RIGOR

SOPHISTICATION

I enter through a door framed in white neon and climb a flight of stairs to Takazawa. Engraved in the bannister is an excerpt from a poem by American poet Joyce Kilmer: “I think that I shall never see a poem as lovely as a tree. Poems are made by fools like me, but only God can make a tree.”

The interior is small, urbane, and rich in dark hues, except for a striking illuminated central steel island that resembles a hypermodern altar—this is where Yoshiaki Takazawa holds court. Members of his team occasionally appear from behind an obscured black door to provide an ingredient or briefly assist, but by and large Takazawa is out there on his own, controlling every aspect of service. His wife, Akiko, is a constant and courteous presence who explains the simultaneously cerebral and whimsical dishes.

Dining at Takazawa is based on the Japanese tea ceremony. With only five tables and no counter, each guest can enjoy Takazawa’s tremendous focus during service. There is no chitchat, though he occasionally comes from behind the island to present a dish himself. He is an intense, distinguished, and precise maestro. His longish salt-and-pepper hair is meticulously set in place so as not to fall in front of his eyes. His goal is to host his guests with originality and sophistication, in his clever, contemporary way.

Although Takazawa seems businesslike during service, there is a playfulness and inventiveness to his luxurious dishes, a hallmark of molecular gastronomy. One dish, Fish and Chips, features edible paper; another called Candle Holder presents foie gras in a glass pot with a crème brulee–like glaze, resembling a scented candle; and another is Ratatouille, a bite-size vegetable terrine that recalls a mosaic of multicolored jewels. While Takazawa’s style of cuisine is distinctly global, it is steeped in Japanese soul.

When I taste his dishes, I recall textures, colors, scents, and vistas from Vietnam, Russia, England, and Italy—all in one tour-de-force meal. Interestingly, Takazawa never trained abroad, though he embraces countless international themes and techniques with bravura and expertise.

After service, we sit to chat in his nearby lounge, Takazawa Bar, and I discover he speaks English. He opens up and conveys a much more relaxed demeanor outside of service hours, especially as he lovingly recalls his grandmother. I learn that she cultivated his imagination and love of food early on. For all the restaurant’s rigor, worldly cultivation, and panache, it is the simple memories of time with his grandmother, visiting gardens and enjoying food together, that are at Takazawa’s core.

Why do you cook?

My parents had a restaurant in Koenji. I grew up in their kitchen and had a number of responsibilities. But I wanted to be a Japanese chef for my grandmother. My parents were very busy. Every day after elementary and junior high school, I would go home to my grandmother and she would cook for me. She would sometimes bring me to the park, like Jindai Botanical Park in Mitaka [western Tokyo]. To this day, whenever I see flowers I think of her. I loved her and loved being with her.

What motivates you?

When I graduated from culinary school, I was at the top of the class. At graduation, I was to have received the best award, but the teachers didn’t like that I would correct them. Only one teacher liked me. They said I was a bit too blunt and honest. They told me I wouldn’t be a successful chef, but I wanted to prove them wrong.

What is your earliest food memory?

When I was a kid, about four or five, I was playing with some cooking tools, like a veggie slicer, and I cut my finger. I was cutting a cucumber with a mandoline and didn’t realize I was cutting my finger.

For you, what does it mean to be Japanese and how do you think growing up in Japan informs your style?

Nowadays I have many chances to go to other countries to meet many foreigners. After we travel and come back to Japan, I always feel that Japan is convenient, comfortable, and peaceful, with very tasty food as well.

Details are very important, and so is an interest in learning. In the restaurant industry in Japan, we are educated by older chefs who are very strict. Now, however, this is a changing a bit.

We respect the seasons and ingredients. Because of my grandmother, I understand the seasons. I want the customer to understand where they are eating, what they are eating, and why they are eating it at that particular moment in time.

What is tough about your industry?

Working in the restaurant industry is very hard work, with long working hours. Chefs’ lives are shortened once they become head chef. It’s a stressful life physically and mentally. We are like athletes. But I would like to change this. I’d like staff to stay longer and stick with things longer; they are impatient. We need to change the dynamic in society, where cooks get low pay for long hours.

What is your favorite word?

Passion.

