The less effort, the faster and more powerful you will be.

—Bruce Lee, actor

A consultant with an inoperative computer is much like a taxi driver with his cab in the shop. Chip’s sick computer needed a particular part to get him back in business. Now, get ready to follow his experience with the hellish computer part replacement process.

A call to the computer manufacturer’s toll-free number led to an automated phone queue followed by a wait, followed by a “too-many-questions” service clerk, followed by a transfer and wait, followed by a tech support person, followed by a transfer and wait, followed by the correct tech support person, followed by a long wait, followed by the part arriving ground instead of overnight, followed by the part arriving broken.

So, how are you feeling? The super long sentence in the previous paragraph was crafted to demonstrate the customer’s side of the encounter. We have all been there. And, it reminds us that customer effort trumps just about every other service factor these days.

Convergys, a research company based in Cincinnati, Ohio, found that customers who rated their experience as satisfactory and easy were three times more loyal than those who simply stated they were “completely satisfied” with the experience. The Harvard Business Review reports in a study of more than 75,000 B2B and B2C customers that “When it comes to service, companies create loyal customers primarily by helping them solve their problems quickly and easily.”

We were conducting a series of focus groups for a large client to ascertain what service factors were deemed most important by their customers. One technique used was paired comparison. You can put twenty factors on a sheet of paper and ask respondents to rank order them. However, you get a far more accurate picture of priority if respondents are asked to look at each factor paired with every other factor to select which is more important. Applying a simple regression analysis to the data led to a true picture of customer preference. “Easy to do business with” was more important than smart people, empowered people, friendly people, accuracy, reliability, great service recovery, knows me and my needs, etc.

Focus groups enable a researcher to get underneath data to ferret out the meaning behind the responses—something a survey cannot accomplish. We wanted to learn what “easy to do business with” was really about in the eyes of these customers. We were confident that learning the “whys” behind the “whats” could surface a solution that dealt with the cause and not the symptom. What we learned was straight out of your Anthropology 101 textbook. Customers examined “service” effort through the lens of time, values, language, traditions, and symbols.

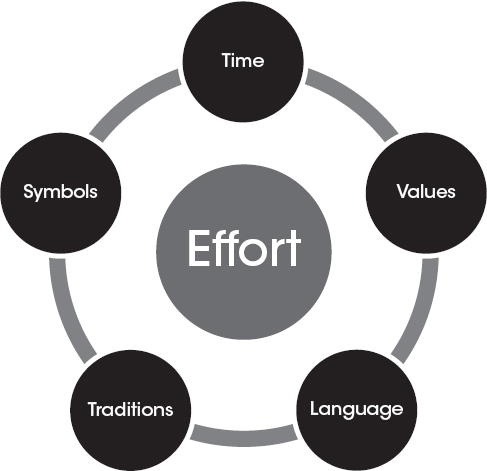

Social or cultural anthropologists study the dynamics of groups with a particular frame of reference. Just like a physician has a model of a “healthy body” in mind as he or she examines for gaps between what is and what should be, anthropologists attempt to understand a culture by considering their allegiances to time, values, language, traditions, and symbols. The mosaic provides a path to an enriched understanding (Figure 11-1).

Figure 11-1. Components of Effort.

Anyone who has traveled to the Caribbean learns quickly about being “on island time.” A feature of the island culture is to slow down. Customers also view effort in terms of time. When the customer feels the pace is slower than their service clock suggests it should be, it starts their satisfaction meter in the wrong direction. It means knowing the customer’s service clock and matching it.

Or, it means reframing their expectation of wait by altering their perception of time. Disney tells you the wait time in the queue for park rides—all set to be less actual time than posted time. They also entertain us as a means to alter our perception of wait. A branch bank polls its lobby customers on what they prefer to watch on the television monitor viewable from the teller line should the line get longer than expected. Find out what time means to your customers and manage that part of effort that is exacerbated by disappointments around time.

Cultures have always been defined in part by what is valued by their people. Customers are no different. And, while all customers are different, they share certain core values. Queues in airports, restaurants, and the Department of Motor Vehicles are generally orderly without pushing and shoving because of a shared value of fairness—as in, “no cutting in line” and “first come, first served.” We expect folks in first class to get better food than airline passengers in coach. And, as passengers, we also know that first class seats are the result of frequent-flyer loyalty or the price of the ticket and not due to any socioeconomic, gender, or racial factors.

