Although it is only recently that hybrid-electric flying cars are being developed, the flying car has a sci-fi history going back over 160 years.

In Andrew Jackson Davis’s The Penetralia: Being Harmonial Answers to Important Questions, published in 1857 by Bela Marsh of Boston, the 30-year-old American clairvoyant predicted that “aerial cars will move through the sky from country to country.” Interestingly enough, in addition to his foretelling the coming of both the airplane and the car, he predicted prefabricated concrete buildings. In more detail, he predicted the “internal combustion engine, carriages and traveling saloons on country roads—sans horses, sans steam, sans any visible power, moving with greater speed and safety than at present. Carriages will be moved by a strange and beautiful and simple admixture of aqueous and atmospheric gases—so easily condensed, so simply ignited and so imparted by a machine somewhat resembling our engines as to be entirely concealed and manageable between the forward wheels of these land-locomotives.”

Forty years later, in Romania, Trajan Vuia, while still a young student, designed and built a scale model of a flying machine called a “winged automobile.” This was a three-wheeled velocipede on which was assembled a metal frame set vertically, at its upper part being clamped a wing, direction rudder, engine and propeller. He endured scoffing and ridicule mixed with envy when he went to France in 1902, after earning his doctor’s degree from the Budapest Polytechnic. Then on March 18, 1906, he tested his modular monoplane prototype Vuia I in Montesson, near Paris, taking off from an ordinary road, flying for 11 meters (36 feet) and landing. He later claimed a powered hop of 24 meters (79 feet).1

From 1910 to 1925, René Tampier built several different models of integrated roadable aircraft in his workshops at Boulogne-sur-Seine, a western suburb of Paris. On October 23, 1921, in Paris he drove his Avion-Automobile, and on November 7 he took to the air. This biplane, 3.7 m (12 ft.) tall and 7 meters (25 ft.) long, had four wheels conventionally placed, the front ones steerable and the rear axle equipped with a tiny differential. The fuselage and tail section remained rigid but the wings folded along each side. Cranks were used to fold them into a horizontal and longitudinal position. A second pair of rubber-tired wheels dropped into place. On the ground, the vehicle was powered by a small, 10-hp, four-cylinder, water-cooled, auxiliary gasoline engine, and in the air by a 300-bhp, Hispano-Suiza V-12 engine. Ten folding-wing units could fit where one regular aircraft was parked. Conversion took less than an hour, but problems emerged due to the vehicle’s height and bulkiness. Air speed was 112 mph (180 kph) and ground speed 15 mph (24 kph). Tampier tried unsuccessfully to interest the army in testing it for military uses.

René Tampier’s Avion-Automobile was the wonderment of Parisians in 1921.

Other than these two pioneers, the flying car remained in the realm of science fiction. In the 1920s and the 1930s, popular children’s author Oliver B. Capelle wrote a series of stories about Uncle Nat Denny, Buster and Sally, featuring their adventures with the Magic Flying Auto. These appeared in Children’s Playmate magazine. In the late 1940s, Texaco Oil included flying cars in advertisements for Sky Chief Brand gasoline. In the 1930s, both Victor Appleton and Victor Appleton II (pseudonyms) featured in their Tom Swift series of books for boys, Tom’s prolific vehicle intentions and exploits, including fantastic flying cars such as the Triphibian Atomicar.

In 1932, the Ambi-Budd plant in Berlin, which was making auto bodies for the Nazi Wehrmacht, produced an “Autoflugzeug” flying car for the Deutsche Luftfahrtausstellung (Aero Exhibition). With its overhead tricopter blades, the streamlined four-seat three-wheeler was given a registration to take to the road (IA-011032) and one to fly ((D-11032). A static exhibit, it never needed either, and was eventually destroyed during the wartime bombing of Berlin.

In 1945, designer Carl H. Renner at General Motors Special Body Development Studio painted his conception: the “Escacar” or “Unicycle Gyroscopic Rocket Car.” This was shortly before General Motors design chief Harley Earl, inspired by World War II aircraft, particularly the twin-tailed P-38 Lightning, gave the Detroit company’s latest automobiles tailfins, suggesting they might take to the air. Batman’s Batmobile, the first one to be extremely stylized, was originally a one-of-a-kind concept car, specifically a 1955 Lincoln Futura with its huge outward-canted tailfins.

