To understand how one-off prototypes can be transformed into commercially manufactured units, we should glance back at commercial aviation history. In February 1909 the three Short brothers obtained the British rights to build the American Wright Flyer. An initial order for six aircraft was taken, all of them taken up by members of the Royal Aero Club. Short Brothers thus became the first aircraft manufacturing company in the world. They built these biplanes at their workshop on unobstructed marshland at Leysdown, near Shellbeach on the Isle of Sheppey. During World War I, the Sopwith Aviation Company built more than 16,000 aircraft and employed 5,000 people. From 1913 to 1933 the Avro Company built over 8,000 AVRO 504 training aircraft at several factories. By the Armistice, the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company would claim to be the largest aircraft manufacturer in the world, employing 18,000 in Buffalo and 3,000 in Hammondsport, New York. Curtiss produced 10,000 aircraft during that war, and more than 100 in a single week.

Sixty years later, in 1967, came the Boeing 737; eventually 8,800 were built. The 747 first flew in 1969; 1,520 were built.

The threats to the climate, the demands of government, and above all the needs of business have pushed on the development of electric aviation. But would these pressures have the same commercializing effect as the needs of air war?

As in the past, individuals and small operations have often led the way, from the land first. In 1967, Wilt Paulson of Lektro, which had pioneered the electric golf cart, produced a small electric aircraft tug for an Oregon FBO using a chassis originally built for an electric cart for area mink ranchers. Wilt Paulson’s friend, Cy Young, owned an FBO called Flightcraft. Paulson and Young noted that towbars often caused damage to nose gear and were overall problematic. Young wondered if the nose gear could be lifted with a scoop to cradle the gear, eliminating the towbar. From this idea, Wilt Paulson produced a small electric aircraft tug by turning around the mink feeder chassis and attaching a hydraulic scoop and winch, and towbarless towing was born. By 2014 Lektro had manufactured some 4,500 electric towbarless tugs.

In July 2010, Axel Lange was honored with the prestigious Lindbergh Award, presented by Lindbergh’s grandson, Erik Lindbergh. Lange had extended his range of motor gliders to 18, 20 and 23 meter models. The 20- and 23-meter (60- and 75-ft) variants can be equipped with a 42-kW electric motor and SAFT VL 41M lithium-ion batteries. Lange Aviation is currently also the most experienced serial producer of certified electric drives with more than 90 aircraft delivered since 2004. These are more than all other electric aircraft globally combined. The fleet has almost 100,000 hours of flying experience. For many years, there has been an annual Antares meeting organized by owners, where up to twenty-five Antares participate.

On February 24, 2012, the first ground works for the new Pipistrel facility for the production of the new 4-seat aircraft Panthera started in Italy, 15 miles (25km) away from the current Pipistrel headquarters in Slovenia. The new facility was built at the Duca d’Aosta airfield next to the town of Gorizia. The value of the building, together with the administration and management extension, exterior and all the equipment, amounts to 5 million Euro. The building is completely energy self-sufficient, beginning with a 1.1 MW solar power plant—later increased to 1GW—on the roof of the complex, the same quantity of energy as a medium-sized city uses in one week. The combined worth of the investment was 7 million Euro. The first electric airplane in the production line is their Taurus Electro G2.

2016: The Pipistrel factory production line at the Duca d’Aosta airfield next to the town of Gorizia in Italy takes electric airplanes such as the two-seater Taurus Electro G2 and the hybrid-electric four-seater Panthera into the series production phase (Pipistrel).

The Pipistrel Panthera is a 4-seat “General Aviation”-class aircraft with three versions of propulsion: the gasoline-engine version, powered by a Lycoming IO-540 fuel injected engine; the hybrid; and the fully electric versions, for both of which the propulsion systems will be developed entirely by Pipistrel. Panthera also features all-electric systems for component actuation. Its titanium trailing-link undercarriage, flaps and trim are all electrically operated, resulting in low weight and maximum reliability by removing the need for complex and heavy hydraulic systems. All internal and external lighting is realized using state-of-the-art LED technology, providing for better clarity, recognition and feel. Panthera Hybrid will have a 145 kW hybrid-electric power train, supported by the state-of-the-art battery system and range-extender generator unit. Panthera Electro will have a pure-electric 145 kW able to cover 400 km (215 NM), quietly, efficiently, with absolutely zero emissions and for a fraction of cost. The platform is open and ready to accept future generations of battery technologies, which will increase the operating range.

In November 2016, at the China International Aviation & Aerospace Exhibition in Zhu Hai, Pipistrel announced a trade deal with Sino GA Group, a general aviation (GA) company in China, whereby eventually up to 500 electric and hybrid airplanes a year would be manufactured, the Alpha Electro and Panthera Hybrid models. The value of the seven-year project, which will include building new aircraft production facilities for both models, a runway, and a maintenance and training facility for both models in Jurong, Zhejiang Province and Yinchuan, is more than 500 million euros. The deal grants exclusive rights for the sales of the two aircraft models in Chinese territory and in the neighboring countries, namely Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Taiwan, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Korea and Mongolia. The contract also includes the delivery of 50 aircraft of each model, all required know-how on assembly of the two models, training of the personnel in Slovenia, implementation of the assembly process in new facilities in China, as well as supervision of newly established production to assure the same quality of the produced aircraft as the ones made by Pipistrel in Slovenia. Pipistrel will also use some of the money for the development of a new, ambitious zero-emission 19-seat airplane. It will be powered by hybrid electric technology and hydrogen fuel cells, and planned for public transport between the cities in China and all over the world.1

On November 15, 2015, Pipistrel CEO Ivo Boscarol, aged 60, was chosen as a member of the New Europe 100 list, a list of outstanding innovators from Central and Eastern Europe. This ranking is published annually by Res Publica together with the Visegrad Fund, Google and Financial Times. The founders explain that “only the people who have courage to think big, seek new ideas and show their skills have a chance to be listed.” In 2015 he was listed among the “Top 28 most influential people in the European Union” by Politico Magazine.

In December 2016, Pipistrel purchased a new 4200-m2 building for R&D. Still in Ajdovščina, the building, designed by architect Boris Podrecca, pioneer of postmodernism, has an underground garage for 40 vehicles and is energy-efficient. At the end of 2015, Pipistrel already had 89 employees, and by 2017 the number had been increased to 140, recruited from around the world, including the USA. Taja Boscarol, joint company owner with her father Ivo, confirmed: “We are also convinced that the future is electric—not just the future of aviation but the future of the entire transport on Earth.”2

From May 2017 the second step of the Hypstair project, MAHEPA (Modular Approach to Hybrid-Electric Propulsion Architecture), with funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, was launched at Pipistrel’s headquarters at Ajdovščina. Also taking part are Compact Dynamics, DLR, the University of Ulm, H2Fly, Politecnico di Milano, TU Delft and the University of Maribor. MAHEPA’s aim is to tackle current limitations of electrically powered aircraft by introducing new serial hybrid-electric power trains. The project will develop new components in a modular way to power two, 4-passenger hybrid electric airplanes scheduled to fly in 2020. The first will be equipped with a hybrid power train utilizing an internal combustion engine, and the second will be a fuel cell hybrid–powered aircraft. As with the exponential increase in the number of electric automobiles, provision must be made for recharging e-airplanes. In partnership with students from three universities, Pipistrel also developed the first taxi-up-and-plug-in public electric aircraft charging station, incorporating a computer, charging protocol, AC/DC converter, communication with owner’s cell phone, and WiFi. On September 30, 2017, the charging station at Pipistrel was used to charge an Alpha Electro, its battery fully charged in an hour. The station is capable of charging two aircraft simultaneously.

In December 2017, a Pipistrel Alpha Electro G2, delivered to a flight school at Pitt Meadows Airport, West Vancouver, Canada, was cleared for takeoff, while on January 2, 2018, at Perth’s Jandakot Airport in Australia, a G2, carrying Recreational Aviation Australia (RAAus) light sport aircraft registration 23-0938, made its first flight of two circuits. Passengers could soon be flying to Rottnest Island protected nature reserve in a lithium battery–powered electric plane if the idea takes off. Avinor with Norges Luftsportforbund (the Norwegian Air Sport Federation), in the country determined to become the first in which electric-powered airplanes take a significant market share, also acquired a G2. The British Civil Aviation Authority issued a BCAR A8-21 Organisational Approval Certificate for microlight aircraft design and manufacture to Pipistrel, the first company outside the United Kingdom to receive this.

