. Amongst the most debated objects, we also found icons (images representing religious figures) which play exactly the same role as that long filled by holy men.72 Iconodules and iconoclasts were at loggerheads, the former defending the sacred nature of icons by evoking either their divine origin or the association between the object and holy people from the past. But the latter considered, on the contrary, that icons had been smuggled into the domain of the sacred whereas they were in fact purely profane objects:

It appeared to the iconoclasts that icons had, at a relatively recent time, sidled over the firmly-demarcated frontier separating the holy from the profane. The iconoclast bishops […] meant to put them firmly back in their place […] No prayer of any priest had blessed the icon, so that, through such consecration, it passes beyond ordinary matter to become a holy thing, but it remains common and without honour, just as it leaves the hands of the painter. Icons could not be holy because they had received no consecration from above. They had received only an illegitimate consecration from below.73

The difference of opinion between iconoclasts and iconodules had a clearly political dimension, in the sense that it affected the organization of the power of the Church. The iconoclasts belonged to those who sought to limit the number of sacred objects in order to be able to maintain central control over a small number of objects and, as a result, they were opposed to those more in favour of dissemination who sought a wider distribution of many smaller pieces of the sacred, and, by the same token, were anxious to avoid the monopoly of a minority over a restricted and centralized sacred. For the former, ‘Iconodule superstition was simply a haemorrhage of the holy from these great symbols into a hundred little paintings. Iconoclasm, therefore, is a centripetal reaction: it asserts the unique value of a few central symbols of the Christian community that enjoyed consecration from above against the centrifugal tendencies of the piety that had spread the charge of the holy onto a multiplicity of unconsecrated objects.’74 A strong and centralized system of government versus a multiplication of small scattered powers which are difficult for the Church to control (Brown speaks of ‘Iconoclastic Jacobinism’ which ‘ruthlessly sacked local cult-sites’75). All of this sums up the tensions which developed around relics and icons. The sacred and power clearly emerge as two sides of the same coin.

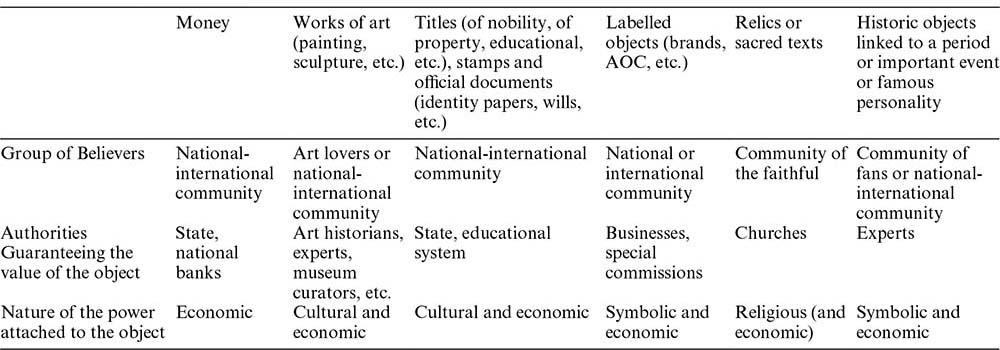

Religious images thus received marks of respect, and even of veneration, just as imperial images once had.76 And when the image was separated from its religious or political context to become an artistic image, it would, in its turn, receive the same signs of deference, tinged with admiration for the artistic creation involved. As a result, the sacred fragmented and took specific forms depending on whether it was political, truly religious or artistic, but always with the same separation between the sacred and the profane and opposing different types of dominators and dominated (the emperor or the monarch and their subjects, God and religious authorities and the faithful, art and its admirers). The sacred could not therefore be confined to the religious. It is always this separation of the sacred and the profane which leads to certain objects, either those which epitomized the group values or those onto which it projected its beliefs, being withdrawn from everyday social life and placed in churches, temples, palaces, studios, galleries or museums. From the private collections of rich patricians or princely palaces to museums, what did change, however, was the opening up to the public so that instead of an activity largely confined to the great Italian or European families, art was now exhibited for everyone to see.

