Chapter 10

“MILLION WOMEN ARE NEEDED FOR WAR”

January–February 1942

T he coming of war prompted many and far-reaching changes in the United States. Presidential powers were immediately strengthened. Production was organized under a War Production Board that cut back on all civilian production, but particularly the manufacture of tires and automobiles. Civil defense measures were slowly introduced; a blackout (or “dimout” as it came to be called) was enforced, though not soon enough to prevent German submarines from cruising off the Eastern Seaboard at night to torpedo merchantmen sailing against the lit-up coast in full silhouette. The Times’s own electric bulletin was a victim of the lighting restrictions and Times Square was sunk in unaccustomed gloom. From a situation of high unemployment, the war economy now needed all the labor it could get. In late January the labor director of the War Production Board, Stanley Hillman, called for a million women to join the war industry. “Women can build airplanes,” he said, and millions of American women responded to the call over the three years that followed.

The black community lobbied to be allowed to join the war effort, prompting the formation in January of the first all-black Army division, though prejudice did not disappear. The American Red Cross refused to use the blood of black Americans for transfusions until pressured to do so by the government.

Roosevelt was feeling his way for the first weeks of war. In February The Times complained in its editorial, “Washington Paints a Confused Picture,” that the people had not yet been told the whole truth about the war crisis. The truth was bad enough. On February 15, the day the Japanese captured Singapore and more than 100,000 Allied prisoners, The Times’s military correspondent, Hanson Baldwin, warned that worse was to come from the “fanatical little fighters” of Japan. The early weeks of war were, he continued, “perhaps the blackest period in our history.” On January 2 the capital of the Philippines, Manila, fell to the Japanese Army and American and Filipino forces were pushed back onto the Bataan Peninsula and eventually into the fortress of Corregidor. Japanese troops swept all before them, capturing the Dutch East Indies in a lightning campaign and smashing an Allied naval force on February 27 in the Battle of the Java Sea. On February 22 General MacArthur was advised to leave the Philippines and to go to Australia. Earlier that month the popular Times journalist Byron (Barney) Darnton was sent to Australia to report on the Pacific crisis, only to lose his life nine months later when an Allied aircraft mistakenly attacked the landing craft Darnton was in on the way to the coast of New Guinea.

There was little news that was good. Benghazi in Libya fell to Rommel’s Afrika Korps; submarine sinkings reached new heights. The one ray of hope lay on the Eastern Front where the German armies were stuck in the snow and bitter weather, though far from defeated. Ilya Ehrenburg, the famous Soviet war correspondent, wrote for The Times from the front line where General Zhukov, Stalin’s military troubleshooter, claimed that the Germans had at last tasted “real war,” having grown too “used to easy victories.” The Times reported how well-equipped Soviet soldiers were, with their high felt boots (valenki) and sheepskin jackets, while the German Army was forced to appeal to countrymen back home to send their fur coats and sweaters to clothe German soldiers. Although the Pacific took pride of place in news reports, Roosevelt was clear when he met Churchill in Washington for the Arcadia conference in December 1941 that the priority was to destroy the German threat. On January 26 the first units of an American Expeditionary Force landed in Northern Ireland, the early contingents of what was to become the largest overseas army ever raised by the United States.

WAR PACT IS SIGNED U.S., Britain, Russia, China and 22 Others Join in Declaration

By FRANK L. KLUCKHOHN

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, Jan. 2 —All twenty-six countries at war with one or more of the Axis powers have pledged themselves in a “Declaration by United Nations” not to make a separate armistice or peace and to employ full military or economic resources against the enemy each is fighting. The agreement was signed in Washington and made public today at the White House.

The declaration, which is an outcome of the recent conferences between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill of Great Britain, is not in treaty form, and therefore does not require ratification.

President Roosevelt signed for the United States; Prime Minister Churchill for the United Kingdom; Maxim M. Litvinoff, the Soviet Ambassador, for Russia, and T. V. Soong, Foreign Minister, for China. Representatives here affixed their signatures on behalf of the Dominion and India governments and for the exiled and Central American governments. The Free French did not sign and neither did any South American government, but other nations “rendering material assistance” may adhere for “victory over Hitlerism.”

ALL IN ‘A COMMON STRUGGLE’

The declaration, carefully phrased to make it unnecessary for Russia to go to war against Japan, was made public at 3 P.M., only a few hours after announcement that Japanese forces had occupied Manila.

