There are many ways that the history of both the United States and the world might have been different had not a strange man named Leon Czolgosz, using a pistol concealed by a handkerchief, shot President William McKinley twice in the abdomen on September 6, 1901, while shaking his hand at the Temple of Music in Buffalo. This much is certain: American economic history changed decisively in that moment.

Under President McKinley, laissez-faire was the unannounced, but nonetheless evident, economic policy of the United States. As biographer Edmund Morris puts it, McKinley “tacitly acknowledged that Wall Street, rather than the White House, had executive control of the economy.… This conservative alliance, forged after the Civil War, was intended to last well into the new century, if not forever.” The doctrine of laissez-faire, a cousin to Social Darwinism, suggested that economic problems would tend to work themselves out, and hence government intervention would usually do more harm than good. Its American translation was, “Let well enough alone!” That was the faith, and as such it took on Constitutional dimensions. For it dictated that not even Congress or elected representatives were to “interfere” with the economy; the economy had its own sovereignty. Laws seeking to ban child labor, or set maximum work hours were, by this thinking, unconstitutional intrusions into the economy’s natural operation.*

McKinley’s laissez-faire views had left the Sherman Act, then a newly enacted antitrust law, in a stillbirth from which it was not clear it would ever emerge. Men like McKinley took the law as merely symbolic, a resolution meant to appease the populist wings of both parties. Others thought it simply reaffirmed pre-existing practices of the courts, and hence did not change anything. McKinley’s main concession to growing public arousal and unrest in the late 1890s was to discuss the “Trust problem” in one State of the Union speech, and suggest it was something Congress really ought to deal with some day. It was as if the Sherman Act did not exist.

That impression was only confirmed, in 1901, when it became known that J. P. Morgan was now planning to buy out Andrew Carnegie and create the U.S. Steel trust. While it was a flagrant violation of the Sherman Act, the McKinley White House offered no public comment and instead held a dinner in Morgan’s honor.

But now President McKinley lay dying, suffering from gangrene, after surgeons failed to locate the bullet lodged in his body. A firsthand report of Morgan’s reaction to the news of McKinley’s shooting has him seizing the arm of the reporter from the New York Times: “What?” and then slumping into a desk chair, exclaiming: “This is sad, sad, very sad news.” Upon his death, Senator Mark Hanna, one of McKinley’s closest friends and conservative allies, publicly declaimed, “Now look—that damned cowboy is President of the United States!” And Morgan was right to be concerned, for the death of McKinley did change everything, putting economic policy in the hands of an entirely different kind of man.

Theodore Roosevelt may not need a full introduction. He was born to a wealthy family, but was a man whose democratic leanings were unmistakable. In his storied career, in his rise from New York City police commissioner to Assistant Secretary of the Navy to the Presidency, he managed to combine an imperial temperament with an ear for public sentiment. He was not anti-business, but strongly insistent on punishing villainy when he saw it, and most of all he believed that a majoritarian government must lead the country. His determination that the public was ruler over the corporation, and not vice versa, would make him the single most important advocate of a political antitrust law.

Roosevelt’s revolt and rejection of laissez-faire was actually evident two weeks before McKinley’s assassination. He gave a landmark speech in Minnesota asserting that it was time for the State to assert its authority over the trusts. “The vast individual and corporate fortunes, the vast combinations of capital which have marked the development of our industrial system,” he said, “create new conditions, and necessitate a change from the old attitude of the State and the nation toward property.”

But Roosevelt’s legacy lies not merely in his rhetoric. A law like the Sherman Act is, without enforcement, a dead letter. That’s why a focus on enforcement of the law is so critical to the story of the war against the trusts. And here Roosevelt was not a man to content to play around at the edges. As president, he would soon directly confront the two greatest monopolists of the age, who were the very backbone of the trust movement—J. P. Morgan, and then John D. Rockefeller—in what can only be described as acts of enormous courage.

His offensive against Morgan came first, and it was sparked by the latter’s railroad monopolization. In 1901, at just about the time Roosevelt was taking the presidency, Morgan and another railroad magnate, James J. Hill, were effecting the monopolization of Western railroad transportation. Morgan forged a truce among former rivals (including Rockefeller), embodied in a new trust, the Northern Securities Company, representing a new, unified monopoly over all of the Western railroads, instantiated in a New Jersey Trust corporation. It was what is today called a “merger to monopoly” and clearly violated the Sherman Act.

Had he still been in power, President McKinley would almost certainly have “let well enough alone,” as he had the U.S. Steel merger, or perhaps asked Morgan, in confidence, for a few concessions. But Roosevelt, in one of his first main actions as president, ordered his Attorney General Philander Knox to begin an investigation of the Northern Securities Company, and to review its legality under the Sherman Act. Knox, perhaps prodded by Roosevelt, stunned the political and financial world with an announcement: “In my judgment, [the Northern Securities Company] violates the provisions of the Sherman Act of 1890.”

Why did Roosevelt order the investigation? Roosevelt was far less wary of size as a danger unto itself than a man like Brandeis. He held a real affection for the greatness and majesty of large institutions. Nor did he hold a personal animus toward Morgan himself—they were both of the New York aristocracy, and he’d personally invited Morgan to White House dinners.

For Roosevelt it was a matter of political democracy. He plainly saw the growing power of the trusts as a serious political question, as a threat to the basic proposition of democratic rule. To Roosevelt, economic policy did not form an exception to popular rule, and he viewed the seizure of economic policy by Wall Street and trust management as a serious corruption of the democratic system. He also understood, as we should today, that ignoring economic misery and refusing to give the public what they wanted would drive a demand for more extreme solutions, like Marxist or anarchist revolution. Hence, as he later said, “When aggregated wealth demands what is unfair, its immense power can be met only by the still greater power of the people as a whole.” And, as he wrote to a friend at the time, “the absolutely vital question” was whether “the government has the power to control the trusts.”

