There seems to be no stopping the proliferation of multicopter drones in every walk of life and they come in all shapes and sizes, be they UAVs, MAVs or PAVs.

In contrast to the less-than-one-hour duration and short distance of a drone race, others have still been working on the eternal UAV, first developed by Paul MacCready. In April 2014, Google acquired Titan Aerospace, which had developed catapult-launch drones with 200-ft. (60-m) wingspans called Solara 50 and Solara 60, capable of flying at a reported altitude of 20 km for impressive periods of over 5 years. By early 2016, Google was developing the Skybender, their latest solar-powered UAV, in a large warehouse in New Mexico. The goal was to use millimeter wave radio transmissions to bring Internet speeds of up to 40 times faster than those provided by 4G LTE systems.

The Autonomous Systems Lab of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ), in cooperation with industry partners, developed their AtlantikSolar. It weighs just 6.8 kg (15 lb.) and has a 5-m (16-ft.) wingspan. On July 14, 2015, the AtlantikSolar was hand-launched at the Rafz RC-model club. Despite winds of up to 60 kph (37 mph) and thunderstorm clouds in the last two hours of the flight, the UAV flew continuously for 81 hours, breaking the world endurance record for unmanned aerial vehicles under 50 kg (110 lb.). Given its name, the next flight was planned to be 5,000 km (3000 mi) across the Atlantic Ocean, on a preprogrammed route from Boston to Lisbon over seven days. That flight will follow a preparatory 12-hour flight from Belem to the Caxiuana research station in the middle of the Amazon rain forest, covering about 400 km (250 mi.) on solar power alone.

ETH’s team leader Philipp Oettershagen, a Caltech Fulbright scholar and UAS engineer, predicts squadrons of these mini-planes deployed to save human lives. In June 2015, the AtlantikSolar participated in the EU-funded search and rescue project ICARUS in Portugal, where it tested out victim detection flights over water for the first time. From October 21 to 31, 2015, AtlantikSolar had the chance to assist directly in the first real-life (i.e., outside of research projects) disaster support mission. Requested by SIPAM (Brazilian Amazon Protection System, part of the Brazilian Ministry of Defense), AtlantikSolar was tasked to perform aerial sensing and mapping around the site of a disaster—a sunken ship that involved over 4,400 dead cattle and 750 tons of oil spill—that had happened 2 weeks before. In June 2017, glaciologists from ETH Zurich used the 6-kg (13.2-pound) AtlantikSolar to monitor glaciers in Greenland; after 13 hours in the air, fog rolled in and that drone had to be retrieved. To date, AtlantikSolar has made flights up to 81 hours, and the plan is still to make an autonomous flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

After the flights of Paul MacCready in the Solar Challenger and Didier Esteyne in Airbus E-Fan, it was inevitable that a drone would cross the 35 km (21.7 mi) of the English Channel. This was achieved on a sunny February 16, 2016, by commercial drone mapping/photography firm Ocuair, based in Westbury, Wiltshire, UK. A custom airframe was designed by UK-based UAV manufacturer Vulcan, efficient T-motors and blades provided the lift, while Optipower provided two huge 22-amp hour batteries, Jeti provided the secure and robust control links, and Nottingham Scientific Ltd. provided the GPS tracking devices. The quadcopter dubbed Enduro1 was piloted by Richard Gill from an accompanying rigid inflatable boat staying within 500 m (1,640 ft.) of the drone. Morning takeoff was from Wissant beach between Boulogne and Calais. The flight was going well as they passed the point of no return, 17 km, from which the distance to the UK was shorter than returning to the original launch position, so there was no escape plan. At 23 km, Enduro1 suddenly lurched to the left and the pilot had to disable the GPS guidance and take manual control of the flight for the final 20 minutes. Flying without GPS assistance was extremely challenging. After a flight of 72 minutes, the drone landed on Shakespeare Beach in Dover, southeast England, mission accomplished.

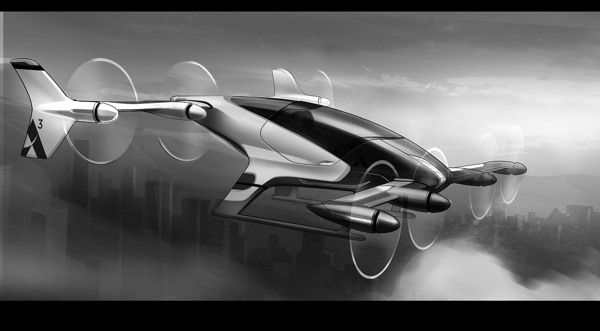

To improve the breed of commercial drones, in April, Airbus Group SE teamed up with Local Motors to launch the Caro Drone Challenge Contest. The starting design of this competition was Airbus’s Quadcruiser hybrid concept, combining the VTOL and hovering capabilities of the well-known quadcopter design with the speed and cruise efficiency of a fixed-wing aircraft by using an additional pusher motor. There were 425 entries. At a ceremony held in July 2016 during the Farnborough International Airshow, five winners were announced: Alexey Medvedev from Omsk in Russia; Harvest Zhang from Mountain View in California; Dominik Felix Finger from Aachen in Germany; Finn Yonkers from North Kingstown, Rhode Island; and Frederic Le Sciellour from Pont De L’Arn in France. They shared an overall prize pool of well over U.S. $100,000. As a next step Airbus and Local Motors have been building a demonstrator version of the winning design concept, again through an open collaboration involving the community, including potential customers and end-users.

On July 21, 2016, Facebook announced that it had flown Aquila, its solar-powered drone, for more than 90 minutes in a test over Arizona, calling it a “big milestone” for its connectivity plans to build drones, satellites and lasers to deliver the Internet to everyone, whether living in a world city or in a remote area of a developing country. The video was watched by almost 3 million viewers. Ascenta, headed by Andy Cox, is a small drone maker in Bridgewater, Somerset, England. Facebook acquired the team behind Ascenta in March 2014 for just under $20 million. The Aquila was dismantled and taken in pieces to Arizona. There, it was reassembled for its first flight. The Aquila drone has the wingspan of a 737, but can run on the power of three hair dryers. It is designed to fly for up to three months at a time, only consuming 5,000 watts of energy at cruising speed.1 Ten months later, Aquila completed its second flight, during which it flew for an hour and 46 minutes. This time around, Facebook added “hundreds of sensors” to gather additional data; modified the auto-pilot software; installed a horizontal propeller stopping mechanism to support a successful landing; and added “spoilers” to the wings, which increase drag and reduce lift during the landing approach. It is being checked by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board. Airbus and Facebook have now agreed to partner on high-altitude pseudo-satellite development.

Also in July 2016, the Farnborough Air Show in England hosted the very first edition of its UK Drone Show. For the first time, drones had their own dedicated space at the show. There were drone-related activities on the public days, including a drone air display and the UK Drone Racing Masters Championship (see Appendix A).

It was inevitable that fuel cells would be incorporated into drone technology. In June 2015, Michel M. Bitton and a team at EnergyOr Technologies in Montreal flew their fuel-cell multicopter H2Quad 1000 inside a hangar at half a meter above the floor for 3 hours, 43 minutes and 48 seconds. Two years later, EnergyOr shipped the first H2Quad 1000 to the French Air Force’s Centre d’ Expertise Aérienne Militaire (CEAM) in Mont de Marsan, France.

