: CONTENTS

THE CARES OF A SEPTUAGENARIAN

XX The Solicitous Grandfather 285

XXI The Harassments of Debt, 1817-1822 301

XXII The Hopes and Fears of a Slaveholder 316

XXIII Firebell in the Night: The Missouri Question 328

XXIV Republicanism, Consolidation, and State Rights 345

THE OLD SACHEM

XXV Foundations and Frustrations: The University.

1819-1821 XXVI The Empty Village, 1820-1824 XXVII A Bold Mission and a Memorable Visit XXVIII Life Comes to the University, 1825 XXIX A Last Look at Public Affairs

365

381

397 411 426

FINISHING THE COURSE

XXX The Changing Family Scene XXXI A Troubled Twilight XXXII The End of the Day

447 463

479

APPENDICES

I Descendants of Thomas Jefferson II Jefferson's Financial Affairs III The Hemings Family

Acknowledgments

List of Symbols and Short Titles

Select Critical Bibliography

Index

501

513

515

517 521 537

Introduction

THIS book deals with the life of Thomas Jefferson between his retirement from the presidency on March 4, 1809, and his death at Monti cello on July 4, 1826. It concludes the comprehensive biography entitled Jefferson and His Time. I began work on that in 1943, shortly after the celebration of his bicentennial, and published Jefferson the Virginian on his birthday five years later. In the introduction I stated that I hoped to complete the study in four volumes. By the time I wrote the next introduction I had concluded that five volumes would be required to maintain the scale of the first, and I eventually felt compelled to extend the number to six. Even so, I have left out much I would have liked to include and cannot hope to have done full justice to a virtually inexhaustible subject.

I prudently refrained from making a precise prediction of the time that would be required to complete the task. Like the construction of Mon-ticello this work of historical biography has suffered considerable interruption. During one stretch of six or seven years I could devote practically no time to it. As a result there was a lapse of more than a decade between the appearance of Volume II in 1951 and that of Volume III in 1962. It was in the latter year that I was relieved of academic duties and entered upon the period of technical retirement during which the last three volumes of the work were written. In each of these I have made some reference to the fortunate combination of circumstances which enabled me to remain busy and productive when I might have been turned out to pasture.

This final volume covers more time than any of the others except the first and has the greatest diversity of them all. Because of the variety of Jefferson's activities and the lack of a dominant narrative thread such as was provided by public events when he was in office, I have resorted more often than hitherto to topical treatment. I hope I have been reasonably successful in avoiding excessive repetition on the one hand and imperfect synchronization on the other.

Jefferson was not strictly correct when he said that he had been continuously in public service for forty years. Actually there were a few

breaks, but during almost his entire maturity he had been a public man. Again and again he had contrasted the miseries of official position with the blessings of private life. When he ferried across the Potomac on his way homeward shortly before he became sixty-six, he had no way of knowing that he would never do so again, but he was determined to remain a private citizen. Leaving affairs of state to President James Madison, whom he trusted implicitly, he avoided the very appearance of sharing the determination of public policy.

Though he claimed to be reading Tacitus and Thucydides rather than newspapers, he remained well informed about developments both at home and abroad. His correspondence provides an illuminating commentary on the main events of the time. In his private letters Jefferson spoke with candor and often with extravagance. He was frequently embarrassed by the unwarranted publication of extracts from these. On the other hand he was glad for certain letters of his to be passed around. Some of them were influential, but in general it can be said that he had slight influence on national policies during his retirement. His prestige with his contemporaries increased with the passing years, but posterity was the real beneficiary of his writings.

The blessings Jefferson expected to enjoy as a private citizen were positive as well as negative. Not only would he escape from public cares and quarrels; he would escape to his family, his farms, and his books. This he did, but the results were not in full accord with his sanguine anticipations. He knew he would face financial problems. As an ex-President of the United States he received no pension. At no time did he profit in a monetary way from his writings or his inventions. Already burdened with debt, he had only his farms to depend on. His sad financial history is recorded in considerable detail in this book. Jefferson may have lacked managerial skill, as he himself said, and his absorption in public matters had undoubtedly prevented him from giving his personal affairs the attention they deserved. But his ultimate insolvency was primarily owing to factors beyond his control.

The ex-President, who had so often complained when in office that he was deprived of family life, suffered no lack of it in retirement. His daughter Martha, with her large and growing brood, lived with him at Monticello. A couple of his grandchildren usually accompanied him on visits to Poplar Forest, his second home. He had a dozen grandchildren altogether, including Francis Eppes, the son of his deceased daughter Maria. They adored and revered the kindly patriarch and contributed greatly to his happiness. His hospitality was imposed upon by relatives, but he bore with equanimity his responsibilities as the head of the clan.

The physician who attended him in his last months said that no one could have been more amiable in domestic relations. Life at Monticello was not always tranquil, but Jefferson was at his best as a family man.

In his old age he must have been more aware of the limitations of agriculture as a means of livelihood than when he penned the rhapsody that appeared in his Notes on Virginia, but he continued to regard the cultivation of the soil as the most delightful of occupations. In the long run he may have found rural life less blissful than Horace and Cicero made it out to be. But he found great enjoyment in it — cultivating his garden and riding over his red hills.

In the spring of 1815 he entrusted the management of his Albemarle farms to his grandson Jeff Randolph. He did not cease to be an outdoor man at the age of seventy-two, but he may be said to have attained full stature as a bibliophile and patron of learning about this time. John Adams, reporting that the brightest young Bostonians were eager to visit the Sage of Monticello, introduced several of them to him. Pilgrimages to the shrine increased thereafter.

The Sage sold his superb library to Congress after the British burned the small one in the Capitol in Washington, but he promptly proceeded to assemble another. He now laid less emphasis on law and politics than previously and more on history and the ancient classics, which he read in the original until his dying day.

Not only did he pursue knowledge with delight and encourage others to do so; he served the cause of public enlightenment by creating institutions that were destined to endure. As a champion of individual freedom and self-government, Jefferson tended to minimize the value of institutions and even to fear them. Although a notable President in many ways, he had contributed little to the presidency as an institution. His contributions to executive procedure were not perpetuated. In his last years, however, he gave substance to his undying faith in private learning and public education in the form of a library and a university. He never claimed that he was the founder of the Library of Congress, but it was his virtual creation, and his title as father of the University of Virginia is beyond dispute.

While he himself regarded the establishment of this institution of higher learning as one of the most memorable achievements of his entire life, he failed to obtain for his state a full-bodied system of public education such as he had advocated for half a century. He w as c onv inced t hat only an£nligkt£Jied societ^was capable of genuine self-government an djhat no ign orant people could, maiat girr-rhrh'^od-giv en freedom. In the numerous papers and letters he wrote on this subject he"consistently

championed public education at all levels, laying greatest emphasis on the elementary stage. At the same time he clearly perceived the importance of trained leadership and recognized the usefulness of knowledge. His effort to establish in his own state a temple of freedom and fount of enlightenment is described in detail in this book. I have attempted to follow the long and complicated story of the struggle step by step.

After three or four years of tedious preliminaries, the University was chartered in 1819. This turned out to be one of the most discouraging years in the history of the commonwealth and for Jefferson himself. He had told John Adams that he steered his bark with hope in the head, leaving fear astern. He never ceased to be basically optimistic and his imperturbability in the face of disaster was frequently remarked upon. But the panic of 1819, the Missouri question, and the decisions of John Marshall plunged him into the deepest depression of spirit that he had known since the time of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

He sharply criticized the oligarchic constitution of Virginia and openly advocated its democratization. Although he had no direct responsibility for the state-rights movement in his commonwealth in the 1820's, he strongly supported it in private and was induced to express approval of its principles in public. At this stage, when he had little or no influence on the course of events, he assumed a defensive posture in response /to political developments and in reaction to economic trends. He deplored slavery and believed that ultimate emancipation was inevitable. On the other hand, he recognized the dangers of emancipation and de-\ nied the authority of Congress to intervene in the domestic affairs of a state. Confronted with a contradiction he could not resolve, he left this problem to another generation.