A few weeks after Knox’s determination, at the direction of Roosevelt and his cabinet, the United States filed suit against the Northern Securities Company, beginning the first great judicial attack, by the federal government, on a private trust and on the personal economic power of J. P. Morgan himself.

Later in life, Roosevelt would give his account of Morgan’s reaction.* Soon after suit was filed, an indignant and angry Morgan arrived at the White House and demanded to see the president. He was granted an audience, where Morgan complained of the lack of notice, and proposed that their lawyers meet to settle the matter. “If we have done anything wrong,” said Morgan, “send your man to my man and they can fix it up.” But Roosevelt responded, “that can’t be done,” and Knox added, “we don’t want to fix it up, we want to stop it.” Morgan, quietly furious at the challenge to his power, demanded to know whether his prize creation, U.S. Steel, would also be coming under attack. “Certainly not,” said Roosevelt, “unless we find out that in any case they’ve done something we regard as wrong.” When Morgan had left, Roosevelt summarized the meeting this way: “Mr. Morgan could not help regarding me as a big rival operator who either intended to ruin all his interests or could be induced to come to an agreement.”

It was at around this time that the word “trust-buster” (and its occasional synonym, “octopus hunter”) came into widespread popular usage. It became Roosevelt’s appellation; he became the trustbuster incarnate. It was the image inhabited by Roosevelt in print and editorial cartoons, given color by the President’s bold declarations. Over the summer of 1902, during the campaign against Morgan, he gave a speech in Rhode Island where he announced that “a man of great wealth who does not use that wealth decently is, in a peculiar sense, a menace to the community.” He added that the “trusts are the creatures of the State, and the State not only has the right to control them, but it is in duty bound to control them wherever need of such control is shown.”

And so here begins the trust-busting tradition in its hour of greatest glory. Its significance cannot be overstated. A law like the Sherman Act, like the Constitution, is so broadly worded and unclear in its application that it does not take real meaning or shape without an enforcement tradition. In the person of Roosevelt was born the archetype: the courageous government official unafraid of the massive private power represented by the trusts, the incorruptible sheriff of economic justice. As the Washington Star put it, “The President of the United States is the original ‘trust-buster,’ the great and only one for this occasion.”

In the century to follow, the trustbuster mantle would be something like a magic cape, or perhaps suit of armor, emboldening its wearer, that would be passed down through the generations. It would be inhabited first by Taft, Roosevelt’s successor, who was even more aggressive that Roosevelt. It would be worn by prominent Justice Department officials, including, among others, Robert Jackson, who would also be a Nuremberg prosecutor, and by Supreme Court Justice Thurman Arnold, the Wyoming “cowboy” and Yale professor who became the New Deal’s most aggressive trustbuster. It also belonged to Joel Klein, who in the 1990s faced off with Bill Gates.

Along with the mantle and the archetype came a tradition, one that lasted at least to the 1990s, of bringing “battleship” cases against giant, industry-spanning monopolists. These declarations of war against giant firms were not for the faint of heart. The cases could last years, if not decades, and demand resources that strained even the richest government on Earth. They also tended to yield political attacks and efforts to ruin government agencies like the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission, not to mention personal attacks as well.

The Northern Securities litigation itself went relatively quickly: The Justice Department asserted that the establishment of the firm was an attempt to monopolize the railroad business, in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act. The company’s main defense was that the federal government had no authority to stop its mergers; it had no right to punish the mere transfer of property and establishment of a new state corporation. In the alternate, it responded that its goals were, in fact, entirely beneficent: It wished to enhance and extend commerce across the West, and benefit the public through a better railroad.

After two full trials (one contested by Minnesota), the case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court. In a major victory for Roosevelt, the antitrust law, and the Congress of 1890, the merger was blocked. The opinion was written by Justice John Marshall Harlan, a great antitrust absolutist, who spoke for the agrarian and populist spirit behind the Sherman Act’s creation, and would become a leading judicial voice supporting the early trust-busting tradition.

Harlan read the Sherman Act as a literal ban on trusts, which, as he would later say, presented the danger of a “slavery that would result from aggregations of capital in the hands of a few individuals and corporations.” With the Northern Securities opinion he effectively awoke the Sherman Act’s anti-monopoly powers. For him, the western railroad trust was a blatant violation of the Sherman Act’s prohibitions. For it “placed the control of the two roads in the hands of a single person, to wit, the Securities Company, … [and] destroy[ed] every motive for competition between two roads … by pooling the earnings of the two roads for the common benefit of the stockholders of both companies.”

Despite Harlan’s certainty, the decision was a close one, won on a 5–4 vote, and the famous dissenter, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, took the view that the Sherman Act was not, in fact, meant to outlaw the trusts or even to protect competition. Instead, according to Holmes, “it was the ferocious extreme of competition with others, not the cessation of competition among the partners, that was the evil feared.” In other words, Holmes held the bizarre idea that ruinous competition was the concern of the Sherman Act, a theory hard to square with its text or history.*

In the end, Northern Securities was an important victory for Roosevelt and his premise that the trusts must obey the state, for he had challenged and humbled a man, J. P. Morgan, who had once seemed beyond the reach of any law, a man who nations might obey rather than order. As Roosevelt later reflected, “it was imperative to teach the masters of the biggest corporations in the land that they were not, and would not be permitted to regard themselves as, above the law.”

Political Antitrust

When Roosevelt activated the Sherman Act, his goal was as much political as economic. He saw enforcement of the Act as essential to making clear that, in a democracy, the elected representatives ultimately had the final say, and saw the antitrust laws as one antidote to danger of private economic power that might rival public power. As Justice William Douglas would later put it, “power that controls the economy should be in the hands of elected representatives of the people, not in the hands of an industrial oligarchy.” Hence the idea that antitrust would play a Constitutional role.

