A public park, Potters Fields in London.

How plants are grouped plays a major role in how they are seen and appreciated. It makes sense to start with what happens in nature, and then look at how plants have been grouped historically in gardens. Finally, we will consider the plant grouping systems which Piet Oudolf has used in his work since the mid-2000s.

NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS

When we look at a natural environment it is a snapshot in time. Come back ten years later and it could be very different. Despite the timeless feel to many natural environments, they are all in a state of constant change and flux – ecological science now tells us that there is no balance of nature, but only a constant ebb and flow of species. This is particularly true of the many environments we are familiar with which are not really natural but semi-natural, such as meadows, where an annual cut for hay prevents trees and shrubs from growing, or even prairies, many of which were historically maintained by the burning practiced by Native Americans. Such environments are inherently unstable, and only constant human input maintains their particular range of plant life.

A good place to start is with an observation experiment. Look at a meadow (or indeed grassland managed for pasture) or prairie, and then compare it with a garden planting of perennials. What are the differences?

GARDEN PLANTING |

MEADOW OR PRAIRIE |

Usually fewer than ten plants per square meter |

Hundreds of plants per square meter |

Usually one to five species per square meter |

Up to 50 species per square meter |

Individuals of a species often in groups |

Individuals of species present, usually intensely intermingled |

Almost all plant varieties present chosen for distinct aesthetic value |

Plant community usually composed of dominant species (usually grasses or grass-like plants) – these species act as a matrix, together with smaller numbers of other species |

Bare earth or ground-covering mulch often visible |

Bare earth almost never present |

We should point out here that meadows and prairies are maintained extensively – everything has to be treated as one, and there is no possibility of maintaining individual plants – whereas in a conventional garden or landscape planting, individuals are often treated differently. Thinking about these differences purely in design terms, what are the implications?

Clearly, there are advantages and disadvantages to the look of the meadow/prairie. Traditionally, garden design has largely disregarded the meadow as a garden feature, but more recent thinking has made many of us more aware of some of its aesthetic advantages. It is these which have encouraged a new generation of gardeners and designers to reconsider the more diffuse beauty of the meadow and other grasslands.

Meadows and prairies are among many types of habitat where one species – or more usually one category – dominates, often grasses or grass-like plants, but with a large number of other species present in much smaller numbers. The whole forms a rich community, but in looking at it most of us tend to notice the highly visual minority element (the flowering perennials and occasional shrubs) rather than the dominant matrix of grasses which appear as a background. These type of habitats are actually very complex, with many species distributed through space with a high level of intermingling.

Thinking of other natural environments, what other types of plant grouping are there? At the opposite extreme to the meadow look are environments where one species appears to almost completely dominate. A good example is marshland colonized by reed (Phalaris arundinacea) or reedmace (cattails in North America, Typha latifolia), which are almost as much a monoculture as a field of maize or wheat. Between them are situations where plants form distinct patches, often intermingled with smaller species, for example in heathland with species of heather such as Calluna vulgaris and bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus).

Astilbe ‘Visions in Pink’ is part of an intermingled plant mix on New York City’s High Line. Repetition in a matrix of other plants evokes the repetition of plants in wild habitats.

PLANT GROUPING IN GARDEN HISTORY

During the nineteenth century summer bedding plants were grown in complex, often geometric and regular, patterns. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries this style began to be applied to perennials as well, with the development of a style where plants were grown intermingled in strips, with each strip being repeated at regular intervals. Nowadays this is very rarely seen done with perennials, although it has been revived in France and Germany for temporary summer plantings dominated by annuals.

Planting in groups of a mass of individuals of the same species or cultivar dominated planting in the twentieth century – we shall refer to this as block planting. The British designer Gertrude Jekyll promoted the use of elongated blocks, called drifts, which had the effect of changing the way plants were seen as the viewer walked along. The Brazilian Roberto Burle Marx, an artist by training, ‘painted’ with plants on a vast and dramatic scale, juxtaposing large blocks of strongly contrasting plants. Somewhat influenced by him have been the American partnership of James van Sweden and Wolfgang Oehme, who have also made effective use of large single-species blocks. For much of the century, however, block planting of a rather unquestioning and often lacklustre kind held sway, with countless landscape projects setting out plants, both perennials and small shrubs, in similar-sized blocks. Even in private gardens, block planting – at least where space allowed – held sway.

With the rise in interest in naturalistic planting, two developments have arisen which aim at a more thorough detailing of plant groupings. One is the randomization approach, which is derived from the almost-random effect of sowing a wildflower meadow from seed. The other is the work of the German researchers Richard Hansen and Friedrich Stahl, who from the 1960s onwards developed a highly structured approach which aimed at a stylized representation of natural plant communities. Hansen and Stahl recognized five categories based on structural interest and level of grouping: theme plants, companion plants, solitary plants, ground-cover plants and scatter plants.

The selection of plants for Piet Oudolf’s planting style has similarities to the Hansen and Stahl style. In particular, both he and they recommend that plantings comprise about 70 percent structural plants (those which maintain distinct visual structure for most of the growing season) and 30 percent filler plants (often rather formless, grown mostly for early season color). The Hansen and Stahl approach is extremely useful, but is in danger of becoming formulaic. What is distinctive about the Oudolf design style is its constant evolution, at the core of which is now the intermingling of plant varieties.

A reaction against single-species block planting began around the end of the twentieth century. The movement toward planting for biodiversity was expressed through a growing interest in sowing wildflower mixes and in ecology more generally. In the UK, Netherlands and Germany more sophisticated and naturalistic approaches to putting perennials together were established. When we talk about breaking the rules, the rule that individuals of each variety have to be clumped together in blocks is the first one to be broken.

WOODY PLANTS

Conventional planting has relied very heavily on woody plants – not surprisingly, since they make a major impact on the landscape and the majority are very long-lived. In conjunction with perennials, they will inevitably change the growing conditions beneath them, making the ground layer suitable only for shade-tolerant species. The mixed border, beloved by British amateur gardeners, is a small-scale example of the possibilities for combining shrubs and perennials (and indeed also annuals, bulbs and climbers), but given its scale, and the fact that these borders are often against a backdrop, it does often rather mean that the shrubs dominate – visually and ecologically. Larger scale and visually more innovative combinations of shrubs or small trees and perennials may allow more space for perennials.

One simple innovation which can make a great impact on many different scales is the shaping of hedges. Instead of cutting hedges straight, the individual plants in them can be given curves, so that each one stands out as an individual. This works particularly well with mixed hedges, where the individuality given to the plant by its own cut is reinforced by its size relative to the others and its characteristic foliage color and texture. Hedges cut like this help to merge it, and the garden it contains, into wider rural landscapes, or indeed any landscape where trees are part of the wider view.

The ability of woody plants to regenerate from cutting lies on a gradient, at one end of which there is no ability to regenerate from cutting back to the base, and at the other a strong tendency to produce suckers without any cutting back of the main trunk.

