As a child, I had a book called The Wonder Book of the Air. I loved to look at the photos of the RAF’s latest jet fighter planes such as the Lightning and the Vampire, as built by English Electric Aviation Ltd. Ironic choice of company name? The company was formed in 1918 and made up of five businesses, including the United Electric Car Company of Preston and the Phoenix Dynamo Works. From World War II until the late 1950s, English Electric Ltd. built a sequence of bombers (the Hampden, the Halifax, the Lightning, the Canberra and the Vampire), but none of these were electrically propelled.

The real origins of electric aircraft as we know it today came from the aero-modelers of the late 1950s.

Control-line or tethered flying of electric model airplanes was not new. In 1958 Victor Stanzel of Schulenburg, Texas, filed a patent for a remotely-controlled propulsion and control mechanism for model aircraft. His patent U.S. 3,018,585: “The provision of electrically powered propulsion mechanism for model aircraft wherein the electric motor and power supply therefore is located at a distance from the craft so that the weight of such mechanism does not affect the craft in flight. A further object of the invention is the provision of an electrically powered model aircraft which is operated by an electric motor and power supply source located at a distance from the craft and drivingly connected thereto by means of a flexible shaft.”

But free flight with an electric model airplane was a challenge. The first to take this on was Englishman Harold John Taplin. “Taps” was born in Stoke Newington, London, in January 1891. By the outbreak of World War I, Taplin had become a professional aero engineer and designer by working for the Empress Motor Car and Aviation Co. in Manchester. In August 1916 he was appointed a probationary 2nd lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps. Embarked for France as an engineer officer in December 1916, Taplin returned to the Home Establishment to take his aviator’s certificate (No. 4483) in a Maurice Farman in April 1917. He ended the war with a staff appointment in the temporary rank of captain at the Air Ministry, though he is believed to have served as a test pilot and instructor in the interim, and was demobilized in January 1919. He returned to his pre-hostilities profession as a designer, and as he worked for Gerrand Industries Limited in London, a wide variety of his work was registered with the UK and U.S. Patent Offices in the 1920s and 1930s.

By 1957, Colonel Taplin was running Electronics Developments Ltd. when on June 30, his Radio Queen made the first official recorded electric-powered model aircraft flight above Chalgrove Aerodrome in Oxfordshire, England. He was assisted by his son Michael. Electrical power for the colonel’s model was supplied by 20 Venner H-105 silver/zinc cells weighing a total of a little over 28 oz. (800 g). Motor weight was 30 oz. (850 g) and the total model weight was 8 lbs. The government-surplus Emerson D20 motor pulled 8 amps. Total weight, 8 lbs. (3.6 kg) (and just like now, a 10-minute flight was optimum).1 Radio Queen managed an altitude of 10 m. The colonel died in 1969, but by then both Fred Militky of Germany and the Boucher brothers of the USA and Sanwa Denki Keiki Seisakusho of Japan were also experimenting.

Alfred Militky was born in 1922 in Jablonec nad Nisou, northern Bohemia. From his childhood, he devoted himself to making model aircraft. In this he was helped by a jeweler’s son, Heinrich Brditschka, who made their propellers. In the 1930s Militky read about Professor Alexander Lippisch’s Delta Wing aircraft gliders at the German Institute for Sailplane Flight, DFS. At the beginning of World War II, Militky of Gablonz, in his early twenties, was part of the Nazi Hitler Youth Movement, making and flying swept-wing duration-flight gliders, some of them powered by rubber bands flying for up to 20 minutes, others unsuccessfully attempting to use small gasoline and electric engines. Brief mentions of these are made in the magazine Deutsche Luftwacht Modellflug (German Sky Guard Aeromodeling). He joined the Luftwaffe as a pilot but the end of the war precluded any flying service. In January 1956 he and his wife Wilhelmine arrived in Kirchheim-unter-Tech to work for Johannes Graupner’s innovative model-making firm.2

That year, Militky produced the “Cobra” High-A2-performance glider, radio-controlled with a solenoid magnet control fitted in the nose of the fuselage. It won a gold medal, with a 28-minute flight soaring to 600 meters (2,000 ft.) above the Rhöne. Indeed, Militky took out a German patent for his “Steerable Bondage Airplane” Model Glider model (DE 1053992). This was the first of 300 models that the prolific Militky would design for Graupner during the next 20 years.

