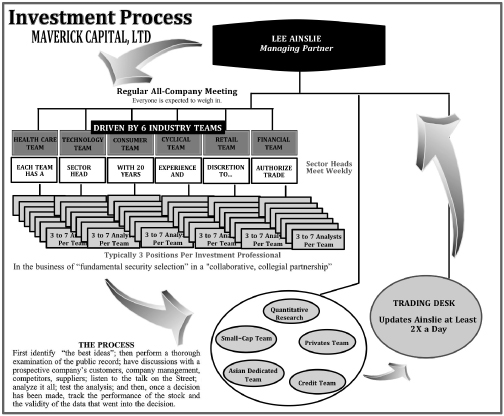

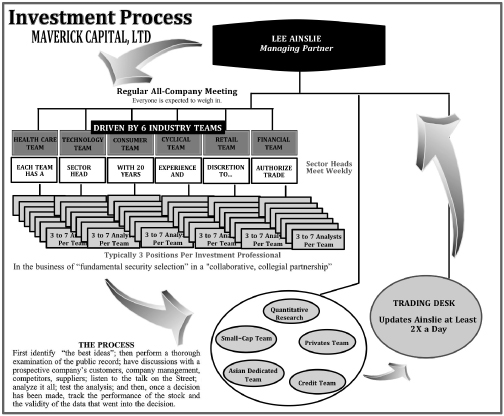

Figure 5.1 Maverick Capital’s Investment Process

Chapter 5

Digging Deep, Coming Up Big

Lee Ainslie

It is fitting that the big win Lee Ainslie is willing to talk about is a highly successful investment that his firm, Maverick Capital, made in a technology company. Technology is how Ainslie became interested in stocks in the first place.

He was 14.

An investment club had started up at his school, and the club members wanted to track a number of early computer stocks. It was the era of the Commodore PET, of Radio Shack’s TRS-80—known lovingly as the “Trash 80”—and of the legendary Apple II. Do-it-yourselfers, a large number of whom were schoolboys, were tireless in the creative uses to which they put BASIC, the Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code that was the first accessible language of computer programming. Young Lee Ainslie asked the teacher guiding the investment club if he could write a BASIC program that would track the stocks the club had interest in. The teacher said yes, and Ainslie wrote the program. He has been tracking stocks ever since.

He has also been investing in them with stunning success—first at the fabled Tiger Management Corporation, headed by his mentor, Julian Robertson, and then at the hedge fund he created in 1993, Maverick Capital, consistently recognized as one of the top funds in the world. Nevertheless, it was through being what Lee Ainslie describes as “a computer nerd,” that he discovered and embarked upon his life’s work.

The work is stock picking—pure and, if not simple, certainly classic. It is the classic purity of the process he applies and the sheer depth of the research he does that distinguish Ainslie and Maverick. Neither pure process nor depth of research is out of character for this soft-spoken southern gentleman with the analytic bent and competitive nature.

The school with the investment club and the early foray into computer programming was Virginia Episcopal School. Lee Ainslie went on to graduate from Episcopal High School, also in Virginia, a venerable institution known for its association with such historic figures as Walt Whitman, for its honor code, its religious focus, and for the rigor of the education it offers. He was not just a student there; he was part of the family. His father, Lee S. Ainslie Jr., for whom the school’s current arts center is named, became the headmaster shortly before Lee’s senior year. So it is probably safe to say that the things the school stands for—its serious educational purpose, high ethical standards, and meticulous discipline—quite naturally became part of young Lee’s extended DNA.

He took it all with him to the University of Virginia, where he concentrated on courses that fit his analytical bent, graduating with a BS in Systems Engineering. After college, he went to work for the head of information technology at KPMG Peat Marwick, exercising his penchant for technology. Perhaps being the son of a headmaster and understanding the value of education had something to do with it, or perhaps it was just an unquenched thirst for more knowledge, a trait that would be the hallmark of his investing style. But whatever the motivation, Ainslie left his consulting career and enrolled at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School in Chapel Hill.