Large shrubs can be kept to a reasonable size by occasional cutting back to the base (coppicing). Frequent cutting back stimulates suckering, which can create an interesting effect. This technique can be applied to some familiar plants such as Cotinus coggygria (shown here) and the staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) to limit their height and encourage suckers. It is, however, easy to pull out and keep the forest down to a small colony of variously sized individuals. It is used on the High Line, and since this plant is so familiar to semi-natural woodland-edge habitats, including North American highway verges, its appearance can be a very effective way of saying ‘natural’, even two stories up in New York City.

Trees and shrubs vary widely in their ability to regenerate, which has implications for their management and their design use. Cutting a tree down, for example, may not be the end of the tree; this will kill nearly all conifers, but most deciduous trees will grow back with multiple shoots, a technique which is made use of in the traditional woodland management technique of coppicing. Many shrubs regenerate themselves constantly from the base – as old stems become senescent and deteriorate, vigorous young shoots emerge, growing straight up and eventually replacing the previous generations. The result is often a formless and tangled mass, but cutting back to base will result in a cleaner, more upright shape developing.

Some woody plants can spread through underground runners like many perennials, an example being the North American bottlebrush buckeye (Aesculus parviflora), forming large clumps. Species of Rhus are notorious among gardeners for suckering, but only after a period of existing as a deceptively tame-looking single-trunk tree. By cutting back every year or every other year, Rhus can be kept relatively small, sending up odd suckering shoots and creating the impression of a woodland-edge habitat with young trees merging with perennials and ground-covering plants.

A HIERARCHY OF PLANTING: PRIMARY PLANTS, MATRIX PLANTS AND SCATTER PLANTS

Take a quick look at a wild plant community such as a meadow, and you soon realize that you are not really seeing the plants. Our eyes tend first of all to be drawn to brightly colored flowers, and then to strong structures. The longer we look the more we see: more subtle colors, interesting shapes, juxtapositions and combinations. Repetition of key elements makes a big impact, with low-key features more likely to break through into our consciousness if they are extensively repeated – who notices a single white daisy in a field? But if it is re- peated 100,000 times, then it will dominate all else. There is a good case for recognizing the importance of ‘immediate impact’ species in a planting – those which stand out and make the most impact.

Still looking at our wild plant community in early to mid-summer, if we try to disregard the most obvious plants, what else is there? There are quietly colored species, often with cream or buff flowers, and of course plants which do not have either strong colors or distinct structures, such as grasses. Finally, there is the inevitable fact that the vast majority of what we are looking at is foliage: green, undistinguished, background.

Compare a natural plant community with a garden planting. The latter is almost inevitably going to have more concentrated visual impact. But how much more? And how is this visual impact distributed, and what relationship does it have to its background? On looking at the design of gardens down the ages (excluding parks or wider landscapes), it would appear that there has been a long-term trend from high visual intensity to lower intensity, but also a more graduated range of impact on the eye. Modern recreations of Victorian bedding schemes can leave some onlookers with a headache: so many colors, so much going on, everything there for impact, with a consequent rapid onset of visual exhaustion. The perennial borders which followed them in the early twentieth century were also packed with intense colors and striking juxtapositions. As the century progressed, some gardeners began to try to promote plants which were more subtle: in Germany Karl Foerster (1874–1940) began to use grasses and ferns, while in England the artist Cedric Morris (1889–1982) surprised visitors to his garden with his wide range of ‘unconventional’ plants. One of Morris’s circle was the young Beth Chatto (born 1923), who in the 1960s puzzled some in the gardening establishment and inspired others with her choice of plants, chosen for form and line and natural elegance rather than eye-grabbing color: creamy astrantias, green euphorbias and broad-leaved brunneras.

Contemporary tastes in planting owe much to pioneers such as Chatto, but also to those who have promoted the creation of natural or semi-natural habitats as beautiful and worthwhile garden features: wildflower meadows, prairies and informal country hedgerows. Now, very much under the influence of the wildflower enthusiasts, gardeners and designers are more open to plantings where higher impact plants are set in a matrix of lower impact ones – just as the wildflowers in a meadow are only a small proportion of what is actually dominant: the grass matrix.

It is useful to think about a hierarchy of plants in terms of impact.

Primary plants are those which have the bulk of the impact – in conventional plantings all the plants can be considered as primary plants, although among them there will also be a clear hierarchy of impact. In a traditional English-style border, for example, there will be high-impact plants chosen for strong colors or structure being played off against lower impact ones such as pale lime-green Alchemilla mollis. For those new style plantings where higher impact plants are contrasted against a backdrop of lower impact ones, we will use the term ‘matrix plants’ for these quieter elements.

Matrix planting is where one or a limited number of plant species is used en masse, within which are embedded individuals or small to medium size groups of other, usually more visually prominent species.

A good analogy for the primary plant/matrix plant relationship is with a fruitcake, where nuts and fruit are scattered through a dough matrix. Having primary plants distributed through a matrix of others with lesser visual impact creates a more naturalistic and less obviously deliberate effect. It recalls, even if only psychologically, the visual feel of wild habitats, where a large mass of low-impact plants are studded with stronger impact clumps or individuals.

Scatter plants are often most effectively added to a planting by literally randomly scattering them, for their role is primarily that of adding a sense of naturalness and spontaneity, and by being scattered throughout the whole, a sense of visual unity.

So, now we will look in more detail at what role plants in these categories might play in planting design and what kind of plants might be used. Unless specified, all schemes are Piet Oudolf’s.

PRIMARY PLANTS – GROUPS

For many years, planting design on any scale larger than that of a domestic border involved putting plants in groups. These might be as small as three or involve blocks of hundreds of plants – the key point being that the group is a monoculture of one species or cultivar. There are some advantages to using single-variety groups of perennials, but these only really apply to larger public plantings and not to private gardens. One is that it simplifies maintenance where staff are unskilled and cannot be adequately supervised. Another is that it allows the clear expression of leaf textures which can get lost in more diffuse plantings.

In public spaces there is also an educational reason for block planting; there is no doubting the role of parks and public gardens with a wide variety of perennials in inspiring the public to be more adventurous in using them in their own gardens, particularly in regions where there is little history of using perennials. In order to inspire people, they need to be shown how plants look, which is most easily achieved with single-variety groups. The impact of the plant’s color and form can be seen right away, without viewers having to work out which flower belongs to which bit of foliage or how it relates to the ground beneath it. The character of a plant, that indefinable sum of habit, foliage form and flower color, can often only be really appreciated when it is grown in a single-species block – though if it is rangy or has unattractively sprawling stems when it looks at its best, then perhaps it would do better intertwined more naturalistically with its neighbors. Educational – but disadvantageous for the overall effect – can be the untidy or unattractive appearance of certain plants after flowering, or when under stress or pest or disease attack. Group planting can throw a harsh spotlight on to a plant’s character and point to its shortcomings.

Group-based planting can be made a lot more interesting in several ways:

The last method is the most radical as it challenges the dogma of the monocultural block, and is the first, albeit cautious, step toward the idea of mixed plantings.

