Chapter 11

Moving Between Identities: Embodied Code-Switching

By Marcia Warren Edelman

I am from Alvin and Louisita, Aurelio and Antonia Maria

I am from seekers pursuing: A better life. An education. A dream. An answer.

I am from coffee beans ground into fragrant powder, sweet nectar served in a tiny cup

and the slow rising heat of red chile stew on a winter’s day

I am from people swimming in so.much.talking.thatIcan’tgetawordinedgewise to

Full

Pregnant

Silences

I am from mountains and chamisas

all the time

and humid green, bursting flowers

sometimes

I am from narrow pathways between houses

and goat head stickers in callused feet

I am from a spark of recognition between opposite ends of the world

I am from Dave and Aurea and a slow dance in the kitchen

I am from Love

I am from stories and land and dreams and never-ending questions

“What are you?” What am I?

I am from the in-between spaces, the high ceiling of observation

shifting colors when the scenery is changed

I am from women leaving home

carrying their stories like clothes in a laundry basket

I am from men building families with the earth on their hands

and the heavens in their hearts

I am the next generation, and the last of my kind.

I am from brown earth in the skin, humid air in the blood, and blue sky in all dreams,

Standing.

I have lived between cultures physically and psychologically my entire life. My father is Native American, and through his side of the family I am proud to be an enrolled member of Santa Clara Pueblo, a tribe located in northern New Mexico. My mother immigrated to the United States from Brazil in the 1960s to teach university-level Portuguese and Spanish, and she herself was the granddaughter of Italian immigrants who came to Brazil in the late 1800s. On good days, I can speak my mother’s language of Portuguese, yet, like many of my generation, I was not taught our Native Tewa language because of historical and institutional oppression prohibiting the practice of speaking Native languages. I was born and raised in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which has its own rich cultural history quite different from that of the rest of the United States, and I married into a Jewish family with roots in Latin America.

I am grateful for the many cultures that are part of who I am and the life I have today, but it has not always been easy. As a child, comments such as “What are you?” “Where are you from?” “You’re so exotic!” felt like open and curious invitations to talk about myself, which I would eagerly accept. However, that enthusiasm would quickly fade as a cloud of question marks would appear on people’s faces once my answers became longer and more complicated than they anticipated. As time passed, I received the same questions but with the added assumptions and stereotypes that came along with the identities I named. I began to feel that uncomfortable difference between how others saw me and how I viewed myself . . . and somehow knew that I could not, and would never, truly satisfy the expectation of how my cultural identities were supposed to show up.

But something was happening to me even before the conversations started. Growing up, I was regularly immersed in each of my parent’s cultures without knowing the languages for either. Without a means to communicate, but with a strong desire to understand, I became very good at orienting outside myself, constantly scanning others to adjust myself to my social surroundings. Over time, my somatic sense of self—the core of my sensations, movements, observations—developed into highly responsive and pliable skills that could reflect whatever identity was needed in the appropriate context. I didn’t have words for what I was doing, but the distinct ways in which I literally moved in between my cultural identities were being formed.

This body experience did not have a name until I entered a graduate program in somatic counseling and was asked to write a paper on my own movement patterns.* As I began to examine my movement histories, I realized I did not have just one: I actually moved and held myself differently in Brazil than I did in Santa Clara Pueblo, and, more confusingly, I wasn’t sure what movement pattern, gesture, or posture would show up when I was outside both of those places. Soon after this assignment, I heard the term code-switching for the first time and realized there was a name to my experience. I began researching and eventually devised my own model that bridged the worlds of multicultural identity, code-switching, and somatic awareness.

My model, called Embodied Code-Switching, and the tools that work with it, are meant to support in two ways the multicultural person’s experience of moving between identities. First, it uses the body-based worlds of sensation and nonverbal communication to illuminate and strengthen the experience of having a multicultural identity and code-switching. Second, it seeks to provide a way to expand code-switching from an automatic reaction into a proactive, embodied skill that enables multicultural individuals to choose the ways they respond and adapt to different cultures. At its core, Embodied Code-Switching recognizes the body as a source of information and abilities and thus can change the quality of code-switching from a place of “managing” competing identities to one where a multicultural person can express cultural identities with more ease and fluidity.

Being Multicultural

The ultimate in inclusive terminology, multiculturalism has been used to describe the intersection of various forms of culture, which can include affiliations based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, sexual identity, ability, religion, geographic area, age, and any combination of these.1 This expanded view of culture can be seen in the increasing number of individuals who are choosing to identify with more than one racial or ethnic identity on the United States Census, making them part of one of the fastest growing populations in the United States today.* The ability to choose to mark more than one box on the form has the potential to dismantle the strict lines around self-identification, which presents both an opportunity and a challenge to people facing questions of how to self-identify in a world attached to categories and seeking to express their various cultural identities in ways that are personally and socially supported.

