The ongoing story of electric aviation as a love-hate relationship between mythology and hard scientific fact goes back a very long way. Let us enjoy some mythology first.

While the sun god Aton (14th century BC) proclaimed by the monotheistic Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaton is depicted as a solar disk emitting rays of light terminating in human hands, certain images sculpted by ancient Egyptians between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago might, according to some, suggest their knowledge of both airplanes and electricity. A unique group of hieroglyphs found in Sethi I’s temple in Abydos, Egypt, are said to depict nothing less than a helicopter, a submarine, a glider, and another unknown type of aircraft among the usual insects, symbols and snakes. The initial carving translates to “He who repulses the nine [enemies of Egypt].” The rational explanation is these images were created by a startling coincidence—two overlaid Pharaoh names, Sethi I and Ramses II. As time went by, the plaster came off, and the pictures were created by accident. There is no ancient technology here.

A 6-inch wooden artifact with a bird’s head, dating back 2,000 years and discovered in 1898 during excavation of the Pa-di-Imen tomb near the Saqqara Pyramid in Egypt, presents both a wing and a vertical tail fin more akin to those of a glider than a bird. Furthermore, the hieroglyphs on the “model” airplane read “The Gift of Amon,” and three papyruses found near the artifact include the phrase “I want to fly.” Egyptian physician Khalil Messiha has claimed that the Saqqara Bird has aerodynamic qualities and that the only thing missing is the tail wing stabilizer. To support his claims, Messiha built a balsa wood model six times the size of the original and added the tail, surprised to see that the model indeed could fly. Recent tests in modern wind tunnels have validated Messiha’s test. In spite of these claims, however, no full-scale ancient Egyptian aircraft have ever been found, nor has any other evidence suggesting their existence come to light.

Elsewhere in the Hathor temple at the Dendera Temple complex, three stone reliefs depict what appear to be electric lights linked to a text proposing “high poles covered with copper plates.” Critics suggest these images do not relate to electricity or lightning, pointing out that no evidence of anything used to manipulate electricity had been found in Egypt. They suggest that this was a magical and not a technical installation.

The Ark of the Covenant (in Hebrew: תירִבְּהַןוֹראָ ʾĀrônHabbərît), also known as the Ark of the Testimony, was described in the Book of Exodus as containing the two stone tablets of the Ten Commandments. Built in Sinai about 1400 BC by Bezalel, son of Uri, son of Hur, it served as a portable temple used during the Exodus in the desert and then the conquest of the land of Israel. It was made of acacia wood covered with gold, with two winged cherubim, one at each end. The Bible states that the Ark was carried on poles inserted in rings at the four lower corners carried by strong men from the tribe of Levi.

There is, however, a theory that it was able to levitate vertically and then move horizontally through the air; that its design was well known to match that of an electric capacitor, its wood being the perfect insulator between two charged plates of gold. In addition, the Ark was infamous for its deadly energy discharges. Those unqualified to touch, approach, or even look at the Ark would be struck dead. In this way, the following narrative becomes ambiguous: “And they departed from the mount of the LORD and the ark of the covenant of the LORD went before them in the three days’ journey, to search out a resting place for them.”1 In addition, God’s presence is frequently seen in the guise of a cloud in the Bible (Ex. 24:16). He appeared as a pillar of cloud (Exodus 33:9) and the Ark is constantly accompanied by clouds. When God spoke from between the Cherubs, there was a glowing cloud visible there (Ex. 40:35); when the Jews traveled, they were led by the Ark and a pillar of clouds (Num. 10:34). Was this pillar some form of aircraft?

It has again been suggested that the Biblical prophet Ezekiel (Yechezkel), living in Babylon around 800 BC, witnessed the arrival of an electric flying machine:

And I looked, and, behold, a whirlwind came out of the north driving a great cloud, and whirling fire surrounding it, with the gleam of polished brass (chashmal) in the center of the fire. Now as I looked at the living beings, behold, there was one wheel on the earth beside the living beings, for each of the four of them. The appearance of the wheels and their workmanship was like sparkling beryl, and all four of them had the same form, their appearance and workmanship being as if one wheel were within another. Whenever they moved, they moved in any of their four directions without turning as they moved.…”2

In modern Hebrew, “chashmal” למַשְׁחַ means electricity.

Staying with pseudo–Biblical legends, one elaborated across the ages has it that the Queen of Sheba gifted King Solomon a green and gold flying carpet sixty miles long and sixty miles wide studded with precious jewels, as a token of her love. It is said that a flying carpet was woven on an ordinary loom, but its dyes held spectacular powers. These were made from a special type of iron-rich clay procured from mountain springs and untouched by human hands. The clay was superheated at “temperatures that exceeded those of the seventh ring of hell” in a cauldron of boiling Grecian oil, and then acquired antimagnetic properties. So impregnated, the superconducting carpet, at an altitude of several hundred feet, could fly anywhere by following both the thermal air currents and the trillions of magnetic lines crossing the Earth from the North to the South Pole. When Solomon sat upon the carpet he was caught up by the wind, and sailed through the air so quickly that he breakfasted at Damascus and supped in Media.3

Known manuscripts of the Arabian One Thousand and One Nights date back as far as the ninth century. One of these relates how Prince Husain, the eldest son of the Sultan of the Indies, travels to Bisnagar (Vijayanagara) in India and buys a magic carpet. This carpet is described as follows: “Whoever sitteth on this carpet and willeth in thought to be taken up and set down upon other site will, in the twinkling of an eye, be borne thither, be that place near at hand or distant many a day’s journey and difficult to reach.”4

The Royal Library in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. It was dedicated to the Muses, the nine goddesses of the arts. It flourished under the patronage of the Ptolemaic dynasty and functioned as a major center of scholarship from its construction in the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 B.C., with collections of works, lecture halls, meeting rooms, and gardens. According to a Jewish scholar named Isaac Ben Sherira, this library also kept a large stock of flying carpets for its readers. The carpets were handed out, traded for the visitor’s slippers, and used to glide back and forth, up and down, among the shelves of papyrus manuscripts. The library was housed in a ziggurat that contained forty thousand scrolls of such antiquity that they had been transcribed by three hundred generations of scribes. The ceiling of this building was so high that readers often preferred to read while hovering in the air. The manuscripts were so numerous that it was said that not even a thousand men reading them day and night for fifty years could read them all! … except, that this wonderful tale, including Isaac Ben Sherira, is the fictitious elaboration of Pakistani-Australian author Azhar Ali Abidi in his The Secret History of the Flying Carpet, published as recently as 2002 AD.

It was in the 4th century AD that the first concept of rotary-wing aviation came from the Chinese. A book called Pao Phu Tau (also Pao Phu Tzu or Bao Pu Zi, 抱朴子) tells of the “Master” describing flying cars (feichhe) made from wood from the inner part of the jujube tree with ox-leather straps fastened to returning blades that set the machine in motion (huancheiniyhichhi chi). This is the first recorded evidence of what we might understand as a helicopter.5

Such myths only show how from very long ago, man desired to ride around in the air. These myths, long after this book has been printed, may well become daily reality.

In 1410, Le Livre de bonnesmoeurs (Book of Morality) was presented to the Duke of Berry by an Augustinian monk, Jacques Legrand. Towards 1490, an artist from the Valley of the Loire decorated a copy of this work with 53 miniatures. One of these shows a pregnant woman turning a vertical wheel, and above whom hovers a golden disc. At virtually the same time, Domenico Ghirlandaio of Florence, Italy, painted his The Madonna with Saint Giovannino in which Mary the mother of Jesus looks down while in the background a man on a ledge blocks the sun with his hand and stares at the strange flying object in the sky. By his side is a dog also looking up with its mouth slightly open. The object appears as a dark oval structure with light rays projecting out from all angles. When Aert de Gelder of Amsterdam painted the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist, instead of the Spirit of God descending as a traditional dove as he appears in hundreds of depictions of this event, de Gelder painted an oval object beaming down rays of light.

Who was indeed the first to fly using electricity? Reference might be made to one tale from Greek mythology, recounted by Pseudo-Apollodorus of Athens in his Epitome of the Biblioteca, a compendium of Greek myths and heroic legends, arranged in three books, generally dated to the first or second century AD From Epitome 1:

On being apprised of the flight of Theseus and his company, Minos shut up the guilty Daedalus in the labyrinth, along with his son Icarus, who had been borne to Daedalus by Naucrate, a female slave of Minos. But Daedalus constructed wings for himself and his son, and enjoined his son, when he took to flight, neither to fly high, lest the glue should melt in the sun and the wings should drop off, nor to fly near the sea, lest the pinions should be detached by the damp. But the infatuated Icarus, disregarding his father’s injunctions, soared ever higher, till, the glue melting, he fell into the sea called after him Icarian, and perished.

Modern physiological research suggests that electrical signals from Icarus’s brain, during his attempt to fly, were telling his shoulders and arms to flap, even if in his case solar energy proved destructive. Similar electrical signals would be used by flying horses such as Pegasus and the whole world of birds, bats and insects, currently being observed and copied with the biomimicry-inspired drones of the 21st century. Daedalus was not a mythological figure; he was an aeronautical designer, one of the engineers of Knossos. They constructed water-chutes in parabolic curves to conform exactly to the natural flow of water—streamlined chutes. Streamlining could only be produced by long years of scientific development and is an essential part of aerodynamics, which Daedalus must have mastered.

In 1505, Leonardo da Vinci, the Italian polymath genius, took a new notebook and began writing down in his coded reverse script observations of bird flight, the nature of air and flying machines. This Codex on the Flight of Birds runs to more than 35,000 words with 500 margin sketches. Leonardo noted: “A bird is a machine working according to mathematical laws. It lies within the power of man to reproduce this machine with all its motions, but not with as much power…. Such a machine constructed by man lacks only the spirit of a bird, and this spirit must be counterfeited by the spirit of man.”6 Leonardo makes such observations as how the tips of a bird’s feathers are always the highest part of the bird when its wings are lowered, and how the bones in the wing are the highest part of a bird when its wings are raised. Later on he begins to examine how bird flight could be applied to a man-carrying machine.