On the afternoon of January 19, 2016, the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) completed a test flight above Oban airport in Scotland of a Raptor E1 drone, built and designed by Trias Gkikopoulos of Raptor UAS and using Cella’s hydrogen-based power system. The complete system, a Cella gas generator along with a fuel cell supplied and integrated by Arcola Energy, is considerably lighter than the lithium-ion battery it replaced. Although the flight lasted only 10 minutes at a cruising altitude of 260 ft. (80 m), the drone had a potential autonomy of 2 hours. Larger versions of this system will have three times the energy of a lithium-ion battery of the same weight. Cella is also working on aerospace systems with its partner Airbus-Safran Launchers, now ArianeGroup.

In late summer 2016, Protonex, a subsidiary of Burnaby-based fuel-cell developer Ballard Power Systems, delivered its proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells to Insitu, a subsidiary of U.S. aerospace giant Boeing that produces military- and industrial-grade, long-endurance, fixed-wing drones such as the ScanEagle. Insitu has stated that it hopes to roll out a commercial, liquefied hydrogen fuel-cell version of its ScanEagle drone by 2017. At the same time, Intelligent Energy of Loughborough, England, took a standard DJI Matrice 100 drone and, by reequipping it with a fuel cell, extended its flight range from 20 minutes to over an hour. Demonstrations were at the InterDrone conference, which ran September 7–9, 2016, at the Paris Hotel in Las Vegas. In China, MMC introduced its carbon-fiber HyDrone 1800 with a flight endurance of 4 hours, or 50+ hours when combined with MMC tethered technology.

Proliferation of UAVs for military and security purposes has continued. The CIA has been flying unarmed drones over Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia since 2000. It began to fly armed drones after the September 11, 2001, attacks. Some were used during the air war against the Taliban in late 2001. But on February 4, 2002, the CIA’s Eagle Program first used an unmanned Predator drone armed with Hellfire missiles in a targeted killing. The strike was in Paktia province in Afghanistan, near the city of Khost. The intended target was Osama bin Laden, or at least someone in the CIA had thought so. As of 2008, the USAF has employed 5,331 UAVs, which is twice the number of its manned planes. Of these, the Predators have been the most effective. The overall success of the Predator missions is apparent because from June 2005 to June 2006 alone, Predators carried out 2,073 successful missions in 242 separate raids. While Predator is remotely operated via satellites from more than 7,500 miles away, the Global Hawk operates virtually autonomously. Once the user pushes a button, alerting the UAV to take off, the only interaction between ground and the UAV is directional instructions via GPS. Global Hawks have the ability to take off from San Francisco, fly across the U.S., and map out the entire state of Maine before having to return. In February 2013, it was reported that UAVs were used by at least 50 countries, several of which have made their own, including Iran, Israel and China. The U.S. military inventory now comprises more than 12,000 ground robots and 7,000 UAVs.

Off-the-shelf drones began to be used by Islamic State or Daish in 2014. At first they used them to film propaganda videos from the air. Then they became scouts. A drone video of a Syrian military base was released shortly before the base was hit by multiple suicide bombings that targeted its weak spots, suggesting that the drone had been sent in on a surveillance mission. In October 2016, the Islamic State carried out a drone strike of their own. A UAV, its explosive device inside disguised as a battery, reportedly exploded after being shot down by Kurdish forces in Iraq, killing two fighters.

Sky Sapience HoverMast-100, a compact, mobile, electric-powered, intelligence-gathering tethered flying machine, has been developed since 2010 by Brigadier-General (Ret.) Gabriel Shachor, with Shy Cohen and Roonen Keidar at Yokne’am Illit, northern Israel. Weighing 10 kg (22 lb.), it can carry almost its own weight in equipment, such as radar systems or sensors, while tethered to a small vehicle like a car or truck. The cable also carries power generated by an electric power supply unit at the base station to the machine at a height of 50 meters, attained in 10 seconds, and the electric power supply unit offers unlimited operation time. Data collected by the payloads is transmitted through a wide-band communication link connected between the HoverMast-100 aerial system and the ground station. The first HoverMast-100 was ordered by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) for its Ground Forces Command in August 2012, and the system was delivered in September 2013. One is reminded of the tethered PKZ1 rotorcraft developed by Stephan von Petróczy in 1917 (see Chapter Three).

During the Great Solar Eclipse of August 21, 2017, researchers from Oklahoma State University and the University of Nebraska used low-flying drones to track changes in atmosphere; the flight was part of the broader Collaboration Leading Operational Unmanned Development for Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics (CLOUD MAP). Later that month, Hurricane Harvey was recorded as the wettest tropical cyclone on record in the contiguous United States. The resulting floods inundated hundreds of thousands of homes, particularly in Texas, displaced more than 30,000 people, and prompted more than 17,000 rescues. While it was dissipating, the U.S. National Hurricane Center began monitoring a tropical storm over the west coast of Africa. Further surveillance of the storm led the NHC to classify it as Tropical Storm Irma on August 30. As the storm picked up speed, Irma took a deadlier turn. As of September 5, Irma was upgraded to a Category 5 hurricane with wind speeds gusting at 175 mph. It goes down in record books as the strongest storm in the Atlantic Ocean.

On September 8, an earthquake of 8.1 on the Richter scale hit Mexico in which over 90 people died. Although weather satellites and NASA were able to show the size and the movement of the two hurricanes, in the aftermath, to establish the extent of the damage, the FAA issued permits to commercial drone operators to assist in a number of different functions that expedited the recovery process. These included identifying victims, delivering rescue ropes and life jackets in areas that were too dangerous for ground-based rescuers to venture into, and observing the damage to buildings, roads and bridges, and power lines; this work was done by small quadcopters to the military-grade catapult-launched Insitu ScanEagle, as well as 4G LTE tethered drones to provide wireless service to areas without network coverage by acting as temporary cell towers.

In October, following the nation’s deadliest mass shooting on the Las Vegas Strip (59 deaths and 489 injured), it was suggested that a weapon-armed security drone could have taken off in two minutes and fired an incendiary device into the lone gunman’s hotel room on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay Hotel.

The first use of a drone for filming the aerial footage in a major film was in 2012 for Skyfall, directed by Sam Mendes. Skyfall has a spectacular opening sequence, shot by the Flying-Cam 3.0 SARAH Unmanned Aircraft System, in which James Bond 007 uses a motorbike to chase a terrorist across the rooftop of the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul. The high-speed aerial footage captured by the drone in that scene made a buzz in Hollywood, contributing to the movement that saw, a couple of years later, 6 aerial filming companies get the first 333 FAA exemptions for closed-set filming.

In 2015, a British thriller film, Eye in the Sky, highlighted the ethical challenges of drone warfare. It is just one of over twenty recent feature films which feature combat drones. In February 2016, the Hollywood Reporter wrote, “There has been no shortage of films dealing with drones over the last few years … audiences have recently had the occasion to explore a form of modern warfare whose true repercussions are yet to be fully understood, let alone divulged to the general public.”2

In October 2016, the American video production company Stratus Productions bolted a 1,000-watt LED light bar to the underside of a Freefly Alta 8 octocopter drone. Although it has an autonomy of only 10 minutes, the drone was able to light up an entire city block or forest.