Returning to the South was a fortuitous move for Ainslie, for it was there at UNC that he encountered Julian Robertson, at the time a member of the Board of Trustees of the university and, as it turned out, another Episcopal High School alumnus. Robertson attended UNC as an undergraduate and had been managing a portion of the university’s endowment for some time. Rightfully credited as one of the pioneers of the hedge fund industry, Robertson founded Tiger Management in 1980, overseeing investor assets of $8 million. By the late 1990s, Tiger’s assets under management would swell to $22 billion.1 Robertson must have taken note of the young guy with the familiar name, for when Ainslie had graduated and was “looking around for opportunities,” Robertson called and invited him to New York for an interview.

Still a young firm at that time, Tiger was seen by many on the Street as an unconventional—even aggressive—upstart, not the natural choice of an MBA grad looking for a career in finance. Ainslie, not to put too fine a point on it, could probably have had his pick of established financial institutions to join. “Go with a Goldman Sachs-type firm!” he was advised by more than one well-meaning confidant. “There is no better experience for your resume.” Ainslie listened, letting all the well-intentioned advice seep into his still-open mind. He flew to New York on a Wednesday, essentially interned at the Tiger offices on Thursday and Friday, and was offered a position the next week. His decision process was less tortuous than that of the people whose counsel he sought; in fact, for Ainslie, it was as simple as a college athlete deciding to go pro. “There wasn’t anything else I’d rather do. Somebody was going to pay me to do what I loved to do. It was no contest.” Thus, Lee Ainslie began his career as one of the early investment professionals of Tiger Management Corporation. He started hedge fund life as a generalist, but would eventually specialize in technology, his old standby.

For Ainslie, the time at Tiger was the equivalent of an apprenticeship. At first, he worked closely with consumer analyst Stephen Mandel, another Robertson protégé and the founder of hedge fund giant, Lone Pine Capital. By the end of his first year, however, Robertson asked Ainslie to focus on the technology sector. It was 1990, and not too many people were interested in tech companies or tech stocks. But Robertson apparently understood the investment potential of the technology industry, and he certainly sensed that Ainslie understood the role of technology itself.

It was exciting to take on this role at such a young age—Ainslie was 26—and at such an early point in what would undoubtedly be an enduring career. “The downside,” he says, “was having to develop expertise in a wide range of quickly changing companies, but the upside was that I had very few preconceived notions.” He was baptized into what he calls “the Tiger mentality.” It consisted of “finding the best business with the best management team and thinking in terms of years, not quarters. So you would end up picking a Cisco or a Microsoft, where most firms were more focused on which companies were going to beat the next quarter, which is a very tough way to add value consistently.” And, Ainslie might have added, probably not nearly as profitable or effective. Hedge funds are often mistakenly painted with a broad brush, as hair trigger traders seeking to make quick profits. But Tiger, Maverick—in fact, most hedge funds—are the antithesis of fast acting, preferring to take a very long term view. It is a cause and effect relationship with investments; the recognition that they have to be early to a story since that is when the opportunity is the greatest and the understanding that it will take patience for the fundamentals to unfold, the combination of which should result in strong performance.

Every stock pick had to go through Julian Robertson, and typically months of work preceded a presentation to him. “Julian was a quick study,” Ainslie recalls, “and halfway through, he could say, ‘Okay, buy it.’ But if he didn’t agree, he would let you know that too.” Persuading Robertson, however, was, as it should have been, a tough assignment that took all the intellectual rigor, analysis, breadth of scope, and presentation skills that Ainslie or anyone making a pitch could muster. There probably could not have been a better course of training in the business of selecting investments and building a portfolio than the work Lee Ainslie carried out at Tiger—the research, the questioning, the probing, the study, the re-examining, the putting it all together. It was a lifetime of learning compressed into three short, exhilarating years. (While at Salomon Brothers, I was responsible for the day-to-day relationship with Tiger and it was akin to dealing with a team of all-stars.) When, in 1993, Texas entrepreneur Sam Wyly approached Ainslie and asked him to run a money management fund he was seeding with $38 million of Wyly family money, Ainslie felt he had to listen. It was a chance to do prematurely what he knew he wanted to do at some point in his career—run his own firm. That fall Maverick Capital was launched. While Ainslie managed the stock portfolio, Wyly managed debt positions for the first 17 months. By early 1995, the firm had sold off all its non-equity positions, leaving Ainslie solely in charge of the portfolio. In 1997, he acquired a controlling interest in the firm.

