THE MAOISTS

We left the village of Num at half past ten, the day showing almost no sign of the storm or whatever it was that had gone on during the night. We exited the village by going through someone’s backyard. They waved at us, calling out the usual Nepalese greeting, “Nemaste,” the equivalent of “Good day,” Sunam had told me. It was a simple enough greeting, but I couldn’t pronounce it properly. I never succeeded in getting myself to say it just the way I had heard it. We started going down, and this as usual meant that sometime before the day was over we would be going up. After three days, I knew with fixed certainty that to go up would lead to going down and vice versa. Up was always so hard and I never greeted it with any pleasure. Down became so hard that at the end of our journey, it took me four weeks for my knees to recover. Still, if we were to find anything worth growing in our gardens (this especially applied to me, since I lived in the coldest garden zone) we would have to go up.

I believe I was so glad to be on the path again, walking and not sitting or lying while a terrific storm, a storm, the fierceness of which I was not familiar, raged around me. In any case the going down seemed like not much to me. We had been mostly going up the day before and had gotten up to six thousand feet. Going up had been very hard, so hard that I began to think it a definition of real mountain climbing. It is not. The thing that I had not yet gotten used to was this: behind every rising was another one, higher and then higher it went. The ease with which I was used to going anywhere and everywhere had sunk deep into me. If I wanted to be someplace, I only had to find a way of transporting myself there. The idea that I had to actually get myself from one point to the other, through my own effort, was hard to take in then and hard to take in even now, months later, as I write this. But what had I imagined when I set out to do this? I had thought I would walk of course, I just did not understand the kind of walking that was required of me. And so it was that day, our fourth day out, I felt that my legs were adjusting to this walk, this path, that cut through huge slippery rocks and fallen tree trunks. I walked carefully, I had to, a couple of times; and I fell flat on my bottom because I had made a misjudgment in my steps.

And then suddenly again, there was that dramatic, magical change that I was fast getting used to. We had started out, just after the rain, and it was still chilly, so much so, that we bundled up in sweaters. Suddenly it was hot. We had gone from a moist, cold, dark forest into open woodland. Suddenly it was so hot that Dan wished for a secluded spot, where there was a stream that flowed into a pool so that he could take a bath. He did not find the two together. As we walked along in that whole forest, far away from everything in the world, secluded spot and stream that flowed into a pool never did meet up. Perhaps to make up for not finding such a thing, we walked into a world of butterflies. At first, there were only bright yellow ones, dancing in the blue clear air just above our heads and in front of our faces, and there were many of them, as if someone or something nearby did nothing but produce such wonders. But then many other different-colored ones came by. And they came in combinations of colors that are always so startling when you find them in nature, and only in nature are such combinations of colors, maroon and green, red and gold, red with black, blue and gray, aqua blue and black, that never seem garish. I had a camera with me but I had no interest in photographing them. I couldn’t anyway, they were never still. This was such a pleasant antidote to the leech of the day before. I never did run into such a sight again, a swarm of so many different butterflies, but the leech was a constant worry.

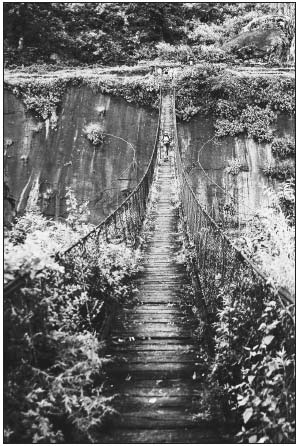

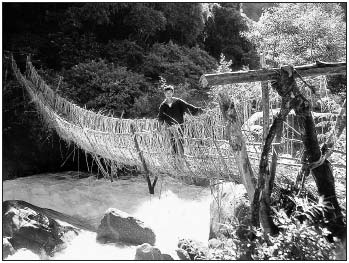

Author crossing one of the precarious bridges spanning the Arun River

Eventually, we could see the Arun River in the distance. We could also see the bridge over which we would cross it. That first bridge was a pleasant dream compared to some of the bridges I had to cross later, but the Arun at that point was wide and probably deep right there, and the bridge was narrow and long and I had never crossed such a bridge before. It was just before we crossed the bridge that I saw some Nepali script and a drawing of a star (as in red star) in bright red ink on the concrete foundation of the bridge. Maoists, I thought, at last here they are, this is a sign of them. They had forever been on my mind; I had weighed their presence and activities in Nepal before I came. Before I came, Dan had told me they were not killing foreigners and instead of saying back to him they are killing people, so we mustn’t go, I was only too glad to be a foreigner and so become exempt from their wrath. Still they were killing people, and I have noticed that when someone starts killing people, though at first they draw a line at the kind of people they will kill, eventually that line gets erased as they start killing some other people. I can’t really take the word of people who will kill their countrymen but not me. I only believed Dan because I wanted to, in truth I didn’t believe Dan at all. I was afraid that if I ran into the Maoists they would kill me. Still, the thought of the garden and to see growing in it things that I had seen in their natural habitat, to see the surface of the earth stilled, far away from where I am from, perhaps I would be lucky and see only the writings of the Maoists, perhaps I would never, ever see them at all.

I crossed the Arun River on that bridge. It was exactly half past twelve and we were at an altitude of 2,044 feet. Everyone was very encouraging. They had all done it before. Sunam and Mingma and Thile did not laugh at me; the porters did not laugh at me. Sunam waited for me at the other end and told me how brave I had been to do it. He was very kind to me and was always helping me to put the best face on everything I did awkwardly. Early on he had shown me our route on the map, and I must have looked strange for he said, with much forced cheeriness, that it would be very beautiful, as if he knew to someone like me the word was a sedative. Once, when I had, after a great deal of huffing and puffing, got to the top of a ridge, only to see yet another ridge and then beyond that a huge mountain, I asked him the name of the mountain I saw ahead of me. He said, “That is not a mountain, that is a hill and it has no name.” Exactly what he said. But of course, there are no hills in Nepal, there are no meadows, there are no valleys, there are only things that might be called hills and meadows and valleys, all of them little interruptions, little distractions in a landscape that is all mountain. I knew there were no hills but when he said that, I became truly silent. Earlier I had asked him about the red markings on the bridge, I had wondered out loud to him (though I whispered it) if that was a sign of Maoists. He said, no, it was just the Nepalese people expressing their opinions in the recent election. Of course, some of those opinions in the recent elections were those of the Maoists. I knew that but I did not say this to him. And another reason I had to take everything he said with a large grain of salt: Whenever people we met seemed to be talking about us, though me in particular (sometimes it was the color of my skin, sometimes it was my hairstyle), if we asked Sunam what they were saying, he would say he didn’t understand their language. He would say that they were speaking in a local language that he didn’t understand. The mystery of what Sunam did and did not understand became a source of much amusement. What are they saying? we would ask. I don’t understand, Sunam would reply. A joke between Dan and me was: “What are they saying?—[a short pause]—I don’t understand,” and this would make us laugh until we ached in the last places left in our bodies that were not in pain from our exertions.