Drones have played an increasingly large role in wildlife preservation and filmmaking in recent years. In 2011, a team of filmmakers flew a German-built Microdrone md4–1000 quadcopter above the Masai Mara region of the Serengeti to capture video of all sorts of African wildlife. Researchers in Kenya, meanwhile, have begun using unmanned aerial drones to monitor areas susceptible to rhino poaching. In November 2016, Northrop Grumman engineers and San Diego Zoo Global scientists traveled to the Arctic, where they used a UAV to track polar bear movements over thousands of miles while measuring the ice pack that is critical to the species’ survival. The UAV was an all-electric, fixed-wing aircraft with a 14-foot wingspan and a custom fuselage for the accommodation of several optical sensors. It was also equipped with multi-terrain landing gear and environmental packaging for the rough Arctic environment, where temperatures regularly drop below zero degrees Fahrenheit.

Rather than drones which are used to look down, and spy, and bomb, and race, others are becoming an art form to be looked up at. A visual display was created in 2012 by Saatchi & Saatchi’s award-winning Jonathan Santana and Xander Smith with Marshmallow Laser Feast of London. “Meet Your Creator: Quadrotor Show” was a live theatrical performance / kinetic light sculpture with quadrotor drones, LEDs, motorized mirrors and moving head spotlights dancing to music by OneOhtrix. Elsewhere, Horst Hörtner and his 15-strong team at ArsElectronica Futurlab GmbH in Linz, Austria, created a similar choreography of “spaxels” (space pixels), luminous colored drones which are remote-controlled to perform a ballet in the night sky. The first ballet took place at home in 2012 when a formation of 50 drones took to the sky, thrilling festival goers in Linz and creating a media sensation worldwide. Spaxels® shows in London, Brisbane and Dubai not only delighted crowds on site; they created a sensation in social networks too. With Intel’s interest expressed in a display of coordinated aerial artistry in conjunction with a new Intel campaign, the company supported the technical R&D that aimed to make the flight more secure. The challenge was for four pilots to launch 100 drones and deploy them aloft to paint 3D images and messages to the accompaniment of a live orchestra for maximum impact. “Drone 100,” performed in the sky in November 2015 above Flugplatz Ahrenlohe in Tornesch, near Hamburg, Germany, earned a new world record title for the most Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) airborne simultaneously. The Spaxels moved in sync to the beginning of the Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, even spelling out the word “INTEL.”

Raffaello D’Andrea, a Canadian/Italian/Swiss engineer, artist, and entrepreneur working with Weixuan Zhang and Mark W. Mueller at the Department for Dynamic Systems and Control at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland, developed the Moonspinner, a drone that can fly with only one propeller. In May 2016 it featured in a Cirque du Soleil show in Broadway, where a fleet of drones disguised as lampshades danced around the human performers as part of their Paramour Show. The Moonspinner features no additional actuators or aerodynamic surfaces. It cannot hover like a standard multicopter, but can be launched like a Frisbee.

The Vivid Festival in Sydney provided the ideal setting for the public debut of the Drone 100 project. On five evenings, June 8–12, 2016, spectators in Australia witnessed a performance custom-tailored to the occasion and with musical accompaniment by the Sydney Youth Orchestra. The brilliantly illuminated silhouette of Sydney’s world-famous Opera House, the city’s architectural landmark on Bennelong Point, lit up the sky above the harbor.

Meanwhile, James Alexander Stark, R&D Imagineer Principal at Walt Disney Imagineering, with Clifford Wong and Robert Scott Trowbridge, had obtained U.S. patent 9102406 B2 for “Controlling unmanned aerial vehicles as a flock to synchronize flight in aerial displays.” For the 2016 Christmas season, Disney and Intel launched drone light shows at Florida’s Walt Disney World Resort, where no fewer than 300 super light Intel Shooting Star drones, made from Styrofoam and plastic, equipped with LED lights and weighing only 280 g (10 oz), created over four billion different color combinations, programmed and controlled from just one computer. Among the images: Christmas trees and angels.

In December 2016, Intel improved its Guinness World Record when, from a football field in Krailling, Bavaria, Germany, it simultaneously launched 500 Shooting Star drones to give a flawless ballet in the night sky, finishing by displaying the number “500” in the air. The entire swarm was controlled by one pilot and one PC. Each quadcopter’s propellers are also protected by covered cages—all features designed to ensure the drone is safe to fly, is splash-proof and can fly in light rain.3

The Shooting Star fleet’s next venue came in February during the halftime break at the 51st Super Bowl, the American football championship game between the New England Patriots and the Atlanta Falcons. Lady Gaga’s singing was accompanied by the 300-strong fleet, recently over from Disney World, forming an image in red, white and blue of the American flag. Marking the first time drones had been used as part of a live television broadcast, the display was watched by an estimated 111.3 million people.

Was there a limit to the number of drones in the sky simultaneously? On the night of February 11, 2017, one thousand colored EHang drones flew up into the sky, alongside the landmark Canton Tower in Guangzhou, southern China, to celebrate the Lantern Festival, the last day of the Chinese New Year holiday. During a 15-minute performance, with an orchestra playing below, controlled by one computer, the thousand drones flew in six different formations of Chinese characters including “Blessing,” “Lantern Festival,” and the map of China. At the 2018 Winter Olympics, Intel again raised the record for the number of skyborne drones with no fewer than 1,218 Shooting Star drones flying in sync to create huge light-up images of Olympic sports and the iconic Olympic rings in the skies over Pyeongchang.

It is interesting to note that, to date, the greatest number of radio-controlled model aircraft airborne simultaneously is 179, achieved by on July 16, 2016, above Furey Field in Malvern, Ohio. This was organized by Howard Kaler of Plainfield, Illinois, in conjunction with the Flite Fest East family community. The previous record was 99 planes. Registrations for the event had been closed at 300 planes, with an additional 100 participants turned down. Although they did not collide with each other, unlike drones, these model aircraft were certainly not flying in formation. The same may be said for the average number of airplanes criss-crossing around the globe at any given time: over 16,000.4

On May 11, 2017, at the Xponential event held at the Kay Bailey Hutchinson Convention Center in Dallas, 10 quadcopters performed a synchronized routine on a fake bride, flashing LED lights that can create over 4 billion color combinations. On August 9, 2017, to celebrate Singapore’s 52nd birthday celebration National Day Parade, a 300-strong drone display animated the night sky above Marina Bay with an outline of Singapore Island, a heart with a crescent and five stars, the NDP 2017 logo, a hashtag, the Merlion, children and an arrow shape, logos and even a map of the country. One month later, in Los Angeles, people looking skyward over Dodger Stadium witnessed an illuminated display celebrating a comic book superhero. But it was not the Bat Signal sending out a distress call for Batman—it was a fleet of 300 lit-up drones performing choreographed maneuvers to spell out Wonder Woman’s trademark “W” symbol. The dynamic light show was produced by Warner Bros. in partnership with Intel’s drone team, for the U.S. release of the film Wonder Woman on Blu-ray.