The adherents expressed conviction that “complete victory over their enemies” is essential for defense of “life, liberty, independence and religious freedom,” not only in their own but in other lands. Each declared itself engaged in “a common struggle” against evil forces seeking world dominance.

Therefore each signatory, on behalf of his government, pledged cooperation with the other governments involved and “not to make a separate armistice or peace with the enemies.” Some Latin-American nations at war have small armies, which may explain why each government pledged employment of full military “or” economic resources “against those members of the Tripartite Pact and its adherents with which such government is at war.”

The declaration was on a common war policy, but it pledged all nations involved to accept, after “final destruction of the Nazi tyranny,” the eight bases for establishment of peace contained in the Atlantic Charter signed by President Roosevelt and Mr. Churchill at their sea conference on Aug. 14, 1941.

JANUARY 4, 1942

Editorial

CIVIL LIBERTIES IN WAR

“Total war” is a crucial test of our ordinary theories and practices of government and of the democratic and libertarian principles by which we strive to live. The fearful exigencies of war force us to re-examine many of our political premises. Among those are the premises concerning our civil liberties. One set of extremists is apt to take the position that all civil liberties have to be suspended during the period of the war. Those at the opposite extreme are apt to contend that there should be no abridgment whatever of any peacetime civil liberty.

Obviously the truth is somewhere between these extremes. But to find precisely where it lies in particular cases is not easy. Dr. Stuart A. Queen, retiring president of the American Sociological Society, in an address posed a few questions designed to show the nature of the dilemmas which the present war raises: “Shall freedom of communication,” he asks, “be maintained for all, thus aiding enemies in our midst, or shall it be restricted, thus threatening the very democracy for which we fight?” Such a question may overstate the problem, but it does serve to emphasize the truth of Dr. Queen’s conclusion that civil liberty is “one of the most difficult problems for a democratic people in time of emergency.”

In normal times we are apt to say that the various civil liberties we enjoy are “absolute” and “inalienable rights.” Yet our actual practice has never corresponded with these phrases. It would be difficult to name a civil liberty that has not in practice been subject to some qualification. Thus the right of free speech has never been absolute. It has been curbed by the laws against libel, against obscenity, against direct incitement to riot or violence. Different ages and different communities have varied widely in where they draw the line in all these cases, but it is extremely seldom that they have failed to draw a line at all. In war-time these qualifications are necessarily greater. The press is not allowed to print military secrets. Individuals are not allowed to make treasonable utterances, and the definition of what is likely to cause internal dissension is in practice greatly broadened.

Liberty should never be conceived in a purely negative sense, as the mere absence of restraint. Such a conception would lead only to anarchy. To determine what are desirable liberties, we must refer to some end beyond mere absence of restraint itself. This end is the national welfare, considered in the broadest sense. Obviously the national security demands more qualifications to individual liberty in wartime than in peacetime. But all this does not mean that individual liberties should be reduced to such a point that the future of liberal and democratic institutions is endangered. It does not mean that any one Government authority or small group is to have unrestricted power to dictate what liberties are to be abridged. It does not mean that individuals are to be restricted in their right freely to criticize the Government’s diplomatic policies or its conduct of the war. Long established legal safeguards designed to protect individual rights are not lightly to be put aside.

We cannot surrender at home the very liberties and democratic principles for which we are fighting. But we must recognize that in particular cases decisions concerning the qualifications to civil liberties will often be much more difficult to make now than in times of peace.

DETROIT RESIGNED TO AUTO-BAN EDICT

Gradual Slashing of Production Schedules Had Prepared Area for Shift to Arming

By FRANK B. WOODFORD

DETROIT, Jan. 3 —The virtual wiping out of Detroit’s chief industry through Federal Price Administrator Leon Henderson’s order banning the production of new passenger cars and trucks has been accepted here with resignation which is tinged, in some quarters, with resentment.

For several months now the automobile industry has watched its production schedules being slashed. Throughout most of the industry it was accepted as inevitable that some such order as Mr. Henderson’s would eventually come through. Particularly has this been the feeling since the entry of the United States into the war with the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7.

HOPED-FOR DELAY

But while it was preparing to accept the inevitable, Detroit and that part of the industry which is located in and adjacent to the city had hoped that the total end to the sale and production of civilian cars would be delayed until the automobile factories could reabsorb their entire employment and shift their manufacturing facilities to war production.