The Gernsback Airmobile of 1955 was envisioned by Hugo S. Gernsback, editor-publisher from the 1930s of many popular pulp magazines on science fiction and other similar topics. His vehicle was a narrow, two-wheeled gyro car, powered by atomic-electrical energy that used telescopic, retractable stabilizers (wings) and had a retractable tail. A counter-gravitational field was to be created around or below the Airmobile, which meant that the pilot could levitate it at will.

Among the sci-fi stories written by James Blish, in the four-volume Cities in Flight series published by Avon between 1950 and 1962, one discovers an autonomously controlled flying taxi cab called “Tin Cabby”: “The cab came floating down out of the sky at the intersection and manoeuvred itself to rest at the curb next to them with a finicky precision. There was, of course, nobody in it; like everything else in the world requiring an IQ of less than 150, it was computer-controlled.… The cab was an egg-shaped bubble of light metals and plastics, painted with large red-and-white checkers, with a row of windows running all around it. Inside, there were two seats for four people, a speaker grille, and that was all: no controls and no instruments.…”

Blish was not alone. The Aircab appears in H. Beam Piper’s “Time Crime,” published by Astounding Science Fiction in 1955, whilst John Weston creates a Helicab, a taxi cab that flies using helicopter rotors, for his “Heli-Cab Hack,” published by Amazing Stories in 1950.

Robert Heinlein, in his The Star Beast, published by Charles Scribner & Sons in 1954, wrote: “They were half way home when a single flyer, hopping free in a copter harness, approached the little parade. The flier ignored the red warning light stabbing out from the police chief’s car and slanted straight down at the huge star beast. John Thomas thought that he recognized Betty’s slapdash style even before he could make out features; he was not mistaken. He caught her as she cut power.”

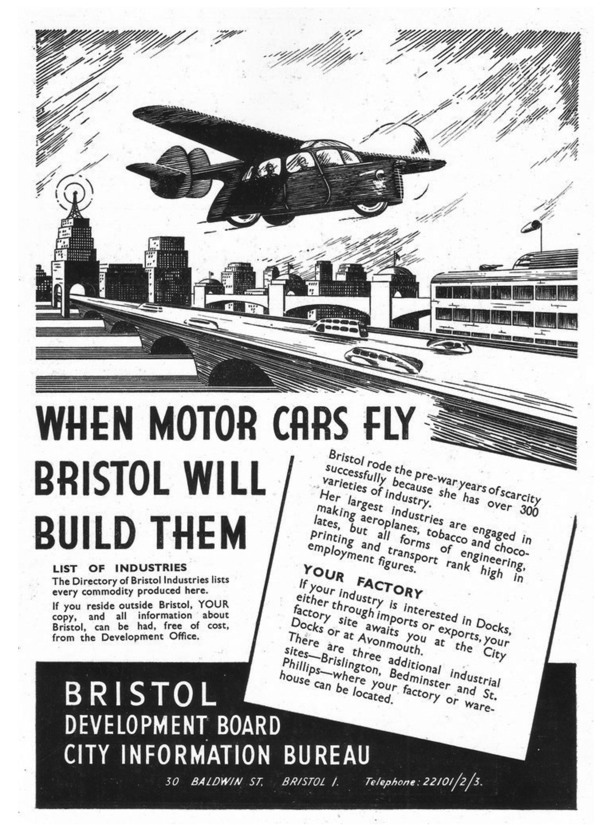

So was it sci-fi or fact when, in 1947, the Bristol Development Board in southwest England published an advertisement titled “When Motor Cars Fly, Bristol Will Build Them”? At that time the Bristol Aeroplane Company was indeed manufacturing an automobile, the Bristol 400, at their factory in Filton Aerodrome, where over 5,000 Bristol Beaufighter airplanes had been built for the war effort, but with an avgas engine. In fact, it was not until 1960 that Bristol indeed became involved with a flying car. The British government invited proposals from several companies for the design of a flying car for reconnaissance purposes. The wingless vehicle was to have a flight endurance of one hour at a speed of eighty miles per hour and have the land-borne cross-country performance of a Land Rover. The method of lifting had to be within the main dimensions of the vehicle. The first contender was Bristol-Siddeley, who proposed three powerful engines driving four gyro-controlled airjets which could raise the car up to 10,500 ft. in flight. Although a model was made, the full-scale craft was never built. Another proposal was put forward by Short Brothers & Harland. In the two-seater flying car, the road engine was a 90 hp Porsche, while a single 8,300-lb static-thrust Bristol-Siddeley would provide the nozzle thrust.