In these forms of the political, religious or artistic sacred, we can indeed see the effects of the transfer of sacred status, or at least of mutual borrowings of the languages of the sacred. We have already seen how the Church managed to borrow from imperial power certain forms of ceremony and types of discourse, just as temporal powers drew on theology and religious language in order to formulate and put into action their own way of exercising power, and poets and artists had also made use of the language of sovereignty or of god the creator. But essentially such borrowing and sharing happen only because similar problems present themselves and because relatively unchanging structures of domination underpin social relationships. Such borrowings are all the easier in that the words used correspond particularly well to the objective situation of the different groups or actors concerned.

It would be a mistake to see relics and icons as sacred objects which would gradually give way to purely human objects with no trace of the sacred. The religious form of the sacred did not gradually disappear in order to be replaced by another form of the sacred. Objects of art were just as clearly separated from the profane in specific places, just as much worshipped and admired as religious objects, and equally capable of weaving the same kinds of enchanting relationships around themselves. Such objects, it is true, no longer link back to a transcendent god, but they are as a result no less fascinating, coveted and appropriated by all the powers (sacerdotal as well as temporal) in their need to harness beliefs to their own advantage. The frontier is no longer drawn between the invisible transcendent and the visible present, but instead, it separates one group of individuals (the creators) from another group. As Olivier Christin writes:

from many perspectives, the quarrel of images and iconoclasm does indeed result in a double movement of desanctification and displacement of images: uprooted from their proper place, deprived of their function, their legitimacy and their original public, certain images only escape disappearing altogether by immediately transforming themselves into works of art, in other words, by taking on a new sacred aura. This transfiguration, this re-sanctifying of the image is only made possible because of the emergence of art collecting, contemporary with iconoclasm and sometimes intimately linked to it. In a collection, a work of art is a religion which has no connection, or very little, to Christianity. It earns its place there simply on the basis of its formal qualities and the fame of the artist. From now on, it is only subject to judgements founded on the idea of artistic autonomy and which are forged within the group of those who define themselves as connoisseurs. The value of a work is assessed according to the complexity of the chosen subject, the sources, the inspiration it draws on, the originality of the workmanship, the skill of the person or people producing, its rarity, and no longer depends on the status of the people represented, the cost of the materials used in its composition, the role it was intended to fulfil. In the modern collection therefore, the outstanding work above all represents a discourse on art, on the collection, on the art of judging art. It is an expression of Beauty and an opportunity for spectators to exert their capacity to judge Beauty accurately.77

One shared property of relics and of works of art lies in the fact that they are only what they are, that they produce only the effects they produce, and have only the value they have in so far as they are associated to exceptional individuals. In the case of relics, these must be the body parts of a holy man or objects which have been in contact with him (scraps of clothing, handkerchiefs, personal objects) and in the case of works of art, it is generally accepted that only works created by a known artist can aspire to the rank of major works. In both cases, and even in other similar ones (the secular relics of famous people such as Napoleon’s hat or the dress worn by Marilyn Monroe), the issue of the authenticity of the objects in question must therefore be addressed. Nothing very easily distinguishes an ancient object from a particular era from another similar one since the fragments of bones or scraps of fabric in circulation do not inherently carry the material proof of their link with the holy person. Certain contemporary copies can sometimes compete with autograph paintings to an extent that can even confuse the finest connoisseurs.