Eight years later, while staying in the Vatican, Leonardo predicted how humanity would use the sun’s energy. In a series of notes scribbled on blue paper he draws and describes “a pyramidical structure which brings so much power to a single point that it makes water boil in a heating tank like they use in a dyer’s factory.”7

Mythical stores of flight continued into the modern era when in the 1620s, Francis Godwin, Bishop of Hereford, wrote a Utopian-style book, The Man in the Moone, or a discourse of a voyage thither. He was inspired by the swans that regularly flew low above the River Wye beside his cathedral. In his book, the hero, Domingo Gonsales, flies to the moon in a chair pulled by the gansa, a species of wild swan able to carry substantial loads. Gonsales discovers the gansa on the island of St. Helena, and contrives a device that allows him to harness many of them together and fly around the island. Gonsales resumes his journey home, but his ship is attacked by an English fleet off the coast of Tenerife. He uses his flying machine to escape to the shore, but once safely landed he is approached by hostile natives and is forced to take off again. This time his birds fly higher and higher, towards the moon, which they reach after a journey of twelve days. The Man in the Moone was first published posthumously in 1638 (John Norton, London) under the pseudonym of Domingo Gonsales and enjoyed a popularity across Europe. By the second edition (1657), the pseudonym had been replaced by “F.G. B. of H.” (“Francis Godwin, Bishop of Hereford”).

There were those reputed to have used mechanical means to make an object fly. Johannes Muller von Konigsberg was a German mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and inventor who also frequently went by the Latin pseudonym Regiomontanus when he published his works. In the early 1500s Regiomontanus is said to have built an eagle out of wood and metal, and having fitted it with the cogs and wheels of clockwork, to have it fly out of the city of Nuremburg to greet the Holy Roman Emperor, then fly back again!8

But there were some seriously interested in magnetic effects and their use in flight. William Gilbert, the royal physician to Queen Elizabeth I, devoted much of his time, energy and resources distinguishing the magnetic effect of the lodestone from static electricity produced by rubbing amber, which he named “electricus.” In his book, De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de MagnoMagneteTellure, published in 1600, Gilbert invented a terrella (Latin for “little earth”), a small magnetized model ball representing the Earth. This gave rise to all sorts of fanciful theories which were published in The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, including speculations about flying chariots.

In 1709, Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão, a Portuguese priest and naturalist, presented a petition to King João V of Portugal, seeking royal favor for his invention of an airship, in which he expressed the greatest confidence. Gusmão wanted to spread a huge sail over a boat-like body like the cover of a transport wagon; the boat itself was to contain vacuum tubes through which, when there was no wind, air would be blown into the sail by means of bellows. The vessel was to be propelled by the agency of magnets, which were to be encased in two hollow metal balls. However, the public test of the machine, which was set for June 24, 1709, did not take place.

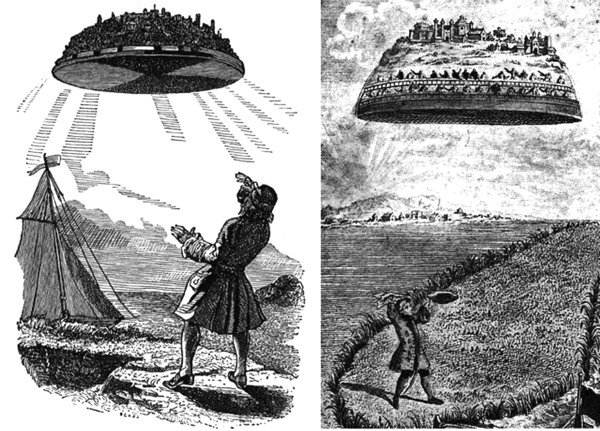

One book dared to poke fun at such projects: Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, commonly known as Gulliver’s Travels, is a prose satire by Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift. It was published in 1726 and amended in 1735. In Part Three, “A Voyage to Laputa,” Gulliver sees:

…a vast Opaque Body between me and the sun, moving forwards towards the island; it appeared to be about two Miles high, and hid the Sun for six or seven minute … the Reader can hardly conceive my Astonishment, to behold an Island in the Air, inhabited by Men, who are able (as it should seem) to raise, or sink, or put into a Progressive Motion, as they pleased. At the Center of the Island there is a Chasm about fifty Yards in Diameter containing at bottom a dome extending 100 yards into the adamantine surface. This dome serves as an astronomical observatory.… The greatest Curiosity, upon which the fate of the Island depends, is a Loadstone of a prodigious size, in shape resembling a Weaver’s Shuttle. It is in length six Yards, and in the thickest part at least three Yards over. This Magnet is sustained by a very strong Axle of Adamant passing through its middle, upon which it plays, and is poised so exactly that the weakest Hand can turn it.… By means of this Loadstone, the Island is made to rise and fall, and move from one place to another. For, with respect to that part of the Earth over which the Monarch presides, the Stone is endured at one of its sides with attractive Power, and at the other with a repulsive. Upon placing the Magnet erect with its attracting end toward the Earth, the Island descends; but when the repelling Extremity points downwards, the Island mounts directly upwards. When the Position of the Stone is oblique, the Motion of the Island is too. By this oblique Motion the Island is conveyed to different Parts of the Monarch’s Dominions.

Swift therefore entered into science fiction when he described this dome-shaped airplane which could fly around the kingdom using a lodestone. Magnetic levitation? He adds that is the custom of the inhabitants to throw rocks down at rebellious cities on the ground. Aerial bombing? While at the Grand Academy of Lagado, great resources and manpower are employed on researching completely preposterous schemes such as extracting sunbeams from cucumbers. Solar power?

But some scientists produced real effects. On January 20, 1746, Pieter van Musschenbroek of Leyden University’s Theatrum Physicum announced in a letter to the Paris scientist René Réaumur that he had come up with a technique using linked jars of storing the transient electrical energy which could be generated by friction machines. The letter, written in Latin, was translated by the scientist-clergyman Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet, who named it the “Leyden jar.” The name stuck. On page 46 of his book L’Essai sur l’Electricité des Corps, published in Paris by Frères Guerin, Abbé Nollet recounts how he first sent a discharge from a Leyden jar through a company of 180 soldiers holding hands. This demonstration was before King Louis XV at Versailles. The King was both impressed and amused as the soldiers all jumped into the air simultaneously when the circuit was completed. The King requested that the experiment be repeated at the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris. So Nollet next gathered about two hundred Carthusian monks into a circle about a mile (1.6 km) in circumference, with pieces of iron wire connecting them. He then discharged a battery of Leyden jars, which had been charged from a glass globe design of a generator, through the human chain, and once again observed how the monks, swearing and contorting, physically jumped into the air like one man, in sharp response to the discharge from the Leyden jars.9

In Part Three of Jonathan Swift’s satire Gulliver’s Travels, published in 1727, Laputa is in fact a floating island, powered and directed by a magnetic lodestone—or in other words, an electrically propelled airship (Wikimedia).

Maybe the first practical experiment with a flying object and electricity is reported to have been made in 1750 by Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia with his kite in a thunderstorm. According to the legend, during the thunderstorm, Franklin kept the string of the kite dry at his end to insulate him while the rest of the string was allowed to get wet in the rain to provide conductivity. A key was attached to the string and connected to that latest technology, a Leyden jar, which Franklin assumed would accumulate electricity from the lightning. The kite wasn’t struck by visible lightning (had it done so, Franklin would almost certainly have been killed), but Franklin did notice that the strings of the kite were repelling each other and deduced that the Leyden jar was being charged. He reportedly received a mild shock by moving his hand near the key afterwards, because as he had estimated, lightning had negatively charged the key and the Leyden jar, proving the electric nature of lightning. Fearing that the test would fail, or that he would be ridiculed, Franklin only took his son William to witness the experiment, and then published the accounts of the test in the third person. It was Franklin who coined the word “battery” and assigned a positive sign (+) for a gain in electricity and a negative sign (–) for a loss of electricity.10

In 1774, Abbé Pierre-Nicolas Berthelon, Professor of Experimental Physics for the States of Languedoc in Montpellier, a friend and admirer of Franklin, sent up a number of paper kites, to which he had attached pieces of metal, long and narrow, and terminating in a cylinder of glass, or other substance suitable for the purpose of isolation. In this way, he obtained sufficient electricity to demonstrate the phenomena of attraction and repulsion, as well as electric sparks.

In northern France, in 1775, Louis-Guillaume de Lafolie, a physicist and chemist of the Academy of Rouen, annoyed his fellow members when he published a novel he called La Philosophe sans pretention ou l’Homme rare. Ouvrage physique, chymique, politique et moral, dédié aux savants (The Unassuming Philosopher or the rare Man. A physical, chemical, political and moral work, dedicated to scientists) (Paris: Clousier). During this period, de Lafolie’s fellow academicians were trying to distinguish scientific fact from fiction. So to write a tale, told by an Arab about Scintilla, a former resident of the planet Mercury, who narrates her experience of space flight in an elaborate, newly invented ship which she has crash-landed on Earth, was bound to upset them as much as Jonathan Swift had upset the Royal Society of London.

De Lafolie wrote: “I imagined a machine with wings.… But what was my surprise when arriving on the platform, I observed two glass globes three feet in diameter, mounted above a small convenient enough seat. Four wood studs covered with glass plates supported these two globes. The lower room that served as base support and the seat was a camphor-coated tray and covered with gold leaf. The whole was surrounded by metal.” De Lafolie was suggesting that his fictional flying contraption would be powered by static electricity, produced when, using a system of hand-cranked wheels, its two glass globes were rubbed together, their powerful light changing the air pressure and enabling the alien operator to navigate. In 1705, Francis Hauksbee of London had demonstrated a glass globe (that could be evacuated) rotated rapidly by a pulley and rubbed with the hand became electrified, allowing various observations on electrostatic attraction and repulsion and on electrical discharges in a vacuum. By the 1770s such frictional machines had become very popular for electrostatic therapy. Strange that the Mercurian flying machine did not use Leyden jars.

