Chapter 13

Transforming Distress: Grieving Dysphoric Bodies in Community

By Beit Gorski

A Model of Body Psychotherapeutic Group Intervention to Support Management of Body Dysphoria as Experienced by Preoperative Transsexuals

Dear reader, I’m imagining you reading this, and I believe you’re reaching for hope. I believe you have an earnest desire to uplift trans communities and provide something resembling a safe haven from the daily distress of living in an actively transphobic society. Many of you are yourselves transgender (having a gender identity different from how you were assigned at birth) and have seen the need for culturally competent therapeutic support on the front lines. Many of you are cisgender (your gender identity is not different from how you were assigned at birth) are seeking ways to become a reliable and knowledgeable support for trans folks, and are hoping for practical ways to act in solidarity. Regardless of your gender history (cis or trans), you may not have experienced body dysphoria (distress from having a gendered body that is incongruent with your gender identity). You might try to imagine what it could be like to wake up tomorrow morning with a differently gendered body. However, to try on the experience of being transsexual (someone who experiences body dysphoria), you might instead imagine waking up tomorrow morning with the same body and identity you’ve always had . . . only now everyone else seems to be convinced that you are otherwise. Most will misgender you as a matter of habit, and many will even disagree with you about your own identity. They may even go so far as to use your body as evidence that you are incorrect about your gender. Next, imagine that this experience has been happening to you since your earliest developmental years and has shaped your relationship to your gendered body.

Not all transgender people are transsexual, but most experience social dysphoria (the distress caused by being misgendered as one moves through the world), which I believe is an important contributing factor to the development of body dysphoria. The following group intervention, Transforming Distress (TD), is designed specifically to support those who experience body dysphoria and are unable to access the medically necessary interventions proven to be effective (hormone treatment and/or surgical procedures that bring the body into perceived congruence). I invite you to join me in an exploration of body dysphoria management (not cure) through somatic awareness and community connection.

Why So Urgent?

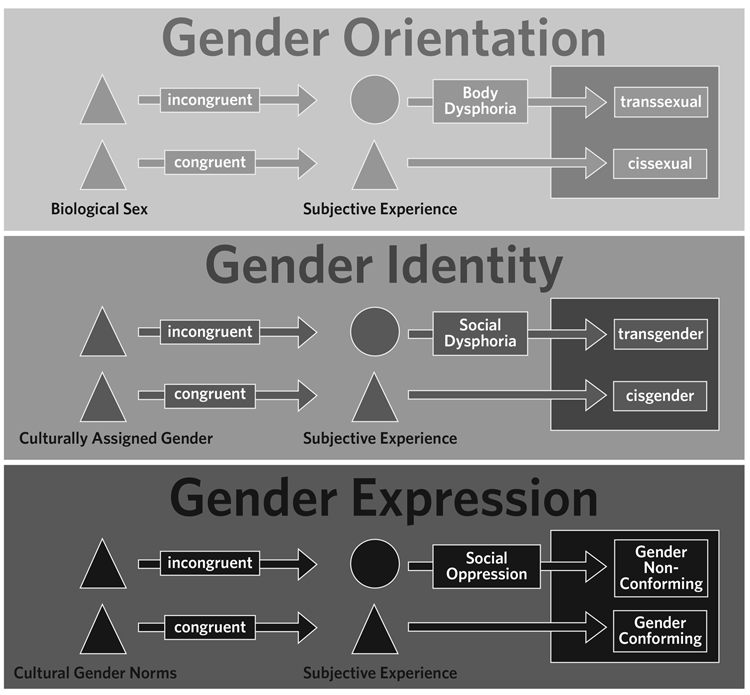

Missing from the current clinical literature is a standardized definition of body dysphoria as distinguished from social dysphoria, both of which are different from behavior and attitude responses to gender-themed systemic oppression (see Figure 13-1).

Using TD requires a clear separation of these two terms, though they are related experiences and many experience them concurrently. As I mentioned, not all trans folks experience body dysphoria—indeed, some choose hormone and/or surgical interventions simply as an act of self-love and affirmation while others choose no interventions at all. But for those living with body dysphoria, life can become unbearable. Pain, anger, grief, and sadness can stack up before we’ve even gotten dressed in the morning: pain that screams, “There’s something wrong here, something needs to change!”; anger that our bodies have been used to invalidate the self-evident truth of our gender(s); grief for the bodies we weren’t given, the social milestones we missed; and the sadness of feeling so disconnected from the bodies we do have. Body dysphoria can fuel the skyrocketing suicide rates in the trans communities (about 40 percent) and can lead to social isolation, severe anxiety, and even agoraphobia (fear of going out in public, and/or fear of having a panic attack in an unsafe location).