In February 1959, Dr. Ing. Fritz Faulhaber walked into the offices of the German magazine Modell and inquired if a motor which had an ironless rotor coil with self-supporting helical coil that his company, Schönaich near Stuttgart in Baden-Württemberg (Germany), had developed and patented for use in remote-controlled camera shutters, might be of use in modeling. The Faulhaber Type 030 was a coreless motor with integral gearbox. Militky immediately saw its advantages, and very soon after, the “Micromax” motor was powering Graupner aircraft. Its energy came from a battery made for use in electric cigarette lighters, the Rulag RL4, as developed by Artur Rudolf before the war. Encased in plastic and weighing just 1¾ ounces (50 g), the RL4 could not be recharged, but lasted long enough to get the glider into the sky.

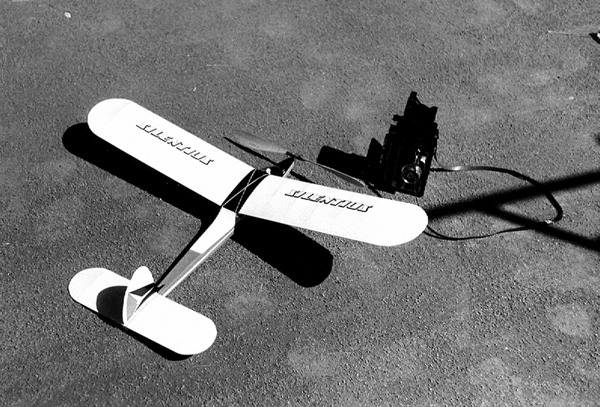

On March 18, 1959, after countless tests, Militky’s FM241 (his 241st model), otherwise known as “Der ElectroFlug,” glided out of sight after a five-minute climb. On October 4, 1959, FM 248 made a 23-minute flight. Because of the overload of the motor, the flight was limited in its duration. By September 1960, Militky had progressed to FM254, an improved kit version known as the F/F Graupner Silentius FM 254.3 This was the world’s first purchasable series electric plane.

Militky and Hilmar Bentert worked together to make it even more remote-controllable. They were ahead of their time: By 1988, Graupner’s Elektro-UHU motor glider was a world bestseller.

Militky was not the only one. In 1961, his compatriot Helmut Bruss built an electric model airplane with a twin pusher-puller propeller, powered a silver-zinc H-105 battery. On February 18, he created a remote-controlled record.

Over in Japan, in 1941, Sanwa Denki Keiki Seisakusho of Higashiōsaka, in the Osaka Prefecture, had established a company manufacturing and selling diagnostic tools, or multi-testers (circuit testers), for use in equipment repair. In 1962, his company marketed the Electra electric model aircraft, its fuselage made of expanded polystyrene.4

On October 4, 1959, Fred Militky of Graupner at Kirchheim-unter-Tech prepares his electric-powered Elektroflug FM 248 for its record 23-minute flight (Fred Militky collection Giezendanner).

What if the electric airplane could derive its power from the ground, without the need for batteries? In 1964, William C. Brown, an expert in microwave radar working for Raytheon, flew a unique model helicopter that received all of the power needed for flight from a microwave beam (2.45 GHz microwaves). This demonstration was seen by millions of viewers during Walter Cronkite’s CBS News program. The longest flight of this microwave helicopter lasted 10 hours. Brown’s microwave-to-DC converter was patented in March of 1969 (3434678).