The immediate effect of Mr. Henderson’s order stopping all production on or about Feb. 1 will be large and accelerated lay-offs which will bring almost total unemployment to about 250,000 persons in this area.

This, in turn, creates other problems. Governmental agencies have already begun a frantic search for revenues to carry the welfare loads and to handle the demand for unemployment compensation. War employment in the factories where the automobiles have been produced is gaining steadily, but it will be months before all the unemployment slack can be taken up in the production of war materials.

THE JOBLESS WORKER

To the jobless worker now or about to be on the streets there is small comfort in the statement at this time from some of the industry heads that a few months will not only find them all back at work but will see an acute labor shortage in the automobile plants at the same time.

The new order has been accepted cheerfully and willingly by the industry. Alvan Macauley, chairman of the Packard Motor Car Company and president of the Automobile Manufacturers Association, spoke for the industry when he pledged its complete cooperation under the edict of the Office of Production Management which ended the manufacture of automobiles and trucks.

“If that’s what the government wants, we’re going to be with it all the way,” Mr. Macauley said concerning the stop-production order.

“But manufacturers must have more defense contracts which they can put into production on a mass scale,” he added.

On the other hand, the United Automobile Workers (C.I.O.), while accepting the situation with patriotic good grace, criticized the fact that adjustment had not been made earlier in order to avert the mass layoffs which will come with the changeover from peace to war production.

THOMAS’S STATEMENT

“The automobile workers are ready to endure any hardship which will contribute to the victory of our nation,” said R. J. Thomas, president of the union. “However, we can’t see the sense in blacking out the country’s greatest reservoir of machinery and trained labor.

“Most of the automobile industry machinery can be converted to production of armaments. We proposed that a year ago. We did not get far. Now that the industry knows it cannot make cars any longer, it is freely granting that its facilities can be changed over to make the materials of modern warfare.

“The most important single task before the nation is the rapid conversion of the automobile industry to war production. It can and should be made the major production arm of the arsenal of democracy. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of unemployed automobile workers must have their needs and those of their families taken care of by adequate unemployment compensation allowances and WPA appropriations.”

The factory floor of a former Chrysler automobile assembly plant after its wartime conversion to manufacturing tanks for the military, Detroit, 1942.

One very real fear, affecting both management and labor, is what effect the possible shortage of private cars, coupled with the strict rationing of tires, will have on needed transportation in connection with war production in this area. A large part of the production facilities, notably the Chrysler tank arsenal, the Hudson arsenal and the Ford bomber plant, are on the outskirts of the city, unserved by existing bus or street car facilities.

Private transportation is relied on in each instance to get the men to and from work.

Although dealers report an adequate stock of used cars in this area, there has been the expression of belief that these may be commandeered to relieve shortages in other sections of the country, leaving Detroit with a serious new and used car shortage.

The Willow Run bomber plant of the Ford Motor Company is located nearly twenty miles from Detroit. By early Summer the company contemplates employing 60,000 workers there. Nearly all of these will be drawn from Detroit and will be forced to use private transportation. Not only are there no present bus lines to the plant, but transportation officials here doubt that there will be sufficient equipment available to establish new lines.

JANUARY 12, 1942

NAZIS LIST CLOTHING GIFTS

BERLIN, Jan. 11 (From German broadcast recorded by The United Press in New York) —D.N.B., official news agency, reported today that in the sixteen-day collection of clothing for German soldiers 56,325,930 items had been donated.

The donations included 2,958,155 fur garments, 4,948,766 sweaters and other wool clothing, 7,781,711 pairs of hose, 104,841 pairs of fur-lined boots, 170,214 pairs of plain boots, 1,174,748 pairs of skis, 3,138,405 wool hoods, 3,854,064 pairs of gloves and 1,485,115 wool and fur blankets.

The Prague radio was quoted by the London radio in a broadcast heard by the Columbia Broadcasting System as announcing that today was the forty-ninth birthday of Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering and that “the people of Czecho-Slovakia are expected to celebrate the occasion by contributing old clothes to the national rag bag now being assembled for troops on the Russian front.”

JANUARY 13, 1942

WAR INCREASES BICYCLE’S POPULARITY AMONG WOMEN

Speculation on the influence on transportation of the recent tire rationing order has brought the bicycle industry into the forefront of discussion, especially among housewives in suburban areas, many of whom took up cycling some time ago. Investigation indicates that travel to market by bicycle will increase rather than diminish.

Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt is among those who have acquired bicycles in the last few months. Her activities at Civilian Defense headquarters in Washington, however, have prevented her usual visits to Hyde Park, where the bicycle awaits her leisure. She has not yet had time to learn to ride.

Although production of bicycle tires will remain under curtailment, those al ready manufactured may be sold. Additional reassurance may be forthcoming in the expected final approval of the industry’s scheduled program of production for 1942. A clearance signal is now awaited on the general lines of a tentative program drawn up at a meeting late in December of industry representatives and officials of the OPM. The plan calls for the manufacture of 1,000,000 bicycles this year, stipulating that a universal, simplified design of light-weight will be used.

The return of the bicycle as a means of recreation has not yet given rise to a definite trend in feminine sports wear. Unlike the Gibson Girl bicyclists of another day, today’s women riders have been content with makeshift ensembles, often unsuitable. The most practical and becoming outfit yet evolved is the jupe-culotte, worn with a pullover, and a leather jacket or wind-breaker. A hood that ties securely under the chin, fleece-lined mittens and sturdy shoes complete a well-planned cycling costume for current months.

Two-wheeled transport in upstate New York, 1942.

JANUARY 13, 1942

THE NAVY IN TWO SEAS

One answer to the question of what the American Navy is doing in this war was given yesterday by Secretary Knox in a speech prepared for delivery at the annual Conference of Mayors in Washington. The Navy is achieving notable success in keeping open the most important highway in the world—the sea-lanes between the United States and the British Islands. It is because so large a force is engaged in this essential task that Mr. Knox warned his audience not to expect “full-scale naval engagements in the Pacific in the near future.” He asked for popular understanding and approval of the strategy that keeps so large a part of the Navy occupied in the Atlantic: “We know who our great enemy is—the enemy who, before all others, must be defeated first. It is not Japan; it is not Italy; it is Hitler and Hitler’s Nazis, Hitler’s Germany.”

Fortunately Mr. Knox does not need to argue his point. The country accepted it from the moment we went to war. It is proof of the level-headedness of the American people that even in the first days after the infuriating attack at Pearl Harbor—in the days before Mr. Churchill came to this country and before the importance of the front against Hitler was emphasized by the organization of the grand alliance of twenty-six United Nations—the American public never lost sight of the real objective. On this point the evidence of the Gallup survey is convincing. During the period of Dec. 11–19, a period beginning immediately after Pearl Harbor, Dr. Gallup’s organization found that more than four times as many Americans regard Germany as a greater threat than Japan. Moreover, there was no sectional disagreement on this fundamental point. The opinion of the Far West coincided almost exactly with the opinion of the rest of the country.

The average American knows that a victory over Japan would bring us no security whatever so long as Hitler remained unconquered, whereas the defeat of Hitler would enormously hasten, if it did not almost automatically accomplish, the defeat of his Eastern ally. But to beat Hitler we need production and still more production, and the sacrifice of every group interest to the national purpose.

ROOSEVELT SIGNS DAYLIGHT TIME ACT

Clocks Are to Be Moved Ahead by One Hour At 2 o’Clock on Morning of Feb. 9

LARGE SAVING OF POWER

By The Associated Press.

WASHINGTON, Jan. 20 —President Roosevelt signed the Daylight-Saving Bill today and it becomes effective at 2 o’clock in the morning of Feb. 9 for all interstate commerce and Federal Government activities.

During Congressional debate it was assumed that the new time, by which clocks are moved ahead one hour, would become general throughout the country.

The measure will become inoperative six months after the war ends, unless Congress votes to terminate it before then.

Stephen Early, Presidential secretary, said that the measure had the same objectives as the Daylight-Saving Act of the first World War, that is, “greater efficiency in our industrial war effort.”

The Federal Power Commission estimated there would be a saving of 736,282,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity annually. It said the nation used 144,984,565,000 kilowatt-hours in 1940. The real benefit from the change, the F.P.C. said, would come from relieving the present peak demand for power between dark and bedtime. The commission estimated that the change would provide relief to the extent of 741,160 kilowatts of production capacity.

Congressional action was necessary, Mr. Early pointed out, so that there would be a uniform system in all the States.

President Roosevelt directed that the pen which he used in signing the bill should be sent to Robert Garland of Pittsburgh, who headed a national committee that appeared at hearings on the legislation and urged its enactment.