Figure 13-1: Differences among Body Dysphoria, Social Dysphoria, and Oppressive Social Norms

When I, as a transsexual with a significant trauma history, first began to meditate, I found that sitting with my body was like holding a hurricane inside of me. All that trauma swirled furiously around within me with sharp bits of psychic shrapnel and internalized transphobia. I couldn’t understand how to stay with embodiment—and survive. As a child, I very rarely felt embodied, and the experience always caused me great pain. I used to think of it as the “great crunch of reality” and avoided it whenever possible. Having body dysphoria often means completely marginalizing the body in a state of suspended grief by clamping down on the body, bracing against the pain, suppressing the anger, and, frequently, binding the body as though casting a spell of disembodiment in the interest of survival and daily functioning. TD offers a starting block to invite participants to sit next to their pain, to safely discharge their anger, and to validate all of these experiences in the context of community and building networks of chosen family systems. When practicing TD in a closed supportive group setting across the six-week curriculum (one week per module), participants learn to sit next to their experiences of body dysphoria as an anam cara (soul friend), offering the opportunity to discover their own embodied empowerment, expand into communities with confidence and self-care, and effect meaningful change.

This model for managing body dysphoria and the opportunity for transsexual patients to be culturally informed about support in recovering from the trauma of lifelong body dysphoria are long overdue and urgently needed. As trans visibility increases, legal rights and considerations are slowly catching up with community acceptance, and clinicians must understand the impact of cultural competence when treating vulnerable clients. To casual observers, Kyler Prescott appeared to have an embodied life of social privilege and comfort. The white fourteen-year-old boy lived comfortably with his family in an affluent neighborhood of San Diego and thrived as an accomplished pianist who enjoyed sketching, creative writing, and tending to his many beloved pets. However, Kyler was assigned female at birth and experienced body dysphoria. This painful condition grew more severe as he entered puberty and was exacerbated by the social dysphoria from being “bullied and harassed about his gender identity by his peers and teachers.”1 His poetry describes the heartache and longing that he experienced when searching his mirror for the boy he knew himself to be:

I’ve been looking for him for years, but I seem to grow farther away from him with each passing day, He’s trapped inside this body, wrapped in society’s chains that keep him from escaping.2

Kyler began to self-harm to cope with his dysphoria and struggled with impulses to kill himself. Six weeks after he was discharged from an adolescent psychiatric unit where nurses and staff consistently misgendered and invalidated him, Kyler died from suicide.

As I write this, in 2017, political movements are working to overturn the recent gains for trans rights, including removal of the protections for health care granted by the Affordable Care Act. At this same time, a record number of transsexual millennials are daring to come out as trans and seek the medically necessary interventions (hormone treatment and/or surgical interventions) that are nothing short of life-saving in the context of body dysphoria. Mental health professionals are slowly becoming aware of the urgent need for culturally competent treatments to manage dysphoria, especially because the medically necessary interventions for gender dysphoria (the DSM umbrella category that includes both body and social dysphoria) are increasingly inaccessible to those in need. In the rush to address this clinical gap, some clinicians are conflating gender dysphoria with eschewing gender and/or body norms or, worse, treating body dysphoria as a body acceptance issue (which can actually boost a client’s suicidality).

Setting the Stage

Let’s back up a moment to make sure we’re all on the same page. Gender is a pervasive identity that shapes the way we move through the world. Our gender expressions influence how we talk, how we dress ourselves, and how we walk down the street. Gender assignments at birth (based solely on observable external genitalia) are often the first medical and social labels applied to a newborn infant and these legal identities profoundly shape our entire lives, especially if the assignment at birth ends up being wrong (prevalence estimates range from 0.3 percent to 2.6 percent of the population). Trans children who are given the robust message that their bodies are evidence against the self-evident truth of their gender identity develop around the daily experience of invalidation, even with the most loving of parents who may not understand the impact they’re having on their child. That so many caregivers and physicians center the conflict on the gendered body certainly factors into the development of body dysphoria (though official studies have not yet been conducted to measure this possibility).

