TOPKE GOLA

That night in the cold dark and snow when I had stumbled into camp, what I had missed seeing growing spectacularly among the boulders hovering above me was the great Rheum nobile, growing solitary, erect, aloof, and stiff like little sentinels. It was fall and they had long passed their bloom beauty, and so even now I would never see them in their true blooming glory. And why was I so awestruck to see it? I had never before seen it growing anyway. As far as I know, it cannot be found in any garden, certainly not in the garden of anyone I would know. In my life as a gardener, there have been a number of plants I have wanted to see, for the sheer unbelievableness of them: the blue poppy (Meconopsis benticifolia), Gunnera manticata (for its, literally, giant-sized leaves), just to name two of them. The Rheum nobile has been among them. I first saw the blue poppy many years ago growing in a display at the Chelsea Flower Show in England. My true delight and surprise proved very embarrassing to the people observing me; and I could not tell whether it was my ignorance or my enthusiasm. The Gunnera I saw in a garden out in the Pacific Northwest. That time, no one witnessed my delight and surprise. The Rheum nobile will only be found in books written by plant hunters and only ones who have been to certain areas of the Himalaya. There is a picture of it in flower to be found in Flowers of the Himalaya by Oleg Polunin and Adam Stainton. It is, as usual, solitary, growing in stark, rocky mountainsides, way above the tree line and surrounded by Meconopsis and some kinds of Primula. Its true flowers are hidden beneath large creamy yellow bracts—that are almost as big as its large leaves—and it stands around three feet high. What I was looking at then was its dried-up self full of seed. But neither Bleddyn nor Dan wanted to collect them because the conditions under which it will agree to bloom do not exist in an American or English garden. Bleddyn said that he had never even heard of anyone being able to make seeds of it germinate. It was while looking at the brown, dried sentinel, standing all alone among rocks, that I thought of the description Joseph Hooker made about this Rheum: “On the black rocks the gigantic rhubarb forms pale pyramidal towers a yard high, of inflated reflexed bracts, that conceal the flowers, and overlapping one another like tiles, protect them from wind and rain: a whorl of broad green leaves edged with red spreads on the ground at the base of the plant, contrasting in color with the transparent bracts, which are yellow, margined with pink. This is the handsomest herbaceous plant in Sikkim.” He was describing it in bloom. At first I saw only one dried sentinel and then as my eyes grew accustomed to the landscape, they appeared frequently enough but always somewhat far apart from each other.

The wonderful sighting of the R. nobile soon gave way to other things. It was near twenty degrees Fahrenheit when we left camp and crossed the blue, cold river along which banks we had spent the night. We were now heading to Topke Gola. We were in a rocky valley and going up. As usual, what seemed from a distance to be a point of termination, that is, the end of the road, was just another opening on to another vista. The boulders got bigger as we went up and the valley opened up wider too. We were now in the middle also of many rivulets, streams, tricklings of water burbling up and coming down. There were no trees here, just shrubby potentillas and junipers. The R. nobile was everywhere and so was another uncollectible, a plant called Saussurea. I had seen pictures of it, but before this, it held no interest to me. And now I understood why. The one I saw (and there are many others) was a white hairy mound, sprawled among the brown rocks and against a background of a very high snowcapped peak. So too we found other species of Meconopsis (discigera and bella) and primrose (stuartii), Rhodiola, Saxifraga (parnassifolia), Pleurospermum, lily (nanum), Geranium (nakonianum).

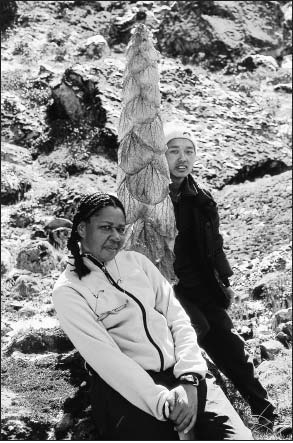

Author and Thile Sherpa beside a Tibetan Rhubarb plant, Rheum nobile

Left to ourselves, we would have been lost in this sea of rocks and boulders, for this landscape was as familiar to me as the one on Mars. Every obvious way to the pass that would then lead us to Topke Gola was the wrong path, and it was only thanks to Sunam, who whenever the going was difficult always brought up the rear, and the rear was Sue and especially me and my difficulties. And my difficulties were these: I found each plant, each new turn in the road, each new turn in the weather, from cold to hot and then back again, each new set of boulders so absorbing, so new, and the newness so absorbing, and I was so in need of an explanation for each thing, that I was often in tears, troubling myself with questions, such as what am I and what is the thing in front of me.