It took him and his supporters six years to make a living reality of the University that existed on paper. During this period there was little or no improvement in the economic situation in Virginia. The state, which lost its primacy in population by 1820, was clearly falling behind in influence and power in the Union. Under these circumstances Jefferson's role as a local patriot sometimes overshadowed that of Sage. He appealed to local interest in behalf of the University and expected it to be a bastion of republicanism against consolidation.

f In certain religious groups he aroused fears that were destined to persist. He was not always wise or tactful, but he consistently supported religious freedom and sought academic excellence. He had to curtail his program somewhat, but the University he created was unique. There was scarcely a thing in the original institution that he did not prescribe and many of his distinctive ideas were to be long-lived. The academical

village, whose beginnings I have had the pleasure of describing, is still intact. In 1976 it was voted "the proudest achievement of American architecture in the past 200 years." 1 It is a pity the author of the Declaration of Independence could not have been present to receive this accolade in person.

Many of Jefferson's contemporaries disapproved of both his buildings and his academic program. Speaking of the latter, one of his most sympathetic guests said that, while it was less impractical than he had feared, he was not sure that the institution could be successful. 2 Throughout Jefferson's career opponents and critics charged him with being an impractical theorist. In his seventy-sixth winter he told a friend that his plan for a complete system of public education in his state might be a "Utopian dream." In the twentieth century it would certainly not have been so regarded; it was merely ahead of its time. The same can be said of other projects of this forward-looking man, and the claim that he was a theorist was owing to more than his specific proposals.

Three decades after his death his granddaughter Ellen said that the main cause for the charge of impracticality against him was "his obstinate propensity to think well of mankind, of human nature, to^putt largely the good sense and good feeling of the mass." 3 Much as she adored him, she did not fully share his democratic spirit. In her opinion the question whether he was right or wrong in trusting the American people as he did had not yet been answered.

It now appears that he expected citizens to be more reasonable than they are likely to be in any age. He made too little allowance for emotions and counted too much on the sufficiency of reason. In my judgment, as in that of John Adams, he underestimated ihe-evil in unrege-nerate man, and time has shown that more is needed to cure the ills of mankind than the accumulation of knowledge. Having said this, I must also say that I regard his faith as the most admirable thing ab6ut him and his most enduring legacy — his faith in human beings and in the human mind. To those who exalt force and condone deception he will ever be a visionary, to be ignored or silenced. But to all who cherish freedom and abhor tyranny in any form he is an abiding symbol of the hope that springs eternal.

'Jefferson's design was selected in a Bicentennial poll of the American Institute of Architects (AlA Journal, 65 [July 1976], 91).

2 George Ticknor to W. H. Prescott, Dec. 16, 1824 (Life, Letters, and Journals, I, 348).

3 Ellen Randolph Coolidge to H. S. Randall, Feb. 13, 1856 (Letterbook, Coolidge Papers, UVA).

It has been my great privilege as a biographer to be intimately associated with this extraordinary man for many years. At the end of my long journey with him I leave him with regret and salute him with profound respect.

Dumas Malone Alderman Library University of Virginia January, ip8i

Chronology

1809

Mar. 4 TJ retires from the presidency.

// He leaves Washington for Monticello, arriving March 15. Apr. ip President Madison proclaims the restoration of trade with Britain under the Erskine agreement. Aug. ip Non-Intercourse with Britain is resumed. Oct. ip-23 TJ visits Richmond.

Dec. 1 He acknowledges receipt of the first volume of Hening's Statutes at Large.

1810

Feb. 2 The Literary Fund of Virginia is established.

July 31 TJ completes a brief for his lawyers on the New Orleans bat-

ture case. Aug. 12 He suggests that William Duane publish Destutt de Tracy's

commentary on Montesquieu.

1811

Mar. 27 Before this date, TJ becomes a great-grandfather upon the birth

of John Warner Bankhead. Apr. 6 James Monroe succeeds Robert Smith as secretary of state. Dec. 5 Livingston vs. Jefferson (the batture case) is dismissed.

Toward the end of the year, TJ begins the manufacturing of cloth at Monticello.

1812

Jan. 1 John Adams renews correspondence with TJ.

Apr. 12 TJ sends William Wirt an account of Patrick Henry.

June 18 War with Great Britain is declared.

1813

Jan. 24 TJ writes John W. Eppes the first of several letters on public finance.

1814

Mar. 2$ TJ is named a trustee of Albemarle Academy. Aug.-Sept. Thomas Mann Randolph, Jeff Randolph, and Charles Bank-head take part in the defense of Richmond.

Aug. 25 TJ assures Edward Coles that the emancipation of the slaves is inevitable but declines active leadership of the cause.

Sept. 7 He writes a letter to Peter Carr describing a scheme of public education.

21 He offers to sell his library to Congress to replace the one

burned by the British on Aug. 24.

1815

Feb. 4-y George Ticknor and Francis Gray visit Monticello. 14 About this time TJ learns of the Treaty of Ghent. Mar. 16 Jeff Randolph is married to Jane Hollins Nicholas. Apr. 18 About this time TJ sends his library to Washington. June 21 Before this date, Jeff Randolph is given the management of TJ's

Albemarle farms. Sept. 18 TJ, accompanied by Francis Gilmer and the Abbe Correa, visits the Peaks of Otter.

1816

Jan. p TJ informs Benjamin Austin that he now supports the development of American manufacturing.

Feb. 16 He learns of the passage of the Central College bill. March Ellen Randolph visits Washington.

Apr. 6 TJ announces the completion of his translation of Destutt de Tracy's Political Economy.

July 12 He writes Samuel Kercheval about the revision of the Virginia Constitution.

Oct. 18 He is named a Visitor of Central College.

1817

Mar. 4 James Monroe is inaugurated as President. May 5 The Board of Visitors of Central College meets for the first time. August TJ travels to Natural Bridge with his granddaughters. Oct. 6 The cornerstone of the first pavilion at Central College is laid.

1818

January TJ sums up his weather records.

Feb. 4 He writes an explanation of confidential papers he had collected while secretary of state.

22 The legislature passes a bill establishing a university.

CHRONOLOGY

XXI

July 30 TJ learns that the Bank of the United States is curtailing all notes, including his. Aug. 1-4 He attends the Rockfish Gap Conference. Aug. 7-21 He visits Warm Springs and leaves seriously ill. Dec. 7, 9 He cancels newspaper subscriptions to all but the Richmond Enquirer.

1819

Jan. Feb.

Mar.

2S

I

is

6

*9

May

Aug. S

Sept. 6

Oct. 31

Dec.

>J

The university bill passes, with Central College as the site.

A fight takes place between Jeff Randolph and Charles Bank-head.

Joseph C. Cabell informs TJ of his appointment as Visitor.

The McCulloch vs. Maryland case is decided by the Supreme Court.

TJ is elected Rector at the first meeting of the UVA Board of Visitors.

He helps set up Stack's preparatory school in Charlottesville.

Wilson Cary Nicholas informs TJ of his failure.

TJ writes Spencer Roane about his Hampden letters.

He writes William Short about being an Epicurean^ and afterwards completes his "Life and Morals of Jesus."

Thomas Mann Randolph becomes_governor of Virginia, serving three terms.

1820

Apr. 3 The Visitors accept Thomas Cooper's resignation.

22 TJ writes John Holmes about the Missouri Compromise. Sept. 21 He instructs Francis Eppes on his trip to the University of

South Carolina. Oct. 10 Wilson Cary Nicholas dies. Dec. 2$ TJ writes to Thomas Ritchie praising John Taylor's Construction

Construed.

1821

January Bernard Peyton succeeds Patrick Gibson as TJ's agent, and Jeff

Randolph takes over the farms at Poplar Forest. Jan. 6 TJ begins his memoirs (leaves off July 29).

31 He writes a gloomy letter to Cabell urging him to remain in the legislature. Feb. 28 The second Missouri Compromise is approved by the Senate. March The Greek War for Independence begins. About this time the

Holy Alliance puts down Italian revolts. April Thomas Sully visits Monticello. June 27 TJ writes Spencer Roane enclosing a recommendation of Construction Construed. Oct. 8 Edmund Bacon leaves TJ's employment.

1822

Jan. 7 TJ writes Thomas Ritchie that he will not be involved in the presidential election.

July 12 He writes William T. Barry about natural political differences among men.

Nov. 28 Francis Eppes marries Mary Elizabeth Randolph. November TJ breaks his left arm.

December He arranges to distribute the Maverick engravings of the University of Virginia.

Mar. 12

May 14-2/

Aug. 2

3*

September

Sept. 23

Oct. 24

Dec.

1823

TJ orders work to begin on the Rotunda.

He mades his last trip to Poplar Forest.

