PLUCK

TERROIR

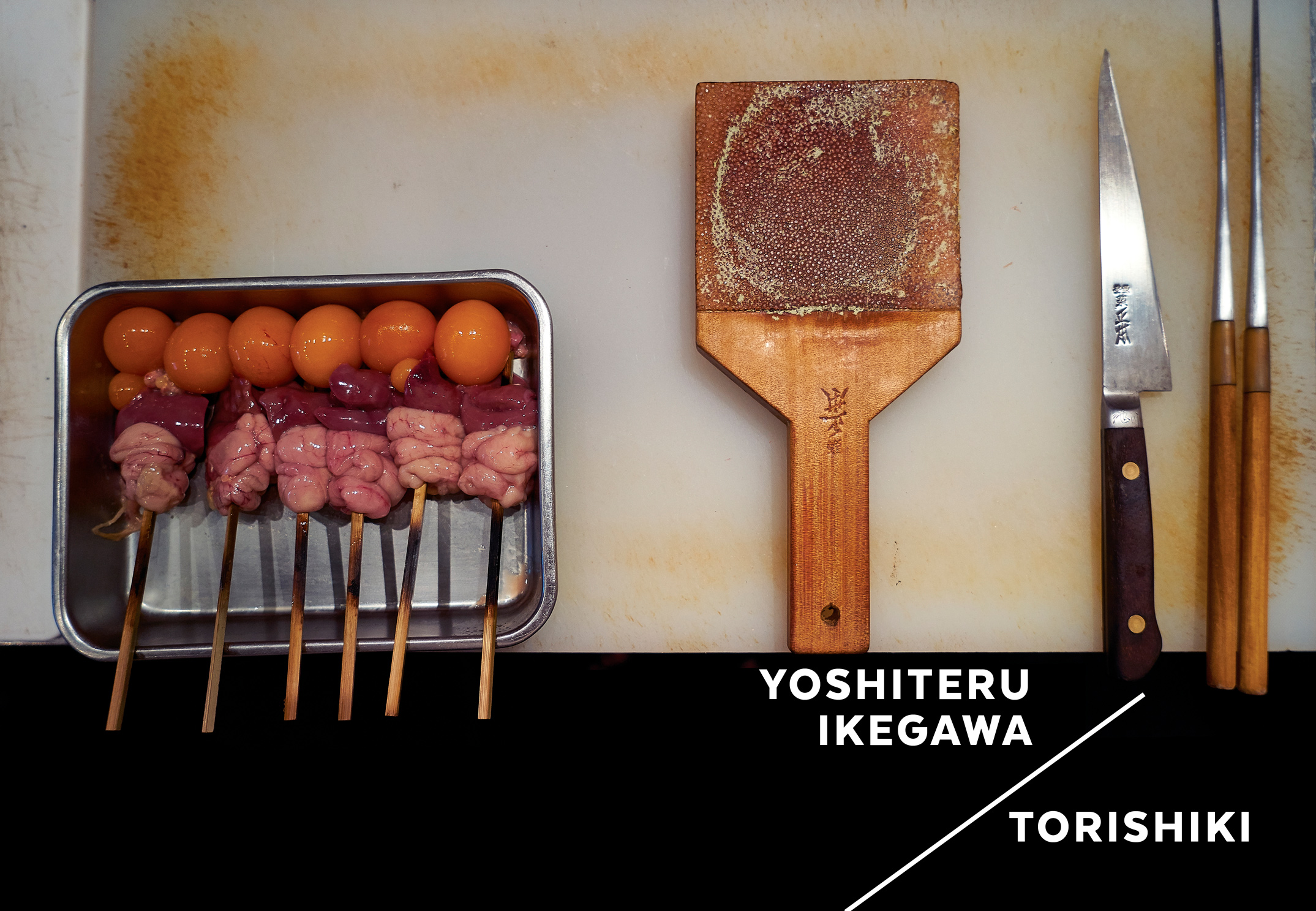

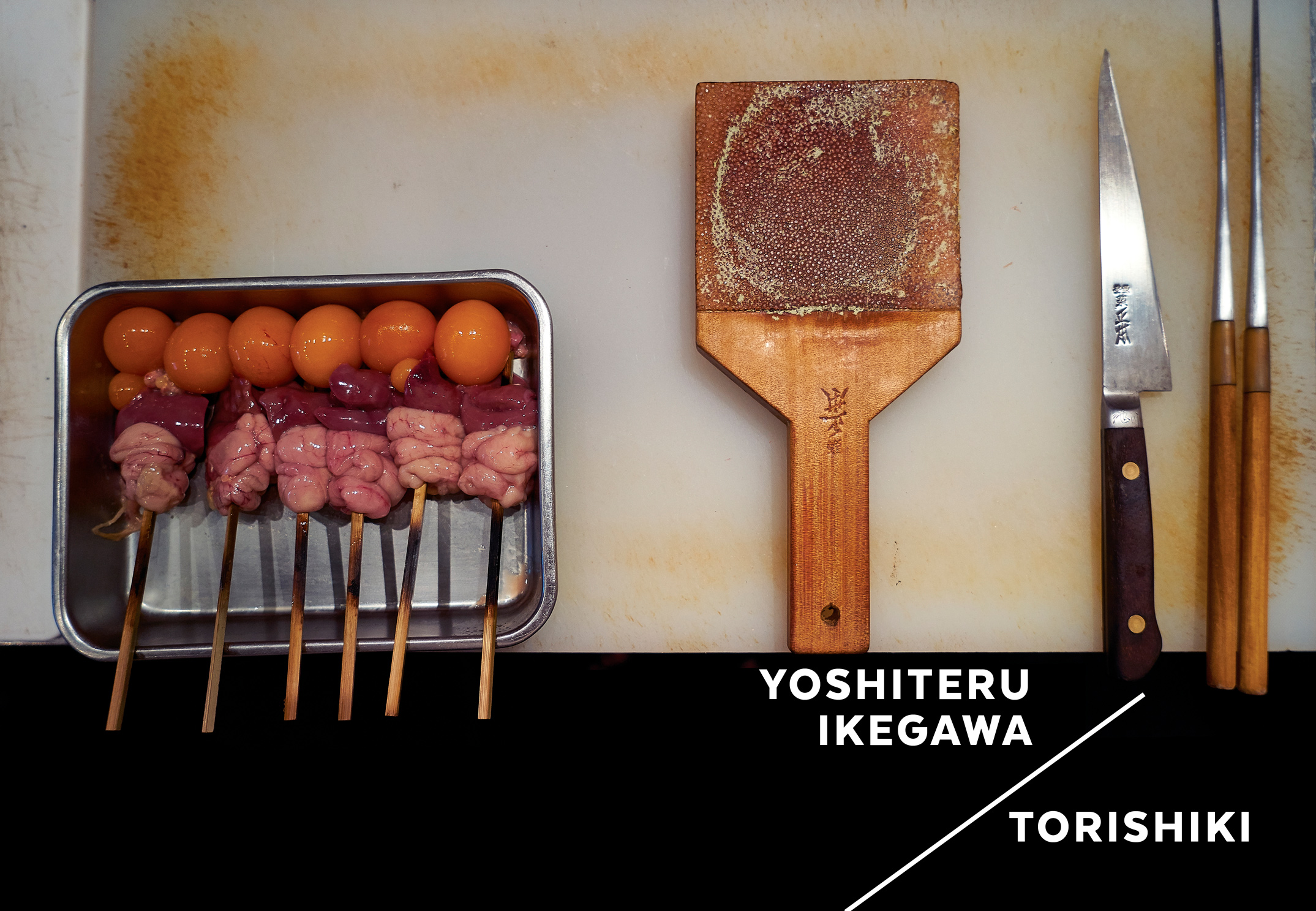

Yoshiteru Ikegawa’s rolled blue-and-white tenugui mameshibori (head scarf) sits perched atop his smooth, tan head. A soul patch dots his chin. His defined jaw, stature, and uniform recall the traditional figures of Edo- period woodblock prints. As he stokes the flames of the grill at Torishiki, his restaurant in Meguro, he admits that he has never been professionally photographed. They only come to photograph the yakitori, he says.

As a shokunin (master artisan) who does not profess to being one, Ikegawa believes that yakitori is one of the last remaining “analog cuisines” in Japan. His profound zeal for his craft is reflected in his enthusiasm for his materials: the charcoal and the chickens. As he preps his grill, looking up occasionally to smile, he explains how the odorless charcoal is alive and exudes intense energy both when lit and not lit. The chicken and vegetables absorb this energy during the grilling process, and as such, diners ingest, feel, and benefit from its energy. Dating back to the Edo period, the charcoal is called kishu binchō-tan and is from Wakayama Prefecture. It is ebony in color; the raw material is oak and as hard as glass.

I comment about the beauty of a shadow on the wall and Ikegawa smiles, exclaiming his stunned delight that I appreciate such a detail. This is one of the reasons I moved to Japan—to revel in the details with like-minded people.

The chickens Ikegawa serves are descended from French Bresse chickens and a domestic Japanese breed. They come from a farm near Iwate Prefecture, in the heart of the mountains, where they roam the open grassy spaces; the water is pure and the insects plentiful. Ikegawa tried many chickens before choosing this particular breed for Torishiki. They are the healthiest for the human body and have the most umami, he explains.

Ikegawa’s very first food memory is of eating yakitori in Tokyo; chicken has always been central to his life. He starts to fan the charcoal, pulling out a large ecru uchiwa (fan) from the small of his back. Isegawa begins to grill tsukune (ground chicken). He presents glistening skewers to me a few at a time, pacing the meal just as a sushi master would. His discreet attention to the rhythm of the meal makes for a graceful, perfectly timed experience. The finale is oyako-donburi, a hearty of bowl of chicken and egg over rice.