But what does it mean to say that antitrust plays a “Constitutional” role? As every American schoolchild knows, the U.S. Constitution is comprised of a system of checks and balances. The legislature is supposed to check executive power, and vice versa; the judiciary provides checks on the legislature, the executives, and the states as well. Hence, antitrust law was serving as a new kind of limit: a check on private power, by preventing the growth of monopoly corporations into something that might transcend the power of elected government to control. His pursuit of this goal makes it fair to call Roosevelt the pioneer of political antitrust.

In our times, when concerns about corporate influence over government have reached a fever pitch, the political importance of antitrust as a check on private power might seem more obvious than ever. Yet over the last few decades, the very idea of political role has all but disappeared, as antitrust’s focus has become exclusively and narrowly economic. It isn’t as if the laws have been amended: The legislatures repeatedly expressed fear and concern with the accumulation of private power in competition with government. As recently as 1962, the Supreme Court pointed out that the antitrust laws respond to a “concentration of economic power” and also a “threat to other values,” like the independence of smaller businesses or local control of industry. The retreat, rather, is best attributed to a combination of fear and uncertainty among those who enforce and interpret the laws—especially departments of government and federal judges. Political values, the argument goes, are just, well, too political or too vague to be considered part of enforcement policy.

This is not a good excuse. No one denies that economic considerations are what should govern any individual case. But the broad tenor of antitrust enforcement—the broader goals of enforcement—should be animated by a concern that too much concentrated economic power will translate into too much political power, and thereby threaten the Constitutional structure. Or, as Robert Pitofsky put it, we should always be concerned that “excessive concentration of economic power will breed antidemocratic political pressures.”

Let’s make plain what both Roosevelt and Pitofsky noticed: The compatibility of extreme industrial concentration and democratic government is an uncertain proposition. At some level the point is obvious: Private economic power is a rival to the power of elected governments, and firms may also seek to control politics for their own purposes. Increased industrial concentration predictably yields increased influence over political outcomes for corporations and business interests, as opposed to citizens or the public. But let us take a moment to see how political scientists have developed this point.

In a representative democracy, lawmaking is supposed to roughly match what the majority wants. If that is unclear or disputed, then we might expect or hope they’d reflect the interests of the “swing” voter—that is, the middle-of-the-road man or woman. But research shows that, for the vast majority of policy matters, that isn’t how things work at all.

It was a scholar named Mancur Olson at Harvard who, in the 1960s, upended the understanding of political influence by pointing out that, in fact, large majorities don’t get what they want on many issues. Instead, they consistently lose out to small, closely-knit groups with discrete interests around which they organize—of which the “industry association” is the best example. A group like “the middle class” or “consumers,” while impressive in numbers and even theoretical economic power, faces major disadvantages in the actual political process. That follows because political influence—lobbying—requires organization, financial resources, time, and yields rewards that are not limited to those who put in the effort. Olson’s memorable conclusion is that the small and organized will dominate the large and disorganized.

There are always a few inspired members of the public who devote their lives to political change. But their numbers pale in comparison to the paid ranks of corporate lobbyists, working at industry organizations, whose incentive is not altruism but generous salaries for achieving payouts through lawmaking. If one simply regards lobbying as an investment in political outcomes, the rewards are copious, and more than justify the money and effort. Consider, for example, the case of the pharmaceutical industry in the United States. In 2003, the industry invested $116 million in convincing Congress to ban America’s largest federal-run insurance program, Medicare, from negotiating for lower drug prices. That $116 million was, to be sure, a major investment. However, the enactment of the negotiation ban has benefited the industry (and cost consumers) an estimated $90 billion per year. As an investment, it returns some 77,500 percent, and is a gift that keeps on giving. In recent years, when President Donald Trump, in a populist mood, proposed changing the law and forcing negotiations, the money began to flow, and lo and behold, the proposal went away.

Everyone knows that lobbying works. But a key and neglected point is that the relative consolidation of industry has an important influence on it. That follows because the fewer members of the industry, the fewer among whom the gains are split. Take the industry organization “Airlines for America.” It has a limited number of members—three major airlines and seven smaller ones. The fruits of any policy success—say, preventing a cap on baggage and change fees—are immediately shared among the members.

Concentrated industries have good reasons to invest political influence. Consider, by contrast, the problem of collective action that faces “the middle class,” a large group with some 100 million members. A middle-class tax cut might save each member $500 a year. However, it might also require someone to invest $50 million to lobby and ensure passage of that tax cut. As the math makes clear, there is no individual member of the middle class that has the incentive to make that investment. Even if it were just a $20 million lobbying price tag, there would still be no investment. This is the problem of collective action, and it predicts that large groups—the majority—will often be losers in the legislative process.

Advanced empirical research has begun to demonstrate that these predictions bear out. A Princeton and Northwestern group in 2014 tested various theories of politics and concluded that a theory of “biased pluralism” best explained outcomes—that the public policies “tend to tilt toward the wishes of corporations and business and professional associations.”

How does antitrust’s approach to concentration relate to this? Simply enough: The more concentrated the industry, the fewer who need to coordinate, and the fewer among whom the stakes need be divided. If an industry has sixty or eighty firms in it, they may squabble, be incapable of acting as a group, and also face the problem of collective action. But, after consolidation, we might be speaking of just six firms, and the prospects for political cooperation improve. And after a merger to monopoly, there is no need to cooperate at all.

The simplest—if slightly overstated—way to put this is as follows. The more concentrated the industry, the more corrupted we can expect the political process to be. Here, by corrupted, we mean a political system that does not serve its stated goals—service of the public’s interests—but instead favors a few groups at the expense of the general public.

