TO KATHMANDU

One day, in the year 2000, I was asked to write a book, a small one, about any place in the world I wished and doing something in that place I liked doing. I answered immediately that I would like to go hunting in southwestern China for seeds, which would eventually become flower-bearing shrubs and trees and herbaceous perennials in my garden. Two years before, in 1998, I had done this. I had accompanied the most outstanding American plantsman among his peers, my friend Daniel Hinkley, and some other plantsmen and botanists on a plant-hunting and seed-collecting adventure in Yunnan and Sichuan Provinces. I started out in the city of Kunming and it was so hot—I wondered if I was just going to have a look at things I could grow in a garden that I made on the island in the Caribbean where I grew up. I wondered if the most thrilling moment I would remember was seeing the tropical version of Liriodendron tulipifera, the tulip tree, of William Bartram’s travels. But then we went out in the countryside, and up into the mountains, up to fourteen thousand feet in altitude, Dan now reminds me, and I collected seeds of species of primulas, Iris, juniper, roses, paeony, Spiraea, Cotoneaster, Viburnum, some of which I have now growing in my garden.

I experienced many difficulties in this adventure, but they were of a luxurious kind. I did not like, and could not even bring myself to understand, my hosts’ relationship to food: I feel that the place in which it is taken in, eaten, be it the kitchen or the dining room, must be far removed from the place, bathroom or outhouse, in which it comes out again in the form of that thing called excrement. Not once was my life really in danger, not even when I was close by to places where the Yangtze River was in the process of flooding over its banks just at the moment I was driving by its banks in my rather nice, comfortable bus. The greatest difficulty I experienced was that I often could not remember who I was and what I was about in my life when I was not there in southwestern China. I suppose I felt that thing called alienated, but it was so pleasant, so interesting, so dreamily irritating to be so far away from everything I had known.

And so when I was asked to do something I liked doing, anywhere in the world, my experience in southwestern China immediately came to mind. I called up Dan Hinkley and I said to him, Let’s go to China again. As a plantsman and botanist, and nurseryman to boot, Dan goes to some faraway place and collects the seeds of plants once or twice a year. The intellectual curiosity of the plantsman and botanist needs it, and the commercial enterprise of the nurseryman needs it also. When I suggested southwestern China to him as a place of adventurous plant-collecting, he said, Oh, why don’t we do something really exciting, why don’t we go to Nepal on a trek and look for some Meconopsis? Why don’t we do something really interesting, he said.

In October 1995, Dan had traveled to Nepal on his first seed-collecting expedition there. He had collected in the Milke Danda forest, a forest that is in the Jaljale Himal region. Milke Danda, Jaljale Himal! To see those words on a page, flowing from my pen now, is very pleasing to me. In 1998 when I accompanied Dan and some other plants-people to southwestern China, I had no idea that places in the world could provide for me this particular kind of pleasure; that just to say the name of a place, to say softly the name of a place, could cause me to long deeply to be in that place again, or to long just to be nearby again. That first visit he made to Nepal haunted Dan so that he wanted to go there again. It’s quite possible that I could hear his longing and the haunting in his voice when he suggested to me that we go looking for seeds in the Himalaya, but I cannot remember it now. And so Nepal it was.

We were all set to go in October 2001. Starting in the spring of that year, I began to run almost every day because Dan had said that the trip would be arduous, that I had no idea how hard it would be, and that I must prepare my body for the taxing physical test to which I would subject it. And so I ran for miles and miles, and then I lifted weights in a way designed to strengthen the muscles in my legs. It was recommended to me that I walk with a backpack full of stones, so that I might make my upper body more strong. I did that. And Dan had said that I needed a new pair of boots and that I should break them in, and so I wore them all the time, in the garden, to the store, or even to a dinner outing. Everything was going along well, until near the end of August: I suddenly remembered that my passport with a visa stamped in it from the Royal Nepalese Consulate General in New York had not come back from my travel agent. I called to tell her that she ought to hurry them up because I applied for my visa in June and here it was August, and still I had not heard if I would be allowed to enter that country in a month. She was very surprised to hear from me, she had not received my passport in June, she had forgotten all about me. In any case where was my passport? We could trace its arrival in her office on Park Avenue, but it never reached her desk. It has been lost, she said; it has been stolen by someone in her office, I thought.

I applied for and within a matter of days received a new passport; I applied for and within a matter of days received a visa to enter and exit Nepal. I had myself inoculated against diseases for which I had not known antidotes existed (rabies) and against diseases I had not known existed (Japanese encephalitis). I felt all ready to go and then there came that new State of Existence into being called “The Events of September 11.” How grateful I finally am to the uniquely American capability for reducing many things to an abbreviation, for in writing these words, The Events of September 11, I need not offer a proper explanation, a detailed explanation of why I made this journey one year later.

The following spring, the spring of 2002, I resumed my intense training. I trained so hard that near the end of June I was limping, I had done something to my right foot, something that did not show up on an X-ray, only my foot hurt so very much. Then for a short period of time, my son, Harold, who was thirteen at the time, and I determined that he too would make the trip, yes, he would go to Nepal with me, but by the end of August we could see that was not to be. Dan sent me an e-mail asking for our passport numbers and other documents; he wanted to forward them to our guides who would then secure for us our internal travel documents. At that moment Harold said, No, he would not go, as if the whole idea was ludicrous in the first place. Later I would have many opportunities to be glad for his decision. I wrote back to Dan: “So sorry about all this. Harold is not coming but you probably guessed that. Tickets and documents only for me, then. We will share a tent. By the way: Have you heard of the plane crashing and the bus going off the road in the floods, all in Nepal? This happened yesterday. My love to you and Bob.”

Just around then, Dan’s friends, two botanists who are married to each other and own a very prestigious and famous nursery in Wales, where they live, decided to join us. I have always been so envious of the many seed-collecting trips Dan had made with them to Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and China. Their names are Bleddyn and Sue Wynn-Jones, and the number of times I have heard Dan say that he and Bleddyn and Sue collected something together would fill me with such envy because I really always want to be someplace where seeds are being collected, I want to be in the place where the garden is coming into being. Their presence made me happy and when Dan said, in one of his e-mails, “This is going to be an adventure,” it made me forget, for a flash of time, the trouble I was having leaving. This account of a walk I took while gathering seeds of flowering plants in the foothills of the Himalaya can have its origins in my love of the garden, my childhood love of botany and geography, my love of feeling isolated, of imagining myself all alone in the world and everything unfamiliar, or the familiar being strange, my love of being afraid but at the same time not letting my fear stand in the way, my love of things that are far away, but things I have no desire to possess.

I left my home in the mountains of Vermont at dawn one morning at the beginning of October. Nothing was out of place. I made note that the leaves were late in turning, but when I look at a record I keep of things as they occur in the garden I see that I always think the leaves are late turning. It was warm for an early morning in early October, but it is so often warm in early morning in early October. And yet as I drove away from my house, I had the strange sensation that I might be seeing everything in the way I was seeing it for the last time, that when I saw again those things that I was looking at that morning, the mountains (the one I can see from my house, Mount Anthony, in particular), the trees, the houses, the people in their cars, the very road itself, they would not look the same, that the experience I was about to have would haunt many things in my life for a long while afterward, if not forever.

