Man and computer

‘Human chess is blind, a man cannot see the whole board which the universe has placed before him.’ – Milan Vidmar

In the 21st century, the face of the chess world has changed sharply, thanks to the emergence into the ancient game of the latest computer technology. Humans started losing games against machines and it soon became clear that a man could not hope to compete with the computer in positions depending on calculation. Many famous games and chessboard achievements suddenly lost their lustre and faultlessness under the gaze of the computer. The computer had gradually encroached on the space of free human thought and is already able to give definite assessments and analyses of any position with seven or fewer men on the board. One involuntarily begins to have doubts as to whether the old methods of training will still be effective in this brave new world. Is it still worth studying classic games and annotations, when the computer so often points out tactical oversights in them? Is it still worth doing one’s own analytical research, or should one just pass this job entirely over to our ‘silicon friends’?

By way of an answer to these questions, it is useful to consider the subtle observations of the grandmaster and trainer Vladimir Tukmakov from his book The Key to Victory (2012), which portrays the relationship between the player and the computer, at the highest level of chess: ‘The study, search for and assessment of opening variations takes a massive amount of time and energy for the modern grandmaster. The relationship between home preparation and play is shifting more and more in favour of the former. Whereas in older times, home preparation was just a prelude to real action over the board, nowadays, independent play and improvisation at the board tends to be seen as a sign of an annoying failure of home preparation. A player frequently comes to the board tired and worn out, with barely enough energy to recall and execute the complicated computer analyses. The modern player also faces one other danger. The ease with which one can obtain the all-knowing computer’s suggestions tends to foster an illusion of simplicity. In the pre-computer era, every new idea, every quality piece of analysis, required great effort and hard work. The process was no less valuable than the result. In the search for the answer, much that was new was discovered and, even if the ultimate search proved fruitless, the work done was not in vain. These days, the unexpected departure over the board from the anticipated line of preparation frequently produces something akin to shock, because the line being followed was not governed by the player’s logic or understanding, but was simply the opinion of the computer. As a result, we see a widening gap between faultless opening play, satisfactory middlegame play and then very often a flop in the endgame. At this stage of the development of chess it is not so much about the absolute harmony of all these elements, as about some sort of harmony between them. Here there is also great scope for improvement. And for a young player who notes this modern tendency it will be significantly easier to achieve a new level of mastery.’

I should like to reassure the young reader – the problems of grandmasters (many created by the GMs themselves) need not be taken to heart. For the present, childhood, when so many new worlds are opened up and so many striking impressions are revealed, remains the happiest time of one’s life. The same is true in chess – this is when we accumulate knowledge, discover the beauty of the game, fantasise, argue, search for the truth, play, risk, etc. We should by no means compare our every move with that of the computer. Later, once having gained experience and formed our understanding of chess, we can engage with the computer, secure against its hypnotic influence on our own independence of thought. In this chapter, I want to discuss in simple terms the successes and failures in the ‘thinking’ of the electronic GM.

Probably, dear reader, you have had moments of disappointment, when the computer has solved in seconds an endgame study or immediately found a combination which you yourself played over the board, only after long thought and with the aid of a great piece of creative imagination. The electronic GM, thanks to its enormous speed of processing, has replaced the intuitive searching of a human with what the programmers call ‘brute force’. Pessimists believe that in the future, all the secrets of chess will be revealed by the computer (i.e. it will succeed in analysing out all of the game’s possibilities) and it will become a game where the result is known. In opposition to this view the optimists believe that these gloomy predictions will not come true and that the ancient legend of the invention of the game and of the grains of wheat will be fully realised. Personally, I am sympathetic to the words of Boris Vainshtein in his booklet Ferzberi’s Traps (1990): ‘Chess is not inexhaustible purely because of a very large number of possibilities, a number too great for us even to imagine. Rather, chess is inexhaustible in the same way as music! Music does not consist of numerous variations on the possible combinations of notes, but of something internal, its emotional content. Chess is the same: the size of his cosmic library of possibilities means nothing to us, as far as our conception of it is concerned as an artistic competition, based on knowledge, logic, ideas, etc. And the inexhaustibility of chess is not in numbers of variations, but in an inexhaustible idea, resulting from the collision of intellects.’