All of this amounts to just a more fancy way of demonstrating Roosevelt’s point: Concentrated private power can serve as a threat to the Constitutional design, and the enforcement of the antitrust law can provide a final check on private power. This, by itself, provides an independent rationale for enforcement of the antitrust laws.

The Abusive Trust

Roosevelt’s confrontation with J. P. Morgan’s western railroad monopoly in 1904 was neither timid nor trivial. But if blocking the formation of a new monopoly trust was one thing, what about all the trusts that were already running the economy? To put the question more bluntly, what about Standard Oil?

For there, unmolested, sat Standard Oil, the very first trust. It held its monopoly for nearly twenty-five years. At the time, it was the largest private firm in the world. Standard Oil’s patriarch, John D. Rockefeller, was in fact the wealthiest single American in history, with an accumulated capital between $300 and $400 billion in today’s dollars.

Quite a feat for a man born poor, to a father who was little more than a confidence man. Once upon a time, in the late 1860s, “the Standard” had been just a mid-sized Cleveland operation with no particular technological advantages over its rivals. It did, however, have the strategic genius of Rockefeller and his particular talent for industry conquest. As journalist Ida Tarbell would write of him, Rockefeller “was like a general who, besieging a city surrounded by fortified hills, views from a balloon the whole great field, and see how, this point taken, that must fall; this hill reached, that fort is commanded. And nothing was too small: the corner grocery in Browntown, the humble refining still on Oil Creek, the shortest private pipe line. Nothing, for little things grow.”

For more than two decades Standard Oil had batted aside any would-be challengers with a mixture of strategies and tactics that would have made Sun Tzu nod his head in approval. In this respect, the Standard was actually in a slightly a different category than the trusts built by J. P. Morgan. If Morgan used carrots—splitting the proceeds of monopoly—Rockefeller preferred a big stick—the exclusionary cartel, ruinous railroad prices, predatory refining prices, and the passage of laws designed to exclude any would-be competitor. Rockefeller liked to offer his smaller rivals the choice first popularized by Genghis Khan: Join the empire, or face complete destruction.

In fact, the continued existence of Standard Oil threatened to make a mockery of the antitrust law. For if the law would tolerate Standard Oil, the original trust, an abusive monopoly, how could it be said to be an “anti” trust law at all?

Roosevelt, as we’ve said, was determined to demonstrate that government was sovereign over even the mightiest corporations, even Standard Oil. But Roosevelt was politically savvy enough to understand that he needed an angle. His opportunity was created by the publication, in 1904, of a sensational and widely read history of Standard Oil in McClure’s magazine by reporter Ida Tarbell.

The History of the Standard Oil Company, nineteen parts in total, was a product of extensive reporting, and it told the full story of both Standard Oil’s rise to power and its quashing of threats to its rule. Carefully researched and written in a balanced fashion, yet dark in its implications, the series reached a large audience and provoked national outrage. Tarbell discovered and documented previously unknown abuses—particularly, in the use of railroad rates—and revealed a certain darkness at the heart of the trust. Here is an example of an exchange she published:

“But we don’t want to sell,” objected Mr. Hanna [an independent refiner.]

“You can never make any more money, in my judgment,” said Mr. Rockefeller. “You can’t compete with the Standard. We have all the large refineries now. If you refuse to sell, it will end in your being crushed.”

Among the objections to the Trust movement, as we’ve seen with Brandeis, was the observation that the drive to bigness and monopoly also seemed inevitably to come with its own morality, one that either displaced or replaced Christian or other moral strictures, at least for matters of business. But the drives toward monopoly were rough affairs, inevitably demanding a departure from practices previously considered moral or ethical in personal dealings. They tended to involve deception, bribery, and manipulation, and at worst, sabotage, bankrupting of rivals, and even the killing of workers to quell unrest.

The trusts seemed to come with a new system—a “dual morality,” which arguably came to its fullest flower later in the writings of novelist Ayn Rand. It was a morality that would come to celebrate brutality in commerce, and the holding of one set of ethical or moral rules for personal dealings, and another very different set of rules for business. Indeed they were sometimes quite the opposite: The more extreme the piety of personal views, the more extreme the commercial abuses.

Tarbell noticed exactly this tendency in John D. Rockefeller. As she wrote “there was no more faithful baptist in Cleveland than he … He gave to its poor. He visited its sick.” And yet “he was willing to strain every nerve … to ruin every man in the oil business.” She felt that “religious emotion and sentiments of charity … seem to have taken the place in him of notions of justice and regard for the rights of others.”

The split personality characteristic of this dual morality was if anything more acute in J. P. Morgan. “A man always has two reasons for the things he does,” Morgan once told an associate. “A good one and the real one.” At home in New York, he was a pious family man who attended church twice on Sundays. He was the senior warden of St. George’s Church in Manhattan, and in his will he described his soul as free of sin. Yet while overseas or aboard his massive steamship yacht, The Corsair, he seemed to adopt a completely different set of ethics, enjoying cruder pursuits, cutting secret deals to bankrupt rivals, bribing government officials, and enriching himself and friends. He also enjoyed a steady stream of female visitors on his ship, and maintained a well-documented collection of mistresses, many of whom seem to have been well-compensated for their attention to such a strikingly ugly man. At times, he seemed to have more freely mixed his interests in religion with his playboy lifestyle. While cruising down the Nile at age seventy-four, his “party had included, characteristically, a bishop and several attractive ladies.” The latter (and maybe the former) he showered with gold jewelry purchased in Cairo—“help yourselves,” he said.

Times have not changed so much, and business magnates do not stand alone in compartmentalizing their morality. But what was new were the lengths taken to justify certain conduct, as opposed to hiding it, making the unethical into the necessary, indeed the proper.