He writes Samuel Harrison Smith on the coming election.

The Spanish revolution is put down.

William H. Crawford suffers a stroke.

John W. Eppes dies at Millbrook.

TJ writes Monroe on the momentous question of foreign rela-

^ tions.

he Monroe Doctrine message is presented.

1824

Mar. 2y Ticknor writes a letter of introduction for Joseph Coolidge.

May Francis Walker Gilmer departs for Europe.

August TJ's recommendation of Bernard Peyton is rejected by Monroe.

September Virginia Randolph marries N. P. Trist.

Nov. i$ A dinner is given for Lafayette in the Rotunda.

Dec. 1 It becomes known that John Quincy Adams has been elected

President.

December Daniel Webster and the Ticknors visit Monticello.

Sept.

Mar. 4

7 May 17

27

30-Oct. 1

Oct. 3 7

IS Dec. 6

December

1825

John Quincy Adams is inaugurated as President.

The University of Virginia opens.

Dr. Dunglison makes his first professional visit as TJ's health

declines. Ellen Randolph marries Joseph Coolidge. Student disturbances occur. The Board of Visitors meets. J. H. I. Browere makes a life mask of TJ. John Quincy Adams sends his first annual message to Congress. TJ drafts a Virginia protest.

CHRONOLOGY

XX111

1826

The public sale o££cjgehill is held. TJ launches his^tterHscheme. Anne Cary Banlcfead-'aies.

TJ asks Madison to take care of him when he is dead. The lottery bill is passed.

TJ executes his will. He adds a codicil on Mar. 17. John Adams writes TJ about the visit of Jeff Randolph. TJ writes his last letter.

TJ and John Adams die on fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

CO

The Return of a Native

FOR a week after the inauguration of his successor on March 4, 1809, Thomas Jefferson continued to occupy the President's House in Washington. James and Dolley Madison would have denied him nothing, but it was no real hardship for them to remain that much longer in their house on F Street. In the afternoon of inauguration day his Washington neighbors presented him with appropriate resolutions to which he made fitting response, and a couple of days later he made a graceful parting gesture to Margaret Bayard Smith, wife of the publisher of the National Intelligencer. That adoring lady, seeing in his cabinet a geranium he had cultivated with his own hands, had expressed the desire that, if he should not take it with him, he would leave it with her. She said she would water it with tears of regret at the departure of "the most venerated of human beings." Sending it to her, he said that this plant could hardly fail to be "proudly sensible of her fostering attentions." In parting with her he found some consolation in her promise to visit Monticello in the summer. This promise she and her husband were duly to carry out, being received "with open arms and hearts by the whole family" just as he now predicted. 1

The retiring President had been winding up his affairs for several months. Early in the year he had obtained loans sufficient to cover the deficit he had incurred while in the highest office. This he now estimated as about $11,000. Thus he was able to settle his current accounts. 2 His trusted overseer at Monticello, Edmund Bacon, had come up to help him pack and move his things. After about two weeks, Bacon set out on the

'Mrs. Smith's note and TJ's reply of Mar. 6, 1809, are in Garden Book, pp. 382-383. The address of Washington citizens and his response are described in Jefferson the President: Second Term, pp. 667-668.

2 Ibid., p. 666, and, in particular, Account Book entries of Jan. 23, Mar. 10, 11, Apr. 19, 1809. His financial situation is described more fully in ch. Ill, below.

return trip. As he afterwards remembered, there were three wagons. Two of them, drawn by six-mule teams, were loaded with boxes. The third, a four-horse wagon, was filled with shrubbery from the nursery of Thomas Main near Washington. 3

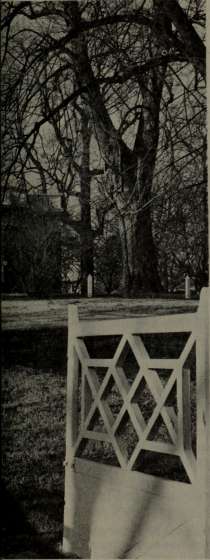

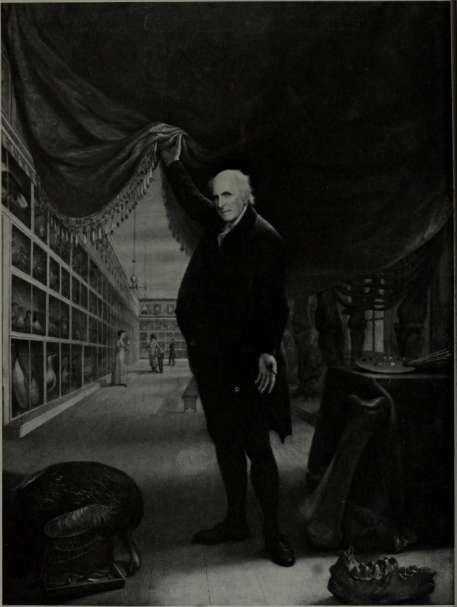

Thomas Jefferson Randolph — whom his grandfather called Jefferson but we must call Jeff to avoid confusion — had already gone home for a brief visit before returning to Philadelphia to continue his higher education. Toward the end of February, Charles Willson Peale, with whom he was lodging, sent the boy's grandfather a portrait of him. Peale reminded his friend that this was painted at the age of sixty-eight by one who had long neglected his art while devoting himself to the "charming study of natural history." (He seemed disposed to yield portraiture to the superior talents of his son Rembrandt.) The recipient of the portrait, who was himself nearing sixty-six, was sure it would do honor to any period of life. He described it as a treasure and took good care that it was preserved. 4

Making a late start on March 11, two days after the departure of Bacon and the wagons, he took the Georgetown ferry for the last time and spent the night at Ravensworth, the home of Richard Fitzhugh in Fairfax County some ten miles from Washington. From his host he got for planting in his garden some peas that were already known by the name of Ravensworth and esteemed highly. 5 He did not reach Monticello until March 15, after what he described to Madison as a very fatiguing journey. The roads were excessively bad, and for eight hours he rode through one of the most disagreeable snowstorms of his experience. He caught up with the wagons at Culpeper and got home before they did. 6

Other belongings of the ex-President were shipped by water — the expectation being that they would proceed down the Potomac to Chesapeake Bay, up the James to Richmond, and thence by smaller vessel to Milton just below Shad well on the Rivanna. The day after he got home he learned that the vessel on which his "baggage" was shipped had gone aground in the eastern branch of the Potomac and was unable to continue its voyage. Accordingly, his things had been put aboard the Dolphin of York. Among these effects was a trunk containing the Indian

3 The journey is described in Bacon's reminiscences, in H. W. Pierson, Jefferson at Monticello (1862), pp. 113-116, referred to hereafter as Pierson. Some allowance should be made for an old man's memory.

4 Peale to TJ, Feb. 21, 1809 (LC); TJ to Peale, Mar. 10, 1809 (LC).

5 The Account Book entry of Mar. 12, 1809, refers to R. Fitzhugh, while the note in Garden Book, p. 400, identifying the place and mentioning the peas, refers to William Fitzhugh.

6 TJ to Madison, Mar. 17, 1809 (L. & B., XII, 266); Account Book, Mar. 14-15, 1809. Bacon's account of events in Culpeper, where he said a crowd had gathered and finally burst into TJ's private room, there to be addressed briefly by him, is rather confused (Pierson, pp. 115-116).

vocabularies, some fifty in number, that he had collected through thirty years. On the last leg of the journey, while ascending the James above Richmond, this trunk was stolen. Toward the end of May a reward for its recovery was offered by his agents in Richmond, Gibson and Jefferson. The description in the notice shows that, besides writing paper, the trunk contained a pocket telescope and a dynamometer, described as "an instrument for measuring the exertions of draught animals." To the distressed owner, his agent and cousin George Jefferson reported in June that papers from the trunk had been discovered in the James below Lynchburg. But George's personal search of the river turned up little of the contents, though the trunk and its thief were afterwards found. Only a few defaced leaves of the vocabularies were saved. In some of his comments on this irreparable loss Jefferson seemed vindictive. Later in the summer he stated with apparent satisfaction that the culprit was on trial and would doubtless be hanged. 7