More than a few people have gone beyond the boundaries of the earth’s atmosphere and on returning, participate in parades and festivals and ceremonies with joy and enthusiasm. They have made the unknown normal-seeming immediately. It is just as well that none of these people were me. Had I been the first person to walk on the surface of the moon, I don’t think I would be able to speak for one hundred years afterward. As it is, I just went to Nepal on a plant-hunting, seed-collecting trek and the landscape at the foothills of the Himalayan mountains have left my tongue somewhat stilled, perhaps permanently so.

If someone had not shown me the correct path to go over the pass, I would not have found it by myself. I started up and it seemed friendly enough. I could still make out some growing things, the Saussurea was there, some gentian, and then much snow. I was now in that far distance that I could see from Num (at least the snow-covered peaks). I walked up and the snow got deep and icy and slippery. Of course, the top to the pass was farther than I thought, and the snow got deeper as I went up. The sun shone brightly and the light from the reflection was practically blinding. Halfway up, I could hear the sound of bells, and then soon a herd of yaks and their herder came into view. I had to make way for them, stepping out of the path, while at the same time making sure not to fall off into some bottomless depth that seemed ever nearby. I stood still, on the side as they passed, and then regained the path, only to hear the same sound of a caravan of yaks coming toward me again. This happened two more times and in a way they were a marvelous distraction. The herds were about seven yaks each, and each yak was decorated with bells and strings of wool dyed red, or white. The herders accompanying the yaks seemed not to notice us, or to pay any special attention to us. They did not look like any of the people I had seen before. They did not look like anyone we had met below the altitude of Thudam. From speaking to them, Sunam learned that they were carrying corn to Tibet and would return with rice and salt.

At the very top of the pass I stopped for a rest. It had taken us two hours to walk up to the pass and it had been a struggle for me. We were at an altitude of 15,600 feet. I felt exhausted, physically of course, but that I could handle. It was just that I felt emotionally so. I rested at the stupa, for there was one; and there were prayer flags too. There is the proper way to go around one, it is to the right; but I long ago could not understand what was the right way or the wrong way and I only hoped that the god of this place would look kindly on my ignorance, which only came from exhaustion. Sunam pointed out to me where I had just walked up and then he showed me something, a lake, a hidden lake that could only be seen from the pass. It was so unexpected, so pristine, so real and yet not so, that I felt as if I would dissolve. I did not. I made Dan take a picture of me with it in the background, and I do not know whether it was in consolation or confirmation that he told me the water in the lake eventually found its way to the Ganges.

Leaving the pass was like leaving a great book, which had yielded every kind of satisfaction that is to be found in a great book, except that with such a book you can immediately begin on page one again and create the feeling of not having read it before, even though the reality is you have read it before. How I wanted reaching the pass, going up to it and then leaving it behind, to be something like that, the reading of a great book, the texture of it, the rocks moving under my feet, the flowers that I could never cultivate all full of collectible seed, the precariously standing boulders, each one looking as if it was just about to roll down on top of me and only me; the six-inch deep snow, the slipping around in it and falling down at least once, the clearest of blue skies above me, the sun hot even though I was in the midst of cold and snow, the herd of yaks, the hidden lake, seen by so very few human eyes for all of its millions of years’ existence, its contents eventually joining up with the great Ganges. To make the experience like a book, here it is in a book I am writing now for myself. But it is very hard to do this, for each word I put in the book is a word I have had to part with, each experience I portray in this book is one I had to part with. I have not wanted to part with anything, word or experience, I have had while walking around the foothills of the Himalaya in Nepal among its flowers. The book I am writing and so therefore reading will soon be taken away from me. The chances of me going over that pass and seeing that lake hidden just below it again are practically nil. I shall go looking for seeds again and I shall go somewhere else.