In 1960, the Graupner Silentius FM 254 was the world’s first purchasable series electric plane. Photographed here next to a still camera (Fred Militky collection Giezendanner).

The big breakthrough came on September 4, 1971, when Fred Militky and Wolfgang Schwarze flew their radio-controlled twin-engined electric glider model Silencer to a height of 150 meters (500 ft.) in front of an amazed audience at the Seventh F3A World Championships for 22 nations in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The following year Militky came up with his twin Jumbo 2000F-engined Hi-Fly with its 2.3 m (7.5 ft.) wingspan. The first electric flight competitions were held as early 1973, including the Militky Cup in Pfäffikon, Switzerland, a contest that it still held annually.

For Fred Militky, the next step seemed a full-scale airplane. About this time the first energy crisis hit the world. Militky met up with his old school friend from Jablonec nad Nisou, Heinrich Brditschka, now head of a sailplane-building company in Haid, Linz, Upper Austria. The Brditschka jewelry firm had been destroyed during the war. In the 1960s Heinrich Brditschka had teamed up with Franz Raab to design and build die Krähe (The Crow), a two-seater 36 hp gas-engined motor glider, the HB-21. In 1971, persuaded by Militky, the Brditschkas decided to take on the challenge of a full-scale gas-free electric aircraft. For the technology of this they could count on Heinrich Brditschka Jr., known as Heino, who had studied aeronautics in Vienna. Heino had been co-designer, engineer, and builder at his family’s firm of their HB-3 and HB-21 motor gliders, then powered by Steyer Puch 650 or ROTAX.i/c combustion engines. Heino’s son would later recall:

My father Heinrich’s childhood friend, Fred Militky, was a very calm, thoughtful guy, but he also had a sense of humor and was often joking. He was very precise in his work and was always ready to welcome the latest technology. He had no children. He and his wife Wilma would travel everywhere in one of the first BMW 2800 Coupés, in the boot of which he almost always had one or two remote-control model gliders which Wilma would carry around for him.

One day, Militky came to us with the interesting project: to equip one of our sailplanes with batteries and motor and make it fly. At first we thought he was really mad! But he insisted and before long we were meeting up with technicians from Bosch motors and Varta batteries. After careful study of their documentation, we saw a real possibility to install them in the second prototype of our HB-3 OE-9023, which I had already test flown for many hours and knew well. With a wingspan of 12 m [40 ft] and fuselage length of 7m [23 ft], a wing area of 14,22m2 [153 ft2] indicated that stretching came on 10.11. HB-3 380 kg resulted in a wing loading of 26.72 kg / m2, so the best glide ratio was about 20. The HB-3 was not therefore an optimum performance motor-glider.

We called our project MBE-1 (Militky / Brditschka / Electric-1). Our team was made up of me and my father, Fred Militky, my pilot friend Manfred Bleimschein and our mechanic Wolfgang Weigel.

We began by taking everything unnecessary out of the sailplane: gas engine, fuel tank, fire wall, various instruments, interior trim, etc. We designed and built an engine mount for the delivered Bosch unit and a battery frame. We then used a fuselage of the series HB-21 for ground tests of the provisionally installed batteries and motor. The brilliant Ernst Voss of Varta provided 100 volt batteries normally used as back-ups for conventional airplanes and helicopters. They consisted of 120 standard NiCad cells with sintered plates in four special containers of 30 cells each with a rated capacity of 25 Ah. and an overall weight about 125 kg [276 lbs.]. Bosch supplied a 10 kW Focus DC belt-driving the prop at 2400 rpm. This increased the weight of the MBE-1 to 440 kg [970 lbs.], an additional 60 kg [132 lbs.].

These run-ups with static thrust measurements, behavior of the batteries and the motor confirmed our decision to fly it. We overcame the problem of the large current circuit by using a streetcar emergency switch in the handle. The Austrian aviation authority had to agree to grant a license for the test flights. At first they thought this was a joke but after studying the documents we submitted to them, they issued a permit (0E-9023). Anyway everyone thought that we would not get beyond a few hovers in a few meters above the runway.