Now let us move on from general discussions to questions of concrete practice interest. There is no question that in matters of calculation, the computer is extraordinarily accurate and far-seeing. The tactical resources pointed out by the computer can be extremely hard for the carbon-based chess player to see and require special chess/psychological thought processes. As a rule, the human will overlook ideas which breach established principles and it is useful to pay attention to this issue.

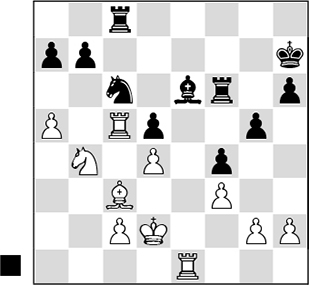

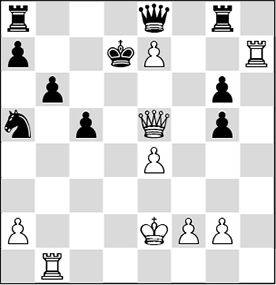

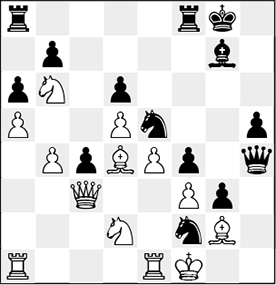

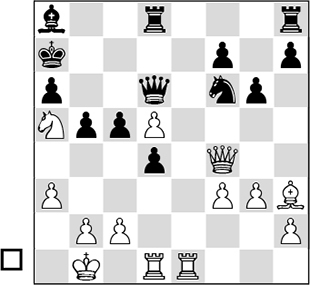

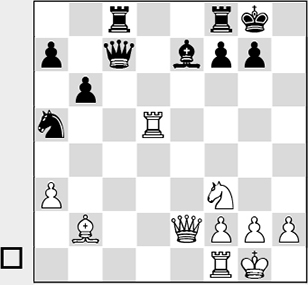

By way of illustration, let us look at a simple example. Not so long ago, in search for exercises for a training programme, I looked through a collection of Smyslov’s Best Games. My attention was attracted by the following position:

Vasily Smyslov

René Letelier Martner

Venice 1950

White has just played 27.♘d3-b4, and after 27…♘xb4 28.♖xe6 ♖xe6 29.♖xc8 ♘c6

30.a6! bxa6 31.♖c7+ ♔g6 32.♖d7 ♘e7 33.♗b4 ♘f5 34.♖xd5 he obtained a strong passed pawn in the centre. In his notes to the game, Smyslov points out that ‘the continuation 27…♘e7 allows an effective combinational blow: 28.♘xd5! ♘xd5 29.♖xe6! ♖xc5 30.♖xf6 ♘xf6 (or 30…♖xc3 31.♖d6, and White regains the piece, keeping an extra pawn) 31.dxc5 ♘d7 32.♔d3! ♘xc5+ 33.♔c4, and the white king goes after the black queenside pawns.’

Is the ex-World Champion’s variation correct?

In his notes, Smyslov committed an error. After the moves 27…♘e7 28.♘xd5 ♘xd5 29.♖xe6 ♖xc5 30.♖xf6

the computer immediately points out the unexpected (for the human player) refusal of all captures – 30…♖c7!!, and Black wins a piece. And yet how many players (myself included) have studied this classical game without anyone noticing this resource!

However, one must also note that the electronic GM also has its weaknesses. There is an interesting comment by Alekseeva and Razuvaev (in the article ‘School, the computer and chess’ 2003): ‘In terms of depth and accuracy of calculation, the human is helpless before the ‘silicon beast’. But nature has endowed the human with a wonderful panorama of vision and at the present moment, he still exceeds the computer in that respect.’

Let me illustrate this with some examples.