From his former secretary, Isaac Coles, he learned that the Madisons had moved into the President's House promptly but were not fortunate in their maitre d'hotel, whose insobriety was interfering with his performance of his duties. Thus reminded of his own maitre d'hotel, the former master of that house wrote a generous letter of appreciation to Etienne Lemaire, saying what he had found it impossible to say when parting with those with whom he had lived so long in Washington and by whom he had been served so well. Lemaire's whole conduct, he said, had been "so marked with good humor, industry, sobriety, and economy" as never to have given him a moment's dissatisfaction. He hoped to keep in touch with him and saluted him with "affectionate esteem." Not to be outdone, Lemaire, replying in French, said that, of all the persons he had ever worked for, Jefferson had given him the most happiness and satisfaction, for service of this master was more a pleasure than a task. 8 To another old employee of his, Joseph Dougherty, Jefferson gave what that Irish coachman described as a "noble recommendation." The two carried on animated correspondence thereafter about sheep, especially a broad-tailed ram selected from Dr. William Thornton's flock by Dougherty and designated for paternity at Monticello. 9 The affectionate relations between Jefferson and his domestic staff were

'Isaac A. Coles to TJ, Mar. 13, 1809 (LC); TJ to George Jefferson, May 18, 1809 (MHS); notice of reward offered by Gibson & Jefferson in Richmond Enquirer, May 30, 1809; George Jefferson to TJ, June 12, June 26, July 21, 1809, with enclosure (MHS); TJ to J. S. Barnes, Aug. 3, 1809 (LC); TJ to Dr. B. S. Barton, Sept. 21, 1809 (L. & B., XII, 312-313).

8 TJ to Lemaire, Mar. 16, 1809; Lemaire to TJ, Mar. 22 (LC).

'Among a number of letters reference may be made to Dougherty's of Apr. 19, 1809 (LC), May 15 and 18 (Farm Book, pp. 118-119), and TJ's of June 26 and Aug. 25, 1809 (ibid., pp. 119-120).

Courtesy of tbe Tbomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation; photo by Robert C. Lautman, Washington, D.C.

monticello:

View of the East Front

amply illustrated in both cases. And the parting words of his young secretary were more than perfunctory. At the end of his letter Isaac Coles had said that toward Jefferson his heart would "never cease to overflow with sentiments" to which he had "no power to give utterance."

The mansion house that Jefferson had been building and rebuilding for some forty years was now essentially finished, along with its dependencies. 10 Writing Benjamin H. Latrobe, the American whose architectural judgment he most valued and probably most feared, Jefferson observed: "My essay in Architecture has been so much subordinated to the law of convenience, and affected also by the circumstances of change in the original design, that it is liable to some unfavorable and just criticisms. But what nature has done for us is sublime and beautiful and unique." 11 Visitors to Monticello in the early years of his retirement had much to say about nature, especially in connection with the approach to the house — up an "abrupt mountain" or a "steep savage hill," through "ancient forest-trees." Jefferson himself said that his grounds were still largely in their majestic native woods with close undergrowth. On the ascent nature appeared untamed, and viewed from the summit, five hundred feet above the Rivanna, the vast panorama of forest and mountain was still little marred by the hand of man. Looking at the "spacious and splendid structure" that crowned the height, one observer said: "Here, in this wild and sequestered retirement, the eye dwells with delight on the triumph of art over nature, rendered the more impressive by the unreclaimed condition of all around." 12

It would be nearer the truth to say that nature and art appeared here in notable conjunction, reflecting the deep feeling of Jefferson for them both. Also, his architectural creation represented a distinctive blend of the functional with the aesthetic. The connection of the service wings to the main house by covered passageways provided an excellent example of his practicality; and he manifested his modernity by filling his mansion with convenient devices and flooding it with light. Yet his orders — Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Attic — were designed in strict accor-

10 The plan and its development are described in detail in Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty, chs. 14, 15. An authoritative and convenient modern account is the beautifully illustrated booklet Monticello, by F. D. Nichols and J. A. Bear, Jr. (1967), published by the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation.

11 TJ to B. H. Latrobe, Oct. 10, 1809 (LC, quoted in Garden Book, p. 416).

12 Margaret Bayard Smith, in A Winter in Washington (1824), II, 261. In this work of fiction the descriptions were drawn from the author's observations, such as those she made on a visit to Monticello in the summer of 1809. Among other descriptions I have drawn on at this point are those of J. E. Caldwell, in A Tour through the State of Virginia, in the Summer of 1808, ed. by W. M. E. Rachal (1951), pp. 36-41, and George Ticknor, in his Life, Letters, and Journals, ed. by G. S. Hillard et al. (1876), I, 34-38, describing a visit of 1815.

dance with those of Palladio, while the friezes in the various rooms were adapted from the entablatures of Roman temples. His entrance hall and parlor were filled with busts and paintings. (There were too many paintings, in fact, and the entrance hall was so filled with specimens of natural history that it was already referred to as a museum.) At length he had provided for himself a habitation befitting his extraordinarily diverse and well-rounded personality. It was an expression of his love of privacy, his elevation of spirit, his sophisticated taste, his utilitarianism, his desire for self-sufficiency. The Chinese railing on the terraces was not to be installed for years, and he was to be much occupied with the grounds. Not even now was Monticello wholly complete, but to satisfy his appetite for building he had turned to Poplar Forest, though we shall not follow him to that other home quite yet.

Martha Jefferson Randolph went to Monticello several days before her father's arrival. Throughout his presidency she had made it a practice to be there, along with the children, whenever he was at home. Previously, she had returned to Edgehill after his departure but apparently she did not go back to that place, except for brief visits, after he came home to stay. 13 He had long expected that they would all live together after his retirement, and she had no thought of letting anybody else be his housekeeper. The precise position of her husband in this arrangement is not clear. Thomas Mann Randolph had his own farms to look after, but he appears to have usually had breakfast and dinner at Monticello in this period and to have slept there. A number of his slaves, brought from Edgehill, were housed on the place. The situation could not have been wholly congenial to this proud and sensitive man, but he does not seem to have fretted under it particularly.

He was now forty-one, while Martha was thirty-seven, and their children numbered eight. The eldest, Anne Cary, now eighteen, had been married in the previous fall to Charles Lewis Bankhead. Since the young couple lived at Carlton on the western slope of Jefferson's little mountain, he saw a great deal of this favorite granddaughter. 14 Her brother Jeff, whose portrait Charles Willson Peale had painted, was sixteen when he rode to the Capitol with his grandfather for the inauguration of James Madison. As expected, he returned briefly to Philadelphia for botanical lectures, but he did not go to the College of William and Mary the next

n See Family Letters, p. 384, note 2. For a map of the Monticello neighborhood, see below, p. 254.

14 See the account of Anne and her husband by Olivia Taylor in George G. Shackelford, ed., Collected Papers . . . of the Monticello Association (1965), ch. V. Her troubles because of the alcoholism of her husband became acute by 1815, if not earlier.

Courtesy of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation; photo by George M. Cusbing, Boston

Thomas Jefferson Randolph Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, 1808

year as his grandfather had planned. Jefferson had become convinced of his grandson's industry and sobriety, and as time went on depended on him more and more, but it was clear that the robust lad's interests were not primarily intellectual. It was adjudged sufficient for him as a prospective planter to complete his formal education by attending the school of Louis H. Girardin in Richmond during i809-1810.

After Jeff came four girls, ranging in age from five to twelve, all of whom went to school to their mother. The eldest, Ellen Wayles, had already shown herself to be a diligent correspondent, and she was to be Anne Cary's replacement as guardian of the flowers. Edmund Bacon said that these two girls, like their mother, had the fresh, rosy look of the Jeffersons, while most of the other children tended to be dark, like theif father. 15 There were two little boys: one, born in the President's House and now aged three, was name d James M adison^ while the bai>y^still in his first year, bore the distinguished name of Benjamin Franklin. As though these were not enough, there were to be three more children, and young Francis Eppes, the son of Jefferson's lamented daughter Maria, was often at Monticello. In the winter of 1809-1810 when he was eight, he was engaged in a spirited contest with his cousin and contemporary Virginia Randolph in the art of reading.

As a father and grandfather Jefferson received the warmest of welcomes when he dismounted at Monticello. He would have been escorted to the door by a body of friends and neighbors if they had had their way. A group of citizens of Albemarle had wanted to meet him at the county line and conduct him home. They gave up the idea when informed that the precise day of his arrival was uncertain, but, before this came around, a group met at the courthouse and adopted an address in the name of all the inhabitants of the county. Since he was receiving messages from all over the Union, they could add nothing "on the score of public gratitude," they said. Referring, as so many other addresses and resolutions did, to his "voluntary relinquishment of honors and of power," they rejoiced in the restoration to them of "a friend and neighbor as exemplary in the social circle, as he is eminent at the helm of state." There was no intimation here of any sort of public failure or moral turpitude on his part. And, although these sentiments could hardly have had unanimous support in Albemarle, this affectionate address shows unmistakably that he was held in the highest honor in his own locality.