The irony can be that, although it seems that a larger community of multicultural people may be forming, the actual feeling of being multicultural can often be isolating and confusing. In their work on multicultural identity, Verónica Navarette Vivero and Sharon Rae Jenkins named this physical and psychological state as cultural homelessness: the feeling of holding a set of experiences, feelings, and thoughts that do not fit any existing constructs, which results in a sense of not belonging or being accepted because of one’s perpetual uniqueness.2 Vivero and Jenkins found that this sense of a separate identity lent itself to the development of certain skills, such as an increased sense of heightened awareness of cues in the environment to adjust language and behavior effectively as well as highly attuned sensitivity toward others’ expressions and feelings. And it also comes with feelings of rejection, isolation, and confusion—often overlaid with a strong sense “of ‘wanting to be home’ but not knowing what ‘home’ is or how it feels.”3

I was struck by how much this article spoke to my own experience of feeling “in between” spaces and places, not only in the world but also in myself. I wanted to find more voices that could describe this unique landscape and was led to Dr. Maria P. P. Root, a researcher and author who sees multicultural identity as a process—not an endpoint—with strategies to navigate the journey. Root describes the development of multicultural identity as a nonlinear process that includes the impact of inherited influences, traits, and socialization agents. She posits that context is essential to identity development and that one must find different ways to navigate the many cultural environments encountered over a lifetime. Root calls this kind of navigation “border crossings,” which include the following strategies:

- “having both feet in both groups” by holding, respecting, and merging multiple cultural perspectives simultaneously

- shifting the foreground and background of identity as one crosses between and among social contexts or environments

- “sitting on the border” by identifying oneself as multicultural and not having one’s identity subject to deconstruction by social and institutional sources

- creating a home in one “camp” by holding one cultural identity regardless of social contexts, with the right to change that identity over time4

Root also offers what she calls “A Bill of Rights for Racially Mixed People,”5 which offers a similar set of declarations to support multicultural people finding their own power in choice around self-identification and self-care.

The works of Root, as well as those of Vivero and Jenkins, highlight the importance of naming multicultural identity as its own experience—one that can hold great challenges but also great opportunities and skills.* The abilities to navigate many cultural environments, adjust to changing social norms, and shift one’s own internal thinking and behavior are all powerful skills in their own right. The key is to bring them forward with self-awareness and find one’s own sense of self amid the constant shifts.

Code-Switching

Many of us subtly, reflexively change the way we express ourselves all the time. We’re hop-scotching between different cultural and linguistic spaces and different parts of our own identities—sometimes within a single interaction.6

Today, code-switching has begun to enter popular culture as a term to describe the complex dance of reconciling one’s own inner awareness with the outside pressures associated with expressing racial, ethnic, and cultural identities. For example, discussions on code-switching have appeared in the United States through media such as National Public Radio’s (NPR’s) Code Switch blog and podcast as well as television (the work of comedians Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele often focus on code-switching) and online programming. As issues around diversity and difference become mainstream, recognizing the conversation around acknowledging and supporting the expression of individuals’ identities becomes more and more important.

So, what exactly is code-switching? The term itself first appeared in the field of linguistics to describe the phenomenon of bilingual individuals switching between languages. Later, it appeared in the field of psychology in studies of racial identity models and in studies that explored the ways social and environmental cues prompted the act of code-switching in the brain and through behavior.

In general, code-switching describes the dynamic way that multicultural individuals change their perceptions and behaviors to respond to different cultural situations, and its purpose seems to revolve around adaptation and survival. For example, in situations of racism, one way code-switching has been used is as a “self-altering coping strategy,”7 which often results in the denial of part or all of one’s identity. Others have described this kind of behavioral shifting as “chameleon-like,” where code-switchers slip into their identities, like they would clothes or a costume (depending on how authentic these identities feel), to adapt to different social contexts.8 Many consider code-switching a strength of multicultural individuals, a skill to ensure access to social and economic resources. But it can also be a constant challenge, drawing on enormous reserves of energy to manage the need to switch and bringing a sense of fragmentation and stress.*

Code-Switching in the Brain

For those of us who code-switch, we have a sense of when it happens and, perhaps, the ways the switch affects our thoughts and actions. But until recently, the actual act of code-switching had not been studied. In the year 2000, researchers pinpointed how code-switching occurred in real time by observing and measuring the brain as it made a “frame switch” between cultural mindsets on a completely symbolic level.9 Instead of looking at language use or behavior between people, researchers presented participants with icons and pictures, which aimed at observing how the brains of bicultural individuals shifted between their cultural identities and how they assigned cultural norms based on priming effects.