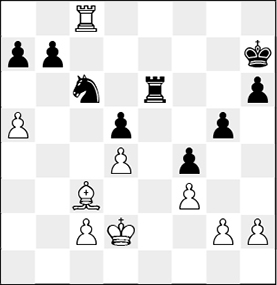

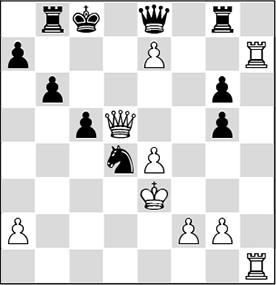

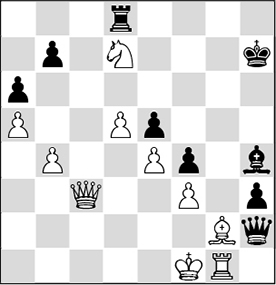

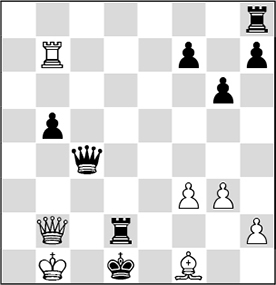

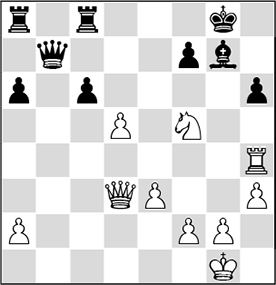

Viswanathan Anand

2783

Vladimir Kramnik

2772

Bonn Wch-match 2008 (7)

In this position, taken from a World Championship match, the players agreed a draw. In his commentary, Alexander Khalifman noted that ‘It is surprising that all the best computer programs assess the final, dead-drawn position as clearly in White’s favour. It seems their programmers still have some work to do.’

How could this happen? The fact is that the human is able to assess this position very quickly, because his general strategic grasp tells him that the white material advantage is of no use, because there are no squares in the black camp to which he can penetrate.

The computer, however, does not think in such ‘general’ terms – it simply calculates variations. After penetrating 18 moves deep into the position, the computer still sees an extra pawn and a space advantage for White!

That the computer has trouble with positional fortresses has long been known, but it is inconceivable that it should also be weaker than a human in calculating combinative complications. However, look at the following game. Vaiser’s comments on the key moment made a great impression on me at the time:

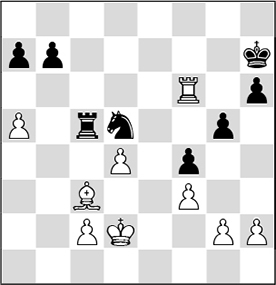

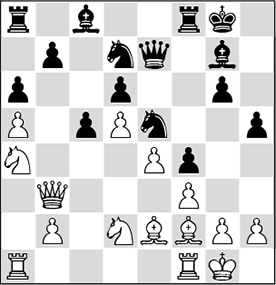

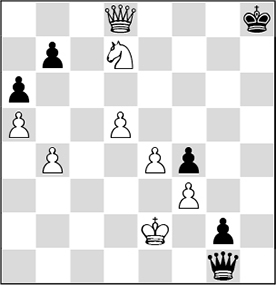

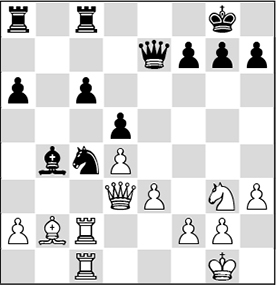

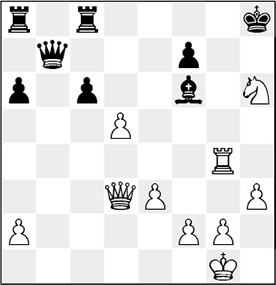

Grünfeld Indian Defence

Anatoly Vaisser

2576

Maxime Vachier-Lagrave

2527

Chartres ch-FRA 2005 (7)

‘With the help of the computer, my young opponent had prepared an interesting novelty in a long theoretical variation, which is considered to be dubious for Black. When after a long think, Fritz pronounces a large advantage, then in 9 cases out of 10, it is indeed a large advantage. Maxime’s mistake was that the deep position arising in the game was incorrectly assessed by the computer. The reason is very unusual – zugzwang in the middlegame.’