It was only after I returned home a month later that I noticed how quiet and clear are the streams and rivers near where I live; how calmly they meander along as if their paths are old and dull, their origins nearby, not hidden deep within some still unfamiliar place beneath the surface of the earth. Only then I noticed too how smoothed out the sides of the mountains were, not rippling with ridges; how almost uniform in height they seemed, gentle slopes, soft peaks, old and known, with no parts of them unexplored. And the sky above all this? Again, only when I returned home did I notice that the sky above me hardly ever caused me to observe it with real anxiety, being mostly clear and a sad pale blue in the daytime and turning to a grayish black at night. If I made particular note of water, land, and sky when I returned home, it is only because when I was away, walking in the foothills of the Himalaya, that became the world I knew. I knew with certainty. There, I lived outside all that time; and the distinctiveness of it all, the wide and open spaces, were especially so when seen from far away and protected by an overarching and concavelike sky. And this wide-open space was then pursued by the unrelenting encroachment of the mountains, this landscape in the Himalaya.

I left my home on a morning in early October and headed to the airport, which was four hours away. At the time, feeling that it was ridiculously false and then again not so at all, I insisted to myself that everything I saw I was seeing for the last time. This turned out to be true, for when I saw all that I had been familiar with again, everything was changed in my eyes, and yet it did remain the way it had always been, only that I did not see anything the same way again.

I left my home, I went to an airport in New York. I arrived there in the middle of the day. The airport seemed deserted, or spare of human emotion, or just unsettling in a chemically induced way, but I had not ingested a chemical of an unusual kind, as far as I knew. I got on the airplane. All the time my state of mind was influenced by the hard fact that my thirteen-year-old son had not wanted me to go away. That he had said goodbye to me with tears rolling down his cheeks; that he had, days before, asked people he thought could influence me, to tell me outright, my going away to this place, for such a long time, would cause him to suffer. I love my children, more than I love myself, and yet there I was on an airplane off to Hong Kong and then to Nepal.

On the way to Kathmandu, I spent less than twenty-four hours in Hong Kong; and this small amount of time had the feeling of being a particle of some sediment in a bottle that was being shaken up. Oh, the whirl of it. I was not here or there or anywhere. I was at the airport, again, and the flight was eight hours late. I was sent to a part of the airport where people with destinations different from mine were waiting. A modern airport is not unfamiliar to me. I have been in one of them many times, waiting to go from one place or the other. In a modern airport you will suddenly be confronted with people who are very different from you even though you are all wearing the same sort of clothes, and who have very different ideas from you about how the very world in which you place step after step ought to be arranged. I am used to that. But even so in Hong Kong, in the airport, I felt strange: alone, lonely, excited, happy, afraid, despair, all at the same time. These feelings were exaggerated when I got on the plane, Royal Air Nepal, and was told that the time was not an hour ahead, or an hour behind, but that the time was measured by the quarter hour. It meant that while I could calculate the rest of the world based on that thing called the hour being behind or ahead of me, when I was in Nepal fifteen minutes was lost or gained one way or the other. How confusing is such a thing, how magical is such a thing, how correct is such a thing. Though I only know all of this in retrospect, in sitting at my desk in Vermont and thinking about it, in looking back. We flew to Kathmandu in the dark of night. I childishly asked if it was safe to do so, wondering if we might accidentally crash into a mountain. We landed safely and I gave a man forty American dollars for carrying my suitcase from the baggage area to the taxi. Everyone was astonished by this amount of money, but I was so grateful to be myself, whatever that was, in one place that I would have paid many times that more just to say, “Hi, I am me.” I went to bed and slept soundly through the night in a memorable hotel called the Norbu Linka, memorable because it is the only place I have slept in Kathmandu.

That next morning Dan took me to have my photograph taken for my trekking visa, which is a separate one from my visa to enter Nepal, and he also took me to a store to buy an elegant walking stick, a walking cane made of native wood that had the head of a dog carved at the top, just where your hand gripped it. At another store, we bought chocolate bars and tins of candy. Then we went to the best bookstore in the world—that is if you are interested in the world of exploration—the Pilgrims Book House, and I bought a book, just for the sake of buying a book, about the first attempt to climb Kanchenjunga. Until that moment I did not know there was a mountain called Kanchenjunga. All that time, I was still in between the things I had left behind in Vermont, my thirteen-year-old son not wanting his mother to go so far away from him, the flat-top mountains, the certainty of, just for instance, the plumbing situation (here is the kitchen, here is the bathroom, the two do not know the other exist). Dan had been in Kathmandu for some days before me and he had sent me an e-mail in which he said it was very hot, so bring suitable clothes. Many days before that he had sent me a long list of suitable clothes I would need for our walk in the mountains where we would gather seeds. This particular e-mail made me bristle with anxiety, but anxiety is never any help at all, and so I took note of it and then ignored it. Dan had titled his e-mail “I’ll do your bras if you do my underwear,” and he’d written:

Hi Jams: I am at Sea-Tac—no turning back now. I have thought through the trip endlessly and hope I have bases covered for us. Just a reminder of a few things … Make sure you water seal your boots and make sure you bring two pairs—I am taking one low-top and one high-top. The boots will get soaked eventually, but the more you have them water sealed, the better. I like to do them twice beforehand; put them in the sun and let the leather take on the seal, and then do it one more time. I am bringing extra seal with me for us to use during the trip but this needs to be done now.

The socks are important. Buy polypro liners and then polypro hiking socks. The liners will help wick the water away, both from sweat as well as if we start hiking in the morning with wet feet (there is nothing more rude than putting on cold, wet, stiff, hiking boots). I am taking detergent along and we can do some light laundry washing occasionally. (I’ll do your bras if you do my underwear.) I am only traveling with three pairs of underwear—in addition to:

–two pairs of polypro long johns, tops and bottoms

–three polypro t-shirts

–two light weight pants, one which converts to shorts

–one pair of hiking shorts

–six pairs of socks and six pairs of sock liners

–one good pair of gloves and five pairs of lightweight glove liners (these are good as they are comfortable to wear during the chilly days without having to wear gloves)

–one wool sweater

–one down vest

–rain parka and rain pants

–one long-sleeved soft fleece jacket to wear in the camp at night

–a warm pair of camp pants—comfy insulated pants that I will only wear at night. I will sleep in my long johns.

–Come up with a suit of clothes that you will only wear at the end of the day after hiking is over; it is rather nice to change into something that is basically clean, warm, and dry.

–I bought a good insulated sleeping-bag pad. This is important—do not buy an inflatable one. This will keep you warmer and more comfortable than anything else.

–two water bottles—important

–two pairs of sunglasses in case one is broken or lost—absolutely necessary to have these as we will be in snow in full sun.