Presumably the gentlemen of the committee who had drafted the ad-

ls Pierson, pp. 86, 88. For detailed information about the family members, see Appendix 1, below.

-A

dress bore it to Monticello and presented it in person. 16 The episode must have reminded Jefferson of the welcome he had received from his Albemarle neighbors on his return from France some twenty years before. 17 In the memorable address he made on that occasion he spoke of "the sufficiency of human reason for the care of human affairs," and of the will of the majority as "the only sure guardian of the rights of man." He urged his hearers forever to "bow down to the general reason of society." They were safe in that, he said, for although it sometimes erred, it soon returned to the right way. After observing the most philosophical phase of the French Revolution in 1789 he had been in an optimistic frame of mind. Now, receiving with "inexpressible pleasure" the cordial welcome of his local fellow citizens, he was personal rather than philosophical. He said that for the joys of affectionate association with them and the endearments of domestic life he gladly laid down "the distressing burden of power," and the measure of his happiness would be complete if his public services had received the approbation of his countrymen. In some sense he was on the defensive, though these approving neighbors had certainly not put him there. Of them he could ask with confidence, "Whose ox have I taken, or whom have I defrauded? Whom have I oppressed, or of whom have I received a bribe to blind my eyes therewith?"

An occasional visitor to Jefferson's native district asserted that he was not highly regarded by his neighbors, but the burden of testimony gives the opposite impression. Of his own attitude toward the locality which was in the deepest sense his "country" there could be no doubt whatsoever. Writing a distinguished foreign explorer and savant, now settled in Paris, he had recently said: "You have wisely located yourself in the focus of the science [knowledge] of Europe. I am held by the cords of love to my family and country, or I should certainly join you." 18 Nothing seems to have been farther from his thoughts than another trip to the vaunted scene of Europe, but he was not far from the literal truth when he said that he was burying himself in the groves of Monticello.

In late September of the year of his homecoming, shortly before Madison returned to Washington, Jefferson visited his friend and successor

16 From the account of the episode in the Richmond Enquirer, Apr. 14, 1809, we learn that the citizens met at the courthouse in Charlottesville on Mar. 6 and 11. The committee consisted of William D. Meriwether (chairman of the meetings), Nimrod Bramhan, Dr. Charles Everitt, Thomas W. Maury, and Dabney Minor. Meriwether wrote TJ, Mar. 23, 1809 (LC). The Enquirer published both the address and TJ's reply. The latter, dated Apr. 3, is in L. & B., XII, 269-270. See also Martha to TJ, Feb. 24, 1809 {Family Letters, p. 384); TJ to TMR, Feb. 28 (L. & B., XII, 256-257).

11 See Jefferson and the Rights of Man, pp. 246-247.

18 To Baron Alexander von Humboldt, Mar. 6, 1809 (L. & B., XII, 263).

YLAND

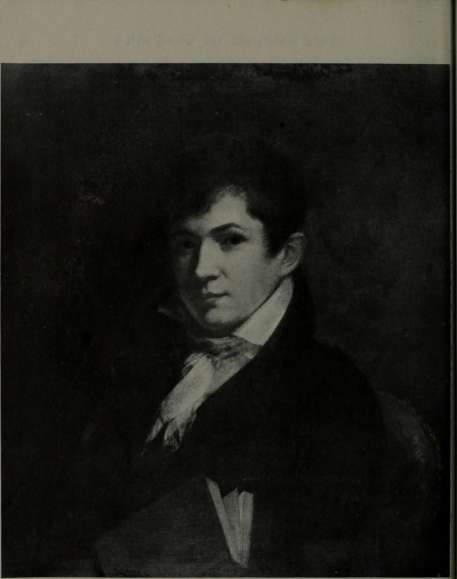

Jefferson's Country, 1809-1826

\

14 THESAGEOFMONTICELLO

at Montpelier. During the rest of his life he did this almost every year, but Orange County was the closest he was to get to the capital of the Republic. Only once during the seventeen years of his retirement did he visit the capital of his own commonwealth. In the fall of this first year he went to Richmond on business, and there he received a very hearty welcome. 19 Learning of his presence, a group of citizens met at the cap-itol the morning after his arrival. They unanimously adopted resolutions of respect and admiration for his exalted character and of gratitude for his distinguished services. A committee was appointed to prepare an appropriate address. In his gracious reply to this he claimed no other merit than that of having contributed his best endeavors to the "establishment of those rights, without which man is a degraded being." He hailed these citizens as fellow laborers in the same holy cause.

The honors paid him on this apparently unannounced visit seem to have been spontaneous. About the same time that resolutions were being adopted at the capitol, a drill muster of the 19th Regiment took place on capitol square. The officers, learning of Jefferson's arrival, invited him to dine with them at 4 p.m. that day. In due course he was escorted from .the Swan Tavern with Governor John Tyler, Colonel James Monroe, and others. Among the toasts was one he offered to "the militia of the United States — the bulwark of our independence." On the next day there was a public dinner in his honor at the Eagle Tavern. A large and brilliant company were said to have attended. After Jefferson's retirement, Governor Tyler toasted him as "first in the hearts of his country." 20 If by Jefferson's country the Governor meant Virginia rather than the United States, the saying was doubtless true, and in the physical sense he was henceforth nothing but a Virginian. Until his dying day he never left the state. Late in his life he went once to Warm Springs, the westernmost point of all his travels, but he never returned to Richmond, and except for Montpelier, almost the only other place he went to was his own Poplar Forest.

He had good reason to visit the farms in Bedford County that constituted almost half of his estate, but during his presidency he was unable to make this journey of ninety miles more than once a year. According to family tradition he conceived the idea of building a house at Poplar Forest when confined for three days by rain in one of the two rooms of an overseer's cottage there. 21 The idea was natural enough in any case,

"Account Book, Oct. 15-31, 1809, shows that he visited Carysbrook, Clifton, and Ep-pington both going and coming and was in Richmond Oct. 19-23.

20 The events of this visit, including the resolutions, address, and two dinners are described in Richmond Enquirer, Oct. 24, 1809.

but he does not appear to have considered it seriously until he relinquished the purpose of building at Pantops in Albemarle County the house originally intended for his daughter Maria and John W. Eppes. This was during his first presidential term and not long after he designed Farmington for his friend and fellow horticulturist George Divers. 22 In this period he was experimenting with octagons in combination with rectangles. The plan for Poplar Forest, novel in America then and distinctive at any time, called for a regular octagon that centered on a square room lighted from above and that had porticos on the front and rear. 23 Work on the building was begun in 1806; the walls were up by the fall of 1808; and Jefferson was able to stay in the house when he visited the place a year later. 24 Plastering did not begin until two years after that, and the house that Jefferson called his retreat and designated as a legacy to his grandson Francis Eppes was long to remain unfinished. Its completion was not to require a generation, as that of Monticello did, but this was to take upwards of a dozen years.

It turned out to be an architectural gem in a harmonious setting that pleased its designer and builder. His visits to it increased in number and duration. From the second year of his retirement until he stopped traveling altogether he averaged three a year. His life there can be more fittingly described after this really became his second home; but we may note here that virtually the whole of his seventeen years of retirement was spent in the red-clay country and that, the weather permitting, he was nearly always in sight of the mountains. 25

At the beginning of his retirement at Monticello he established a regimen from which he departed little thereafter. He continued to rise by daybreak — that is, as soon as he could make out the hands of a clock he kept beside his bed. He then recorded the temperature. Sometimes his overseer observed him walking on the terrace in the dawn's early light. Usually he started on his necessary correspondence as soon as he could, hoping to get this done by breakfast. Judging from the accounts of visitors, that meal was at nine. One wonders if he had tea or coffee when he arose. At first he seems to have managed to visit his garden and

22 The house with later additions is now the Farmington Country Club, near Charlottesville. See the map, below, p. 254.

23 Fiske Kimball, Thomas Jefferson, Architect (1916), pp. 70-72, relates the plan to TJ's studies for Farmington and to a design of Inigo Jones for a larger and more elaborate building. See also F. D. Nichols, Thomas Jefferson s Architectural Drawings (1961), pp. 7-8 and Plate No. 29, reproduced below, p. 295.