Mr. Early said Mr. Garland also was active in advocating daylight saving for the first World War and had asked for no greater return than the pen used by President Woodrow Wilson in signing the act at that time.

JANUARY 22, 1942

Foe Hurled Back in Bataan; Guerrillas Kill 110 at Base

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, Jan 21 —The small force holding the Bataan Peninsula on Luzon Island, in the Philippines, scored a new victory in “savage” fighting by throwing back with heavy losses Japanese attackers who had penetrated their lines, the War Department announced today. In addition to taking the initiative and sustaining it with “relatively moderate” losses to the United States–Philippine Army, General Douglas MacArthur reported to the War Department that one of the guerrilla bands cooperating with the defending army raided a hostile airdrome at Tuguegarao to the north, killed 110 Japanese and routed 300 others.

ENDS DRAMATIC CHAPTER

Today’s communiqué on fighting in the Philippines closed a chapter of operations made more dramatic by the fact that the communiqué of yesterday was issued while the end of the battle was a matter of grave doubt.

For two days the augmented Japanese forces, supported by air bombers and strafing planes, had lunged at the center of the fifteen-mile line across the neck of the Bataan peninsula in an effort to force a break in the lines and open up the hilly country to raiding.

“In particularly savage fighting,” the communiqué today said, “on the Bataan peninsula, American and Philippine troops drove back the enemy and re-established lines which previously had been penetrated. The Japanese, by infiltrations and frontal attacks near the center of the lines, had gained some initial successes. Our troops then counter-attacked and all positions were retaken. Enemy losses were very heavy. Our casualties were relatively moderate.”

To military observers here, this report indicated a picture of fighting by which General MacArthur adapted frontier methods to his defense against an army which is overwhelming in size and which apparently has attempted to adapt German blitz methods to its campaign in mountains and swamps.

When the Japanese have advanced, with tanks crashing through ground defenses and airplanes raining explosives from the sky, the MacArthur lines apparently have dissolved into nothing, while the defenders have fallen back into shelters prepared for this eventuality. Then, when the attack has spent itself, they fall on the advancing units in groups, catching them completely disorganized.

These tactics have been indicated repeatedly by statements that the defending line is hardly a “line” at all but rather a series of prepared positions. In the heart of the small Bataan peninsula itself, the defenders have prepared countless positions carved out of stone mountains, which serve as bombproof shelters in air attacks and in which they have cached sufficient supplies to give them a long period of waiting.

The guerrilla raid, the communiqué reported, occurred in the Cagayan Valley in Northern Luzon, which is far removed from the scene of the principal fighting. The mere fact that it occurred gave increasing evidence that the Filipinos had not been completely defeated by any means. Only yesterday, another report told how another band 500 miles southward on the island of Mindanao was engaging Japanese forces that hold the port of Davao.

The guerrillas in Northern Luzon were said to have taken the Japanese “completely by surprise” and to have “scored a brilliant local success.”

JANUARY 23, 1942

ALL-NEGRO DIVISION FORMING FOR ARMY

MANY IN OFFICER COURSES

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, Jan. 22 —A Sixth Armored Division will be added to the Army’s battle force of tank troops Feb. 15, Secretary Stimson said today at a press conference in which he described plans for expediting the work of expanding the Army this year to a force of 3,600,000 men.

The Secretary said that four-week training programs in special operations would be given to all officers to be assigned to the thirty-two new “triangular” divisions and a new Negro division and a second Negro aviation squadron would be set up.

The Army expects to have its new Negro division in final shape by May, on station at Fort Huachuca, Ariz. This division, a triangular one, will be built up around various Negro units already in existence.

The squadron, to be known as the 100th Pursuit Squadron, will be trained at Tuskegee, Ala., site of the Negro institute, where the first organized Negro pursuit squadron, known as the Ninety-ninth, is completing its training.

NEGROES TRAINING TO BE OFFICERS

Coincident with this announcement of new Negro organizations, Secretary Stimson stated that Negroes were attending officer candidate schools for men selected from among draftees. In addition he noted that the main parade ground at Fort Knox recently was named Brooks Field, in honor of Private Robert H. Brooks, a Negro who was the first casualty in the armored force in the Philippines.

The new armored division will undertake training at a time when part of the armored force has already matured in training and achieved the goal of 100 per cent equipment, fitting it for duty anywhere in the world, Secretary Stimson said. Some units are less than fully equipped, but he asserted that they had sufficient arms for thorough training of the officers and men.