At half past one and at an altitude of 3,030 feet and temperature ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit, we stopped and had lunch in a place that was not even on the map. It was on the tiny plateau of a steep climb we had just made. It took us an hour to get there from the crossing of the Arun River and it was less than half a mile. Of course Cook and his assistants were there already when we arrived and they had our hot beverage waiting for us. We had a lunch of potato salad, mushrooms, and boiled melon. A young woman sat on the porch of her house, lovingly combing her own very beautiful, long black hair, trying to make it free of lice. From her exquisite strokes, I could see that she had much practice, which meant that it would never be so. She looked very sad and lost in that way people do when they are doing a good thing but only for their own benefit.

We walked through a neatly arranged village with houses made of wood and painted white but it was too early to stop and, in any case, the village seemed to take up all the flat spaces where we could camp. It was hot, tropical, and I recognized plants from Mexico: bougainvillea, Dahlia, marigold, and poinsettia especially. Every house was surrounded by a food garden, and though I know that is unusual, a food garden, the way they grew food, squash vines, for instance, carefully trellised and then allowed to run onto the roof of a nearby building, was so beautiful, it became a garden. And in making this observation, I was reminded again that the Garden of Eden is our ideal and even our idyll, the place where food and flowers are one. After that, food is agriculture and flowers are horticulture all by themselves. We try to make food beautiful and we try to make flowers useful, but it seems to me that this can never be completely so. In this village almost every building had something written on it in red paint and the drawing of the sun in much the same way I had seen on the bridge earlier. I did not ask Sunam where we were, for I suspected it fell into the category of a place with no name, a place where he did not understand the language. We walked on and spent the night on the school grounds of the next village, a village called Hedangna. That village had a center concentrated around a little fountain of water, built not for beauty but for necessity. From the school yard where we camped, we were surrounded by the most stunning view of a massive side of a cliff from which poured white, stiff bands of water. They were waterfalls, but they didn’t seem to fall in the way I was used to. It looked as if they had been set down there on purpose, so constant was the flow. It was so stunningly beautiful in its cruelty. For the people who looked at it, myself included at that moment, could die from want of it. It is very hard to get water for use in this place where there was so much of it. Water could be seen everywhere, but difficult to harness for human uses. After a few days, we looked more like the people who lived in this place than as if we did not. We looked as if we longed to bathe and I smelled that way too. As if to remind us of how the day had begun, just before the sun vanished, not set, vanished, a rainbow suddenly arced out of the clouds that were keeping the tops of the mountains ahead of us in a shroud. For all of that, we calculated that we had walked three miles that day, we were only three miles away from Num, and yet it was another world altogether. As if I was looking, in a manner of speaking, at a set of pictures, of the same event but from different angles and seen at different times of the day. Num was only three miles away. I could even see it across the deep valley from which I had come, but the distance seemed imagined even though I could actually see it.

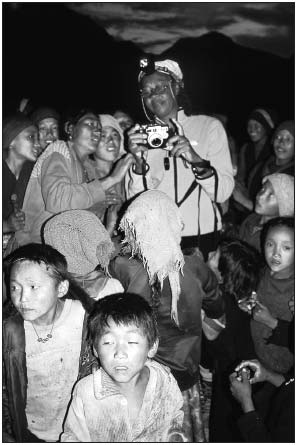

That night, we were surrounded by more children and adults than usual, and Sunam told me not use my satellite telephone. That was how I knew he was worried the Maoists were around. They came to see us, boys and girls in equal number, so it seemed to me; a man carrying a baby, but he could not have been its father, he seemed so young. An old woman came over to me and literally examined me. She picked up my arm and peered into my eyes and touched and poked my skin; then felt my braids and loudly counted them out in her language, a language which Sunam, I am grateful to say now, told me he did not understand. We went to sleep in our tents, Sue and Bleddyn in theirs, Dan and I in ours. Dan read some of a book he said was very bad; I tried to read my Smythe but found I could not concentrate on his adventure, for I was having my own.

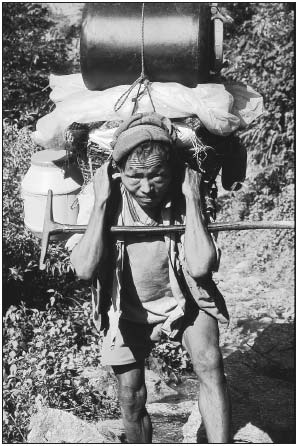

That next morning we left our camp at half past seven. It was eighty-three degrees Fahrenheit. We had eaten a breakfast of rice porridge and omelet with onions. How good everything tasted. How good everything looked. The world in which I was living, that is, the world of serious mountains, the highest peaks in the world, over the horizon, if only I would just walk to them, the world of the most beautiful flowers to be grown in my garden, if only I would just walk to where they were growing. I was trying to do so. That morning, I could see that on the top of one of Sunam’s “hills with no name” there was snow. The day before, Bleddyn had said to me that I should try to find Actaea acuminata because someone named Jamie would give me Brownie points. Dan said we were too low for finding this; Bleddyn said, yes, but soon we would be. I, of course, would have no idea what this plant is even if it were my nose itself. Still, I thought I would look; and much to Dan’s and Bleddyn’s annoyance, would always say, “What is this?” in my most studentlike voice possible. They were not pleased and I noted they were always way ahead, way out of earshot of me. They found an Amorphophallus at an altitude of 4,490 feet and it had seed, which they collected. And that was exciting, though mostly to me, for I had never found an Amorphophallus before. I had never even thought of this plant before. It looked like a jack-in-the-pulpit except that the spathe stood upright. Bleddyn thought there was sure to be some Daphne bholua growing right around where we were. But we could not find any. Then we came upon a village, again not one found on the map, and there in the yard of one of the houses were sheets of paper hung up on a clothesline, presumably to dry them. Dan and Bleddyn were very excited by this, for Daphne bholua is the plant often used for making paper. They ran to the man’s house to buy some of the sheets of paper and he must have been very surprised by the sudden increase in his business, but he didn’t show, at least not so that I could tell. Dan bought twenty-five sheets, I bought twelve sheets, Bleddyn bought quite a lot because he needed the paper to dry the leaves of specimens he was collecting. After our little shopping spree (and it did feel wonderful to buy something), the burden of which we simply passed on to our porters, there ensued a small disagreement between Dan and Bleddyn over whether the paper was made of Daphne bholua or Edgeworthia gardneri. This paper, by the way, was not some exotic thing being made for the use of people far away. It was being made for everyday use by the people in the surrounding area. It made me think of a beautiful young woman I had met the day before in the village of Hedangna. She was returning home to her village with a bag of salt on her back. She had gone to Hile, a big town that has bus service to Kathmandu, and purchased a load of salt. It was six days’ walk from her village of Ritak, a village way up near the Tibetan border, to Hile and six days back. She carried with her a little pot and some rice and a thin foam-rubber mat. Often we would pass people going in one direction or the other (though, when they were going in our direction, they passed us easily) who carried on their backs a pot and grain of some kind and their foam mattress; sometimes we passed them cooking their food, sometimes we passed people asleep in the path, as if they couldn’t go one step further and just lay down where sleep overcame them.