After the well-known moves

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.cxd5 ♘xd5 5.e4 ♘xc3 6.bxc3 ♗g7 7.♘f3 c5 8.♖b1 0-0 9.♗e2 ♘c6 10.d5 ♗xc3+ 11.♗d2 ♗xd2+ 12.♕xd2 ♘a5 13.h4 ♗g4 14.♘g5 ♗xe2 15.♔xe2 h6 16.♘f3 ♔h7 17.♕c3 b6 18.♘g5+ ♔g8 19.h5 hxg5 20.hxg6 fxg6 21.♖h8+ ♔f7 22.♖h7+ ♔e8 23.♕g7 ♔d7 24.d6 ♕e8 25.dxe7 ♖g8 26.♕e5

the following position arose:

26…♔c8

‘Finally the novelty. Vachier had played all 26 moves at blitz pace. In the stem game Chernin-Stohl (Austria Bundesliga 1993) there followed 26…♘c6? 27.♖d1+ ♘d4+ 28.♖xd4+! cxd4 29.♕d5+ ♔c7 30.♕xa8! ♕b5+ 31.♔f3 ♖e8 32.g3!, and White eventually won.’

27.♕d5!!

A powerful move, which decides the outcome of the game. The silicon beast considers it to be bad, clearly preferring 27.♖d1?, which allows 27…♕b5+ and 28…♖e8.

27…♘c6 28.♖bh1 ♘d4+ 29.♔e3 ♖b8

30.g4!

‘A most unlikely position! The black pieces turn out to be in zugzwang in the middle of the game. But this move is already outside the computer’s horizon. This explains why Fritz mistakenly assesses Vachier’s novelty at move 26.’

30…♖b7

Or 30…a5 31.a4 ♘c2+ 32.♔f3 ♘d4+ 33.♔g2.

31.♕xg8! ♕xg8 32.♖h8 ♖xe7 33.♖xg8+ ♔b7 34.♖xg6 ♖f7 35.♖h3 ♘c2+ 36.♔e2 ♘d4+ 37.♔f1 1-0

Some time later, I had a case in my own experience, which confirmed the computer’s vulnerability in judging positions at the end of long tactical variations.

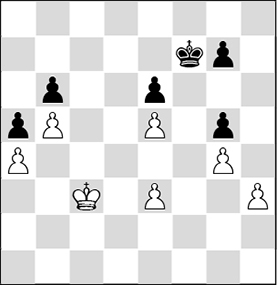

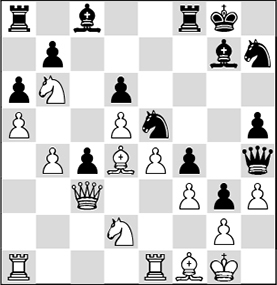

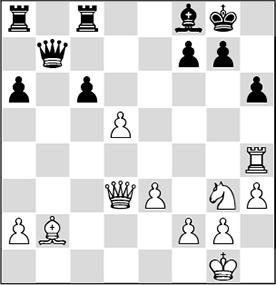

King’s Indian Defence

Edward Duliba

Alexander Kalinin

XXI cr 2007 (7)

In 2006 I gave up playing tournaments, to concentrate on training work. From time to time, I quench my craving for competition by playing in postal chess tournaments. I should add that I had played successfully in several such events at the end of the 1980s, during my army service. Sadly, I soon realised that over the intervening 20 years, postal chess had changed beyond recognition. Now one is playing against a computer and can oneself also make use of its help. In my view, such play has no relation to chess and is more like a scientific experiment aimed at finding the best way to fight against the computer.

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 ♗g7 4.e4 d6 5.f3 0-0 6.♘ge2 c5 7.d5 e6 8.♘g3 exd5 9.cxd5 h5 10.♗g5 ♕b6 11.♕b3 ♕c7 12.♗e2 a6 13.a4 ♘h7 14.♗e3 ♕e7

In the game Dreev-Topalov (Elista 1998) there followed 14…♕e7 15.0-0 ♘d7 16.f4 ♗d4 17.♗f2 h4 18.♘h1 g5 with mutual chances.

15.♘f1 ♘d7 16.♘d2 f5 17.a5 f4 18.♗f2 ♘g5

This knight is aiming at the e5-square, whilst its colleague remains on d7 for the time being, restricting possible enemy entry to b6.

19.♘a4 ♘f7 20.0-0 ♘fe5

The white pieces, to my mind, are quite clearly being conducted by a computer. He has allowed his opponent to achieve everything a KID player can dream of – an open diagonal for the ♗g7, a knight secured on the blockading e5-square, and the kingside pawns ready to go in motion. But the machine does not bother with such general considerations.