Drones will soon be flying around indoors at home. Back in September 2015, Tessie Hartjes and Lex Hoefsloot founded Blue Jay at Eindhoven University of Technology and Fontys University of Applied Sciences, southeast Netherlands. Their goal was to develop a domesticated drone which could navigate indoors using a Wi-Fi system with special lights produced in collaboration with Philips. These lights, mounted on the ceiling, each emit light at a different frequency. A camera on top the Blue Jay can then distinguish between the different frequencies. A laser that constantly measures the distance to the ground determines how high the Blue Jay is flying. R&D was carried out by a multidisciplinary team of 19 top students. In April 2016 the Blue Jay team set up the world’s first drone café, featuring Blue Jays that could take orders and serve them. The drone café was part of the three-day Dream & Dare Festival marking the 60th anniversary of Eindhoven University’s foundation.

Drones are also entering the classroom. Krishna Vedati, formerly with AT&T Interactive’s Consumer Division, and his team at tynker.com in San Francisco create apps and curricula that teach children the basics of coding using games and real-world gadgets. Their downloads are used by some 60,000 schools in the USA (30 million kids). Tynker recently launched a new project—teaching coding through drone lessons. Schools typically buy between six and 12 drones via Tynker’s partnership with drone maker Parrot and can then download Tynker’s free set of drone lessons. Children learn to make drones do back-flips, as well as more complex ideas such as drones working together as a team.

In December 2015 Twitter patented a photo-sharing camera drone that is controlled by tweets; thus the selfie married the drone with the AirSelfie, as invented by Dylan Tx Zhou. This is a pocket-sized flying camera that connected with smartphones to enable HD photos and videos of the owner and his friends. Its turbo fan propellers could thrust up to 20 meters (65 ft.) in altitude for a duration of three minutes. In October 2016 Amazon obtained a patent for a pocket-sized, voice-controlled camera drone that can be used to help police in chases, aid firefighters in tackling blazes, and even find lost children. In December 2016, Samsung, a maker of smartphones, cameras, and even a 360-degree VR-friendly camera, patented a completely circular drone, with a bulge at the bottom holding what seems to be a small camera.

For Christmas 2016, Casey Owen Neistat, an American YouTube personality, filmmaker, and blogger, conceived of an idea to release a video, Human Flying Drone, of himself using a giant drone to snowboard around Finland. Sponsored by Samsung, the 10-ft. (3-m)-diameter hexadecacopter was fitted with sixteen 31-inch (78-cm) carbon-fiber propellers powered by 16 individual electric motors. Neistat, wearing a Santa Claus costume for the feat, ski-jored (slalomed to and fro while towed by his drone) up and down the snowy slopes and at one point rose up into the sky. The YouTube video was watched by millions of viewers worldwide.

A remote-controlled flying-toys company has come up with possibly the best toy idea ever—drone toys of famous Star Wars ships such as Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon and the rebels’ X-Wing starfighter. Propel, which already sells a wide range of model helicopters as well as consumer UAVs, showcased its new Stars Wars Battling Quad drones at the Star Wars Celebrations convention in London, which took place over the weekend of July 15–17, 2016, at London’s ExCeL Centre. Propel has shown off impressive miniature drone versions of famous Star Wars spaceships that can be used to play real airborne dogfights at speeds above 35 mph (60 kph) and engage friends and family in exciting multiplayer laser battles.

In 2016, Goitein Bezalel of Powerup Toys in Miami teamed up with Parrot to develop a paper drone. The “pilot,” wearing a smartphone with a head-mounted display, can see what the drone sees and can control it with intuitive movements of his head. Once folded, the paper plane supports a frame that includes control electronics, two motors, a battery, and a tiny camera. There is also a microSD slot for recording the flights.

According to ABI Research, the drone industry is going to be worth $8.4 billion by 2019. This is not only from hardware sales, but mainly from the applications and services where most growth is expected.

From the fall of 2016, Professor David Lentink, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, and his team have benefited from a wind tunnel based on various measurement systems acquired with support from the Air Force, Navy, Army, Human Frontiers Science Program, and Stanford Bio-X program. The Stanford team’s goal is to observe how tiny birds fly, then transfer the same skills to flying robots or drones. The tunnel is a 2-meter-long chamber that can blast gusts of up to 50 meters per second. The tunnel is the first of its kind able to create turbulence, using computer-controlled wind vanes.

Researchers at the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) Robotics and the Laboratory of Intelligent Systems (LIS) at the École Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne, Switzerland, have bio-mimicked the intricate folding patterns of rove beetle wings to develop a drone that opens up and takes to the skies in less than a second with a couple of swift movements, and can be carried in a backpack to remote and dangerous areas. The result is a drone that when folded up has only 43 percent of the wingspan and 26 percent of the surface area of when it is in operational mode, where its wings measure 200 × 500 × 16 mm (7.87 × 19 × 0.62 in). LIS’s previous work includes a drone that uses its wings to crawl on land like a sea turtle and a grasshopper-inspired robot that can jump 27 times its body size.

Alongside such an approach, engineers at Airbus are looking at how future airplane shapes may mimic birds and dolphins. The most noticeable aspect of this approach is in the fuselage, which, instead of being wrapped in opaque steel, is composed of a web-like network of structural material that looks a bit like a skeleton.

On November 3, 2014, Nixie, a small camera-equipped drone that can be worn as a wrist band, competing against more than 500 other participants, won Intel’s Make It Wearable competition, thus securing $500,000 in seed funding to develop Nixie into a product. It can be activated to unfold into a quadcopter, fly in one of its pre-programmed modes to take photos or a video, and then return to the user. Nixie, based in Palo Alto, California, was founded by Jelena Jovanovic, a Stanford physics researcher, and Christoph Kohstall, holder of a Ph.D. in experimental physics and former manager at Google, as well as technical program manager at OpenROV. Their goal is to develop their drone into the next generation of point-and-shoot cameras.

Laurent Eschenauer and Dimitri Arendt of Grâce-Hollogne, Belgium, have developed the Fleye (Flying Eye), a personal autonomous robot drone with a unique spherical design the size of a football, where all moving parts are fully shielded. Fleye has a powerful on-board computer, similar to the latest smartphones. It is a dual-core ARM A9, with hardware accelerated video encoding, two GPUs, 512MB of RAM, and it runs Linux. It also supports the popular Computer Vision library OpenCV. This means that Fleye can be programmed to execute missions autonomously, reacting to what it sees in its environment. On the functional side the Fleye’s design takes a cue from industrial and defense UAVs, relying on a “ducted fan.” Unlike most drones on the market that have multiple open rotors, the Fleye’s lift is generated by a single shielded propeller with four control vanes providing directional control. The drone sports an array of sensors including an accelerometer, gyroscope, altimeter, GPS, sonar, optical flow, and a magnetometer, so right out of the box, the Fleye can track you, take 360-degree images, or fly other preplanned autonomous missions at the tap of an icon. Users need only switch on, open the app, choose select what they want Fleye to do, then toss it into the air, like a football.5

At Drone World Expo in November 2016, AeroVironment, still in the game after three decades, unveiled the VTOL Quantix, an industrial-strength fixed-wing drone for agriculture, energy, and transportation industries, among others. Quantix can map 40 acres (16 hectares) in about 45 minutes (its overall flight time is approximately an hour). About the size of their Raven, Quantix weighs 5 lbs. (2.3 kg) with a wingspan of 3.2 feet (1 m). But unlike the Raven, which is launched airplane-like, horizontally, Quantix will initially use four propellers to take off vertically like a consumer-brand quadcopter. Upon reaching cruising altitude of about 400 feet (120 m), Quantix can flip over and fly horizontally like an airplane at speeds up to 45 mph (70 kph). Landing will also be conducted vertically. Operators can fly Quantix easily using one-touch planning and launch via a dedicated Android tablet device. The AeroVironment Decision Support System (AV DSS™) is a full-service, cloud-based data analytics system.