During this time, Airbus, Europe’s giant airliner manufacturer, whose A320 airliner variants had sold in the thousands, had become fully involved with the French Cri-Cri airplane. With the official green light from given in October 2012, the demonstrator was renamed Airbus E-Fan. The new approach was for an airplane which used twin electric ducted variable pitch fans, spun by two electric motors powered by a series of 250 V Li-Po batteries (180 wh/kg). These were also linked to an electric drive for taxiing along the runway. The ducting increases the thrust while reducing noise, and when centrally mounted, the fans provide better control. The 120 assembled batteries weighed 137 kg (302 lb.); the weight of the airplane was 600 kg (1,323 lb.) at launch. Work began in earnest by an 18-strong team at ACS to prepare it to fly at the Paris Air Show at Le Bourget. Airbus Group Innovations concentrated on the e-FADEC system for managing energy and data flows within the plane. In 2013 E-FAN was presented at Le Bourget, but as a static exhibit. Its maiden and low-altitude flight, with Didier Esteyne at the controls, took place on January 30, 2014, at the Rochefort Airport. Its first higher-altitude flight took place on March 11 at Bordeaux-Mérignac International Airport, comprising a 29-minute flight to a height of 700 ft. Esteyne landing in front of a large applauding audience. On April 25, at an E-Aircraft day, the E-Fan was appreciated by the media, VIPs and France’s Minister of Industry, Arnaud Montebourg. Flight noise measurement tests were conducted in order to make the comparison with a conventional aircraft. It was then presented in flight during the Berlin and Farnborough Air Shows of that year.

Airbus Group now formed a subsidiary called VoltAir SAS in France to build a family of plug-in and hybrid-electric light airplanes, for which a factory would be built in the south of France. This would begin with a two-seat trainer called the E-Fan 2.0, slated to reach the market in 2018. A follow-on, hybrid-electric four-seater called the E-Fan 4.0, targeted primarily at buyers in the United States, would emerge soon after and is projected to go on sale in 2019.

On July 25, 1909, the world read about French pilot Louis Blériot’s crossing of the English Channel in his Type XI gasoline-engined monoplane. The publicity gained by this achievement brought the company orders for large numbers of the Type XI, and several hundred were eventually made. On July 7, 1981, pilot Steve Ptacek flew Solar Challenger across the English Channel. Now came the opportunity for a pure electric airplane to achieve the same feat. Pipistrel’s French dealer had been planning to make this crossing with an Alpha Electro when, it is reported, Siemens had abruptly warned the Slovenian team that they should not use its Dynadyn 60kW motor for overwater flights.3 Two Czech-built motors powered the Airbus E-Fan, and Didier Esteyne did have the same nationality as Louis Blériot. He has recalled:

At the end of May 2015, we began the test flights of E-FAN 1.1 to prepare it for its flight demonstrations both at the Paris Air Show and in particular for the “Channel Crossing.” On the afternoon of July 9th, a practice run enabled our reduced team, based at Lydd Airport in England, to “call” our device, the flight being followed by a rescue helicopter at sea, in which my friends Dominique and Paul were providing security by continuously scanning telemetry data transmitted by the E-FAN. A second helicopter would produce the video images for live transmission to the Control automobile located in Calais, in turn responsible for their broadcasting. A debriefing following this flight allowed each to confirm his role and his benchmarks. In 1909, Louis Blériot had taken off from a beach in Calais to reach England at Dover. We decided to make the crossing in the opposite direction to benefit from favorable winds and also allow both guests and spectators to be present at our arrival at Calais Airport.

The following day, Friday, 10 July 2015, at 10:15 a.m., helped by Francis, I am harnessed into the narrow cockpit with all the safety equipment, life jacket, oxygen mask, anti-smoke goggles … somewhat cluttered! At 10:00 the top start was given by a plane 15 minutes ahead of my flight with confirmation of the air traffic activity on the course. This was not a straight line between two points, but a navigation towards the Saint Inglevert field for the first leg of the course, in order to reduce the time over the sea and to land if one of the engines were to fail me. The first difficulty was to achieve a steady climb to the selected safety altitude of 3,500 ft, making the best possible use of the batteries and making sure to stay within the envelope of operating temperatures of the traction chain. A very precise point-of-no-return had been defined and confirmed permanently by the calculations of Dominique and Paul in the helicopter. My concern was not reaching France and having to turn back to Lydd. Weather conditions were almost perfect, except a little front wind at the end of the climbing time, temperature and visual conditions were great. All went well and I continued to follow the coastline. I could finally enjoy some flying and the scenery below. In Calais, Olivier and Romain were “glued” to the telemetry screen, following the flight data. The French coast is in sight at this altitude, and in the serenity of this moment, with a clear and turbulence-free sky, I was happy and surprised by the number of boats cruising under my wings! At regular intervals, Dominique, who was in radio communication with me and who was officiating as “Chef de Mission,” confirmed the parameters indicated on my dashboard and informed me of any discrepancies with the data provided.

At 10:47 a.m., I entered the safety zone of the Saint Inglevert airfield, and all being normal, I made a change of course with a left turn and continued towards Calais which I already had in my sights. After checking all the data with Dominique, and in compliance with our flight plan, I reduced power to make a gentle descent towards the next turning point, “BlériotPlage.” 10 minutes later, welcomed with enthusiasm by the airport control service, it was time to turn right towards the entrance of runway 06 with, as planned before the landing, a passage on the axis to greet the public. The altitude margin allowed me to accelerate up to 210 kph and the E-FAN glided obediently and without noise. Then with a tailwind, I slowed down, pulled out the train, the flaps, and almost reluctantly put down the electric bird and let it roll to the last exit lane.

With my arrival at the car park after 38 intense minutes and 74 km (46 mi) traveled, Jean Botti of Airbus welcomed me, happy and relieved. I just had time to observe that the calculated reserve of 19 percent of batteries remaining on arrival was actually 21 percent. I switched off all the contacts and jumped out of the cockpit to answer questions from the surrounding journalists. This is not the time to savor the adventure! Some people wanted to give me the title of “Hero.” I clearly refused; those who preceded us at the beginning of the last century agreed to go into the unknown, with everything still to understand, to conceive, to try, and it is through these “heroes,” their courage, their determination, that we are able to fly safely today. Although I was alone in the cockpit, ours was a team effort.4

But their glory was short-lived because it soon came to light that French pilot Hugues Duval had flown from Dover to Calais 12 hours earlier on Thursday in his Cri-Cri E-Cristaline, powered by two 35 bhp Electravia electric motors. By the beginning of 2014, about 70 aircraft had been equipped with French Electravia propulsion systems, including the MC30E Firefly in August 2011, and the electric motor-glider ElectroLight2.

According to the Associated Press, Duval’s flight took only 17 minutes, which was shorter than E-Fan’s flight because the latter aircraft circled Lydd Airport after taking off while a helicopter carried out a visual safety check. One difference in Duval’s flight that could have been a point of controversy is that he did not have formal permission to take off from Dover, so his aircraft was lifted into the air by a gas-engined Broussard monoplane called La Navette Bretonne. This assistance may place recognizing Duval’s record flight in jeopardy. Between March 2014 and February 2016, E-Fan had made a total of 117 flights including 39 in 2015.

On Friday, July 10, 2015, Didier Esteyne pilots the Airbus E-Fan out across the English Channel (G. Bassignac/Capa pictures–Airbus).

Airbus’s chief technical officer Jean Botti congratulates Didier Esteyne after his 2013 cross–Channel flight in E-Fan (G. Bassignac/Capa pictures–Airbus).

When Hugues Duval flew the Cri-Cri Cristaline across the Channel, he was given an airborne launch from a conventional Broussard monoplane called La Navette Bretonne (photograph: Jean-Marie Urlacher).