The ‘calculations’ show a clear advantage… to White! Think of it for yourself – the threatening ♘e5 and ♗g7 are not so strong, the kingside pawn advance does not threaten anything yet, and the black queenside pieces are not fully developed. At the same time, the excellently developed white army is ready to break through on the queenside with b2-b4… But which side would you rather play in this position, dear reader?

21.♕a3 g5 22.b4 c4

The pawn on c4 is dropping off, but I did not wish to allow the opening of all the queenside lines, that would follow after 22…cxb4. However, the computer advises Black to keep material equality.

23.♗d4 g4 24.♕c3 g3 25.h3 ♕h4 26.♖fe1 ♘f6 27.♗f1 ♘h7 28.♘b6

28…♗xh3

I did not even look at playing with material equality after 28…♘g5 29.♘xc8. A KID player knows very well that without the light-squared bishop, he has practically no chances of breaking through the enemy king’s defences. As you have probably guessed, the computer recommends refraining from the bishop sacrifice.

29.gxh3 ♘g5 30.♗g2 ♘xh3+ 31.♔f1 ♘f2

32.♘dxc4

White does not expend time taking the ♖a8, the priority instead being to take action to neutralise the activity of the ♘e5 and ♗g7.

32…♕h2 33.♗xe5 dxe5 34.♘xa8 h4 35.♖e2 ♖xa8 36.♘b6 ♖d8

After 36…h3 37.♖xf2 gxf2 38.♗xh3 ♕xh3+ 39.♔e2 Black has a strategically lost position, with a ‘dead’ bishop on g7.

The retreat of the black rook to d8 is explained by the fact that after the more natural 36.♖f8 it will later come under attack from the white knight on d7.

37.♖xf2 gxf2 38.♔xf2 h3 39.♖g1 ♗f6 40.♘d7

If 40.♔f1 ♔h7 41.♗h1 ♔h6!? White’s extra piece is not of any special significance.

40…♗h4+ 41.♔f1 ♔h7

White does not lag behind his opponent in sacrifices! By clearing the pawns from the centre, White initiates a counterattack against the black king. I was reluctantly forced to realise that the sharp advance of the black kingside pawns was not only an attack on the white king, but also exposed Black’s own monarch!

42…hxg2+ 43.♔e2 ♕xg1

To this day I do not know if 43…♕g3, recommended by the computer, leads to a draw, because I have not especially analysed it. My attention was immediately attracted by the text move, which the computer considers a serious mistake and leads to a position where the machine gives the unprecedented assessment of +5.00 in White’s favour.

44.♕h5+ ♔g7 45.♕g4+ ♔h8 46.♕xh4+ ♔g7 47.♕g5+ ♔h8 48.♕xd8+

By giving endless checks, White has more than regained the sacrificed material. The whole question now is whether the passed pawn on g2 will compensate Black for his large material deficit, or whether White will succeed in weaving a mating net around the black king. To the human, the essence of the problem is clear, but the computer does not realise it, even in the course of 20-30 moves! This happens because White has an enormous number of checks, none of which, however, change things, and the real assessment of the position remains hidden behind the computer’s horizon.

48…♔g7 49.♕f8+ ♔h7 50.♘f6+ ♔g6 51.♘g4 ♕f1+ 52.♔d2 ♔h7!

The only defence, but sufficient.

53.♕e7+ ♔h8 54.♕d8+ ♔g7 55.♕c7+ ♔h8 56.♕c8+ ♔g7 57.♕xb7+

With the disappearance of the b7-pawn, the position changes and White obtains another ‘million’ checks.

57…♔h8 58.♕c8+

Perpetual check, but this time to the white king, follows after 58.♘f6 ♕f2+. An interesting situation arises after 58.♕b8+ ♔h7 59.♕a7+ ♔h8 60.♘f6.

It seems as though Black is in trouble, since after 60…♕h1 White decides things with 61.♕b8+ ♔g7 62.♕g8+! ♔xf6 63.e5+! ♔xe5 (Black also loses after 63…♔e7 64.♕g7+ ♔e8 65.e6) 64.♕e6+ ♔d4 65.♕e4#. But Black has a saving combination: 60…♕c1+! 61.♔xc1 g1♕+! 62.♕xg1 – stalemate! In the game, things ended more prosaically.