1947: When motor cars fly, Bristol will build them!

Was it therefore a coincidence that in 1964, English writer Ian Fleming, successful for his James Bond novels, wrote a children’s story called Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car, in which Commander Caractacus Pott pulls a switch that causes the vehicle to sprout wings and take flight over the stopped cars on the road? Commander Pott and his passengers fly to Goodwin Sands in the English Channel, where the family picnics, swims, and sleeps. The original Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang was an aero-engined motor car, built and raced at Brooklands by Count Louis Zborowski in the early 1920s, and maybe named after an early aeronautical engineer, Letitia Chitty.

In 1954, Scott C. Rethorst (Ph.D. at Caltech), President of the Vehicle Researching Corporation, South Pasadena, California, was issued U.S. Patent 2681773 for a roadable aircraft. Rethorst had also innovated a high-speed ship design, forerunner to the hovercraft. In 1964, Einar Einarsson of Farmingdale, New York, was awarded U.S. Patent 3090581 for a flying car. In his patent, Einarsson defines the purpose of the invention as to “provide a ground vehicle with propellers and wings, as well as wing flaps so that the vehicle may take off and fly in the air.” Although the bird-like design is impressive to look at, this winged vehicle never quite made it to production, even though an advertisement asked, “Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s the flying car. Your commute to work will never be the same! Beat your colleagues to work by simply flying over them!”

In the 1960s, American television viewers enjoyed the latest Hanna-Barbera animated sitcom, The Jetsons. George Jetson’s workweek is typical of his era: an hour a day, two days a week, and to do this he leaves his Skypad apartment in Orbit City, hops into his bubble-top green aerocar, and flies off to his job at Spacely Space Sprockets. En route, George’s children fly down to their schools, the Little Dipper Elementary and Orbit High School, and his wife Jane to the shopping center, each in their personal mini-drones. When George arrives, his aerocar folds itself up into a briefcase!

What we do not know is whether these vehicles benefited from silent electric propulsion. On the other hand, for his Fantastic Voyage II: Destination Brain, published by Spectra in 1987, Isaac Asimov creates a “Hushicopter”: “In the glow of the car’s headlights, Morrison made out a helicopter, its rotors turning slowly and its motor making only the slightest purr. It was one of the new kind, its sound waves suppressed, its smooth surface absorbing, rather than reflecting, radar beams. Its popular name was the “hushicopter.”… The automobile stopped and the headlights went out. There was still the faint purr and a few dim violet lights, hardly visible, marked the spot where the hushicopter sat.”

During the early 1960s, Moulton B. “Molt” Taylor of Longview, Washington, created a Lycoming-engined roadable airplane, the “Aerocar,” that was operated by radio station KISN in Portland, Oregon, for traffic updates. Piloted by “Scotty Wright,” it flew for “Operation Air Watch.” Painted white with red hearts, it had the letters KISN on the top and bottom of the wings.

Flying cars became serious with the arrival of Paul Sandner Moller, born in 1936 in Fruitvale, British Columbia, Canada. Gaining diplomas in aircraft maintenance and aeronautical engineering at PITA, Moller obtained an MA in engineering and a Ph.D. in aerodynamics at McGill University. From the mid–1960s and for the next fifty years, the lone Canadian began work on his Moller Skycar, a prototype personal VTOL aircraft, powered by four pairs of in-tandem Wankel rotary engines. But despite ground effect hovering, Moller never quite achieved free flight. With the advent of lithium batteries, in 2007 Moller announced his all-electric M200G Autovolantor, powered by Altair nano batteries.

By this time, Carl Dietrich and a team of graduates of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and graduates of the MIT Sloan School of Management had developed the Terrafugia flying car to make personal aviation more accessible. Dietrich was well qualified for the task. In 1996, as a summer intern at the NASA Ames Research Center, he had developed C-code to assist with the transportation logistics of the Space Station Biological research project. In 2000, at MIT, after winning four design competitions and founding a student group to develop advanced aerospace technologies, Dietrich was formally recognized by the Aero/Astro Department at MIT as the youngest of sixteen exceptional graduates under the age of 35. He received his BS, MS and Ph.D. from the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) shortly after receiving the prestigious Lemelson-MIT Student Prize for Innovation in 2006. In May of that year, with a team including Anna Mracek and Samuel Schweighart, Dietrich founded Terrafugia using the funds from his prize.