I have brought three courses of Cipro and I suggest you get your doctor to give you three as well—I am also going to take Pepto-Bismol tabs in Kathmandu as sort of a prophylactic—they say it works. If we get food poisoning, it will be in Kathmandu—we will be perfectly fine while on the trail as long as we only drink boiled water. Damn—I forgot to bring along iodine tablets for water purification. Would you please pick up a bottle for us? I might be able to buy in Kathmandu but not sure. Generally we don’t need them, however, during the beginning of the trek and again at the end, it is HOT hiking and at least I go through gallons of drinking water a day.

As I mentioned before, get a prescription for altitude sickness—they will know which it is. We are destined to sleep poorly when we get that high—but at least we will have each other to talk to during the night. I experience this really awful oxygen deprivation/panic attack thing for the first few nights above 10,000 feet. The drugs really help that.

I have brought plenty of foot dressing, blister treatment, so you don’t have to bother with that.

I still do not have your flight details and they will need this in order to meet you at the airport in Kathmandu. I hope we can fly together home—at least to Bangkok—and go out for some luxurious feast to celebrate the end of this experience. I arrive in Bangkok on the 3rd and leave for home on the 5th.

You will need money only in Kathmandu and in transit for meals and lodging (easily we can live for $50/day, I think). I cannot recall if our hotel, the Norbu Linka, takes credit cards or not. Kathmandu is fun, and fun for shopping too—We will have such a good time there together.

Sue and Bleddyn in full swing of training for this—taking six-mile mountain hikes every day, it sounds. Sue will not be in great shape for this, but you two will get along quite well. She is a dear and a trouper. Bleddyn is the one that dove off the cliff after Jennifer when she fell in 1995. He will be very good to have along for us both.

This is going to be so fun Jams—an experience that we will never forget and you will tell your grandchildren … (There are none yet, are there?)

Much love—my best to Harold and Annie. I am sorry that Harold is not coming along but it will happen next time, yes?

Dan

I had faithfully gone to a store nearby that sells just these sort of clothes, clothes for people who are going mountain climbing or hiking, or just generally going to spend time outdoors for the sheer pleasure of it. I bought everything on Dan’s list, though not in the quantities he recommended (more underwear, less socks, sock liners, and glove liners).

My hotel was in that area of Kathmandu called the Thamel District. It is a special area, like a little village separate from the rest of the city. It is filled with shops and restaurants and native European people, who look poor, dirty, and bedraggled. But this is a look of luxury really, for these people are travelers, at any minute they can get up and go home. I had read so much about European travelers in Kathmandu, none of it leaving a good impression; seeing these people then in that place did not make me think I ought to change my mind. Of course, I was traveling with Dan, who is of European descent, but Dan had a real purpose for being in Kathmandu: he is a plantsman, and a gardener, and such a person needs plants. There are many plants worthy of being in a garden in Nepal; Kathmandu is the capital of Nepal.

But to think of Kathmandu again: when I suddenly was in the middle of that part of it, the Thamel, I was reminded of feelings I had when I was a child, of going to something called “the fair,” something beyond the every day, something that would end when I was not asleep, when I was not in a dream. I did truly feel as if I was in the unreal, the magical, extraordinary. People seemed as if they had no purpose to being themselves, as if the only reason to be there was just to be there. The tiny streets came to an end abruptly, going immediately from the confusion of authentic and imposter to the solidly real, and the real was always poor and deprived and self-contained. Just outside the window of my hotel was an area enclosed by concrete, of perhaps forty feet by forty feet. It had pipes, with water constantly pouring out of them—it was a communal place for doing things that required water. People were bathing, washing their clothes, or filling up utensils with water. Because of my own particular history, every person I saw in this situation seemed familiar to me. But then again, because of my own particular history, every person I saw in the Thamel was familiar also. The person in the restaurant complaining about the lack of some luxury was familiar, the person at the public baths longing for luxuries of every kind was familiar, the person confused and in a quandary was familiar.

On the night of that first day I spent in Kathmandu, we ate dinner at a Thai restaurant. I cannot now remember what I ate. I did notice that my companions, Dan and Sue and Bleddyn, seemed especially kind and gentle toward me. I thought then that it was because I kept looking up for bats; I am very afraid of them. In Roy Lancaster’s book about his travels in Nepal, he mentions the fruit bats in Kathmandu, saying that they look like weathered prunes, and the idea that bats could look like something to eat was unsettling. I had not seen the fruit bats in any tree so far, and so while sitting at dinner, since we were outside, I kept looking out for them. I thought I would see them swooping around in the deep blue-black night air, hoping to realize the sole purpose of their existence: settling into my hair. But I never saw them, not even one. My companions’ kind concern toward me was because going back and forth in back of me was a very busy other kind of mammal, a rat. Eventually, I saw it, and I freaked out but only a little. I made a tiny squeal, I shuddered a little bit, but it was as if instinctively things were immediately being put in perspective: what is a lone rat scurrying in a small restaurant in a crowded city next to a small village situated in the foothills of the Himalaya full of Maoist guerrillas with guns?

I awoke the next morning to the sounds of the Himalayan crow crowing outside. It is a beautiful bird, black-feathered like the crows I am used to seeing but with a broadish band of gray around its neck. This band of gray is more like a decorative belt than a necklace, and it makes the crow seem less menacing, more friendly, as if it is not capable of the devious cunning of the crows I am used to seeing here in North America. And when seen from afar, a large number of them grouped together winging their way toward some unknown-to-me destination, they looked like a thin, worn, ragged piece of darkened cloth adrift.

I went to breakfast and ate something with curry and mango and bananas, doing this with a feeling of getting into the local spirit of things. The king had dismissed Parliament, and I wondered how that would affect our trip, for the king’s dismissing Parliament had something to do with the Maoist guerrillas, and I was going into the countryside where the Maoist guerrillas might be, and since they couldn’t kill the king would they kill me instead? What was I doing in a world in which king and Maoists were in mortal conflict? The irony of me getting into the local spirit of things was not lost on me, but this feeling of estrangement was soon replaced altogether with a sense of being lost in amazement and wonder and awe. From time to time I lost a sense of who I was, what I thought myself to be, what I knew to be my own true self, but this did not make me panic or become full of fear. I only viewed everything I came upon with complete acceptance, as if I expected there to be no border between myself and what I was seeing before me, no border between myself and my day-to-day existence. My tent, for instance: I loved my tent and would have probably died for it, and am now so glad things never came to that.

After breakfast, I sorted out my luggage, putting away my traveling clothes and shoes and jewelry in a plastic bag, leaving them with the hotel for safekeeping. All four of us had to do this, and this little event suddenly filled us with the excitement of what we were about to do. There was a lot of running up and down the hallway, into each other’s rooms, and asking questions about who had what and did they have enough of it. A last-minute run to a bank, for me, and finding it closed; running to another one and finding it also closed, but it had a cash machine. I was told I needed a certain amount of money so that, at the end of our journey, I would be able to tip the porters and Sherpas properly. And then I was with my companions and our Sherpa guide, a man named Sunam, in a little bus heading toward the airport. On our way to the airport we passed by the Royal Palace, where the king and his family live, and I should have been properly interested in that, but I was not at all. Along the palace walls are some enormous trees, junipers, and in them were fruit bats hanging upside down and asleep. I so badly wanted to see them. I craned my neck out the window, looking up as the bus in a swift crawl passed by, but I could not see them. They were there; everyone, even the driver, could see them, but I could not. Dan would say, “There’s some, there’s some,” but my poor eyes, influenced by a combination of the anxiety, wonder, and strange happiness that I was feeling, could not see the fruit bats. We boarded an airplane that made my anxiety dominate all the other feelings. It resembled something my children would play with in the bathtub, rounded and dullishly smoothed, like an old-fashioned view of the way things will look in the old-fashioned future, not pointed and harshly shiny like the future I am used to living in now.