The author’s digital camera offers villagers a rare glimpse of their own images.

We were walking now in wide, open, rocky meadows. For a while we walked along a dangerous ledge and there were lots of sighs, on my part. I saw a beautiful yellow Hibiscus in bloom; it looked somewhat like Abelmoschus manihot, but if it was that, it was the most beautiful form of it I have ever seen. It was a bright, glistening yellow and the blooms were huge. I never found any seed on it. Then we were in deep, moist shade, not exactly a forest, but a shady enough place for there to be found Codonopsis. We could smell it though it could not be found immediately. Eventually Bleddyn found a plant with some seed. It was ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit when we stopped to eat our delicious lunch of tinned baked beans, luncheon meat, and spinach. We stopped near a stream that was rushing downhill to meet the Arun, and we sat in it in a place where it made a pool, with all our clothes on.

That afternoon we crossed the Arun River four times, and three of the four bridges were quite sound ones. The one that wasn’t I dealt with quietly. That afternoon also we saw some white-haired monkeys way above us in trees, and they made the most wonderful sounds to each other. I was so happy to see them; and this suspicious thought crossed my mind, that I was happy to see them because to see them is to claim them. Claiming, after all, was the overriding aim of my journey. Dan showed me a vine with grapelike leaves and stems covered with golden hairs. It was Clematis buchananiana, something new to me. That particular plant had no seed, and though we came across it many times, we never found any with seed and this even I regret.

By the time we made our final crossing of the Arun for the day, we were tired. We wanted to stop and make camp but Sunam said not then. We passed through rice paddies, and untended boggy places. We saw much marijuana growing wild, we saw people smoking the marijuana. Finally, at half past four, seventy-nine degrees Fahrenheit, 3,570 feet altitude, we came to the village of Uwa, the place where we would spend the night and a village under complete Maoist control.

The minute we walked into the village we could see them. There were banners hanging from house to house, and on the banners were portraits of a red sun and, I assume, the same sayings we had seen on the bridge. Sunam had actually reached the village an hour before we did. He usually went ahead of us to make sure our things were all set up for our arrival. But when we got to Uwa, one hour later, the porters were standing around with their burdens at their feet and Sunam was nowhere to be seen. He was actually in negotiations with the head Maoist. The head Maoist either couldn’t or wouldn’t give us permission to spend the night. There were many consultations. Finally we had to give them four thousand rupees, and at almost six o’clock we were allowed to go and make camp on the school grounds. To get to the school grounds we had to thread carefully through a rice paddy, carefully because we didn’t want to ruin the crop and because we didn’t want to get our shoes wet. That was done well enough, and we were just about to sink into the deliciousness of the danger we were in, when we realized our shoes were crawling with leeches that were eagerly burrowing into our thick hiking socks, trying to get some of our very expensive first-world blood. I shrieked of course, then took off my shoes and socks, then searched all the parts of my body that I could and asked Sue to search the parts of my body that I could not. She did and I did the same for her.

Things began to look grim. Sunam thought it would be best if he kept my satellite phone. The Maoist had told him that we would not be allowed to pass on through the village. The four thousand rupees were only for spending the night. We began to think of alternate routes. Sunam really began to think of alternate routes. Around that time, Sue and Bleddyn became Welsh and Dan and I became Canadians. Until then, I would never have dreamt of calling myself anything other than American. But the Maoists had told Sunam that President Powell had just been to Kathmandu and denounced them as terrorists, and that had made them very angry with President Powell. I had my own reasons to be angry with President Powell too. In any case I had noticed that all of the bridges I walked on to cross from one side of the Arun to the other had a little notice bolted onto the entrance, thanking a donor for the bridge. The countries mentioned were either Canada or Sweden. I had no idea how familiar Maoists were with people from Canada and Sweden. Canada seemed so broad, non-particular, open-minded. I decided, that if asked, I would say I was Canadian. I didn’t feel ashamed at all.

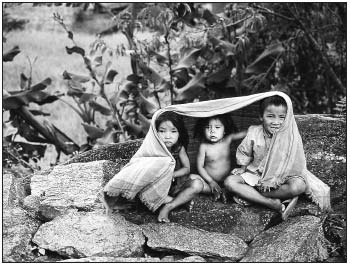

Village children

Whenever we had stopped to spend the night in a village, no sooner had we arrived then it seemed all the children in the neighborhood had come to stare at us. A few adults would come too, but mostly it would be children and they would stare at us as we cleaned ourselves, ate, went to bathroom (a little tent that we carried with us and was almost always the first tent to be set up wherever we were), even just sitting around reading. In this village no one came to look at us. All the children seemed to have walked up to a ledge that was right above us, and they climbed into the trees and began to make the sounds that some monkeys, who were also above us and in the trees, were making. It was meant to disturb us but it didn’t at all. Nothing could be more disturbing than sleeping in a village under the control of people who may or may not let you live.

The village was situated in a rather strange place and there must be a good reason why people settled in just that spot. It was surrounded on all four sides by high steep cliffs. It was more like a dam, a place made for storing things, than a place to live. It had three openings through which people could come and go. But the cliffs were so high that they shrank even the vast Himalayan sky when seen from the village. That night we did the usual leech check. There was no laughter from our tents. We got up the next morning with the usual tea brought to us by Cook’s assistant and an unusual amount of anxiety. Would they let us proceed or send us back? They let us go. Sunam gave them some more rupees, how much more, he wouldn’t say. He made them give him a receipt to show to the other Maoists, if we should meet them, that he had already paid what could be made to seem like a toll, but Dan said with surprising anger, that it was extortion. Sunam had learned from someone that we should avoid spending the night or even going near the village we had planned on spending the night in because the people who controlled that village were even more committed to Maoism and took even stronger objection to the words President Powell had spoken in Kathmandu.

