Perennials amidst self-sowing grasses.

Plants have evolved a whole series of strategies for survival in nature – not just of individuals, but more fundamentally of their genes. These survival strategies influence how plants grow in gardens and other designed landscapes. Understanding them is key to appreciating, and making the most of, the long-term performance of our plants.

HOW PERENNIAL ARE PERENNIALS?

Applying language to nature is rarely easy. We humans like to deal in hard and fast categories, and yet nature rarely does. A key concept in understanding nature is the gradient whereby black at one end turns imperceptibly into white at the other through infinite shades of gray. Language led by human understanding has to make decisions about where one category ends and another begins, so inevitably much subtle detail is lost. However, there is a particular failure in our inability to recognize the diversity of plant lifespans in the simple three-part division of plants into annuals, biennials and perennials – a failure which seems to cross languages.

Many gardeners know from experience that some annuals live for more than a year and some perennials always die after three or four years. Research I have undertaken, partly through observation but also through surveying experienced gardeners (66 of whom filled in a detailed questionnaire), indicates that a wide measure of agreement exists about which perennials are really perennial and which might more correctly be termed short-lived.

That some perennials might not live up to their name indicates there is potentially a big problem out there for professionals who wish to use perennials in planting schemes. Writers of reference books and others who have promoted perennials have rarely addressed this problem – indeed, their failure to do so is actually quite shocking. The problem has been compounded by the nursery trade, which, it might be argued, has something of a vested interest in not being too clear about what is really long-lived and what is not. The nursery trade, in fact, tends to be dominated by wholesale producers of plants for the retail garden centers. A great many of their products are quick-impact but short-lifespan plants; professional users and gardeners interested in sustainability are more likely to be interested in genuinely long-lived plants, but much less varietal development goes into these. Or to be more precise, the larger scale nurseries catering for the retail trade do little. Specialist nurseries do more work at this end, with more limited resources – Piet himself being an example; he has selected out some 70 new cultivars over the years, nearly all of them being naturally long-lived plants, the list including Aster, Eupatorium, Monarda, Salvia and Veronicastrum.

In our last book (Planting Design, 2005), we looked at some basic perennial categories. More recent research and thinking enables us to throw more light on these, and develop some more nuanced categories. One problem is that an enormous variety of herbaceous plants is available, and they simply do not fall into neat categories. There is also a wider variety of shrubs than we like to think. Looking at the problem in evolutionary terms, we can suppose that plants have evolved herbaceous and woody, annual and perennial lifestyles several times over – so there should be no surprise that there is such disparity and no obvious tidy pattern of classification.

LONGEVITY AND SURVIVAL STRATEGIES

In trying to understand how plants survive and coexist in the wild, ecologists have developed a number of different models. One of the most successful is the CSR model, which stands for Competitor, Stress-tolerator, Ruderal. The first two are self-explanatory, while ‘ruderal’ describes the behavior of short-lived plants which have an opportunist and pioneering lifestyle, such as the weeds which can occupy bare soil in a matter of weeks. The CSR model was developed at the University of Sheffield by J. Philip Grime in the 1970s. It is a way of understanding plant survival strategies – how plants survive and reproduce themselves in the wild or in their colonization of human-made spaces. A lot of this model makes sense to gardeners, and when I first came across it in the mid-1990s I was very impressed by how it explained so much about plant behavior and garden practice. For example, bare soil is important for ruderal growth, which explains why the traditional practice of constantly hoeing bare soil between plants is counter-productive: this is simply making an ideal seedbed for ruderals! The CSR model has had considerable impact in Germany, where it is used to provide a basis for different regimes of planting management. There is, however, scope for misunderstanding and misinterpretation, and I do feel that too much can be made of it.

Here I will briefly outline the CSR model, primarily because its core ideas provide some useful concepts and labels for us as gardeners and designers and because some discussion of plant performance is now framed in these terms by colleagues. However, little further reference will be made to it.

Competitors do literally this – compete. They are plants of high resource environments (full sun, fertile and moist soils). They are able to make effective use of these resources, and grow fast and spread quickly through spreading roots and side-shoots. All this growth leads them to compete strongly with each other – to the extent that they will often end up eliminating each other. This is why exceptionally fertile, moist habitats can sometimes end up being dominated by only one species. Examples include lush wetland plants, grasses and perennials of fertile meadow and prairie habitats.