Roman Luciani and Antoine Tournet of Toulouse, France, have established Airvada to develop the Diodon, an inflatable drone which, thanks to its patented inflatable structure, is at the same time easy to transport, waterproof, and rugged because of the flexible structure. In a patented system, CO2 cartridges are used to inflate them in only 30 seconds, while packing away takes just 60. Thanks to the independent inflatable chambers, the Diodon is extremely reliable; up to two chambers can burst without compromising the flight.

At the very beginning of this history, we noted Leonardo da Vinci observing bird flight, then in 1620 we came across the “gansa” super-geese towing Domingo Gonzales into the sky and up to the moon. Three centuries later, Etienne Edmond Oehmichen published his work Nos maîtres les oiseaux, étude sur le vol animal et la récupération de l’énergiedans les fluides (Our masters, the birds, a study on animal flight and recovering energy in fluids). Now, one hundred years later, flying fauna still inspire more than ever.6

Bay Zoltan Nonprofit Ltd., a state-owned applied research institute of Logistics and Production Engineering in Budapest, Hungary, has developed a flying tricopter called Flike, its Li-Po batteries giving a potential 30–40 minute flight. The Flike achieved its first manned flight on March 7, 2015, at Miskolc Airfield in northeast Hungary, staying airborne for over a minute with a takeoff weight of 463 lb. (210 kg) and landing safely. The lift is generated by six rotors grouped in counter-rotating pairs on three axes, equally located around a circle. The rotation speed of individual rotors can be adjusted, and an onboard computer takes care of the craft’s stability.7

Experimentally there is no limit to the number of copter-engines. To prove the point, in 2015 a British inventor created a “super drone” with 54 propellers, enough to keep a human airborne. The machine, dubbed “The Swarm,” could only remain in the air for 10 minutes on a single battery charge and appeared to climb to a height of around 15 feet (7 m.). Two years later, a similar DIY one-off was YouTubed in the Swedish forest, where an engineer went up and down for eight minutes in his polycopter.

On August 29, 2016, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, following work with NASA, announced their regulations for the use of small drones, freeing organizations from having to request special permission from the federal government for any commercial drone endeavor—a waiver process that often took months. Under the new commercial-drone rules, operators must keep their drones within visual line of sight—that is, the person flying the drone must be able to see it with the naked eye—and can fly only during the day, though twilight flying is permitted if the drone has anti-collision lights. Drones cannot fly over people who are not directly participating in the operation or go higher than 400 feet above the ground. The maximum speed is 100 mph. Drones can carry packages as long as the combined weight of the drone and the load is less than 55 pounds. Dispensing with the requirement to have a pilot’s license to fly a commercial drone, the regulations allow people over age 16 to take an aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved facility and pass a background check to qualify for a remote pilot certificate. Real estate, aerial photography, construction and other industries that want to use drones for basic functions, such as taking a few photos or videos of a property, probably will benefit the most because their plans align more closely with the regulations, industry experts said. Although the new rules allow drones to carry loads, the visual line-of-sight rule and the weight restriction will keep more ambitious companies with plans for long-distance travel, such as Amazon and Google, from making significant deliveries that way. More than 3,000 businesses had already received a government exemption to fly, but given the estimation that there will be seven million small drones in operation by 2020, including 2.6 million aircraft for commercial use, NASA and the FAA will be further refining regulations.

The FAA launched its online drone-registration program in December 2016. It required all pilots, even hobbyists, to register their robots by February 19. It generally cost $5 per registration, but the FAA waived this cost through January 20. Information in the registry will be public record. In the program’s first two days, the FAA collected 45,000 registrations.

In this dronomanicial adventure, growth of PAVS has been exponential.

In 2010, Alexander Zosel of Karlsruhe, Germany, teamed up with former Siemens IT expert Stephan Wolf and electrical engineer Thomas Senkel to design and build what they called a Volocopter, basically a scaled-up child’s drone to carry a pilot. Between 2011 and 2014, coordinated by Professur Heinrich H Bülthoff of the Max Planck Institute für biologische Kybernetik, six research institutions across Europe studied the feasibility of the small commuter helicopters, with a $4.7 million grant from the European government: the University of Liverpool, the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, the Karlsruher Institut für Technologie, and the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft und Raumfahrt. The optimal solution would consist in creating a personal air transport system (PATS) that can overcome the environmental and financial costs.

On October 21, 2011, following elaborate simulations at Stuttgart University, the e-volo team had built the prototype 16-motor, all-electric VC1 “Volocopter,” which Thomas Senkel test-flew for 90 seconds. The video of the flight achieved 1 million clicks on YouTube within a few days. Following the flight, the decision was made to decommission the VC1 and to merely use it as an exhibit. In 2012 a patent was issued, and the e-volo won the Lindbergh Innovation Prize for that year. From January 2013, the innovative concept of their electronic VTOL aircraft was able to so convince the German Federal Ministry of Transport that it resolved upon a trialing scheme spanning a period of several years for the creation of a new aviation class for the Volocopter. The DULV (The German Ultralight Association) was commissioned with drafting a manufacturing specification, work regulations and the training scheme for the future pilots in cooperation with e-volo. Following further refinements, the 2 kW VC-2 (or VC200), now fitted with 18 Czech-built MGM electric motors and nine batteries, was demonstrated unmanned in November 2013 at an enclosed arena in Karlsruhe, Germany. The following month, e-volo managed via the Seedmatch online crowd-funding platform to attract funding of €1,200,000.00 within just three days, a new European crowd-funding record. The first €500,000 of this sum was subscribed within just 2 hours and 35 minutes.

By August 2015, sophisticated intercommunicating electronic components had been manufactured and tested providing automatic height and position adjustment, enabling the pilot to take his hands off the joystick control, with the VC200 able to carry up to 200 kg including the pilot. That December, within the scope of the “SolutionsCOP21—Celebrate the Champions Night” at the Grand Palais on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, e-volo received Climate Champion COP 21, the award for their Volocopter.

In February 2016, the German Ultralight Flight Association granted e-volo a provisional certificate for its VC200 as an ultralight aircraft (certificate number D-MYVC). On March 30, 2016, Alexander Zosel was the pilot for the VC200’s first three-minute manned flight over the dm-arena in Bruchsal, near Karlsruhe. Called The White Lady on account of its livery, it proudly carried the registration D-MYVC. Further encouraged, the Volocopter test flight program could continue. In June 2016, manned flights at speeds of up to 70 kph maximum and at higher altitudes were carried out at a special flight test area in Bavaria. At 50 kph, an autonomy of 27 km (17 mi) was achieved. Test flights within the third testing phase aim to validate the system at higher altitudes and in the full speed range of the VC200 up to 100 kph. A full aircraft emergency parachute was fitted, as well as multiple redundancy in all critical components such as propellers, motors, power source, electronics, flight control, displays, and highly reliable communication network between devices through a meshed polymer optic fiber network (“fly-by-light”).

2016: Volocopter founders Alexander Zosel (right) and Stephan Wolf (left) in front of the VC200 multicopter (Volocopter).

2016: The Volocopter VC200 200–5 watt power unit (Volocopter).

