EXAMPLE 1

To start with, the preceding analysis must be confirmed by taking the example of one of the best-known signed philosophical concepts, that of the Cartesian cogito, Descartes’s l: a concept of self. This concept has three components—doubting, thinking, and being (although this does not mean that every concept must be triple). The complete statement of the concept qua multiplicity is “I think ‘therefore’ I am” or, more completely, “Myself who doubts, I think, I am, I am a thinking thing.” According to Descartes the cogito is the always-renewed event of thought.

The Parmenides shows the extent to which Plato is master of the concept. The One has two components (being and nonbeing), phases of components (the One superior to being, equal to being, inferior to being; the One superior to nonbeing, equal to nonbeing), and zones of indiscernibility (in relation to itself, in relation to others). It is a model concept.

But is not the One prior to every concept? This is where Plato teaches the opposite of what he does: he creates concepts but needs to set them up as representing the uncreated that precedes them. He puts time into the concept, but it is a time that must be Anterior. He constructs the concept but as something that attests to the preexistence of an objectality [objectité], in the form of a difference of time capable of measuring the distance or closeness of the concept’s possible constructor. Thus, on the Platonic plane, truth is posed as presupposition, as already there. This is the Idea. In the Platonic concept of the Idea, first takes on a precise sense, very different from the meaning it will have in Descartes: it is that which objectively possesses a pure quality, or which is not something other than what it is. Only Justice is just, only Courage courageous, such are Ideas, and there is an Idea of mother if there is a mother who is not something other than a mother (who would not have been a daughter), or of hair which is not something other than hair (not silicon as well). Things, on the contrary, are understood as always being something other than what they are. At best, therefore, they only possess quality in a secondary way, they can only lay claim to quality, and only to the degree that they participate in the Idea. Thus the concept of Idea has the following components: the quality possessed or to be possessed; the Idea that possesses it first, as unparticipable; that which lays claim to the quality and can only possess it second, third, fourth; and the Idea participated in, which judges the claims—the Father, a double of the father, the daughter and the suitors, we might say. These are the intensive ordinates of the Idea: a claim will be justified only through a neighborhood, a greater or lesser proximity it “has had” in relation to the Idea, in the survey of an always necessarily anterior time. Time in this form of anteriority belongs to the concept; it is like its zone. Certainly, the cogito cannot germinate on this Greek plane, this Platonic soil. So long as the préexistence of the Idea remains (even in the Christian form of archetypes in God’s understanding), the cogito could be prepared but not fully accomplished. For Descartes to create this concept, the meaning of “first” must undergo a remarkable change, take on a subjective meaning; and all difference of time between the idea and the soul that forms it as subject must be annulled (hence the importance of Descartes’s point against reminiscence, in which he says that innate ideas do not exist “before” but “at the same time” as the soul). It will be necessary to arrive at an instantaneity of the concept and for God to create even truths. The claim must change qualitatively: the suitor no longer receives the daughter from the father but owes her hand only to his own chivalric prowess—to his own method. Whether Malebranche can reactivate Platonic components on an authentically Cartesian plane, and at what cost, should be analyzed from this point of view. But we only wanted to show that a concept always has components that can prevent the appearance of another concept or, on the contrary, that can themselves appear only at the cost of the disappearance of other concepts. However, a concept is never valued by reference to what it prevents: it is valued for its incomparable position and its own creation.

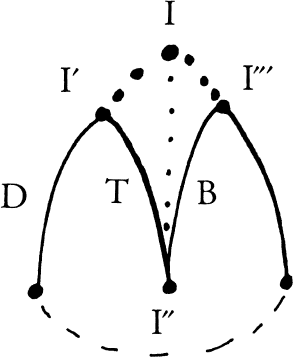

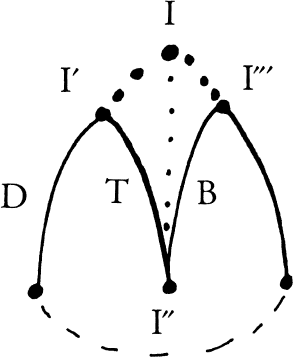

Suppose a component is added to a concept: the concept will probably break up or undergo a complete change involving, perhaps, another plane—at any rate, other problems. This is what happens with the Kantian cogito. No doubt Kant constructs a “transcendental” plane that renders doubt useless and changes the nature of the presuppositions once again. But it is by virtue of this very plane that he can declare that if the “I think” is a determination that, as such, implies an undetermined existence (“I am”), we still do not know how this undetermined comes to be determinable and hence in what form it appears as determined. Kant therefore “criticizes” Descartes for having said, “I am a thinking substance,” because nothing warrants such a claim of the “I.” Kant demands the introduction of a new component into the cogito, the one Descartes repressed—time. For it is only in time that my undetermined existence is determinable. But I am only determined in time as a passive and phenomenal self, an always affectable, modifiable, and variable self. The cogito now presents four components: I think, and as such I am active; I have an existence; this existence is only determinable in time as a passive self; I am therefore determined as a passive self that necessarily represents its own thinking activity to itself as an Other (Autre) that affects it. This is not another subject but rather the subject who becomes an other. Is this the path of a conversion of the self to the other person? A preparation for “I is an other”? A new syntax, with other ordinates, with other zones of indiscernibility, secured first by the schema and then by the affection of self by self [soi par soi], makes the “I” and the “Self” inseparable.

The fact that Kant “criticizes” Descartes means only that he sets up a plane and constructs a problem that could not be occupied or completed by the Cartesian cogito. Descartes created the cogito as concept, but by expelling time as form of anteriority, so as to make it a simple mode of succession referring to continuous creation. Kant reintroduces time into the cogito, but it is a completely different time from that of Platonic anteriority. This is the creation of a concept. He makes time a component of a new cogito, but on condition of providing in turn a new concept of time: time becomes form of interiority with three components—succession, but also simultaneity and permanence. This again implies a new concept of space that can no longer be defined by simple simultaneity and becomes form of exteriority. Space, time, and “I think” are three original concepts linked by bridges that are also junctions—a blast of original concepts. The history of philosophy means that we evaluate not only the historical novelty of the concepts created by a philosopher but also the power of their becoming when they pass into one another.