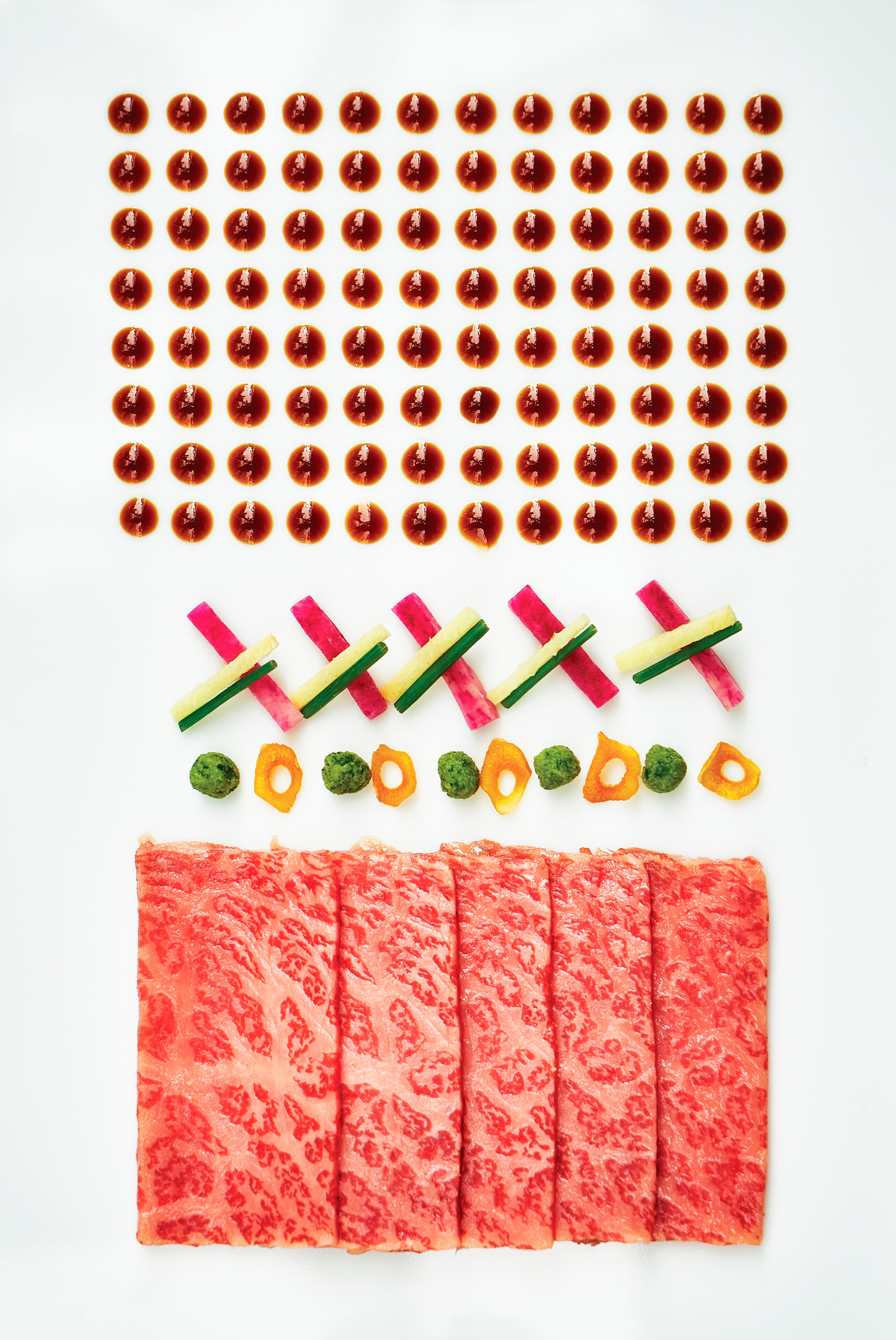

TAKAZAWA SASHIMI

Classic sashimi dishes are traditionally simple sliced fish with soy sauce. I wanted to do it in a more modern way with a twist. So I played with and updated the presentation to make it a bit more unexpected.

SERVES 4

LEEK OIL

1 tablespoon coarsely chopped leeks

4 teaspoons olive oil

3½ tablespoons soy sauce

3½ tablespoons tamari, at room temperature

1½ teaspoons agar agar powder

1 red daikon radish, cut into 12 bâtonnets

2 chives, cut into 12 bâtonnets, plus ½ teaspoon chopped fresh chives

12 bâtonnets fresh peeled ginger, plus 2 tablespoons grated ginger, from about 1 piece fresh ginger

4 cloves garlic, peeled

10 ounces sashimi (any seasonal, high-quality Wagyu beef or sushi-grade fish) or 20 slices, each about 3 by 1½ by ½ inches

To make the leek oil, crush the leeks in earthenware mortar and pestle. Mix in the olive oil and continue crushing until coarsely ground, not smooth. Set aside.

In a small bowl, stir together the soy sauce, tamari, and agar agar powder until the mixture thickens enough so that a drop of it on a plate will keep its shape. Decorate a serving platter large enough to fit all of the sashimi with 96 dots of this mixture in 8 lines on the top of the platter.

Arrange the radish, chives, and ginger bâtonnets in small crosses in the center of the plate.

In a small bowl, stir together the grated ginger and chopped chives until it clumps into little balls, then place them on the platter next to the vegetable bâtonnets. Slice the garlic ⅛ inch thick. In a small pan, cook the garlic in the leek oil over medium heat, stirring frequently, until the garlic is light brown and crisp, about 15 minutes. Transfer the garlic chips to a paper towel to absorb any extra oil, then place them in between the balls of grated ginger and chives.

Just before serving, arrange the slices of sashimi on the platter below the other ingredients.

NOTE: A bâtonnet cut is a vegetable cut into batons or sticks, in this case 1 by ⅜ by ⅛ inches.