24 See Hugh Chisholm to TJ, Sept. 4, 1808 {Garden Book, p. 377). Chisholm was a brick-mason, among other things, and was dispatched from Monticello to Poplar Forest as other workmen were.

25 His route to Poplar Forest is marked on the map, above, p. 1}. For further reference to life there, see ch. XX.

/ shops and begin to ride about his place soon after breakfast. This he did for health and pleasure, and also to note the state of his property and I crops. When his correspondence increased, with the passing months, he had to stay indoors longer, but even then he generally began his daily ride by noon. 26 On this he customarily wore a pair of overalls. By all accounts he was an uncommonly fine horseman, and in extreme old age he said that life would have been unbearable without this daily revival. 27 His ride lasted until he came in for dinner, a meal that seems to have generally begun about four in the afternoon and to have continued long. He said that he gave the time from dinner to dark to the society of neighbors and friends, and that from candlelight to early bedtime he read. When there were no special guests he may have done this in the company of members of his family, who were engaged in sewing or knitting or something else. According to some accounts, however, he customarily retired to his quarters after tea, which was served about seven.

He referred repeatedly to his beloved books and he crowded an incredible amount of reading into his last years, but during the first of them he rejoiced in his opportunity to be an outdoor man, concerned with practical affairs. u My health is perfect," he reported to General Thaddeus Kosciuszko in 1810, "and my strength considerably reinforced by the activity of the course I pursue; perhaps it is as great as usually falls to the lot of near sixty-seven years of age." (When sixty-eight he had an attack of rheumatism which reduced his walking but did not long affect his riding.) Edmund Bacon, whose acquaintance with him did not begin until Jefferson was sixty-three, thus described him: "Mr. Jefferson was six feet two and a half inches high, well proportioned, and straight * as a gun-barrel. He was like a fine horse — he had no surplus flesh." 28

\rtO

T

here were many references to his tall and slender figure, and others described it as little impaired by age, but few observers may have realized, as his overseer did, how strong he was. He had a machine for measuring strength, and very few of the men that Bacon saw try it were as strong in the arms as Thomas Mann Randolph, but Jefferson was stronger than his son-in-law. According to Margaret Bayard Smith, at the time of her visit to Monticello in August 1809, his white locks announced an age that was contradicted by his "activity, strength, health,

26 Among the best accounts of his regimen in his early years of retirement are those he gave Thaddeus Kosciuszko, Feb. 26, 1810, and Dr. Benjamin Rush, Jan. 16, 1811 (L. & B., XII, 369-370; XIII, 1-2).

27 Comment of Bacon (Pierson, p. 74); TJ to Wm. Short, Apr. 10, 1824, quoted in Farm Book, p. 87, at the beginning of a detailed account of TJ's horses.

28 Pierson, p. 70.

enthusiasm, ardor and gaiety." 29 To Kosciuszko he wrote a few months later: "I talk of ploughs and harrows, of seeding and harvesting, with my neighbors, and of politics too if they choose, with as little reserve as the rest of my fellow citizens, and feel at length the blessing of being free to say and to do what I please without being responsible to any mortal." This was the sort of life he wanted to lead — the sort of life that had been extolled by ancient writers he knew well — Cicero and Horace and the younger Pliny. But there were practical difficulties, chiefly financial, from which there was no escape and which were eventually to bear him down. And he could not get entirely out of public affairs all at once. There were loose ends to tie up, and he could never be wholly a private man.

29 Comment of Aug. 3, 1809, in Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. by Gaillard Hunt (1906), p. 80.

ra

Presidential Aftermath 1809-1811

ON the eve of his retirement Jefferson said that if the country should meet misfortunes it would be "because no human wisdom could avert them." 1 There can be no more doubt of his confidence in his successor than of his relief in "shaking off the shackles of power." By this time he actually had little power left to shake off. As soon as the election of Madison was unquestionable, he had shifted to this trusted colleague all the responsibility he could, and the form that the final legislation of his presidency assumed was chiefly owing to others. 2

In the existing state of world war the entire avoidance of misfortune was indeed beyond American wisdom. In his inaugural address Madison described the international situation as unparalleled, and the situation of his own country as full of difficulties. Neither in public nor in private did he blame his immediate predecessor, who, as he said somewhat elaborately, was now enjoying "the benedictions of a beloved country, gratefully bestowed for exalted talents zealously devoted through a long career to the advancement of its highest interest and happiness." 3 One 'would have great difficulty in finding anywhere in the papers of either of these longtime friends and associates any reflection on the policies or conduct of the other. The historian may properly ask, however, what sort of legacy the third President left the fourth.

For the unparalleled state of world affairs neither was responsible; and in the foreign policies that had been followed by the government it is almost impossible to distinguish between them. Madison had no apologies for a course he regarded as unexceptionable, but he recognized that

'TJ to Du Pont de Nemours, Mar. 2, 1809 (J--D. Correspondence, p. 122).

2 The developments during the final congressional session of his administration are treated in detail in Jefferson the President: Second Term. See especially chs. XXXIV-XXXV1.

it had not availed against "the injustice and violence of the belligerent powers." He made no specific reference to the embargo or to the modified policy of commercial restriction that was embodied in the Non-Intercourse Act as adopted at the very end of the congressional session. 4 While this measure did not mark an abandonment of the principle of economic coercion and was not hailed as a glorious victory by the anti-administration forces, it would not have been adopted in this reduced form but for the violent opposition that had been directed against the laws it superseded. On the eve of Madison's accession the government of Connecticut and the General Court of Massachusetts were defying the executive in Washington along with the embargo. While Jefferson's policies may be said to have saved the West to the Union, they had finally played into the hands of his enemies in New England and accentuated disaffection in that commercial region. The unity of the party, which he had maintained hitherto with such conspicuous success, was breached jn the last half of his final congressional session by the revolt of members from the Northeast. Under these circumstances the executive branch lost the initiative that Jefferson had generally maintained. Thus his successor inherited not only a dislocated economy but a divided country and a divided government. Furthermore, it soon appeared that Madison wa^ presiding over a divided Cabinet.

Faced with the opposition of a senatorial group that included Samuel Smith of Maryland, William Branch Giles of Virginia, and Michael Leib of Pennsylvania, he abandoned his purpose to have Albert Gallatin as secretary of state and appointed Robert Smith, brother of the Senator, to that key post, no doubt expecting to write the diplomatic dispatches himself. Gallatin remained as secretary of the treasury. Madison may be charged with weakness in yielding to this senatorial faction at the outset of his administration and may be compared unfavorably to Jefferson in his relations with Congress. Indeed, a contrast has been drawn between the Madisonian "model" of government, with its emphasis on checks and balances, and the "system" of Jefferson, which is said to have collapsed under his successor. 5 To Jefferson, who stressed political party and majority rule, has been attributed the exercise of presidential leadership with unparalleled skill and effectiveness. The reference is not to his last congressional session, however. The same senatorial faction that blocked Madison's nomination of Gallatin had rejected Jefferson's of William

4 Act of Mar. 1, 1809, repealing the embargo and providing for non-intercourse with Great Britain and France and the opening of trade with other countries (Annals, 10 Cong., 2 sess., pp. 1824-18 30; discussed in Jefferson the President: Second Term, pp. 648-649).

s James MacGregor Burns, The Deadlock of Democracy (1063), chs. 1, 2; see also pp. 265-267, 338. By the "model" of Madison is meant the one he set up in the Federalist, especially No. 51.

20 THESAGEOFMONTICELLO

Short. Nor does it seem that, even at the time of his greatest effectiveness as a leader, he differed much from his Secretary of State in basic theory. Opposed to any sort of tyranny as he was, Jefferson adhered in principle to the division of powers and favored a limited as well as a balanced government. These doctrines served to inhibit him — not only because they were generally approved by his countrymen but also because he accepted them himself. In practice, though, he was disposed to be pragmatic. His exercise of leadership in legislative matters during much the larger part of his administration provides a striking example of this, but in deference to Congress and the doctrine of separation of powers, he kept out of sight insofar as possible. Procedure that was not formalized or even openly acknowledged could not have been expected to set a firm precedent. It may be doubted if any other President has ever employed party loyalty more effectively to procure legislation, but his party^ leadership was essentially personal, and from almost the beginning to almost the end it was undisputed. Madison occupied no such position of advantage. Nor did he have comparable skill in conciliating dissidents or equal ability to gain and maintain personal loyalty.