58…♔g7 59.♕d7+ ♔h8 60.♕e8+ ♔g7 61.♕e7+ ♔h8 62.♕f8+ ♔h7 63.♘f6+ ♔g6 64.♕g8+ ♔xf6 65.e5+ ♔e7 66.d6+ ♔d7 67.♕d5 ♕f2+ 68.♔c3 ♕e3+ ½-½

So, how should we assess the position arising after 20 moves in this game? Maybe the computer was right, since Black had to sacrifice material and only saved himself by a miracle? I will not hide the fact that I believed the position was clearly better for Black and was extremely optimistic. But even now, I am convinced that in a practical game between humans, Black’s position is easier to play. The computer, even when its king is under strong attack, can never lose its head, which can hardly be said of a human player. The assessment of complicated positions often depends on the personal characteristics of the players. Another interesting question is: how far, in these days of computers, should a player calculate variations, before deciding on a sacrificial combination over the board?

Let us consider the next example.

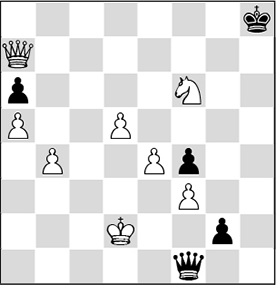

Garry Kasparov

2810

Veselin Topalov

2700

Wijk aan Zee 1999 (4)

The unexpected blow 24.♖xd4!!? served as the start of a grandiose sacrificial idea by the 13th World Champion. Topalov accepted the sacrifice, but later it was discovered that 24…♔b6!! would have allowed the white attack to be beaten off. Alexander Beliavsky and Adrian Mikhalchisin, in their book Intuition in chess (2003), commented as follows on the events of the game: ‘Here Kasparov had the chance to choose between 24.♘c6+ ♗xc6 25.♕xd6 ♖xd6 26.dxc6 ♔b6 27.♖e7 ♔xc6 28.♖de1 with the threat of 29.♖a7 ♔b6 30.♖ee7 with at least a draw, and the active 24.♖xd4?!. As Kasparov himself put it: ‘For the first time in my life, I calculated a variation 18 moves deep!’ (further than the computer – AB and AM.). But this calculation hardly made sense for either player – after 24.♖xd4?! ♔b6! 25.♘b3 ♗xd5! 26.♕xd6+ ♖xd6 27.♖d2 ♖hd8 28.♖ed1 c4 29.♘c1 ♔c7 and the further exchange of rooks, it is very hard for White to save the endgame. This variation was intuitively rejected by both players and Black instead plunged into the complications.’

24…cxd4 25.♖e7+! ♔b6 26.♕xd4+ ♔xa5 27.b4+ ♔a4 28.♕c3 ♕xd5 29.♖a7! ♗b7 30.♖xb7 ♕c4 31.♕xf6 ♔xa3 32.♕xa6+ ♔xb4 33.c3+ ♔xc3 34.♕a1+ ♔d2 35.♕b2+ ♔d1 36.♗f1! ♖d2

37.♖d7! ♖xd7 38.♗xc4 bxc4 39.♕xh8

In playing his 24th move, White had calculated the main line up to this moment. Black’s position is lost and he soon resigned. ‘Much ado about nothing!’ concluded Beliavsky and Mikhalchisin.

I think that most chess lovers, thankful for the present of the beautiful combination presented to them by the 13th World Champion, would not agree with the esteemed grandmasters. By sacrificing the rook, White posed his opponent a difficult problem, which the latter failed to solve successfully in the conditions of a complicated and tense game over the board. In such a case, it is appropriate to remember Alekhine’s words: ‘At the end of the day, chess is not just knowledge and logic!’

In this last example, as well as Kasparov’s fantastically deep calculation, I was also astonished by his comment in his annotations, that if, in the start position, the black rook had stood not on h8 but g8, then the entire combination would have been unsound! It turns out that the fate of such a brilliant idea depends on a seemingly insignificant detail, revealed only some 20 moves later in the combination.

It is obvious that not every player, even of the highest class, could perform such lengthy and detailed calculation. So what should one do – refrain from the combination because one cannot calculate everything out to the very end, or go for the sacrifice anyway, trusting one’s judgement of the position? The answer to this question has already been provided by the play and writings of such creative attacking players as Spielmann, Tal and Shirov. The fact that the powerful modern-day computers occasionally find a hole in the analyses of such intuitive human combinations does not change anything fundamental. Humans always make mistakes and all the while chess is played by humans, it is a battle, in which there is an element of risk!