Russia has also decided to take the challenge of an electric airliner very seriously. This program is led by Alexander Inozemtsev, general designer of Aviadvigatel, and has brought together 100 enterprises of aviation, electronic and electrical industries and a number of leading academic institutes of the Russian Science Academy. A Tupolev Tu-214 (No. 64501) passenger jet will be used as a flying testbed for the “Integrated program for the creation of an all-electric aircraft.” Deadline: 2022. Inozemtsev was born on April 9, 1951, in the town of Kamyshin, in the Volgograd region of the USSR. In 1973, he graduated from Perm Polytechnic Institute and started working at Tupolev’s Engine Design Bureau (today OJSC Aviadvigatel) as a design engineer. The AEA program will use an experimental engine based on the PS90A turbofan developed by Aviadvigatel, which is currently used on the Ilyushin Il-96 and the Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214 series, as well as the Ilyushin Il-76 transport aircraft. The Tu-214E will have a single, centralized power supply system that provides all the energy needs of the aircraft. The pneumatic and hydraulic systems will be replaced with electric ones. The Zhukovsky Central Aero-hydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI), will be actively involved in the development project of the electric chassis that ensures taxiing airplanes without turning on the engine and the use of special trucks. The target for its first trials is 2025.5

Towards this end, a Russian octocopter has been made by NELK Company, equipped with hydrogen-air fuel cells developed by Yuri Dobrovolsky and a team at the laboratory of solid object Ionics of IPCP RAS (Russian Academy of Sciences), RAS Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics (IPCP). In January 2017 the Russian UAV set a world record for the duration of flight in open spaces during tests in Chernogolovka near Moscow. The 12 kg (26 lb.) octocopter remained airborne in poor weather conditions for 3 hours 10 minutes. With its 1.3 kW power plant, the fuel-cell drone can carry up to 0.5 kg (1 lb.). The record duration of the octocopter flight was achieved through the special design of membrane-electrode assemblies, which generate electricity through electrochemical reaction of hydrogen and oxygen and operate at extreme temperatures from -60 to +40 °C. The hydrogen-air fuel cells are formed on the basis of these assemblies. The development of innovative fuel systems that allowed the unit to stay in the air for such a long time had begun in 2015 in partnership with the Central Institute of Aviation Motors n. a. P.I. Baranov (TsIAM) and the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC). After the flight, Sergei Korotkov, chief designer for UAC, noted that this technology might be used in newer aircraft—medium-range MS-21 airliners and wide-body aircraft, developed in cooperation with foreign partners. Six months later, at MAKS-2017, the 13th International Aviation and Space Salon, held at Zhukovsky near Moscow, Korotkov, announced that a range of agreements on batteries to provide planes with new energy had indeed been signed.

In China, an aircraft similar to the stalled Yuneec GW430, the two-seater RX1E Ruixiang, with high-wing cantilever construction and long slender wings as developed by Shenyang Aerospace University in Shenyang City in Liaoning Province, northeast China, was ready for production as certified by the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC). Liaoning Ruixiang General Aviation Co. Ltd. had already built four RX1Es which had logged up over 240 hours total flight time. Similar to Pipistrel’s Alpha Electro, the RX1E has six 10 kW.h Kokam battery packs that can be removed for recharging. This feature allows flight schools to have pre-charged packs ready to swap once a student has made a final landing following a flight of 40 minutes at speeds of 150 kph (93 mph), and the ability to climb to 3,000 meters (10,800 feet) at a maximum takeoff weight of 480 kilograms (1,056 pounds). A battery pack can be recharged in an hour and a half. LRGA announced that they were ready the manufacture the airplane, starting with 20 more, then potentially increasing to 100 per year within three years.6 On November 1, 2017, with improved batteries, Shenyang Aerospace University’s two-seater RX1E-A made a two-hour flight from Caihu airport in northeast China’s Liaoning Province.

The Chinese RX1E, developed by Shenyang Aerospace University in Shenyang City in Liaoning Province, northeast China, created a lot of interest at Aero Friedrichshafen (photograph: Jean-Marie Urlacher).

However, large corporations have also become essential in developing the research needed to accompany the development of electric planes.

As recounted in Chapter One, in 1887 Siemens provided the electric motor for the Tissandier brothers’ Parisian aerostat. Now, 130 years later, they re-entered the challenge—to achieve a power-to-weight ratio of five kW/kg in a large electric motor. The R&D was headed by Dr. Frank Anton and Claus M. Zeumer in the eAircraft department of Siemens Corporate Technology. Support also came from the German Aviation Research Program LuFo in a project of Grob Aircraft of Tussenhausen-Mattsies in Germany. In 2013, Siemens, Airbus and Diamond Aircraft were able to successfully flight-test a series hybrid-electric drive in a DA36 E-Star 2 motor glider for the first time. The test aircraft had a power output of 60 kW.

Research continued from every conceivable angle. They began with some of their existing motors, testing all of the components individually, and reducing materials whenever possible. Engineers found that the aluminum endshield, the part of the motor housing that supports the bearing and protects the motor’s internals, was quite heavy. To reduce its weight, Siemens developed a sophisticated computer model of the endshield. The software represents the endshield as 100,000 separate parts and then simulates each element’s performance under various force conditions. At that point the algorithm conducts millions of trial-and-error simulations, eventually finding components that can be eliminated or reduced. The process helped engineers redesign the endshield, turning it into a filigree (lattice-like) structure with the same performance at less than half the weight. They also developed a prototype made from a carbon-fiber composite, to reduce the weight by another factor of two. Inside the motor, the rotor’s permanent magnets are configured into a Halbach array, which produces a stronger magnetic field with less material. The stator is made of an easy-to-magnetize cobalt-iron alloy. The motor’s windings are surrounded by a special cooling liquid that conducts heat but not electricity. Lead engineer Dr. Frank Anton said, “We use direct-cooled conductors and directly discharge the loss of copper to an electrically non-conductive cooling liquid—which in this case can be, for example, silicone oil or Galden.”

The revolutionary Siemens engine weighs just 50 kg (110 lb.), and delivers a continuous output of about 260 kW (photograph: Jean-Marie Urlacher).

By 2015, Siemens had arrived at a unit weighing just 50 kg (110 lb.), and delivering a continuous output of about 260 kW—five times more than comparable drive systems. The electric motors of comparable strength that are used in industrial applications deliver less than one kW per kg. The performance of the drive systems used in electric vehicles is about two kW per kg. Since the new motor delivers its record-setting performance at rotational speeds of just 2,500 revolutions per minute, it can drive propellers directly, without the use of a transmission. The motor began flight-testing at the end of 2015. In the next step, the Siemens researchers planned to boost output further. Frank Anton stated, “We’re convinced that the use of hybrid-electric drives in regional airliners with 50 to 100 passengers is a real medium-term possibility. The technology will apply first to regional airliners flying 50 to 60 passengers over stage lengths of up to 600 miles (1,000 km).”

X57’s DEP system has been tested at NASA’s Armstrong center in California using the HEIST (Hybrid Electric Integrated Systems Testbed), capable of accommodating systems that use up to 100 kilowatts of power, mounted to a modified truck. The first tests were made in 2014 on the energy-efficient Pipistrel Electro Taurus electric propulsion system (NASA).

Before long, as part of the Hypstair project, managed by Pipistrel, a Siemens e-motor and a Rotax combustion engine had been installed on a Pipistrel Panthera prototype at that firm’s factory in Ajdovščina, Slovenia. On February 9, 2016, the world’s first power-up of a hybrid propulsion system on a four-seater took place. Additional partners in the project are the University of Maribor (Slovenia), the University of Pisa (Italy), and M.B. Vision (Italy). The motor was run in electric-only mode, using battery power; generator-only mode; or hybrid mode combining the two. For the initial testing, a five-blade, low-rpm propeller was attached to the motor.

Another airplane to benefit from the Siemens engine was the eFusion, a two-seater, side-by-side low-wing monoplane with nonretractable tricycle landing gear. Built by Magnus Aircraft led by ImreKatona at Kecskemét, Hungary, eFusion made its maiden flight at Matkópuszta airfield on April 11, 2016. The empty weight of 410 kg includes the batteries and the ballistic recovery system. The aircraft has a maximum takeoff weight of 600 kg. Siemens designed a safe and robust battery system for aviation use and optimized the electric propulsion system for application in the cost-sensitive segments of Very Light, Light Sport and Ultra Light Aircraft. Frank Anton of Siemens saw the eFusion as a flying test bed for our further battery system optimization, developed by their Budapest-based subsidiary in close cooperation with the German colleagues at Siemens’s headquarters. eFusion’s aerobatic capability will contribute to the training of the much needed new generation of airliner pilots.