In January, Volocopter moved into its new headquarters in Bruchsal, bringing together the design office and the hangar/airfield at one site. At the 2017 AERO in Friedrichshafen in April, e-volo unveiled their two-seater Volocopter 2X optionally designed as manned taxis, remote-controlled and autonomous flights. With entirely new components, the 2X has been developed for approval as an ultralight aircraft and should receive multicopter-type certification that shall be created under the new German UL category in 2018, enabling anyone with a Sport Pilot License (SPL) for multicopter to fly it. For the future, e-volo is striving to obtain a commercial registration that allows for transportation of passengers as commercial taxi flights. The development of a 4-seater Volocopter with international approval (EASA/FAA) is one of the next planned steps. The e-volo team planned test flights of the 2X during the summer of 2017. In June, the Dubai government’s Roads and Transport Authority (RTA) signed an agreement with e-volo regarding the regular test mode of autonomous air taxis in the Emirate. On September 26, 2017, watched by Dubai Crown Prince Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed, Volocopter A6-RTA made its first unmanned field test, near Jumeirah Beach. Trials between voloports will go on for five years. Primary reasons for choosing the Volocopter included the stringent German and international safety standards. Dubai plans to handle 25 percent of all of its passenger travel using autonomous transportation by as early as 2030. The following month, Volocopter agreed to a finance deal of over 25 million euros with the automobile firm Daimler from Stuttgart, the technology investor Lukasz Gadowski from Berlin, and further investors. Using this fresh capital, Volocopter could speed up the introduction process of the Volocopter serial model.

In late 2017, Brian Krzanich, the chief executive of Intel, became the first official passenger to ride in an air taxi when an 18-prop copter from Intel’s partner, the German company Volocopter, lofted him within the confines of the company’s hangar near Munich. In 2018, at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, Krzanich indicated that from now on Volocopter and Intel would be working closely in the field of electric air taxis.

Another airplane type is the gyrocopter that uses an unpowered rotor in autorotation to develop lift, and an engine-powered propeller, similar to that of a fixed-wing aircraft, to provide thrust. The technology goes back to the 1920s, but it was not until June 2015 that an electric autogyro took to the skies. For two years, backed by Lower Saxony Aviation, AutoGyro GmbH of Hildesheim, Germany, had been refitting one of their two-seater Cavalon gas gyros with a Bosch SMG 180 (80kW / 200Nm), also used on the FIAT 500e electric Smart Car, and to help drive the rear wheels on the Peugeot 3008 Diesel HYbrid4. This was linked to an INVCON 2.3 electronic controller and a 16.2 Ah Li-Po battery. The Cavalon is only 4.7 meters (15.2 feet) long, 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) wide, and 2.8 meters (9.2 feet) high, topped by its 8.4 meter (27.5 feet) rotor. The 45-minute maiden flight took place from Hildesheim airfield on June 24, 2015.8

Sometimes concept aircraft remain concept; other times they are realized. NASA’s Puffin VTOL concept has been taken up by a start-up called Lilium based in Gilching, Germany, in the form of a 100 percent electric short-haul private jet that may at last fulfill the promise of the flying car. “Lilium” comes from linking the name of 19th-century German gliding pioneer Otto Lilienthal with the lily flower and the lithium battery. The company was founded in 2015 by a quartet of engineers and doctoral students from the Technical University of Munich and nurtured in a European Space Agency-funded business incubator in Bavaria. “Our goal is to develop an aircraft for use in everyday life,” says one of Lilium’s founders, CEO Daniel Wiegand. As the Lilium team saw it, the problem with personal aviation is airports, which are expensive to operate and utilize, and usually sit well away from city centers, negating their use as commuter hubs. Lilium designed an airplane that could take off and land vertically and did not need the complex and expensive infrastructure of an airport. It would require an open space of just 225 m2 (2,400 ft2)—about the size of a typical back yard—to take off and land. The Lilium Jet would cruise as far as 500 km (310 mi) at a very brisk 400 kph (248 mph), and reach an altitude of 3 km (9,900 ft). Overnight recharging could use a standard household outlet. In 2015 and 2016 Wiegand filed for patents using a VTOL pivotal aerofoil system. At the end of 2016, €10 million of finance for Lilium came from Niklas Zennstrom, Skype’s cofounder and former CEO, through his venture capital firm Atomico. Lilium said it intended to use the new money to expand its existing team of 35 aviation specialists and product engineers. As head of recruiting, they appointed Meggy Sailer, former head of talent EMEA at Tesla, who oversaw Tesla’s growth from 200 to 13,000 employees worldwide. In August 2017, Lilium received an additional $90 million worth of new investment from China’s Tencent and several other investors including Obvious Ventures, co-founded by Ev Williams, who also helped create and run Twitter. This made it one of the best-funded electric aircraft projects in the world. Lilium also hired former Airbus and Rolls-Royce engineer Dirk Gebser to manage production and Dr. Remo Gerber as chief commercial officer. Due to Lilium’s technology of moving from hover flight to forward flight, longer distances and higher speeds would give the German company the edge on other existing electric airplanes.

In mid–April 2017, Lilium completed a series of short test flights with a pilotless full-scale prototype, announcing plans to run the Eagle, its first two-seater vehicle test, in 2019, with commercialization of a five-seater following in 2025. The short film of its trials, posted on the Internet, was watched by 10 million internauts. Lilium has been in discussion with the European Aviation Safety Agency (AESA), which has already carried out work for the insertion of drones.

2018: Lilium Aviation, based in Gilching, Germany, has received €100 million for the development of their electric VTOL. From left to right: Daniel Wiegand, Matthias Meiner, Sebastian Born, and Patrick Nathen beside the two-seater Eagle prototype in Bavaria (Lilium Aviation).

In August 2016, Airbus announced that it was developing “an autonomous flying vehicle platform for individual passenger and cargo transport,” the first test flight of which was slated for late 2017. The project name was Vahana, a name that stems from the Sanskrit word meaning “that which carries” (Sanskrit: वाहन). R&D by A3, Airbus’s innovation outpost in California’s Silicon Valley, had been in progress since February. The project executive is Rodin Lyasoff. In 2002, Lyasoff was on a team that built the first aerobatic helicopter, the X-Cell 60, at MIT (where he also earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees in aeronautics and astronautics). He spent several years at Athena Technologies designing flight software for a number of vehicles including the AAI Shadow, Alenia Sky-X, and the NASA Mars Flyer. Subsequently, Lyasoff led flight software at Zee.Aero. He then went to Airware, where he built the world’s first hardware and software platform for commercial UAVs. Among his patents are “Variable geometry lift fan mechanism” (2015), a vertical takeoff and landing aircraft with rotors that provide vertical and horizontal thrust. During forward motion, the vertical lift system is inactive. A lift fan mechanism positions the fan blades of the aircraft in a collapsed configuration when the vertical lift system is inactive and positions the fan blades. In his LinkedIn entry, Lyasoff writes, “I love making improbable vehicles fly. I love building and growing engineering teams, and guiding product development to enhance customer amazement.” Initial tests in January 2018 were tethered while Airbus hopes to have the Vahana certified and ready for use by 2020.