Let us quote a few observations by Rudolf Spielmann, from his famous book The Art of Sacrifice:

‘If you require from every sacrifice undoubted, analytically-demonstrable proof of correctness, then you will strip all elements of risk out of chess. But this would effectively eliminate all real sacrifices, leaving only those which, strictly speaking, cannot really be regarded as sacrifices at all.’ […] ‘At the critical moment, it is only possible to calculate that for the piece, White obtains two pawns and an ongoing attack. Whether it will end in victory is a matter of judgement… As a rule, it is extremely difficult to analyse sacrifices fully, covering every possible variation, even just a few moves; more often, such an expenditure of precious time and energy leads to nervous exhaustion, time trouble and an undeserved defeat… A good chess player should be able to calculate, but should not do so to excess. My comments, of course, apply to tournament games over the board, with limited thinking time. For postal play, one must have a different approach and here one can strive for accurate and complete analysis.’

The attempt over the board to calculate a long and complicated set of variations to the very end is a fruitless endeavour, as such a thing is beyond human capability. There are some cases, however, where even unlimited home analysis, with the computer’s help, fails to reveal the definitive answer to a position.

By way of illustration, I offer another of my correspondence games.

Slav Defence

Alexander Kalinin

Vladimir Napalkov

cr Abramov Memorial 2006/2007

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.♘c3 a6 5.e3 b5 6.b3 ♗g4 7.♗e2 e6 8.0-0 ♘bd7 9.h3 ♗f5 10.♗d3 ♗b4 11.♗b2 ♗xd3 12.♕xd3 0-0 13.♖fc1

In this quiet variation, White retains a minimal advantage, thanks to his growing pressure on the c-file.

13…bxc4 14.bxc4 ♕e7 15.♖c2 ♘b6 16.♘e5 ♖fc8 17.♘e2 ♘fd7 18.♘xd7 ♘xd7 19.cxd5 exd5 20.♖ac1 ♘b6!

The defence of the c6-pawn hangs on this manoeuvre. After 20…♘b6 21.♖xc6 ♖xc6 22.♖xc6 ♘c4 the white rook is trapped and the exchange sacrifice for two pawns with 23.♖xc4 dxc4 24.♕xc4 ♕b7 does not offer any special prospects.

21.♘g3

Preparing for active operations on the kingside.

21…♘c4

The critical position, in which White must either settle for empty equality or head for irrational complications.

22.♖xc4

The emergence of the ♗b2 and the transfer of the theatre of operations to the kingside emphasises the distance of the black pieces from their king. I was sure that this dynamic decision was the natural one and answered to the logical requirements of the position, and went in for the following sacrifices in defiance of the recommendations of the computer.

22…dxc4 23.♖xc4 ♕b7!

A precise reply. The black bishop will manage to occupy a good defensive post on f8.

24.d5 ♗f8

Black collapses after 24…cxd5? 25.♖g4 ♗f8 26.♗xg7 ♗xg7 27.♘h5.

25.♖h4 h6

26.♗xg7!

Here time is more valuable than a bishop! The tame 26.♗c3 would allow Black to bring his queenside pieces into the game. Furthermore, if the white bishop is not sacrificed on g7, then it is practically useless for the attack.

This idea was suggested to me by Kasparov’s notes to the following famous game:

Garry Kasparov

Lajos Portisch

Niksic 1983

‘At this moment I had a think. White’s pieces stand ideally, but nothing concrete is apparent. I felt that it was important to play actively, but how? It is tempting to play ♘f3-g5 or ♘f3-e5. However, on g5, the knight does nothing. 21.♘e5 looks good, but then the bishop on b2 is doing nothing. But what if we sacrifice it? Yes, sacrifice it!

21.♗xg7!! ♔xg7 22.♘e5

A surprising thing – White has no direct threats and he is a piece down, but he stands superbly! However, there is an explanation for this – the black knight is completely out of the game on a5…’

(G.Kasparov).