Came the day when MBE-1 was transported to Wels. The airfield there is relatively large and has a good infrastructure. During the week, there is very little air traffic and we almost had the aerodrome to ourselves. We estimated that flights of 12 minutes duration at up to an altitude of 380 m [1,247 ft] were just within our NiCad battery’s capacity.

After assembly of the aircraft and the necessary checks, it became serious. The cockpit had been simplified for weight reasons. There was an airspeed indicator and an on-off switch for the motor—just flat out or nothing. We had two sets of batteries. On my first trial I made some run-ups, rolling trials and acceleration runs. The acceleration felt much the same as with the gas engine. On the 1200m long track I could take off shortly. The second time I was able to rise to an altitude of 50m [160 ft]. After these tests, the batteries were measured and they still had sufficient capacity. The tests lasted approximately 5 minutes, but the Varta batteries still had about 5 minutes “left.” So we could make a flight of ten minutes.

Having replaced the batteries, everything was ready for the first flight. The date was 21 October 1973. There were only a few spectators. The manager of the aerodrome had agreed to act as official witness for the first flight. The weather was not particularly good but calm and no precipitation with sufficient visibility. My old flight instructor Hans Dorant would follow me in a Cessna 150, observing the whole thing from the air and measuring my altitude.

With fully charged batteries, I was towed by a car driven by my technicians Bleimschein and Weigel to start site and placed in position.

In the cockpit, I made my last checks, locked hood, belted, etc. I went over my flight plans once more in my mind: Take off and climb to about 50m [160 ft] to the runway center, then decide whether to follow a traffic lane or whether I have to pull back and then before the end of the runway still can come to a standstill. That I was about to make aviation history did not enter my mind.

The Cessna behind me had already taken up position, ready to follow me inconspicuously.

Next followed the GO signal from the team. Motor switch ON go—good acceleration to about 55 kph [35 mph]—the plane then allowed to stand well at about 60 kph [37 mph]. The climb up to about 50m [160 ft] proceeded relatively quickly and continued unabated. This was followed by a straight climb to about 150m [500 ft]. I was flying electrically, but the prop noise the same, there did not appear to be any difference from the gas combustion engine. I banked in the traffic pattern and made the downwind leg in a few circles, decelerating. Then I switched off the engine and made about 1 minute a glide, and then I turned it on again. It also came out a little climbing performance, but not for long. I flew into the base leg and final approach to landing. I made a smooth landing and stopped. My flight had flight lasted 9 minutes 5 seconds. I opened the hood, the team and the few spectators were already there, cheering and congratulating us. It had been a very special flight.

After cleaning up and talking shop a little, the day passed like any other. For our next experiment, we would invite the Press as we wanted to introduce our novel aircraft to a broader public. We contacted the local press, television, radio and the APA (Austrian Press Agency) and the international press.

What we had not considered was that 1973 was the year of the first major oil crisis / gasoline crisis. In many countries, vehicle traffic was restricted. In Austria, you had to stick a sign with a week into the windshield, where you could not go. So for the Press, an aircraft which could fly without fuel was of enormous interest. We gave some demonstrations of “the world’s first battery airplane” for over a hundred radio and television stations from around the world. In fact we made a further 8 test flights, one on October 23, the best lasting 14 minutes at an altitude of 360 meters [1,100 ft], with a climbing speed of 1.5 to 2m / s.—a performance unequalled for the next ten years.

Our MBE-1 team got white overalls and for a few days we were the center of attention, about which we were very proud. Wels Airport was completely occupied only by us and the press photographers and reporters. Those reports continued for weeks and even months. In 1974, we proudly exhibited our MBE-1 at the Hannover Air Show.