The Transition® was a Proof of Process for Terrafugia’s longer-term vision for the future of personal transportation. This was followed by a flying prototype in 2009 and a second-generation prototype in 2012. The latter, TF-X™, is a four-place fixed wing aircraft with electrical assist for vertical takeoff and landing. The vehicle will have a cruising speed of 200 mph (322 km/h), along with a 500-mile (805-km) flight range. Thrust from a 300 hp engine will be provided by a ducted fan. TF-X will have fold-out wings with twin electric motors attached to each end. In 2016, the FAA finally gave the go-ahead to certify the Terrafugia Transition. In July 2017, Chinese automaker Zhejiang Geely, based in Hong Kong, acquired Terrafugia. Geely, which already controlled Swedish car maker Volvo and Lynk & Co. and has a major stake in Malaysia’s Proton, had been looking to acquire the company since 2016. Units will be available by 2018.

2014 Terrafugia TF-X is a four-place fixed-wing aircraft with electrical assist for vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL). The vehicle has a cruising speed of 200 mph (322 km/h), along with a 500-mile (805 km) flight range. Thrust from a 300 hp engine will be provided by a ducted fan TF-X, and fold-out wings will have twin electric motors attached to each end (Terrafugia).

Some projects are staying with gasoline engines, but with the intent to convert once the 400 Wh/k energy density barrier has been broken. Slovakia’s roadable aircraft, the AeroMobil, has its own history. In the late 1980s, as students in Soviet-controlled Bratislava, Štefan Klein and Juraj Vaculik used to sit on the eastern bank of the Danube and stare longingly at Austria, the west and freedom. Vaculik, a drama student, found escapism in the theatre of the absurd. But Klein, an engineer then studying design, dreamt of a more practical solution, a flying car. He began this venture in his garage, at home in Nitra, Slovakia. In the early days, with the help of his family, he developed two prototypes—AeroMobil 1.0 during the early 1990s and AeroMobil 2.0 from 1995. But in 2010, things really took off when he joined forces with Juraj Vaculík to form the AeroMobil firm. In 2013, at the SAE Conference in Montreal, they unveiled the pre-prototype of AeroMobil 2.5, a sophisticated flying car, combining a luxury sports car and a light aircraft in a single vehicle. A year later, an experimental prototype of AeroMobil 3.0, its wings folding back like an insect, was developed under his lead with the team of 12 people, and presented at the Pioneers Festival in Vienna. On the road, AeroMobil is powered by a hybrid electric system. The generator is the same engine that powers the vehicle in the air; this in turn powers a pair of electric motors located in the front axle. In May 2015, the AeroMobil crashed at Nitra Airport during a test flight near Janíkovce (LZNI). The aircraft entered a spin and the ballistic parachute was deployed. The pilot, Stefan Klein, was sent to a hospital by ambulance complaining of back pain, but was later released. But the impact on the ground damaged the forward fuselage. Following a re-think and rebuild, on April 20, 2017, AeroMobil launched their 3.0 at the Top Marques Monaco, an exclusive supercar show, and announced that it would begin to take pre-orders for a “limited first edition” before the end of 2017.

Contrary to others, 51-year-old Pavel Brezina, an international para-motor builder and pilot based at Prerov-Bochor airport in the eastern Czech Republic, has created the hybrid-electric Gyrodrive. This is a mini-helicopter that can take to the road. Brezina’s firm, Nirvana Systems, buys gyroplane kits from a German firm and then assembles and equips them with a system allowing the pilot-driver to switch between a gasoline engine propelling the rotors and an electric engine that drives the wheels. The Gyrodrive is the only airplane certified for the road. After landing, the pilot only has to fix the main rotor blades along the axis of the GyroDrive and pull out a built-in license plate to transform it into a road vehicle. For his first trip, Brezina flew some 140 miles (230 km) west to an airport on the outskirts of Prague, then drove downtown to have a cup of coffee in the Czech capital’s central Wenceslas Square—and was stopped by the police on the way! Forty units are planned.