We headed out of Uwa at half past seven, so very glad to be leaving. No one spoke to us, not even to say the usual Nemaste! What a great hurry we were in. And we started up again, going up away from the Arun. It was good to be up but by going up high so early in the day, it meant something bad for Bleddyn. He had wanted to take a short hike up the Barun River and collect some seeds. How disappointed he was to see it, a thin streak of milky white coming down the mountain and ending in the Arun, which was way below us. He cursed the Maoists. We had been walking for six days now and there had been nothing substantial to collect. Nothing for me anyway. I would have done this, even if I had not been interested in the garden. Just to see the earth crumpling itself upward, just to experience the physical world as an unending series of verticals going up and then going down—with everything horizontal, or even diagonal, being only a way of making this essentially vertical world a little simpler—made me quiet. I saw the people and I took them in, but I made no notes on them, no description of their physical being since I could see that they could not do the same to me. I can and will say that I saw people who looked as if they came from the south (that would be India) and people who looked as if they came from the north (that would be Tibet). I saw some people who were Hindus (they were the same people who looked as if they came from the south), and I saw some people who were Buddhists (they were the same people who looked as if they came from the north).

As usual, we were walking along a ledge and a false step in the wrong direction could land any one of the four of us a few hundred feet down, either in the crown of trees or on sheer rock, for sometimes below us was thick forest, or sheer cliffs at other times. We stopped for lunch after one o’clock. The Arun was in full view and so was the Barun running into it. Even from so far above we could hear the roar of their waters. We stopped for lunch and it was memorable to me because that was the last time we had bread. For dessert, we had toast with marmalade and tea. It was the best toast and marmalade I had ever had, and when eating it I thought, This is all I’ll eat for the rest of the time I am here. But when I requested it that night for dinner, I was told that the last of the bread had been eaten at lunch. It dawned on me then that requests were out, and I stopped asking for anything with the expectation that I would receive what I asked for. On again we marched after lunch, feeling a lot better because we could see our village in the distance and also because the collecting was becoming exciting, at least for any gardener who lives in at least two zones warmer than the one in which I make my garden. We were at an altitude of a little under six thousand feet and among the things Dan and Bleddyn collected were some Hydrangea aspera subsp. strigosa, Boehmeria rugulosa, Costus sp., Acer (maple), Paris polyphylla, Woodwardia sp., Anemone vitifolia, Rubus lineatus.

It was about three o’clock when we arrived in the village, feeling pleased with ourselves for having avoided the Maoists, but something made Sunam change our camping spot. We had met a man who had just lost the tips of three of his fingers on the left hand. Someone must have told him we were coming for he was waiting for us with his hand outstretched, and he was crying. Dan, who always carries a little first-aid kit in his backpack, cleaned the wound and then put some Mercurochrome and a Band-Aid on the man’s fingers. We had a little debate over whether to give him any of our Tylenol to relieve him of pain right away since we could not part with enough that might give him some comfort for many days. This ended with Sunam telling us that the village would not be where we would spend the night. We would have to march on a little further up above the village. Whatever he learned about our presence in the village, he never told us. We just were told that we would be camping a little higher up. We then took a road out of the village, going around it, not through it, and seeing some beautiful houses made of clay, painted white with some kind of stencil decoration around the windows and doors. I had seen something similar two nights ago when we stayed in the village of Hedangna, but there the stencil was done in the color brown while here it was done in blue. Bleddyn came across a pink Convolvulus, whose fragrance we could smell long before we saw it. But the Convolvulus had no seeds and, after the botonists lamented that fact, we just walked on and hoped to find it somewhere else with seed. We saw it twice again but always it was in flower, never having any seed.

Our way now, having left the village, was a steep walk up a landscape that had not so long ago collapsed. We had to climb up and then cross over a recently ravaged hillside (in any other place, it would be a mountainside), that had perhaps not too long ago been the result of a landslide. The evidence of landslides was everywhere, as if proving what goes up must come down is necessary. We, and by this I mean Sue, Bleddyn, Dan, and me, expressed irritation at this with varying intensity (Dan and Bleddyn minor, Sue almost minor, me loudly) and then marched on. Two men, dragging long thick trunks of bamboo attached to porters’ straps wrapped around their foreheads, passed us as they were going the other way. They seemed to take our presence for granted, as if they knew about us before they saw us, or as if our presence was typical, or as if we did not matter at all. We marched on; by this juncture we were marching—the leisureliness of walking was not possible once we came in contact with the Maoists. When we got to the top, as usual, it was not at the place of destination. What had seemed to us as the top of the mountain was only the place where the avalanche began. The mountain continued up and it was as if the face of the mountain had decided to fall down starting in its middle. We had to go up some more because, for one thing, Cook, who was always ahead of us—he could walk so fast—could not find any water coming out of the mountain. And also we needed to find some level ground on which to cast our tents, forming our little community of the needy, dependent, plant collectors and the Nepalese people, whose support we could not do without. We kept going up, each turn up above seeming to hold the desirable flatness and water too, for how could that not be so when everywhere we looked we could see a milky white and stiffly vertical flowing line of a waterfall. But Cook went flying up and then went flying down to Sunam, and there were consultations. On our way up, past the place where the avalanche began, we met a herdsman, though before that we had met his cows. At first we made way for the cows because we thought we were in the cows’ home and perhaps we should be respectful of them. But the cows remained so cowlike, stubborn and potentially dangerous, if you only considered their horns, and in this case they seemed to really consider their horns. The herdsman managed them beautifully, guiding them down and away from us, taking them into the steep bush-covered slopes away from the path they were used to traveling, just to keep us calm. I would not have thought about this incident of the herdsman and his cows again but I saw him the night after this and three nights after this again far away, for me, from all these difficulties.

Porters’ loads can exceed one hundred pounds.

Between the cows and their herdsman and Cook not finding water to cook us supper, we grew irritable. From our place way up above the village, and even from that way up above the place where we had eaten our lunch, we were closed in. The sun was setting somewhere; we could see the light growing dimmer, literally like someone turning the wick of a lamp lower. We, and by that I mean me in particular and especially, began to whimper and even complain. For one thing, from our vantage point, so high above, we could see the porters carrying our baggage and the tents and all our other supplies and necessities, resting at the place where we had eaten our lunch. So if Cook should find a place in which to cast camp, and casting camp always depended on him, we—and we were so important we felt then—could not enjoy camp, for the things that made sitting in camp comfortable were half a day’s walk away. What had the porters been doing all day? someone said—meaning, What had they been doing when we were exploring the landscape, looking for things that would grow in our garden, things that would give us pleasure, not only in their growing, but also with the satisfaction with which we could see them growing and remember seeing them alive in their place of origin, a mountainside, a small village, a not easily accessible place in the large (still) world? We were then having many emotions, feelings about everything: The Maoists were right, I felt in particular: life itself was perfectly fair, people had created many injustices; it was the created injustices that led to me being here, dependent on Sherpas, for without this original injustice, I would not be in Nepal and the Sherpas would be doing something not related to me. And then again, the Maoists were wrong, the porters should be fired; they were not being good porters. They should bend to our demands, among which was to make us comfortable when we wanted to be comfortable. We were very used to being comfortable, and in our native societies (Britain, for Bleddyn and Sue; America, for Dan and me) when we were not comfortable, we did our best to rid ourselves of the people who were not making us comfortable. We wished Sunam would fire the porters. But he couldn’t even if he wanted to. There were no other porters around.