For the past century, clinicians have used a heteronormative (assumptions of human sexual dichotomy and cisgender heterosexuality) and cissexual (assumption of body/gender congruence) lens to conceptualize body dysphoria, a practice that pathologizes transsexual gender identity. Body Psychotherapy (a developmental therapeutic approach that exploits the functional unity between mind and body) offers an approach that may be uniquely appropriate in addressing the secondary effects of body dysphoria (e.g., anxiety, social isolation, depression, and suicidality) while respecting the medical nature of the primary effects of the distress itself. TD uses a blend of different somatic perspectives and interventions, stemming from Gestalt Therapy and Christine Caldwell’s Moving Cycle,3 and allows a client to feel old pain parallel to the awareness of new possibility as the individual moves from isolation toward connection. The TD model supports the individual in managing gender/body distress by strengthening social connections, encouraging engagement in the community, and creating a practical plan for a satisfying life in the context of untreated body dysphoria and through the cultivation of solidarity with the dysphoria itself as an experience of chronic pain.

In the TD approach, management does not imply a cure or direct treatment to ease the body dysphoria itself but rather addresses the secondary effects as experienced by transsexuals who are waiting to access medically necessary treatment. The ultimate goal of a TD group is to support participants in listening to the messages of dysphoria much like one listens to the inconsolable grief of a dear friend. Rather than attempting to extinguish or dull the pain, this collaboration respects the message that “something is not right” and validates the body’s desire for corrective action. The horrifyingly high suicide rate among transgender populations underscores the urgency of need for practical, accessible, and empowering interventions. Analogous to caring for a hemorrhaging wound en route to the hospital, TD group interventions may support the preoperative transsexual who is unable to access medically necessary treatment and who must nevertheless function in professional, social, and other interpersonal spaces.

Theoretical Wallpaper

For those of us who seek to support management of gender dysphoria, it is vital to understand the trauma of being misgendered developmentally. Applying clinical theories of attachment and trauma to the trans child’s developmental experiences may offer clues to successful management of dysphoria pain. Daniel Stern revealed the developmental wounds of misattunement from caregiver to child when he described a “misstep in the dance,”4 and there can be no doubt that being misgendered by one’s dear parents or other caregivers could be a profoundly tragic misstep with regard to this fundamental social lens of gender. Stanley Keleman described the dynamic interaction between behavior and anatomy as mutually influential and emphasized that habituated states of distress result in continuous somatic patterning.5 Trans children who develop in a rigidly gendered social context may adapt to this habitual distress by forming somatic patterns that generate dissonance between identity/self-knowledge and the gendered body. As the transsexual adolescent’s body is continuously used to bolster the conflicts with their subjective experience of gender, the developing individual’s attempts to use the body to perform their felt sense of gender is sabotaged as their postures, gestures, and movement shape around the jarring experience of continuous misgendering.

Body Psychotherapeutic conceptualization of body dysphoria can assume that preoperative transsexuals experience structural organization around this insult to form as a somatic strategy to cope with the distress of the social dysphoria. Cut off from the body’s wisdom, it can become physically painful to get dressed, go out into the world, make contact with others, or generally care for the basic needs of the body. Pain is a distress message that cries out, “something is terribly wrong and needs to change!” Thierry Janssen suggests that the body’s sense of illness is an expression of experiencing imbalance and reaching for a new equilibrium.6 When preoperative transsexuals are denied access to effective treatment, they suffer not only because the new equilibrium is prevented by political policy but also because the pain message itself is pathologized, resulting in a deepening of the wound of invalidation.

If body dysphoria is the expression of conflict between one’s self-knowledge and the invalidating assignment (at birth and/or as we engage socially), then the somatic response must be to provide an appropriate therapeutic space in which the dysphoric individual might choose what it means to experience dysphoria while remaining in contact with the physical reality of the body as it actively conflicts with identity. With the support of a TD group, preoperative transsexuals can honor the message of the dysphoric body by connecting to the distress and accepting responsibility for the choice of meaning making. Non-medical interventions that inappropriately focus on body acceptance perpetuate the false idea that body dysphoria is something separate from the person.