The Volkswagen hover car was a product of the “People’s Car Project” in China, which called upon customers to contribute design ideas for Volkswagen’s model of the future. The crowd-sourcing initiative debuted in China in 2011 and inspired 33 million website visitors to submit 119,000 ideas. The yoyo-shaped hovercraft would use electromagnetic levitation to float along its own grid above the regular road network; distance sensors would keep the craft from colliding with other vehicles. The disc-shaped pod would hold two people and could be controlled by a joystick that offered amazing maneuverability. The car could move both back-and-forth and side-to-side and could even spin on an axis. To top it off, the concept car produced zero emissions. Although a video was made, the hovercar was never built.

In March 2015, Umesh N. Gandhi and Taewoo Nam of Toyota Motor Engineering & Manufacturing North America, Inc., based in Erlanger, Kentucky, filed a patent called “Shape morphing fuselage for an aerocar.” This biomimicry approach describes molding the body in tensile skin to keep wings hidden in interior space. The wings would fold up inside a compartment and unfurl through a hatch. The propeller is shown on the back bumper of the patent illustrations. The vehicle would be driven using a power system that includes a battery pack, internal combustion engine turbine, fuel cell or other energy conversion device. The patent was awarded in September 2015.

It was inevitable that the Japanese would take part in the growing development of flying cars. Cartivator was founded in 2012 by Tsubasa Nakamura, 32, an automobile expert, from Mikawa in Aichi Prefecture, to develop Skydrive, a flying car measuring only 9.5 ft. (2.9 m) by 4.3 ft. (1.3 m), with a projected top flight speed of 100 km/h (62 mph), while traveling up to 10 m above the ground. By 2014, Nakamura had assembled a group of 20 engineers and designers ranging in age from 26 to 35 from across Japan’s auto industry, who donated their free time to work on the project. They also received some outside help from Masafumi Miwa, a drone expert and associate professor of mechanical engineering at Tokushima University, and Taizo Son, founder of GungHo Online Entertainment, a Japanese online video game developer. By August 2014, having conducted experiments at an abandoned elementary school in the mountains of the Aichi Prefecture, they had a ⅕-scale single-seat working model that combined electric drone and tricycle, one front wheel, two rear wheels, and a rotor in each of the four corners. Each rotor consisted of two propellers that allow the car to take off and land vertically. After presenting their prototype at an Ogaki Mini Maker Fair in Tokyo in 2014, the team set up a page on the Japanese crowd-funding website Zenmono, setting its fundraising goal at 1.8 million yen. By January 2015, it had raised almost 2.6 million yen (about $22,000 at the time). In May 2016, Japanese auto-making group Toyota announced its decision to give Cartivator 42.5 million yen (£274,000 or $392,642). Recently, the team has been working to reduce the weight of the vehicle, by replacing the 180 kg aluminum frame with a 100 kg frame made of carbon fiber-reinforced plastic. The team is also trying to improve the computer program that controls the rotation rate of the propellers. Cartivator plans to develop a manned prototype for a test flight by the end of 2018. To that end, it will work to develop technology to control propellers to stabilize the vehicle. The group hopes to commercialize the Skydrive by 2020 when Tokyo hosts the summer Olympic Games. The Cartivator team is aiming to run their vehicle on the track of the new National Stadium and fly it to the Olympic cauldron to light the flame at the opening ceremony. Mass production is planned for 2025, and by 2050 Cartivator could help make it possible for anyone to fly in the sky anytime.

In 2016, Elon Musk announced that his firm would develop a VTOL flying car version of their Tesla electric automobile, the Model F, which would be ready to ship in 2019. It would be built in collaboration with Volante Scherzo, an Italian roadable aircraft startup. After officially announcing the collaboration, Musk stated that the Model F would be able to reach a top speed of a staggering 482 km/h (300 mph) while in flight. But then on Friday, April 28, 2017, Elon Musk gave a forty-minute interview at the TED conference in Vancouver. Among his comments: “There is a challenge with flying cars in that they’ll be quite noisy, the wind force generated will be very high. If something’s flying over your head and there’s a whole bunch of flying cars going all over the place, that is not an anxiety-reducing situation. You’re thinking, ‘Did they service their hubcap, or is it going to come off and guillotine me?’” Musk had rejected the idea of flying cars as too dangerous, and switched over to his high-speed Hyperloop transportation venture.