Stress-tolerators are survivors where the three vital inputs for plant growth are reduced: solar radiation (light and heat), water and nutrients. They grow slowly and do all they can to conserve resources. Examples include tussock grasses of poor soils and exposed habitats, subshrubs in dry or windy places, wildflowers on dry rocky soils, shade-tolerant perennials.

Ruderals ‘live fast, die young’. They are opportunists and pioneers, seeding in gaps between other plants or in new environments. They grow rapidly and put a lot of energy into flowers and seed. They are usually short-lived, with the species surviving through its genes being scattered in plentiful seed. Examples are weeds of arable farmland, annuals of seasonally exposed riverbanks, and many plants of waste ground or disturbed places. Many, including a great many of those in cultivation, are annuals from regions with clear wet/dry seasons, such as Mediterranean and semi-desert climates.

It is often very instructive to think about plants in these terms. However, these are tendencies and not categories. The majority of plants are not pure competitors or stress-tolerators or ruderals; they combine elements of all three. It is not possible to put plants neatly into one category or another. For those involved in practical planting design and management, it is more useful to think about key aspects of plant performance, which I will do here, making reference to the CSR model where relevant.

Blue Symphytum caucasicum, a species of comfrey, is a very strong competitor and in fertile, moist soils can spread aggressively – perhaps more than any other ornamental perennial – but its blue flowers can be appreciated for several months. Here, however, its growth has diminished over the years, because of the competition of the roots of the tree Acer griseum; the building foundations are also probably limiting the plant’s availability to access moisture and nutrients. The lesson is that strong competitors may be very dependent on high levels of resources and suffer when they are not available. The silver is Lamium maculatum ‘Pink Nancy’, a much more modest and more stress-tolerant spreader. Also present is Geranium sanguineum (foliage left foreground), another modest but steady and drought-tolerant spreader, and a seedling of an Origanum species (right foreground), which spreads only minimally but seeds enthusiastically in many gardens.

LONG-TERM PLANT PERFORMANCE INDICATORS

For the practical designer and gardener there are four key indicators of long-term performance. Plant species tend to combine these in different ways.

Inherent longevity: some plants live a long time, while others do not, deteriorating even in ideal conditions. Anyone who has grown hollyhocks (Alcea hybrids), the classic English cottage garden flower, knows how in their third year they just look awful – lacking vigor, with woody growth which seems to have no energy for new shoots. That’s all there is to it – they are genetically programed to grow rapidly, seed, and then lose vigor and die.

Ability to spread through vegetative growth, not through seeding. Those new to gardening soon become aware that some perennials spread whereas others stay put and do not increase much in size.

Persistence: this is about the ability of a plant to stay in one place, holding its ground. Those who think the definition of a plant is that it does not move around have not had the experience of growing something like monardas, which may be planted in one spot and the following year appear in several places further afield, but often with no growth in the original planting area.

Ability to seed: how effectively a species reproduces itself by seeding in garden conditions.

Now, I will look at these performance indicators in more detail, in particular their implications for planting designers and gardeners.

INHERENT LONGEVITY

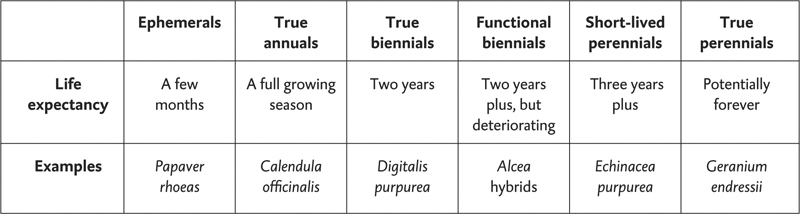

Annual, biennial and perennial are three key words we learn when we first take up gardening, but they are in fact arbitrary categories forced on what is actually a whole gradient of different genetically programmed plant lifespans. The table below illustrates the gradient of hereditary longevity among some common garden plants, with an indication of longevity on the middle row, and an example on the bottom. Needless to say, the categories are not clearly defined!

My main interest is in the right-hand side of the table. Frustratingly little research has been done on perennial longevity. Reports from gardeners tend to be consistent that some species do inevitably die after a number of years, but how long plants live can be highly variable. Many species appear to live for three to five years, and others go on for much longer but perhaps do not survive beyond ten. Environmental factors and competition often have a major impact on survival. A good example is the popular Echinacea purpurea, which is reported to live little beyond five years in the wild while the related E. pallida may survive for up to twenty. The ‘true perennials’ category contains plants which have a variety of growth habits; the most important distinction (discussed in ‘Ability to spread’ below) is between ‘clonal’ perennials (which spread) and ‘non-clonal’ (which do not).