We were hungry and tired. It really was getting dark. The sun was going away, not setting. We couldn’t see it do that, we could only see the light of day growing dimmer. Still, we could see the porters. They were far away. Way below us. The most forward of them were not even near the place where we had come across the fragrant Convolvulus. And there was no real place to camp. No doubt I will always remember this evening, for it was the evening where we could not decide where we would stay, among other things. At just about the time some of the porters were traversing the unpleasant landslide, Sunam decided that we would cast our camp at a spot that was the only level site in the area. Cook had found a stream nearby, in any case, and that was always the deciding factor. We were three-quarters of the way up a steep rising of rock covered with some Taxus and Sorbus and, instantly recognizable to me, barberry and some kind of raspberry (Rubus). We made our way through them and found we were in a field that had growing in it mostly wormwood, some kind of Artemisia. What a relief. And then someone pointed out a leech and then another and then another, and we soon realized that we would camp, we would spend the night in a field full of leeches.

Immediately as we entered this area we were attacked by them. At first it was just one or two seen on the ground, then leaping onto our legs. Then we realized they were everywhere, like mosquitoes or flies or any insect that was a bother, but most insects that were a bother were familiar to us. The leech was not something with which we were familiar. And why was it so frightening, so strange? It was just a simple invertebrate, after all. But a leech is a different kind of invertebrate. To see it whirl itself around as it gathers momentum to fling itself dervishlike onto its victim is terrifying; to see the way it burrows into clothing as it tries to get next to a person’s warm skin so it can first make a gash that cannot be felt, for it administers an anesthetic as it bites, is terrifying; to see a thin, steady stream of blood running down your arm or your companion’s arm is terrifying, for the leech also administers in its bite an anticoagulant. Was it because it was silent, making no noise of any kind that made it so reprehensible, so shudder-making? A leech, just the mere words would make us jumpy, cross. When Dan had first told me of this journey, he had mentioned leeches as one of the disturbing things to be encountered. He had also mentioned altitude sickness and deprivations of everyday comforts such as showers, bathrooms, people you loved, but I remembered leeches more than I remembered Maoists, even when I got to Kathmandu and saw the evidence of a civil war, soldiers with submachine guns everywhere. I remember Dan saying that there will be leeches but we will have so much fun. That night above the Arun River, on the opposite side of the Barun River, looking into the Barun Valley, I was not concerned with anything but the leeches. And so when we walked into our campsite and I saw these little one-inch bugs whirling around and then leaping into the air and landing on us, my spine literally stiffened and curled. I could feel it do this, stiffen and then curl. I screamed loudly and silently at the same time. And then I did what everybody else was doing, Sherpa, porter, and fellow botanist, I forged ahead, grimaced, laughed, searched for the parasites, found them, and picked them off and killed them with great effort and satisfaction. Even so, the disdain and unhappiness for spending the night in a field of leeches never went away.

The stoves were lit and Cook began to make us food. There was no room for our dining tent so the table and chairs were set out on a tarpaulin. We had tea and biscuits, nothing could stop this—and how grateful we were for this. Night fell suddenly, as if someone, somewhere, decided to turn out the light because it suited them right then. After being hot all day, suddenly we were cold and wanted very much to put on our warm clothes. But the clothes were way down below. Sunam had gone back down to hurry up the porters who were carrying our suitcases. The laxness of the porters made Dan and Bleddyn annoyed not only because they couldn’t change into dry clothes but also because they wanted to review their collections of the day, try to do some cleaning of seeds, and make some entrances into the collection diaries. We were sitting on our chairs in the open air and looking out on the Barun Valley at night in the Himalaya. It was beautiful. But the leeches kept coming at us. Finally we set up a sort of Leech Patrol; each person, the four travelers, looking for leeches in four different directions.

Our luggage still had not arrived and there was much discussion regarding what the porters had been up to all day. And there was no chang, a fermented beverage made from millet, or any other kind of alcoholic beverage as far as we could tell, in the Maoist area. We—I, really—felt small, as if I were a toy, inside the bottom of a small bowl looking up at the rim and wondering what was beyond. The person who lived in a small village in Vermont was not lost to me, the person who existed before that was not lost to me. I was sitting six thousand feet or so up on a clearing we had made on the side of a foothill in the Himalaya. Only in the Himalaya would such a height be called a foothill. Everywhere else this height is a mountain. But from where we sat, we were at the bottom—for we could see other risings high above us, from every direction a higher horizon. The moon came up, full and bright. And it looked like another moon, a moon I was not familiar with. Its light was so pure somehow, as if it didn’t shine everywhere in the world; it seemed a moon that shone only here, above us. It sailed across the way, the skyway, that is, majestically, seemingly willful, on its own, not concerned with having a place in the rest of any natural scheme. It was a clear night. We sat on the tarpaulin, on the chairs around the table in a circle, huddled toward the middle to see more clearly and readily the leeches. We were looking up at the sky, clear and full of stars, the light from the moon outlining the tops of the higher hills, and they were hills when placed in context of the true risings beyond which we could not see.