Author and Dan Hinkley on the high pass between Thudam and Topke Gola

I walked down on the other side of the pass and it seemed to me not a mirror image of what I had just come up. But perhaps this experience was determined by my knees. Going up is hard on the lungs, going down is hard on the knees. I saw nothing growing on the way down for some time. The fact that the caravan of herders and yaks had an hour or so before been on the very path I was now on seemed unreal to me. There was no evidence of them. The mixed rock-strewn and boulder landscape appeared to me undomesticated, untouched even by human imagination. I do not say this with certainty. I state this with plain and unmodified ignorance. We walked away from the pass with desperation, and that does not seem to me now, as I write this, abnormal. Everything I have ever read about people going to passes, it appears that they go through them with some desperation.

As we walked down I began to see the isolated patches of gentians, so minute in the vast landscape that they seemed like colorful pebbles. And so too were the little croppings of Delphinium, six inches high at most, pale and hairy hoods of whitish, grayish blooms. They were in bloom and we were in the month of October. Where could we find seeds? But this is a plant so particular, it needs a certain amount of time covered with snow and then a certain altitude on top of that. It was another wonder to see, and it made me think of the great Alpine gardener who lives not too far away from me, Geoffrey Charlesworth, but I only thought of him, I do not know him. It also made me think of once going to a part of Glacier National Park, with my friend Ian Frazier, and walking in an Alpine meadow and seeing the plants that will grow on rocky soil, exposed to the harsh elements of sun and wind, thrive with abandon. The walk down was treacherous, each step seemed a passport to doom, a mix of rocks and boulders, as usual, but in this part of the world, the usual was always new. And then I noticed, there, something new: the rocks and boulders had darkened; the very openness of the sky had taken on a darker tinge, as if another dominance reigned.

We stopped for lunch in a sheltered part of the valley and the sun was hot, and there was no wind at all, and just as we were congratulating ourselves on how well everything was going a host of black clouds appeared on the horizon and they did not go away. They came toward us and we packed up and walked on. They hovered, not so much overhead but in the background, like some evil omen to come. We then walked along the edge of a landslide; that is to say, what might have been an easy path to walk on had fallen down, and for a short while I understood what was meant by a knife’s edge in the context of people walking on mountains. We walked to Topke Gola and again were in acres and acres of rhododendrons, all low growing, shrubby, and small leaved; and juniper, Salix, and of course Meconopsis (we were seeing it in abundance, the full-of-seed capsules of paniculata), and Arisaema jacquemontii (a plant in seed I found, but Dan had to tell me its exact identification). We walked through such a vast area filled with masses of small-leaved rhododendron that I was sure for a short time that there was no such place as Topke Gola. In this vast area covered with the small-leaved rhododendrons, there were some remains of camping sites, of campfires, and sleeping or outdoor habitation. And I then understood the herds of yaks that I had made way for coming over the pass. I was in the middle of a vast pasture. Everything that was a treasure to us in our gardens in Wales or North America was fodder in the life of yaks and the people who took care of and depended on them for sustenance. We walked through this wide and high valley, the mountains in the near distance (for by now everything far away was nearby and everything nearby was far away) and exhausted as if for the first time, without remembering that we had been exhausted before, and after a while we saw the hamlet of Topke Gola way in the distant. After the two nights spent in the forest, seeing a village with houses, and so therefore people and domesticity, seemed like a gift. And like a gift it held within it surprise, perhaps the essential, wonder, beauty, and mystery. I could see its brown structures, unsullied by paint of any kind, that were the dwelling places, huddled together, as if each one was a part of the other. From above and at thirteen thousand feet, the whole hamlet seemed so nearby, always so nearby, but it took one and a half hours from first seeing it to arriving there, and buildings that from far away seemed so small and insignificant were large and stairs had to be climbed to enter them. Not ever did I get used to this—the deceptive nearness of my destinations—not ever did I become accustomed to the vast difference between my expectation, my perception, and reality; the way things really are.