Just as in all but the smallest domestic gardens repetition provides a sense of rhythm and unity, in large-scale plantings which use more or less equal-sized groups there is also a need for clear repetition. Without repetition, group-based plantings lack a sense of unity. Just as a domestic garden with one of everything becomes a botanical collection – or ‘plantsman’s garden’ in the polite terminology of British guides to gardens open to the public – so does a larger planting offering nothing but chunks of disparate plants. Repeated groups work best if made up of species with very good structure over a long time, or a long flowering season combined with a reasonably good appearance when no longer in flower. Taking the Trentham planting as an example (see opposite), there would appear to be a bewildering number of varieties – there are around 120 – but since many of these are very closely related, the number of truly distinctive plants is more like 70.

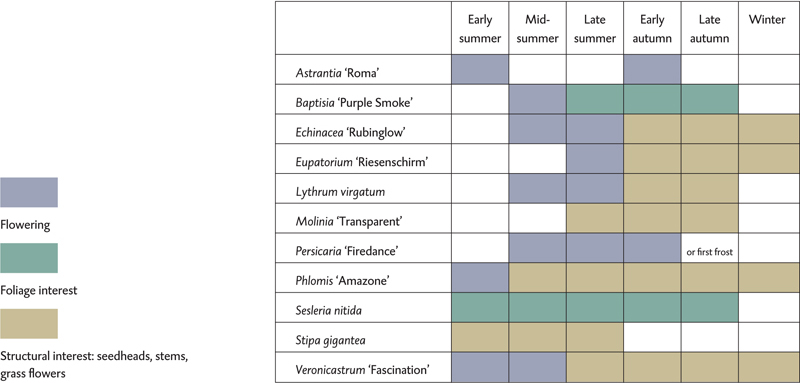

The eleven most frequently used plants in the ‘Floral Labyrinth’ at Trentham (see the table opposite) illustrate the value of repeating species with a long season of interest, and the importance of looking beyond flowering as the only or even main source of interest.

Here, in August at Pensthorpe Nature Reserve in Norfolk (1996), the impact is created by groups of plants where multiple individuals of a variety are clumped. The red is Helenium ‘Rubinzwerg’. Several pale pink Persiciaria amplexicaulis ‘Rosea’ also make an impact.

Taken when part of the Oudolf garden in the Netherlands was run as a nursery, this photograph illustrates very clearly two approaches to structural planting. One is the formal arrangement of geometric clipped shapes – in this case Pyrus salicifolia ‘Pendula’ (silver pear) – and the other is the scattering of grass Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’. The grass with its long season of interest can be distributed in plantings in many different ways, all to great effect. Here it can be regarded as a random scatter element. The small tree in the foreground is Rhus typhina, which is coppiced every few years to limit its size.

Small clumps of purple Stachys officinalis ‘Hummelo’ make a dramatic splash against pale green Sesleria autumnalis, which is here used as a matrix plant on the High Line in New York in July. Note how the stachys is repeated.

The ‘Floral Labyrinth’ at Trentham, Staffordshire (2004–7). This planting, in the grounds of what was a major country house garden and is now a visitor destination in the English Midlands, occupies an area around 120 meters long and 50 meters wide, including wide grass paths and two central grass areas. It has an interesting place in the development of the Oudolf planting style, as it is based overwhelmingly on the equal-sized groups which he used in previous large projects, such as Pensthorpe Nature Reserve in Norfolk (1996) and Dream Park in Enköping, Sweden (2003), but includes some hints of the levels of added complexity which he started to develop in projects which came later.

The overwhelming preponderance of grouped perennials is broken up a little by a few groups being mixtures, such as Lythrum virgatum with Liatris spicata (both deep pink narrow spikes) – shown on this plan section. Not visible on this comparatively small excerpt are also some small groups of repeating plants scattered through, such as Baptisia ‘Purple Smoke’ (very good bushy structure from May to October) and Astrantia major ‘Roma’ (long season of pink flowers).

Seasonal Interest of the ‘Floral Labyrinth’ at Trentham

Block planting at Trentham in the context of a historic landscape (the Cedar of Lebanon, Cedrus libani, would date to the eighteenth or early nineteenth century). Now, in September, the definition of grouped plants is partly lost and the area takes on a wilder look. The orange is Helenium ‘Rubinzwerg’, while the grass on the right is Molinea ‘Transparent’. The odd dark ‘dreadlocked’ seedheads in the right foreground are Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Fascination’.

A large park such as Trentham planted in a very informal way with blocks of perennials in large beds among which it is possible to meander has a very definite similarity to what can be used on a smaller scale in the domestic garden with single plants or small groups. The principles are exactly the same. There should be a feeling of fluency so that as you walk through you are presented with not only variety (lots of different plants) but also the sense of familiarity which builds up when plants are repeated. Repetition can be regular, but in very informal plantings this has little meaning, so aiming for the random look is often better. Random repetition often works subliminally, so that as you walk around, the same species is seen again and again, not so often as to be obvious but often enough for it to work its way into the subconscious.

Repetition, of either individuals or blocks, works very differently as the year progresses. Early on, in spring or early summer when hardly any perennials are above half a meter high, repetition effects are obvious because everything is seen at once, and indeed are vital if the garden is not to seem disparate and messy. Later on at the height of summer and beyond, as perennial growth gets taller, the clarity of repetition becomes much less obvious. If growth is so high that the exploration of a planting becomes a journey through rather than a look over, with vision restricted to what is growing immediately around, the experience becomes very different. Repetition will be appreciated by seeing the same plant or perhaps the same combination – in other words, it is appreciated as a function of repetition in time not repetition in space, and is more likely to be perceived subconsciously.

PRIMARY PLANTS – DRIFTS

Favored by Gertrude Jekyll, the drift is an easy way out of the dangers of the monotony which overreliance on block planting risks. Drifts are long and thin, and can be winding and snaking, so bringing different plants into close proximity. Often, given the tendency of many perennials to sprawl, trail and weave, there will be an impression of intermingling. More basically, however, the shape of the drift inevitably means that groups of plants will be seen differently from head-on to side-on, so there will be a sense of development as the viewer walks by. Jekyll’s drifts were designed for the wide rectangular borders favored by early twentieth-century British garden architects.

An advancement on drifts is the use of simple combinations of up to five or six varieties in a large drift. This was used extensively in the double borders at the RHS Wisley garden in Surrey in 2001, where each drift was exactly the same size and rigidly geometric. The reality on the ground is that plant foliage spills over the straight edges, and given that each drift is a mixture, there is no sense of regimentation.

Drifts offer a good midway format for gardeners and designers who want to break away from traditional block plantings but feel that they do not have the experience to attempt more complex mixed plantings. Drifts can create an illusion of intermingling, and they have certain advantages for ongoing management above mixed plantings. If there are plants which need a mid-season tidy-up or pruning, it is easier to gain access to them as well as to carry out additional planting – for example of bulbs, which are notoriously difficult to add to existing perennial plantings. Perhaps most importantly, by keeping the complexity low and relatively predictable, it is easier for maintenance staff with low plant knowledge to weed and manage the planting.