Members of the first class of black pilots in the history of the U.S. Army Air Corps who were graduated at the advanced flying school at Tuskeegee, Ala., as second lieutenants by Major General George E. Stratemeyer.

Each armored division consists of more than 10,000 officers and men, is composed of two tank regiments, three separate field artillery battalions, an infantry regiment, a reconnaissance battalion, an anti-tank battalion of motorized artillery, an engineer battalion, observation aircraft and the usual units to provide for the men and service the vehicles.

DIVISIONS ARE MINIATURE ARMIES

Each division, therefore, is a miniature army of extraordinary striking force, so composed that it may be divided into two or more independent arms. The new division, like those already formed, will be trained at Fort Knox, Ky.

The new training programs for officers are designed to send these men into their new commands completely equipped to teach their units the specialties of modern warfare required of each type of fighting unit. The first group to take the course will include 500 officers assigned to the three new triangular divisions to be formed within the next few weeks in the start toward a goal of thirty-two new divisions.

RUSSIAN UNIFORMS KEEP OUT THE COLD

High Boot of Felt Is Regarded as Important Factor In Red Army’s Winter Gains

Special Cable to The New York Times.

MOSCOW, Jan. 25 —The battle dress that is serving the Russian Army so well this winter provides a maximum of warmth with a minimum of handicap to freedom of movement.

Most important from the viewpoint of warmth are the Russians’ knee-high boots of thick felt—“valenki”—which many foreign military observers regard as a prime factor in the present Russian victories. These boots, which appear to be clumsy and shapeless, are made of a single piece of quarter-inch-thick felt and nothing more. One weighs about a pound and a half. Soldiers wear no socks beneath the boots, but bind their feet in cloth. The valenki give excellent protection when soldiers are standing or sitting. The snow is dry during most of the Winter, so the boots do not get wet.

Soldiers on the move sling their felt boots around their neck and wear high boots that are slightly higher in front than in back and are relatively light, weighing a little more than a pound apiece. They are very broad in the toe and give the Russian soldier on the march a somewhat ungainly pace, but they undoubtedly are highly practical. Many men wear an extra sole inside the leather boots, which are called “sapogi.”

Red Army breeches are of quilted kapok or padded with down, and they vary in weight according to the passing. They keep warm the vital part of the leg just above the knee, which, if chilled, seems to affect the whole body. Underneath the breeches are worn coarse trousers of no particular standard quality or weight.

Over his vest and tunic the Red Army man wears a sheepskin jacket—“shuba.” The jacket used in action is about knee length, but longer ones are issued for other activities. The jacket, with the wool inside, weighs about nine pounds and is a comfortable garment. It is rather tight at the waist, but loose in the shoulders.

The Red Army fur hat varies in weight, the average being twenty ounces, but the design is standard. The hat is basin-shaped and it is thickly padded. There are broad flaps that may be worn turned up and tied over the top of the head, or turned down to cover the ears and cheeks and tied under the chin. Most of the hats are lined with lamb’s wool, but some are lined with thick woolen cloth. Officers’ hats, while no warmer than those worn by the men, are more smartly finished.

Gloves are not standardized. They are made of cloth or leather and have wool lining. The soldiers sometimes wear their own woolen gloves or mittens underneath the Army gloves, just as they often wear their own pullover sweaters.

JANUARY 27, 1942

ASSAILS NEGRO BLOOD BAN

Special to The New York Times.

ALBANY, Jan. 26 —Assemblyman William T. Andrews, a Negro, read on the floor of the Assembly tonight a letter signed by E. Sloan Colt, from the Red Cross national headquarters in Washington, explaining why the Red Cross was refusing to accept blood from Negro donors for war purposes.

The letter stated that sufficient blood was being obtained from white donors and in view of the prejudices held by some against Negro blood, the Red Cross had adopted this policy, even though “there is no known difference in the physical properties of white and Negro blood.”

Mr. Andrews assailed the policy as a violation of the spirit of democracy.

The Assembly passed and sent to the Governor the Hanley bill permitting corporations to make contributions to the Red Cross.