Prolific aircraft designer 73-year-old Burt Rutan’s most recent design, BiPod, is a hybrid flying car or roadable aircraft. The twin-pod vehicle has a wingspan of 31 feet 10 inches (9.7 m); with the wings reconfigured (stowed between the pods), the car has a width of 7 feet 11 inches (2.4 m) and fits in a single-car garage. The design has two 450 cc four-cycle engines, one in each pod, which power a pair of generators that in turn power the electric motors used for propulsion. Lithium-ion batteries in the nose of each pod will provide power during takeoff and an emergency backup for landing. With a cruising speed of 100 miles per hour (160 km/h), Scaled Composites says the BiPod 367 would have a range of 760 miles (1,220 km). The prototype was built in a four-month period. Test hops have been performed with the prototype at Mojave Air and Space Port using propulsion from the wheels. The vehicle has been ground-tested up to 80 mph. No flight testing is planned.

Once the flying car marries the driverless car, then the four-wheeled drone becomes a reality. Of such quadcopter drones with wheels (car drones), drones with two functions, the most favored is the quadcopter with wheels or car-quadcopters: SY X25 Quadcopter Drone.

Among those investing in VTOL electric flying cars is billionaire Larry Page, co-founder of Google. In 2010, Page secretly funded a company called Zee.Aero, next to the GooglePlex headquarters in Mountain View, Silicon Valley, California. Zee.Aero was founded by Ilan Kroo, professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford and former NASA researcher at Ames. He recruited a surprising number of students and colleagues from both organizations to launch his startup. In order to improve on the energy front, Zee assembled an in-house team of electrochemists and physicists to build a battery research laboratory and develop custom cells with established manufacturers. Chen Li, former battery research scientist at GM, now became senior electrochemical engineer at Zee.Aero. The startup also hired other experts such as electrochemical engineer Patrick Herring, who holds a Ph.D. in condensed matter and materials physics from dual advisors at MIT and Harvard University. The battery management system was designed by former SpaceX electronics engineer Drew Eldeen. Zee also hired a Boeing 787 autopilot engineer to lead the design. According to patents, Zee.Aero, with its four-bladed propellers, could fit in a standard shopping center parking space. Zee.Aero now employs close to 150 people. Its operations have expanded to an airport hangar in Hollister, about a 70-minute drive south from Mountain View, where a pair of prototype aircraft have made regular test flights. The company also has a manufacturing facility on NASA’s Ames Research Center campus at the edge of Mountain View. Page has spent more than $100 million on Zee.Aero.

In 2015, a second Page-backed flying-car startup, Kitty Hawk, began operations and registered its headquarters to a two-story office building on the end of a tree-lined cul-de-sac about a half-mile away from Zee’s offices. Kitty Hawk’s staffers, sequestered from the Zee.Aero team, worked on a competing design. Its president, according to 2015 business filings, was Sebastian Thrun, the godfather of Google’s self-driving car program and the founder of research division Google X. The first vehicle, The Flyer (tribute to the Wright Brothers), an octocopter whose twin pontoons enable it to take off and land on the water, was unveiled in 2017. Its controls are built into a set of handlebars and work similarly to the buttons and joysticks on a video game controller. The Flyer had been scheduled for demonstrations on Lake Winnebago at the EAA AirVenture seaplane base, though the demo was canceled because it was too windy.

Neva Aerospace is a European consortium in Brighton, England; Angers, France; and Vilnius, Lithuania, developing a heavy-duty EVTOL turbofan aircraft called the AirQuadOne. Basically a flying car, the AirQuadOne is designed to carry a single pilot at speeds up to 80 kph for up to 30 minutes at altitudes of up to 3,000 feet (900 m). The AirQuadOne is expected to weigh around 530 kg, including 150 kg of batteries for the full electrical version and 100 kg for the pilot. Neva expects the battery pack to be similar to or compatible with those of cars, with recharging at standard electrical stations via direct wire connection, induction or a battery pack switch. Neva is also looking at hybridization solutions for range extension. AirQuadOne was presented at the Paris Air Show in June 2017.

As part of the Goodwood Festival of Speed, held between June 29 and July 2, 2017, the Future of Speed Lab exhibit hosted the initial scale concept model of the NeoXcraft ducted-fan flying car. The vehicle was designed and created in Derby by VRCO, working with Institute for Innovation in Sustainable Engineering IISE, part of Derby University and home to the Rolls-Royce Innovation Centre. VRCO had recently signed a MOU with Astral LLC to build the world’s only neuro-mechanical holoportation drone platform.