And so we left Kathmandu and flew to Tumlingtar, a village in the Arun River valley. We were not long in the air when the scene changed from crowded city to high green hills. I would have called the hills mountains, but surrounding the hills, in back of the hills, were taller heights covered with snow. These hills ended in sharp, pointed peaks and they were tightly packed one against the other, and covered in what seemed to be an everlasting and inviting green. It was my first view of the geography of the Himalaya. From inside the plane it seemed to me as if we were always about to collide with these sharp green peaks; I especially thought this would be true when I saw one of the pilots reading the day’s newspaper, but when I told this to Dan, he said that the other times he flew in this part of the world, the pilots always read the newspaper and it did not seem to affect the flight in a bad way. He then showed me the Arun River, a body of water that I came to count on for many days afterward, as a friendly reference. We landed at Tumlingtar at three o’clock in the afternoon. It was ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit, and I knew without doubt that such a thing—ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit at three o’clock in the afternoon—was a normal occurrence.

The plane had seemed to drop out of the sky. I was worried about it landing, as I had been worried about it getting up into the air and staying there. It didn’t so much land as it seemed to be skidding across a field of short green grass. We alighted and I put on my backpack, got my walking stick, and walked out toward our campsite, which I could see was just beyond the area of the airport. The airport itself was occupied by soldiers, evidence of the dreaded Maoists, and they were wearing blue-colored camouflage fatigues. Why blue, and not green (for forest) or brown (for desert), did not remain a mystery for too long. In Nepal, the sky is a part of your consciousness, you look up as much as you look down. As much as I looked down to see where I should place my feet, I looked up to see the sky because so much of what happened up there determined the earth on which I stood. The sky everywhere is on the whole blue; from time to time, it deviates from that; in Nepal it deviated from that more than I was used to, and it often did so with a quickness that brought to my mind a deranged personality, or just ordinary mental instability.

What I was about to do, what I had in mind to do, what I had planned for more than a year to do, was still a mystery to me. I was on the edge of it, though. Here I was in a village in the foothills of the Himalaya. I could still remember the feeling of living in a village in the mountains of Vermont. I could remember that when I spoke, everybody I knew, everybody I was talking to, understood me quite well. I could remember the school building in my village, a nice, very big red brick building that was properly ventilated and properly heated and had all sorts of necessities and comforts, and yet I had found much fault with it and had refused to send my children to school there. I could remember the firehouse just down the hill from where I live and the kind people who volunteer their life to taking care of it and rescuing me if I should need rescuing. I could remember my house with its convenient and fantastic plumbing and water to be had any time I needed it, just by opening the tap in my fantastically equipped kitchen. I could remember my doctor, a man named Henry Lodge, who I often believe exists solely to reassure me that I am not about to drop dead from some imagined catastrophic illness. I could still remember my supermarket, The Price Chopper, overflowing with fruits and vegetables from Florida, California, or Chile, just so I could choose to buy or not buy, strawberries for instance, in summer, winter, any time I liked.

I walked into our camp, something I would do for many days to come, an hour after our plane landed. That sight of the tents and people milling around would become familiar to me. There were three tents set up, one for Sue and Bleddyn, one for Dan, and one for me. But Dan and I were appalled at spending our nights in separate tents, and so we immediately told Sunam that we wanted to sleep in the same tent and that the tent meant for one of us should become the baggage tent. Perhaps he was used to people like us, perhaps something from his own culture informed him that this was not a bad thing, perhaps he knew that there were more important things in this world than who slept in the same tent with whom; he said okay, that word exactly, “Okay,” he said.

I put my backpack inside my tent and while doing that realized that it was an inferno in there. I came out and realized it was an inferno out there. I was wearing some wonderful pedal pusher–type hiking pants—bought at a store in Vermont where all things regarding the outdoors are presented as fashionable—woolen socks, sturdy and altogether well-made boots, a T-shirt made of some microfiber or other. It would have been nice to be wearing less.

I then met my other traveling companions, the people who would make my journey through the Himalaya a pleasure. There was Cook; his real name was so difficult to pronounce, I could not do it then and I cannot do it now. There was his assistant, but we called him “Table,” and I remember him now as “Table” because he carried the table and the four chairs on which we sat for breakfast and dinner. Lunch we ate out of our laps. There was another man who assisted in the kitchen department and I could not remember his name either, but we all came to call him “I Love You,” because on the second day we were all together as a group, he overheard me saying to my son, Harold, after a long conversation on the satellite telephone, “I love you,” and when he saw me afterward, he said in a mocking way, “I love you,” and we all, Sue, Bleddyn, Dan, and I, laughed hard at this. He was a very good-looking man in any Himalayan atmosphere and light, and once, many days afterward, when we were very high up and it was very cold, he took a silk scarf he mostly wore around his neck and placed it bonnet-fashion on his head, and then tying it under his chin he looked like Judy Garland, if she had come from somewhere in Asia. But Judy Garland or no, we could never remember his real name, and always he was known as “I Love You.” Apart from Sunam, our other personal Sherpas were named Mingma and Thile. There were many other people, all attached to our party, and they were so important to my safety and general well-being but I could never remember their proper names, I could only remember the person who carried my bag, and this from looking at his face when I saw him pick up my bag in the morning. This is not at all a reflection of the relationship between power and powerless, the waiter and the diner, or anything that would resemble it. This was only a reflection of my own anxiety, my own unease, my own sense of ennui, my own personal fragility. I have never been so uncomfortable, so out of my own skin in my entire life, and yet not once did I wish to leave, not once did I regret being there.

We walked into Tumlingtar to see what it was like and also to buy something, anything. We thought, beer would do. Our camp was pitched in an almost already-harvested field of something, a non-vining bean or a legume of some kind. On the other side of the field was another set of trekkers, real trekkers, people who were going off to camp at the base camp area of Makalu, not people like us, who were only going to collect seeds of flowers. One group was from Austria but we decided to call them the Germans, because we didn’t like them from the look of them, they were so professional-looking with all kinds of hiking gear, all meant to make the act of hiking easier, I think. But we didn’t like them, and Germans seem to be the one group of people left that can not be liked just because you feel like it. The other group was from Spain. It was to them I turned when I could not make my satellite telephone work. They couldn’t make it work either. One night later, when I was especially worried about Harold, I looked hard at the telephone and saw that the antenna was loose and only needed me to snap it in place.