Jefferson's public image, like his physical stature, was more impressive than Madison's, but it was not that of a charismatic chieftain. Rather it was that of a friend of mankind who would ask no more of his fellows than he had to. His popularity, at least until the period of the embargo, was owing in no small part to the fact that he asked little. His domestic program was distinctly limited. He sought to maintain the freedom of his country and countrymen and to make the republican experiment a success. On the world front he was generally engaged in a holding operation; nearly always he was playing for time. His superiority to his friend and colleague in presidential leadership can be best attributed to his personality and the circumstances by which they were confronted. Although alrtrong President when at his best, he obviously weakened at the end; and it may be doubted if he measurably strengthened the presidential office.

From the beginning of their intimate association Jefferson had treated Madison as a peer, and he had yielded the helm to him as soon as possible. He would have been out of character if he had sought to dictate to his successor, and in fact he scrupulously avoided any suggestion of interference. 6 From their correspondence it appears that their personal relations were wholly unaffected by their change in status and that entire candor was maintained between them. During Madison's first summer

6 Their relations were well analyzed by R. J. Honeywell in "President Jefferson and His Successor" (AJJ.R., XLVI, 64-75). In recent writings there has been no such over-emphasis on the former as he perceived at that time (1940).

as President he visited Jefferson at Monticello in company with Albert and Mrs. Gallatin. Unfortunately, we have no record of their private talk, but judging from their correspondence, Madison usually asked for advice only on matters carried over from Jefferson's administration or relating to it. He reported foreign affairs to his friend promptly and fully. Jefferson's comments on events were mostly meant to be encouraging.

At the outset the general impression seems to have been that the administration of Madison amounted to a continuation of Jefferson's and the initial rejection of his nomination of John Quincy Adams as minister to Russia and his forced abandonment of his plan to have Gallatin as secretary of state would lead one to suppose that the new President was as powerless at the beginning as the old President at the end. After the brief executive session of the Senate, called to consider appointments, the President was free of immediate congressional supervision until the beginning of the special session on May 22. Meanwhile, at Monticello, spending more time indoors than he liked because of the cold and backward season, Jefferson was considerably occupied with answering the many addresses and letters from Republicans that manifested their continued loyalty to him.

About a month after he got home and about a week after his sixty-sixth birthday he received highly gratifying news from Washington. He learned of the declaration of the young and friendly British minister, David Erskine, that the Orders in Council of January and November, 1807, against which his own government had so strongly protested, would be withdrawn on June 10. He also learned that, in turn, Madison had proclaimed the renewal of the commerce with Great Britain which had been proscribed. 7 One feature of the surprising Erskine agreement Jefferson regretted — the prospective sending by the British of an envoy

(extraordinary to negotiate a trade treaty. In his opinion they had never been known to make an equitable commercial treaty, and none could .therefore be expected. Nevertheless, he rejoiced in the apparent British retreat as the triumph of the "forbearing and yet persevering system" of the American government. He told Madison that the agreement would give the country peace in his administration, and by permitting the extinguishment of the national debt would open to them "the noblest application of revenue^that has ever been exhibited by any nation." No doubt the ex-President was thinking of the program of internal improvements and education he and Gallatin had had to forgo. 8

7 Erskine's communications of Apr. 18, 19, 1809, Madison's proclamation of the latter date, and his letter of Apr. 24 to TJ are in Hunt, VIII, 50-53. TJ commented in a letter to Madison, Apr. 27 (L. & B., XII, 274-277).

* See Jefferson the President: Second Term, pp. 553-560.

.

These events stimulated his imagination. While declaring that the policy of the French Emperor was so crooked as to elude conjecture, he himself engaged in a good deal of the latter — not merely with respect to the revocation of the French edicts in response to the British action, but also regarding expansion into Spanish territories and former colonies that seemed to be slipping from Napoleon's control. Besides the Flori-tfas, his aspirations for his country as now expressed extended to Cuba. Beyond that southern outpost he would not go, but he still had hopes of including £anada in "our confederacy." Then, he said, they would have "such an empire for liberty" as had not been surveyed since the creation. And he was persuaded that "no constitution was ever before so well calculated as ours for extensive empire and self-government." 9

The shocking news that the Erskine agreement had been repudiated by the British government reached him in early August. Such euphoria as it had created lasted not more than three months, and both he and Madison began to have doubts at least a month before that. 10 Madison had to issue another proclamation, restoring the prohibition of trade with Great Britain as required by the Non-Intercourse Act. Jefferson at Mon-ticello, more convinced than ever of British chicanery, wrote Madison that if Bonaparte should have the wisdom to "correct his injustice" against the United States, war with Great Britain would be inevitable. While expressing continued confidence in Erskine's integrity, he spoke of the "unprincipled rascality" of Canning and described the present ministry as the most shameless that had ever disgraced England. And he sought to reassure his mortified successor by holding that both of Madison's proclamations were entirely proper under their respective circumstances. 11 The net result of these developments, according to Gallatin, was to leave the nation in a weaker condition than it had been a year earlier. 12 Thus it would seem that the Madison administration, instead of being credited with a plus mark, should have been charged with a minus, and one would have supposed that the President's credibility would have suffered. No doubt it did, but most Federalists appear to have been restrained in their early criticism. Some sharp things were said in especially pro-British papers, but in contrast to his predecessor

9 L. & B., XII, 277. He did not allow for the increase in the slave population of the country that would result from the acquisition of Cuba. On the Floridas, see ch. VI, pp. 86-88, below.

,0 For an authoritative account of this from the British point of view, see Bradford Perkins, Prologue to War (1963), pp. 207-209. See TJ's comments to Madison, June 16, 1809 (Ford, IX, 255-256); Madison's to TJ* June 20 (Hunt, VIII, 60-61).

"TJ to Madison, Aug. 17, 1809 (L. & B., XII, 304-305, supplemented from LC). Perkins takes a much more favorable view of Canning {Prologue to War, pp. 210-220).

12 Gallatin to John Montgomery, July 27, 1809 (cited, ibid., p. 219).

he was not subjected to grave personal abuse. Thus far the Federalists preferred him to Jefferson.

The Erskine agreement, which seems to have been more widely and more enthusiastically hailed than the Louisiana Purchase, had been attributed in Federalist circles to the escape of the administration from the influence of Jefferson. One writer declared that it was owing to "fortuitous circumstances abroad, and a disposition not perverse in the new president." Said a Federalist editor: "Our only fear respecting Mr. Madison has been that he would be influenced by his predecessor." 13 Even after the repudiation of the Erskine agreement, there was a disposition in Federalist circles to absolve him from blame for the crisis. The source of the country's troubles, alleged one paper, was to be found in the eight years preceding him. 14

Speaking of his own proceedings, Jefferson said that the "republican portion" of his fellow citizens had viewed them with indulgence. His friend Benjamin Rush congratulated him on the "auspicious issue" of his "free and protracted negotiations" with the British. The Richmond Enquirer copied from a western paper a Latin quotation which, while making him the major luminary, sought to honor both him and his successor. In translation it read: "The-sun retires, but darkness does not follow." An even better expression of predominant Republican sentiment was the toast that Thomas Ritchie, editor of the Enquirer, gave at a Fourth of July celebration: "Thomas Jefferson and James Madison — the same in principle — the same in measures — the same in the confidence of their country." 15

Ritchie, always a seeker after party unity, was well aware of what the Federalists were saying. So was Madison himself. Writing Jefferson about a week after the special session of Congress began, he said: "Nothing could exceed the folly of supposing that the principles and opinions manifested in our foreign discussions were not, in the main at least, common to us: unless it be the folly of supposing that such shallow hypocrisy could deceive any one." 16 In fact there was reason to believe that Madison was less anti-British than his predecessor and thus in a somewhat better position to negotiate. Jefferson's Chesapeake proclamation had been a stumbling block, and, while this was not formally disavowed, one feature of the modified policy represented by the Non-Intercourse Act

13 Charleston Courier (a relatively moderate paper), May 2, 1809, quoting communication in Baltimore Federal Gazette; Charleston Courier, May 10, 1809, quoting Freeman s Journal.