It must have been near nine o’clock when we had our dinner. I should have been hungry but I wasn’t. I felt sick, my stomach hurt, I wanted to throw up. I was served but could not eat. Dan said that perhaps it was the altitude. We were up at about six thousand feet. Dan flossed and brushed his teeth. I did not. I don’t know what Sue and Bleddyn did. Dan and I went into our tent. He reminded me to check my shoes and socks for leeches, to check myself for leeches, to check the space around my sleeping bag for leeches. All was clear and then we settled in to have our nightly review of the day’s events, which mostly resulted in huge cackling and laughter. We had finished our cackling and laughter and were about to go to sleep when there occurred a huge storm of fierce thunder and big rain—the kind of thunder and rain that made me think it was pretending to be so fierce and then I thought it was the end of the world, we would never leave this place, the storm would so change the world that we would be forced to stay in the leech field in our tents forever And it reminded me that this was my first question when confronted with the landscape of the Himalaya: Is this real? It is real enough. We heard Bleddyn calling out to us, Dan and me, that we should check our tent window. Dan and I turned on our flashlights and saw an army of leeches trying to penetrate the window, a square made of mesh netting which served as ventilation on the side of our tent. It was horrifying, not only because we were so far away from everything that was familiar to us. All day as we had marched along, taking a new route to escape the Maoists and their demands, which we felt might include our very lives; we felt endangered, assaulted, scared. In reality it was just about a dozen leeches, but how to explain to a leech that we did not like President Powell? How to tell a Maoist that Powell wasn’t even the president? At some point I stopped making a distinction between the Maoists and the leeches, at some point they became indistinguishable to me, but this was only to me. Fortunately I had acquired some DEET, against Dan’s advice, that justifiably denounced insecticide, and I always carried it with me. I reached into my day pack, which was at the foot of my sleeping bag, and sprayed it furiously on the leeches trying to get into our tent and they just fell away and I hoped they were dead. I could not sleep. I wanted desperately to pee but when I thought of the leeches leaping up and then burrowing themselves in my pubic hair, I decided to hold it in. But then I couldn’t fall asleep and so I went out of our tent, just outside the entrance, and took a long piss. This was a violation of some kind: you cannot take a long piss just outside your tent; you are not to make your traveling companions aware of the actual workings of your body. Not to allow anyone an awareness of the workings of your body is easy to do in our normal lives, where we have access to our own bathrooms, thirty-minute showers of water at a temperature that pleases us, toilets that allow their contents to disappear so completely that to ask where to could be made to seem a case of mental illness. After I had my pee, I took another sleeping pill and went to sleep and did not dream about Maoists, leeches, or anything else. And then I was awakened by a terrifying sound of land falling down from a great height, an avalanche. It sounded quite close by. The morning didn’t come soon enough. We got dressed rapidly (I did not brush my teeth), packed up, ate, checked ourselves for leeches, and left. We never wanted to see that place again.

We got going without regret, without looking back, without even wishing for another moon like the one we had seen the night before. It was the most beautiful moon I had ever seen without a doubt, but I would not spend a night in a field full of leeches just to see another one like it. We marched upward the steep climb to the top. Many times the thick growth of maple, oak, Sorbus, and yew would thin out and clear up and I felt the top was near, but this clearing was only a pause leading up to more thick forests and darkness and moistness and slippery paths, almost falling down in a way that could be dangerous—and this was not a place to have an accident of any kind. To twist your ankle here wouldn’t be good at all; it would cause much misery and inconvenience. Then again, if your heart cracked out here, how much longed-for would a twisted ankle be? We climbed up to nine thousand feet, finally reaching a clearing that was somewhat level. We were at the very top of the ridge of the mountain we had just walked up. Almost as a reward, Dan immediately found a Cardiocrinum giganteum that was almost twice as big as the tallest of us, and that was Dan himself. It had lots and lots of seed. How happy he was and Bleddyn too. And after that we seemed to find nothing but Cardiocrinum giganteum, they were everywhere. I remained deeply in the experience of the night before: The Moon, The Leeches, The Landslides, The Escape from the Maoists, all of it capitalized. We walked down the forested hillside, plunging into a gulley, going more steeply down it seemed than we had gone up the day before; the sun hot overhead, the sky clear of clouds and blue as if it had never known otherwise. Down we went, toward the Arun again, passing through a thick forest of oak, Aralia, and Berberis. I kept my eyes peeled to the ground, carefully picking out each step I took, for we were on moist ground. In fact the earth seemed to be only a leaky surface; I could hear water trickling, I could feel my feet slipping on the sticky wet ground. From time to time I fell and cursed myself for doing so. But then we were out in the open sun and the ground was dry and we were walking in nothing but red-fruited Berberis. But I couldn’t collect any seeds because they are on the list of banned seeds, seeds not to be brought into my country. As usual, our destination seemed farther away the closer we got to it. We could see a village high above the other side of the Arun, and it was the village beyond that was our destination. We stopped for lunch just before crossing a river, that fed into the Arun, at a place called Sampung, and then one hour after lunch crossed the Arun and started climbing up again. That day after the night spent in the field with the leeches, we walked for nine hours and stopped in Chepuwa just a mile or two from our destination, the village of Chyamtang, because it was getting dark. We were so very tired and cross, though not with each other and not with the people who were taking care of us.

When we made camp in the schoolyard in Chepuwa, we were immediately surrounded by children, one of them wearing a T-shirt that had the word Paris written on it. His T-shirt referred to the city, not the plant. In fact, though the plant Paris was native to the very place he is from, he most likely had never paid attention to it and so had never seen it. In any case, for dinner we had reconstituted food, Chinese food at that. I was not hungry. I went to bed at eight that night and noted that we were at an altitude of seven thousand feet. We had begun the day at six thousand feet altitude, walked up to nine when reaching the top of the hillside on which we had spent the night, walked down to three thousand feet when we crossed the Arun, and now were spending the night at seven thousand feet altitude. If I was suffering from the dreaded altitude sickness, I did not know it. I only felt tired and lonely and my head did ache, but it ached in the way my head always aches. The next morning, on the thirteenth day of October, nine days after we left Kathmandu, each of them spent walking at least ten miles, we walked the two miles to Chyamtang and decided to spend a few days there.

In that long hike the day before from the field full of leeches to our campsite in Chepuwa, I had felt I was negotiating my very existence with each step. But while I spent nine hours all wrapped up in myself, wondering if this plant (Paris, for instance) which looked awfully familiar and so much so that it had to be something else, was really itself, wondering if I was seeing something new, and always wondering if I could grow it—and when I realized I could not, I had no interest in the thing before me whatsoever. While I had spent nine hours being a gardener, in other words, Dan and Bleddyn and Sue were gathering seeds. They had collected and recorded the seeds of thirty-nine different plants, among them: Anemone vitifolia, Rubus lineatus, Cautleya spicata, Paris polyphylla, Schefflera sp., Disporum cantoniense, Arisaema tortuosum, Tricyrtis maculata, Philadelphus tomentosus, Hydrangea anomala, Crawfordia speciosum, Viburnum grandiflorum, Aralia, and many ferns.

When we reached Chyamtang, we unpacked everything and aired out our clothes and sleeping things. It was a brilliant day of heat and bright light. Dan told me how lucky we were. Apparently, it could have been raining, it could have been cold. I was grateful for all that and grateful too for being able to spend the day lying down and reading and certainly not hiking. It was around then that Sue and I said to each other how hard the whole thing was. Sue came down with a cold. I came down with a case of loss of sense of self, but not only was this not new, I actually enjoy this state and were it not for that, I really would be in a state of loss of sense of self, only I would have no way of knowing so.

All the same, how welcome this day was. A Pause. Sue and I could hardly believe it. Of course, Dan and Bleddyn went off seed hunting or collecting and they expected Sue and me to clean the seed collection from the day before. Sue did her best, I did nothing at all. The day went by.