Two main types of beliefs are intertwined in the relationship with these objects: on the one hand, the belief in the sacred nature of the relics or the works of art and, on the other hand, if this is established, the belief in the authentic nature of the particular objects in question.78 Extremely complex controversies as to the authenticity of the objects in question, or the means used to authenticate these objects can exist without beliefs in the legitimacy of relics or of works of art in general ever being challenged. Controversies and strategies to discredit relics or rival works of art even act as the proof of the existence of such beliefs, since, if nobody believed in the importance of a relic or of a work of art, nobody would be interested in knowing if the particular objects in question were indeed what it was claimed they were. In eras where relics were seen as important sacred objects, provoking competition between different towns, placed at the heart of controversies over their authenticity, it was very rare to find radical criticism challenging the very notion of a ‘relic’. As Patrick Geary writes:

in general cultural presuppositions on relics, on their value and use were broadly shared. The few dissidents, such as Claude of Turin in the IXth century and Guilbert de Nogent in the XIIth century, were the rare exceptions. From the XIIth century on, some heterodox groups denied the efficacy of relics, but often even these groups had their own versions of saints and even of relics. What was frequently at issue, however, was the identification of a corpse or grave with a saint: how could one be certain that a bone was not simply that of a humble fisherman?79

On the other hand, competition between churches or municipalities claiming to be in possession of the ‘true’ or the ‘genuine’ relics were extremely frequent.80

Relics, like works of art, owe their very particular status to their attachment to a unique person (saint or artist) and the procedures involved in attributing to objects the status of autograph works or that of authentic relics are not left to chance. In the case of relics, this took the form of a public ritual called ‘elevation’, ‘in which the relics were formally offered to the public for veneration’.81 But without any possible recourse to an as yet non-existent science, the authentication of relics depended both on the authority of those who declared them to be authentic and on the miracles attributed to them. For their part, works of art encouraged the development of experts (connoisseurs, art historians, museum curators, art dealers, scientific laboratories) who based all or part of their activity on their capacity to attribute the works circulating within the art market.

Far from being a simple historical detour, revisiting the history of holy relics, provided it is not locked into too rigid a conception of religious history and beliefs, is an essential precondition to the process of understanding the most contemporary practices in the art world. As Thierry Lenain writes:

with this constant fear of the fake and the subsequent development of a culture of authenticity and attribution, the cult of relics therefore seems to us like a striking foreshadowing of our modern art world, which was set up as a result of a transfer of preoccupations and schemes originally anchored in the historical foundations of the Christian Middle Ages. And if it appears difficult to be precise about which channels this transfer operated through, given that its movements are largely hidden away in the deepest layers of cultural history, there is no doubt that we owe to it our conception of the work of art as an ‘auctorial relic’. Still just as relevant in our present times, even when the cult of Christian relics has been relegated to the realm of anthropological vestiges, this change began to take place during the Renaissance. Sources from the time even suggest that it did not stay completely buried in the collective unconsciousness. When Vasari refers to a drawing by Michelangelo which featured in his collection as a ‘relic’, he is thus confirming that the connection had not escaped his notice.82

On the other hand, when, more than two hundred years later, de Quincy compared the battles between museums for the most beautiful paintings to a hunt for relics, the implied criticism demonstrates that the awareness of the structural link between relics and works of art has now been lost.

The separation of art and life

Unquestionably, the work of art, especially an ancient work of art, is untouchable. It merits respect, admiration, reverence and, if possible, understanding. But touch it – never!

Jean-Claude Chevalier, in his preface to a new edition of Don Quichotte, Paris: Seuil, 1997

By becoming autonomous, art not only freed itself from powers (religious, political, economic), it also separated itself from what is not art (crafts, manufacturing). The history of autonomization is not simply that of an emancipation, but also involves a separation of the sacred and the profane and, as a result, a distancing from those who become ‘the cultural public’, ‘spectators’ or ‘consumers of art’. The sanctification of art thus regulates the relationships which can, and indeed must, be maintained between the ‘spectators’, the ‘listeners’, the ‘visitors’ or the ‘readers’ who are not necessarily practitioners, and the artists who participate in a public performance (dance, theatre, music) or who display their work in specially dedicated spaces (libraries and bookshops, museums and art galleries).