Gestalt theories of psychological health emphasize present-tense awareness of one’s experience as a whole person in the interest of integration and meaning making. As clients become aware of what they’re doing and how they habitually do it, the seemingly chaotic parts of human experience may begin to form a powerful whole. For those who experience body dysphoria, the dominant voice of the body is one of incongruence and subsequent suffering. When preoperative transsexuals are guided to focus on what feels right and congruent in the body, they are not denying or dismissing the valid reality of dysphoria but are allowing the distress to become the background instead of the focus of experiencing life. TD grows personal integration by inviting the pain to be a valid and workable part of the dysphoric individual as a whole and vibrant being and organically seeking balance between subjective experience and physical form.

Why a group? Employing a group approach addresses the interpersonal challenges that frequently go hand in hand with navigating the world as a transsexual and may provide psychological healing through contact. Relational repair can be profoundly healing for trans folks in general due to the sadly common phenomenon of families disowning, traumatizing, and shunning members who don’t play along with the heteronormative mandates of the family system. Grouping across the six sessions, they may be able to collaborate in providing for each other a powerfully affirming container that holds more support and deeper meaning than exploring the content alone as individuals.

Lastly, I decided to base the structure of TD interventions on Christine Caldwell’s Moving Cycle, which understands healing, growth, and transformation as sequencing through four phases: Awareness, Owning, Appreciation, and Action. By engaging the physical body in support of a client’s expansion of somatic awareness and movement repertoire, the Moving Cycle offers a way to experience body dysphoria as a valid component of fully expressing one’s aliveness and provides relatively safe contact with pain and distress as a normal healthy response to incongruence. Caldwell’s model attributes tension, chronic pain, fatigue, and depression to an individual’s “unfinished experience” (in the case of dysphoria, forbidden/punished gender expression). This organic path toward integrity provides an appropriate structure for preoperative transsexuals to integrate body dysphoria as usable pain until they’re able to access medically necessary interventions.

The process of listening to the message of body dysphoria requires cultivating an inner witness to validate the self-evident nature of gender identity (Awareness), separating the reality of social injustice from the individual responsibility to create meaning and formulate a response (Owning), honoring the function of body dysphoria as a feature of each individual’s journey (Appreciation), and entering social connection with intention (Action). The predicted arc of this process moves participants from feeling limited by their pain to using the distress to expand social supports and increase their movement through communities.

Okay, enough theory, let’s get practical.

Transforming Distress in Six Modules

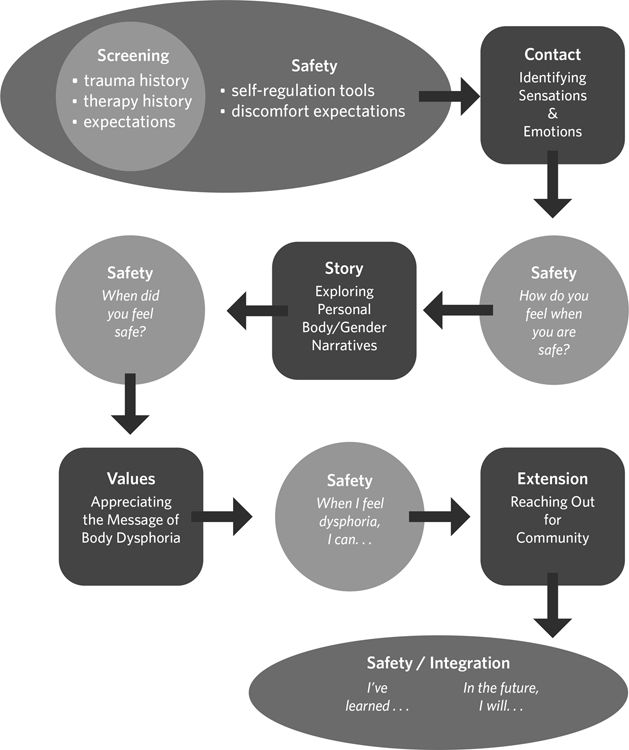

As described above, TD uses the Moving Cycle as a structure for Gestalt-informed interventions across six modules of group therapy that is specifically designed to support preoperative transsexuals in their personal goals of dysphoria management. You might notice the emphasis of creating and maintaining safety through the duration of the group. In addition to the trauma of body dysphoria itself, many transsexuals have experienced an extreme lack of physical, sexual, and emotional safety to the extent that their bodies let them know just how unwise it would be to simply assume the safety of a group (or the facilitator). To effectively use TD group interventions, facilitators must accept that safety will be gradually and carefully earned at each step. This is why I’ve decided to bookend each module and the group itself with safety-oriented interventions.

