CHAPTER 13

Dissonance

Dissonance is the word we use to describe unpleasant combinations of notes. There are two sorts of dissonance in music. One type, sensory dissonance, is based on the science of how your hearing system works. Musical dissonance, by contrast, is more concerned with your musical taste. These are completely different concepts, so let’s look at them separately.

Sensory dissonance

We don’t fully understand how sensory dissonance works yet, but we do know that unlike musical dissonance, it’s not a matter of subjective opinion; it’s a feature of how your hearing system and your brain register sound. Neuroscientist Anne Blood and her colleagues at McGill University have shown that activity in an area of the brain that is associated with unpleasant emotions (the parahippocampal gyrus) increases with increasing levels of sensory dissonance.1 Basically, sensory dissonance is a biological effect that makes us experience certain combinations of notes as unpleasant. From the day we are born (and perhaps earlier), we have a general preference for consonant (non-dissonant) combinations of notes.2 Even baby chicks have been found to prefer consonance to dissonance.3

Although we can learn to enjoy a certain amount of sensory dissonance because it adds spice to music, we don’t lose the ability to distinguish between consonance and dissonance. People become indifferent to sensory dissonance only if the appropriate part of the brain (the parahippocampal cortex) is damaged.4

When your eardrum vibrates in response to a musical note, it passes the vibration on to a part of your inner ear called the cochlea. This cunning device sorts out the notes in the same way that a shop assistant sorts out the jackets on a clothes rack. Jackets are placed in order of ascending size—and the notes are organized in order of increasing frequency. The fine details of how this is achieved are, to put it bluntly, completely beyond me, but thankfully we only need to know the basics.

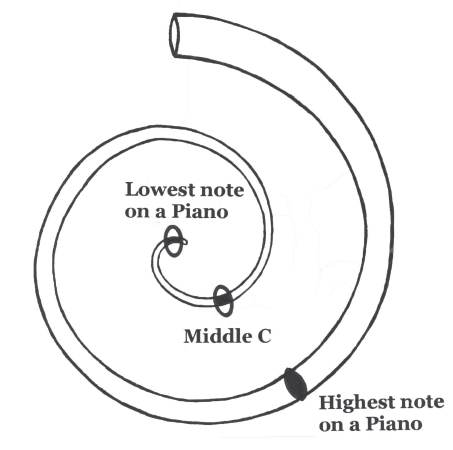

The cochlea is a small, coiled tube, and vibrations passed on from the eardrum enter it at one end. If you listen to a single note with a certain frequency, the vibrations will travel into the tube, causing excitement among some of the tiny hairs on its inner surface. Each frequency of vibration is linked to a particular place somewhere along the length of the tube. The note you hear will have not much effect on the tube in general but will make the hairs dance like crazy in a particular area. The dancing hairs then send off a message to the brain saying, “Our frequency has arrived—hurrah!” The brain recognizes which group of hairs is involved and gets the message that we are listening to a note of a certain frequency. Very-high-frequency notes find their dancing hairs just inside the entrance to the tube. Bass notes find theirs down toward the other end—as you can see in this sketch:

This all works very well unless the notes are too close together in frequency. Each frequency excites a little patch of hairs, and if the patches are clearly separated, then the brain can make sense of it all. If, however, the patches overlap a bit, the brain becomes confused and unhappy.

One way of demonstrating this confusion and unhappiness is to use another of your senses—your eyesight.

Have a look at this:

This image is made up of two overlapping words and it’s very difficult to recognize which words are involved. If the words are printed side by side, though, without any overlap, they become easy to read:

And if they are printed with almost complete overlap, it’s fairly easy to work out what the print says:

So, somewhere between almost complete overlap and no overlap at all, your vision system can be confused and made to work hard trying to untangle what it’s looking at.

The same sort of thing happens with your hearing system. If two simultaneous notes are very close together in frequency, the brain recognizes only one (slightly expanded) patch of dancing hairs and therefore one note. If the patches are clearly separated, then the brain recognizes two notes. Somewhere between these two extremes the combination of partially overlapping frequencies sounds dissonant, just as the partially overlapped words we saw earlier were the most difficult to read.