When I arrived at our campsite everything was all set up. We were a little village all by ourselves. Sunam, Thile, and Mingma seemed happy, I supposed it was because they had gotten us to Topke Gola safely. Their happiness made me love them, whatever that means now and especially then. It was decided we would spend two full days there. It was an area rich in flora to be grown in various temporal zones, certainly for people who made gardens and were prosperous enough to afford the plants that would be grown from the seeds collected here. The porters had built fires from twigs gathered from the junipers and rhododendrons, which were growing everywhere. It was as if they regarded the junipers and rhododendrons as weeds. But I am reminded again that every weed can be made into a treasure in the right circumstances. The junipers and rhododendrons being burnt for fuel then would be a treasure to many a gardener in the climate I am living in now, it would be a treasure in North America.

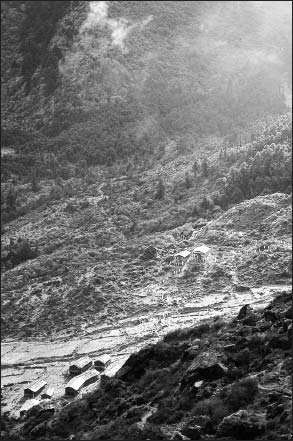

Village of Topke Gola

Seeing my pitched tent then, it was as if I was seeing my ancestral home, and I laid out my sleeping bag in it and crawled in. We were at three thousand feet lower than we had been at the pass and the whole day just passed not like a whole day at all but like many days, each part of the day so different, as if it were something in a View-Master, that child’s toy-way (at least it was a child’s toy when I was a child) of viewing scenes, every detail in one photograph, every detail contributing to a full realization of the picture, every picture being such a realization of what was real, that the real was always lacking. And so Topke Gola, seen from far away, was like a picture, but then when arriving in it, it had its problems: some people were living there and they did not come out to greet us, and the buildings that when seen from above had been so mysterious and full of promise, now nothing emerged from them. It was as if we had stumbled onto something that had been and yet at the same time was in the present. The hamlet was closed and yet the hamlet was completely accessible. I experienced it so.

We had a dinner of rice and dahl and potatoes and I had been noticing that over the last five days the potatoes had become impossible to eat. I had thought that Cook just grew tired of cooking potatoes and didn’t care whether they were worth eating or whether they were cooked properly or not, but Sunam explained to me that the potatoes were cooked in a pressure cooker and that the higher we got, the high altitude nullified the power of the pressure cooker to cook food thoroughly. It was just as well, for I went to bed, that is, I crawled into my sleeping bag, just as it got dark at half past seven. In truth, it felt like midnight. I left Dan and Bleddyn and Sue, cataloging and labeling and cleaning the collections made so far. Perhaps I was suffering from the altitude, but I felt nothing so much as tired, physically, of course, but also mentally for I needed one year, it seemed to me, to absorb all that I had seen that day alone.

Let me recount: I began on the bank of the blue glacial stream with Sunam’s special breakfast, I crossed it, walked up a valley filled with rocks and boulders that were the conductors of rivulets sometimes, streams sometimes, and then we were at the foot of the pass and we walked up that for two hours, making way for herds of yaks that were on their way to Tibet, and we saw a lake, discreetly placed away from the human eye, and then we walked down a ravine and into a rocky meadow, a grazing pasture for yaks, past masses of plants, each of them a treasure to grow in my garden if only they would allow themselves to do so, and then I walked into a hamlet, a fabled place, and I rested there. I went to bed and the next morning woke up to the ritual of all the other mornings: a basin of hot water brought to me by the assistant to Cook, a cup of hot instant coffee. I drank the hot beverage; I gave myself a sponge bath and got dressed and walked out of the tent I shared with Dan to breakfast. It took me a while to realize that my tent was cast on, that I had slept on, and that I was also walking on, an area in which Meconopsis (in particular paniculata) grew wildly.