In September 2016, it was announced that Tianshan Industrial Group, based in Shijiazhuang City, Hebei province of China, had formed a joint venture with Kecskemét’s Magnus Aircraft to manufacture the eFusion 212. Under the €30m deal, the two companies plan to create a joint enterprise at the central Hungarian city of Kecskemét, where Magnus Aircraft is based, to build light planes under license for sale in China. Initially, the new partnership is expected to construct and to sell a total of 1,500 of the eFusion 212 aircraft by 2020. It also includes a greenfield investment scheme with the construction of a medium-sized airport in Kecskemét, an assembly and maintenance plant, and the Magnus Pilot Academy training center network. Magnus Aircraft anticipates employing up to 600 people at its factory in Hungary and an additional 250 in China. In May 2017 a center was also built at Gillespie County Airport, Fredericksburg, Texas, for both pilot-training and distribution of the Magnus eFusion 212. It is anticipated to export the eFusion airplane to China from 2018. Within six years, it predicts it will attract sales revenues totaling more than €162m through the latest deal as the plant gears up for capacity expansion.7

In June 2017, Solar Ship linked up with Chris Heintz, CEO of Zenith Aircraft Co. in Midland, Ontario, to convert the existing Zenair STOL (Short Take-Off and Landing) CH750 aircraft into an electric bush plane. This new aircraft would provide extreme short takeoff and landing (XSTOL) capability enabling pilots to take off in areas without runways. The aircraft is recharged by either a battery swap or electric vehicle rechargers. It will not use any fossil fuel and will be available as a bush plane, float or amphibious. The electric bush plane project is part of Zenair and Solar Ship’s ongoing partnership since 2011, when Zenair developed the fuselage for Solar Ship’s Zenship 11. Established in 1974, Zenair has designed more than 15 aircraft with sales in more than 50 countries.

In August 2017, Boeing confirmed a small experimental “X-plane” hybrid-electric demonstrator planned for the early 2020s could signal an unprecedented push into the commuter market. The X-plane plan is being evaluated as part of the company’s EcoDemonstrator technology testbed series and, if successful, could open the door to a new generation of small Boeing airliners seating 12 to 50+. It would use a Brazilian-produced biofuel blend made up of 10 percent biokerosene and 90 percent fossil kerosene, the maximum mixture according to international standards. Studies have shown that sustainably produced aviation biofuel emits 50 to 80 percent lower carbon emissions through its life cycle than fossil jet fuel emissions.

But the research is not only useful for smaller aircraft: Airbus now announced that it had signed an agreement with German industrial conglomerate Siemens to develop hybrid planes that can carry up to 100 passengers. The aircraft would use a combination of electric power and conventional fuel. The hybrid Airbus planes would consume 25 percent less fuel and would be almost silent during takeoff and landing, when running on electric power, according to Siemens. At cruising altitudes, the planes would be powered by jet fuel. The planes are expected to have a range of about 620 miles (1000 km), enough to fly from New York City to Detroit. As a start, the Euro duo set about building E-Aircraft System House, a large development and test facility near Munich, where the new systems would be developed by 200 engineers. Ground was officially broken on the facility in spring 2016, enabling the start of construction in early 2017 and a planned opening by late 2018.

As part of the Goodwood Festival of Speed, held between June 29 and July 2, the eFusion, piloted by Frank Anton with Siemens UK chief executive Juergen Maier on board, took to the skies in the first-ever extended all-electric propulsion 30-minute flight over a United Kingdom airfield. Several flights were made.

Frank Anton and the Siemens team had also been working with Extra Flugzeugbau (Extra Aircraft Construction), a manufacturer of aerobatic aircraft, directed by Walter Extra. Extra, born in 1954, trained as a mechanical engineer, then began his flight training in gliders, transitioning to powered aircraft to perform aerobatics. He built and flew a Pitts Special aircraft and later built his own Extra EA. Extra began designing aircraft after competing in the 1982 World Aerobatic Championships. His aircraft constructions revolutionized the aerobatics flying scene and still dominate world competitions. In April 2016, Extra unveiled the aerobatic 260 kW Siemens-engined 330LE (D-EPWR) at Aero Friedrichshafen. Two months later, the 330LE, weighing 1,000kg (2,200 lb.), its battery management specially prepared by a Pipistrel team, made its first 10-minute flight, then on July 4, its first public flight, at Schwarze Heide Airport near Dinslaken, Germany. It was then used as an ongoing flying test bed to test its limits for the Siemens system.

Others would soon install a Siemens in their airplanes. The Hamilton aEro aerobatic plane is sponsored by the Hamilton Watch Company, part of the Swatch Group, a watch company based in Bienne, Switzerland. On October 2, 2016, the Hamilton aEro, piloted by Red Bull air racer Nicolas Ivanoff, Hamilton’s brand ambassador, took off from Raronairfield 75 kilometers south-southeast of Berne in Switzerland, for its first public flight. The project’s founders are Air Zermatt pilot Thomas Pfammatter and aerobatic paragliding champion Dominique Steffen of Hangar 55, along with former Solar Impulse members Sebastien Demont and Gregory Blatt. They took a Silence Twister aircraft and fitted it with a Siemens electric motor, its energy coming from 160 kg of Renata high-capacity 200 Wh/kg batteries. In the sponsor’s orange-and-white livery, the tailplane and the wings of the Hamilton aEro1 carry the logo of a black watch face with white hands. Maximum flight time is said to be 60 minutes, with 30 minutes of aerobatic flight plus a reserve. Soon after, Hangar 55 announced its goal to use the Twister in the 2017 Red Bull Air Race as an exhibition. They speculated that this might be a prelude to an all-electric junior class with all pilots using identical Twisters. In April 2017, after aEero 1 had completed 50 flying hours, it was announced that Solar Impulse co-pilot André Borschberg had joined the team. H55 is also supported by the Canton of Valais, in particular the Ark Foundation, and the Federal Office of Civil Aviation (FOCA). On September 21, 2017, the Hamilton. H55 Silence Twister made its maiden flight at Raron in the Valais, 130 km (80 mi) east of Geneva.

The Hamilton aEro aerobatic electric aircraft has a maximum flight time of 60 minutes, with 30 minutes of aerobatic flight plus a reserve (photograph: Jean-Marie Urlacher).

Max Vogelsang of MSW Aviation in Wohlen, in the canton of Aargau in Switzerland, has teamed up with the Bern University of Applied Science in Burgdorf to produce the detachable-wing MSW Votec Evolaris, Switzerland’s first electric aerobatic aircraft. With 221 kW of power, the Votec 221 has planned autonomy of 20 minutes but a roll-rate of 460° per second. Takeoff roll distance is 50 m and rate of climb when fully charged is 2.5 m/s. Evolaris can run at full throttle for 11 minutes on one charge. First prototype tests took place in spring 2017, with aerobatic tests in the autumn.

While Marc B. Corpataux of Alpin Air Planes GmbH, who is also the Swiss distributor for Pipistrel, presented his concept for an airfield network for training and travel in Switzerland, Lojze Peterle, a member of the European Parliament who is also a pilot, confirmed that Brussels supports the move towards cleaner energy and will work towards changes that will enable electric flight and make it simpler. Corpataux received the E-flight award from Willi Tacke, the man behind the AERO e-flight-expo and the editor of Flying Pages. Following this, the first-ever application for a certification of an electric aircraft was filed, for the Pipistrel Alpha Electro in the category CS LSA. Events such as the first E2Flight Symposium held at the Stuttgart Airport further encouraged the exchange of ideas.

Meanwhile, the Siemens-engined Extra 330LE had been tuning up its act. On November 25, 2016, Walter Extra took off from the Dinslaken Schwarze Heide airfield and reached a height of 3,000 meters (1,000 feet) in just four minutes and 22 seconds—equivalent to a climbing speed of 11.5 meters (37.7 feet) per second. In this he beat the previous world record set by Chip Yates in 2013 by one minute and 10 seconds.

Siemens is not alone. In 2014, Joachim Geiger and his team in Bamburg installed one of their HPD 25D engines in an 11-m wingspan Elektra One aircraft from PC-Aero. This engine, weighing just 10 kg (22 lb.), provides a maximum 30 kW and 26 kW continuous power. Tandem rotors on either power plant can run independently, enabling economical flight on one rotor, or a “get-home” mode at half power that will at least stretch the glide in the event of one rotor or controller failing. Based on this unit, in 2016, Acentiss of Ottobrunn created two aero engines developing 32 kW and 40 kW. By November, they had installed one in a solar-electric ultralight called Elias, complete with retractable tricycle landing gear. Elias is optionally piloted carrying test gear so that it can also be monitored by an Acentiss Ground Control Station (GCS). A dSPACE MicroAutoBox is used as the onboard flight guidance computer, because it provides a direct interface to MATLAB Simulink so modifications to the control algorithms can be implemented quickly. Depending on whether a pilot is on board, the system can monitor and control, by visual or data transmissions, the mission based on pre-set plans or manual overrides. It can check the multi-spectral, high-definition sensors on board Elias and record their output.8

A Belgian start-up, Green Tech Aircraft (GTA) of Leuven, announced the development of their Ypselon GT, a build-it-yourself electric airplane for flying enthusiasts. With its rear-mounted pusher propeller, the Ypselon GT will have a maximum capacity of two people and an extra carrying capacity of 220 kg (485 lb.). It may achieve speeds of up to 320 kph (200 mph).