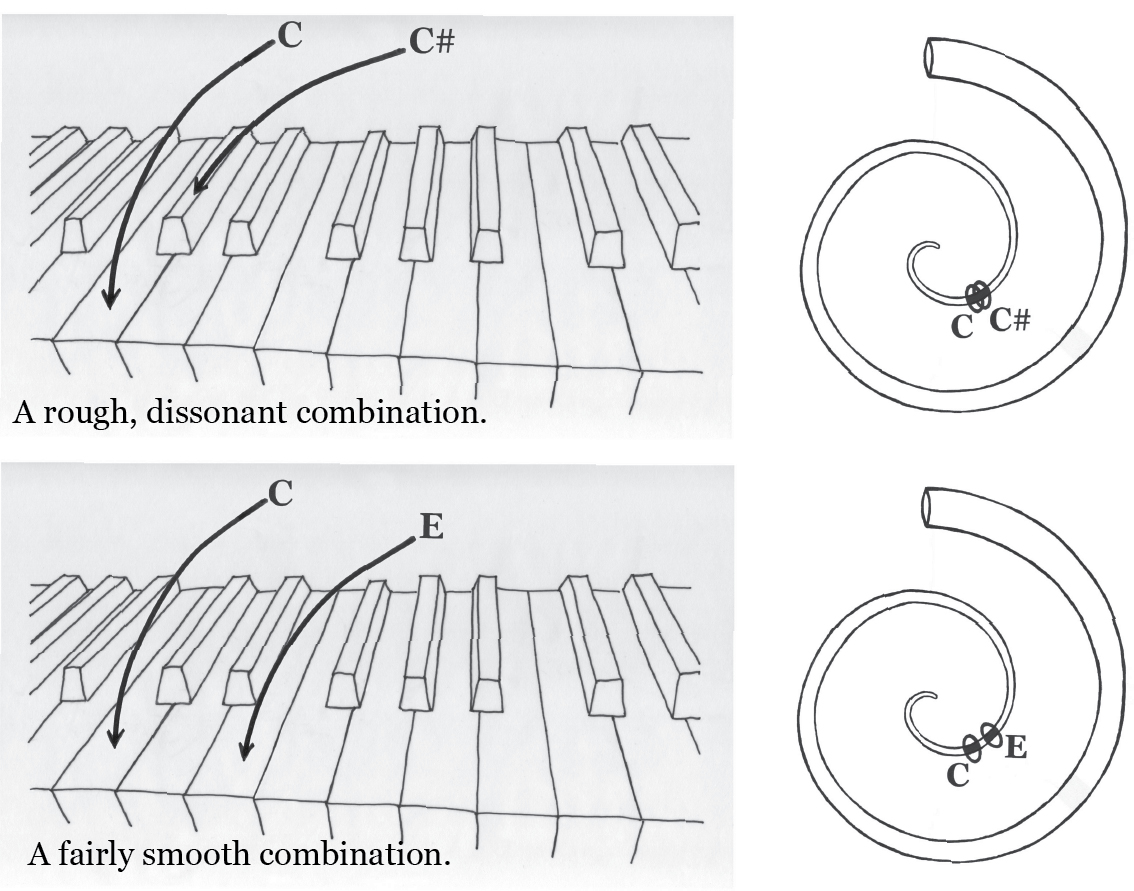

This is why, if you press down any key near the middle of a piano keyboard and the key next to it, you hear a jarring, dissonant sound. Notes a semitone apart played together make for a rough, tense combination wherever you are on a piano keyboard because their frequencies partially overlap on the cochlea.

If you play notes two semitones apart, the notes still sound fairly dissonant. When the distance between the notes is three or four semitones, everything starts to sound more pleasant and relaxed. But that’s true only on the right-hand half of the piano, where the mid-range to high notes are.

Down on the left-hand, bass half of the keyboard, things get tricky. The patches of dancing hairs that respond to low notes are closer together than the ones for high notes—so nearby notes are more likely to overlap. As we move downwards in pitch, notes need to be farther and farther apart before they sound agreeable. Down in the deep bass section of the piano, even normally harmonious, large intervals sound rather dissonant. (I use the term “rather dissonant” here because sensory dissonance isn’t an on or off thing; it’s more like a sliding scale from “very dissonant” to “consonant.”)

Down at the bass end of a keyboard, notes a surprisingly long way apart overlap on the cochlea. Even the combination shown here (seven semitones, where the upper note has a cycle time that’s ⅔ of the cycle time of the lower note) will be rather dissonant.

Composers, songwriters, and arrangers may not know the scientific details of why harmonies sound poor for bass instruments if the notes are anywhere near each other, but they can hear that it happens, which is why they write chords and harmonies with big gaps between the notes for bass instruments. This phenomenon also explains why chords that sound clear and harmonious on a standard guitar sound far less so on a bass guitar: your brain can’t distinguish the low notes from one another clearly, so everything sounds woolly and dissonant—which is why most bass players don’t play chords.

As I said earlier, we don’t fully understand sensory dissonance yet, and although this “overlap on the cochlea” theory provides a good general description of what’s going on, scientists are still busy at work on the subject.

But let’s not forget that sensory dissonance isn’t necessarily a bad thing in music. If we add a dissonant note to a chord, we get a tense sound that needs to be relaxed sometime soon. A lot of music uses this effect to build a cycle of tension and release that adds motion and interest to a piece. Without the occasional use of dissonance, music would be bland and far less effective at stirring our emotions. So in spite of the fact that we begin life with an aversion to sensory dissonance, we can grow to appreciate and enjoy it.

Musical dissonance

Rather than being based on biology (like sensory dissonance), musical dissonance is generally a matter of taste. How edgy do you like your harmonies or melodies or rhythms to be? Do you like everything to be ordered, relaxed, and musically consonant, or do you like your music to be spicy, risky, and musically dissonant? How much do you enjoy unfamiliar types of music?

Musical dissonance sometimes includes some sensory dissonance (e.g., spiky jazz chords involving notes a semitone apart), but that’s not necessarily the case. For example, if a songwriter or composer writes something soothing in the key of B major and suddenly interjects an F major chord, the event is musically dissonant*—even though the F major chord itself is consonant. The chord hasn’t caused any confusion in your cochlea. It’s just that you weren’t expecting it.

Basically, we call a piece of music musically dissonant if it’s outside our comfort zone.