But, having demonstrated we could fly with electric power, we returned to our daily lives. We had stored the energy of about 1.5 l petrol in only 140kg [308 lbs.] of batteries. Now forty years later, the worldwide arrival of the regular electric airplane and its everyday acceptance is taking a little longer. I feel sad that my good friend, Manfred Bleimschein, who died young, did not live to see and fly the extended range of the gliders which we at Brditschka make today.5

In October 2017, the restored MBE-1 was unveiled as a static exhibit for permanent exhibition at the Austrian Aviation Museum in Graz.

In 1974 Militky took out a patent for the engine (DE 2414704 A1). Today Brditschka electric motor sailplanes can fly for 500 km.6 In November of that year VFW-Fokker (the Technical Aeronautical Bureau of Fokker) in Bremen applied for a patent (U.S. 3937424 A) for an electric airplane. The applicants were Hans Justus Meier, Herbert Sadowski, and Ulrich Stampa. During World War II, Stampa had worked with Kurt Waldemar Tank, chief designer of the Focke-Wulf fighters for the Luftwaffe. In their design, the interiors of central wing cases of an electric-powered airplane would serve as battery cells. Load-bearing transverse walls would take up bending stresses integrated into such walls by tops and bottoms of such a central wing case. These tops and bottoms would constitute the electrodes of the battery. Leading and trailing edge-profile completing wing cases would be release-secured to the transverse walls of the central wing case. The airplane would have two pusher propellers mounted on the wings. This patent was published in February 1976. While Ulrich Stampa came to be regarded as the design-father of the VFW-Fokker 614 jetliner with its engines mounted in pods on pylons above the wing, the electric airplane was never built.

MB-E1 was the world’s first full-scale electric airplane, equipped with a 10 kW Bosch Focus motor and Varta NiCad batteries. In October 1973, piloted by Heino Brditschka, MB-E1 made eight flights from Wels airport, the longest for 15 minutes at an altitude of 360 meters (1,100 ft.), with a climbing speed of 1.5 to 2m/s, a performance unequaled for the next ten years (Brditschka Collection).

Across the pond, the twin Boucher brothers, Bob and Roland, were also pioneering electric model aircraft. From a Quebecois family in Canada, they had become interested in airplanes in 1939, when their father took them on a plane ride in a Gull Wing SR-7 Stinson Reliant. At once, they were both hooked on aviation. They first started with simple rubber-powered models. After graduating from Yale with master’s degrees in engineering, the Boucher brothers both moved to Los Angeles to work as engineers for the Hughes Aircraft Company on military programs. Roland was a project manager in the space division and Bob was a department manager in the missile division. Bob bought 1/7 interest in a Cessna 180 taildragger and spent many weekends traveling around California or visiting Los Vegas. One summer Bob flew his Cessna on a round trip across the USA from Los Angeles to Windham, Connecticut, and back to Los Angeles.

Again, it wasn’t long before they began to design and manufacture high-performance

radio-controlled sailplanes for hobbyists to use in AMA radio-controlled slope racing

and soaring contests. To that end, in 1969 they founded their own company, Astro Flight,

in their two garages in Los Angeles. Their first sailplane design, the Malibu, finished third in its very first trial at a slope contest in San Jose in the summer

of that year. In order to promote the Astro Flight name and their line of radio-controlled

models, they decided to try to break the existing FAI closed-course world record for

RC sailplanes, at that time slightly over 100 km (60 mi). For this they would need

a steady wind against a slope for at least 6 hours. When Bob visited the local federal

weather bureau to find data on local wind conditions, he was told to call Paul MacCready,

who was said to know where all the winds blow.