Ainslie is aware that his pursuit of success at Maverick can become all-consuming. He admits to growing antsy as Sunday afternoon rolls around—“I want Japan to open so the game will be back on.” When you are running an operation that by definition ignores regional boundaries and time zones in seeking out the best investment opportunities, the clock offers little respite. With financial markets more widely dispersed than ever before across a truly global economy, there is always a market open somewhere, always a data point emerging that Ainslie and his colleagues don’t dare miss. While Maverick is not a trading firm, the drive to stay on top of information that affects the portfolio is in the partners’ blood. Garnering information before others is a critical edge in Maverick’s pursuit of generating high returns and preserving capital. All of this takes a significant amount of time. In order to guarantee that he is left with worthwhile time to spend with his family, he limits his civic and philanthropic activities almost exclusively to chairing the Board of Directors of the Robin Hood Foundation, a weighty responsibility that he takes very seriously as the foundation redefines the way donors and grant-makers target poverty in New York City. To further ensure quality time with his family, he built Maverick to perform using a teamwork model so that “it is not dependent on any one individual.” In turn, when he is at work, he is there 100 percent. His competitive self would have it no other way.

While others contribute to Maverick’s success, it is still the firm Lee S. Ainslie III created and built according to his own specifications. Right from the get-go, he knew just what kind of process and culture he wanted it to have.

First, he kept it simple. It was to be a classic equities-only fund, in which short positions were to be true investments, not just hedging mechanisms, balanced with long positions within each industry sector and in the context of a net long fund. Deep and exhaustive research was to provide the competitive edge, and a peer-group team-based culture was to make it all work. Perhaps building the culture was the most daunting task of running the business, not just because of the nature of hedge funds but of money management firms overall. Often, the biggest gains in a portfolio are generated by going against consensus and finding the idea that everyone else hates or chooses to ignore. This requires a certain independence, a willingness to stand up and profess love for a stock while a vocal majority casts aspersions on the investment case you are making. As the name suggests, Maverick reveres independence. It seeks to build, within a team framework, an opportunity for the oft-ignored loner voice to be heard and for independent thought to be considered. This approach has worked extremely well, averaging an annual return of 17 percent from the time Ainslie stepped away from Wyly up to the financial crisis of 2008. The years 2003 and 2005 were marked by underperformance and Ainslie took note of the reasons, learning some key lessons. In 2003, low interest rates had undermined the firm’s short positions—a lesson about the power of external macro forces. In 2005, the trouble wasn’t macro trends but a weakening of the team culture, according to Ainslie’s analysis. Sector teams had become isolated into separate silos and had grown unwilling to assume sufficient risk. It’s a flaw Ainslie has worked hard to correct. Then 2011 hit, another down year for Maverick, but one that proved extremely difficult for a number of otherwise top performing funds.

Maverick’s investment team started out consisting of a single professional—namely, Lee S. Ainslie III. Today, it consists of 55 investment professionals. See Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Maverick Capital’s Investment Process

The investment team is driven by six industry teams—healthcare, technology, consumer, cyclical, retail, and financial—which have global responsibility. Each sector head of these six teams is an expert in that industry—the current sector heads average nearly 20 years of experience in “their” industry—and represent an unparalleled resource of knowledge about the industry and of relationships with industry movers and shakers. In addition to these industry sector teams, Maverick has quantitative research, credit, small cap, privates, and Asian dedicated teams. All are in the business of “fundamental security selection.” As Ainslie neatly puts it, “Every business decision is based on how it impacts our ability to deliver returns to our investors.” Figure 5.1 tracks Maverick’s investment process.