In France, a team working at ONERA (the French National Aerospace Research Laboratory), led by Claude Le Tallec, began to develop a Distributed Electric Propulsion airplane, called the Ampère, after André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836), physicist and mathematician, who gave his name to the amp. The 6-passenger French version will be equipped with 32 electric engines powered by a fuel cell. A one-fifth-scale model was built by Aviation Design of Milly-la-Forêt, with a full-scale roll-out due in the mid–2020s.

But France was not alone. Dr. Mark Moore of NASA wrote a paper, “The Coming Era of Distributed Electric Propulsion—and What It Means”:

NASA Langley is pioneering the integration of a new propulsion technology that has the potential to transform aircraft capabilities, the missions they fly, and the way we interact with aviation. The largest aerospace technology shift since the invention of the turbine engine is taking place, and will quickly sweep through the shorter range aviation markets. The result will be a step change in the degrees of freedom available to aircraft designers to achieve digital aircraft systems that achieve capabilities long dreamt of—but previously out of reach. Advanced concepts utilizing this technology will be showcased as vision vehicles that incubate technologies along two vibrant convergent frontiers, electric propulsion and autonomy. Study results will focus on the application of electric propulsion, not only as a new propulsion technology, but as a mechanism for achieving highly coupled digital aircraft systems that ride the wave of self-driving vehicles, sensor fusion, smart materials, and multi-functional systems. The opportunities are unfolding for a new aviation renaissance where multi-disciplinary synergistic coupling opens up entirely new design space to explore.9

The realization of this approach has been taking the form of the NASA SCEPTOR X-Plane X-57, named Maxwell after 19th-century Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell. It will be the first manned Distributed Electric Propulsion aircraft, capable of achieving a 5x reduction in energy consumption of a general aviation aircraft at the high-speed cruise condition. To realize this, in 2014, NASA teamed with two small think-tank-style technology companies in California: Empirical Systems Aerospace (ESAero) in Pismo Beach, and Joby Aviation in Santa Cruz. An earlier NASA collaboration with Joby had produced the Lotus, an all-electric UAS with a set of two-blade rotors at each wingtip and one hinged propeller on the leading edge of the vertical tail. Project Sceptor (Scalable Convergent Electric Propulsion Technology and Operations Research) would be a test aircraft, evaluating the use of distributed electric propulsion (DEP). It involves replacing the wings on a twin-engined Tecnam P2006T (a conventional four-seater light aircraft) built in Capua, Italy, and replacing them with a Leading Edge Asynchronous Propeller T.

In November 2014, a facsimile of the concept vehicle’s wing, mounted on a truck bed for dynamic testing of its low-speed lift systems, arrived at NASA’s Armstrong center in California. The acronym department came up with HEIST, for Hybrid Electric Integrated Systems Testbed, aka Airvolt. The Peterbilt truck provides a platform that can test the towering contraption at the speeds typical of landing and takeoff technology incorporating a (Leaptech) aerofoil equipped with 14 electrically driven five-bladed propellers. Made of steel and aluminum, it is 13.5 feet (4 m) tall. The first tests were made on the energy-efficient Pipistrel Electro Taurus electric propulsion system, which is typically used for motor-gliders. The Pipistrel motor is powered by lithium-polymer batteries and produces 40 kilowatts of power, which are monitored by the Airvolt that is capable of accommodating systems that use up to 100 kilowatts of power. The test stand can also withstand 500 pounds of thrust. Next up for the Airvolt are tests during late summer on the Joby Aviation JM-1 motor that will provide information for modeling simulations of the electric propulsion elements.

During takeoff and landing, Maxwell will make use of all 14 motors to create sufficient thrust, but once it’s up in the air it will only use the two larger cruise motors located on the tips of the wings. The contoured lift propellers will fold inward and fit snugly against the prop shaft recesses in their extended hubs. In that position, the cruise propellers would be immersed in the wingtip vortex, which will increase their efficiency. R&D for a 500 kW nine-passenger aircraft was scheduled from 2017 through 2019. NASA Administrator Charles Bolden stated, “This will be NASA’s moonshot for aviation.” In the U.S. President’s Financial Year 2017 budget, NASA received $790 million to fund New Aviation Horizons, among other similar green-aviation initiatives. That summer of 2016, NASA continued testing the wild new wing technologies.

Maxwell has already won converts. Cape Air, a Barnstable, Massachusetts–based independent regional airline, is working with NASA and the Italian manufacturer to incorporate practical considerations in the design. Cape Air operates a fleet of mainly nine-seat Cessna planes flying short routes, such as from Boston to Nantucket, Massachusetts.

“They have almost perfected traditional commercial jet engines as far as they can go,” said Cheryl Bowman, co-technical lead of the aircraft gas-electric propulsion program at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio. In 2015 NASA wrapped up a six-year initiative called the Environmentally Responsible Aviation project, in which researchers worked to document several possibilities for improving fuel efficiency of aircraft. Among the proposals were switching to a lighter composite material for building the body of the planes, and shifting turbines to the back of the plane as part of a wing-streamlining shape. That’s not taking into account the possibility of hybrid propulsion systems. Some of the work in that area goes so far as to propose demonstrating all-electric propulsion systems in smaller, aviation-class planes. “The power can either come from something like a battery or a fuel cell or something like that, or it could come from a generator run by a turbine,” said Ralph Jansen, the other co-technical lead on the research project at Glenn Research. NASA is working with a long list of corporate partners such as Boeing, General Electric and Rolls-Royce, as well as Ohio State University, the University of Illinois, and Georgia Institute of Technology, to develop different concepts for improving aircrafts’ fuel economy, according to Bowman. One concept is a commercial plane about the size of a Boeing 757 that adds extra electricity-powered propulsors along the length of the aircraft. Researchers have put the fuel savings of the design at 7 to 12 percent.

In July 2016 the Tecnam P2006T, wearing a NASA livery, was uncrated and slowly rolled out. By October, in order to hit its ambitious ten-year goal, NASA announced a new research wing at the NASA Glenn Research Center’s Plum Brook Station, a 6400-acre (2,600-hectare) remote test installation site near Sandusky, Ohio. The unique NEAT (NASA’s Electric Aircraft Testbed) began with a 600-volt power source to test an electrical system that could realistically power a small one- or two-person aircraft. The short-term goal was to turn NEAT into a flexible testbed that could build and test power systems for even larger passenger aircraft without having to crash anything in the process. The long-term goal, however, would be to create a 20-megawatt power system that will be light, yet powerful enough to actually get off the ground. Dr. Roger Dyson and the team for hybrid gas-electric propulsion began work to make the testbed more efficient and lightweight.

As part of the X-57 program, a six-percent scale model of a Boeing BWB (Blended Wing Body) was tested for six weeks in the 14-by-22-foot subsonic tunnel at NASA’s Lang-ley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. The BWB is triangular in shape: the wings are merged into the body, and there is no tail. Its traditional name is the Flying Wing, theoretically the most aerodynamically efficient (lowest drag) design configuration for a fixed-wing aircraft. The first flying wings were developed over one hundred years before. The top of this NASA BWB was painted in nonreflective matte black to accommodate laser lights that swept across the model in sheets. NASA and Boeing researchers used those laser sheets combined with smoke in the technique known as particle imagery velocimetry, or PIV. This would map the airflow over the model. From December 2016, NASA test pilots and engineers began to “fly” an interactive simulator designed to the innovative specifications of the X-57 Maxwell. Meanwhile, the Tecnam P2006T was undergoing conversion at Scaled Composites in Mojave, California. The aircraft’s two inboard engines were being modified to feature an electric system, and could undergo taxi tests in early 2018.

But with the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as 45th President of the USA in January 2017, it was announced that the incoming administration planned to strip NASA’s earth science programs of funding as part of a crackdown on “politicized science,” which may well include the X-57 program. On February 20, the U.S. Senate passed legislation cutting funding for NASA’s global warming research. The House was expected to pass the bill.

On June 8, 2017, Sean Clarke, X-57 Principal Investigator, NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center, speaking at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics’ Aviation 2017 conference in Denver, stated that the battery packs, providing 47 kWh of energy and weighing close to 900 lb. (400 kg), an increase of more than 10 percent over the original goal, were posing the biggest challenge so far. “They have used up our mass margin,” Clarke reported.