The revelation of Standard Oil’s abuses was particularly important for Roosevelt and his approach to enforcement. For the story of Roosevelt the trustbuster is the simple story, and the simple story is sometimes the more important one. It unquestionably describes Roosevelt in his first term. But as we have hinted, Roosevelt was, in fact, far more conflicted about the antitrust laws then he liked to let on. For while thought that the trusts needed to brought to heel, made accountable to the public, he also worshiped size and power as much as any man. The early Roosevelt made peace with his internal contradictions using a simple but vitally important distinction: a line between the “bad trusts” and the “good trusts.” In other words, he would bust only the bad trusts, those engaged in abuse of competitors, corruption of politic process, and general villainy. But, as he put it “we grudge no man a fortune which represents his own power and sagacity” he said, if “exercised with entire regard to the welfare of his fellows.…”*

Given an opening by Tarbell, and with the patience of a hunter, President Roosevelt directed his newly created Bureau of Corporations (the predecessor of the Federal Trade Commission) to investigate Standard Oil’s practices. After two years of fact-finding, Roosevelt transmitted a report to Congress, echoing Tarbell’s findings but going deeper, offering a damning account of abuse of competitors over a long time. Having cornered his opponent, Roosevelt announced that his Justice Department would now be taking up the question of prosecution.

What had Standard Oil done, according to investigators and the courts? While the record is lengthy, we can concentrate on two main periods. Over the 1870s Rockefeller monopolized oil refining, and did so not just by growing, but through a mixture of exclusionary cartels, the leverage of railroad pricing power, and a bold program of acquisitions. Rockefeller began by banding together with the other large refiners in Cleveland and Pittsburgh, and they collectively struck a deal with the major railroads that guaranteed lower rates for their shipments while fixing prices higher for anyone out of the club—that is, would-be independents or smaller competitors.* This part of his strategy exactly reflects today’s battles over Net Neutrality, for Rockefeller used the key economic network of his time (the railroads) to ensure a major disadvantage for his smaller rivals. The cartel system was discovered and illegalized, but Rockefeller and his allies turned to secret “rebates” on railroad prices with the same effect. Eventually most of the states and the federal government enacted common carriage law, which mandated charging standardized carriage rates, but Standard Oil still found ways to secretly violate the law.

The exclusionary railroad cartel had more than one purpose, for it also served as a club. Rockefeller embarked on an industry shakeout, using the threat of higher railroad rates to begin forcing smaller refineries to sell out to him at a loss. Once he’d bought out his smaller rivals, he turned on his larger partners as well, bringing them all into a single trust under his control. In just over a decade, Rockefeller drove the market share of Standard Oil from 10 percent to over 90 percent.

Building a monopoly is one thing, but Standard Oil then managed to defend the monopoly and its profits for the next thirty years, even in the face of disruptive new technologies, like the oil pipeline, which, as many important technologies do, threatened to bring new competition and lower prices to the industry. Rockefeller identified and met the challenge of pipelines directly, by building his own and ensuring the ruin of his new pipeline challengers. He prevented many pipelines from being built in the first place, or bankrupted and acquired those that managed to be built, a process that tended to scare off would-be competitors. Among the tactics used to keep competitors at bay were regionalized pricing strategies (strategically overpaying for crude in some markets, lowering prices in others), and the assertion of political influence, such as ensuring that government would prevent rival pipelines from getting the rights-of-way they might need or even banning competing pipelines altogether. Contrary to revisionist history, “predatory pricing” was not the only or the main method used by Standard Oil; it mastered the many ways of fighting dirty to keep its grip on the industry.*

Armed with copious evidence of these various abuses and exclusions, the Justice Department filed a 170-page complaint in 1906. Among various behaviors indicted were the exclusive cartel deals with the railroads, abuse of its pipeline monopoly, and predatory pricing—conduct that, to the ears of a contemporary antitrust lawyer, violates the ban on monopolization (Section 2 of the Sherman Act), and restraints on trade (Section 1 of the Sherman Act).

With this the stage was set, but one thing is important to know, for it portended the future. Roosevelt, just before pulling the trigger, summoned Standard Oil’s leadership to the White House for a secret meeting. There he put a different option into consideration: Might the world’s largest oil company be willing to accept government oversight, promise to clean up their act, and even, perhaps, become the first “public” trust?

This offer reflected the fact that Roosevelt’s primary concern was not so much decentralization, but the supremacy of elected government. It was an interesting possibility—imagine the United States government in active control of the world’s largest oil company, now reformed to serve as a public utility. In some ways, it might have made the United States more like Saudi Arabia, where Saudi Aramco, the state-controlled oil company, forms a major part of the economy, and currently has an estimated value of some $1.4 to $2.1 trillion (in comparison, Apple, the world’s most valuable public company, is worth $1 trillion). But this alternative history was not to pass, because Standard Oil rebuffed him entirely. It would be many years until another firm said “yes” to a similar offer—AT&T, the telephone monopolist. In any case, facing mounting evidence of villainy, Roosevelt adjudged Standard Oil to be what he called a “bad trust” and decided it was time, again, to go to war.

In the summer of 1906, President Roosevelt and the cabinet unanimously agreed to bring suit against Standard Oil. By that time, Standard Oil also faced a flurry of state antitrust actions, as well as an investigation into railroad rate manipulation that made criminal prosecution possible. The case went to trial, and 1,371 exhibitions were entered into evidence, while the government called 444 witnesses. The lower courts adjudged Standard Oil guilty, and faced with overwhelming evidence, it was not particularly hard for the Supreme Court to conclude in 1911 that Standard Oil was the kind of abusive and anti-competitive trust that the Sherman Act had been designed to illegalize. The Court, most importantly, affirmed the remedy: a breakup of the firm into some 34 constituent parts.