At Trentham, two cultivars of grass Molinia caerulea are used to create what is essentially a matrix, into which are embedded perennials and some small shrubs. The grasses very much dominate, however, so the overall effect is that of a stylized meadow. What is important to stress here is that the two Molinia cultivars used (‘Heidebraut’ and ‘Edith Dudszus’) are both planted in monocultural blocks, but in the form of complex drifts. If the two varieties had simply been mixed together the effect would have been a blur, as they are too similar to be easily distinguished. Planted as separate drifts, the distinction between the two can be appreciated, but the drift effect melds and intertwines them in a way which evokes the subtle patterns of grasses in natural grasslands.

The rivers of grass at Trentham in early June with cultivars of Iris sibirica in flower among Molinia caerulea ‘Heidebraut’ and M. c. subsp. caerulea ‘Edith Dudszus’. Some yellow Trollius europaeus and pale pink Persicaria bistorta are also visible – all are tolerant of the occasional flooding which affects this area.

Rectangular drift planting at the Royal Horticultural Society garden at Wisley in Surrey (2001) uses strips of plant combinations of between four and six varieties seen long end on to viewers as they walk down a central grass aisle. The geometry of the plan is invisible beneath vigorous, intermingled plant growth. Here deep blue spikes of Agastache ‘Blue Fortune’ are intermingled with white Eryngium yuccifolium; in the background purple Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Fascination’ is visible in another strip. The shrub to the right is Cotinus coggygria with its distinctive seedheads.

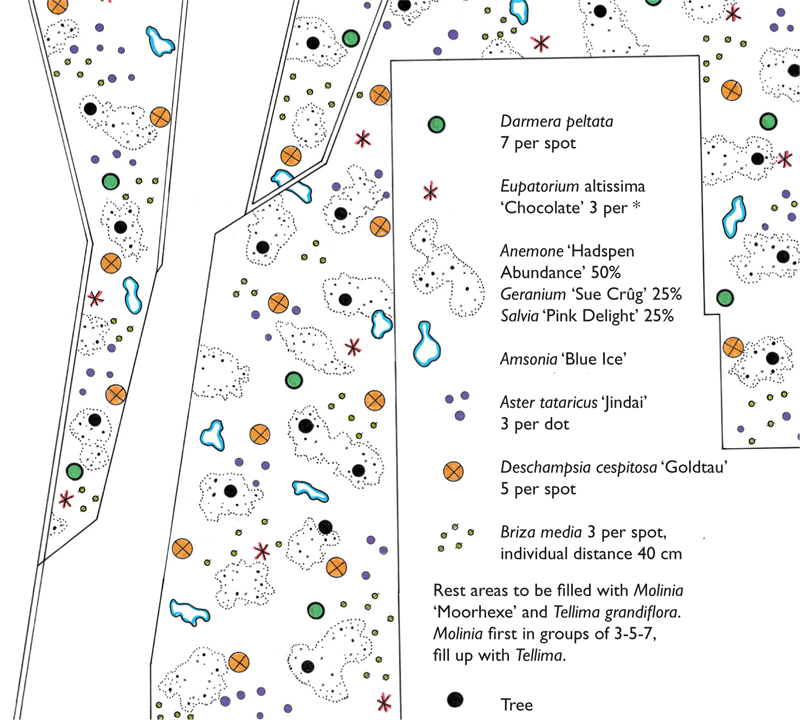

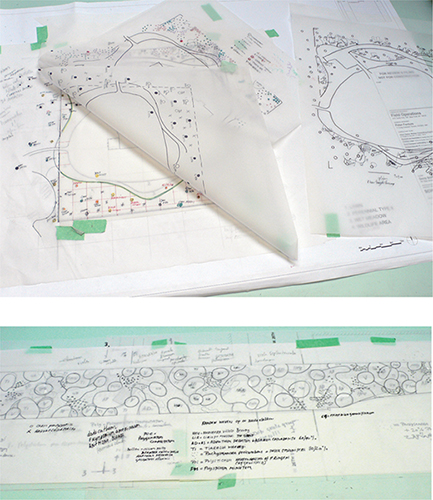

A detail from the plan for Potters Fields Park, London (2007), where jagged drifts are an effective way of creating simple mixed planting combinations.

At Potters Fields Park, London (2007), drifts of grass and perennial combinations create an orderly but dynamic effect. In the foreground is a mix of Echinacea purpurea and white-flowered, sprawling Calamintha nepeta subsp. nepeta. The grass in the background is Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’.

A drift of Sesleria autumnalis in the foreground with red Helenium ‘Moerheim Beauty’ and Deschampsia behind. Other perennials are also included in each drift, but are not visible here. The use of drifts in this park creates a strong sense of movement and maximizes the trade-off between relatively simple, easy-to-maintain planting and visual complexity.

REPEATING PLANTS

Repeating plants can be used individually or in small groups at – very generally – regular intervals to add rhythm and variation to block plantings and to generally break up their chunkiness. Fundamentally they are about creating a sense of unity; whether in a private garden or a large public space, the repetition of a few distinct long-season plants creates a feeling that ‘this is one place, with one design and one vision’. They can be used to lead the eye and so direct the viewer.

On a smaller scale, one particular area can be given a sense of unity with repeating plants, and in this case it will be more about stamping a distinct personality on that area with respect to the rest of the garden. An example of both these uses of repeating plants can be seen in the plans for Leuvehoofd (see pages 107–109).

A shaded area from the van Veggel garden, Netherlands (2011), the large pencil arcs representing tree canopies. This excerpt from a much larger plan illustrates group planting of shade-tolerant plants interspersed with repeating plants. The key below (left) is for the repeating plants. Numbers for the repeating plants are given for each mark, with an additional annotation for Thalictrum delavayi ‘Album’ that they be scattered. All the repeating plants used are quite solid clump-formers, with the Thalictrum being an exception. Its tall stems and fluffy flower-heads are relatively insubstantial, and so small groups of it need to be repeated in order to make much of an impact. Note the wavy edges to the blocks – this blurs the boundaries between plant groups.

A public planting for the Westerkade – the old quayside of the river Maas in Rotterdam, where beds of varying size run for several hundred meters. There are two planting combinations. One is around the canopy of some existing elm trees and uses small ornamental trees and shrubs such as varieties of viburnum and hydrangea and perennial underplanting for foliage interest. The other is for the more open areas and uses a matrix of a molinia grass and a limited range of perennials. Of these, the tall, self-seeding umbellifer Peucedanum verticillare, was intended to provide an element of the unpredictable as well as an imposing winter sight. There were, however, not enough Peucedanum so some of the smaller, dark-flowered Angelica gigas were also used.