How is it possible to tell whether or not a plant will be a true long-lived perennial? This is where the ‘rabbit’s eye view’ is important. Examine the base of the plant – if there are clearly shoots with their own independent root system, then the plant is clonal, so it is going to spread and be a long-term survivor. A good example is any one of the pink-flowered Geranium endressii or G. ×oxonianum cultivars. If, instead, all the roots and shoots appear to connect at one point, like a neck, and the shoots do not appear to have their own root systems, then the plant will be non-clonal: it has no ability to spread itself and could be short-lived. The lighter and more fibrous the root system, the more likely it is to be short-lived. Plants with a narrow point of connection between top and root growth but with a substantial and tuberous root system, however, are probably going to be long-lived. It appears that with some perennials the degree to which a plant is short-lived may vary across the species – it is an aspect of genetic variation.

Being short-lived indicates that the plant has a ruderal component to its survival strategy, so it is most likely a pioneer species, only able to survive by constantly seeking gaps or disturbance where existing vegetation is lacking. While most annuals in cultivation are species of seasonally dry habitats, where seedlings can grow in the rainy season and survive as seed when it is dry, short-lived perennials come from a variety of habitats. Many are woodland-edge plants, such as Aquilegia and Digitalis, possibly Echinacea as well – unstable habitats where change is constant as trees grow or are felled. Others are plants of grassland, where hillside soil slippage or ground disturbance caused by grazing animals is constantly making tiny gaps for seedlings to establish themselves, including Knautia or Leucanthemum vulgare. Some are wetland plants which take advantage of bare soil left exposed by flooding or seasonal water level changes (Lythrum salicaria or Verbena bonariensis). All these species are also vigorous growers, and so can be described as competitive-ruderal in CSR terms.

Longevity refers to the expected lifespan of a plant. It can sometimes be confused with speed of establishment; it is the experience of many gardeners that a young plant will often die, so it ends up being written off as short-lived. In fact, it may be a long-lived plant that is slow to establish. One paradox is that some very long-lived perennials spend most of their first years producing roots and making very few leaves; these roots will ensure long-term resilience and survival, but until they are in place, the weak top growth is vulnerable to slugs, drought or being overshadowed by a faster growing plant. They may be thought of as combining the competitive and stress-tolerant strategies. Dictamnus albus, originally a wildflower of dry habitats in central Europe, is a good example. Other examples are species of Baptisia – key prairie plants which can grow very slowly in their first years but can be immensely long-lived once established – and the prairie grass Sporobolus heterolepis.

Early morning sun on Persicaria amplexicualis ‘Roseum’ and a Molinia cultivar. In the foreground are the deep red button heads of Knautia macedonica, a plant which appears to be short-lived, but makes up for this by producing large quantities of seed: self-seeding is needed if it is to persist. Behind it are the heads of Verbena bonariensis, an annual of dry-season riverbanks in Argentina, but in cultivation a very short-lived perennial; it almost inevitably self-seeds in gardens, however. August at Pensthorpe in Norfolk.

Peucedanum verticillare has a habit very typical of umbellifers. It is monocarpic, which means that it dies after flowering, which occurs after two or three years’ growth. However, it self-seeds well in most gardens. Its 2.5 meter high seedheads make a magnificent winter spectacle.

Aquilegia vulgaris is a good example of a non-clonal perennial. This plant is several years old, but there are no shoots with their own independent root system, only one point of connection between the top growth and the roots.

A young Solidago rugosa shows a mass of shoots and roots, with several new shoots emerging on the right. Because each one of the older shoots has its own root system it can become an individual plant if the clump is damaged – so it is clonal.

Euphorbia cyparissias is a notorious spreader, with roots which emerge as shoots some 20 centimeters away from the parent plant. This habit can be useful for filling space, especially since taller plants are liable to suppress it. The emerging shoots are Baptisia alba.

A great many popular garden perennials do seem to come into the ‘short-lived’ category. So, what is the point of growing them? Annuals and biennials put a larger proportion of their energy into flowers to ensure seed for their continued survival – which makes them attractive plants to grow, especially since their flowering season is often longer than that of perennials. It is the same with short-lived perennials – they make a trade-off between flowers/seed and persistent, spreading growth. Many are free-flowering and showy, so of course we want to grow them. This may be fine for the private gardener or the heavily managed and well-resourced public space, but for anyone wanting to plan for the long term or with limited money or resources for propagation, such perennials should be only a small proportion of the planting.