Mod IV, which is currently being reviewed for funding, is where the X-57 completes its transformation to a full-fledged efficient electric aircraft. After Mod III flight tests, electrical engineers will work to pull off the dummy pylons and replace them with the 12 high-lift electric motors, similar to what were on the semi back in Mod I. With 14 motors total, 12 just to provide lift on takeoff and landing, the X-57 Maxwell will be ready for test flights over the dry lakebed at Edwards as soon as 2020 or 2021. If these prove successful, the X-57 could result in a five-time reduction in the energy required for a private plane to cruise at 175 mph (280 kph). While waiting for batteries with sufficient energy density, the X-57 may use diesel-sourced hydrogen fuel cells, taking it from 40 minutes of flight to about three and a half hours.

Meanwhile, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is sponsoring the Vertical Take-Off and Landing Experimental Aircraft (VTOL X-Plane) program to demonstrate an electric VTOL aircraft design that can take off vertically and efficiently hover, while flying faster than conventional rotorcraft. In April 2016, Aurora Flight Sciences of Manassas, Virginia, was selected, having demonstrated their scale model LightningStrike. Led by founder John S. Langford III, Aurora, working with Rolls-Royce and Honeywell, is currently aiming at completion of the full-scale aircraft. The plane has a bullet-shaped fuselage and two boxy wings holding a bank of 24 ducted fans—18 distributed within the main wings and six in the canard surfaces, with the wings and canards tilting upwards for vertical flight and rotating to a horizontal position for wing-borne flight at more than 400 mph (640 kph). Following proof of concept, work on the fullscale XV-24A went ahead, with ground and flight tests taking place during 2017 and flight testing in September 2018.

And it is not just propulsion that is attracting research. Others are looking to make a “more electric” aircraft. SPEC (Safran Power Electronics Center) is looking an aircraft that is more economical, more reliable, and less polluting. The idea behind a more electric aircraft is to gradually introduce electrical systems to replace onboard hydraulic and pneumatic systems used to power the landing gear, brakes, flight controls and thrust reversers, as well as for cabin pressurization and to start the engines. A key area of research for more electric involves the switch from alternating-current (AC) to direct-current (DC) power distribution, to allow exchanges of energy between equipment. For this a modular rig called Copper Bird (“Characterization & Optimization of Power Plant & Equipment Rig”) has been set up in Paris to test the stability of onboard electrical networks, and simulate the integration of different electrical systems and equipment. It also measures power quality and network stability. In more general terms, it can be used to demonstrate the maturity of systems and technologies developed for “more electric” aircraft.

In May 2017, Centennial College in Toronto, Canada, received $2.3 million in funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to collaborate with Safran towards the next generation of electric-actuated landing gear for energy-efficient aircraft. Safran has also developed an electric taxiing system, which will enable aircraft to taxi at airports without using their jet engines or requiring special tractors. By September, Safran Landing Systems was meeting with airlines to present its electric green taxiing system; for Airbus, the system would be used for the A320 family. Safran Center of Expertise, Safran Power Units is also developing a fuel cell for the PIPAA project (for fuel cells for aeronautical applications) for the power supply of aircraft systems, including electric ground taxiing solutions. It should be completed by 2019–2020.

From 2010 the Japanese aero engine manufacturer IHI, formerly known as Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries Co., Ltd., teamed up with Boeing to carry out research into regenerative fuel cell technology to provide electrical power for airplanes. The technology, part of the More Electric Architecture for Aircraft and Propulsion (MEAAP) project, would reduce the load of the aircraft’s onboard electrical supply and allowing for smaller, lighter power generation systems. This in turn could potentially reduce weight, fuel burn and CO2 emissions. There was a further environmental benefit, as the only by-product of regenerative fuel cells is water. When climbing or cruising, more electrical power than is required is generated. Regenerative fuel cells use that surplus energy to break water down into oxygen and hydrogen, which is then stored and used to produce electricity when supply falls short. IHI anticipated that applications would include power for galleys, pumps and lighting, but that a prototype regenerative fuel cell would be ready for ground testing within two years. It planned to carry out in-flight tests using regenerative fuel cells to provide auxiliary power by the end of 2013, and an all-electric system for the engine and aircraft of the future within the next decade or two.

The realization of this research began to emerge in the modifications to Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner. Virtually everything that had traditionally been powered by bleed-air from the twin engines had been transitioned to an electric architecture, with electrically powered compressors and pumps, while completely eliminating pneumatics and hydraulics from some subsystems, e.g., engine starters or brakes. Electric brakes significantly reduce the mechanical complexity of the braking system and eliminate the potential for delays associated with leaking brake hydraulic fluid, leaking valves, and other hydraulic failures. The total available on-board electrical power is 1.45 megawatts, which is five times the power available on conventional pneumatic airliners. It is also enough electricity to power 31 average American households with all lights, ovens, furnaces and water heaters turned on to full, or 1,160 homes at average loads. The most notable electrically powered systems include: engine start, cabin pressurization, horizontal stabilizer trim, and wheel brakes. Like all aircraft, the Dreamliner has a triple-redundant system to move its control surfaces. Unlike other aircraft, two of them are electric, using motors in the wings to move the control surfaces. The third is a hydraulic system, compartmentalized with valves, and pressure is maintained using electrical compressors. The air conditioners use electrical heaters and electrical compressors. Electricity from the airport’s ground power supply, or the aircraft’s new massive lithium-ion battery banks, is used to electrically spin up the engines before they can be started. Wing ice protection uses electro-thermal heater mats on the wing slats instead of traditional hot bleed air. The research is ongoing for the next stage: electric self-taxiing by 2020; electric landing gear actuation system; electro-hydraulic flight control actuator; electro fuel pump system; electro oil pump; and an embedded starter-generator.

That lithium batteries can be inflammable was shown in July 2013, when an Ethiopian Airlines–operated Boeing 787 Dreamliner caught fire while on a remote parking stand at London’s Heathrow Airport. According to the report by Air Accidents Investigation Branch, the fire was probably caused by wires for an emergency beacon’s lithium-metal battery being crossed and trapped under the battery cover, which probably created a short-circuit. Three months later, a lithium-battery-electric Tesla Model S automobile caught fire after hitting metal debris on a highway in Kent, Washington. Such rare accidents can give a remarkable technology a poor reputation in the public mind.

In the pursuit of making all aspects of aviation electric, some are looking not only to innovation in planes, but in airships. In June 2016, France announced another plan for a commercial electric airship. Descended from France’s Tissandier brothers’ electric aerostat of 1883, one hundred and almost thirty years later, in 2012, a French firm called Flying Whales, founded by engineer Sébastien Bougon of Levallois Perret, has teamed up with Europe’s leading ultracapacitor manufacturer Skeleton Technologies, led by TaaviMadiberk, in a program to build a 60-ton Large Capacity Airship, or LCA60T, for the global transport market. Skeleton Technologies is the only ultracapacitor manufacturer to use a patented nanoporous carbide-derived carbon, or “curved graphene,” delivering twice the energy density and five times the power density offered by other manufacturers. The main advantage of the LCA60T airship will be its ability to transport heavy and oversized cargo of up to 60 tons in its 250-ft (75-m)-long underbelly, at speeds of 60 mph (100 kph), with a range of several thousand kilometers per day. The helium-filled, rigid-structure airship will be capable of winching to pick up and unload cargo while hovering, at a fraction of the cost of a heavy-lift helicopter, and for much heavier loads. Without the need to make conventional takeoffs and landings, energy consumption via its hybrid electric propulsion system will be low. Skeleton Technologies will join the program to help design and build hybrid propulsion for the LCA60T’s electric power systems. Average operational power is expected to be approximately 1.5 MW with the company’s graphene-based ultracapacitors assisting to cover the additional 2 MW peaks for hovering, lifting and stabilization in reasonable and turbulent environments. LCA60T will not require an airport or any kind of runway to operate, opening up new markets across the world for industries that require heavy-lift or oversize cargo options, across terrain lacking in infrastructure. It will be able to transport logging timber from remote locations, but that also means being able to deliver large items like wind turbines or electricity pylons in one piece to the side of a mountain, for example. It could also move prefabricated houses or building modules across undeveloped terrain or transport large aircraft components from one supply chain location to the next.

The program is part of the French government’s “Nouvelle France Industrielle” plans for future transport, with the country’s forestry agency highlighting the need for LCA60T to extract timber cargo. Other plans by the NFI include building at their Future Aeronautical Factory and selling 80 two-seater electric trainer aircraft by 2020.