Good repeating plants need to have a distinct personality and a long season of interest, or at least disappear tidily or die back discretely, as seen in the plan from the van Veggel garden in the Netherlands on the previous pages:

At the Maximilianpark in Germany, groups of roughly similar size are interspersed with repeating plants, chosen for long-season color or structure interest or else late interest often preceded by attractive foliage. An exception might be Geranium psilostemon, which like all geraniums has poor structure and can look untidy after flowering, although it disappears among taller planting later in the season. It is, however, valuable for its vibrantly colored flowers in early summer, which have a great capacity to seize the attention and so stamp a unifying personality on a planting. It is interesting to look at the numbers of the repeating plant species in the plan. There are twice as many groups of the species which are used the most – that is, certain plants are used to visually dominate. These include two grasses (Molinia ‘Transparent’ and Panicum ‘Shenandoah’) – structural but at the same time relatively low-key – and Aster tartaricus ‘Jindai’, a late, bright variety with an upright and unusually neat structure for an aster. Among the repeating plants with the lowest level of appearance are a number (such as Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Orange Field’ and Inula magnifica ‘Sonnestrahl’) which are physically large and bulky – not many are needed to make an impact.

The numbers of the repeating plants used are as follows (see the table below):

Seasonal Interest at the Maximilianpark, Germany

Yellow Rudbeckia subtomentosa is repeated along a stretch of the High Line, set in a matrix of grasses, mostly Sporobolus heterolepis and Panicum ‘Shenandoah’, in August. This effect is remarkably similar to the grass-dominated and perennial flower-studded semi-natural habitat to be seen alongside many American highways and in prairie remnants.

The concept of matrix planting is one which has been around for some time, but like many terms in planting design it has had the unfortunate history of being used by different people to mean different things – in part because of a misunderstanding over the meaning of the word. ‘Matrix’ is defined in the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language as ‘a surrounding substance within which something else originates, develops, or is contained’, and it is with this in mind that we will use the term – we have already suggested the analogy of a fruitcake for describing a matrix.

The matrix evokes the situation in many natural habitats where a small number of species form the vast majority of the biomass, studded with a larger number of species present in much smaller numbers but which are a visually important element. Consequently, good matrix plants are visually quiet, with soft colors and without striking form. They also need to be effective in physically filling space – part of their function is to be a ground cover (or at least to hide the soil surface), so they need to mesh together well. It is vital that they always look good or at least acceptably tidy, so that even when they have finished their main season of interest they have good structure, do not flop over or look sad and bedraggled.

Grasses are the obvious plants to use for matrix planting, especially tussock-forming or bunch grasses (that is, cespitose species), or the denser and slower growing clump-forming species. For a variety of reasons to do with their physiological efficiency, grasses dominate most open temperate zone habitats. Researchers and practitioners like James Hitchmough and Cassian Schmidt have suggested that using cespitose grasses might be a good way to create low-maintenance plantings. Many such grasses are very long-lived and stable, with ‘closed nutrient cycles’: that is, they recycle nutrients from their old leaves as they fall down and rot around them. The environment they create is potentially a competitive one, which would have the desirable effect of reducing weed growth. Yet because they do not form runners and so create a complete canopy in the way that turf grasses or slowly spreading ones like Miscanthus or Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ do, they will not compete so strongly with flowering perennials that they risk eliminating them. Long-lived perennials or other species which have a similar form of growth may be considered as stable companions in the long term. Early Oudolf matrix-type plantings used Deschampsia cespitosa as the dominant grass; in cultivation on fertile soils it is relatively short-lived, but it can also self-sow strongly, so the chances of the long-term development being either no-Deschampsia or too-much-Deschampsia are all too likely. The good thing is that Deschampsia does appear to be compatible with a great many other plants – it does not totally out-compete them. Varieties of Molinia caerulea, a long-lived species, also offer the hope of greater stability, although the tight clumps of many cultivars of these plants leave a lot of bare soil between them and so are best in combination with low spreading or sprawling perennials such as varieties of Calamintha. Sporobolus heterolepis has great potential as it has the fuzzy charm of Deschampsia cespitosa and is an important natural matrix plant; in its native dry prairie it is known to live for decades; it is, however, slow to establish in cooler European climates.

The potential of Carex (sedges) and other plants which can substitute for grasses both ecologically (in that they naturally dominate) and visually (they have long narrow leaves) to act as matrix plants is enormous; there is a feeling that the surface has hardly been scratched with these long-lived, often evergreen, stress-tolerant and resilient plants. Other plant genera which offer similar evergreen possibilities include Luzula in cool, moist climates and Liriope and Ophiopogon in climates with warm, humid summers – the latter are commonly used in the south-east USA, much of eastern China and Japan. Behavior varies from the strongly spreading to the tight clump, so huge opportunities for gardeners and landscape designers exist here. All these plants together are commonly known as ‘grass-like plants’ – it is important to understand that although they may look like grasses, they are not; grasses have a different physiology and tend to be greedier for light and nutrients.

Other potential matrix plants include clump-forming species grown chiefly for their foliage, like varieties of Heuchera, Tellima, Epimedium or woodland species of Saxifraga. Plants such as these, or with similar semi-evergreen leaves and a spreading habit, often form a major component of the ground flora in woodland. Iris sibirica is possible as a lesser component in matrix planting – its flowering season is so short that its strap-like leaves make it function almost as a grass, it always looks tidy, is very long-lived and has good seedheads; a habit of crushing competitors with a dense thatch of slow-to-rot leaves does, however, mean that it can only be combined with equally robust plants or that a maintenance program specifies their removal.

Finally, there is the potential of certain late flowering perennials as minor components in a matrix. Limonium platyphyllum, those varieties of Sedum descended from S. spectabile or S. telephium, and several species of Eryngium (for example, E. bourgatii) are very long-lived, stress-tolerant – particularly of drought – and never look untidy. In Chicago’s Lurie Garden, the broad heads of Limonium platyphyllum, composed of thousands of tiny flowers, form a soft haze that other flowers blend and blur into, showing the potential of the visual aspect of the matrix.

One thing which needs to be borne in mind about the limited range of plants used in matrix-based plantings is that they are relatively stable in the sense that they continue to occupy the same space over long periods of time. This is true of many cespitose grasses, but also of flowering perennials like Sedum telephium varieties and Limonium platyphyllum. Iris sibirica and the low clump formers like Tellima do spread slowly, but they have a proven ability – in suitable conditions, of course – to dominate and hold space over long periods.

While the use of cespitose grasses, and sedges as well, is clearly an application of what is often seen in nature, the use of non-grass clump formers also has a natural model in that some woodland-floor habitats are dominated by these plants, at least where light and other conditions allow. Among clump-forming perennials, though, there is considerable variation in medium- to long-term performance, even between cultivars within the same genus. This is emphasized because of the importance of selecting plants which will do the functional ground-covering work demanded of them. In the case of Heuchera, for example, some cultivars do this well and others do not, becoming gappy after only a few years and frequently dying altogether.