In 1779, de Lafolie made amends for his planetary fantasy when he invented a varnish composition suitable for protecting copper-plated ships from the corrosive effects of seawater. He had been appointed Inspector of the Royal Factories by King Louis XVI, in recognition of his laborious and useful works, when he died at forty-one, following a slight injury that he suffered when a chemically charged flask he was holding in his hand shattered.

“La Fumée Electrique” (“Electric Smoke”) was the phrase erroneously used by the Montgolfier brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne, to describe the hot smoky air which, in the summer of 1782, raised their pioneering balloons to a height of 300 m (980 ft.) into the skies above Annonay, in France’s Ardeche region. The brothers had begun experimenting with balloons made of paper and early experiments using steam as the lifting gas were short-lived due to an effect on the paper as it condensed. Mistaking smoke for a kind of steam, they began filling their balloons with hot smoky air which they called “electric smoke.” The French Academy of Sciences soon invited them to Paris to give a demonstration.

In 1775, Louis-Guillaume de Lafolie, a physicist and chemist of the Academy of Rouen, published a tale about the visit to Earth by Scintilla from the Planet Mercury in a space ship powered by static electricity generated by rubbing two globes together (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

On December 12, 1783, Horace-Bénédict de Saussure published a letter in the Journal de Paris to prove that, “contrary to what scientists are thinking, it is not the ‘lightness’ of this air pushing up aerostatic machines; but the air rarified by the heat of the flames. The evidence is very easy to check: by introducing a piece of metal white hot in a paper bag, it is easy to propel it to the ceiling. The strong smell of electrical smoke remains!” In a letter he sent from Geneva on March 26, 1784, de Saussure mentions his having made some experiments on atmospheric electricity, with a tethered aerostatic machine, which, raised by means of the combustion of spirits of wine, was fastened to a long string. Although it was a cloudy day, he obtained a positive electric charge strong enough to create sparks.

Some fourteen years before, a young Italian called Alessandro Volta had written a treatise On the forces of attraction of electric fire (De vi attractive ignis electrici ac phænomenis independentibus) in which he put forward a theory of electric phenomena. His fame soon spread, and in 1781–1782, Volta, inventor of the electric pile or battery, traveled to Switzerland, Alsace, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Paris and London.11 The Montgolfiers most surely had heard of Volta when they used the phrase “electric smoke.”

In 1783, Benjamin Franklin, then living in Passy as Commissioner for France, had witnessed a Montgolfier ascent above the gardens of the King’s hunting lodge in the Bois de Boulogne, on the outskirts of Paris. Of this, he made the following general observation in a letter recounting the Montgolfier Brothers’ demonstration to the president of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, dated July 27, 1783: “I am pleas’d with the late astronomical Discoveries made by our Society. Furnish’d as all Europe now is with Academies of Science, with nice Instruments and the Spirit of Experiment, the Progress of human Knowledge will be rapid, and Discoveries made of which we have at present no Conception. I begin to be almost sorry I was born so soon, since I cannot have the Happiness of knowing what will be known 100 Years hence!” Franklin believed hot-air balloons “to be a discovery of great importance, and one which may possibly give a new turn to human affairs. Convincing sovereigns of the folly of wars may perhaps be one effect of it; since it will be impracticable for the most potent of them to guard his dominions.”12 But Franklin made no specific statement about the potential application of electricity to human flight.

On July 18, 1803, a Voltaic pile and an electrometer were taken aloft for five hours in a Montgolfier balloon high above Hamburg to measure the existence or nonexistence of electrical matter. The experiment was organized by a Belgian physicist and keen balloonist called Etienne-Gaspard Robert, otherwise known as “Robertson” or “Arago,” and his assistant L’Hoëst. In his nacelle, Robertson had taken “a Voltaic pile composed of sixty couples, silver and zinc; it worked very well when we started and gave, without condenser, one degree to the Volta electrometer. At our greatest altitude, the pile was giving no more than 5/6th of a degree to the same electrometer. The galvanic light seemed to me far more sensitive than on the ground; this effect appears contradictory.” The following year, Robertson proposed his plans for the Minerva, “an aerial vessel destined for discoveries, and proposed to all the Academies of Europe.” He dedicated his project to none other than Alessandro Volta. It would be propelled by sails, but was never built.13

Flight inspired great poets. In 1835 Queen Victoria’s Poet Laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in his poem “Locksley Hall,” wrote a passage called “Prophecy”:

For I dipt into the future, far as human eye could see,

Saw the Vision of the world, and all the wonder that would be;

Saw the heaven fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales….

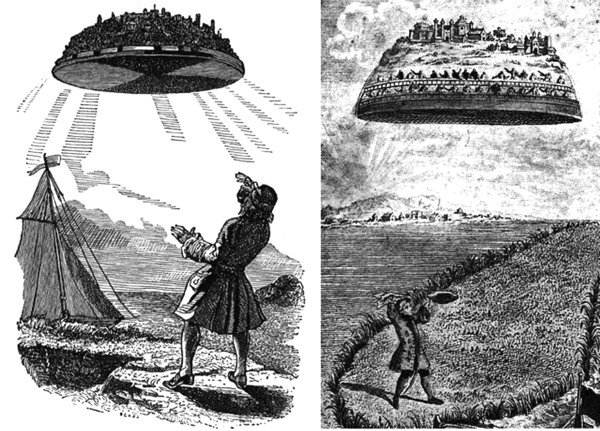

One electrochemist who was passionate about aviation was John Stringfellow of Chard, Somerset, England. In 1856 Stringfellow, who earned his money making bobbins for the local lace-making industry, patented what he called his Electro-Voltaic Pocket Battery, a device measuring only 3 in × 4 in, to be used to treat a whole range of medical ailments. If Stringfellow had subscribed to a publication called The Annals of Electricity, Magnetism and Chemistry, in the April 1837 edition, he may have read how his fellow countryman William Sturgeon had succeeded in propelling a boat and also a locomotive carried by the power of electromagnetism. But Stringfellow’s prior passion was flight, and the same year, he and his associate William Henson had planned a monoplane powered by the latter’s patented lightweight steam engine, not with a series of his own pocket batteries. The first hop of the 10-foot wingspan Aeriel, achieved in a lace factory, gave them the confidence to form the Aerial Transit Company to raise money to construct a 50-foot wingspan Aerial Steam Carriage, which would take people to exotic locations like Egypt, India and China; in short, an airline.

However, attempts involving a larger model with a 20-foot wing span were unsuccessful. While Henson emigrated to the USA, Stringfellow, still financing himself by bobbin-making, continued his experiments. An unmanned demonstration flight of some 40 feet was achieved in August 1848 under a canopy specially erected for the purpose in Cremorne Gardens, London. In 1871 Stringfellow, now in his seventies, had built a steam powered triplane, which was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in London. The old man had planned to eventually build a flying machine which would carry him aloft, and equipped a building for just that purpose. Age and illness intervened, however, and that machine was never built. He died in 1883. All that was missing was that improved but elusive power source which he knew so well: electricity.

In 1843, to raise funds for their project, Henson and Stringfellow envisaged their Aerial Steam Carriage taking people as far as India, using an ingenious system for taking off (Chard Museum).

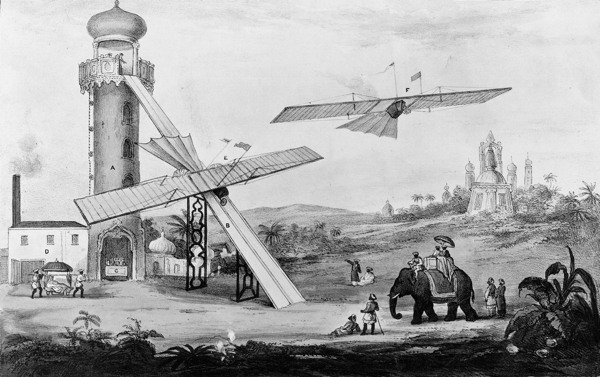

On New Year’s Day, 1871, Thomas Alva Edison, 24 years old, of Newark, New Jersey, who had already invented the electric vote recorder, the automatic repeater, and other improved telegraphic devices, speculated: “A Paines engine14 can be so constructed of steel & with hollow magnets. .. and combined with suitable air propelling apparatus wings … as to produce a flying machine of extreme lightness and tremendous power.”15

Nine years later, in 1880, a journalist working for the New York Daily Graphic obtained a scoop from the world-famous inventor of the phonograph and the electric light. In an interview given at Menlo Park, Edison is supposed to have confided to the journalist his latest project to build a featherweight “flying canoe,” borne aloft by two bat-like wings and operated by electric motors. Silk, stretched over a bamboo framework, would form the lifting surfaces, and the aerial boat would be steered from side to side by means of a bird-like tail at the rear of the cigar-shaped body. The craft would take two passengers and would be able to come down on land or water. Later on, the article recounts, Edison wanted to build a giant six-winged craft which could land on rough seas if necessary for flights across the ocean. Such a machine, driven by silent electric motors, would rush through the sky at one hundred miles an hour and would carry passengers from New York to Paris or Moscow nonstop in less than thirty hours. Weird skyscraper landing towers were included as a possible feature of such an airline. These huge pylons of steel, rising up above the lower clouds, would carry at their tops waiting depots and strange spoon-like landing cradles into which the big machines would settle at the end of a flight and from which they would take off again, loaded with fresh cargo and passengers. Lit with electric lamps and surrounded by a railed-in promenade, the octagonal waiting room at the top of the tower would provide shelter and refreshments for incoming and outgoing passengers. Electric elevators would make rapid trips up and down the tower.