Among scholars, and among its critics, the Supreme Court’s decision is usually remarked upon for its implication that only “unreasonable” restraints of trade or combinations were illegal. That dictum was undoubtedly important. It set up one of the greatest questions for antitrust: are all monopolies forbidden, or only the “abusive” among them? In Roosevelt’s usage, did the law ban all trusts, or just “bad trusts?” But this much was clear: A monopoly with a track record of exclusion and abuse like Standard Oil warranted the dissolution of the firm.

Justice Harlan concurred in the dissolution of Standard Oil, but was incensed by the Court’s implicit holding that a “reasonable” conduct might not be condemned. In memorable fashion, he restated the origins and purposes of the Sherman Act:

All who recall the condition of the country in 1890 will remember that there was everywhere, among the people generally, a deep feeling of unrest. The nation had been rid of human slavery, fortunately, as all now feel—but the conviction was universal that the country was in real danger from another kind of slavery sought to be fastened on the American people; namely, the slavery that would result from aggregations of capital in the hands of a few individuals and corporations controlling, for their own profit and advantage exclusively, the entire business of the country, including the production and sale of the necessaries of life. Such a danger was thought to be then imminent, and all felt that it must be met firmly and by such statutory regulations as would adequately protect the people against oppression and wrong.

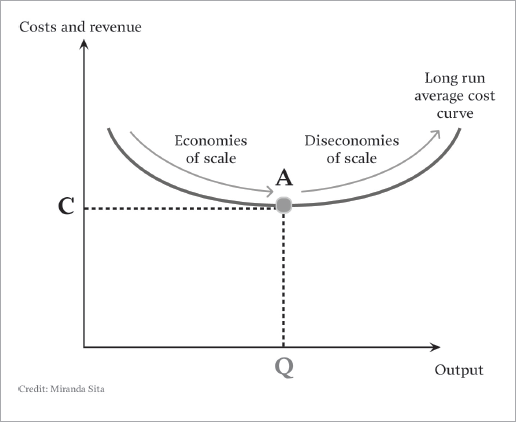

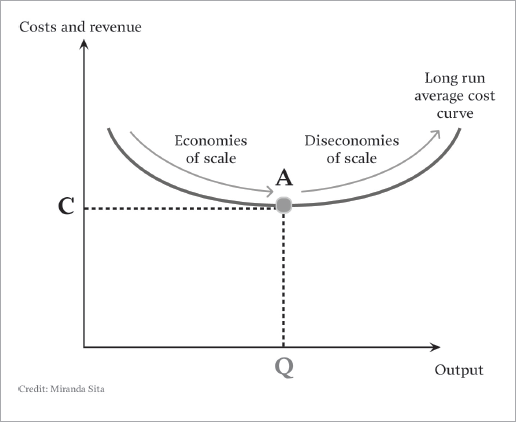

Economies and Diseconomies of Scale

Standard Oil was broken into its constituents parts, among them seven “majors,” many of which remain among the most valuable and powerful firms on Earth, including, notably, Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon), Standard Oil of New York (Mobil), and Standard Oil of California (Chevron). In the aftermath of the breakup, stock was divided proportionately, and, to the surprise of many observers, within a year, the value of what had been Standard Oil had doubled, and in several years, had increased five-fold.

The story of Standard Oil raises what is perhaps the central economic question we shall confront. The proponents of the trust argued that their size and monopoly control was natural and necessary: that the larger firm was simply more efficient than the small operators of old. The economic phrase that captures this idea is that of “economies of scale,” and it simply suggests that larger producers will outperform smaller ones. If this is true, is the whole enterprise of antitrust and decentralization misguided?

Let us examine this question carefully. It is true that a large factory, operating at volume, will usually produce goods at lower cost than a mom-and-pop operation. That’s why cars are produced on large assembly lines, not at the neighborhood craft automobile manufacturer. It is something also witnessed in the tech world. In the age of Amazon and Google it often seems that the company which has the most servers or collects the most data necessarily has the better product.

But the economics of the last century have made it clear that the basic proposition—that bigger is better—is subject to both limitations and caveats that make the full picture complex. First, at some point, economies of scale “run out”—that is, increasing size no longer creates further efficiencies. A car plant needs to be a certain size to be efficient, but after that, it no longer becomes any more efficient. That point varies by product and industry. Making pizza efficiently requires little more than an industrial oven, giving a massive operation no efficiency advantage over a neighborhood store. The advantages, if any, are those related to size, power, reputation, and so on—compare the Domino’s chain to the local pizzeria—but are not actually related to the ability to make a better product.

The size problem is made more complex by two more factors. One is that as the size of the operation increases, “dis-economies” of scale begin to creep in, as economists since Alfred Marshall in the 1920s have suggested. For example, as a firm adds more and more employees, it needs to add more managers, and ever-more complex systems of internal control, which tend, at some point, to begin making the firm less efficient. Managers in larger firms may start to yield to the temptations of seeking their own personal enrichment and power as opposed to the interests of the firm. Sometimes great size yields a short-term advantage, but creates “dynamic” disadvantages: A larger firm may also become cumbersome, unable to adapt to changing market conditions. Consider that General Motors was thought a paragon of efficiency in the 1950s, but by the 1980s had become an unwieldy monster that eventually went bankrupt.

Hence the premise that productive efficiency usually has a U-shaped relationship with scale, as pictured here:

This is the curse of bigness illustrated. The point is intuitive to anyone who has actually worked in an enormous organization of some age and wondered where the phrase “efficiencies of scale” could have come from. As business tycoon T. Boone Pickens once put it, “It’s unusual to find a large corporation that’s efficient. I know about economies of scale and all the other advantages that are supposed to come with size. But when you get an inside look, it’s easy to see how inefficient big business really is.”*

It was these creeping inefficiencies in sprawling firms that Brandeis thought of as comprising part of the curse of bigness. But there is another side to the curse, one associated with growing power. It is this: As a business gets larger, it begins to enjoy a different kind of advantages having less to do with efficiencies of operation, and more to do with its ability to wield economic and political power, by itself or conjunction with others. In other words, a firm may not actually become more efficient as it gets larger, but may become better at raising prices or keeping out competitors.