Participants consisted of two groups of Westernized students from Hong Kong. One group was shown a series of images of well-known cultural icons from the United States, such as the US Capitol building, and the other group was shown icons from China, such as the Great Wall of China. After being shown the icons, each group was shown a picture of one fish swimming apart from a group of fish. Each participant was asked to interpret the behavior of the single fish using a 12-point scale, in which the number 1 meant the fish was more internally motivated and the number 12 meant the fish was more affected by the group. The participants were then shown the icons again and asked to write their own description of the behavior of the fish without using the scale.

In both experiments, the participants who viewed the US cultural icons interpreted the behavior of the single fish as leading the group—a culturally appropriate assumption based on the more typical Western cultural value of individualism. Those who viewed the Chinese cultural icons interpreted the single fish as being chased or excluded from the group, again reflecting a collectivist (or group-oriented) norm typical of Eastern cultures.

Because all participants carried both cultures within themselves, this study provided one of the first examples of how bicultural brains have the capacity to correctly determine which identity needs to come forward to respond to visual cues—separate from language or the interaction of other individuals. In addition, it seemed that, when one specific identity was prompted, it came with its own set of culturally appropriate norms almost instantaneously and could make meanings of interpersonal behaviors through that lens. The switch was fast, responsive, and efficient—and happened completely on a nonverbal level.

Code-Switching through Embodied Culture

We’ve seen how code-switching can be observed in the brain and noticed in our thoughts and behaviors, but what happens in the body when we switch? A starting point to answer that question may lie within the idea of cultural embodiment. As Dr. Thomas Csordas observed, an individual’s “embodied experience is the starting point for analyzing human participation in a cultural world.”10 The fields of cultural anthropology and intercultural communication have looked at this topic for many years and have found that the ability to embody culture can be developed as a sensory experience on both physical and intuitive levels. Milton Bennett and Ida Castiglioni suggested that sensory stimuli, such as smells or sounds, contribute to developing a feel for a culture as well as having an internal sense of knowing what is culturally appropriate in certain moments (a handshake versus a bow, for example).11 It is this interactive relationship between sensation and awareness that they believed provides a basis for the embodiment of culture, a perspective shared by Csordas who described cultural embodiment as a means of gaining information about the world and the people within it through perception and attention facilitated by the body.

Csordas proposed that, through somatic awareness, individuals perceive and interact not only with their physical environment but also with their cultural environment. He called this type of awareness somatic modes of attention, which he viewed as “culturally elaborated ways of attending to and with one’s body in surroundings that include the embodied presence of others.”12 This idea is reflected in earlier discussions from Dr. Edward T. Hall regarding the consideration of time and uses of personal and interpersonal space, which can vary greatly between cultures.13

These concepts resonate greatly with my experience and my realization of the importance of the body in code-switching. For each time that I was immersed in Brazil or Santa Clara Pueblo as a child, I could feel my perceptions change, as well as my movements and the focus of my attention: I noticed different things, both externally and within myself. The taste of food and smells were the first sensations that told me I was in a different place. How loudly people spoke, how close they stood together, the firmness (or lightness) of hugs, and what kind of eye contact was held—all these subtle differences became signals to me to shift into another way of being.

I formed different identities for each location, with different postures and mannerisms, with the ultimate purpose to make sure I fit in with, or at least didn’t stand out from, the crowd. For me, code-switching ensured connection through relationships, through communication, through shared experience. It also meant I did not have a sense of self separate from the groups I was reflecting. Much like the study on frame-switching discussed earlier, I was the lone fish whose relation to the group completely depended upon who was looking at me and through what cultural lens I was being viewed—that is, until I began to integrate somatic awareness into the process and I found a new nonverbal language for my own kind of code-switching.

Embodied Code-Switching

“. . . one must learn to decipher movement meaning, just as one learns to speak a language . . . a movement may have different meanings in varied situations, while a given intent may be embodied in differing ways from culture to culture.”14

It is only recently in a Western cultural viewpoint that the body has been included as an intrinsic part of the human experience. Historical views of the body have often relegated it to the status of “other”: an entity to be conquered, denied, or ignored in the effort to achieve intellectual achievement or spiritual transcendence.15 In other viewpoints, the body was considered a symbol and metaphor for how we perceive the world and the supernatural, by nature a cultural artifact of its own.16

As a somatic counselor/body psychotherapist, I view the body as a source of information about a person’s state of being, a place where memories and emotions are held, as well as how histories are passed down to us from our ancestors. Noticing the breath, patterns of tension and relaxation, impulses to move—these all are part of the body’s way to communicate and express itself as a cultural being. As Hall described:

. . . people from different cultures not only speak different languages but, what is possibly more important, inhabit different sensory worlds. Selective screening of sensory data admits some things while filtering out others, so that experience as it is perceived through one set of culturally patterned sensory screens is quite different from experience perceived through another.17

By discovering our own ways of embodying culture through somatic awareness, we can develop a deeper knowledge and familiarity of the qualities of our identities and develop ways to prepare for code-switching when it occurs.