In 2015, Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang and French Prime Minister Manuel Valls oversaw the signing of a cooperation and investment framework agreement between Flying Whales and the China Aviation Industry General Aircraft (AVIC General) company, which is to become a Flying Whales significant shareholder. The project will involve a consortium of about 30 companies and labs to cover the research and development, engineering, industrialization and manufacturing phases of the program. The first phase of engineering was completed by 2016. Industrial production is expected to start in 2021.10

As of 2018, French Air Base 125 at Istres–Le Tubé, northwest of Marseilles, and its gigantic hangar Mercure (160 m long, 38 wide and 25 high) will be ready to receive the first prototypes of the LCA60T. Mercure hangar will also see the construction of the Stratobus, an autonomous stratospheric airship, 100 meters long by 33 meters maximum diameter. The airship will be positioned at an altitude of about 20 kilometers (12 miles) over its theater of operations, in the lower layer of the stratosphere, which offers sufficient density to provide lift for the balloon. Winds at this altitude are moderate and stable throughout the entire zone between the tropics, at not more than 90 kph (55 mph), allowing the airship to remain stationary by using its electric propulsion system. Stratobus will carry payloads to perform missions such as the surveillance of borders or high-value sites, on land or at sea (video surveillance of offshore platforms, etc.), security (the fight against terrorism, drug trafficking, etc.), environmental monitoring (forest fires, soil erosion, pollution, etc.), and telecommunications (Internet, 5G). With €17 million in French government funding, Thales Alenia Space, a joint venture between the French aerospace group Thales and the Italian group Leonardo, is the lead company, and also in charge of systems integration, avionics, solar arrays and certification. CNIM (Construction Navale Industrielle de la Méditerranée), located in Seyne-sur-Mer, will build the structure and associated equipment, the ring and the nacelle, while Solutions F, based in Venelles, will provide the electric propulsion system, Airstar Aerospace the fully-dressed envelope, and Tronico-Alcen the energy conditioning system. In addition to these French partners, Cmr-Prototec of Norway will supply the energy storage system and MMIST of Canada the parachutes. Stratobus has been endorsed by the Pégase competitiveness cluster, in charge of launching a dirigible industry in France. At the June 2017 Paris Air Show, Thales Alenia Space announced that it had entered into a minority shareholding agreement in Airstar Aerospace, the European leader in the design and manufacture of stratospheric balloons, among others. Stratobus would gather the expertise of several small or medium groups, especially from Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur. Thus Solution F would be in charge of electric propulsion, while CNIM would be in charge of the equipped structure, the ring and the nacelle. As a reminder, the R&D program was launched in April 2016. Models will now be constructed, tests carried out for definitions, the objective being to be ready for a first demonstrator by 2018. The demonstrator will be small scale, 40 meters (130 ft) long by 12 meters (40 ft) in diameter, against 100 meters (328 ft) long and 33 m (100 ft) in diameter in its definitive version.

The Stratobus program kicked off officially on April 26, 2016, with three major program milestones. The first is the SRR, or System Readiness Review, which aims to consolidate the concept’s specifications. The SRR was passed in December 2016. The next phase, the PDR, took place in mid–2017, resulting in a concept that meets the defined specifications. At the June 2017 Paris Air Show, Thales Alenia Space announced that it had entered into a minority shareholding agreement in Airstar Aerospace. The definitive version should take to the air by 2020 for a five-year flight.

Across the Pond, in 2013, DARPA and the USAF selected Lockheed’s Skunk Works division over a rival bid from Northrop Grumman Martin to build Isis, a one-third scale unmanned airship demonstrator, powered by solar cells and fuel cells, that would be capable of operating at 21 km (13 mi) altitude for up to 10 years at a time, with radar technology so powerful it could spot a car hidden under a canopy of trees more than 300 km (180 mi) away. The energy cells must be capable of generating enough power to operate the radars, navigation system, communications gear, and the electric motors that will turn the airship’s giant propellers. Both demonstrator sensors are significantly smaller than the envisioned operational system, which is expected to occupy an area 6,000 square meters (2.32 mi2) across. Such an airship could revolutionize the way oil and mining companies haul equipment to the Arctic and other remote areas without roads. The airship should be certified by the Federal Aviation Administration by late 2017, paving the way for initial deliveries in 2018.

In Ontario, Jay Godsall, a biotechnology entrepreneur, has set up Solar Ship to build solar-powered triangular blimp-like flying machines that could serve as lifelines to the world’s most remote places. Solar Ships range from an 11-meter-wide wingspan-envelope to a projected 100-meter (328 feet)-wide monster that could carry up to 30,000 kilograms (66,000 pounds) for a minimum of 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles). While Solar Ship Inc.’s head office is in Toronto, its operations are in Brantford, Ontario, Cape Town, Lusaka, Kampala and Shenzhen. In September 2016, Manaf Freighters purchased four Solar Ship aircraft. On June 29, 2017, Solar Ship completed the first in a series of flights to develop a fossil fuel–free transport and logistics system for Canada’s North. Solar Ship is working with Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) as part of project to support the Department of National Defence.

On July 26, 2016, Dr. Peter Harrop, Chairman of IDTechEx, gave a Webinar titled “Electric Aircraft Reach a Tipping Point.” He observed: “About 20 companies make or will soon make electric aircraft. Nearly all are pure electric and fixed wing, the motorized hang glider and the self-launching sailplane being typical with one hour endurance. A bigger value market being addressed is training planes and bigger still will be hybrid fixed wing and vertical take-off aircraft hybrid and pure electric with the pure electric ones only managing 30 minutes. In this webinar we discuss possible uses, improvements and other types too.”

It is now clear that the manned electric aircraft (MEA) business will be around $24 billion as soon as 2020, but the new analysis by IDTechEx sees truly hybrid and pure electric aircraft being a $24 billion business in 2031. Half of that will be relatively low-priced craft such as leisure and small work aircraft, and the high-priced half will be a mix of such things as helicopters, military aircraft and feeder aircraft, according to IDTechEx projections, with large airliners not quite there. “Manned Electric Aircraft 2016–2031” reveals how much of this will no longer be a reworking of land-based technology but will be based on such things as superconducting power distribution and traction motors with at least four times the kW/kg and Distributed Electric Propulsion (DEP) along the full length of the wing. However, new concepts being developed first on land, such as supercapacitor body work and some other structural electronics, may have a place in these new ultra-lightweight aircraft.

Spreading the word on the new craft and new technologies has seen the growth of more air shows around the world, enabling the public to learn of the advances being made for the industry to share ideas.

EAA’s annual AirVenture took place at Oshkosh in July 2016, but visitors hoping to see electric aircraft flying were disappointed. While manufacturers or would-be manufacturers of such light aircraft—including Pipistrel, Aero Electric Aircraft Corp. and Airbus Group—exhibited on the ground, the lack of suitable certification rules in the U.S. and Europe seems to be impeding progress. Airbus exhibited their E-Fan “Plus,” painted in the colors of the American flag! But instead of the second rear seat, in its place was a small two-stroke avgas engine (Solo Aircraft 2625) with 41-liter capacity, a series produced in Germany for sailplanes, to drive a range-extending generator, doubling the airplane’s flight endurance to around two hours plus a 30-minute reserve. E-Fan Plus would use its batteries and electric motors during takeoff and landing and the gasoline power plant during cruise. Following Air Venture at Oshkosh, the prototype returned to Saint-Sulpice-de-Royan, France, for further testing during the autumn of 2016.11

In November, Didier Esteyne traveled to Oslo, where he joined the Norwegian Airbus engineer Nils-Harald Hansen during the Zero Conference at Youngstorget to present the E-Fan 1:1 to KetilSolvik-Olsen, Minister of Transport and Communications; Dag Falk-Petersen, CEO of Avinor; John Eirik Laupsa, Secretary General of Norwegian Air Sports Federation; and Marius Holm, the head of Zero Conference. This fitted into Norway’s dynamic of adopting electric transportation in all its forms: land, air and water. The northernmost county of Finnmark may become a giant testing ground for Norwegian and international green flights.

In March 2017 Airbus abruptly dropped its involvement in the all-electric E-Fan, while announcing that it would continue to pursue the development of a 90-seater short-haul hybrid called the E-Fan X. This was part of an austerity plan which would make over one thousand employees redundant, including closure of their R&D site in Suresnes and Pau. The new factory in the south of France would be used to explore how to introduce future electric-hybrid production concepts, eventually including commercial airliners. Several partners, including Daher-Socata and electric motor maker Siemens, are involved in the project.