The large firm, alone or in cooperation, can and usually does invest in “moats”—the business school term for barriers that are designed to keep out new competitors who might have better-quality products or cheaper prices. There are myriad methods of doing so—like control of scarce resources, exclusive or preferential deals with retailers or distributors, government licenses, and so.

Meanwhile, the growth of individual firms through mergers usually correlates with increased “concentration”—that is, fewer firms in the industry. And once an industry is composed of just a few majors, it becomes easier for them to jointly extract a cost to society. The easy way is by coordinating on higher prices. The fewer members in the industry, the easier it is to cooperate on building a “joint moat”—perhaps the “walled city” is a better metaphor—designed to keep out any would-be invaders. Finally, as we have seen, giant firms, often in cooperation with their counterparts, have great incentives to invest in the political process to obtain the passage of laws that either fortify the moat or just transfer wealth to the industry, like tax cuts or subsidies.

The effects of size and concentration are not limited to mere self-preservation. The larger and more powerful firm has a clearer bargaining advantage over its workers; the monopolist most of all. Back in the nineteenth century, the power of large firms enabled them to drive workers harder and longer, for less money, and also provided the resources to break unions with violent attacks, sometimes by even hiring their own armed militias. Today, concentrated economic power is used to avoid raising wages, to insist on intense conditions of employment, to abuse of “non-compete” agreements, and to hire part-timers instead of full-time employees. The more power a firm or industry enjoys, the easier it is to prevent employees from getting too much of the returns.

To be sure, there are some private checks on bigness, or of the building of empire for empire’s sake. The firm’s owners or board of directors may order management to stop expanding for no good reason but their own welfare. Smaller, more efficient competitors do sometimes manage to kill a bloated dinosaur, or the firm may be taken over by a corporate raider who sees value in breaking the firm into smaller pieces. But unfortunately, these market-based checks on bigness can and do fail, and their mythology can outmatch their real effectiveness. For they are, at all times, counterbalanced by the advantages and attractions of power, and the allure of monopoly profit. For that reason, oversized, inefficient firms can persist for decades, effectively immunized from the need to improve products or lower prices. Instead, like American domestic airlines, the industry can happily offer a product that continues to get worse and cost more.

That monopoly can be an inefficient form was a lesson from the Standard Oil case, for in the end, the breakup of the oil industry was a boon to its further expansion. That isn’t unusual: the break-up of the original film-trust sparked the rise of the American film industry; and in more recent times the campaigns against AT&T and IBM sparked a momentous boom in the telecommunications and computing industries. The cries of doom, gloom and economic catastrophe are often overblown, for some industries can benefit from a breakup. Indeed, as the example of the Standard suggests, while the patient may protest, the government is sometimes doing it a favor.

Antitrust’s Constitutional Moment

Roosevelt’s cases against Standard Oil and J. P. Morgan were his most dramatic; but in total, he filed forty-five cases and achieved numerous breakups. The trustbusting campaign continued under his successor, President William Howard Taft, who pursued a total of seventy-five cases, including cases targeting U.S. Steel and AT&T, two of J. P. Morgan’s other creations. By the end of the 1910s, just about every one of the major trusts had been broken into pieces or had some encounter with the antitrust law, making it, for a while at least, a primary level of federal economic policymaking. In this sense Roosevelt achieved his goal—demonstrating the primacy of the elected government over the structure of the economy.

However, as we’ve already said, Roosevelt’s views of monopoly and size were more complex that the trustbuster moniker allows. He had an incurable admiration for that which was grand, mighty, and powerful, like the new U.S. Navy he helped build. He could not help feeling affection for the sheer power of big businesses, but at the same time he believed that elected government must be sovereign over business.

In his earlier years, Roosevelt’s faith in law enforcement won the day, but in his later years he lost patience. When running for president in 1912 as the head of his own party, Roosevelt became the advocate of a different approach—one then new to American history, but with a difficult legacy in the twentieth century. Roosevelt campaigned on a platform he called “New Nationalism,” where he promised not to break up, but to nationalize or supervise the remaining trust monopolies. In other words, Roosevelt proposed abandoning the very idea of a competitive or decentralized economy, in favor of one dominated by monopolists who were then, in turn, subject to the direction and regulation of the state—the paradigm of “regulated monopoly.” Roosevelt’s approach, later termed “corporatism” by political scientists, was at some level not really so different from the Crown monopolies loyal to the British King, nor, as we discuss more in a moment, was it that much different than the corporate-state alliances adopted by Japan, Germany, and Italy in the 1930s.

There was more here than a rejection of antitrust: It was a rejection of the entire idea of a competitive economy, and that is what makes the 1912 election so important to our story. With Roosevelt and the socialist candidate Eugene Debs both calling for state-supervised monopolies, it became one of the few elections in history where the public was clearly engaged with and voting on what kind of economic order they wished to live in. On the one hand, here was candidate Roosevelt promising a future of monopolies supervised by an all-powerful federal government—as he said, “to give the National Government complete power over the organization and capitalization of all business concerns.” On the other, Taft, the Republican, and Wilson, the Democrat, both promised to restore a competitive economy by fighting the trusts with the antitrust law and new regulations—ironically, doubling down on the model Roosevelt himself pioneered. Debs, the socialist candidate, called the antitrust law “silly” and “puerile,” for he believed in an economy composed of monopolies controlled by the people. As he put it, “Monopoly is certain and sure. It is merely a question of whether we will be collectively owned monopolies, for the good of the race, or whether they will be privately owned for the power, pleasure, and glory of the Morgans, Rockefellers, Guggenheims, and Carnegies.”