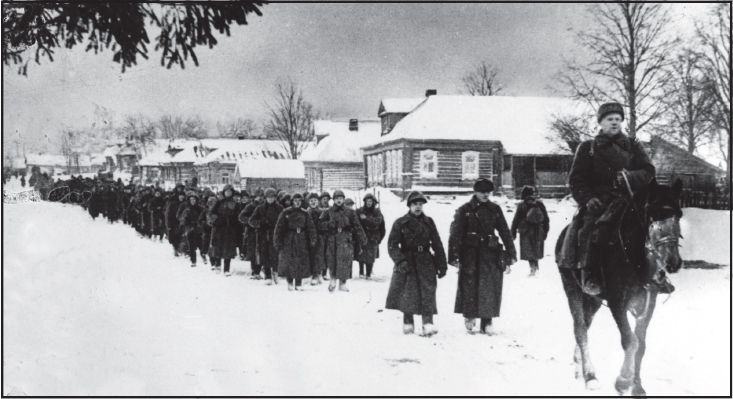

Red Army troops in 1942.

WASHINGTON, Jan. 27 (AP) —More than 1,000,000 women will be needed as skilled workers in America’s arms and munitions plants this year, Sidney Hillman, labor director of the War Production Board, estimated today.

“Airplanes can sink battleships,” Mr. Hillman said in a statement. “Women can build airplanes. War is calling on the women of America for production skills. The President has stated it is the policy of this government to speed up existing production by operating all war industries on a seven-day-a-week basis.

“Women will be called to work on the production of war materials in greater numbers than ever before.

“Women can do almost anything in wartime production. Here, as in England, they are already employed in airplane plants, ammunition plants, ordnance, fuse and powder plants.”

Mr. Hillman’s office has estimated that war industries will have to take on some 10,000,000 more workers this year, in addition to the 5,000,000 already employed, if war production goals are to be met.

Women were urged by Mr. Hillman to prepare themselves immediately for the jobs they may have to take over. He called attention to the government’s defense training programs and State employment services and urged women with factory experience to register with the latter as soon as possible.

Twenty-year-old Annie Tabor working a lathe at a large Midwest supercharger plant, making parts for aircraft engines in 1942.

JANUARY 31, 1942

BRITISH CONCEDE FALL OF BENGAZI

Report Evacuation In Face of Superior Axis Force, Which Has Seized Many Supplies

By JOSEPH M. LEVY

Special Cable to The New York Times.

CAIRO, Egypt, Jan. 30 —Despite courageous fighting by Indian troops, the jaws of a German pincers operation closed on Bengazi yesterday. Apparently greatly reinforced within the last few days, the Germans threw such numbers of tanks and mechanized infantry into the fray that British Imperial units in the immediate vicinity found themselves heavily outnumbered.

It is believed that before Bengazi was evacuated the Indians destroyed most of the supplies kept there. However, some anxiety is felt for the Seventh Indian Brigade, which was fighting south of the city, and part of it may have been caught in a German trap.

Using considerable numbers of tanks, two heavy Nazi columns had attacked the Seventh Indian Brigade well south of Bengazi. The strength of the attackers was so greatly superior that by Wednesday the Indians had to give ground. They fought bravely and clung to each position, but eventually they were driven back into the vicinity of the city itself.

JANUARY 29, 1942

U-BOATS CAUSE TEXAS BLACKOUT

Shipping Warned to Remain in Ports—Enemy Craft Signal in Gulf of Mexico

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas, Jan. 28 (UP) —A complete blackout of a 100-mile strip of the Texas coast was ordered for tonight following an announcement by Captain Alva D. Bernhard, commander of the naval air station here, that two Axis submarines were reported operating off the South Texas coast.

One submarine was seen lying on the surface of the Gulf of Mexico fifteen miles south of Port Aransas by United States patrol craft. It submerged within ten minutes after another submarine, about four miles to the east, had released a smoke bomb to warn the first U-boat. The second vessel submerged almost immediately, it was said.

A patrol of twenty-one naval planes was established at once from the Corpus Christi base and Army planes from interior Texas points were ordered to the area.

The blackout was ordered from Rockport to a point thirty miles south of Corpus Christi.

Captain Bernhard said he was authorized by the Navy Department to release the information but that any further details would have to come from Washington. He said the submarines were “probably German.”

The first announcement of the presence of a submarine was issued at Port Arthur by Commander R. R. Ferguson, naval port director there, who warned shipping that a U-boat had been sighted fifteen miles off Aransas Pass. The pass leads between two shoals into Aransas Bay, fifty miles from here, and is 130 miles north of the southernmost tip of Texas.