As discussed in this chapter, code-switching has its roots in the ongoing effort of multicultural individuals to adapt to various cultures, both within themselves and their environment. This type of constant movement between identities in response to social and cultural messages has an impact on all levels of a multicultural person’s experience—what is sensed, what is thought, and what is done. By using the Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop and the Identity Expression Infinity Loop (both described next), the adaptive skill of code-switching can be slowed down and observed, and choices can be made around behavior, nervous system regulation, and interactions with one’s environment.

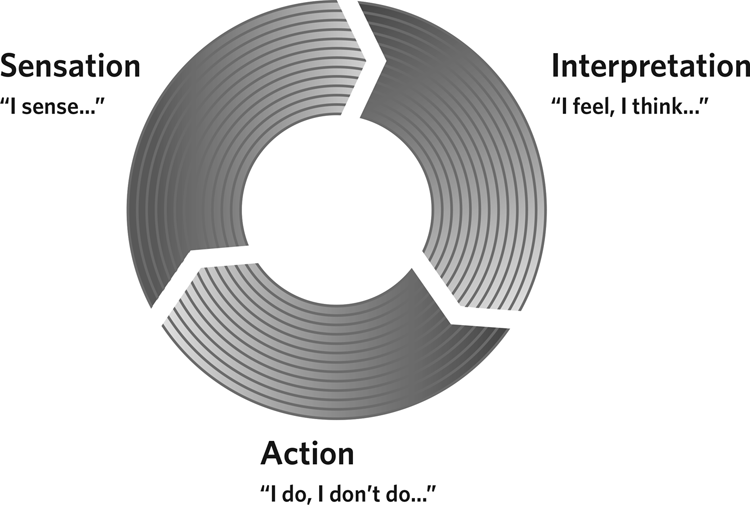

Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop

The Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop includes three entry points: Sensation, Interpretation, and Action. It has been designed to have more than one primary point of entry because the act of switching between cultural environments can present itself differently for each person. You may find that you have a good grounding in the experience of multicultural identity and need more attention on the somatic aspects of code-switching, or that you may be more familiar with your somatic states but have never applied a cultural lens to them. The following are descriptions of each point of entry in the Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop and suggestions on how to build awareness around them to recognize the qualities and impact of each area on the way you may experience code-switching.

The entry point of Sensation relates to the internalized state of the multicultural individual; the information received from this area comes from within the body through inner awareness of sensation (e.g., tightness, relaxation, increased heartbeat, breathing), as well as through the environment and interpersonal relationships (e.g., sights, sounds, movements, space, speed, physical proximity). This entry point may be the first place where individuals feel code-switching happen, both through what they notice outside of themselves and the impact it may have on how their bodies feel.

Figure 11-1: Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop

Activities for this point on the Loop focus on increasing sensory awareness through the lens of culture and identity. You can use this entry point to become aware of sensation in many ways; however, it is important to understand, and to hold within yourself or others, that somatic awareness is not just a process of noticing sensations in the body. Our bodies are influenced by cultural and societal norms, expectations, and intergenerational trauma, and carry silent messages of power, oppression, and privilege. Asking yourself to feel into sensation requires your gentle attention and respect for the presence of these embodied legacies, and a larger awareness of the balance between safety and risk as you begin to explore your body’s own language.

Personal Exercise 1: Awakening the Senses

One way you can begin identifying how you interact with your senses is by taking an “inventory of sensing,” which is an assignment that Hall, cultural anthropologist and father of the field of intercultural communication, would often give in his classes on culture and communication. Hall created a sensory “buffet” of categories and questions aimed to help his students explore their preferences for each of the five primary physical senses (hearing, sight, smell, taste, touch) as well as other sensations related to temperature, physical movement, and interpersonal space and boundaries. You can do this at home by listing all the senses mentioned and rating them from 1 (low sensitivity) to 5 (high sensitivity). Based on your answers, you can explore how these sensitivities or preferences affect the ways you sense the world and recall experience, and how your own cultural upbringing and contexts influence what senses you use.

You can also get to know your personal sensory state through a body scan, which does not require a special place and time. At any moment in your day, take a pause and bring your attention inward. Sweep your focus over your body, starting anywhere you like. As you scan, notice any internal sensations you might be feeling: check in with your breathing (Is it Shallow? Deep? Slow or quick?), find areas of tension and relaxation, try on qualities of personal space and movement (Am I moving quickly? Do I move differently with people around than at home? How close do I like others to be?). As you notice the current state of your body, offer questions to yourself about any emotions that come along with those sensations as well as any messages that have judgments or beliefs and, perhaps, how these might reflect cultural norms that have been passed down to you nonverbally. Once those connections have been made or recognized, scan yourself again and see if anything has shifted.