It is interesting to speculate on how the history of the United States might have turned out had Roosevelt won. Perhaps it would have amounted in the end to little more than the selective nationalization of most of their public utility and telecommunications providers practiced by other Western democracies like Britain and France. But Roosevelt had promised to go further, to accept regulated monopolies across the entire economy, suggesting something similar to the extreme approaches taken by the Italian and German governments over the 1930s. What Roosevelt was proposing amounted to a union of political and economic power unknown even to the greatest of ancient emperors. All commerce would be controlled by a small group of monopolists, who would be, in turn, controlled by government (or perhaps vice versa). If Roosevelt had won the 1912 election, and managed to enact his program, the history of the United States would have been profoundly different, and probably far darker, given the fact that such cooperation was so closely linked to the rise of fascism in other countries. Unfortunately, the monopolist and dictator tend to have overlapping interests.

But Woodrow Wilson won the 1912 election, based on economic and antitrust policies directly taken from Louis Brandeis, his economic advisor—which the latter labeled “regulated competition.” The Roosevelt-Debs proposal of supervised monopolies was not popular: the competing candidates took some 65 percent of the popular vote.

After Wilson’s victory, Congress proceeded to fortify the antitrust laws with a series of new statutes. The Clayton Act of 1914 ratified and toughened the Sherman Act and explicitly criminalized particular anticompetitive practices. That same year, Congress created a specialized competition and consumer protection agency named the Federal Trade Commission and gave it powers to investigate and bring suit against any “unfair methods of competition.”* The importance of these new laws lies not just in their specific provisions, but in their democratic resolution of the uncertainty surrounding the purpose of the Sherman Act. The new laws were a Congressional ratification of the view that the antitrust laws were meant not to be merely symbolic, or just to benefit small producers or consumers. When we add up the popular vote for President and the subsequent passage of stronger antitrust laws in 1914 it becomes clear that the Wilson-Brandeis economic antitrust program enjoyed a powerful democratic validation—one arguably of Constitutional significance.†

In short, in the 1910s, it is fair to say that the United States made a choice. As Brandeis would later say, the nation had picked decentralization over concentration, and competition over monopoly. That choice has never been repealed, by democratic means anyhow.

*In subsequent years, the courts would strike down such laws as unconstitutional, in cases like Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905) (striking down a law setting maximum work hours) and Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 251 (1918) (holding a ban on child labor unconstitutional).

*We don’t have Morgan’s account of the meeting, and Roosevelt tended to tell stories in a manner so as to make himself look courageous, so the account given should be taken with a grain of salt.

*As a matter of legal method, Holmes’s reading is hard to support, and his opinion is in direct tension with his views, expressed in later opinions (like his Lochner dissent) that favored the majority’s right to decide economic policy, no matter what the judiciary might think. Perhaps he thought that the Sherman Act was only ever meant to be symbolic, the kind of strong but unenforceable statement legislatures occasionally make to placate the public. It is also the case that Holmes had himself become sympathetic to the idea that the trusts were an evolutionary improvement over “wasteful” competition. In a private letter he wrote that “there are great wastes in competition, due to advertisement, superfluous reduplication of establishments, etc. But those are the very things the trusts get rid of.”

*The idea of a simple line between the good and bad monopolist may seem too simplistic for such a vital question but it is also not necessarily easy to improve upon. If we leap forward to consider the tech monopolies of our times, we can see that the good/bad question is inescapable. More than a hundred years later, a version of Roosevelt’s line remains the centerpiece of the U.S. Supreme Court’s test for assessing whether monopolization violates the Sherman Act, albeit in much drier, lawyerly language. The test, from United States v. Grinnell, condemns “the willful acquisition or maintenance of [monopoly] power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.”

*Why would the railroads agree to the plan (which after all, lowered their prices)? Given the collective bargaining power of the major refineries, they may have given them little choice. But the deal also gave them guaranteed volume, and perhaps the opportunity to ward off their own competitors. In later years, Rockefeller would take substantial ownership interests in the railroads, which may have later played a factor.

*A longstanding revisionist history suggests that Standard Oil was a more efficient refiner that was unfairly condemned for having “lower prices.” Support comes from a 1958 study by economic historian John McGee, who concluded that Standard Oil had not, in fact, been proved to engage in below-cost pricing. (1 J. L. & Econ. 137.) Yet in fact Standard Oil relied on a menu of exclusionary tactics, not just predatory pricing, to gain and maintain monopoly. In 2012, Christopher Leslie reexamined the data relied upon by McGee, finding both distortions and also new data suggesting that the Standard did, indeed, price below cost. (85 S. Cal. L. Rev. 573.)

*If an oversized firm starts to suffer from the curse of bigness, why would a firm ever grow past its optimal size? This is not mysterious to any student of empire, or of human ambition; in contemporary economic theory it is usually described, as representing the difference between the interests of the corporation and its management. The owners of a corporation, the shareholders, may prefer a smaller profitable operation, but executives and founders prefer to run a great empire and conquer their rivals, an ambition that can easily overcome any effort to have a firm that operates at “efficient” size. As economist Michael Jensen, a founder of “agency theory” dryly explains: “Managers have incentives to cause their firms to grow beyond the optimal size” because “growth increases managers’ power by increasing the resources under their control.”

*The originally intended role of the Federal Trade Commission has always been slightly unclear. Historian Gerald Berk argues persuasively that Brandeis wanted the FTC to facilitate a middle ground between ruinous competition and monopolization—so-called “regulated competition.” See Gerald Berk, Louis D. Brandeis and the Making of Regulated Competition, 1900–1932 (2009).

†Based on the theory, popularized by Bruce Ackerman, that the Constitution undergoes de facto amendments during times of intense popular attention to questions of Constitutional significance. See Bruce A. Ackerman, We the People, Vol. 1: Foundations (1991).