In July 2017, the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) held its 65th annual fly-in convention at Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The world’s largest fly-in annually draws 10,000 airplanes to Wisconsin and a total attendance exceeding 500,000. India-born aeronautical engineer and entrepreneur Sanjay Dhall of Detroit Flying Cars exhibited his prototype with patented technologies that telescope, turn and lock wings that compress into the front and back of the two-seat vehicle when it’s on the road. Dhall’s flying car, featuring an electric engine for driving and an aviation engine for flying with a flight cruising speed of 125 mph (200 kph) and range of 400 miles (650 km), should make its maiden flight in 2018. Erik Lindbergh joined the VTOL hybrid-electric air taxi community with his Seattle-based VerdeGo (verde = green, vertigo) start-up.

In India, Naman Chopra, ex–Tesla Motors, now as chief product architect with Rexnamo Electro Pvt. Limited in Ghaziabad, U.P. India, co-launched his nation’s first Electric Highway—a network of fast chargers spanning the national capital region in the north to the Himalayas (Uttarakhand). The Electric Highway consists of a total of 12 fast chargers, allowing a 30-minute recharge to about 80 percent capacity for most EVs. The chargers consist of a 43 kW Fast AC option (Type-Two, or Mennekes connector, suits the Rexnamo Super Cruiser Bike) and two 50 kW Fast DC options—SAE Combo for the BMW i3, and ChaDeMo for Japanese makes of car. A slow charger is also located at each station, able to deliver up to 7 kW. A humble 15 amp GPO is also available. Close on its heels, Chopra launched the Rexnamo Roadable Aircraft®, a street-legal vertical takeoff airplane that converts between flying and driving modes in under a minute. A working prototype could be ready by 2018.

Paul J. DeLorean of Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, nephew of automobile manufacturer John DeLorean, formed DeLorean Aerospace in 2012 to design and build a flying car. Formerly a designer at Mattel, then General Motors, DeLorean began with a 30-inch (75-cm) scale model, then a one-third scale model to prove his concepts: incorporating a center-line twin vectoring propulsion system, stall-resistant canard wing at the front, the main wing at the back with small winglets underneath while two tandem seats in between hold the passengers. The full-scale DR-7, 20 feet (6 m) long and 18.5 feet (5.5 m) wide, will have wings that fold in so it can be parked in a large garage; its tests projected for 2018 will check out an autonomy approaching 200 km (125 mi) and whether its 1.21 gigawatt motor can give it a top speed of 88 mph (140 kph). The DR-7 will have an autonomous option. Paul DeLorean has been issued U.S. patent No. 9085355, with additional domestic and foreign patents pending. One recalls the DeLorean flying car in the movie Back to the Future.

If cars can fly, why not flying tricycles? The vision of pilot Captain Gary Lee Pylant and aerospace engineer Mark Rumsey of Spring Valley, Arizona, is the Fly-B, an electric-powered ultralight aircraft adapted to a modern lightweight recumbent tricycle frame, combining the best of both worlds: pedalectric bicycling and ultralight flying. With a flying speed of 62 mph (100 kph), the twin-prop Fly-B has a wing fitted with 24 ft2 (2.2 m2) of solar paneling to recharge its battery while parked and folds up for easy storage. A heart-rate monitor measures the pilot’s calorie burn.

The Hoversurf Scorpion 3, a quadcopter “motorcycle,” is the brainchild of Alexandr Atamanov, IT businessman and aviation enthusiast of Moscow and Los Angeles. Its wooden rotors enable it to fly up to 4 meters. After two years of R&D, this third-generation e-hoverbike was publicly launched in December 2016. Scorpion 3, which was demonstrated at the Moscow Raceway, Oblast, 97 kilometers from the city, can carry 125 kg and is capable of reaching 60 kph. Its battery capacity allows it to stay in the air for 15 minutes.2 In October 2017, it was announced that Dubai was planning to add Scorpion 3s to its police fleet. Also from Russia, weapons manufacturer Kalashnikov Concern, known for its AK-47 machine gun, the world’s most used weapon, demonstrated their unnamed 8 double-prop prototype, calling it a “hovercycle.” The batteries appear to be located under the rider linked to the rotors; the flying car has a seat and is maneuvered through the use of a joystick. Is this Russia’s new cavalry? Indeed there is another project for a quadcopter with a submachine gun and a 100-round magazine controlled by a smart tablet.