The main road in Tumlingtar was not like a road I was used to: paved with tar and a yellow line down the middle, it was more like a wide, well-worn path. It is a trailhead for going to Mount Everest or Makalu and so people there are quite used to seeing some of the other people in the world. They were used to seeing people who looked like Bleddyn, Sue, and Dan, people of European descent. They were not used to seeing people like me, someone of African descent, but they knew of our existence. I noticed that women in general and old people and children were very friendly and spoke to us with a smile and in a friendly way. The men did not. They looked us up and down and did not speak to us at all, only to each other about us. It was in Tumlingtar that I bought a pair of rubber flip-flops. They were stacked up, in every store we passed, all of them the same. In fact all the stores carried the same things, but I was sure that there were some differences between them that would be obvious to their regular patrons and not at all to me. We walked to the very last building in Tumlingtar and found it to be a restaurant with a patio and proper restaurant tables and chairs. We sat down and ordered beer. It was not ice cold and this was not important. From there we could see up into the hills where people were living, and the houses were surrounded by neatly terraced gardens where mostly food was growing, and we could see cows and chickens, a very familiar domestic kind of situation. It was here we met the sole schoolteacher for all the pupils who went to school in Tumlingtar and the health-care provider for all the people who needed health care in this town. The schoolteacher took us to his school and the four us felt that a good thing to do when we came back to our own overly prosperous lives would be to send money or books to him when we returned home. It was the way we felt then and the way I still feel now as I am writing this. But it only remains a feeling, a strong feeling. I have done nothing to make this something beyond my feelings. I asked the health worker what were the most common diseases to afflict people and he said headaches and fevers and accidents, so I said the word AIDS, and he said the word sometimes. It was almost dark by the time we returned to our tents. There weren’t any electric streetlights or television, or any other distraction from the warm and soft blackness of the night.

We had our dinner in the dining tent, a large blue tent inside which we could stand up, not the small sleeping tent. Inside the tent was a small collapsible table like one used for playing cards and four collapsible metal chairs. The table was covered with a nice blue tablecloth and set with eating utensils and paper napkins. The civility of this stunned me. When I saw the man whose job it was to carry the table and chairs wherever we went, I was appalled that someone had to carry this whole set of civility, especially when so many times it would have been far more comfortable to sit on the ground with our legs tucked under us. And we could not pronounce or even remember this man’s name, and that is how we came to call him “Table.” He was always among the last to leave camp because he cleaned up after us, and the first to arrive wherever we were going, to make things ready for us.

We went to bed at around nine o’clock that night, the latest we were up. There was still the excitement of the new, there was still lots of chatter and lingering. In any case, we were not tired. Dan and I lay in our tent laughing and chatting for such a long, loud time that the next day Sue and Bleddyn asked us to tell them what was so funny. It was only Dan telling me about a journey he had just made to South Africa with another botanist and how awkward it had been to observe someone who was married, and having an affair, start up yet another affair, and the unexpected arrival of the lover who was not the husband, bearing flowers and chocolates. That night too, I began reading The Kanchenjunga Adventure, Frank Smythe’s book about an attempt made to climb Kanchenjunga in 1930, a book I had bought at the Pilgrims Book House in Kathmandu. Until that moment I don’t think I had ever heard the name Kanchenjunga before. But I was drawn to it as if a spell had been cast over me; first the book and then the mountain, and all the way on my walk, there was nothing I wanted to see more. For my twenty some days I spent walking among the hills of the Himalaya, I lugged this book around; and for many days after I got back, this book was like a child’s comforter to me.

To Khandbari: Dan and Bleddyn seem to have gone over the map again and again. Should we go by the way of Jaljale Himal and the Milke Danda, more or less the way they had gone before in 1996, or should they go another way, the first three days of which would be the same as the last three days of that 1996 trip? They went back and forth, finally deciding that yes, the first three days of this trip should repeat the route of the last three days of the 1996 trip. This decision was of great importance to these two nurserymen, for a seed-collecting journey is so difficult. Every square foot of terrain must be carefully pored over so that not a single garden-worthy plant is missed, the poor collector not knowing if he will ever be able to come this way again. A true nurseryman is a gardener, a gardener is a person of all kinds, but in particular a gardener is a person who at least once in the gardening year feels the urge to possess completely at least one plant. This form of possession excludes mere buying or being one of the three people in the world who owns something that is variegated or double flowering when the norm is not. This form of possession comes from seeing something in seed on the knife-sharp edge of a precipice and collecting those seeds, and only after the seeds are in a bag realizing that for a few seconds possibly your life was in question. You can hear this form of possession in the voice of someone who will utter a sentence like this: “I saw some Codonopsis growing up there, couldn’t tell which one it was but I took seeds anyway.” That is no ordinary sentence said in an ordinary voice. The person who says such a sentence is in a complicated state of craving, for they are aware that they haven’t invented Codonopsis, but having found it in its natural growing area, a place where most people who grow Codonopsis as an ornament would shun living, they feel godlike, as if they had invented Codonopsis, as if without them no one growing Codonopsis as an ornament would do so. Dan and Bleddyn are nurserymen. Sue, of course is a nurseryman too, but she is a different kind of nurseryman. Sue was always quite happy to point out to Bleddyn and Dan a plant in seed as she walked along to our destination.

The nurserymen had decided we would follow the Arun River, spend a day going up the banks of the Barun River starting where it emptied into the Arun, then come back to the Arun leaving it behind when we turned to go toward the fabled village of Thudam.

That first morning, that very first morning after we left Kathmandu, would soon become routine: being awoken at half past five by Table, who brought us a cup of hot tea and a basin of hot water for washing up. I love to be in bed and hate getting out of it quickly, so I lingered then, and always lingered every morning after that. Dan was always first out of our tent, immediately packing up his sleeping bag and mattress, making ready his day pack; and then performing a set of calisthenics—sits-ups and push-ups, all adding up to five hundred repetitions. That first morning when I saw him stretching and twisting, it looked like such a good idea I decided to join him the next day. In the days to come my enthusiasm waxed, waned, and disappeared altogether in that order, and that quickly.

It was already hot at six o’clock in the morning. We had a delicious breakfast of omelet, oatmeal porridge with hot milk, and pancakes. The morning was beautiful, the sky was blue, not the impersonal blue of the sky that I was used to, but as if it was specially tinted that way; and even though it was a wide open sky, very big, it felt confined, as if it was more like a ceiling than a sky. And this confusing notion—sky or ceiling—only grew more so; for a sky is a part of the earth, it is the thing to which you might be exposed, the unfeeling elements raining down on you come from the sky; a ceiling, on the other hand, is the structure that protects you from the sky.