The rest of the modules follow an intentional sequence that builds on established safety to guide participants along a journey of gradually increased somatic awareness, meaning making, and empowerment. The Contact Module allows participants to learn the mechanics of checking in with the body and listening to its messages. By engaging in dialogues with the body, participants can identify different stories that the body holds in the Story Module, which provides a bridge between the murky mixture of feelings and sensations and the empowered meaning making of the Values Module. Once participants have learned to listen to the body, to locate individual power within an oppressive system, and to intentionally create new dysphoria narratives, they are ready to start inhabiting the body in the interest of collaborating with and integrating pain as a useful tool for vital social connection and creating change in their communities. Each phase places body dysphoria in the context of a whole and embodied lived experience without falling into the historical trap of invalidating the pain as general body dissatisfaction.

Getting Specific

The six-week plan for a TD group is shown in Figure 13-2 and described in the following sections.

I believe this model can be easily expanded to twelve to eighteen sessions. I doubt, on the other hand, that a condensed version would be effective, and altering this intervention to apply to individual work would undermine the empowerment found in the aspects of group work laid out in the following modules. Facilitators building a closed group should screen out potential participants who present chronic or developmental trauma in addition to basic dysphoria. However, if specifically building a group composed of those with complex post-traumatic stress disorder, I recommend extending the model to twelve or eighteen weeks and assuring a trained clinician can lead the group.

Figure 13-2: TD Group Therapy Model

Initial Safety Module

Begin

Take a few minutes for introductions and establishing group agreements (e.g., confidentiality, respectful communication, taking care of your own needs).

Focus

- Learning to track feelings of safety in the incongruent body

- Recognizing that, if we receive messages of danger (dysphoria), we are also able to receive messages of validation

Interventions

Introduce the following tips for maximizing one’s psychological safety while engaging in new (and potentially activating) content.

Do

- make contact with others when you feel safe (e.g., eye contact, distal touch, light friendly pushing, carving your movements consensually with other bodies)

- use your face and voice as expressively as you authentically can

- play with modulating your voice or animating your face

- listen to voices and separate them from background sounds, or attend to the eyes and face of speakers

- take care to give yourself what you need to feel safe (e.g., finding a quiet corner, standing to the side)

- focus (and refocus) on things you know bring you comfort or help you feel safe (take an inventory throughout all five senses)

- play musical instruments, sing, dance

- try moving toward relationships, rather than isolating yourself, when you feel slightly anxious

Don’t

- engage in heavy exercise while feeling emotionally vulnerable or having intense conversations

- isolate toward safety unless you really need to (try connecting toward safer people or places whenever possible)

- force yourself to be social—remember that it’s wise to establish safety first

- ignore your gut wisdom—learn to trust your learned sense of assessing safety

- use fighting to respond to feeling emotionally unsafe or insecure in a relationship—seek connection if it’s safe to do so and seek safety if it’s not

- forget that others need to see and feel your nonverbal expression to read your mood

- confuse distance contact (phone, internet, text) with in-person contact

- assume that, when other people are in an escalated emotional state, what they say or do reveals their “true” attitudes, opinions, or motivations

“Horsies”

This lively somatic movement intervention works to discharge stress and is particularly useful following the group sharing of heavier content. Talk participants through the natural regulation of undomesticated horses:

- First, the horse body is activated. Fully embody activation with tension, shouting, and frantic movement, and imagine a “spooked” horse running wildly through the woods.

- As soon as the horse reaches a place of relative safety, freeze and look around with wide open eyes and an open panting mouth, embodying the question, “Am I safe here?”

- Having established relative immediate safety, make horse sounds with an open, relaxed face, allowing the lips to vibrate from the forced exhale, and shake every part of the body possible from the scalp to the toes.

“Up and Out”

This intentional dissociative response to feelings of panic or stress slows participants down enough to titrate their experiences of distress. Instruct participants to lift their gaze up and out when they notice they’re overwhelmed with stress, anxiety, or panic. They can visually trace the horizon, the tops of trees, or (if unable to look outside) the line between the wall and the ceiling. By simply lifting the gaze, they can allow themselves to take a little break from the somatic experience. Tell participants to focus on exhaling longer and longer as they continue to push the gaze upward and out beyond the body.