Another hybrid-electric flying car has been developed by the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory, sponsored by DARPA and contracted to Don Shaw and his team at Advanced Tactics of Torrance, California, as a Special Ops Transport Challenge. Built by Lockheed Martin, it was code-named the AT Black Knight Transformer to serve as both octocopter and truck, giving troops the flexibility to infiltrate enemy lines and evacuate wounded comrades from war zones. The first electric prototypes were flown in 2010, followed by a 2,000-lb gas-powered hybrid whose first test took place in March 2014 at the U.S. Army Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center. The prototype went up for sale on eBay a few days before Halloween 2017 to help fund development of a flying car called the AT Transformer (minus Black Knight), whose underbelly pods can hold from three to six people, cargo for disaster relief or resupply missions, or even wounded people on stretchers. AT states that it will be ready for sale by 2018. Alongside this, AT has developed the Panther package delivery mini flying car.

According to a report published by the Frost and Sullivan research and consulting organization titled “Future of Flying Cars 2017–2035,” over 10 companies are poised to launch flying cars by 2022, with OEMs and other major industry participants set to join them with prototypes in the following decade. At least eight companies have conducted flight tests in the past four years and several more have scheduled tests before the end of 2018. The report also identifies other uses for flying cars, including as air ambulances and for law and order, military and surveillance purposes.

It may not be long before flying cars enter into competition with each other.

For 2017, U.S. inventor Dezso Molnar announced a flying car race series, divided among three categories of vehicles: radio-controlled, electric, and unlimited flying cars. Radio-controlled vehicles are unmanned and guided by a human operator, while the others are both manned. Over the course, the vehicles must fly and drive 219 miles (352 km) from California’s El Mirage Lake, a dry lakebed, to the planned El Dorado Droneport in Nevada, near Boulder City. Radio-controlled flying cars will be raced within visual range of a control area. Twenty-two teams have been invited. On May 20, 2017, Molnar gave a presentation of his GT Gyrocycle and a talk, “How to Make a Flying Car That You Can Race,” at the Maker Faire Bay Area, San Mateo, California. Molnar’s Street Wing concept is a fully electric, solar-supported roadable airplane, and the G2 Gyrocycle is a race-focused, 200 mph (320 kph) three-wheeler that’s already rolling on the street, and nearly ready to fly.

With the aim of flying car races, over the past two years Matt Pearson and a team of five have been working in a Sydney warehouse in Australia to build the Alauda Mark 1 Airspeeder quadcopter with a top speed of 250 km/h (155 mph). With an aerospace aluminum frame and a carbon fiber composite body, it should have a net weight of 120 kg (265 lb.) and a power-to-weight ratio of 1.66. The plan is to make a test flight in 2018, followed by a head-to-head race between two of the single-seaters taking place in the south Australian desert late in the year. They’ll be unmanned at first, as the team works on the car’s safety systems. The first-ever Airspeeder World Championship, in which flying cars from different manufacturers race against one another, could subsequently be held in 2020.

The European Flying Car Association (EFCA) represents these national member associations on a pan-European level (51 independent countries, including the European Union Member States, the Accession Candidates, and Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, and Ukraine). The associations are also organizing racing competitions for roadable aircraft in Europe, the European Roadable Aircraft Prix (ERAP), mainly to increase awareness about this type of aircraft among a broader audience. EFCA members have launched the idea of organizing a European Grand Prix Competition for roadable aircraft (aka flying car). Because there are big differences in the technology used by the manufacturers, they believe there should be a competition per model or class of models. The races would, of course, have a driving part and a flight part. The weather will play an important role for these aircraft, so for safety reasons it may not be possible to plan the races exactly on a given date, unless the race tracks are designed in a way that allows the pilots to choose whether to finish the track only over road or also by air. Analysis should also be made of how filming is done with drones during drone competitions, like the World Drone Prix in Dubai. EFCA plans to organize the first races in 2018, if they manage to get all the necessary authorizations on time: ERAGP 2018 (European Roadable Aircraft Grand Prix 2018).

Eventually flying race cars may become driverless.