This was the beginning of a long friendship with Paul. Paul suggested Sandberg Mountain in Southern California. We both got our Malibu sailplanes ready at dawn on the mountain. The wind was more like a gale of 40 mph (65 kph) and soon both our models were smashed. We needed slope with a steady trade wind. The next spring Bob’s wife Suzanne won a raffle with tickets to Hawaii for a two-week vacation. He knew about the trade winds there and took along his Malibu for a try at the world record. That August 30, 1970, with the help of the Kapiolani RC club Bob flew my Malibu to a new FAI world record of 302 km (188 mi) on the slopes of Waimanalo Beach, Hawaii.7

The Bouchers now turned their attention to electric flight. The Fournier RF-4 single-seater motor glider designed by René Fournier had become a popular subject for radio control modelers on both continents. Roland had designed a 1/6 scale model of the RF-4 powered by the then popular O.S. Max 0.15 cu. in. 2-stroke model engine. It was a popular Astro Flight kit. Roland converted the model to use a rewound 12-volt ferrite motor powered by eight GE sub-C nickel-cadmium batteries and a 15-minute fast charger. Roland demonstrated his Fournier RF-4 electric R/C airplane at a trade show in Anaheim, California, in April 1971, marking the debut of America’s first practical electric-powered model airplane.

Still, the demand for electric-powered models was not brisk. Perhaps another world record might help. Roland redesigned his RF-4 to accommodate a larger Astro 25 ferrite motor and a large off-the-shelf Eagle Picher silver-zinc battery. Roland flew it to three unofficial world records: distance, 19 miles (31 km); duration, 29.5 minutes; and average speed, 55 mph (89 kph). Since no official categories for electric flight existed at the time, neither the AMA nor the FAI recognized these records. But the flight was witnessed by U.S. Army Colonel H. Federin of DARPA.

After considerable negotiations, the Bouchers finally received their first military contract with the Northrop Corporation to develop a low-altitude electric surveillance drone. Bob and Roland both quit Hughes Aircraft Co. and the real Astro Flight Inc. was born. With Bob Boucher as project manager, aided by his brother Roland, their wives and their lone employee Dave Shadel, Astro Flight finished the design in only six months. The result was the Model 7212 flying wing. With a wingspan of 8 ft (2.4 m), the 7212 was powered by three of the company’s Astro 40 ferrite motors each turning a three-blade, 8×8 propeller. The 7212 set another unofficial record in August 1973 by carrying a 7.5 pound (3.4 kg) lead payload over a closed course for an hour and twenty minutes at speeds reaching 75 mph (121 kph). It provided a stable platform for optical surveillance systems with no thermal or audible signature. In fact, the 7212 was completely inaudible at altitudes over 300 feet.

In July 1973 the Bouchers applied for a patent on a “Remotely Controlled Electric Airplane” and were granted United States Patent 3,957,230. Bob Boucher has recalled:

DARPA showed little enthusiasm for either Astro Flight or our “crazy” idea for an electric powered air surveillance vehicle. John Foster was more reasonable and suggested that if we could figure out a way to increase our flight times to twelve or more hours we might have a sale. Our NiCad battery powered models could fly comfortably for fifteen minutes and with careful energy management for about thirty minutes. We experimented with one-shot lithium D cells built by Power Conversion of New York in a lightweight r/c model and demonstrated flights over three hours with no payload. But for twelve hour flights we needed a breakthrough.8

The DARPA contract was over by November 1973 and the model business could not pay the rent. In February 1974 Bob Boucher rented a booth at the Nuremberg Toy Fair in Germany. “There I met Militky at the Graupner booth. He was still pushing an under-powered electric sailplane. In contrast, we had determined that we would replace the internal combustion engines in RC models with electric motors. I brought two models with me, the Electro-fli and the Fournier RF-4. These could rise off ground (ROG) and perform level 1 aerobatics, loop, stall turn, etc. Simprop Electronic picked us as supplier so I came back with a $50,000 order. We were back in business.”

The American and European initiative was soon followed in other parts of the world. Australian airline pilot Jack Black, having assisted at the Militky Cup, held in Pfäffikon, Switzerland, returned to Sydney. There he began to build and fly model e-sailplanes he called Pfäffikon, which he demonstrated in the early 1980s at the Sailplane Expo in Armidale, New South Wales.

By this time the sun had risen for electric aircraft.