Other possibilities for matrix planting are those lower growing species which run, and so make effective ground covers and fillers of space. Generally these are more suited to shaded or partially shaded habitats where grass growth is weak. Examples would be Phlox stolonifera and some lower growing and spreading ferns like Adiantum pedatum. A few species for open habitats, such as Euphorbia cyparissias, occur in nature as occasional shoots among a mass of grasses and other meadow components. In cultivation it rapidly fills in gaps between other plants which form denser clumps, but is readily out-competed by larger plants. However, recent research in Slovakia suggests that some species of Euphorbia and certain other plants may be allelopathic: they release toxic compounds which reduce the growth of other species around them.

Many gardeners and designers will be happy with keeping the matrix concept simple, so that there is only one limited plant combination which is randomized over a large area, to which other plants in smaller quantities are added. In a private garden or small space, this idea of the matrix as something which is uniform is probably important to keep to, as part of the concept of the matrix is its simplicity. However, nature is not like this! Walking through a botanically rich grassland habitat such as American prairie or central European meadow makes the observer aware of just how complex these places are; what appears at first to be a mass of uniform grass and perennials resolves itself into complicated patterns and constant change. The minor elements, the decorative perennials in particular, vary enormously in their distribution – this is obvious. But the majority (usually grass) components also often vary. Typically, a walk through a natural habitat reveals greater concentrations of one species in one area, transitioning to another area where another species assumes more importance.

In more extensive landscape plantings, greater interest and greater naturalistic effect might be achieved by not having an identical matrix spread over large areas. Nature’s tendency to grade one species into another can be imitated with transition effects. Also, large blocks can be planted up with different matrix species – what will be perceived here is one pattern overlaying another. The underlying matrix will be changing, but the perennials scattered across it, either as small clumps or individuals, will have another pattern linking across the underlying matrix groups.

A simple matrix planting at Bury Court, Hampshire, with Molinia caerulea forming a meadow-like mass in which Digitalis ferruginea, a short-lived but self-seeding foxglove, and Allium sphaerocephalon are flowering in July.

Sesleria autumnalis forms a matrix for Agastache ‘Blue Fortune’, Echinacea purpurea cultivars and, in the background, Veronicastrum virginicum. Sesleria grasses have the advantage of forming a weed-excluding mat but are not aggressive spreaders, while this particular species has a color which acts as a very effective foreground for flower colors. This is a garden in West Cork, Ireland, in July.

In late September on New York’s High Line, grass Calamagrostis brachytricha forms a matrix, while the seedheads of Achillea filipendulina ‘Parker’s Variety’ and the yellow flowers of Coreopsis verticillata add touches of color and definition.

MATRIX AND REPEATING PLANTS

A design based on a matrix is essentially a two-stage planting: one is the larger areas of less visually dominating plants and the other is more the visually dominant elements, what we have so far been calling primary plants. The more visually dominant elements are most effective if they too are repeated. A matrix is a filler, a backdrop, which – whatever visual merit it may have on its own – is about throwing the primary plants into a higher relief and emphasizing their special values. I might argue, too, that making a clear distinction between the primary plants and matrix plants creates more diversity of visual interest than having a purely random distribution of all the elements, as might be seen in meadows or plantings which seek to imitate them. To continue with the fruitcake analogy, part of the pleasure of eating fruitcake relies on the distinction between the fruit and the surrounding cake.

The purest and most natural form of matrix planting is simply to create a grass meadow and repeat a limited number of perennials across it. By using cespitose grasses, the planting at least has the chance of achieving a compromise between long-term survival (most likely because of the presence of the grasses) and ornamental effect (the flowering perennials).

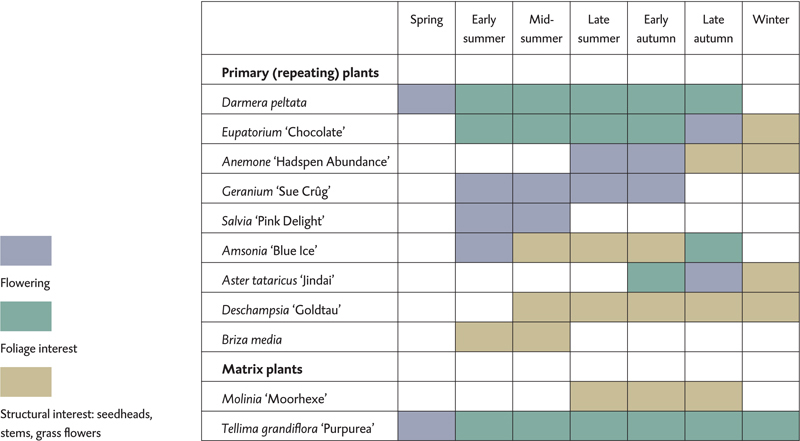

Extract of a plan for Ichtushof, a project for Rotterdam City Council in the Netherlands (2011). This is a site where office buildings create a northerly aspect. Young multistem specimens of the river birch Betula nigra ‘Heritage’ are indicated by black dots. As young trees they will exert little root pressure on surrounding perennial planting, and in any case they cast relatively light shade. However, in time it is envisaged that some perennial species will be lost. Note that shade and tree-root tolerant plants are intermingled in groups around tree bases. The planting takes the form of a clearly functional, but not very natural, matrix of Molinia ‘Moorhexe’ and Tellima grandiflora ‘Purpurea’ with small groups of repeating primary plants. Species used are indicated in the table opposite.

The table below shows the distribution of interest throughout the year for matrix and primary plants for the area of the Ichtushof planting. It is worth noting that Darmera and Amsonia have good autumn foliage color – relatively unusual among perennials.

In the Ichtushof planting shown, the matrix is made up of grass Molinia caerulea ‘Moorhexe’ and perennial Tellima grandiflora ‘Purpurea’, laid out in the following ratio per square meter:

Tellima is a low, clump-forming, semi-evergreen perennial which acts as an infill between the upright Molinia foliage to minimize the amount of bare soil. The primary plants are, for the most part, in small groups, repeated at relatively regular intervals over the site. This planting also illustrates the importance of the order in which plants are placed:

Seasonal Interest of the Ichtushof planting

An extract from a plan for the van Veggel garden in the Netherlands (2011). A matrix with repeating primary plants for a sunny situation. The matrix is made up of Sporobolus heterolepis (65 percent), Echinacea purpurea ‘Virgin’ (25 percent) and Eryngium alpinum (10 percent).

The table above lists the primary and matrix plants used in the area shown in the van Veggel garden.

COMBINING MATRIX AND BLOCK PLANTING

Combining matrix and more conventional block planting effectively contrasts these two different approaches to perennial planting. The discipline needed to restrict the numbers of varieties necessary for matrix mixes to work is perhaps too tight for many locations, where a wide variety of plants are needed to engage the onlooker. There is also the fact that matrix planting, being a kind of mass planting, is particularly dependent for its success on the plants used flourishing and growing on the site chosen. Failures on such a large scale cannot be risked, so there will be an inevitable tendency to rely on tried and tested varieties – arguably this limits innovation and the creation of a sense of novelty. Combining the mass effect of matrix planting with blocks enables a compromise, with plants less well understood by the gardener or designer being used in small groups. Blocks also allow for plants which need specific cultural care: it is not very practical to wade into a matrix planting to cut back all the specimens of a particular variety. A group of one variety, however, can be easily dealt with, useful for tidying up those which have a ‘bad hair day’ after flowering or which benefit from mid-season pruning.