At exactly half past seven in the morning we left camp. We walked through the town of Tumlingtar, the very way we had been the afternoon before where we had met the schoolteacher and the health-care worker, but I didn’t see either of them. I didn’t see anyone from the evening before and I left the place with a feeling of theoretical sadness, for it was sad that I might never, would never, see any of these people again, or see this place again, and a final parting is a time to feel sad. And so I walked out of the village, up my first official incline. It wasn’t at all a very big one, but since I had never just walked up a hill as an everyday thing, I usually drove up a hill as an everyday occurrence, I felt challenged by it. Also, I was influenced by people’s warnings about heights and sudden exertion and Himalayan heat. I walked up the incline and thought how good to get that over with and saw that there was another incline and another incline, but then there was a leveling off, but then there were more inclines and then the heat got hot. The path we were walking on was the size of a narrow road, gouged out of the red clay. We walked up a gradual incline, the sun getting a hot I had never known. Up, up we walked, each plateau the beginning of a new, gradual ascent. By midmorning we had gained some height—I could see that—I could look back and see where we had been. But I was used to going somewhere and arriving quickly, and so had to clamp down on feeling impatient. And, there was nothing to collect, certainly nothing I could grow from this climate in the one in which I actually live. I could see Ricinus, marigold, and Datura, Cosmos, sunflowers growing in people’s gardens, and also plots of corn. Below us was the broad, flowing Arun, winding its way down to the Ganges. We passed people who seemed native to India, other people who seemed native to Nepal, and other people who seemed from somewhere in between.

I cannot tell now exactly when in those first few hours of the morning on my journey that my understanding of distances collapsed. I walked through the town of Tumlingtar and the way out led to a sharp incline and then to a set of houses surrounded by cultivated plots that seemed to be resting on a plateau, level ground, but the ground was never level for long, and suddenly, or eventually, I was climbing again, going up and up, and the going up seemed sudden, surprisingly new, for I had not expected it. For those first few hours, I was expecting the landscape to conform to the landscape with which I was familiar, gentle incline after gentle incline, culminating in a resolution of a spectacular arrangement of the final resting place of some geographical catastrophe. But this was not so. I walked up toward a ridge, and I thought that when reaching the ridge my whole being would come to something, the something that had made me there in the first place. But this was never to be so. The Himalaya destroys notions of distance and time, I thought then, plant-hunting destroys all sorts of notions, but this I have always known.

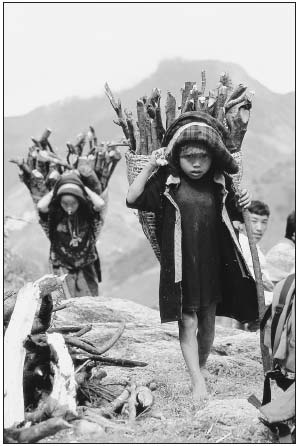

Nepalese gathering Rhododendron, their primary fuel source

The road then, sometimes as wide as a dirt driveway in Vermont, sometimes no bigger than a quarter of that, was red clay unfolding upward; the top of each climb was the bottom of another. By midmorning my senses were addled. It took me many days to realize, to accept really that I was going up; it took me many days to understand how far up up was, how there was no real up, how going up was just a way of going there. I began to have a nervous collapse, but fortunately there was no one in my company, botanist, Sherpas, and porters, to whom I could make my predicament matter. Dan had told me of the practice in Nepal of planting two Ficus trees together, Ficus benghalensis and Ficus religiosa, providing shade for the traveler, who from time to time turns out to be people like us. We passed by three such plantings and stopped to drink water, and then at the fourth one we stopped for lunch. As we walked we had been accompanied by a band of children, though not the same ones all the time. As some of them left, others would take their place. When we stopped for lunch, they crowded around and stared at us in silence. They watched us as we ate our lunch. It felt odd but also seemed fair: we were in their country looking at their landscape after all. That day, our first day of stopping to eat lunch, began with cups of hot orangeade, a drink that seemed then extravagant and unnecessary, tasting so hot and sweet, but later we would come to count on and look forward to it. According to the watch I wore on my left hand, a watch that was equipped to do all sorts of things that I could not make sense of, tell direction for one, it was ninety-six degrees and we were in the full heat of the sun all the time we walked. Sue had been walking with her umbrella open, shading herself. When in Kathmandu she had told me about bringing along an umbrella, I had secretly thought it an unnecessary thing to do; now I saw why and I could only look at her with envy.

We continued on our way that afternoon, the scenery remaining the same as the morning, except we came upon a family who lived in a small house that was in the shade of a huge citrus tree, a tree with fruits larger than grapefruits. At about half past one we came into Khandbari, a town that had telephones connected to the world from which I had just come. I called my son, Harold, spoke not to him but to someone who could say to him that I had called him, and went from feeling pleased with myself for that to feeling sad because I had not been able to tell him that I loved him myself. By that time, it was less than a week since I had been away from my home, but I began to wonder what exactly separated me from their memory of me. I was not dead, but might I as well be? Still, might-as-well is different from the certainty.

We passed through Khandbari and almost got into trouble because Dan had left his passport in Kathmandu and Khandbari had a checkpoint. I saw Sunam, our lead Sherpa and guide, speaking to a man in military uniform with an intensity and rapidity I had only seen in movies, and so had thought invented for presentation in a theatrical situation, but it worked in the same way; we were allowed to go on. We reached the place where we would spend the night, a village called Mani Bhanjyang, but the best spots had been taken by the two groups of trekkers who were on our same route. They were going to Makalu Base Camp, and we were on the same route as they for the next two days. Sunam found a place for us to camp down from that in the middle of a field, the only other level piece of earth in the vicinity. We were thirty-seven hundred feet up and even then the sky was beginning to be darker and more curved than I had ever known it to be. That night, I called Harold on my satellite phone and spoke to him directly.

It was that next morning that I began to see the flora of Nepal. We had left our campsite at half past six in the morning and started walking toward what, I did not know yet. It was ninety-six degrees by seven, according to the watch I wore, and we walked up and up for two hours straight. In fact we were just walking through, and also just walking toward, the end of our journey, but I did not know this yet. I still had the idea that we would walk to something and then leave it for something else. But that was never so. We were walking, and every place we walked was something, every place we walked was important, certainly from the point of view of a gardener. It was just that this gardener lives in Vermont. In any case we were walking, and it was very warm and I kept my eyes closed, in a way, because the climate I was walking in was not the climate in which I make a garden. The climate in which I was walking, the things growing there would count as annuals for me. As a gardener, I have a fixed view of annuals. They really are ornamentals. That is, they are ornaments for the more substantial and, so, really real perennials. In any case, we were walking and I was with Sue. For Dan and Bleddyn had raced ahead as would always be the case, and suddenly I saw these pink flowers everywhere—at my feet when I looked down and somewhat above eye level when I looked up, and then alongside me when I was just going forward. I recognized them from shape and texture, only I had seen them in another color, deep purple. I had seen those same flowers in a nursery in Vermont and in a garden in Maine but only in deep purple. To see them now in pink while remembering them in purple enhanced my feeling of anxiety and alienation, and so when I said to Sue, “What is this?” and she answered me matter-of-factly, “That’s Osbeckia,” I was comforted.

The plant I had seen in the nursery in Vermont and in my friend’s garden in Maine had a dark fleshy-colored and coarse-skin stem with deep purple flowers. I had always wanted to plant them in my garden, but they seemed as if they were not really annuals, they seemed too late-blooming and too woody in stem for my climate. On the whole, in my garden (and all the time I was walking around in Nepal I was mostly thinking of my garden) annuals need to be delicate-looking, while at the same time bearing flowers non-stop as if they do not know how to do anything else. Now as I trudged along, not knowing really where I was going, I was thinking of something I had known in passing, a plant seen in a nursery, and in a garden in Maine, trying to latch on to it as if it were one of the certainties in the whole of life. Much later I learned that the deep purple form of Osbeckia comes from Sri Lanka, the one before me was native to the place in which I was seeing it.