Self-seeding is a major part of the garden at Montpelier Cottage, Herefordshire. Natural methods of increase of vigorous species are encouraged in an attempt to build up a vegetation dense enough to minimize weed infiltration. Here, in early summer, various color forms of Aquilegia vulgaris and Geranium sylvaticum (foreground) seed alongside steadily expanding clumps of Persicaria bistorta ‘Superba’ (right).

Late summer plantings in the Montpelier Cottage garden include self-seeding Verbena bonariensis – an annual/short-lived perennial (foreground) – and traditional cottage garden hollyhocks (Alcea rosea), which also seed successfully on a variety of soil types. The yellow is Rudbeckia laciniata, a strongly spreading tall and very competitive perennial only suitable for situations where its vigor will be a virtue.

Talk to gardeners with any experience, and they will report that certain perennials have an aggressive habit of spread. Euphorbia cyparissias is a good example, with some gardeners regretting ever having introduced it into their patch, whereas others find that its ability to spread is actually very useful. As usual, the tendency of plants to spread is not clear cut; ecologists recognize a gradient, with plants that never produce side-shoots or spread at one end, and species which within the space of a year send out many runners to start new plants at the other. A useful technical word here is ramet – a ramet is a shoot with roots which can become an individual plant.

There is a great deal of variation in the level and type of ramet production. Some perennials produce a few very long ramets (several tens of centimeters), such as Euphorbia griffithii, so that it takes many years before the plant forms a clump rather than a scattering of shoots. Others produce a great many which grow a few centimeters a year, such as Geranium endressii, resulting in steadily spreading clumps, whereas some grow even more slowly, such as Geranium psilostemon. The rate at which the clump breaks up, releasing ramets to lead independent lives, varies. In the case of Monarda fistulosa this can happen in a year, but it may never happen with Geranium psilostemon except in the case of damage, when a broken fragment can regenerate the plant. One of the most aggressively spreading perennials is Lysimachia punctata, a favorite of old cottage gardens in Britain – once planted, or indeed dumped by the side of the road, it never dies; its combination of a high production of ramets several centimeters long and a high level of persistence means that it can form a dense clump impervious to other plants.

Vegetative spread has been described by ecologists as being either phalanx – where a clump expands in all directions at once – or guerrilla, where odd shoots appear at some distance from the parent plant, and are only followed by clump formation if there is little competition. Relatively few garden plants are guerrilla spreaders, since the tendency to send out runners was seen as a problem by traditional gardeners. Today, we might see such selective spreading ability as potentially useful in occupying space left bare by other plants.

Perennials with an ability to spread are classic competitor-strategy plants, fighting to increase the amount of space they control, to spread themselves at the expense of others. In the garden they are reliable long-lived plants, with an ability to recover from damage and often to hold off weed infiltration. Some of the more strongly spreading ones are able to rapidly fill space – a useful characteristic. Many, however, see this tendency as innately worrying, as if they are behaving like ‘weeds’. However, some rapidly spreading species are not effective competitors, dying out when they face the competition of others. Euphorbia cyparissias (a classic guerrilla) is a case in point: in the wild it appears only as odd shoots among grasses and other wildflowers, while in the garden it seems to be out-competed by taller plants (it is only some 30 centimeters tall). Plants which form steadily spreading dense clumps, such as many species of Geranium, Aster and Solidago, are particularly immune to weed infiltration and can self-repair after damage, and so can be seen as the mainstays of long-term plantings. With time, they form such large clumps that they will dominate the border, at the expense of shorter lived but self-seeding plants and non-clonal perennials. This will be the time to intervene, splitting them up to make more room for other plants in order to create variety.

Pycnanthemum muticum is an example of a strongly spreading clonal perennial. Long new shoots can be seen on the left. The rest of the plant is a mass of shoots with their own root systems. Next year the new shoots will look much like the shoot/root mass on the right, and will be sending out their own new shoots.

Emerging among Deschampsia shoots in early summer are stems of Euphorbia griffithii, a species which spreads slowly in a guerrilla fashion – erratically. These odd clumps appearing among other plants can be very attractive. It is June flowering. Allium hollandicum at the rear will repeat flower in many gardens from year to year, and on lighter soils may even self-seed.