The Interpretation entry point represents the place where beliefs, thoughts, and emotions enter the process of code-switching and where meanings are made and internalized. This entry point offers you a space to share personal stories, family histories, and inner reflections on the ways your cultures have affected your sense of self, relationships, and worldviews. It is often here where questions of identity come with certain qualities—comfort or conflict, being “enough” or “not enough,” ability versus lack of knowledge. It can be a place of confusing messages and unclear direction as well as an opportunity to hold a variety of messages on beliefs and self-judgments with gentle awareness and equanimity.

Personal Exercise 2: Storytelling through the Body

An important part of Embodied Code-Switching is finding our stories in our bodies and being able to express them. This exercise is best done with another person with whom you feel comfortable sharing. Begin by choosing a personal story or memory about, for example, your cultural heritage, immigration history, or identity experience, and ask your partner to receive you in whatever way you want to express your story (e.g., signing, speaking, moving). As you share, notice how your body begins to participate—your gestures might change, another language may emerge, or you might find yourself feeling smaller or more expansive. Ask yourself how your story moves you in the ways you think, feel, and see the world and others. When your story feels complete, offer your partner the chance to reflect on what was noticed in you as you shared your story and how your partner received it in his or her own body. You can then switch places and become the receiver as your partner shares a story. After both of you have finished, you may want to take the opportunity to explore what came up for each of you that was culturally related (e.g., questions, feelings of discomfort or familiarity, mutual understanding) and the ways in which you each experienced these states in your body as you told your stories.

Lastly, the entry point of Action reflects not only what happens as you enter different cultural environments where specific identities are called to arise, but also what choices can become available once information from the Sensation and Interpretation points are included in the experience. The main area to explore here is noticing your own behavior in relation to other individuals and to groups, with a focus on how your nonverbal communication (body movements, use of interpersonal space, expressions, gestures) may change in each cultural setting. Through journaling, or perhaps in conversation with a partner, you can find a memory in which you notice what behaviors and nonverbal communication patterns came forward, or became minimized or suppressed, in each cultural environment and then how they may have changed when you entered another environment. Based on these observations, you can explore how this act of adjusting yourself might affect how your cultural identities can be expressed and what choices you would make to help their expression feel more comfortable and fluid.

Personal Exercise 3: The Power of Our Nonverbals (or “what we do when we’re not talking”)

This exercise provides a direct and often surprising way for people to feel how different types of personal space can quickly produce reactions in the body and feed into thoughts and beliefs. To begin, find a partner and determine who begins first as the mover and who will stand still (you will switch places later so each has the experience). The mover is asked to face and begin walking toward the partner, while the person standing still is asked to do two things—first, to let the mover know when a personal space boundary has been reached and, second, to notice what internal sensations and/or external cues signaled that the boundary had been reached. The person standing still then can share with the mover what was noticed about the boundary, the sensations that came up, and, most importantly, any emotions the person standing still felt or actions the person standing still wanted to take once personal space was entered. The partners then switch roles and repeat the exercise.

The goal of the exercise is to link the body’s physiological responses (e.g., tension in the muscles, holding the breath) with spatial preferences (small or large personal “bubbles”) as they are found through sensation and then place a cultural lens on top. When culture and identity are added to this exercise, people gain a different insight into how these interactions could increase misunderstanding, negative impressions, and even heightened physical responses between people of different races, cultures, or gender.

This type of interaction can include role play or a discussion that examines an encounter between two people of different cultures when a boundary is crossed and each person feels a physiological response. For example, Person A crosses into Person B’s boundary, and Person B (without speaking) moves away or averts the eyes. Both people notice how they interpret the nonverbal signals they received from the other (“that person got too close to me, how rude that they don’t respect my space” or “that person won’t look me in the eye, they’re not trustworthy”) and then explore the ways in which that initial encounter could potentially become generalized into stereotypes (“all of those people are rude” or “I can’t trust those people”).

By slowing down the reaction process, we can take the opportunity to examine how nonverbal messages have the potential to influence behavior and beliefs, which then affect relationships and social systems on a larger scale—and, if not corrected or changed, result in repeated patterns of cultural discord that can take generations to correct.