Anger Management

Pain is an important message that “something needs to change” and is accompanied by adrenaline (energy/power to make changes), which isn’t particularly useful for creating change in social situations. Therefore, it’s important to use the muscles of the back and upper arms to discharge the activation in the body before deciding how to respond to whatever stimulates the anger. However, if we use the “punch a pillow” approach, we’re actually just reinforcing potentially harmful muscle memory: “When I’m mad, I punch.”

Common ways to discharge safely:

- Push a sturdy wall slowly, angling yourself as necessary to gain leverage. Pretend as though you’re going to push all the anger into the wall with the goal of pushing the wall over. Stop when your upper body feels a decrease in energy.

- Twist a towel—especially useful for those who need to discharge anger from a seated position. Use a large towel, such as a bath towel, to fully engage your upper body. For those who experience mild pain as relief, consider using a frozen wet towel so that the mild pain of the ice works along with the upper body movement to provide relief.

Closing

Set realistic expectations for discomfort across the arc of the group and distinguish discomfort from lack of safety. Distinguish pain from suffering and welcome pain as one of many indicators of aliveness. Be sure to validate the illusion of absolute safety for anyone, anywhere, anytime, and stress the importance of learning to carry one’s own safety to protect against vulnerability.

Contact Module

Begin

Briefly review initial safety tools. Validate the discomfort of learning new habits of response to pain or agitation. Invite participants to share relevant stories from the previous week or since the initial session.

Focus

- Identifying sensations and emotions through somatic tracking and body scanning

Interventions

Tell participants to scan for what feels painful or incongruent and to validate the pain by thanking the body. Then tell them to scan for what feels good or congruent and to affirm and validate the feeling by thanking the body. This intervention might best function as a guided meditation in the context of understanding that “what we shine a light upon grows.” In this sense, participants shine a light on congruence and affirmation without denying the pain or incongruence, resulting in forming a sort of map for where safety resides in the body. Guide participants in allowing the pain to become the backdrop for the light of what feels affirming.

Closing

Help participants document their responses to the question “How do I know when I’m safe?” by using expressive arts, such as documenting the map of what feels congruent or incongruent in the body; taking an inventory of which sensations let participants know they’re safe enough in their immediate environment; or noting emotions and thoughts that accompany these sensations.

Story Module

Begin

Briefly review safety mapping /inventory of congruence from the previous session. Validate shared experiences that refute participants’ abilities to create safety. Invite participants to share relevant stories from the previous week or since the initial session.

Focus

- Exploring personal body or gender narratives

Interventions

Divide the group into dyads and ask them to share answers to the following questions with each other:

- When did you first learn about gender?

- What did you learn?

- Who taught you?

- How did they teach you?

Be sure to allow for equal sharing in both directions by encouraging active listening without feedback and announcing timed switches.

Reconvene the larger group and encourage sharing that allows normalization of the range of caregiver experiences (from vicious and abusive to loving and well-intentioned invalidation) and contextualize the entire range: caregivers attempting to give tools for safety in a violently gendered world while also validating the harm caused by ineffective caregiving. Validate forgiveness along with lack of forgiveness as both arise.

Closing

Encourage participants to share narratives of a time when they felt safe. Revisit the question, “How did you know you were safe?” Encourage participants to explore the following questions for the next session:

- Who first affirmed your gender?

- Who in your life now affirms your identity?

- How does it feel to be witnessed with acceptance?

- What new stories do you want to tell about your body, identities, and experiences?

Values Module

Begin

Briefly check in by asking participants to share answers to the previous session’s closing questions.

Focus

- Appreciating the message of body dysphoria

Interventions

Ask participants to use expressive arts to explore or document responses to the following questions:

- When did you first recognize your experience of body dysphoria?

- When your body spoke to you then, what do you think it was saying?

- How is your body speaking to you today?

- What sensations do you experience, and what do you think your body is trying to let you know?

Reconvene the group to discuss identifying individual body messages of “what needs to change” and gradually introduce (if participants have not already alluded to it) the idea that social systems and normative stories about bodies are one part of what needs to change, letting participants know that they are not the problem.