Perhaps significantly, this interview as published on April 1, 1880, known to some as “April Fool’s Day,” or in French “Le Poisson d’avril” (April’s Fish), celebrated every year for its published hoaxes. Indeed, some months later, Edison stated that the Daily Graphic reporter had rather exaggerated the plans he had in mind. But the news was out and Europe was caught up with the idea that the Wizard of Menlo Park was constructing a flying machine to tour the world. In June 1880, Abel Hureau de Villeneuve of Paris, editor of L’Aéronaute: moniteur de la Société generale d’aérostation et d’automotion aériennes (The Aéronaute: Monitor of the General Society of Aeronautics and Air Automation) translated and reprinted the interview. De Villeneuve then pointed out that electricity simply would not have the power to make the Edison Air Ship work like bird flight.16

In reality, on 7 July 1880, Edison did make a rough sketch of a helicopter. He built a test stand and tested several different propellers using an electric motor. He deduced that in order to create a feasible helicopter, he needed a lightweight engine that could produce a large amount of power.17

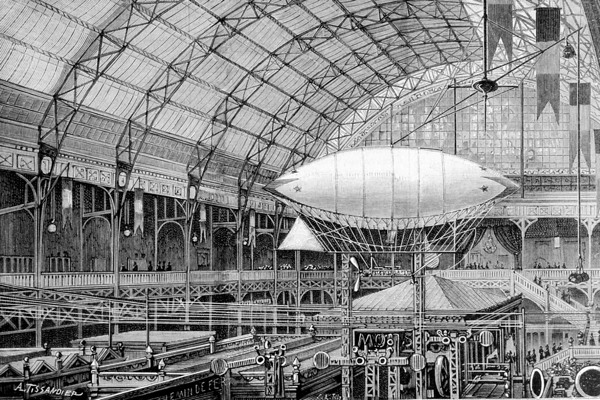

Ironically, it was the French who started more modest and realistic experiments with electric airplanes. In the fall of 1881, an International Electrical Exhibition was held in Paris, showing the applications of electricity to medicine, entertainment and transport. Floating under the roof of the exhibition gallery was the oblong aerostat of the Tissandier brothers, Gaston and Albert, experienced balloonists. It measured 3.5 meters (11 ft.) long, 1.30 meters diameter at the middle. It had a volume of 2 cubic meters (71 cubic feet) and 200 grams (7 oz.). Filled with pure hydrogen, it had a lifting force of 2 kg (4 lbs.). The lower part of the nacelle of the little balloon was equipped with a minuscule electric motor, built by Parisian electrical engineer Gustave Trouvé and weighing just 220 grams (7.7 oz.). What made the motor unique was that to make it lightweight, parts of it had been machined in the then-revolutionary aluminum.18

In 1880, inventor Thomas A. Edison is said to have disclosed in an interview with a journalist from the Daily Graphic that he had built an electric flying canoe capable of crossing the Atlantic, except that the hoax article was published in April 1, known as “April Fool’s Day” (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

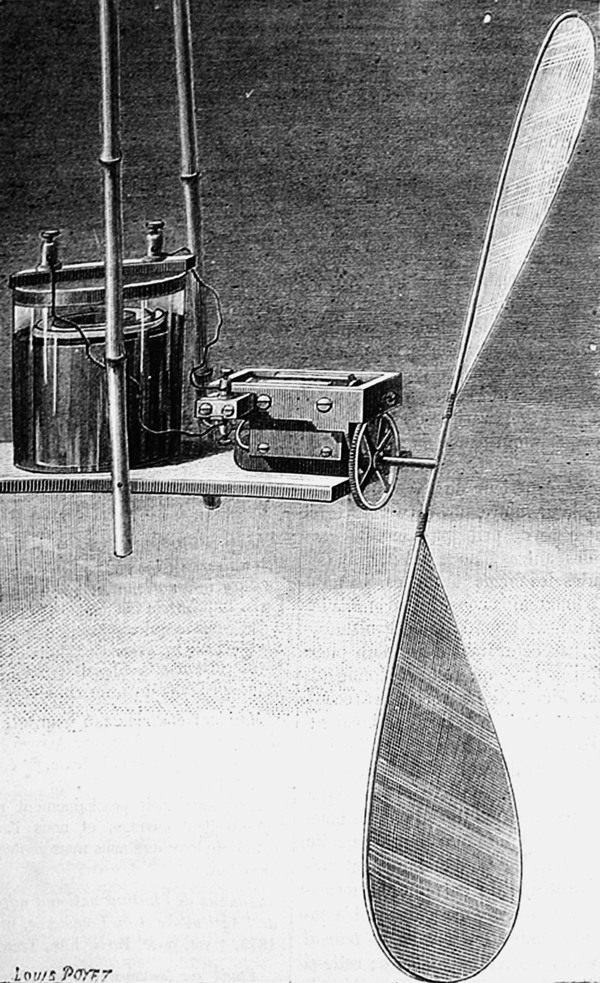

The shaft of this little machine was connected to a two-bladed propeller, made of wood and textile and turning at six and a half revolutions per second. Energy came from two small secondary lead-acid batteries supplied by the Tissandiers’ and Trouvé’s friend, Gaston Planté. The motor and the batteries had a weight inferior to the lifting force of the balloon and would be raised by this when it was filled with hydrogen.

Before arriving at the exhibition, the team had tested out their aerostat in the rooms of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, with the enthusiastic approval of its director, Hervé Mangon. Further experiments were then made in the workshops of M. Lachambre, in the rue de Vaugirard.

For the exhibition, in full view of the public, the little aerostat was tethered to a guide rope which towed it to and fro like a circus horse. It had a stern rudder to enable it to move right or left. Throughout the exhibition, demonstrations of the aerostat were given twice a week—on Thursdays at 4:30 p.m. and on Saturdays at 9 p.m. Visitors were entranced. Tissandier now calculated that with Trouvé’s motor, a scaled-up aerostat, in calm weather, could reach between 20 and 25 km/h (12 and 15 mph)!

During the International Electrical Exhibition, held in Paris in 1881, this electrically propelled tethered aéronef gave regular demonstrations to visitors, some of whom went away determined to build the full-scale version, while others were inspired to write fictional adventure stories (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

Among those hundreds who had admired the tethered aerostat was William Delisle Hay, an English writer and member of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1881, Hay’s science fiction novel Three Hundred Years Hence, or, a Voice from Posterity was published by Newman of London. In this book, set in the year 3001, Hay describes numerous types of flying machines; there are balloons whose canopies contain the extremely light “lucegen” gas; that canopy is positioned below rather than above the car. “The car was thus immersed, as it were, in a bladder covering it externally but leaving it open above; it sat in its balloon just as it might in water.” Even the author concedes that such a design might tend to lead to instability and turning turtle. To prevent this, he uses a powerful magnet which is attracted to the Earth’s magnetic field. Thus stabilized, the “Lucengenostat” is able to carry considerable weight of freight and passengers.

Yet these are superseded by even more powerful aerial machines, working on new principles. The lift is provided by “basilica-magnetism” for greater power and greater safety. The locomotive power may come from “generated heat and electricity,” which causes a pair of fans modeled on birds’ wings extending along the sides of the craft from stem to stern to flap. This type is known as the “alamotor” and is used for small utilitarian craft. Then there is the “spiralmotor,” driven by one or more propellers of the “pusher” variety normally placed at the stern. “Heat and electricity give the motive power, and this form is the most generally employed on aircraft.” For really heavy loads, the “zodiamotor” is available, being powered by the naturally occurring “zodiacal electricity.” When Hay says that “it is that which holds together the elements of air,” he can be construed (just) as referring to atomic energy. At any rate, his various flying machines are able to lift any weight and to travel at a thousand miles an hour, “though seldom employing more than half that rate.”19

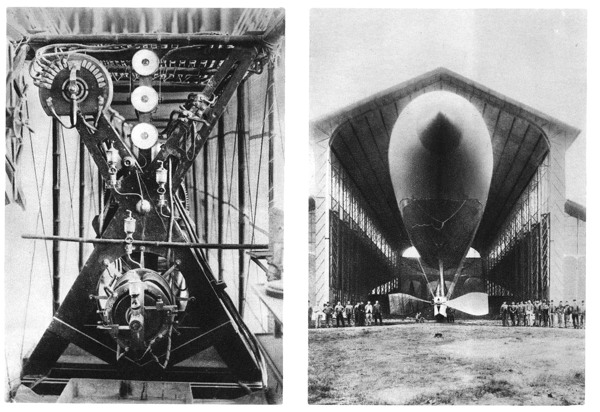

The 220-g (7.7-oz.) motor of the aeronef, using aluminum parts to make it lighter, was designed and built by Gustave Trouvé, electrical engineer of Paris, who would also innovate the electric tricycle and electric boat using the same engine design powered by rechargeable lead-acid batteries (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

While the English public marveled at Hay’s almost visionary imagination, back in Paris, Gaston Tissandier had taken out his seminal patent “New Application of Electricity to Aerial Navigation”: “Electric motors offer the following advantages: 1st their weight is constant, so that the balloon can stay balanced in the air … 2nd absence of fire, which offers a considerable danger under an aerostat inflated with hydrogen gas … 3rd the electric motor offers the advantage of the ease of starting and stopping, and that of the mechanical simplicity.”