After breakfast I did some housecleaning in our tent. The day was beautifully clear, the sun shining, the skies blue and cloudless. And yet there was a chill in the air that did not correspond to the bright sun and the clear sky. It was as if all three things existed apart from each other, one not an influence on the other. The sun could shine as brightly as it wished, in as cloudless a sky as there ever could be, and the air would remain a temperature that was not affected by any of that. I put out Dan’s and my sleeping bags, laying them out on some small-leaved rhododendrons and the juniper and berberis that grew everywhere. I put out also my dirty and worn-up clothes, hoping that exposure to the sunlight and the clean air would make them smell and feel better. I asked Cook to warm some water for me so that I could take a bath. He did and brought me the aluminum washbasin in which all our dishes were washed. He filled it up with water, hot and cold to make just the right temperature for a bath, and I washed myself using a bar of soap that I had taken from the expensive hotel when I had stayed overnight in Hong Kong on my way to Nepal, such a lifetime ago, or so it seemed. That was the bar of soap that we used to wash our hands before each meal, part of the ritual of being served our meals at a table that was always formally set with a tablecloth and knife and fork in their proper place. The soap had come in a blue box with the Tiffany label and the further away we got from anything resembling the idea of Tiffany and the luxury it represents, so did the soap become grimy and slimy from falling into dirt and being closed up in its expensive little soap box. Cleansed with the help of the by-now disgusting Tiffany soap, I put on my aired-out dirty clothes and felt wonderful.

Topke Gola, I could now see, was not a village or a hamlet, it was a place. Chyamtang had been a village, Thudam was a trading post, a crossroads connecting one place with the next. Topke Gola was a holy place. There was a monastery there and perhaps a Holy Man was in it. Sunam never said yes or no. He said, though, that in the summer many people lived there, that all the buildings are occupied then, but after that most people leave and only a few of them stay behind. He bought some yak meat from someone who had stayed behind and that night we had it for dinner, the first fresh meat we had eaten since we left Kathmandu. We were at a little under twelve thousand feet in altitude, four thousand feet below the altitude at the pass. Like all the other days before, what had taken place yesterday seemed like a dream. Topke Gola seemed like a dream too. Or perhaps another way of putting it, I felt as if I was looking at things through a sieve, not a transparency, but a surface with small holes in it. I could see the monastery, a small whitewashed building in a sea of brown. How did the whitewash get all the way up here? I wondered, but that was all I could do, for I got the impression that I shouldn’t go anywhere near it.

In Topke Gola, there was a sacred lake, a mile above the village, a destination for pilgrims who came to the village in the summer. I walked up to it. As usual in this place, I was in awe at the unexpected. How could I predict that there would be a body of water, a lake, not at all like the secret one seen from above the pass, that finds its way to the River Ganges? That lake, the one seen from above the pass, was so remote and it seemed as if it would remain so even if you found yourself sailing on it. It was as if, because it would become part of a body of water that was accessible to so many, it made itself available for viewing purposes to only a few. The Sacred Lake in Topke Gola on the other hand looked sacredly domesticated. A goddess is said to live there and in the temple, a beautiful little open-sided building situated at the entrance to the lake, were the remains of offerings, bone, branches, stones, and a small bottle of whiskey. On its banks were growing many things I desired as a gardener: rhododendrons, juniper, berberis, clematis, and so on. I turned away from this and walked back to our camp, exhausted, not from going to the Sacred Lake but from knowing that it exists. And why is that? Why not have that feeling from seeing the lake above the pass, that lake being a true secret? If someone doesn’t point it out to you, it will be missed altogether. I believe it is because seeing something that is hidden in the natural world makes me think not at all about myself, not about any one thing in particular; that a body of water situated in an area of the world with which I am not at all geographically familiar fills me with the joy of spectacle, the happiness that comes from the privilege of looking at something solely rare and solely uncomplicated. But the Sacred Lake plunged me into thinking of the unknowableness of other people.