That day we walked eight miles going gradually uphill. We stopped for lunch in the middle of a village and I asked for a cola soft drink, and received it. That was the last time such a thing happened. It was then that I began to notice this phenomenon. I saw a girl, about the same age my daughter was then, seventeen, combing the hair of someone else with much carefulness; she was combing through her familiar’s thick head of straight hair because it was riddled with lice. This was all done with a loving fierceness, as if something important depended on it. The person combing the hair used a comb that was fine-toothed and carefully went through the hair again and again, making sections and then dividing again the sections into little sections. This engagement between the delouser and head of hair made me think of love and intimacy, for it seemed to me that the way the person removed the lice from the head of hair was an act of love in all its forms. I saw this scene over and over.

That day, for lunch, the vegetable was something I knew by the name of “christophine” and which was familiar to Sunam by another name in Nepali. It is a soft, fleshy, watery fruit originating from somewhere I do not know but is used as a vegetable by people who come from the tropical parts of the world. It is not grown in Antigua, the island in the Caribbean where I am from, but it was grown on the island of Dominica, the island my mother is from. This vegetable was a staple of her diet when she had lived there, and I was remembering the lengths to which she would go to find it and incorporate it in my diet. I hated it then, and so imagine my surprise to find it for lunch in a small village in Nepal. It was the most delicious thing I ever tasted.

From the place we ate our lunch, the center of a little village full of people and many of the things that come with them, I could see ahead of me, my way forward, a landscape of red-colored boulders arranged as if deliberate and at the same time the result of a geographic catastrophe. I was making this trip with the garden in mind to begin with; so everything I saw, I thought, How would this look in the garden? This was not the last time that I came to realize that the garden itself was a way of accommodating and making acceptable, comfortable, familiar, the wild, the strange. Above us were some large brown rocks and they seemed firmly placed. So strange, I thought, How would I get to them? I thought, Once I got to them, I thought, Life would be settled, I thought. Much to my surprise, I walked up to them and was in them, and found a place to take a pee and then walked some more into a forest of gingers (Hedychium) in flower, skullcaps in flower, Osbeckia in flower, Euphorbia in flower, Arisaema in flower—and the botanists, Dan and Bleddyn, especially were sad. They were not just sad, they began to sulk, and Dan complained to me about all that walking (two days) with no seeds to collect and Bleddyn complained to Sue (his wife) that there were no seeds to collect. We were only two days out, Sue said to Bleddyn. I said to Dan, We were still in the tropics. But they knew that. The day was hot. Sue had held her umbrella over her head, protecting herself from all that heat, and I wished again and again that I had brought one with me.

The forest of gingers was actually a swath of cultivated farmland. People were farming spices, for local consumption, and when I found this out, their guarded and circumspect relationship to me did not seem so inexplicable. While walking through this forest of the gingers I saw Dicentra scandens, Agapetes serpens, an epiphytic rhododendron, Begonia, Strobilanthes (blue and white), a yellow impatiens that Bleddyn said was not gardenworthy, Philodendron, Monstera deliciosa, Hydrangea aspera (subsp. Robusta, Bleddyn said to me), Tricyertis maculata, Arisaema tortuosum, Amorphophallus bulbifera, Osbeckia. Except for Dicentra scandens (the yellow-flowered climbing bleeding heart) and Begonia—though not this particular one—none of the plants were familiar to me.

At half past three in the afternoon we reached the village of Chichila. We had started the morning in Mani Bhanjyang at about four thousand feet and had walked up two thousand feet to Chichila. It was still hot but the clouds were coming in from Makalu, or so I was told, because if the clouds had not been coming, I would have been able to see the great Makalu, a mountain that I had never even heard of until I was nearing Chichila and every passerby greeted me with the word “Nemaste” and then “Makalu.” But we were not going to Makalu. We were going to look for flowers, or rather the seeds of flowers. Walking around the the village I saw little gardens in which were cultivated squash, corn, marigolds, and dahlias. We sat on a public bench in the hot sun and drank some beer we had bought. There was no other way for that beer to be had other than someone carrying it from Khandbari on his back. I had not seen, so far, animals put to this use. We had just started to enjoy how nice it was to sit with a beer in the hot sun after a day of walking up when, suddenly, without warning, it turned cold and windy and rain started to fall. It was as if, suddenly, we were in another day altogether, another day in another season. We moved into the shop where we had bought the beer and sat near a fire that seemed to have been burning all along, as if the people there knew that no matter how hot it got outside, eventually a fire would always be needed inside.

Two things happened as I was sitting inside by the fire drinking my beer: A beautiful woman, with naturally glossed, long black hair, saw my own braided-into-cornrow hair and she found it so appealing that she came and sat beside me to touch my hair. She picked up my long plaits and turned them over and over, and using gestures, she asked if I could make her own hair look like mine. I did not know how to tell her that my hairdo, which she liked so much, was made possible by weaving into my own hair the real hair of a woman from a part of the world that was quite like her own. And then when the rain came, Dan had gone to make sure that all our things were protected from getting wet. When he returned, I noticed a big, dull maroon-colored spot on his calf. I thought it was a peculiar bruise, but it was a leech enjoying life on Dan’s leg. We all shuddered, Nepalese and visitors alike, with varying intensity, at the sight of it.

The rain continued through dinner. Our dining tent leaked. We sat at our table, set with knife, fork, spoon, and paper napkin, and kept shifting around to avoid the water coming through our tent, eating by candlelight when from outside came the sounds of digging; it was our Sherpas making trenches that would guide the water away from our sleeping tents. It was so kind, so considerate. I had not thought of the possibility of drowning in my sleeping bag while traveling in the Himalaya.

That next morning (it was the eighth of October, a Tuesday, but it had no meaning for me, no usual meaning, it was another day), we were woken up with a cup of tea. After washing, eating breakfast, and packing up, we were off at seven-thirty. It was eighty-nine degrees Fahrenheit as we started out and the sky overhead was that magical blue innocent of clouds, and clear, though over in the distance, a thick milk-white substance—clouds—continued to hide Makalu from my sight. A mile or so on, I would round a bend, and unless I came this way again, I would have missed my chance to see a natural wonder of the world, a wonder I had not known of before. It was then I had a new feeling, a feeling I had never had before. It was something like fear, but I was not actually afraid; it was something like alienation, but I didn’t feel apart from the immediate world around me or apart from my friends, Dan and Sue and Bleddyn. I had been away from my home less than a week, I had two children, I could see their faces in my mind’s eye, I had come on this journey all because of the love of my garden. The garden, indeed, for here was Dan furiously trying to photograph a bundle of fodder a man was carrying on his back. The fodder turned out to be Viburnum cylindricum, a plant he treasures in his garden in Kingston, Washington. It is a beautiful Viburnum, with lance-shaped leaves that are deeply veined and white flowers loosely clustered together. It would be too tender for me to grow in Vermont but right for his climate. Dan followed the man for a little while, clicking away with his camera, recording this fact: a garden treasure for him is animal fodder in its native land.