Whether it is the stage of a concert or dance venue, the opera or the theatre, with its curtains, stage and footlights separating the public, usually seated, silent and plunged into darkness, and the performers who are under the spotlights; or a museum or gallery with its framed pictures (the frame already distinguishing the work, as Poussin pointed out, in relation to the surrounding continuum and indicating to the visitor where he or she should concentrate their gaze), hung and illuminated, which must not be touched and towards which visitors direct their respectful gaze with neither noise nor gestures; or a library or bookshop which arrange, classify and place on shelves printed works accessible to quietly-behaved borrowers or buyers, the separation of ‘art’ and ‘life’, of the sacred and profane, implies a distancing process and a respectful, admiring and attentive attitude. All the arrangements associated with the works (the physical separation between the stage and the audience, the lighting, the shelves, the temples of art or literature, etc.) objectivize this separation between the work and the consumer of the work, between admired works and admiring public, between what is illuminated and what is destined to remain in darkness, between the space on-stage and off-stage, etc.

These comments on the separation between art and life as a separation between the sacred and the profane belong either above or below any question of internal differences within the various fields defined by Bourdieu (the dispute between ancients and moderns, between academic artists and revolutionary or avant-garde artists, between the commercial approach and the purest one of limited production, etc.). The art world is, certainly, a space within which many confrontations and clashes between aesthetic movements are played out. Yet the very existence of a separate space for creators (painters, sculptors, musicians, dancers, actors, writers, etc.) and their works, in contrast to the profane world of spectators or consumers, deserves to be challenged. It is against the background of this great divide that everything else is played out and acquires its meaning.

These divisions between art and life, between the work and the public, between producers and consumers, between experts and laymen, based as they are on the opposition between dominant and dominated and between sacred and profane make up the structural separations which characterize our societies. They give rise to extremely powerful socializing effects which are all the more powerful because they remain silent and diffuse. These self-evident facts, which are part of the general configuration of our societies, are scarcely investigated now by researchers in social sciences because they belong on a level which is wide-reaching, macro-sociological and many centuries old. They are present therefore as the landscapes structuring all social universes and sub-universes and escape the attention focused at ‘ground level’, which is more generally the domain of sociological investigations designed to describe actors by focusing as closely as possible on their actions and motives.

Only by resorting to history can we become aware of what appears to us to be self-evident. Thus, Mikhaïl Bakhtin points out that the carnival culture of the Middle Ages is a cultural manifestation based on the participation of all and which does not take the form of a separate spectacle on a stage which the audience is simply content to watch:

In fact, carnival does not know footlights in the sense that it does not acknowledge any distinction between actors and spectators. Footlights would destroy a carnival, as the absence of footlights would destroy a theatrical performance. Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people: they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is the laws of its own freedom.83

The carnival is therefore simply life continued under another form, and not, strictly speaking, a form of art distinct from everyday life:

The carnival was not an artistic form of theatrical performance but rather a real (though provisional) form of life itself which was not simply acted out on a stage, but in a sense lived (for the duration of the carnival). That can be explained in the following way: during the carnival, it is life itself which plays and performs – without a stage, footlights, actors, spectators, in other words with none of the specific attributes of any theatrical spectacle – another form of its achievement, that is to say of its renaissance and its renovation on better principles.84

Similarly, the Homeric poems or Greek odes whose historical context is reproduced in a study by Florence Dupont, are not strictly speaking literature or art in the sense in which we understand those terms. If these texts were written in the first place and have survived until our time, if we can now read them and appreciate their form and content, these poems did not exist in written form when they were first written and circulated.85 These were in fact oral poems, improvised by the bards and always associated with events such as banquets, celebrations, the aristocratic symposion and all kinds of different ceremonies. The bard was called upon to improvise until the celebration ended but did not have an already existing work which he then read or declaimed on the occasion of these various events. Poetry was only one element of the celebration amongst others (music, drink, food, women, etc.) and was not seen as a work separated from social life that needed to be listened to and appreciated in a ‘religious’ manner. This is the opposite of the situation experienced by spectators in the societies where art and literature had been invented, ‘a passive public that expressed no opinion on either the choice or the length of the poems that were recited. It was just a public at a spectacle. It attended but did nothing else: its members neither ate nor drank nor courted those seated next to them’.86