Contrasting blocks with a grass or grass-like matrix is essentially about combining a classic form of planting with a blend of plants which most onlookers would read as a meadow. The old and conventional and the new and naturalistic are brought together, and the contrast can be striking and informative. The design can also be driven by a simple artistic conception of contrasting different plant qualities. Viewers are confronted with the possibility of breaking into new ways of planting and reminded that plants do not naturally grow in orderly blocks. A similar effect can, of course, also be achieved by having borders of grouped plants adjacent to a sown wildflower meadow or prairie.

Perennials

Acaena species and cultivars

Asarum europaeum

Asperula odorata (Galium odoratum)

Calamintha nepeta subsp. nepeta

Campanula glomerata

Coreopsis verticillata

Epimedium species and cultivars

Euphorbia amygdaloides

Euphorbia cyparissias

Geranium nodosum

Geranium sanguineum and cultivars

Geranium soboliferum

Geranium wallichianum

Heuchera species and cultivars

Iris sibirica

Lamium maculatum

Liriope species and related genera such as Ophiopogon, Reineckia

Limonium platyphyllum

Origanum species and cultivars

Phlox stolonifera and other procumbent Phlox

Salvia ×superba, S. nemorosa, S. ×sylvestris

Saponaria lempergii ‘Max Frei’

Saxifraga, clump-forming woodland species

Sedum ‘Bertram Anderson’ and other low-growing sedums

Stachys byzantina

Tellima grandiflora

Grasses and grass-like plants

Carex bromoides

Carex pensylvanica, many other potential Carex

Deschampsia cespitosa

Hakonechloa macra

Luzula species

Molinia caerulea, smaller varieties

Nassella tenuissima (syn.Stipa tenuissima)

Schizachyrium scoparium

Sesleria species

Sporobolus heterolepsis

Ferns

Adiantum pedatum

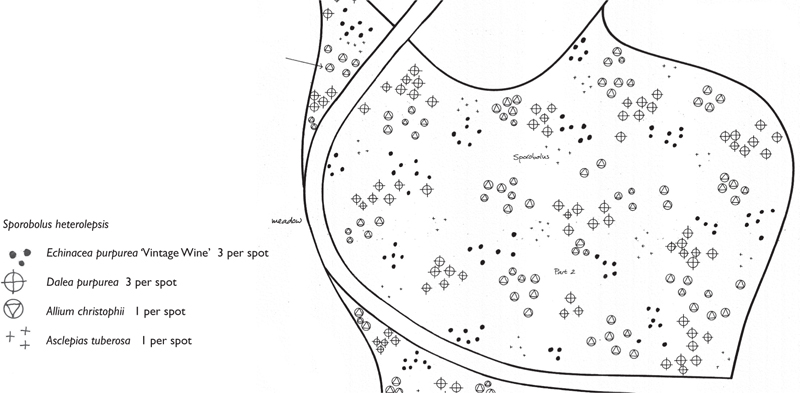

A plan for a meadow of Sporobolus heterolepis in a garden on Nantucket, Massachusetts (2007 onwards), with loosely grouped repeating plants: the Allium christophii for late spring/early summer and the others for mid-summer interest. As plants of sandy and dry prairie soils, the Dalea purpurea and the Asclepias tuberosa would be natural companions for Sporobolus.

Leuvehoofd, Rotterdam, Netherlands, is a recent example of public planting (2009) using grouping of perennials, matrix planting and repetition. A central unifying stripe of grass Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldschleier’ creates a striking impression. The more complex arrangement of perennials in groups creates sustained interest.

In this example, the Deschampsia matrix includes a high proportion of Sedum telephium ‘Sunkissed’ and occasional plants of Limonium platyphyllum. There are also some repeating plants for added late season color and dark seedheads (for example, Helenium ‘Moerheim Beauty’) and Molinia caerulea (a late season grass, an upright contrast with the mounding of the Deschampsia). Crucially, these last two repeating plants are used throughout the rest of the planting, tying the whole together for the time that they are performing. Two other repeating plants are also used here, but they are only in the outer group-planted areas: Festuca mairei (a medium-sized and incredibly resilient grass with a long flower/seedhead season) and Agastache foeniculum (an upright mid-summer flowering perennial with good seedheads).

Plan for a planting on the waterfront at Leuvehoofd (2009), using a combination of matrix and group planting. The plan shows six beds of a dramatic shape; the masterplan was developed by the city landscape architects. Three different planting treatments are used:

Matrix and group planting plan. Here, in the Nantucket garden, an area of meadow-like matrix in the middle contrasts with plant groups around the edge. The matrix planting is essentially Eragrostis spectabilis with Molinia ‘Moorhexe’ and Anaphalis margaritacea, and loose groups of a number of other species represented by symbols (right).

Species which appear more or less at random through a planting can be termed scatter plants. They are added as individuals, not even in loose groups, and create a feeling of spontaneity and naturalness. They can be randomly scattered into groups of other species, including matrix mixes, the key aspect being to repeat them to create a sense of natural rhythm.

This technique is useful for a variety of plant forms which enhance a planting through a seasonal splash of color or a long period of distinct structure – the point is that they must be distinctively different to the rest of the planting. On a large scale, even something as bulky as Baptisia alba subsp. macrophylla could be a scatter plant. This is actually a good one, as once its white flowers have faded, its foliage texture, shrubby shape and tough, dark seedpods give it character and distinctiveness. On a smaller scale, the best species are often those which are physically slight, so that when they are not in flower are hardly noticeable. A good example for a smaller planting would be Dianthus carthusianorum, whose bright pink flowers have a visibility out of all proportion to their size; they are produced at the end of rangy stems best left to trail through the more substantial clumps of other species. When not in flower this plant is virtually invisible.

LAYERING PLANTS – READING NATURE AND WRITING DESIGN

Looking at a natural environment can be a confusing experience. Whereas some plant communities are clear and graphic, or can be at certain times of year, others can appear as a tangled web – a mass of plants confronts the eye, and it can be difficult to work out what is going on. Understanding a plant community as layered can help a lot. Plants can be thought of occupying a limited number of physical layers within a community. Sometimes these layers are clearly segregated by eye and so visible, but at other times they are not and are more difficult to distinguish. In some cases the word ‘layer’ is more of a metaphor, but nevertheless it can be possible to read the confusion of leaves and stems in front of you.

Having understood the concept of layering in wild or semi-natural plant communities, it is possible to transfer it to designed plantings, both as a way of helping the gardener and designer structure space but also as a way of simplifying the planning, visualization and implementation of a planting.