To complete the picture, we will give the rest of the game:

22…♖fd8 23.♕g4+ ♔f8 24.♕f5 f6 25.♘d7+ ♖xd7 26.♖xd7 ♕c5 27.♕h7 ♖c7 28.♕h8+ ♔f7 29.♖d3 ♘c4 30.♖fd1 ♘e5 31.♕h7+ ♔e6 32.♕g8+ ♔f5 33.g4+ ♔f4 34.♖d4+ ♔f3 35.♕b3+, and Black resigned.

26…♗xg7 27.♘f5

I had studied this position prior to sacrificing the exchange. Black’s extra rook is slumbering on a8, whilst White is attacking the king with greatly superior forces. But the computer assesses the position as clearly better for Black, who has a wide choice of continuations, the combination not being forcing. In an over the board game, I would have headed for this position without any qualms, but given the possibility of computer defence, I needed additional comfort.

What was that? The fact that I myself also used the computer to help did not solve the problem, as the net of variations was too wide. But here I recalled a device which Mark Dvoretsky pointed out was used by Mikhail Tal. In deciding on an irrational sacrifice, the magician from Riga would convince himself by calculating a few spectacular variations (not necessarily always correct), where the attacking side triumphs, and which would give him confidence that the sacrifice will succeed in practice. I followed a similar path. Using the computer quickly (not giving it extensive time to think), I went through several lines and reached a satisfactory result, which convinced me of the correctness of the sacrifice.

Speaking of the concrete position before us, we can note first of all that the black king cannot flee the danger zone: 27…♔f8 28.♘xg7 ♔xg7 29.♕d4+ f6 30.♕g4+ ♔f8 31.♖xh6 ♕g7 32.♖g6 ♕f7 33.♕f5 ♔e7 34.d6+, and White wins.

However, Black does have at his disposal the solid defence 27…♖ab8 28.♖g4 ♕b1+ 29.♕xb1 ♖xb1+ 30.♔h2 ♔f8 31.♖xg7 cxd5, which would force his opponent to take a draw by repetition: 32.♖h7 ♔g8 33.♖g7+ ♔f8 34.♖h7=.

One might reasonably pose the question why White would take such risks to move from an equal position to another equal one, where Black can force an immediate draw with such a logical and sensible move as 27…♖ab8? Of course, I was under no illusions about the sacrifice, but I still felt it was the most logical way of revealing the resources contained in the position. The white pieces seem to spring into life and I felt I did not have the right to condemn them to a boring future, marking time.

27…♗f6

An illustration of the laws of combat, even with computers around the place! Being a rook up, with his opponent apparently having no immediate threats, Black decides to continue the fight.

28.♖g4+ ♔h8

If 28…♔f8? 29.♘xh6 cxd5 30.♕a3+ ♔e8 31.♕d6, White’s attack achieves its aim.

29.♘xh6

Planning to bring the queen over via d3-f5-h5.

29…♖ab8

In the variation 29…cxd5? 30.♕f5 ♕e7 31.♖g3 Black is defenceless against the threat of 32.♕h5.

30.♔h2 ♕d7 31.♕e4 cxd5

Black loses after 31…♕xd5? 32.♕f4 ♗g7 33.♖h4 etc.

32.♕f4 ♖b6

The extra rook finally comes into play and White must force a draw.

33.♘xf7+ ♕xf7 34.♖h4+ ♔g7 35.♕h6+ ♔g8 36.♖g4+ ♗g7 37.♕xb6 ♕c7+ 38.♕xc7 ♖xc7

White has three connected passed pawns for the piece in the endgame, but in this instance, it does not give him real winning chances.

39.♖a4 ♖c6 40.♖a5 d4 41.exd4 ♗xd4 42.f3 ♗c3 43.♖a4 a5 44.h4 ♗b4 ½-½

In summarising the results of the discussion above, I should like to wish the reader courageous creative play, not hampered by doubts or uncertainties over computers refuting your ideas. At the end of the day, to paraphrase Lasker’s well-known saying, chess is played by living people, not computers.

Let us go back once again to the game Kasparov-Topalov and imagine the game was played by two machines. Without a doubt, White would have seen the resource 24…♔b6, and so would not have sacrificed the rook, preferring instead 24.♘c6+. As a result, the game would have been an unremarkable draw and chess culture deprived of one of its greatest works of art.

Of course, I am not recommending that the reader deliberately play sub-optimal moves, but as Xavier Tartakower wittily pointed out, ‘real chess only arises as a result of real mistakes!’