Driving this simple model is what Ainslie describes as a “collaborative, collegial partnership.” He further expounds on the culture, “I’m a partner of the firm, and there are many important partners.” All are rewarded by “how we do as a firm, so there is an incentive to help one another.”

The structure reinforces this principle. While each sector head has discretion to authorize a trade, every investment team—comprising typically from three to seven analysts—meets weekly; all the sector heads meet regularly; and there is a regular all-company meeting as well. Ideas are aired, virtually from the moment they’re conceived, and everyone is encouraged—indeed, expected—to weigh in. The idea is to plant and sustain a holistic view, in which varied seeds of intelligence can be germinated and nurture one another.

Ainslie is in touch with the sector heads throughout the day, sits in on most meetings, and gets an update twice a day or more from the trading desk, which he regards as the firm’s “eyes and ears on the market.” Industry sector professionals glued to a computer screen is, he says, “the last thing I want to see.” After all, Maverick is not in the business of responding to market movements but rather to bottom-up fundamental data points. Whether the market is up or down one, two, or three percent is immaterial to the Maverick investment thesis on its individual holdings; it is only noise. But investment firms cannot operate in a vacuum, and the trading desk is the firm’s finger on the pulse of the market—and on world events that may affect the markets. Leaving the news updates to the trading desk both frees the investment professionals to concentrate on the long term and gives Ainslie a direct and up-to-the-nanosecond line on what’s happening in the wider world. At day’s end, the Maverick team sifts through company, industry, and macro updates and evaluates each position in terms of whether or not it is as good a use of Maverick’s capital today as it was yesterday. They try to identify what he describes as “the best ideas” about where Maverick should be investing in an effort to decide how much capital should go where. As Ainslie learned from Julian Robertson, the test of a decision is buy versus sell; there is no hold option. The choice is made every day, either by default or by volition. The meaning is clear: Every day the equities markets are open for trading your portfolio is alive, and by holding onto a position you are very much making the statement that you would buy it again that day.

Feeding this daily decision making is a body of exhaustive research, considered by the market—and by Ainslie—as a prime competitive advantage of Maverick Capital. As he famously told two McKinsey interviewers in 2006, “Our goal is to know more about every one of the companies in which we invest than any non-insider does.”2 It’s a good bet Maverick meets that goal.

The research is gathered via a method that typically takes a few months before an initial purchase and could then require many months to build a full position. The professional staff performs a thorough examination of the public record, has discussions with a prospective portfolio company’s customers, discussions with its management, discussions with competitors, discussions with suppliers, and listens to the talk on the Street, analyzing it all, testing the analysis, and then, once a decision has been made, tracking the performance not just of the stock but of the validity and effective use of the data that went into the decision. Apart from everything else, tracking exactly how each decision worked out in terms of cold, hard performance is a way to continually refresh and improve the Maverick process and its culture. The process may be said to start with the fact that the number of investment positions per investment professional is typically about three—a distinctive depth of diligence right there, enabling a very high concentration of research. The point of this is that in order to take a position, it has to be concluded that the new holding is the best use of the firm’s capital, and in concert with the requirement to know more than anyone else about what the firm owns, the number of holdings per capita could be said to be limited by Maverick’s process.

“We’re a team of peers,” Ainslie asserts. “There is no king of the hill.” It makes for a distinctive environment, and as Ainslie concedes, “There are many talented people who do not enjoy such a team-oriented environment.” Those who do, however, rarely want to leave; at the senior level, turnover has been negligible. To build depth of bench, however, the firm recruits a pool of candidates from among “second-year” performers at the top investment banks, consulting shops, and corporations. A winnowing process narrows the number of applicants in the pool, and these candidates are then interviewed and tested. After reviewing the results of rounds of interviewing and testing, a select number of finalists are invited to take part in a final day of interviewing, which typically starts at 7:00 in the morning. The applicant is given a computer and presented with a case study to evaluate and about which to offer a conclusion. “We see what they can do with it,” Ainslie states. The applicant goes on to a series of interviews with the senior partners, each conversation probing the candidate on “a different component of success at Maverick,” components that have been identified as key to the work—logic, rationality, emotional consistency, the ability to cope with stress, among others. In return for this fairly grueling process, new hires get a two-year commitment plus training.