Rapid spreaders have traditionally been regarded as thugs in the garden. However, given what has just been said, this may or may not be a problem, depending on how competitive they are – the problem is that we do not have much data on this. Gardeners can observe, however, how plants have performed in gardens with older plantings and from their own experience. Weak rapid spreaders with low persistence have value for infilling between larger plants; strong ones which persist or out-compete neighbors have most value in low-maintenance environments where strong weed suppression and minimal intervention are most important. Guerrilla spreaders can create some attractive spontaneous effects in a similar manner to self-seeding plants if only a few stems pop up here and there. Most species which spread like this are not capable of penetrating established clumps, so combine well with others.

Some perennials are potentially long-lived but often fail to do so in garden conditions – and, one suspects, often in the wild too. These include some species of Monarda and Achillea, which have wandering shoots, and often only live for a year or two. If the new shoots do not find good conditions or run into an established clump of something else, they are liable to die out quickly, although they are not inherently short-lived. Such plants can be said to have a low level of persistence. They could be considered as competitive-ruderals, as they are constantly on the move seeking out new territory. How long these plants survive in the garden is highly variable; soil, climate and the exact nature of the clone all make a difference. Continental climates with clear-cut winters and summers seem to be more favorable to the survival of many Monarda and Achillea varieties than maritime climates with their unpredictable winters of alternating periods of cold and damp.

Other perennials increase at a slower rate, but seem to march out from a central base, dying out there and so leaving a hole in the middle of the clump. Iris sibirica is a good example; old clumps split away, but for a variety of reasons this does seem to be a competitive species, and this habit does not reduce its usefulness as a long-term resident of most places where it is planted.

Most garden clonal perennials have growth which is strongly persistent. Among the most persistent plants are those that form an underground or ground-level semi-woody base. Some can only be regarded as non-clonal, because there seems to be no ability to naturally produce new independent plants; herbaceous species of Sedum (S. spectabile, S. telephium) are a good example. Others are distinctly clonal, but only in the sense that it may take a very long time (over ten years) for parts to separate, such as Veronicastrum virginicum. The hard, woody basal material is reminiscent of the woody plate-like structure which forms at the base of many shrubs. Plants with this structure may live for decades, and it is even possible that some wild clumps are centuries old.

It can be difficult to work out whether a plant has this type of basal structure, as opposed to a thicket of interconnected ground-level stems. It can most easily be found in spring by gently scraping back soil or debris around the top of the plant. A trowel rammed point down into the center of the plant will also produce a distinct ‘thonk’ if it hits a woody base.

Many bunch or tussock grasses (correctly cespitose species), like Deschampsia cespitosa and Molinia caerulea, are also highly persistent. They have a particular trick in that they recycle nutrients, their old leaves forming a mulch around the plant that gradually decays to release nutrients to feed new growth. Plants of some wild cespitose grasses are thought to be hundreds of years old.

Perennials with reduced persistence may seem like a bad bet for gardeners, and indeed in modern terms they are. However, many played an important role in the traditional herbaceous border and continue to be valued, largely because of a number of showy species which were used to produce a wide and opulent range of garden hybrids. Of these, hybrids of a North American aster (Aster novi-belgii, the New York aster) and of a phlox (Phlox paniculata or fall phlox) were both very important; they have a moderately spreading but non-persistent habit. Technically they are competitive-ruderals, their ancestors living in nature in unstable but fertile habitats such as woodland edges, riverbanks, creeksides and other unstable coastal or wetland situations. In such conditions, persistence in one place is a disadvantage, so evolution has driven these plants to move ever onwards. As garden plants they need high fertility. The conventional wisdom is that they also need dividing and replanting every two to three years to maintain their vigor; in practice this depends on the cultivar. Species which spread only slowly but tend to seed to replace themselves are another popular group: for example, Delphinium and Aconitum, natives of very fertile but often rapidly changing mountain woodland habitats. Clumps in the garden can rapidly lose vigor, necessitating propation to keep them going.