Effort is also a critical component of value. The recession has elevated customers’ standards for the level of effort they will tolerate before becoming unhappy. Pay attention to dissonant messaging. When customers hear, “Your call is very important to us” followed by another message that says, “Your wait time is approximately thirty minutes,” they do not interpret it as rude; they see it as a bold-faced lie. A business that closes earlier than what is posted on the front door or a computer part promised overnight that is shipped ground crosses the value line for customers and spells deception, not bad manners. Make certain you know the true meaning of values related to service among your customers. Just guessing or assuming “they are just like me” will lead you astray.

Language is not just about communication—with its idioms and slang. It is about how meaning is transmitted from brain to brain. And, the mental pictures created by the words chosen are fraught with the potential for inaccuracy and misinterpretation. The conduit that drives the picture exchange hangs on effective and caring listening. So, how good are service providers at really listening? According to Convergys research, 45 percent of customers think companies do not have a good understanding of what their customers really experience when dealing with them. Yet, 80 percent of employees and executives think they understand.22 How could that be?

When resource-strapped employees are placed in a listening role—whether face to face or ear to ear—the risk of misinterpretation and error soars. It results in employees focusing on the task, not the solution, and robotic adherence to policies and procedures rather than effective problem solving. It also results in undue effort by customers who are forced to emote, evade, echo, or escalate just to get what they want. Make great listening a vital part of the organization’s DNA. And, remember the ancient line, “You are not eligible to change someone’s view until you demonstrate you understand his or her view!”

Traditions are the customs, mores, and habits shared by a society. For instance, Western culture is keenly concerned with human rights and equal opportunity, whereas other cultures are not. Customers also share a set of mores. As customers, we expect service to be a form of assistance. We assume we will be treated with respect. We anticipate a service provider will be there when we need them and in the form that we require. Excess effort surfaces when the practice of service fails to jive with the expectancy of service.

Today, customers expect access around the clock, not just from nine to five, Monday through Friday. While they enjoy the access and time-saving aspect of self-service and automation, when it fails to work, customers feel abandoned and devalued unless given an easy, quick back door to a person. They assume service will be crafted to fit their needs and they will not be shoehorned into a service delivery process without flexibility. They expect a wide array of choices and abhor any offering that is solely “one size fits all.” This means that the perfect customer experience requires knowing what customers expect and ensuring the traditions of service match their requirements.

Few things characterize a culture more than the symbols it employs. Most Americans above the age of five can correctly identify Abe Lincoln, the American eagle or flag, the Statue of Liberty, or Uncle Sam. Symbols make us feel secure and reduce the anxiety of uncertain situations and encounters. They are the emotional sign posts that help us feel a sense of belonging. Customers use symbols for many of the same reasons.

Effort surfaces when the signals of service send a different message than customers anticipate. When John Longstreet (now CEO of Quaker Steak and Lube) was general manager of a large hotel, he set up periodic focus groups with the taxi drivers that transported his guests to the airport after their stay. He learned about subtle symbols derived from the guests’ sights, sounds, and smells rarely found on a guest comment card. Missing toilet items signaled poor accuracy; scorched-smelling towels implied the potential for a hotel fire; and a poorly lighted parking lot brought worries about safety in hotel hallways.

When famed anthropologist Margaret Mead first visited Samoa in the South Pacific, it led her to write in the preface of her book Coming of Age in Samoa, “Courtesy, modesty, good manners, conformity to definite ethical standards are universal. . . . It is instructive to know that standards differ in the most unexpected ways.” Her nonjudgmental approach to the target of her research enabled her to gain a level of intimacy with Samoan inhabitants that few researchers had been able to attain.

There are many components in the social encounter we call service. As service providers, how can we be effective at learning precisely how time, values, language, traditions, and symbols are embedded in our customers’ experiences? We can take the Mead approach—nonjudgmental recognition that customer “standards differ in the most unexpected ways.” How are you gaining customer insight into your customers’ anthropology? How can you utilize that customer intelligence to remove and manage service effort?

Anthropology demands the open-mindedness with which one must look and listen, record in astonishment and wonder that which one would not have been able to guess.

—Margaret Mead