Closing

Encourage participants to share coping strategies (i.e., “When I feel dysphoria, I can . . .”), and emphasize coping with the pain before trying to dull or end it. Work nonjudgmentally with content regarding substance abuse, self-injury, suicide, or other harmful behaviors.

Make safety plans that identify:

- warning signs, such as thoughts, sensations, emotions, or situations that let participants know dysregulation is imminent

- distraction activities, that is, what they can do by themselves to distract from the pain (e.g., listen to music, play video games, read a book)

- people to help distract from the pain, such as people in need of their own support or people with whom participants can typically just enjoy light easy fun

- people to reach out to while in pain—having exhausted attempts to distract from the pain, someone they can count on to give immediate valuable support

- professional support, such as clinicians, walk-in mental health clinics, or emergency rooms where they feel “safe enough” when all of the above has failed to offer relief—be familiar with local resources as well as national hotlines that are specifically trans informed

Be clear with your participants to what extent you are available (or not) for acute support.

Extension Module

Begin

Briefly review strategies shared in the last sessions and invite participants to review what they’ve noticed regarding management of body dysphoria since the last session.

Focus

- Reaching out for community

Interventions

Guide participants in identifying the communities they already inhabit (e.g., religious, political, familial, academic). Explore the following questions (using individual expressive art and/or dyad sharing):

- How do you inhabit these spaces as a trans person? Do you feel welcome and respected or excluded and marginalized?

- How is it similar to or different from inhabiting trans spaces?

- How do you interact with trans community members who are different from you?

- When do you feel welcomed and received by a community?

- What do you notice in your body that informs feeling respected?

- How does your body shape itself to express welcoming others?

Consider leading a movement experiential in which participants freely move around the space with ambient music and guidance as follows:

- Explore your personal space and interaction within a group.

- Feel yourself drawn to or repelled from others.

- Try on literally reaching out to others. How does it feel to reach? How does it feel to be reached to? When do you want to pull back?

Revisit the Do and Don’t lists from the Initial Safety Module as needed.

Closing

Reconvene in a closing circle and have participants anonymously write down fears, concerns, and other moments of activation during the experiential. Place folded-up writings in a bowl and have participants draw and read aloud one statement each. Have participants validate the statement by beginning their response with “That makes sense because . . .”

Invite participants to bring to the final session invitations to a community event that feels “safe enough” for fellow participants to attend together.

Safety Integration Module

Begin

Pin up a clothesline and have small cards, clothespins, and writing utensils ready. Invite participants to write the names of their communities and/or identities on a variety of cards and pin them up on the line. Have participants explore the clothesline as an inventory of all the tributaries of lineage that have pooled together to form this temporary community.

Focus

- Inviting action and engagement in communities

Interventions

Have participants create inventories that begin with “I’ve learned . . .” and “When I feel dysphoric, I can . . .”

Closing

Share community event invitations from participants in the larger group and encourage them to make plans to attend outside of the group. Invite participants to explore positions of sociopolitical location that offer a platform and ask them how to use those platforms to amplify the voices or project representation of groups that are marginalized within that space.

To Conclude

Somatic interventions that invite individuals to collaborate with body dysphoria cannot hope to ease the pain itself but can offer relief from wearing the pain as a cloak of suffering that keeps them from engaging with their communities.

Endnotes

Bibliography

Bever, Lindsey. “Transgender Boy’s Mom Sues Hospital, Saying He ‘Went into Spiral’ after Staff Called Him a Girl.” Washington Post, October 3, 2016. www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/10/03/mother-sues-hospital-for-discrimination-after-staff-kept-calling-her-transgender-son-a-girl/?utm_term=.457d01e11bc5.

Caldwell, Christine M. “The Moving Cycle: A Second Generation Dance/Movement Therapy Form.” American Journal of Dance Therapy 8, no. 2 (2016): 245–58.

Janssen, Thierry. La Maladie a-t-elle un Sens? Enquête au-delà des Croyances. Paris: Fayard, 2008.

Keleman, Stanley. Emotional Anatomy: The Structure of Experience. Berkeley, CA: Center Press, 1985.

National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force & National Center for Transgender Equality, 2010.

Sisson, Paul. “Mother Sues Rady Children’s for Allegedly Insensitive Transgender Care.” San Diego Union Tribune, September 26, 2016. www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/health/sd-me-transgender-lawsuit-20160926-story.html.

Stern, Daniel. The First Relationship: Infant and Mother. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977.