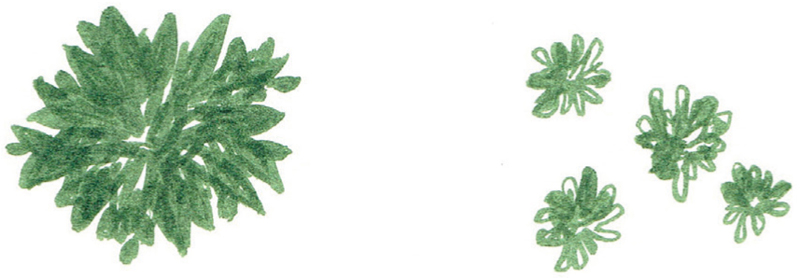

Strongly persistent perennials (left) form a solid clump and stay like this for many years. Less persistent perennials rapidly break up to form small clumps (right). There is a gradient of behaviour between the two.

Baptisia alba with Euphorbia cyparissias and grass Nassella tenuissima in late June. Baptisia, like several other North American prairie species, is slow to establish, as it builds up a large root system, but is very long-lived.

The value of slowly spreading and persistent plants to the gardener and designer is very clear. They can form a reliable part of long-term plantings, often without the problems of needing to control them after a few years, which can happen with those which are persistent but spread more strongly. However, whereas the latter can be easily dug up and divided, non-clonal or very slowly spreading persistent plants may not take very kindly to being divided, or division may be very difficult.

Less persistent perennials have a limited value in situations other than the highly managed private garden or public garden with good funding and dedicated staff. However, the genetic variation in some of these species appears to be wide, and may be one of the reasons why they were brought into cultivation in the first place. This genetic variation is not just about the range of flower color and flowering season, but also about habit, height, growth rate and vigor, so potentially there is a wide range of persistence too; as an example Phlox paniculata and related species such as the strong-growing P. amplifolia still offer a thick seam of diversity for nursery owners interested in making new selections on the basis of persistence and vigor as much as floral qualities.

Persistent perennials, produce long-lived growth which lasts for many years in the same position. Actaea ramosa ‘James Compton’ (left) spreads only very slowly, forming a dense mass of shoots and roots. Geranium sanguineum (right) is much faster growing and spreads relatively quickly, but as can be seen here from these sturdy, almost woody-looking roots, its growth is durable and persistent, so it forms clumps of solid growth, without dying back.

Pink Eupatorium maculatum ‘Riesenschirm’ alongside scarlet Monarda ‘Jacob Cline’ with pink Stachys officinalis ‘Hummelo’ in front. Eupatorium is long-lived and persistent, only slowly forming clumps, while Monarda can survive a long time but only if its highly mobile clumps are able to expand into new territory, so its persistence may be poor.

ABILITY TO SEED

When a species self-sows in the garden it can be thrilling – it is a sign that the plant is happy. Moderate self-sowing of shorter lived species can create the sense of a garden as being a healthy if artificial ecosystem. However, joy can be followed by annoyance if a plant seeds too aggressively and starts to compete with other species, or is in any other way problematic. Although long-lived and persistent perennials tend to have a lower rate of self-sowing precisely because they tend to be competitors, often with extensive or tough root systems, any that do more than very low-level self-sowing may create long-term problems.

Some garden plants are notorious seeders, scattering their offspring everywhere, sometimes to the point of becoming a weed. The level to which species self-seed is very unpredictable; whereas vegetative spread is more or less predictable, seeding is not – it is dependent on a great many factors, such as soil type, temperature and moisture levels in spring.

As a very general rule, the shorter the expected lifespan of a plant, the more seedlings it will produce. Biennials are very free with their seed, and the most troublesome if mass germination occurs: species of Verbascum are notorious for carpeting all available space with their seedlings, as is Eryngium giganteum, known as Miss Willmott’s ghost, after the English plantswoman of the early twentieth century who surreptitiously scattered seed in gardens she visited, so the plant would haunt her hosts for evermore. Some short-lived perennials such as Aquilegia vulgaris often produce large numbers of seedlings too, but rarely on anything like the same scale.

Biennials and short-lived perennials do not spread vegetatively, so at least the ability of individual plants to physically out-compete other members of a planting is limited. On the other hand, strongly competitive species with an ability to spread vegetatively often produce little seed. Many short-lived, generously seeding species have a narrow and upright habit, so their ability to physically spread over or compete with neighboring plants is relatively limited: large numbers of Aquilegia and Digitalis plants can grow alongside true perennials and not create problems. The same cannot be said for all, as anyone who has had to cope with the dense basal growth and sprawling flower stems of large numbers of Knautia macedonica or Verbena hastata will testify.