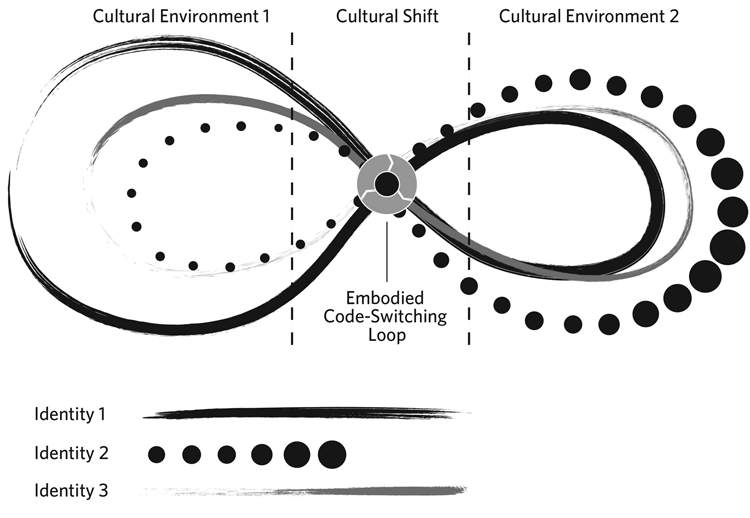

Identity Expression Infinity Loop

The Identity Expression Infinity Loop places the process of Embodied Code-Switching into a larger context to show the movement of multicultural people’s identities as they shift between social and cultural environments. Figure 11-2 represents this three-dimensional process as a two-dimensional picture by showing three identities (represented by different patterns and shades) as a person switches between two cultural environments. For the purposes of this example, I will use my own cultural background to illustrate: On one side of the Loop, Identity 1, which I will call my multicultural identity, is more present as it responds to Cultural Environment 1, which can be represented as the town I live in currently. On the other side, my Santa Clara Pueblo identity (Identity 2) comes forward when I go to the Pueblo (Cultural Environment 2). Identity 3, which I will designate my Brazilian identity, remains present but is not active because it has not been prompted by either of the environments represented in the Loop—although sometimes it does like to pop out unexpectedly as a strong desire to hug people and speak loudly! It is important to note that all three of my racial, ethnic, and cultural identities coexist in this model, responding in their own unique ways to whatever environment I find myself in and that this constant inner dance can be unpredictable, surprising, and completely natural.

Figure 11-2: Identity Expression Infinity Loop

In the center of the Identity Expression Infinity Loop is the space that represents the cultural shift between environments, and in the middle of that space is the moment in time when the Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop becomes active. Going back to my personal example, the moment I turn off the highway and enter Santa Clara Pueblo, I can feel new information coming into my Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop, via the Sensation, Interpretation, and Action entry points, and giving me signals that affect the way I hold myself and alter my sense of time, conversation style, or other responses. The experience acts much like a gear, switching me from one identity to another to let me adapt to my surroundings and be in relationship with my relatives and Pueblo community.

To be sure, code-switching often happens so quickly that we often do not have the opportunity to pause and prepare. For this reason, it is important to give yourself the chance to step back from the experience and slow down your own code-switching process to notice what happened internally, identify what external cues prompted the switch, and become curious about what was being gained or lost in the switch. Based on the information you discover, you can then develop choices and resources that will help you regulate the expression of the identity being called forward next time.

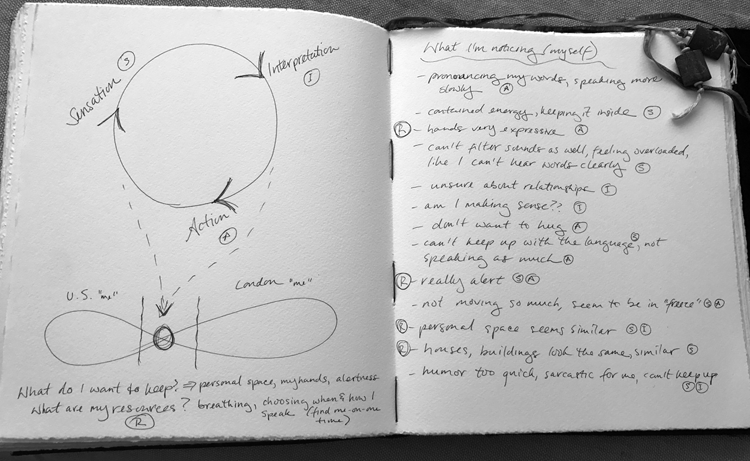

Putting It All Together: Marcia Goes to London

A few years ago, my family and I traveled to London to visit English friends we had known for more than a decade. We had met them during their time living in the United States and had shared milestones together, such as weddings and the birth of our children, so I felt I knew them very well. When they moved back to London, we decided to visit them in their home land, and I thought I was prepared for whatever cultural differences would arise—after all, I knew my friends and the language would not be that different, right? Wrong. After about two days, I started noticing that everything felt “off,” and I couldn’t quite pinpoint the reasons. I decided to turn to my journal and try out my own model to see if I could decipher what was happening to me.