On Thursday, March 23, 2017, taking off from the Dinslaken Schwarze Heide airfield, Walter Extra piloted the 330LE to a top speed of around 337.50 kph (209.7 mph) over a distance of three kilometers (1.86mi)—13.48 kph (8.38 mph) faster than the previous record, set by Bill Yates in 2013. The World Air Sports Federation (FAI) officially recognized the record flight in the category “Electric airplanes with a take-off weight less than 1,000 kilograms.” In a slightly modified configuration with an overall weight exceeding one metric ton, test pilot Walter Kampsmann then flew 330LE to a speed of 342.86 kph (213 mph). On March 24, 2017, the Extra 330LE became the world’s first electric aircraft to tow a glider into the sky. Walter Extra took a type LS8-neo glider up to a height of 600 meters (2,000 ft.) in only 76 seconds. Frank Anton, head of eAircraft at the Siemens venture capital unit next47, commented, “Just six such propulsion units would be sufficient to power a typical 19-seat hybrid-electric airplane. By 2030, we expect to see the first planes carrying up to 100 passengers and having a range of about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles).”12

In early April 2017, with more than 600 exhibitors from 35 countries, 33,000 visitors and 600 journalists from around the world, the AERO Friedrichshafen in Germany saw further developments in the e-flight-expo, organized in cooperation with Flying Pages GmbH. The “e” in e-flight stood for ecological, electrical, and evolutionary to promote ecological sustainability and progress in aviation. Companies such as Extra, Siemens, Pipistrel, Yuneec, Alisport, Axter Aerospace, Geiger Engineering and many more, as well as institutions such as GAMA or the University of Ulm, presented the latest e- and he-airplane developments. One day prior to the start, on Tuesday, and on closing day on Saturday, several aircraft with electric propulsion systems flew their rounds silently in the sky over the fairgrounds—Fabian Gabor in the Magnus eFusion, Walter Extra in Extra 300 Elektro, Edouard Maitre in the Volta Elektro Helicopter, Len Schumann in the e-Genius, and Jochen Polsz in the Antares 23E. At an oil spill exercise in the afternoon on Lake Constance, firefighters demonstrated an operation with drones. In addition, there were e-flight lectures about the history and development of electric flight.

Electric air shows still have a way to go compared to aviation meetings of a century ago. For example, in August 1909, a mere 6 years after the Wright Brothers took off, La Grande Semaine d’Aviation de la Champagne (The Great Champagne Aviation Week) was held near Reims in France. Almost all of the prominent aviators of the time took part. No fewer than 38 airplanes were entered for the event, though in the end only 23 actually flew, representing nine different types. Eighty-seven flights of more than 5 kilometers (3 mi) were made.

2017: Visitors to AERO at Friedrichshafen saw the Siemens-engined Extra and E-Fusion fly past in silence (Messe Friedrichshafen/AERO Friedrichshafen).

From left, Tine Tomažič, Frank Anton of Siemens and Ivo Boscarol, key players in Pipistrel’s development (Pipistrel).

From June 5 to 9, 2017, the AIAA Transformational Electric Flight Workshop & Expo was held at the Sheraton Denver Downtown Hotel. It brought together speakers and attendees from industry, government and academia worldwide. One of its features was the 4th Joint Transformative Vertical Flight Workshop. Among the speakers was Paul Eremenko, CTO of Airbus, who described the CityAirbus that the French original equipment manufacturer (OEM) is currently researching. It will be a four-seat, all-electric vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft, and the “flagship” of the Airbus urban mobility division. The first flight of CityAirbus is expected to occur in 2018. It is currently being developed at the E-Aircraft Systems House, which is capable of testing power systems in excess of 20 megawatts. Eremenko said the ultimate goal, though, is the development of a completely new, single-aisle aircraft, powered by hybrid electric propulsion technology. In pursuit of that goal, Airbus continues to work on the E-Fan X. “For the first time since the jet age of passenger aviation … we’re really thinking about opening up the design trade space, beyond the tube and wings configurations,” Eremenko said. “Hybrid propulsion enables us to think about distributed thrusters, creating a blown wing effect that could allow shrinking the wing area, or using differential thrust to control the yaw of the aircraft, reducing the vertical tail surface, or boundary level ingestion to re-ingest the wake at the tail of the airplane, cutting the overall drag by up to 10%.”13

One way ahead for Airbus’s E-Fan X single-aisle airliner project was to take the BAe 146/Avro RJ regional jet airliner, nicknamed the Whisperjet for its quiet operation, and modify its 2-megawatt-class turbogenerator and batteries powering electric propulsors replacing one or two of the aircraft’s four turbofans. But as the system matures and is demonstrated to be safe and, presumably, as battery costs come down, provisions will be made toward replacing a second turbine with another 2MW motor. If sanctioned, the aircraft would fly by 2020.

In September 2017, René Meier and his colleagues organized the world’s first electric aircraft fly-in at Grenchen airport in Switzerland (Markus Jegerlehner).

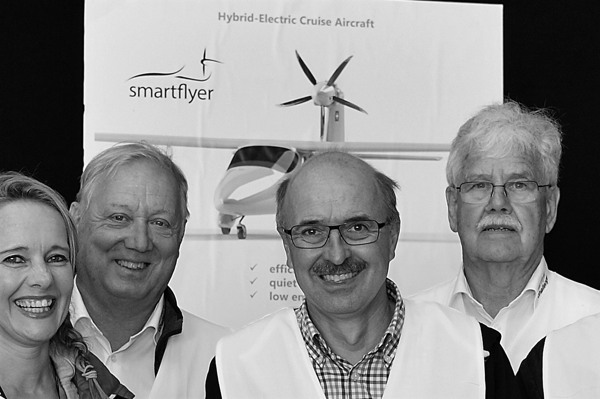

On the weekend of September 9–10, 2017, a team led by René Meier, ex-colonel of the Swiss Air Force, organized the SmartFlyer Challenge, Europe’s 1st Fly-In (as opposed to Air Show) for electric-powered aircraft at Grenchen Regional Airport (LSZG), Switzerland, with both static and air displays of electric and hybrid-electric powered aircraft. The required electricity was produced by the airport itself, because every hangar roof is equipped with solar cells. The airport itself can also afford the three charging stations, each with 200 amps required for the Smartflyer Challenge. Grenchen Airport produces around 340,000 kWh of solar power per month. No fewer than seventeen electric airplanes and component manufacturers exhibited their products. In order to show the full range of electric mobility, electric bicycles and motorcycles were exhibited, Tesla was represented, and there was an 18-ton full-body truck on the ground. In addition to stands where developers and companies from Switzerland, Germany, France, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Norway presented their products, a number of lectures and presentations were given in the existing training rooms of Grenchen Flying School: speakers included Dr. Frank Anton; Jean-Luc Charron, who reported on the state of the French project, where an electric airplane was integrated into the normal club operation; and Tine Tomažič, together with his colleague Paolo Romagnolli, presented the Pipstrel Alpha Electro aircraft. Lange Aviation presented the Antares E2 fuel cell aircraft. While the old established aircraft manufacturers were noticeably absent, this was made up for by the forward-looking start-ups.

On Friday, September 8, the first electric aircraft to land at Grenchen airfield was the Magnus e-Genius piloted by Frank Anton coming over from Biel. But because of rain, Saturday became a static show, and spectators could walk around the passenger octocopter, Whisper, developed by Yves Pearcy of the French company Electric Aircraft Concept. Also present was the SmartFlyer being developed by two Swiss Airline pilots, Rolf Stuber and Daniel Wenger. The four-seater hybrid-powered aircraft with a 12-m (40-ft) wingspan has been developed in Grenchen; its potential range is 4 hours/800 km, and its 46 kg Siemens e-engine is linked to a two-cylinder piston engine. The project with a budget of 1.2 million Swiss francs over a period of five years is supported by 72 percent of the sustainability fund of the Federal Office of Civil Aviation.

Rain might have completely stopped play, but on Sunday afternoon, between the black clouds above the Jura and the blue sky above the Seeland, a perfect weather window opened. Over twelve e-airplanes, from ultralights to sailplanes to aerobatics, were able to take off and give more than three dozen demonstration flights, a world first.14 Aviatrix Cornelia Ruppert from Wald, Switzerland, flew the family company’s new Archaeopteryx, called the Elec’teryx, a self-launch, single-seat high-wing pod-and-boom microlift glider.15

2017: Roger Ruppert of Switzerland, engineer of the e-assisted Archaeopteryx sailplane; his aviatrix wife Cornelia has made 126 hours flying the Electric Archaeopteryx (courtesy Ruppert).

In 2017, a first: three electric airplanes in formation. Frank Anton pilots the Magnus e-Fusion (foreground), followed by the D-14 Phoenix motorglider, and the e-Genius. To the left, see the other e-aircraft parked below (photograph courtesy Jean-Marie Urlacher).