As I ready to leave, Ikegawa graciously gives me a bag of kishu binchō-tan. I am honored to accept his generous gift so that I can enjoy the charcoal’s organic energy long after my meal has ended.

Why do you cook?

Yakitori is very important to me; it is a big part of my life. Yakitori places are very local. When I was in elementary school, there was an entire street filled with yakitori vendors, like there used to be in Asakusa [a district in Tokyo]. I would buy one skewer of yakitori as a snack. I liked the smell of the charcoal. You don’t really cook yakitori at home, but by buying the yakitori, you can bring the charcoal smell home.

I wanted to be either a yakitori chef, a baseball player, or a high school teacher.

What is it about charcoal that you like so much?

Right now we are in a digital society, but charcoal is the opposite. It’s analog. Primitive.

What motivates you?

It’s important to me to be in the kitchen. I work about fourteen hours a day. I grill for about eight hours. I train mentally and physically. I need to be in shape. My sense of purpose is my restaurant. I want to protect it,make sure it is successful. When I first started, the restaurant was very local. Now we have reservations from people from all over the world. I couldn’t live without yakitori, and I want to share everything I know about yakitori and Japanese culture with my guests.

What is your definition of a shokunin (master artisan)?

Someone who puts his soul into what he does. Someone who knows his product so well that it’s instinctive. Sometimes customers ask me to make beef or pork yakitori, but I think yakitori should only be chicken. So I don’t do it. I think I am not yet a shokunin, but each day I work toward it. Every day I learn more.

What is your earliest food memory?

I was about five years old. When my dad finished work, he would go to a typical local izakaya with his friends, and sometimes he would bring me. There was always yakitori there. I remember the sauce and how delicious it was.

For you, what does it mean to be Japanese?

Okuyukashisa [telling someone something without saying it]. We are generally not good at self-promotion. Maybe something can be said just with energy or body language, without speech. This is beautiful to me. In old movies, actors would act without saying much. The use of silence is also quite Japanese to me. Timing, or ma—whether at a restaurant or a Kabuki performance. Knowing when to present food is very important. It should not be intrusive. We know when to serve and when not to serve.

Counter dining is wonderful for this reason. I always tell my staff to use their five senses: smell, sight, taste, touch, and sound. For example, if a customer spills something, it is up to us to anticipate her needs before she asks for help. Some customers tell me I have eyes in the back of my head.

If you could share a meal with anyone, who would it be?

My wife and my parents. There is no one who is famous who I am interested in meeting.

What is your favorite word?

Honesty.

What is one of your favorite films?

The Godfather, for the family love. My staff is also my family. The relationships portrayed and the strong and intense spirit of the film are appealing to me.

CHICKEN AND EGG OVER RICE (OYAKO-DONBURI)

Invented about 130 years ago here in Tokyo, oyako-donburi is also known as Oyakodon, which literally means “parent and child donburi”—the parent and child is the chicken and the egg. Donburi is a rice bowl dish, usually made with simmered meat, fish, or vegetables that is served over rice with a thin layer of lightly cooked egg on top.

SERVES 1

OYAKO SAUCE

1 cup chicken broth

½ cup plus 1 tablespoon mirin

½ cup plus 1 teaspoon soy sauce

5 tablespoons sugar

OYAKO-DONBURI

2 boneless skinless chicken thighs or 1 boneless skinless chicken breast, cut into bite-size pieces

3-inch piece of leek, chopped

½ cup steamed Japanese short-grain white rice

Shredded nori, to top the rice

2 eggs, separated and lightly whisked in two bowls

Fresh mitsuba or cilantro leaves, for garnish

To make the oyako sauce, combine all of the ingredients in a sauté pan and bring to a boil over medium heat for about 5 minutes, until the sugar has dissolved and the sauce has thickened. Remove from the heat and pour into a bowl.

To make the oyako-donburi, add the chicken and leek to the oyako pan or a 6-inch nonstick sauté pan with ¼ cup oyako sauce and cook over low heat. When the mixture starts to boil, turn the chicken to cook evenly and simmer 5 minutes, turning occasionally, until cooked through or to your desired doneness.

Meanwhile, put the rice in a bowl and layer the nori over the top, making sure that the rice is completely covered. Keep warm.

Pour the egg whites in a thin stream onto the chicken in a circular pattern. Separately, add the egg yolks in four distinct places around this circle. All of the egg whites and egg yolks should be used. Shake the pan and tilt it a bit right and left for about 6 seconds to spread out the ingredients, allowing them to cook equally. Make sure that the egg does not touch the sauté pan’s surface, which would cause it to overcook. Cover the pan, raise the heat to high, and cook for about 1 minute, until the egg has cooked through. Uncover the pan and quickly transfer everything to the bowl with the rice by sliding it out of the pan. Garnish with a mitsuba leaf and serve right away.