I began by sketching out my Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop with the three entry points on one page, and, on another, I wrote down what I was noticing about my own sensations, observations, and thoughts. I didn’t categorize anything right away; it was important to just let the words appear without judgment or explanation. When the list felt complete, I began to categorize each observation with its place or places on the Loop. Once they were separated out, I could start making connections between what I was sensing, what I was thinking, and then what I was doing (or not doing).

The next step was to sketch out the Identity Expression Infinity Loop and show the two cultural environments and identities that I felt were present in that moment. Given that this was an international experience, I recognized that my US “self” was the predominant identity that was encountering a different culture in London. I went back to my list and started to consider which observations could be resources for the rest of the time I was in London, supporting me to feel comfortable within myself and better able to connect with my friends. I placed the letter R next to those and came up with some strategies: I would keep my personal expression of using my hands, I would give myself permission to speak at the pace and in the contexts that felt easier for me, and I would remember to breathe when I felt tense.

Figure 11-3: Personal Example of Code-Switching Feedback Loop and Identity Expression Infinity Loop

Once I could see everything in front of me, the overall sense of unease I had initially felt dissipated. I felt more open to noticing the differences of English culture and seeing my friends fully in their own English identities, and I was able to enjoy the rest of my time there.

Conclusion

“. . . everything that has ever happened to us . . . is inscribed upon our body, creating a living archaeological record.”18

What does it mean to be multicultural? For some, it describes two or more cultural identities inherited from birth or created by life events. For others, it can be a lived experience as global nomads or Third Culture Kids. A common feeling is that our sense of self is not tied to one group or one language—our identities move in between spaces and places. As a result, many multicultural people find themselves constantly aware of the interplay of self, other, and environment.

Code-switching is a skill that facilitates these transitions as our identities shift internally, as well as when we shift between physical cultural environments. Most times, we can see the switch happening through a change in language or behavior. But what about the internal experience of code-switching: the nonverbal signals we receive, the way our movements change, our sense of personal space, and even the thoughts and emotions that go along with code-switching? What do our bodies know before our minds (and our actions) make that transition from one culture to another?

This chapter has attempted to bridge a connection between the conversations on multicultural identity and what it means to embody culture through one aspect of multicultural identity expression: Embodied Code-Switching. Using tools such as the Embodied Code-Switching Feedback Loop and the Identity Expression Infinity Loop, together with discussions on multicultural identity, somatic awareness, and cultural embodiment, I explored new ideas around developing one’s own signals and sensations of code-switching and how to support resiliency in our various identities.

Why is this work important, and why now? We are living in a time when identity is not only personal, but it is also political. Reactions happen more quickly than thoughtful observation, and emotions seem to escalate faster than we have the time to respond. For those of us (all of us) who claim to support equity, inclusion, and the celebration of difference, we must begin the work within ourselves first. For, if we cannot love and accept our own diversity, how can we do the same for others? My hope is that this work offers multicultural people the potential to take what has felt like a challenge in their lives and build it into a powerful skill that values all parts of their experience. I believe that, to truly understand the cultures and identities we have inherited and created, our bodies must be removed from the sidelines and welcomed as active participants in the ways we define ourselves. In this way, we can begin to build a cultural “home” through our own sense of self and live authentically and compassionately with the cultures and relationships that are meaningful to us all.

Endnotes

Bibliography

Benet-Martínez, Verónica, Janxin Leu, Fiona Lee, and Michael W. Morris. “Negotiating Biculturalism Cultural Frame Switching in Biculturals with Oppositional versus Compatible Cultural Identities.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 33, no. 5 (2002): 492–516. doi:10.1177/0022022102033005005

Bennett, Milton J. and Ida Castiglioni. “Embodied Ethnocentrism and the Feeling of Culture: A Key to Training for Intercultural Competence.” In Handbook of Intercultural Training, 3rd ed., edited by Dan Landis, Janet M. Bennett, and Milton J. Bennett, 249–65. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2004.

Binning, Kevin R., Miguel M. Unzueta, Yuen J. Huo, and Ludwin E. Molina. “The Interpretation of Multiracial Status and Its Relation to Social Engagement and Psychological Well-Being.” Journal of Social Issues 65, no. 1 (2009): 35–49.

Caldwell, Christine. “The Somatic Umbrella.” In Getting in Touch: The Guide to New Body-Centered Therapies, edited by Christine Caldwell, 7–28. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books, 1997.

Csordas, Thomas J. “Somatic Modes of Attention.” Cultural Anthropology 8, no. 2 (1993): 135–56. doi:10.1525/can.1993.8.2.02a00010

Demby, Gene. “How Code-Switching Explains the World.” NPR Code Switch. Published April 8, 2013. www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2013/04/08/176064688/how-code-switching-explains-the-world.