XA Charleston Courier, Aug. 23, 1809, quoting Virginia Gazette; see also Aug. 21.

,5 TJ to William Lambert, May 28, 1809 (L. & B., XII, 284); Rush to TJ, May 3, 1809 (Butterfield, II, 1003-1004); Richmond Enquirer, May 10, quoting Missouri Gazette; ibid., July 7, containing Ritchie's toast.

16 Madison to TJ, May 30, 1809 (Hunt, VIII, 61-62).

was that French as well as British warships were excluded from American waters. This modification he may be presumed to have acceded to, however, and Madison was entirely warranted in saying that their political enemies were seeking to make a distinction where there was no difference worthy of the name.

Both Madison and Jefferson were anathema to John Randolph, erstwhile Republican turned perennial gadfly. At the beginning of the special session of Congress he introduced a resolution calling for an inquiry into the financial transactions of the government during Jefferson's two terms. The main question he raised was whether the moneys had been properly applied to the objects for which they were appropriated. But Randolph's friend Nathaniel Macon, after affirming his own belief in the propriety of investigating the money affairs of any and every administration whenever a President retired, made this observation: "I feel no hesitation in saying that the nation will never be blessed with such another Administration as the last." John Randolph, hastening to say almost the same thing with a quite different meaning, provided one of the most memorable and most unfavorable characterizations of the Jeffersonian regime:

I do unequivocably say that I believe the country will never see such another Administration as the last; it had my hearty approbation for one half of its career — as to my opinion of the remainder of it, it has been no secret. The lean kine of Pharaoh devoured the fat kine; ... I repeat it — never has there been any Administration which went out of office, and left the nation in a state so deplorable and calamitous as the last. 17

In contrasting Jefferson's two terms this embittered critic did not allow for the intensification of the duel between Great Britain and France, and for the shrinkage in the options of neutrals. In calling for an inquiry into the expenditures of the recent government, furthermore, he was not attacking it at a point of particular vulnerability. It may have been less economical than it claimed to be, but it had been notably scrupulous and free of scandal. Nothing much came of this resolution. The committee made an incomplete report which was tabled. 18 The retired President does not appear to have been at all perturbed by this move, or gesture,

xl Annals, n Cong., i sess., I, 69; see also pp. 63-64, 66, 68. 18 June 27, 1809 (ibM-> P- 448)-

PRESIDENTIAL AFTERMATH

25

of his inveterate critic, but he was disturbed by another resolution from the same hand, calling for an inquiry into prosecutions for libel in the federal courts and pointing to the libel cases in Connecticut. This caused Jefferson to write letters to Congressman Wilson Cary Nicholas and Postmaster General Gideon Granger, who had been his intermediary in this matter. As we have noted elsewhere, Jefferson's private explanation of his own connection with these abortive prosecutions for libel leaves something to be desired, but he was clearly not responsible for starting them, and the statement that Granger published in midsummer appeared to bring that controversy to a satisfactory conclusion. Not even the Connecticut Federalists entered into it with eagerness at this time. 19

It should certainly not be supposed that Jefferson's old political foes ceased attacking him. During the first months of his retirement, while most of the Federalists were applauding Madison for his apparent diplomatic triumph, a two-volume work, entitled Memoirs of the Hon. Thomas Jefferson, was published in New York. 20 It was better described by one of its subtitles, for it purported to give "a view of the rise and progress of French influence and French principles" in the country. This was distinctly a High Federalist view, pro-British and anti-democratic. Fol-i lowing the strict party line that had been laid down in the previous decade, the author identified Jefferson with these baleful French ideas, but he gave relatively slight attention to the recent President in the first volume. In the second that gentleman was described as "weak, visionary, timorous and irresolute, destitute of fortitude, destitute of magnanimity," and he was said to have brought the country to ruin at home and disgrace abroad. 21 Jefferson does not appear to have possessed a copy of the book and may never have learned from it that his principal characteristic was duplicity. He still subscribed to the Philadelphia Aurora, however; and, though he claimed that he was doing little reading of newspapers, he could have seen there William Duane's comment on the work as "a satire of the American people, and disgrace to the press, and to human nature." 22

The National Intelligencer responded to what it called the "clamorous abuse" of the ex-President even before Duane sought to expose the author. Samuel Harrison Smith published a series of ten articles under the

"There is a detailed account of these cases in Jefferson the President: Second Term, ch. XXI. Developments after TJ's retirement are described on pp. 388-391.

20 Attributed to Stephen Cullen Carpenter. Right to title registered June 7, 1809.

21 Memoirs of the Hon. Thomas Jefferson, II, 90.

22 Philadelphia Aurora, Aug. 21, 1809. Duane, who was avidly anti-British, noted the anonymous publication Aug. 17 and referred to it a number of times thereafter. Saying that it was the work of Stephen Cullen, who had added the name Carpenter, Duane charged him with being a British pensioner.

title "Defence of Mr. Jefferson's Administration." 23 Smith blamed this abuse on the spirit of a faction: "Professing an unbounded respect for the present Chief Magistrate, it daringly carries the dagger to the heart of his best friend." Jefferson, who was here referred to as the Sage of Mon-ticello, was said to need no defense, but, week by week, he received one. The successive articles dealt with practically all the controversial issues of his presidency. Smith might have made more of the Louisiana Purchase and have claimed less for the embargo than he did.

After the repudiation of the Erskine agreement, some Federalists were intimating that the difficulties confronting Madison were not of his own making. Thus one newspaper said: "Again we are inflicted with the king's evil: I mean the evil of the 'illustrious Jefferson'." 24 It is hard to determine the precise point at which Federalist praise of Madison turned to blame and he ceased being compared with Jefferson to the latter's disadvantage. Perhaps his first address to Congress marked a turning point. Disappointment was expressed that he gave no hint of a policy. Said the Connecticut Courant: "We are left to grope our way in the dark, without one ray of light." 25

Of more abiding interest was a veiled attack on Jefferson, made at the very end of 1809, which escaped from the heavy-handedness that characterized virtually all other partisan attacks on him and, unlike them, gained for itself a place in literature. About Christmastime appeared A History of New York by Diedrich Knickerbocker — that is, Washington Irving. In this fanciful and witty work the character of William the Testy was modeled in part on Jefferson; and his administration is satirized in the account of the administration of the seventeenth-century Dutch governor Wilhelmus Kieft. 26

The picture is inexact: William the Testy was a small man, given to violent outbursts of temper, impatient of all advice. Jefferson did not look like that, and those who knew him best would never have agreed that he was passionate and unreasonable. Unlike William the Testy, he was not enamored of metaphysics and he was too utilitarian to find enduring delight in abstractions.

Nevertheless, along with some wide misses, the young author made some palpable hits — poking fun at the Governor's "universal acquirements," his art of fighting by proclamation, his disposition to experiment in political as well as mechanical matters, his obsession with economy. Young Irving remarked that if William had been less learned he might

23 National Intelligencer, July 19-Oct. 6, 1809. Smith himself was presumed to have written the articles.

24 James Cheetham in American Citizen, quoted by Charleston Courier, Sept. 20, 1809.

25 Quoted by Charleston Courier, Dec. 21, 1809.

26 Book IV.

have been a greater governor. As for economy, Knickerbocker said: "This all-potent word, which served as his touchstone in politics, at once explains the whole system of proclamations, protests, empty threats, windmills, trumpeters, and paper war." 27 There was truth in these jests, though certainly not the whole truth, and the downfall of the prototype of William the Testy was properly attributed to the Yankees, who, in this ingenious narrative, could be regarded as either the New Englanders (with whom the New Amsterdamers were in perpetual dispute) or as the British violators of American rights.

That Jefferson was not unresponsive to humorous writing is suggested by his admiration of Laurence Sterne and his liking for Tristram Shandy, but there seems to be no way of knowing what he thought of this post-presidential satire on himself. He does not appear to have owned or ever to have referred to Knickerbocker's History.

Ill

About the time of his retirement Jefferson had Samuel Harrison Smith of the National Intelligencer print a circular letter laying down for himself the law of never interfering with his successor or the heads of departments in any application for public office. 28 He was never quite able to live up to his resolution, but his chief departures from it were shortly before and during the War of 1812, when he was especially pressed to intervene. In the first half of Madison's first term, however, he gave significant counsel and rendered important services in connection with personnel and appointments at the highest level. In particular the reference is to James Monroe a nd A lbert Gallatin. N^