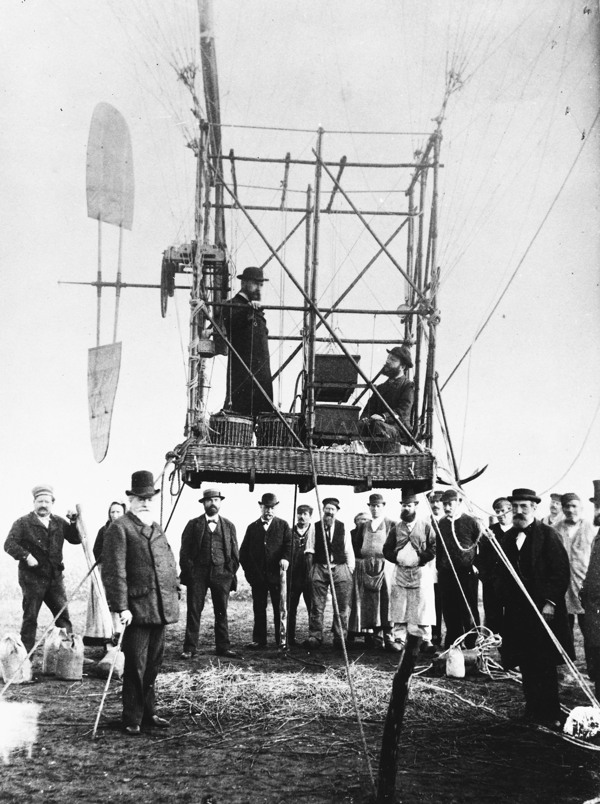

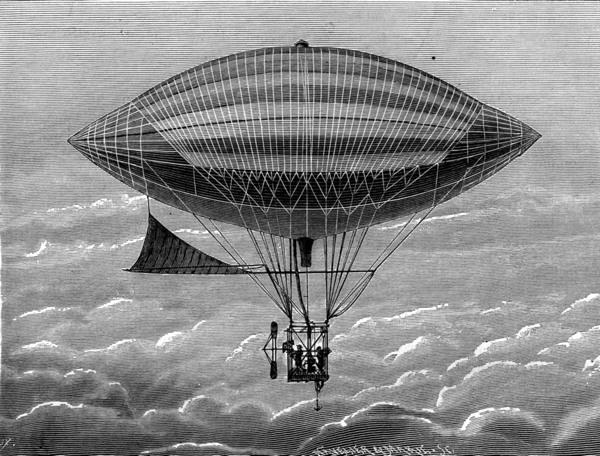

Tissandier also formed a company with the intention of scaling up his aerostat to man-carrying dimensions. During the two years that followed, the Tissandier team assembled the full-scale 28-meter (92-foot) version of the tethered Trouvé-engined aerostat they had demonstrated at the Electrical Exposition. Their nacelle was a cage made of bamboo lashed together with ropes and copper wire covered in guttapercha (rubber), while the floor was made of walnut planks surrounded by basketwork. It was equipped with a D4 long-coil motor specially built in their workshops by Siemens Frères and weighing just 54 kg (119 lb.). It was mounted on a wooden chassis with special transmission. Energy came from heavy-duty dichromate of potash batteries. The two-bladed canvas and bamboo pusher propeller turned at 180 rpm and could be warped by pulling on steel wires. The rudder was made of unvarnished silk also stretched over a bamboo framework. The envelope weighed 170 kg (374 lbs.), the motor and batteries 208 kg (460 lbs.), and with crew, the whole weighed 1,240 kg (2,734 lbs.).

On October 8, 1883, at Auteuil, southwest Paris, the airship rose up into the sky with the intrepid brothers on board.20 [W]hen we got our motor to function at great speed, with the help of the 24 elements, the effect produced was completely different. The movement of the aérostat was becoming suddenly appreciable, and we felt the cold wind produced by our horizontal movement. Our aérostat regularly planed at a height of 4–500 meters. When she turned into the wind, with her forward point headed for the Auteuil bell tower near to our departure point, she held her head to the oncoming wind and stayed motionless.…”21 This was the first time a real electric airship had taken to the skies! Thousands of Parisians looked upwards and gasped in awe and wonder.

The airship flew at a gentle speed of 10 kph (6 mph.), passing over the Bois de Boulogne. It held its head against the wind but the rudder had little effect, and after 20 minutes airborne, at 4:55 p.m., the Tissandiers had to land in a large field near Croissy-sur-Seine. Painters and photographers arrived to portray the aerial ship, among a big and friendly crowd that the novelty of the spectacle had attracted from everywhere. They left her inflated the whole night. They would have made a second ascent, but the cold of the night had crystallized the dichromate of potassium in the ebonite reservoirs, and the battery, far from being exhausted, was unable to function. So the Tissandiers took their aerostat back to the banks of the Seine close to Croissy Bridge and deflated it.

October 8, 1883, Auteuil, southwest Paris: the Tissandier brothers ready for takeoff in their Siemens-engined 28-meter (92-foot) airship (©D.R./Coll. musée de l’Air et de l’Espace, Le Bourget).

The Tissandier airship in the skies over Paris. Lack of rudder control forced it to land after a flight of only twenty minutes (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

They continued to improve their electric airship or aerostat. On the afternoon of Friday, September 26, 1884, to the clapping and cheering of a large surrounding crowd, it rose vertically into the skies again, with the brothers and a retired sailing captain called Lecomte on board. With its improved rudder, it flew for two hours, passing over Grenelle, the Luxembourg Observatory, Bercy Bridge, the Vincennes woods, Varenne-Saint-Maur, and Sucy-en-Brie. But without being able to go against a strong headwind, it had to land at 6:20 p.m. at Marolles-en-Brie, near Servon woods in the Seine-et-Oise region. In a letter sent three days later to Madame Hervé Mangon, Tissandier writes:

Albert and I were really tired on the day of our ascent. Nobody can imagine how much it costs to make such experiments, trouble and frustration. It required all our efforts on the previous night in our workshop to be ready to prepare everything for 5 o’clock in the morning. The workers who were with us turned pale from our demands; they fought and we had to separate them! I had to work almost alone with big gas appliance; I was covered with acid stains and splashes. On the descent, I got a few liters of dichromate of potassium acid we were carrying on my legs, and when I returned in the evening to Paris, I had the appearance of a convict. Albert remained the following day in Marolles where we had touched down, to bring back all the equipment.

“La Scala,” 13 boulevard de Strasbourg, Paris 10ème, named after Milan’s opera house, was famous for its operettas and popular songs. With the Tissandiers’ flight the talk of the town, it was rather fun that one of the songs was “Le Ballondirigeable” (steerable balloon), with words by Messieurs Lafaurié and Bourges and music by Monsieur Giraud-Malteau. The illustration on the front of the score was inspired by the Tissandiers’ aerostat.

Some weeks before, on August 9, 1884, a second cigar-shaped balloon had graced the skies, to the delight of the Parisians. Its battery was what is now called a flow battery—electrical energy was stored by pumping chlorine from one chamber to another containing zinc, and so generating power to a motor. Its creator was one Charles Renard. Louis-Marie-Joseph-Charles Clément Charles Renard was born in Damblain in the Vosges regions of France in November 1847. A clever child, he won a scholarship that eventually led him to graduate with honors from one of the leading polytechnics (France’s so-called “grandes écoles” or top universities).22

Renard was only 23 when the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870. Given command of a section of the 15th Army Corps on the Loire, he took part in the battles of Artenay, Cercottes and Orléans, and was awarded the Cross of the Légion d’honneur for his bravery in leading a defense against the Prussians. Extraordinarily, at the same time, this brilliant young engineer presented a way to adjust numerical values used in the metrical system for mechanical construction. The interval from one to 10 was divided into five, 10, 20 and 40.23 Incidentally, the Renard series, in one of the most obscure facts about ballooning, helped the French army to reduce the number of different balloon ropes kept in its inventory from 425 to 17!

Three years later, Renard, promoted to lieutenant in the 3rd Regiment of Engineers, started working on flying machines, with what he called a “directional parachute” or aéride. The idea was for a 10-winged glider, without pilot and weighing just 7.5 kg (16 lb.), to be launched from a balloon to transport messages. It was tested with success in 1873 close to Arras, from one of the towers of the Mont Saint-Eloi Abbey.

In 1877, Renard, assisted by Captain la Haye, founded the Central Establishment of Military Aérostation in the park of the old Château de Chalais at Meudon outside Paris. First, he modernized the existing equipment. This included the building of a powerful, continuous-circulation hydrogen generator, designed by Charles Renard and built under the supervision of his brother Paul.

Charles Renard, who led the project to build La France, the world’s second airship (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

They were next joined by Arthur Constantin Krebs. Three years younger than Renard, his senior officer, Krebs had also fought against Prussia. Transferred to the workshops of the Chalais-Meudon Aérostation, the innovative Krebs worked for Renard and la Haye, resulting in a direct circulation steam generator, called the Renhaye.

One of Krebs’s contributions was the development of the engine that would power the airship and the building of an electric boat, the Ampère, to measure the resistance of airship models. At the end of 1881 Renard had begun to research the electric generator indispensable for his project. His previous experiments showed he needed to create a generator capable of giving 10 hp for two hours, and weighing less than 480 kg (1060 lb.).

Working on the new theory of chemical affinity, Renard retained as his anodic couples chlorine and bromine. For the cathode: magnesium, aluminum, calcium and zinc. After he abandoned bromine for safety reasons, and magnesium, aluminum and calcium as being too expensive, the chlorine-zinc couple remained. The positive electrode retained was a silver-plated leaf of a thickness of one-tenth of a millimeter, the negative being a rod of pure zinc. After a great deal of experimentation he chose as his electrolyte a mix of hydrochloric acid at 11° Baumé and chromic anhydride, likely to release the chlorine. To avoid excessive overheating during the discharge, a tubular form was created, the container serving as a thermal radiator.

At the start of 1883, the construction of the definitive battery began. It had a specific capacity of 44 kg (97 lb.) per horsepower. Krebs built the electric motor: a rotor of two crowns of eight electromagnets, supplied on average by eight brushes. The whole weighed 88 kg (194 lb.) for 8.5 hp. On the side of the airship gondola, a steering wheel controlled the power of the batteries by pushing the zinc cathodes in and out of the batteries.

On August 9, 1884, the balloon airship La France took to the air at Meudon. It then flew above a farm at Villacoublay, then made a controlled return to Meudon—the world’s first closed-circuit flight. The flight lasted 23 minutes for a circuit of 8 km (5 mi), giving “le dirigéable” (steerable) La France an impressive speed of 19.8 kph (12 mph). On its seven flights in 1884 and 1885, La France returned five times to its starting point.