Downie, Michelle, Richard Koestner, Shaha ElGeledi, and Kateri Cree. “The Impact of Cultural Internalization and Integration on Well-Being among Tricultural Individuals.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30, no. 3 (2004): 305–14. doi:10.1177/0146167203261298

Farhi, Donna. Bringing Yoga to Life: The Everyday Practice of Enlightened Living. HarperSanFrancisco, 2004.

Gardner, Wendy L., Shira Gabriel, and Kristy K. Dean. “The Individual as ‘Melting Pot’”: The Flexibility of Bicultural Self-Construants.” Current Psychology of Cognition 22, no. 2 (2004): 181–201.

Hall, Edward T. The Silent Language. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1959.

———. The Hidden Dimension. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1969.

———. Beyond Culture. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1976.

Hong, Ying-yi, Michael W. Morris, Chi-yue Chiu, and Verónica Benet-Martínez. “Multicultural Minds: A Dynamic Constructivist Approach to Culture and Cognition.” American Psychologist 55, no. 7 (2000): 709–20. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.55.7.709

Jones, Nicholas A. and Jungmiwha Bullock. The Two or More Races Population: 2010. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau, 2012.

LaFramboise, Teresa D., Hardin L. K. Coleman, and Jennifer Gerton. “Psychological Impact of Biculturalism: Evidence and Theory.” Psychological Bulletin 114, no. 3 (1993): 395–412.

Miville, Marie L., Madonna G. Constantine, Matthew F. Baysden, and Gloria So-Lloyd. “Chameleon Changes: An Exploration of Racial Identity Themes of Multiracial People.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 52, no. 4 (2005): 507–16. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.507

Moore, Carol-Lynne, and Kaoru Yamamoto. Beyond Words: Movement Observation and Analysis. Milton Park, Abington, Oxon: Routledge, 2012.

Nguyen, Angela-MinhTu D., and Verónica Benet-Martínez. “Multicultural Identity: What It Is and Why It Matters.” In The Psychology of Social and Cultural Diversity, edited by Richard J. Crisp, 87–114. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2010.

Pederson, Paul B. “Multiculturalism as a Generic Approach to Counseling.” Journal of Counseling & Development 70, no. 1 (1991): 1–7.

Rockquemore, Kerry Ann, David L. Brunsma, and Daniel J. Delgado. “Racing to Theory or Retheorizing Race? Understanding the Struggle to Build a Multiracial Identity Theory.” Journal of Social Issues 65, no. 1 (2009): 13–34. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01585.x

Root, Maria P. P. “Bill of Rights for People of Mixed Heritage.” 1993, 1994. www.drmariaroot.com/doc/BillOfRights.pdf.

———. “The Multiracial Experience: Racial Borders as a Significant Frontier in Racial Relations.” In The Multiracial Experience: Racial Borders as the New Frontier, edited by Maria P. P. Root, xiii–xxviii. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1996.

Sanchez, Diana T., Margaret Shih, and Julie A. Garcia. “Juggling Multiple Racial Identities: Malleable Racial Identification and Psychological Well-Being.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 15, no. 3 (2009): 243–54. doi:10.1037/a0014373

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Margaret M. Lock. “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1987): 6–41.

Shih, Margaret, Diana T. Sanchez, and Geoffrey C. Ho. “Costs and Benefits of Switching among Multiple Social Identities.” In The Psychology of Social and Cultural Diversity, edited by Richard J. Crisp, 62–83. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2010.

Sue, Derald Wing, Patricia Arredondo, and Roderick J. McDavis. “Multicultural Counseling Competencies and Standards: A Call to the Profession.” Journal of Counseling & Development 70 (1992): 477–86. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01642.x

Suzuki-Crumly, Julie, and Lauri L. Hyers. “The Relationship among Ethnic Identity, Psychological Well-Being, and Intergroup Competence: An Investigation of Two Biracial Groups.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 10, no. 2 (2004): 137–50. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.10.2.137

Terhune, Carol Parker. “Biculturalism, Code-Switching, and Shifting: The Experiences of Black Women in a Predominately White Environment.” International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities and Nations 5, no. 6 (2005/2006: 9–16.

Townsend, Sarah S. M., Hazel R. Markus, and Hilary B. Bergsieker. “My Choice, Your Categories: The Denial of Multiracial Identities.” Journal of Social Issues 65, no. 1 (2009): 185–204. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01594.x

Vivero, Verónica Navarrete, and Sharon Rae Jenkins. “Existential Hazards of the Multicultural Individual: Defining and Understanding ‘Cultural Homelessness.’” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 5, no. 1 (1999): 6–26. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.5.1.6