Handwoven prayer rug in Topke Gola

Later that day, Sunam took me to a weaver, a woman who lived all year in Topke Gola and made prayer rugs by a handloom. I bought one and only after I got home to Vermont did I see that it was somewhat crooked, it had not been evenly woven.

Those two days and three nights spent in Topke Gola were perfect. The nights were cool and it rained then. The days were sunny, with the clouds dark and heavy with moisture or white fluffs of clouds without moisture, flitting hurriedly to some other destination. Sue and I stayed in camp and cleaned seeds, glad for the days of rest; Dan and Bleddyn went off to the mountains above and came back with treasures of seeds. The porters made fires from the wood of the treasured rhododendrons and junipers and berberis. They sang songs and made and ate their food along with us. I realized then, that I had no idea how or when they acquired or ate their food. They sat around with Sue and me and she taught them how to separate various seeds from their fleshy fruit. They knew nothing. Those three nights and two complete days seemed, even then, but more so now, as if they were the sole purpose of our journey. Everything collected there was growable in a Vermont garden. I was keenly aware of that. When coming down into Topke Gola that very first day, I had spied an Arisaema in seed and Dan had made a big show of it for he had been looking for it. And all the Meconopsis in our area were ones I could grow, if only I would learn to do so. Where I live, this is not the sort of plant you can just throw its seeds on the ground and wait to see what happens. We were surrounded by thousand-foot-high, green-covered mountainsides and above these were snowtopped peaks. Coming out of one side of the green-covered mountain was a fierce waterfall that looked, in its usual way, as if it had been painted on there, so constant was the force of its flow. But unlike the other waterfalls of this kind, the long white foam falling silently into an invisible abyss, this one was so close by its constant roar was unrelenting. Sometimes, due I suppose to some distortion caused by the wind or some other natural element, it sounded like the roar of jet engines. But if I had never heard the sound of jet engines, I do not know what I would liken it to. Those two days were like that, perfect and perfect again, unerring. When we had soup made of yak blood and then a stew of yak meat all in the same meal, it was perfect. When during the night and the next day, our stomachs ached in upset at this sudden change in our diet, which had been high in carbohydrates, it was perfect. No error at all, no complaints. What nights we saw: no full moon lighting up the star-filled sky now, just a part moon, the biggest spot of light in a deep navy blue sky, seeming motionless, wherever it appeared, just the way the earth we’re standing on seems motionless. I marveled again and again at how every time I stepped out of the tent Dan and I shared, I was walking on a carpet of Meconopsis paniculata. And then we left.

Our leave-taking perhaps began with our arrival. That first morning after we had arrived the night before, Jhaba Lama said goodbye to us and returned to his home in Chyamtang. He had agreed to be with us only as far as Topke Gola and at that juncture of our journey, Sunam had calculated that we would need less help. As things unfolded, he was correct. Sue and Bleddyn and Dan and I said goodbye to him and gave him a tip, a generous one, and we gave him that large of a tip because we thought he would take it home to his parents and make their lives a little easier, especially we were thinking of his mother. Immediately on receiving this large sum of money he bought a drum from another porter and began playing it with the biggest grin on his face, a grin that I took to express his own satisfaction at getting something he really wanted. All along the way, while we had been going to bed early and fretting through the night in one form of sleep or the other, the porters would stay up and drink and sing and dance to music they made. Someone had a drum, a small one that had to be held between the knees, and Jhaba Lama had liked the sound of it and he liked to dance to the sound of it. And so he bought the drum with his own money. He left us and would spend the night in Thudam and then reach his village, Chyamtang, the next day. He would make our four-day journey in two days.

We left Topke Gola, the place that had ten houses (I had counted them), and a sacred lake with a good amount of seeds, from which would come plants for gardens, at half past seven in the morning. It was cold, thirty-three degrees Fahrenheit, and some new snow had fallen on the mountain up above us. But we were not going up, we from now on would be going down. I did look around me one last time, not so much to say goodbye, for I feel, even now, that I shall go to that place again; I looked around for a last look with the thought that it would not be too long before I doubted that I had ever been in such a place.