Chyamtang is way up north in Nepal, not far from the Tibetan border. It seemed to be a big village because many people kept coming and going by us. By many people, I mean perhaps twelve, but we had seen so few people in the last few days that five began to seem like a crowd. They passed through, they stared at Sue and me, and then they went on. At some point we had to take refuge in our tents, she in the one she shared with Bleddyn, I in the one I shared with Dan. A group of children had come by at lunchtime and stared at us as we ate. We grew uncomfortable and went into our tents. While we were in our tents, a large group of people gathered outside and one person would open the tent flap to show us to the other people. We had to call on Sunam, who spoke gruffly to them and made them move away. But nothing made my rest day not blissful. I was reading my book by Frank Smythe about his failed attempt to climb Kanchenjunga in 1930. Three weeks ago I would have had no interest or understanding of his account of climbing a mountain. I knew of him through his writing as a plant hunter. I had no idea that the mountaineer and the plant collector were the same person. Much later, I came to see that he became a plant collector because it was a way for him to climb mountains. His most famous book of plant collecting, The Valley of Flowers, is full of the many little side trips he took to climb some summit, insignificant by Himalayan standards but major when compared to the rest of the world’s geography. It became clear to me that while trying to climb Everest in the twenties, and then Kanchenjunga in the thirties, the spectacular beauty of a Himalayan spring left such an impression that it either made him a gardener or made him see those mountains as an extension of the garden.

On October 13, our day off, I lay in my tent alone reading. Sue, sick with a cold, dutifully got up and cleaned the seeds that Bleddyn and Dan had collected. I wasn’t very interested in this since none would survive in my garden. Dan had gone off in the direction of a village north of us, a village called Ritak, which Sunam said bordered Tibet and so he warned us against going there. Dan went off toward it just the same and said he would be careful not to wander into Tibet. Bleddyn had gone back toward Chepuwa. On this side of Chepuwa both he and Dan had seen a gulley that went up into a thickly forested area, and they were both sure that it was rich in pleasingly ornamental flower-bearing plants. That night, over dinner, they went back and forth regarding what to do, should they both go back to it or should they both go up to Ritak? Dan wanted to go to Ritak and so he did. Bleddyn went back toward Chepuwa and collected in the gulley above it. Dan went out of Chyamtang, crossed the Arun, walked on its banks for a quarter of a mile or so, and then re-crossed it on a bridge made of bamboo. At that point of its life, the Arun is closer to its source than when we first saw it in Tumlingtar. Near Tumlingtar, it is broad and majestic and even calm and forgiving, flowing in a dreamy way, making you long for a swim, lulling you into any kind of romantic thoughts you can have about calm and steady flowing water. But up near its source, it is fierce, roaring, as if trying to escape from an eternal dam. I had never seen water like that, so clear, so translucent, yet thick like a cloud. It looked as if you could see through it, but you couldn’t. Rushing furiously, scouring the earth, it was ready to take with it anything that stood in its path. To see this force, at that juncture about twenty feet wide and I do not know how deep, bridged by a structure made of bamboo, is among the most alarming things I have ever seen in my life. All of the other most alarming things I have seen in my life occurred not far from there. Dan crossed this bridge and went up to Ritak.

Bamboo bridge crossing a tributary of the Arun

The climb up to Ritak was steep, Dan said. When he got to the village some people mistook him for a doctor and asked him to come and take care of a man who Dan could see was near death. He didn’t know what was wrong with the man but he thought it might be some kind of cancer. Anyway, he left some Advil and tried to tell them he was not a doctor. Returning to Chyamtang at the end of the day, as he crossed the river over the bamboo bridge, without him knowing it, some boys had followed him. Suddenly, when he was midpoint on the bridge, the part of the journey over any bridge when you feel most vulnerable, the bridge began to shake and sway. Frightened, of course, he didn’t know which way to run, but then he heard some laughing and looked to see these boys jumping up and down on the Ritak side of the bridge. He arrived in camp at around half past three, looking exhausted. He had just seen a man dying and for a moment, on that bridge, he thought he was dying too. Not long after that Bleddyn returned too with a bounty of things, more than Dan had found in Ritak but with no encounters with other human beings. We all went to the little stream that was a quarter of a mile away and washed ourselves and our clothes, for suddenly it had been decided that we should take another rest day. It seemed that there were some valleys and ridges above us that the plant collectors wanted to explore.

Dinner that night was wonderful even though it was the same as all the nights before: soup, potatoes, rice and dahl, or noodles, one or other, sometimes all of them. It seemed as if all the people living in the area had descended on our camp and were just sitting and looking at us. It was as if we were a living cinema. They watched us eat and talk. Sometimes they peered at me and said things about me to Sunam, but of course when I asked him what they were saying, he suddenly did not understand the local language. One woman did make me understand that she thought I was wearing a mask, that my face was not my real face. She strangely, I thought, bore a strong physical resemblance to my own mother, who had been dead three years then. We saw a beautiful girl, who seemed perhaps eleven years old, perhaps thirteen, we couldn’t tell. She had just returned from tending a field about two thousand feet above us. We could tell this because she was wearing a beautiful primrose, blue, in her hair. Dan and Bleddyn kept trying to identify it. It was a primrose that bloomed in the fall, so they were not likely to find any seed for it.

In my sleeping bag at last, I fell asleep without worry for the first time in a week, without worrying that I would slip out of the sleeping bag and tent and fall down some ledge, for it was the first time since we left Num that we were camped on level ground; without worrying about leeches, without worrying about Maoists. It never ceased to amaze me how uneven the landscape was. A distance of a city block meant going up or going down, and though Dan, especially Dan, and Bleddyn took to it very well, the extremely uneven terrain was trying for Sue and me. I complained bitterly to myself, and quarreled with the ground as I trod on it, but even then I knew I was having the very most wonderful time of my life, that I would never forget what I was doing, that I would long to see again every inch of the ground that I was walking on the minute I turned my back on it. At around one o’clock that morning I came out of the tent to pee and met a black sky full of stars. Everyone was asleep, everything was quiet, once again I was struck at how far away I was from all that was truly familiar to me, but I didn’t long for anything; I felt quite lost and this feeling led to another feeling—happiness.