Not surprisingly, Maverick has kept data on which hires were recommended by which senior partners, so that “Years later,” Ainslie says, “we can see who was right.” It is,” Ainslie repeats, a matter of “improving the process.”

It’s safe to say that in the year 2000, when then-CEO of General Electric, Jack Welch, spoke, people paid attention. Some of the tech analysts who would wind up at Maverick listened attentively when Welch proclaimed his 70-70-70 rule for GE: 70 percent of technology processes to be outsourced; 70 percent of that 70 to go overseas; and 70 percent of the overseas 70 to go to India. By 2002, the Maverick tech team, under the leadership of Andrew Warford, started looking at one of the original Indian information technology outsourcees, Cognizant.

The selling points were obvious: Claims that outsourcing could save one third of the cost of business processes were common, and in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with the economy stumbling, businesses were desperate to reduce costs. Conventional wisdom, however, held that the desperation was overblown, had run its course, and would soon be on the wane as the economy in general improved. The Maverick technology team thought otherwise. They posited the thesis that the cost-cutting outsourcing experiment had seen such strong results in terms of savings, with work that was equal in quality to, if not better than, what could be produced in-house, that customers would actually do more outsourcing, not less. In fact, Warford and the team believed that the initial, tentative, somewhat tepid flight to outsourcing was actually the start of a long-term trend, and that Cognizant represented a technology-enabled business that could be instantly exported and that would grow accordingly.

Then they set out to test the thesis.

Step one was to talk to customers. How is that done? It’s a bit like detective work: You make a call, get a lead, follow it, get another lead, and keep on digging. In the case of Cognizant, Maverick’s researchers talked to customers that represented more than half of their revenues, interviewing chief information officers all over the world. What they learned was stunning: Virtually every customer they talked to said they planned to expand their business with Cognizant in the succeeding year. “That increment alone,” Ainslie reports, “was the growth Wall Street expected for the whole company”—without Cognizant adding a single new customer. Says Ainslie: “We had never seen anything that powerful.”

Step two of testing the thesis was to talk to competitors—mainly Infosys and Wipro—and managers at both painted a picture of stable pricing and heavy demand for their services, in contrast to the common Wall Street concern of margin pressures on the business. In any event, the research found that Cognizant’s operating margin in the low 20s was significantly lower than its competition. This created a margin of safety relative to competitors that established greater earnings stability and allowed room for incremental investments versus the competition.

Step three was to kick the tires of management. In trips to India, as well as in meetings with Cognizant management in their U.S. offices, the tech team reviewed the financials and discussed the company’s strategies for maximizing shareholder value and for dealing with potential pressures on margin.

Finally, in step four, the Warford led team talked with suppliers—specifically, with outplacement firms and universities—for a view of what employees entering that job market needed and could look forward to.

The research confirmed their thesis that Cognizant was positioned for growth in an industry about to take off and, in January 2003, Maverick built a substantial position in Cognizant stock, buying at a price of slightly less than $5 per share.3

Positioning the shares in the portfolio never marks the end of Maverick’s analytical process. In fact, says Ainslie, “The due diligence was ongoing for the full four-and-a-half years that we owned the stock.” Such ongoing research, essential at any time, is particularly important in the case of a new business, which Cognizant was, in a new industry, which outsourcing was, in order to keep on top of threats and opportunities. And even though the research can become more efficient over time, it is, says Ainslie, “like mowing the biggest lawn in the world”—just as you finish up, the grass has already grown too long again back at the beginning, and you have to start all over.