The Vahana passenger drone will rely on obstacle detection and avoidance systems similar to those already seen in vehicles like the Mercedes-Benz E-Class. For this, Sanjiv Signh and his team at Near Earth Autonomy in Pittsburgh have developed a sensor system called Peregrine, named after the falcon. The system, mounted under the fuselage, contains lidar, Light Detection and Ranging, which uses lasers to measure air data parameters such as true airspeed, angle of attack, and outside air temperature; the craft also features inertial measurement, GPS sensors, and all kinds of processing power. When the aircraft is at an altitude lower than 65 feet, it laser-scans the ground in three dimensions, looking for objects bigger than 12 inches across, to determine whether the landing spot is clear and safe. If it does spot an impediment, it will suggest an alternative LZ and feed that back to Vahana’s flight control computer. The company has designed the self-contained Peregrine sensor system as an easy retrofit to existing aircraft. A3 planned to start flight tests of a prototype in November 2017. The flight tests were conducted from Pendleton Unmanned Aerial Systems Range in Oregon, where the company recently occupied a new 9,600-square-foot hangar, specifically configured to support the trials. Boeing’s HorizonX division has also invested in Near Earth Autonomy’s Peregrine system.

2017: A3, Airbus’s innovation outpost in California’s Silicon Valley, is developing the Vahana, a name that stems from the Sanskrit word meaning “that which carries” (Sanskrit: वाहन) (courtesy Airbus).

To work through this and allied vehicle efforts, the Skyways project involves Airbus Helicopters Deutschland GmbH and the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore. Using a cross-flow fan patent developed by Sebastian Moresat Rotorcraft, development is underway of a multi-passenger VTOL, called CityAirbus. In October 2017, the CityAirbus team led by Marius Bebesel thoroughly checked the individual performance of the ducted propellers as well as the integration of the full-scale propulsion unit with two propellers, electric 100 KW Siemens motors, and all electrical systems. The full-scale demonstrator will be tested on the ground initially. In the first half of 2018 the development team expects to reach the “power on” milestone, meaning that all motors and electric systems will be switched on for the first time. The first flight is scheduled for the end of 2018. In the beginning, the test aircraft will be remotely piloted; later on, a test pilot will be on board.

CityAirbus and Vahana will then be tested on the campus of the National University of Singapore, and so help shape the regulatory framework for unmanned aircraft operations in that country. In the first phase, multiple drones will deliver parcels across the Singaporean university campus using defined aerial corridors. If successful, a second phase will extend deliveries to ships in the Port of Singapore. Airbus Helicopters has developed the “zenAirCity” business and mobility concept in which quiet, electrically powered aircraft such as Vahana and CityAirbus are integrated into the transport infrastructure of a megacity. The vision is a range of products and services from ride-booking and -sharing apps, through flying taxis and luggage services, to cybersecurity to protect the system. Although the prototype would be piloted, subsequent versions will be autonomous.9 However, Neva Aerospace, a European consortium driving the development of key technologies for flying cars, such as their AirQuadOne, believes such fully autonomous flights remain a long way off. Another retro-style flying car concept has been inspired by a 1920s automobile design, complete with maroon and black coloring: the Hover Coupé.

Likewise, the Cormorant has been developed by Urban Aeronautics of Yavne, Israel, led by former Boeing airplane engineer Rafi Yoeli, also a reserve officer in the Israeli Air Force. Trials of the UA passenger-carrying Cormorant took place late in 2016 in Megiddo. The company claims that the Cormorant can fly between buildings and below power lines, attain speeds up to 115 mph (185 kph), stay aloft for an hour and carry up to 1,100 pounds. At present its power source is gas, which fuels a standard helicopter engine, with lift from two fans buried inside the fuselage, called a Fancraft. Of 47 U.S. and worldwide patents that have been applied for, 39 have already been granted. The civilian version, called the CityHawk (a play on Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, where the Wright Brothers made their first flights), would be built by Metro Skyways Ltd., a subsidiary of Urban Aeronautics. Although Israel is also working on boosting the energy density of batteries, Urban Aeronautics is also investigating running it on liquid hydrogen fuel and also 700-bar compressed hydrogen … again, this plan depends on waiting for the infrastructure and technology to mature. It may even employ a system in which hydrogen is fed directly into a specially designed turboshaft engine, eliminating the need for fuel cells or electric motors.

In March 2017, at the International Motor Show in Palexpo, Geneva, Switzerland, Airbus and Italdesign-Giugiaro of Moncalieri near Turin premiered the Pop.Up, a 5-by-4.4-m autonomous passenger octocopter that can be docked with wheels to turn into a 2.6-m battery-electric carbon-fiber auto. Once passengers reach their destination, the air and ground modules with the capsule autonomously return to dedicated recharge stations to wait for their next customers. A fleet of Pop.Ups would be artificially intelligently managed to interact with trains and hyperloops to navigate around tomorrow’s megacities. The Pop.Up is expected to take 7 to 10 years for realization.

The combination of an aircraft with a road vehicle has also been explored by Richard Glassock. Since 2008, Glassock, a Queensland University of Technology–based mechanical engineer, has specialized in the hybrid potential of UAVs made from off-the-shelf model aircraft components. In 2010, he proposed that another advantage of hybrid-electric aircraft would be their use for short-haul skydiving flights. Following a spell in Hungary, Glassock relocated to Nottingham University, UK. In 2017, he developed a highly innovative project whereby the range of an electric aircraft would be extended by a 50kW electrical generation power unit in the form of a gasoline-engined motorcycle slung underneath it, which could then be detached after landing and used on the roads. Glassock unveiled his RExLite and RExMoto in September 2017 at the International Conference on Innovation in European Aeronautics Research in Warsaw, Poland. The engine, generator, chassis and drive structure are claimed to have a novel layout and the whole unit weighs no more than 125 kg. Retractable wheels ensure that RExMoto can fit beneath the aircraft’s fuselage or under a wing while minimizing drag in flight mode.

Another entrant came from Stephen S. Burns and Alan J. Arkus at Workhorse Group Inc. of Loveland, Ohio. Their planned SureFly quadcopter’s fuselage and two fixed contra-rotating propellers on each of the four arms are made of carbon fiber–reinforced plastic (CFRP). The craft has a backup battery to drive the electric motors in the event of engine failure and a ballistic parachute that safely brings down the craft if needed. Formerly known as AMP Electric Vehicles, Workhorse has combined its experience in carbon-fiber drones and electric vehicles to design a two-seater with a 70-mile range. Early models will be pilot-operated. The goal is to introduce future autonomous models able to carry payloads of up to 181 kg. SureFly was unveiled at the Paris Air Show, then at EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh, then at CES 2018 in Las Vegas. Test flights are scheduled in 2018 for a Federal Aviation Administration certification in late 2019.

David Mayman and Nelson Tyler of Jetpack Aviation in Van Nuys, California, having developed the world’s first jet turbine backpack, JB-9 and JB-10, progressed to an electric version capable of flying under battery power for five minutes.