A third day of rest was called for and it coincided with the decision to explore the valleys above us. From Ritak, Dan had been able to see a forested ridge above Chyamtang and he thought if we could go above that, we would find things even I could grow. Bleddyn and Dan then argued over the way to get there. Dan had seen Bleddyn’s suggested route from Ritak, and since he did not like heights and did not like traveling along narrow ledges, he had ruled it out. Of course if he had been told that ripe fruit of the most unusual primrose or peony was to be had at the end of the most narrow ledge in the world, he would have lost his dislike for high, narrow ledges immediately. Also from Ritak, he had been able to see that the ledge ended and dropped off into nothing, empty air, not a route that led up above them. Sunam then made some inquiries and found a man who said that he knew most certainly of a way up from the ledge to the forests above. We took a lunch and with the man guiding us, Dan, Bleddyn, and I started out for the ledge itself, which was an hour’s walk up from our camp. I could soon see what Dan objected to. It was a narrow path, hardly big enough for one person, certainly it would be difficult to pass another person without their cooperation. I walked along clinging to the granite walls of the mountain, trying hard not to look down at the sheer nothing on the other side of me. The ledge took turns curving around so that we could not see what was coming and then jutting out so that we could see all too clearly how it snaked up. Still it was full of plants in seed, none of which would be hardy enough for me to grow, most of them mysterious, most of them new to me. But it was no place for the leisureliness of collecting, from Dan’s point of view, and so he and I turned back to camp, picked up Thile Sherpa, and set off for the same forests above Chyamtang but from another direction. That day, we walked up to ten thousand feet, the highest we had walked up in our nine days of walking. We crossed open sunbaked meadows, through deeply shaded and moist areas; we went down and up, but mostly it was up. Once when emerging from a forested area, I looked back and saw in the not too far distance, a gleaming white pyramid floating above the green-clad mountaintops that surrounded it. Kanchenjunga, I was told it was, the third-highest mountain the world, and it was less than twenty miles away. Each night before I fell asleep in my tent, I read Frank Smythe’s wonderful account of the failed attempt to climb this mountain in 1930, and among the thrills of reading it was becoming familiar with some people and a terrain between the pages of his book and outside the book, this at the same time. To now see this mountain that I had never paid attention to before I came to Nepal, so nearby, looking as if someone had just now placed it there a minute ago, left me openmouthed, in awe. I made Dan take a picture of me with it in the background, and when we started walking again, I kept looking back at it as if I was afraid I would never see it again. And I never did see it again, for when we came back down a great mass of clouds hid it from view, as they did for the rest of my time there. We saw blooming along the banks of the many streams we crossed the same beautiful primrose that we had seen decorating a girl’s hair but there weren’t any with seed. In that area, above Chyamtang, Dan and Bleddyn collected the seeds of so many things: Vaccinium, Anemone, another primrose, Thalictrum, Smilacina, Begonia oalmatumeuonymus, Codonopsis, clematis (species and Montana), Cardiocrinum, Gaultheria, Arisaema, Clerodendron (in many places its red fruit reigned dominant), Hypericum, Delphinium stapeliosmum, Rhododendron arboreum, Ophiopogon intermedius, Ligularia fisheri, Strobilanthes sp., Begonia sp., Jasminum humile, Sarcococca hookeriana, Pleurospermum sp., Cotoneaster microphylus, Gaultheria fragrantissima, Clematis sp., Holboellia latifolia, Meconopsis nepaulensis, Aconitum tuberosum, Rodgersia nepaulensis, Aralia cachemirica, Sorbus cuspidata, Roscoea auriculata, Hydrangea sp., Polygonatum cirrhifolium, Zanthoxylum nepalense, Hedychium sp., Lyonia sp., among many others, just to name some of them, but I was not so very interested because almost none of it would thrive in my garden, as Dan mockingly pointed out to me.

Author posing against the peaks of Kanchenjunga

Returning to camp, I did not see Kanchenjunga, but I enjoyed all the same the novelty of seeing a way I had come going in the other direction. On my journey, there was no coming and going, I was always going somewhere and everything I saw, I saw only from one direction, which was going forward, going toward, and then I was going away. So often I read in Frank Smythe’s The Kanchenjunga Adventure, of him going from a camp at one altitude to the other, and I came to see how comforting this back and forth in a strange place could be. It seems to me a natural impulse to begin to think of every place in which you find yourself for longer than a day as home, and to make it familiar. Dan and I descended more than twice as quickly as we had ascended, practically greeting the path as it wound through forest, pasture, over steep mounds, dividing a roar of water as it rushed to meet up eventually with the great Arun. How happy we were to see our tents there in the middle of the village, the only flat place for miles around, the only flat place until the next village, which was miles away. Cook had made a special dinner of rice with a special dahl and a cake even, but I couldn’t eat anything. I felt sick and so went to bed right away, and was asleep by eight. Much singing and carrying on was done late into the night, Dan said, by Sunam, Mingma, and Thile, and the porters. I awoke at two o’clock in the morning to silence and crept outside for my nightly pee. So soft everything was, in the blue-gray moonlight, the moon no longer completely full; how permeable the landscape looked, as if I could just walk through the hills and the trees, walk through them, not over them, as if they would yield.

In the morning we packed. We felt refreshed. We were beginning anew. We said goodbye to Chyamtang and it almost seemed like an act of rebellion or liberation. We were moving on. One of our porters, a fourteen-year-old boy named Jhaba Lama, came from this village. It was so fortuitous that when Sunam was hiring porters in Tumlingtar that Jhaba was there and was only returning home, not looking for work at all, and here was a job that would bring him to his home. The part of Nepal we were traveling in was not the part usually taken on a trek. Trekking paths usually make their way to a base camp at one of the high summits or around one of the nature-preserve areas attached to one of the high summits. So how fortunate for Jhaba that the path that would lead us to flowers went through his village. He was only fourteen, the same age as my son, Harold, and perhaps because I missed Harold so, I immediately singled him out for kind attention. When I told Sunam how touched I was by his presence, this little boy, the same age as my son, carrying sixty-pound loads strapped up on his back, he said of course I would be touched because Jhaba was a Sherpa. He did look like the people who come from Tibet. One day, when Jhaba had carried my bags, out of the blue I gave him a one-thousand-rupee note and I told him not to tell his fellow porters. When we arrived in Chyamtang, he went immediately to visit his family. That afternoon, his mother came to visit the camp and she brought us eggs and vegetables from her garden. She was a very beautiful woman with the same warm brown eyes as his, small and elegant. Sunam, who that time could understand her dialect, said that she thanked us for being kind to her son. Now, as we were leaving Chyamtang, we passed by Jhaba’s house and he wanted us to meet his father, who was a lama. It was clear they were an important family for their house was larger than the others and they seemed more prosperous in general. His father wore a long orange silk robe and had the general air of someone who spent most of the day reading and thinking about things judged to be important. He and Jhaba’s mother, whom we had already met, greeted us with just the right amount of warmth and distance. They made us wish we had met them earlier and so had seen them more, and yet they also made us feel that this was enough. I told them how wonderful their son was and, according to Sunam, they agreed and also said that their son did not like studying. We said our goodbyes and started on our way, down, down, down, on our way to crossing the Arun River for the last time. In Chyamtang we had been at 7,260 feet altitude. When we left the village that morning at half past seven it was seventy-seven degrees Fahrenheit. We crossed the Arun for the last time at an altitude of 5,620 feet. It was the highest point for a crossing we made of this river.