Besides, as noted earlier, there is always a data point popping up somewhere. Maintaining acuity on a non-U.S. stock presents a particular challenge; it is not just the company one has to stay on top of, but also local government laws, changing regulations, and the region’s operating environment. Some of these changes may be meaningful, so it is critical to know about them when they first bubble up, before the investment case is impaired. Without a local presence and boots on the ground, Maverick had to work that much harder to stay informed, and given the size of the fund’s position, staying informed was critical.

Principally because Cognizant was a company based in India, the stock price was volatile, but with the long-term view that Maverick’s depth of research and stability of assets made possible, that was understood and accepted. Peaks and valleys were within the realm of the position’s risk/reward profile.

The time came, however, when the position was no longer as good a use of Maverick’s capital as it had been the day before. There were two basic reasons for this. First, Cognizant’s growth had begun to slow somewhat, a natural and expected occurrence, and second, other investors had caught up to Maverick’s once non-consensus view on the future of outsourcing. At the intersection of those realities, maintaining the position no longer represented the best investment relative to other opportunities. In the investment business, as elsewhere, good things usually come to an end, so in July 2007, Maverick sold Cognizant, having realized an eightfold return worth “several hundred million dollars” in profit—a big win by any measure.

There is a postscript: As of this writing in 2011, Cognizant, priced at some 15 times what Maverick first paid for it, is back on the Maverick radar screen and back in its portfolio.

Maverick’s investment in Cognizant generated such a high return because there were fewer funds able and willing to buy the stock with the confidence such an investment required. This paucity of buyers created an inefficiency in the Cognizant stock price versus the value that could be realized if the investment case played out as Maverick’s analysis had forecast it would. At the foundation of the firm’s success on this stock, as with so many of its successes, was Maverick’s tried and true research process based upon the vast experience its analysts possess in emerging markets and their expertise in forensic analysis.

*This is discussed in greater detail in the accompanying sidebar. The filing requirements set forth by the SEC are, in part, dependent upon the exchange where the shares are traded; NASDAQ and NYSE have greater requirements than a Pink Sheets listing.

*I would actually argue that Cognizant is not a pure emerging markets growth story, given their customer base; at some point the calculation on valuation is a comparison to American companies with some discount applied given their foreign domicile.

†For illustration purposes only: This is not a suggestion or recommendation to buy shares in NII Holdings.

*EBITDA = Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization. EBITDA is a proxy for operating cash flow. EBIT, Earnings Before Interest and Taxes, is another valuation metric and proxy for cash flow preferred by certain investors. Both are discussed in Chapter 6 on Chuck Royce.

*In place in each country where NII Holdings does business is an indigenous management structure, including a President of Operations. This is particularly important in certain countries where the business and legislative communities are close knit.

*Companies trade on the Pink Sheets because they are either too small to meet the minimum requirements for listing on a national exchange or they do not want to provide the financial disclosure required by the SEC. So named because the listings were originally published on pink sheets of paper, these securities are more prone to manipulation and are often “penny” stocks—small market caps and often priced below a dollar per share.

†Exchange Act Rule 12g3-2(b). This rule provides an exemption to certain filing requirements for foreign private issuers in order to “remove needless barriers” to U.S. capital markets. This amendment to the original rule provided for the electronic transmission of certain filings, making the information more accessible to the average investor.

Notes

1. Putting this in perspective, a hedge fund at the time was considered extremely successful if it had $1 billion under management. Now, of course, the extreme success of those early days is a paltry sum that barely throws off a living wage for most hedge fund managers. In fact, there are a few who take home a billion in wages each year.

2. Richard Dobbs and Timothy Koller, “Inside a Hedge Fund: An Interview with the Managing Partner of Maverick Capital,” McKinsey on Finance, no. 19 (Spring 2006): 6–11.

3. Maverick does not concentrate its portfolio. It keeps positions to less than 5 percent of the firm’s equity.