In early 2017, Uber, whose rideshare app is available in over 66 countries and 507 cities worldwide, hired Mark Moore, who had worked as director of aviation for NASA for thirty years, including the PAV Puffin and the Maxwell X57. In late April, Moore ran their Elevate Network summit in Dallas, bringing together experts in Vertical Electric Take Off and Landing (VETOL). It announced that it would be teaming up with the governments of Dallas–Fort Worth and Dubai to test out its flying taxi network. The company would be working with Dallas real estate development firm Hillwood Properties to plan vertiports, sites where the aircraft would pick up and drop off passengers. To develop the vehicles, Bell Helicopter of Fort Worth would team up Embraer (of Melbourne, Florida), Pipistrel and Aurora Flight Sciences with their XV-24A X-plane program currently underway to develop airworthy vehicles. ChargePoint would develop charging stations. Uber also hired Celina Mikolajczak, a senior battery engineer who previously was in charge of battery cell quality and materials analysis while at Tesla. Uber planned to have its technology ready for demonstration by the World Expo in Dubai in 2020, with a fleet of 50 VETOLs to follow. Uber investigated the potential of Sydney and Melbourne as potential candidates for Elevate. Australia’s Civil Aviation and Safety Authority confirmed it was ready to “meet challenges” involved in regulating air space for new flying vehicles. However, Australians will have to wait until at least 2023 to take their everyday commuters to the skies, and will have human pilots for the first five to 10 years while enough data is collected to convince regulators that sky taxis are safe.

At the CES in January 2018, Bell unveiled the cabin design of its hybrid-electric FCX-001 concept BellAirTaxi, with its rotorless anti-torque tail boom, extensive use of glass in the fuselage, gull-wing doors, and sustainable composite construction. It will have rotor blades capable of morphing to suit the need of the pilot. It would also be equipped to harvest, store, and distribute energy. The pilot would control the aircraft using the same augmented reality that the passengers can use to check the news, share a document, or watch a movie, among other things. At the show, visitors enjoyed simulated VR rides in the cockpit.

At the same summit, Mooney Aircraft announced partnership with Carter Aviation to produce another 4–6 seater VETOL, using Carter’s patented Slowed Rotor Compound (SR/C) technology for efficient hover and efficient cruise at 175 mph. The General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA) hosted the final day of the Summit along with the second training session about the U.S. government’s Part 23/CS-23 rule rewrite for the design of small airplanes, which would enable such projects to be successful. Michael Hirschberg, executive director of the American Helicopter Society (AHS), considers that the next 50 years of vertical flight will see electric air taxis become as normal as automatic elevators.

Mike Tolkin, a techno-businessman behind such innovations as IMAXShift, a high-tech indoor cycling studio in which scenes are projected onto an extra-large screen, and Rooms.com, a home design website that offers virtual tours of designer rooms, is running for the Democratic nomination for mayor of New York. As part of his forward-thinking campaign, Tolkin has created the Smart Cities concept, in which electric Skybuses will enable faster and more efficient inter-borough transit.

Passenger Drone, led by Paul Delco and based in Zurich, has developed a 16 e-engined air taxi, which makes use of adaptive flight control, wireless fiber-optic internal communications, field-oriented motor control and encrypted communication channels. Although there is autonomous mode using LTE (4G) network, the pilot can take over at any time with touch-flight control or fly-by-wire joystick. Following a maiden flight in July 2017, Passenger Drone has started the certification process with the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration and the European Aviation Safety Agency in early 2018, and aims to make the drone commercially available in 2019. One thinks back to the sci-fictionalist Alberto Robida, who described a similar system back in 1893 (see Chapter One), although set in the 1950s.

The Russian approach to PAV is based on the Bartini Effect discovered by the Italian-Soviet aircraft designer Robert Bartin (aka Barone Rosso): the increase in thrust created by mounting co-axial counter-rotating thrusters within a nacelle. Since 2015, the startup Bartini, with its motto “Weird to think of—in 1985. Easy to hop on—in 2020,” has been working on two VTOL variants: a 2-seater and 4-seater, with the intention of an air taxi service. Bartini, based at the Skolkovo Technopark, on the western outskirts of Moscow, has been funded by the company’s eight founders, part of the Blockchain.aero consortium. The Blockchain consortium is the first crypto-currency platform for mass urban aviation, whose task is to automate the charging, maintenance and parking of flying cars. The Russian consortium plans to deploy urban community-driven aviation systems for passengers and city managers in 2020. First test flights are aimed for Dubai, Singapore or Sydney in 2018. Flight scheduling will be done via a mobile application and will offer different levels of service from fast to entertainment flight.

Indeed, in September 2017, Boeing put up U.S. $2 million in prize money to encourage bright ideas around building and designing an easy-to-use personal flying device. The GoFly prize followed a similar blueprint to the XPrize competitions and the Hyperloop Global Challenge, in that it tasks anyone who was willing and able to come up with technological concepts that would move humanity forward in a big way. The deadline for the first phase of the GoFly competition was April 4, 2018.

On June 5, 2017, Caihong (Rainbow), a solar UAV developed by Shi Wen and a team at the China Academy of Aerospace Aerodynamics (CAAA), a subsidiary of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, made its first test flight to a height of 65,000 ft. Measuring 14 m long with a 45 m wingspan, its eight e-prop configuration recalling Helios, Caihong is designed to cruise at a speed of 150–200 kph and stay airborne for months at a time—a sort of Zephyr.

Higher still, in June 2017 Airbus launched the all-electric EUTELSAT 172B from Kourou, French Guiana, by Ariane 5, to provide enhanced telecommunications, in-flight broadband and broadcast services for the Asia-Pacific region. The 172B combines electric power of 13 kW with a launch mass of only around 3,500 kg, thanks to the latest EOR (Electric Orbit Raising) version of Airbus’s highly reliable Eurostar E3000 platform. It uses full electric propulsion for initial orbit raising and all on-station maneuvers, with Xenon gas ejected at high speed using only electric power supplied by solar cells.

The Japanese Int-Ball spheroid camera drone, manufactured by JEM entirely using 3D printing, weighs 1 kg (2.2 lbs.), has a diameter of 15 cm, and has 12 propellers. In June 2017, it was delivered to the Japanese module Kibo on the International Space Station (ISS). Although the ISS flies at an altitude of between 330 and 435 km (205 and 270 mi), by July, remote-controlled from Earth by the JAXA Tsukuba Space Center, Int-Ball had been used on board to save crew members time by snapping pictures of experiments.

ARDN Technology, based in Kazan in southwest Russia, has developed the SKYF mega-drone capable of carrying a 400-pound (181-kg) payload and of flying for up to eight hours. Measuring 5.2 meters (17 feet) by 2.2 meters (7.2 feet), the SKYF has a maximum flight speed of 70 kph (43.5 miles per hour) at a maximum height of 3,000 meters (9,843 feet) and has a positional accuracy of 30 centimeters (11.8 inches). The drone uses its gasoline-powered engines for its two primary lift props, and uses all four sets of twin props with electric motors to help stabilize and steer it. Although it’s fairly large in size, it can fold down so that two can fit into a 20-foot (6-meter) cargo container. In addition, it requires 10 minutes of setup before it can fly. ARDN has arranged for test flights at the Kurkachi Airfield (Kurkachi village, Republic of Tatarstan). They are planning to commence ARDN implementation in the Republic of Tatarstan, Krasnodar Region, Voronezh and Tambov Regions, and other subjects of the Russian Federation. Almost in parallel, Boeing’s Horizon X is working on a similar heavy-lifter cargo drone with a planned carrying capacity of 400 lbs. for 15 minutes at 60 mph.

Although development is running parallel, there is one type of PAV which, once landed, can take to the roads thanks to its wheelbase. Flying cars have their own history.