In planting design, it is questionable whether we can rely on the seeding abilities of self-sowing plants to regard them as permanent or even semi-permanent components of planting. In smaller gardens where maintenance tends to be more intensive, more perhaps might be allowed; in larger areas one can allow more seeding when the garden has established. Knowledge about levels of self-seeding has never been systematically gathered and is largely anecdotal. While short-lived self-seeding plants can be designed into plantings as minor components, the level at which they will continue to participate will depend very much on the skill, intuition and knowledge of those who manage them. Piet says, ‘I have a rule in planting design using biennials and vigorous self-seeders. I hardly use them and if I use it is as an extra in gardens that are established so that there is limited space and enough competition to limit their numbers.’

Allium carinatum spp. pulchellum alongside grass Nassella tenuissima in May. The grass is short-lived (three years is usual), but in most gardens it self-sows, sometimes extensively. The alliums have also sown themselves here through cracks in paving, a situation which often encourages self-seeding.

The sheer unpredictability of seeding makes it difficult to give too many recommendations for its use in management strategies. Most perennials will self-sow better on lighter soils, and some will produce prodigious levels of seedlings in mineral mulches like gravel, but in the final analysis the gardener has to observe, learn the behavior of their plants, and work with the level of seeding of the species. Moderate self-sowing of shorter lived plants is truly a boon, and of long-lived perennials too if they are not strongly spreading. Over-enthusiastic seeding can be a problem, and in extreme cases plants will need to be eliminated. With time, though, as a planting matures and long-lived components spread and monopolize space and resources, the bare-earth opportunities for short-lived ruderals will steadily diminish. Such species seize their advantages in the early years, but unless given active encouragement by the gardener they are bound to reduce as time and more robust, long-lived perennials march on.

Echinacea purpurea ‘Fatal Attraction’ growing among Calamintha nepeta subsp. nepetoides, the latter usefully filling out space between Echinacea clumps. In time Echinacea will die out, although in some situations it self-seeds. Its exceptionally attractive flowers are very popular, though, so its lack of longevity is widely seen as an acceptable price to pay.

Eupatorium maculatum ‘Snowball’ with Persicaria amplexicaulis in the background in August at Hummelo. Eupatorium only forms clumps slowly, while Persicaria does so at a somewhat faster rate. Like most long-lived perennials, both can seed in the garden but only modestly.

MAKING SENSE OF PERENNIALS – OR IS IT EASIER TO JUST GROW THEM?

Garden plants, and perennials in particular, are very hard to pigeonhole into categories, but since they behave in so many different ways over time, it is important that we have some way of making sense of their diversity. Realistically, it is best to think of a series of gradients; I have suggested some here related to performance: from short to long lived, from non-clonal perennials which do not spread vegetatively to those which spread aggressively, from those whose clumps are very persistent to those which constantly break up and, finally, the very wide variation in how likely a perennial is to self-seed under garden conditions.

There are relationships between these gradients, and a lot of research needs to be done to improve our understanding of them, and in particular how they relate to each other. It is also possible to set gradients against each other to form a grid.

Such mapping of plant performance characteristics can be very useful in planning for different kinds of planting, and there is definitely scope for research in this area to continue. However, plants are never consistent, which is perhaps part of their interest and attraction to us, so at the moment it is easier to abandon any idea of making categories, which will always be hedged about with ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’ and endless exceptions. Instead, think about a plant’s position on a series of gradients, which is what we have done in the Plant Directory at the end of the book. Fundamentally, though, the important thing is to enjoy what we grow, and accept the sometimes confused, tangled complexity of nature as part and parcel of our work and our passion.

|

Low persistence |

Medium persistence |

High persistence |

Low spreading ability |

Digitalis ferruginea |

Geranium sylvaticum |

Sedum telephium |

Medium spreading ability |

Phlox paniculata |

Iris sibirica |

Geranium endressii |

High spreading ability |

Monarda fistulosa |

Euphorbia cyparissias |

Lysimachia punctata |

Three of the grasses commonly used now in gardens and landscapes: Molinia ‘Transparent’ (top left), Panicum ‘Shenandoah’ (top right) and Sporobolus heterolepis in front. Their rate of spread varies: Panicum is the most likely to form clumps, whereas Molinia is a true cespitose species and will never go beyond a tight tussock. At the very front is Pycnanthemum muticum, a perennial which forms large colonies in its native USA, but in cooler summer climates is liable to be much less vigorous.