In 1884 and 1885, in making several controlled flights, La France, seen here at the Chalais-Meudon Aérostation, earned the title of “dirigible” (steerable). Its 88 kg 8.5 hp motor was a rotor made up of two crowns of eight electromagnets, supplied on average by eight brushes. Energy came from a revolutionary chlorine-zinc flow battery (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

The following year, Renard, now a colonel, persuaded France’s Minister of Finance to invest the then-staggering sum of 200,000 francs in the project, including the erection of a hangar necessary for the construction and sheltering of balloons and airships. This would become the cradle and home for La France, which had demonstrated that controlled flight was possible if the airship had a sufficiently powerful lightweight motor. In 1889 it was proudly put on show at the military pavilion in the Place des Invalides, Paris, during the Universal Exhibition held that year. Among those impressed by the technology was the Marquis Henri de Graffigny, who by coupling the Renard flow battery to an 8 kg Trouvé motor, was able to increase the range of his pioneer electric-pedal tricycle to five consecutive hours and a distance of 95 km.

But Renard also realized that lighter-than-air, battery-powered, electric-engined dirigibles had their limitations. And for the last 20 years of his life he would move away from electrical research and spend his time creating more efficient gasoline engines. In 1902, working with the engineer Léon Levavasseur, he developed a revolutionary V8 aero-engine capable of 80 hp.

But Renard’s last years were not happy ones. He had financial difficulties and grew tired of fighting the inertia within an army whose enthusiasm for aeronautics was lackluster. He was also a bachelor and his only relaxation was to visit his brother Paul’s family and play and compose on the piano. Then his health deteriorated. Early in 1905 he suffered a bout of flu, which lowered his resistance. On April 13 he was found dead in the office of his chalet in the park. He was 58. Although the official diagnosis was a heart attack, rumors circulated—and still persist to this day—that while depressed, Renard had committed suicide. The rumors were never substantiated.

Among those impressed by the 1884 flight of La France was Augustin Henri Hamon of Boulogne-sur-Seine. In 1885, Hamon wrote a book, Aerial Navigation, published in Paris by Marpon and Flammarion. The following year, he was awarded patents in France (350,303), Germany and England for a dirigible aerostat that incorporated an electric motor with battery, and in particular a propeller-wheel with feathering blades whose blade angle could be altered for ascent and descent. Although never built, Hamon’s ingenious design would later be seen again in ailerons and variable pitch propellers.

In March 1886, another aeronautical engineer called de Latour announced details of his battery-electric dirigible balloon. It would be propelled by a propeller turning at 300 rpm, giving it a speed of 4 meters (13 ft.) per second. Steering would be carried out using sails that could be furled and unfurled using a magnet, a prototype of the electric winch.24 Three months later, Abel Clarin de la Rive of Chalon-sur-Saône, a senior journalist for various French newspapers, published a pamphlet in which he reviewed: “All the attempts which have been made to control balloons … up to Captains Krebs and Renard. Having noted the inherent faults in each system, the author announces a new dirigible aerostat of his invention also equipped with an electric motor.”25

Another engineer was Constantin Senlecq, a notary from Ardres, northern France, and founding member of the International Electricity Company of Paris. Senlecq wrote a 12-page brochure, also titled “Aerial Navigation,” in which he proposed a system combining the advantages of lighter-than-air (balloon using hydrogen gas for the ascent) and heavier-than-air (char of the nacelle with a horizontally rotating propeller driven by a motor powered by electricity). Dated January 1886, this pamphlet was registered at the Academy of Sciences meeting of August 27, 1886. Senlecq’s machine was never built, nor was his “telectroscope,” the forerunner of television.

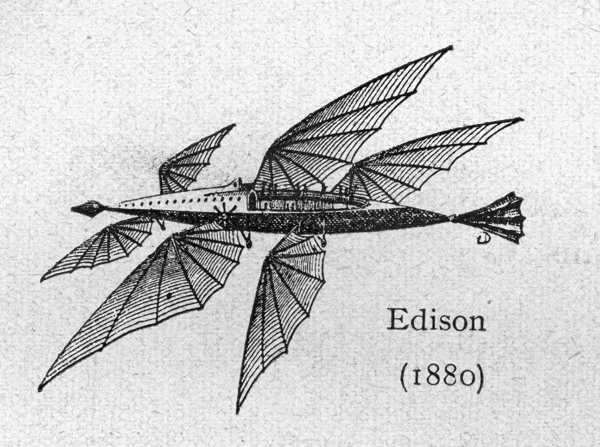

In the late summer of 1886, France’s popular science fiction writer Jules Verne serialized his novel Robur the Conqueror (French: Robur-le-Conquérant), also known as The Clipper of the Clouds.26 Robur’s Albatross is a slender, clipper-shaped hull made of hydraulically compressed paper or cellulose, 100 feet (30 m) long and 12 feet (3m 60) wide. Above its flat deck stands a veritable forest of slender masts, 37 of them, each with twin contra-rotating propellers at the top. At the bow and stern are two more propellers. A large rudder steers the “clipper of the clouds,” and spring-loaded shock absorbers cushion its landings.

As for its propulsion:

He employed electricity, that agent which one day will be the soul of the industrial world. But he required no electro-motor to produce it. All he trusted to was piles and accumulators. What were the elements of these piles, and what were the acids he used, Robur only knew. And the construction of the accumulators was kept equally secret. Of what were their positive and negative plates? None can say. The engineer took good care—and not unreasonably—to keep his secret unpatented. One thing was unmistakable, and that was that the piles were of extraordinary strength; and the accumulators left those of Faure-Sellon-Volckmar very far behind in yielding currents whose amperes ran into figures up to then unknown. Thus there was obtained a power to drive the screws and communicate a suspending and propelling force in excess of all his requirements under any circumstances.27

Often inspired by Verne, the Cuban-born Brooklyn writer Luis Senerans, alias “Noname,” devoted one adventure in the weekly U.S. dime-novel series to Frank Reade Jr. and his Queen Clipper of the Clouds: A Thrilling Story of a Wonderful Voyage in the Air. Again propulsion was by electricity. This was serialized between February and July 1889. Another story, The Electric Island; Or, Frank Reade, Jr.’s Search for the Greatest Wonder on Earth with His Air-Ship, the “Flight,” is a complete novel. The Electric Island itself, southeast of Kerguelen, is a gigantic storage battery, and to land on it, one must wear rubber boots and insulated clothing. The flora and fauna are electrified. The explorers must land with a land-dwelling eel and an electric tortoise. Natural spark gaps provide illumination. When a storm arises, the atmospheric electricity reacts with that of the island; things are too perilous for the men and they leave. The island sinks beneath the sea, for it was ultimately volcanic. The rotascope-lifted airship cracks up in Australia.

In his novel A Fortnight in Heaven: An Unconventional Romance, published by Henry Holt and Company, New York (1886), Harold Brydges (aka James Howard Bridge) describes the voyage to Jupiter of an English sea captain’s “spiritual double.” Here he finds gigantic humans populating an alternative futuristic America. One of the first spectacles to confront him is a new Chicago, transformed into a city of crystal. The main force behind this transformation is electricity, powering “electric pedestrianism” (through a kind of accelerated bicycle) and “aerial ships.”28

From 1886, perhaps inspired by the pioneering attempts of his compatriots, Dr. Arthur DeBausset, of French origins, resident of Chicago, ambitiously attempted to raise funds to construct his “vacuum-tube” airship design, which he called the “aero-plane.” Instead of being filled with lighter-than-air gas such as hydrogen or helium like a dirigible, DeBausset’s “aero-plane” gained buoyancy by having air removed from the cylinder by a vacuum system. The absence of air would make it float, with the huge size of the airless chamber negating the weight of a passenger cabin and the weight of the tank itself. Its riveted steel cylinder would measure 236 meters (774 ft.) long, with a cylinder diameter 44 meters (144 ft.). Its conical ends would be constructed of 1⁄44" steel plates. Power would come from six 60 hp engines; six 45 kW dynamos; 24 electric motors; 40 propellers; and 4 quadruple pneumatic pumps. It would have a top speed of 120 mph (200 kph) and a cruising speed of 100 mph (160 kph). This would promise, for example, two-hour trips between Chicago and New York, and overnight trips to Europe.

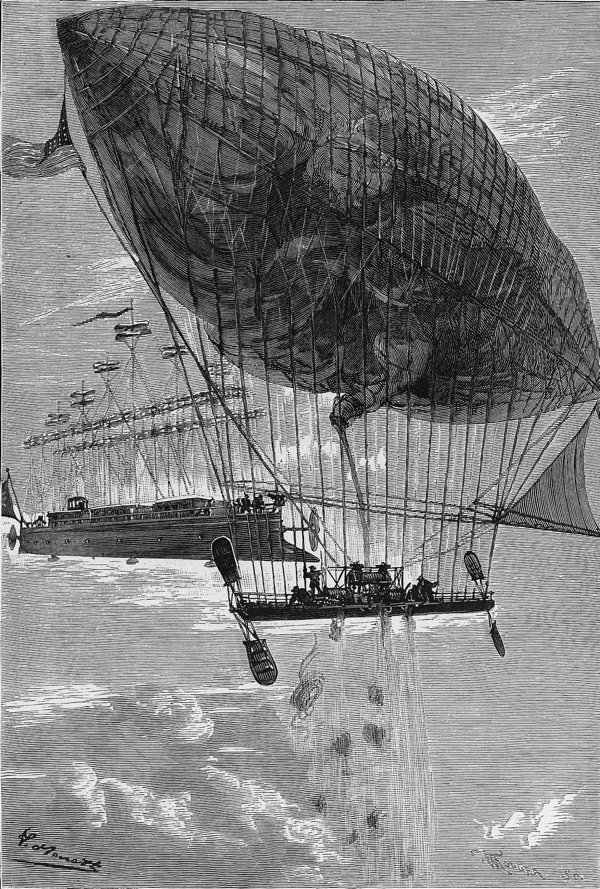

Among those inspired by such flights was the author Jules Verne. In 1886 Verne wrote Robur the Conqueror (French: Robur-le-Conquérant), also known as The Clipper of the Clouds. The 37 masts making up the distributed electric propulsion of the Albatross used accumulators to voyage through the skies (Bibliothèque Louis Aragon, Amiens: Agence Roger Viollet).