Mature temperate zone forest is very clearly layered. Mature trees form a dense canopy, beneath which are understory trees and shrubs, usually much less dense. In North America and Asia, small trees or large shrubs such as Acer (maple), Cornus (dogwood) and Rhododendron occupy this zone, although their growth is often very thin and open compared with how they appear in cultivation. In Europe, examples which fill this layer are species of Ilex (holly) and Corylus (hazel). Below this is a ground layer, composed of herbaceous perennials, ferns and sometimes small-growing suckering shrubs, often evergreens such as Mahonia or Vaccinium. Below this are smaller perennials, mosses and fungi. Climbers – plants which root into the ground and use other plants for support – can be thought of as another layer: often a conceptual layer, as their visual role is often to blur and confuse the appearance of layering to the human eye.

In grasslands such as meadow or prairie there are also layers, but they are rarely distinguished as clear physical divisions. Grasses tend to dominate and form one layer; in prairie long-lived upright perennials such as Baptisia species form another. Subsidiary herbaceous flowering perennials are a minor but highly visible layer, along with perennials which tend to lean on others for support. European meadows include many in this latter category, such as species of Geranium and Knautia. Still others are herbaceous climbers such as the vetches, a varied group of plants in the pea family.

For design purposes, such complexities and ambiguities can be, and indeed often must be, swept away. Layering is about segregating plants so that the visual effect is clear and coherent and about clarifying the design process and simplifying setting out for planting. For planning purposes two or three layers are all that is needed, although these can potentially include several plant categories.

The New York High Line provides an example. One layer is missing here, of course – there are no large trees (otherwise the owners of apartments lining the track would have a lot to complain about). On parts of the High Line, there is a clear distinction between shrubs and a ground layer of grasses/sedges and perennials – here there are two layers. In other areas the planting is divided into layers which are conceptual rather than physical – a matrix layer and a layer of perennials in clumps or groups. Scattered plants can also be described as a third layer.

It is relatively straightforward to design a planting in layers using tracing paper; each can be looked at individually or all put together to get an overview. For implementation, each layer can be treated separately, which greatly simplifies the process of setting out plants.

The mind can easily visualize the layering technique applied to the underplanting of woody plants with a ground-cover layer of perennials, but less easily to grasses and perennials. Each layer tends to deal with the distribution of plants in a different way: one layer may be a simple matrix, another with groups, or another with scatter plants. It is helpful to think about one layer being superimposed on to another, even though in reality there may be no height differences between plants in one layer and those in another.

Generally, the first layer to be designed is the simplest, the one which deals with either a matrix or extensive blocks or groups; the second overlaying this deals with a finer texture of planting – smaller groups or more intricate patterning. Ecologists talk about ‘coarse-textured’ and ‘fine-textured’ plant communities: the former consists of large clumps, the latter a dense interweaving. Transferring this concept, one can talk about designing the coarse-textured first, and then overlaying that with the second, fine-textured layer.

Pink and white cultivars of Echinacea purpurea are scattered through a matrix of grasses on the High Line; the scatter plant principle of occasional flashes of pink and white among grass seedheads strongly evokes natural vegetation. The shrub is Cotinus coggygria, which is kept coppiced: cut down to base every few years to encourage bushy growth and more striking foliage.

Examples of the use of layers in planting. Tracing paper enables the planning of complex plantings to be broken down into several simpler processes.

An extract from plans for sections 28–29 of the High Line – this is just downtown of West 28th Street; the central horizontal gap in each one is the walkway. Layer One illustrates a simple and relatively open matrix where a transition is occurring between Panicum ‘Heiliger Hain’ (indicated by dots coming in from the left) and Calamagrostis brachytricha (shown by crosses, right) – these grasses are spaced at around 1 to 1.5 meters apart. Layer Two shows a range of perennials present as small clumps, often intermingled with the matrix grasses. About twenty different perennials (mostly late flowering) are included. To achieve the intermingling effect, the planting density of the perennials in the clumps is only 50 percent of normal to allow for the integration of grasses with them. Any space left is filled with grasses Sporobolus heterolepis and Bouteloua curtipendula, which are lower than the other two grasses. Keeping the density of the taller Calamagrostis and Panicum low helps to improve the visibility of the perennials. Much of the success of the High Line as a visual experience is the way that the flowering perennials poke out of the grasses.

An extract from plans for sections 35–39 of the High Line, between West 18th Street (to the left) and West 19th Street (to the right). In Layer One Panicum ‘Shenandoah’ and Molinia ‘Moorhexe’ are used as a matrix, and scattered among them are blocks of other grasses. In Layer Two a variety of perennials indicated by alphabetic abbreviations are scattered in loose clumps – each abbreviation represents one plant.

An extract from plans for sections 26–27 of the High Line, just downtown of West 27th Street. This plan illustrates the transition from an open area dominated by perennials and grasses on the right, to a shrubby zone underplanted with woodland species on the left. It shows that a two-layer plan can illustrate two very different kinds of vegetation.

In Layer One, circles on the left illustrate the expected spread of tree and shrub species, while on the right the shapes illustrate perennial clumps. In both cases these will be the main and immediate visual impact. In Layer Two, areas for planting ground-cover and woodland perennials are indicated on the left, while on the right there is a matrix of grass (Panicum ‘Heiliger Hain’). Any gaps are filled with another grass species. In this latter area, bulbs and spring-flowering perennials are also included as randomized plants.

Plans are usually done at a scale of 1:100, which works well for perennials, as it allows enough detail to be shown. Large areas involving planting mixtures where it is not crucial or desirable to show individual plants can be done at smaller scales.

This is an excerpt from a plan for an area of shade-tolerant planting from sections 26–27 on the High Line (page 116 bottom). What is shown is an overlay to the planting plan with each plant group or combination indicated.

Sample of woodland floor plants in bed 17 of the High Line

|

Code |

Square meters |

Plants per square meter |

Plants per group |

Bed 17 |

|

974.3 |

|

|

Rail ties (sleepers), i.e. not planted |

|

97.8 |

|

|

Pachysandra procumbens + Phlox stolonifera 80/20% |

pach 1 |

36 |

12 |

432 |

|

pach 2 |

6 |

12 |

72 |

|

pach 3 |

8.3 |

12 |

100 |

|

pach 4 |

5 |

12 |

60 |

|

pach 5 |

34.8 |

12 |

418 |

|

pach 6 |

0.5 |

12 |

6 |

Adiantum pedatum + Asarum canadense 60/40% |

ad 1 |

1.4 |

10 |

14 |

|

ad 2 |

8.5 |

10 |

85 |

|

ad 3 |

57 |

10 |

570 |

|

ad 4 |

8.2 |

10 |

82 |

|

ad 5 |

6 |

10 |

60 |

|

ad 6 |

41.5 |

10 |

415 |

Polystichum setiferum ‘Herrenhausen’ |

pol 1 |

6.7 |

9 |

60 |

|

pol 2 |

5 |

9 |

45 |

|

pol 3 |

5.5 |

9 |

50 |

|

pol 4 |

6.2 |

9 |

56 |

|

pol 5 |

6.6 |

9 |

59 |

|

pol 6 |

5.4 |

9 |

49 |

Setting plants out:

Now get planting!