Our porters had been late with our luggage the day before and so when we got to our campsite in Chichila we couldn’t change out of hiking clothes right away, and that had caused some irritation and the beginning of our little complaints. That next morning Dan suggested that we pack a change of clothes in our day pack and so not be dependent on the porters for dry clothes when we got into camp. He had remembered from his last trip here that they had a rhythm of their own: it all started out well, but eventually there would be some problem and porters had to be let go and new ones hired in the next village. Now as we walked on toward Num, the town where we would spend the night, a small worry cropped up: our porters seemed not to be as well-disciplined as the other porters with the other groups. They lagged behind and sometimes would disappear completely. We were in open land. The sky could not be more blue. The sun was a hot I had never experienced; it seemed to penetrate into my skin, going in one way and coming out the other. We marched on, sometimes passing the porters, but then they would rush past us carrying our bags, our tents, our chairs and tables, our food, our everything at an incredible speed. When we passed the porters, our hearts sank; when they passed us and rushed on ahead, we thought of the day’s end and our nice tents with sleeping bags waiting for us. We came to a little village that appeared to be the Himalayan equivalent of a truck stop. There was a shop, dark inside, and men were coming in and out. There was a lot of shouting and even drunkenness. It interested me greatly to know what was going on. Sunam would not let us linger to see anything or buy anything, but he had not so much control over the porters. We then descended into a forest the floor of which was littered with a chestnutlike fruit, but Dan and Bleddyn couldn’t quite agree on what this was, and I could see it was because it had no interest for them. I saw a climbing fern and then I saw my first maple, Acer campbellii. It wasn’t like the maples I am used to seeing, big-trunked, tall, and with leaves like a geometric illustration. It was slender and modest, and the leaves were only notched near the top, almost imperceptibly so. In the forest, the temperature fell to seventy-eight degrees Fahrenheit, and the cool was welcome. All around us we could hear the gurgle of water coming from somewhere and the ground on which we walked was soft with moisture. Dan was looking for another maple, not the campbellii, and he could not find it. He remembered from before that he had found it around where we were but now there was neither the tree nor seeds of it. However, he and Bleddyn found Paris and Roscoea, Tricyrtis, Thalictrum, and Lithocarpus, and something they said was fagaceous, but I had no idea what that could mean. Just outside Chichila they had found some Rosa brunonii in fruit, though they were not so very excited about that. We emerged from the forest back into the open sun, and I have to say that I began to flag then. At one o’clock we stopped for lunch in the village Muri. What made Muri a village, other than it said so on the map, I will never know. We ate lunch outside the one-room schoolhouse, a lunch that Cook had made inside the school. We had been walking for five and a half hours. It was eighty-nine degrees Fahrenheit. Many times during our walk we thought we would stop for lunch but we could never find a place that had enough flat space for Cook to make our meals, and water with which to cook our food, and then space for us all to spread out and eat. We ate our lunch, fresh vegetables and tinned fish, and some people—inhabitants from Muri or not, we could not know—watched us do so. Some of the children had hair that had lost its natural pigmentation; it had been black but had become blond, a sign that some essential nutrient was missing from their daily diet.

From our lunch spot, we could see Num in the distance. It was not far away at all. A couple of hours’ walk and that was mostly downhill. We started out, in the usually gingerly fashion, and then soon were confidently marching along. We walked on paths, sometimes along places that could only accommodate one person passing at a time, so someone would step aside, squeezing themselves into the brush or into a substantial rock.

On the way to Num, we passed by a nicely built house, it looked like a domicile I was used to; it had a house, a barn, and some other outbuildings. This scene of house, barn, outbuildings, did not look prosperous; it looked more like toil and eking out an existence. It looked industrious. I stopped for a rest outside a building that looked like a place where the cows would be kept, and I enjoyed this scene of familiar domesticity. Not long after, while walking all by myself, Dan and Bleddyn in front of me, Sue behind me, I heard Sue let out a muted, sympathetic scream. From behind me, she could see that my back was covered with blood, my nice blue high-tech synthetic T-shirt was covered with my red bodily fluid. A careful search was made of my clothes and my body but the leech was not found, and this left me with the feeling similar to one I had experienced when I was young and living in New York City and was always afraid of drug addicts breaking into my apartment and stealing my things so that they could then go and buy the drugs they craved. My fear of leeches became way out of proportion to the danger they actually posed. Every step I took was more dangerous than the leech burying itself in my upper back. Dan took a picture of my bloodied back and later when I took off the shirt, I was shocked at how much blood had stained its surface.

We got to Num, camped in the center of town, and sought out some beer. There was none at first, but then someone had some. The lack of readily available alcohol would come to be evidence of the presence of Maoists, but we did not know that then. The beer was warm. Num never, ever had ice. Num had no electricity. The beer was delicious. We found a seamstress and that was a good thing, for in the three days since we left Kathmandu we had shrunk. In fact, if there had not been a seamstress our clothes would be just fine. But I now see that we were aware that this would be our last chance to participate in life, that part of life in which you needed things done for you, luxurious things; your clothes needed tending, and your clothes were beyond necessary. We employed the seamstress to take in our underwear, fasten buttons, tighten pants, mend something or other. She did it well and we were very pleased.

That night there was a thunderstorm unlike any I had ever heard or lived through before. Dan and I were in our tent, tightly snuggled into our sleeping bags. It started to rain and the rain felt like water missiles directed at our tent. I was sure at any moment Dan and I would be drenched with water and part of our sleep routine would be sleeping in rain. But the tent remained upright. It was the thunder that was really frightening and remains so even in memory. The sound of the thunder was above and below us, far away and near at once, but whatever direction it came from, however near or far, it was not like any thunder I had ever experienced in real life or the imagination. There was that clapping and that roaring sound that I associate with thunder, but in this case it seemed to come from deep within the earth and the mountains that surrounded Num, and suggested that there was a more profound earth with mountains that was beyond Num. The warlike attack of rain and thunder continued throughout the night and I slept through it, and I was anxiously awake during it and then I slept through it again. We woke up to the continuing rain and then saw that we were completely locked into a thick mass of clouds. We could not see anything beyond twenty feet. We began to plan the day ahead, sitting around in Num, waiting for the weather to change days later, for the rain and the clouds that shut us in looked as if they would be that way forever. Books to be read were set out, journals to be updated, little bits of gossip to be retrieved from the depths of our brains. At about ten o’clock, the rain stopped falling, the clouds began to lift, dissolving into tiny wisps, and then the sun came out and shone with a brightness that seemed as if it had been just newly made. The whole transformation was in five minutes, from frightening and wet gloom, to hot sun and bright dry. Camp was immediately closed up and we were on our way again. We said goodbye to the campers we had met at the beginning in Tumlingtar, the ones from Spain and Germany and France. They were going off to Base Camp Makalu and would get there in seven days. They went right, we went left, and I had no thought of ever seeing them again.