DeBausset’s pamphlet Aerial Navigation (a popular title for such books), printed by Fergus, was published under the auspices of the Transcontinental Aerial Navigation Company of Chicago, duly incorporated under the laws of the State of Illinois, February 18, 1886. In this Dr. DeBausset stated that the first notice of his invention was given at Saint Louis, Missouri, April 8, 1884, at a public conference he gave at Bomberger’s Hall, and reported by the Globe Democrat. On November 6, 1886, an article titled “A New Air-Ship to be Propelled by Electricity” appeared in The Electrical World, New York.

An article, “Mammoth Airships,” published in the Chicago Herald on March 20, 1887, begins:

Above the entrance to the hallway at 236 State Street is a gilt sign reading “Transcontinental Aerial Navigation Company.” In a pleasant office upstairs, its door bearing the same words, is found a short, round-headed Frenchman who answers to the name of Dr. A. DeBausset, president of the Aerial. He is a keen-eyed, energetic little man, who puffs at innumerable cigarettes placed one after another in a long amber holder, the while talking most rapidly in a language which is imperfect English with a full French pronunciation. Dr. DeBausset is the inventor of the aero-plane….

Writing in the “Chronique” column of XIXème Siècle, Journal Républicain, published in Paris, Raoul Lucet reported: “DeBausset’s ship can carry 200 passengers and is destined to explore the Polar regions. It will leave New York on June 10, 1888 (the departure time is not given) and head for the Pole, stopping successively at Philadelphia, Washington, Toledo, Chicago, Omaha, San Francisco, Jeddo, Canton, Constantinople, Rome, Paris, Berlin, Copenhagen, Stockholm and St Petersburg.”

In 1888, DeBausset published another pamphlet, titled The Arctic Explorer, in which he claimed that tickets for the maiden voyage of the AS Artemis had already sold out and the ship was still being fitted for passengers, while the demand had seen tickets changing hands for handsome sums. He even suggested that a four-strong fleet of “aero-planes” could take passengers across the Atlantic to the forthcoming Paris Universal Exhibition in thirty hours. At the time, a Cunard Line steamship held the record for a transatlantic crossing of 7 days, or 168 hours.

Promotional materials included testimonials by physicists backing the feasibility of the concept. DeBausset attempted to sell $100,000 in shares at $100 each to finance his venture, the U.S. government expressed interest for defense purposes, and a huge tract of land was secured in outlying Worth to build it. But the general public was skeptical. His patent application was eventually denied on the basis that it was “wholly theoretical, everything being based upon calculation and nothing upon trial or demonstration.”29

Not only was AS Artemis never even built, but DeBausset disappeared from Chicago, briefly resurfaced in New York City, then disappeared for good from the aviation and business world.30

At the same time, in February 1887, Dr. Martin Braun, of German origins, residing in Cape Vincent, New York, obtained Patent U.S. 356743A for an “Electro-Dynamic Air Ship.” Articles appeared in both Scientific American and Manufacturer and Builder. However, in his patent, Braun states, “Motion may be imparted to the shaft 24 by any suitable motor,” not specifically electric. There is no reference that the Braun craft was ever built or flown.31

Rather like the Tissandier brothers, Professor Peter Carmont Campbell of Rhinebeck, Duchess County, New York, was no stranger to balloons. Following his first ascension in 1857 in the Brooklyn Eagle inside the Crystal Palace, New York City, Campbell went on to patent five different air ships. In 1887, with advice and encouragement from Samuel Morse and Horace Greeley, Campbell submitted his latest, more controllable design to aeronautic engineer Carl Edgar Myers for examination. The craft comprised an oblong cylindrical envelope 60 feet (18.3 m) in length and 42 feet (12.8 m) across, filled with coal gas. A long metal rod beneath the gasbag served as a keel. The keel was directly tied to the bag at the center. A web of cords extended from the bar to the ends of the bag. A boat-like car was slung from the keel. Large enough to house a pilot and three passengers, the car sported two large birdlike wings on each side. The wings were not designed to be flapped, but could be raised or lowered to control the direction of motion. A forward rudder was also employed. A large, multi-bladed propeller was located on the underside and at the front of the car. Campbell had originally planned to use an electric motor and batteries, but considering them too heavy, he resorted to pedal power. He received the patent for this invention in May 1887 (U.S. No. 362.602) and the Dirigicycle was built by the Novelty Air Ship Company in the months which followed for $ 2,500.

On its first flight in December 1888, with James K. Allan at the pedals, the Dirigicycle rose 30 m; then, called down by Campbell for a photo, it easily descended. On the next flight it climbed to a height of about 150 m (500 ft.) and took half an hour to cross the sky between Coney Island and Brooklyn. On July 16, 1889, Professor W.M. Hogan’s brother Edward set out on a third flight from Brooklyn, New York. One of the propellers fell off, and the Dirigicycle was finally blown out to sea and lost. It was last seen 150 miles (250 km) out to sea heading for Africa. Edward Hogan was never seen again. It was later theorized that Hogan had been asphyxiated by coal gas escaping from the balloon.

Sometimes it paid to be less ambitious. Perhaps the first use of a flying machine to electrically transmit messages appeared at this time. A 30-year-old British meteorologist, Eric Henry Stuart Bruce, MA Oxon, conceived of a remarkably simple way to send message on a clear night in Morse code using a tethered balloon. Inside the balloon, made of transparent cambric, a little ladder was headed with six incandescent light bulbs, which were connected to a battery on the ground by a wire that ran side by side with the cable tethering the balloon. By switching the lights on and off through the translucent balloon, using the dot and dash system, the operator could telegraph messages to distant points, the only requisite being that the night must be dark and clear enough. By 1885, Bruce’s electrical war balloon had been adopted by the British, Belgian and Italian governments.

In 1888, Bruce was giving demonstrations to members of the Royal Society, the Royal Institution, the Institute of Chemistry, the Birmingham and Midland Institute, and in both the Town Hall in Kensington, southwest London, where he lived, and the Crystal Palace. He even produced a sales catalogue, giving as an advantage the absence of danger in introducing the electric light inside a gas balloon; detailing how to put a red-hot poker inside a balloon without setting fire to the gas; instructing how to signal over hills and woods, as well as coast signaling, and describing successful experiments at Chatham, Aldershot and Antwerp. During the 68th Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held in Bristol in 1898, Bruce gave a talk on “The Use of Electric Balloon Signaling in Arctic and Antarctic Expeditions.” From 1899, Bruce was Honorary Secretary of the Royal Aeronautical Society. Bruce soon found out, however, that his electric balloon signaling had been made redundant by the Morse wireless telegraphy developed by the Italian physicist Guglielmo Marconi, a system that could be sent in any weather conditions and at any distance. This did not stop Bruce’s inventiveness, which also resulted in such ideas as meteorological kites, about which he published a paper in Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society in 1909.

Over in Paris, Gustave Trouvé, at his workshop in 14 rue Vivienne, had continued to invent compact electrical machines for medicine, theatrical effects and transport. Toulouse is a town some 680 km (423 miles) south of Paris, and it was here that the French Association for the Advancement of Sciences held its congress on September 26, 1887. Among those things demonstrated by Trouvé was his 90 gram (3 oz.) Lilliputian electric motor which, fitted with an aerial propeller and attached to one end of a scale, once electrified, lifted the scale arm up. Occupying less than a 3 cm. (13/16 inch) cube, the motor could rise to a height of 22 meters (72 feet) in one second and would enable future experimentation with electric helicopters and aeroplanes.32

In the summer of 1891, twenty years after his first attempt, Trouvé resumed his ambition to build and fly a mechanical bird. After a summer of trials, he wrote a document, Study of Heavier-than-air Aerial Navigation. Tethered Electric Military Helicopter. Aviator Generator-Motor-Propelling Unit. Examining which motor was best qualified for aerial navigation, combining great power with lightness, Trouvé eliminated pure electricity: “I am rejecting the electric engine for the moment, for this reason: that with its generator and propeller, it goes beyond the weight of 8Kg per horsepower that I have demanded of myself….”33

Science fiction continued. In 1890, Robert Cromie, a Belfast journalist and novelist, wrote A Plunge into Space. In the book, Henry Barnett discovers, after 20 years of experimenting, how to control the ethereal force, “which permeates all material things, all immaterial space” and that combines electricity and gravity. Barnett succeeds in his experiments, and a large black globular spaceship, 50 feet (15.24 m) in diameter, called the “Steel Globe,” is secretly built in an inaccessible region in Alaska for a flight to destination: Mars. The book was first published in 1890 by Frederick Warne & Co. of London and New York. It was prefaced by Jules Verne, to whom Cromie penned this dedication: “To Jules Verne, to whom I am indebted for many delightful and marvelous excursions—notably, a voyage from the earth to the moon, a trip twenty thousand leagues under the sea and a journey round the world in eighty days—and who, in return, has now courteously consented to accompany me to the planet Mars, at the rate of fifty thousand miles a minute. Robert Cromie, Belfast, February, 1891.” It became a best-seller.

Hiram Maxim’s first patent concerned with electricity was in 1878, and he joined the first electric lighting company ever formed in the United States. He became their chief engineer, and as their representative he went to Europe for the Paris Electrical Exposition in 1881, displaying his machine for regulating the pressure of an electrical system. For this he was awarded the Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur. One imagines that, like the other visitors to that exposition, Maxim must have looked upwards and admired the Tissandier tethered electric aerostat.

When, in the early 1890s, as a successful machine-gun inventor and wealthy industrialist, Maxim built his unsuccessful prototype helicopter, he powered it with two lightweight naphtha-fired 360 horsepower (270 kW) steam engines driving two 17 ft. 10 in. (5.5 m) diameter laminated pine propellers. But before starting design work, Maxim carried out a series of experiments on airfoil sections and propeller design.

In October 1891, Maxim wrote an article “Aerial Navigation, the Power Required,” that was published in The Century magazine.34 In this, he began with a critical look at recent French attempts to build powered balloons (Tissandier, Renard), judging them a clumsy form of flight. “Look at birds,” he says. “A bird weighs 600 times more than the air it displaces.” He shows that a goose in flight never exerts more than a tenth of a horsepower. “Heavier-than-air flight is surely the way to go. Yet birds combine lift and propulsion in the wing, and that’s too subtle for us to mimic.”

Knowing he would have to separate the wing from the propeller, Maxim built a central tower with a 32-foot (10 m) rotating arm to measure the effectiveness of propellers and wing surfaces. A steam engine drove the arm. At the end of the arm was a propeller with a streamlined engine pod and a short section of a wing. That test configuration circled the tower at speeds up to 60 mph (100 kph), while an electric motor inside the pod drove the propeller. The apparatus offered a means for measuring power input to both the propeller and the rotating arm.

Maxim’s instruments let him separate out lift, thrust, and drag. He found that, at 60 mph, the propeller might use 16 horsepower to lift the wing and another 35 horsepower to overcome drag and its own inefficiency. With such detailed preliminary researches, Maxim had done superb work on the power inventory of flight, but he had not solved the crucial problem of controlling a moving airplane.

Over in Austro-Hungary, since 1884, Georg Wellner, professor of mechanical engineering at the TechnischeHochschule in Brünn (today’s Brno), had developed what he called a navigable sail balloon. He took the example of a paddle wheel ship, then placed the paddlewheel horizontally to the wedge-shaped balloon, otherwise a two-seater sail wheel flying machine, with power from a Siemens-Halske electric motor. The French called this a hélicoptère. Obtaining patents in 1895, Wellner experimented with a small model at the Hochschule; these efforts proved successful and promising, so work began on a 50 ft. (15 m) wheel. But when, by 1895, Wellner’s full-scale flying machine was given its first test, it was only able to lift 350 kg (110 lbs.) with an expenditure of 12 hp; the weight of the engine was 90 kg (200 lbs.), and it lacked a force of 540 kg (1,190 lbs.) to raise itself. Wellner continued to work on his sail-wheel concept, but without conclusive results.

On the ground and afloat, practical electric transport had become popular. On May 1, 1893, President Grover Cleveland pushed a button to inaugurate the World’s Columbian Exposition. During the six and a half months of the exposition, a fleet of 55 electric launches, built by the Electric Launch & Navigation Company (ELCO), made 66,975 trips on the lagoon, carrying 1,026,346 passengers 200,925 miles (323,357 km) and earning $314,000 for the World’s Fair organizers. Their greatest test came on Chicago Day, when 622 trips of three miles were successfully made by fifty boats. In London, Walter Bersey of the London Electric Cab Co. Ltd. ran a fleet of fifteen taxicabs, while over in Paris, a similar service of hackney electric cabs, fitted with EPS batteries, had been inaugurated by the Compagnie Générale des Voitures, its fleet rising to no fewer than 100 cabs.

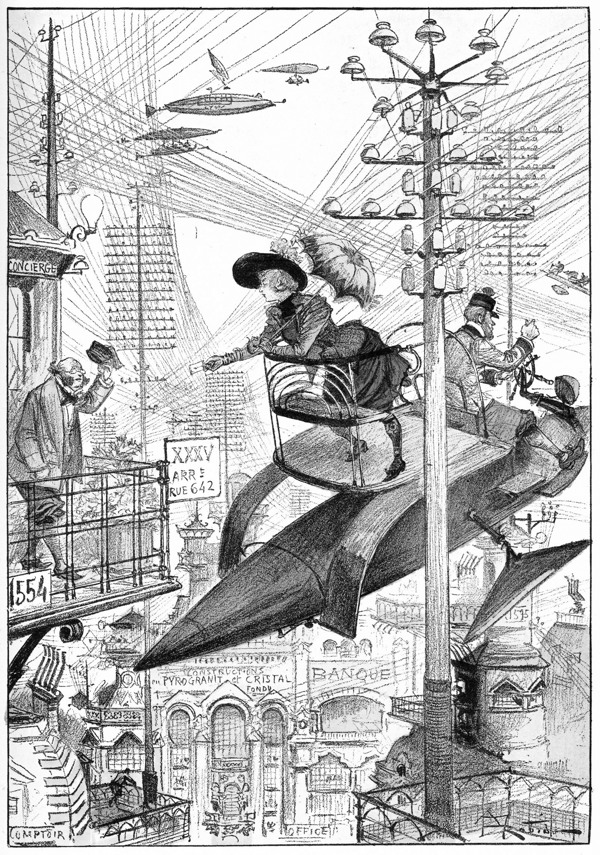

In this context, in 1893, French author Albert Robida wrote a science fiction novel, La Vie électrique (Vingtième siècle). (The Electric Life [The 20th Century]).35 In this, he looked at everyday life in the years 1952–1953, depicting machines made by an illustrious French scientist Philox Lorris, such as the “teléphonoscope” (an interactive television) and “les helicopters électriques,” vehicles that serve both for individual transportation and for military reconnaissance and attacks. These are put to the very widest use, day and night, moored to many rooftops. Public buildings like Notre Dame Cathedral served as balloon interchange stations.

The month of September 1952 was drawing to a close. Summer had been magnificent; the sun, cooler now, bathed the golden days of autumn with a soft and caressing glow. Airship omnibus B, whose route went from the central Tube station on boulevard Montmartre to the aristocratic suburbs of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, was following the winding lines of the outer avenues and cruising at the statutory altitude of 250 meters. The arrival of the train at the Brittany Tube had quickly filled a dozen airbuses parked above the station. A swarm of aircabs, veloces, skiffs, flashes, and baggage tartans (whose heavy-winged tugs can barely do 30 kilometers an hour) bustled to and fro.…

Robida’s fellow countryman, Camille Flammarion, a respected author and astronomer, and friend of Gustave Trouvé, wrote and published La Fin du Monde (The End of the World). In a story set in the 25th century, a comet made mostly of carbon monoxide (CO) could possibly collide with the Earth. The plot is concerned with the philosophy and political consequences of the end of the world. In his description of the Earth in five centuries’ time, Flammarion projects: “We traveled, especially during the day, preferably in airships, in electric aircraft, airplanes, helicopters, aerial devices, some heavier than air, like birds, others lighter, like aerostats.” In the Hungarian illustrated edition of this book, with a bevy of drawings done by famous French illustrators, one sees two lovers profiting from the intimate seclusion of their wing-flapping electric carriage!

The same year, George Chetwynd Griffith wrote and published his novel The Angel of the Revolution: A Tale of the Coming Terror (1893). The story begins on September 3, 1903, with twenty-six-year-old scientist Richard Arnold, devoted heart and soul to the invention of a flying machine, finally realizing his dream in the form of an airship that can fly on its own.

In his science fiction novel The End of the World (1893), Camille Flammarion envisions the skies filled with “electric aircraft, airplanes, helicopters, aerial devices, some heavier than air, like birds, others lighter, like aerostats,” even with room for romantic trysts! (Musée EDF Electropolis, Mulhouse).

Colston made his first inspection of the interior of the airship, under the guidance of her creator. What struck him most at first sight was the apparent inadequacy of the machinery to the attainment of the tremendous speed at which Arnold had promised they should travel. There were four somewhat insignificant-looking engines in all. Of these, one drove the stern propeller, one the side propellers, and two the fan-wheels on the masts. He learnt as soon as the voyage began that, by a very simple switch arrangement, the power of the whole four engines could be concentrated on the propellers; for, once in the air, the lifting wheels were dispensed with and lowered on deck, and the ship was entirely sustained by the pressure of the air under her planes.

Using this airship, a crippled, brilliant Russian Jew and his daughter, the “angel” Natasha, set up “The Brotherhood of Freedom” to establish a “pax aeronautica” over the Earth.36

Charles Dixon joined the genre with his Fifteen Hundred Miles an Hour, published in 1895 in London by Bliss, Sands and Foster. Professor Heinrich Hermann, FRS, FRAS, FRGS, has discovered that the space between planets is not airless but filled with a rarefied atmosphere that can be traversed by a ship with electric propellers, driven by a petroleum fuel cell of his own devising: “First, as to my means of conveyance. I have here a design for an air carriage, propelled by electricity, capable of being steered in any direction, and of attaining the stupendous speed of fifteen hundred miles per hour. It can be made large enough to afford all necessary accommodation for at least six persons, and its attendant apparatus is capable of administering to their every requirement.” Taking off in the Sirius, Hermann and some boys head off at fifteen hundred miles per hour to an adventure on the planet Mars!

The idea of supplying electrical power to a transport by cables was also in vogue. Only ten years after the first experimental trolleybus, in 1893, Frank W. Hawley, a wealthy entrepreneur and a director of the Cataract General Electric Company of Niagara Falls, converted a steamboat called Ceres into a trolley boat. Electricity was taken from the Rochester Street Railway station, and two 25 hp Westinghouse street railway–type motors using 500 volts were installed on board, each with its own shaft and prop. An initial line of trolleys was set up above New York’s Erie Canal, to which the boat was linked by two flexible wires attached to an overhead traveler. The first public demonstration of the renamed Frank W. Hawley trolley-boat was made on November 19, 1893, in the presence of New York Governor Roswell P. Flower and many distinguished guests, and was pronounced completely successful. The Financial Panic of 1893, political squabbling over the choice of electrical contractor, and the problems of positioning trolley wires for boats traveling through locks, over wide water stretches, or under raising and lowering drawbridges put a damper on an enterprising venture.