Commander Ferguson said it had not been determined that the submarine was an “enemy” ship, “but it may be presumed it was.”

Shipping in this area alongshore is generally quite heavy and prior to the United States’ entry into the war hundreds of tankers put out from Texas seaports.

DRIVE TO COAST ROAD

Meanwhile an even stronger Axis force reached Er Regima, sixteen miles east of Bengazi, and by nightfall Wednesday held the coast road north of the city. The Fourth Indian Division, which remained in Bengazi, was thus put into a dangerous position and it withdrew in a northeasterly direction, escaping the Nazi pincers but leaving Bengazi open for Axis occupation.

The Germans have yet to meet the large British forces operating outside the immediate region of the captured city, but considering Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s tendencies toward optimism, it is held likely that he will attempt to move farther eastward, even at the expense of another battle.

The British lost considerable amounts of material and supplies, and the Germans picked up enough British gasoline to free them temporarily from pressing supply difficulties.

Yet Marshal Rommel’s achievement in capturing Bengazi is regarded as being of scant use except to help protect his northern flank if he chooses to attempt to fight his way eastward across the desert. The ease with which Bengazi itself may be outflanked by desert operations makes its value doubtful.

MEKILI MORE VALUABLE

The British will not give up Mekili, which, much more than Bengazi, controls the Jebel el-Achdar range, without a fierce struggle, and Marshal Rommel will have a considerable communications problem if he risks an assault. Whether he will try an immediate advance depends on the extent of his reinforcements, which, though quite enough to have overwhelmed the Bengazi defenders, may be insufficient to cope with the tremendous obstacles of a long desert advance.

A substantial German force still remains in the Msus area, between Bengazi and Mekili, but activity there yesterday was confined to patrol fighting. German detachments patrolling northeastward from Msus met British patrols and withdrew. The German units in this area probably will form the spearhead of the Nazi drive if Marshal Rommel has not given up the idea of reaching the Egyptian frontier area.

FEBRUARY 2, 1942

QUISLING RECEIVES TITLE OF PREMIER

German Commissar Terboven Installs Head Of the Puppet Government of Norway

By BERNARD VALERY

By Telephone to The New York Times.

STOCKHOLM, Sweden, Feb. 1 —Major Vidkun Quisling was today proclaimed Premier of Norway by Reich Commissar Joseph Terboven. The new title did not change anything in Major Quisling’s status as puppet.

Symbolically, the ceremony took place in the sixteenth-century Aker fort of Oslo, which the Germans are using as a military headquarters and on the ramparts of which they execute Norwegians sentenced by their courts-martial.

The Norwegian capital was thronged with subordinate Quislings who came from every part of the country. All the larger hotels and houses were requisitioned for their use. There was but one exception. The building of the Royal Norwegian Automobile Club is occupied by the commander of the German troops in Norway, Col. Gen. Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, who, it is rumored, refused to allow one Quislingist in his residence.

OFFERS SUPPORT FOR ACTION

According to the summary of Commissioner Terboven’s speech issued by the Norwegian Telegraph Agency, he “produced hitherto documentary proof that Bishop Einar Berggrav of Oslo declared before the war that Britain was the enemy of Norwegian neutrality, while Germany was its friend.” Thereby, said Herr Terboven, the Bishop proved himself “a typical classical Crown witness in the question of the absolute righteousness of the policy of the Nasjonal Samling [Nazi party].

Apart from the fact that Bishop Berggrav is in no position today to confirm or deny the authenticity of this “documentary proof,” observers here point out that he led the joint protest of all Norwegian Bishops against the policies of the Samling, that courageously he has continued the struggle and that Quislingists make no secret of their intention to have his head at the first opportunity.

The German commissioner further compared the struggle for power of the German National Socialists with the attitude of Major Quisling’s party. He ended by declaring that “today this movement—the Nasjonal Samling—even from a purely numerical point of view is the strongest Norway has ever had.”

It is asserted here that the Quisling party membership does not exceed 30,000 while the old Social Democratic party in Norway had a minimum of 125,000 members.

QUISLING THANKS HITLER

Speaking in German, Major Quisling thanked “on behalf of the entire Norwegian people” Reichsfuehrer Hitler and Herr Terboven “for the understanding they have shown for the deepest desire of the Norwegian people.” Then, in Norwegian, he turned toward his countrymen and said among other things that “our movement is the only lawful Norwegian authority” and that “the foremost aim of the national government is to make peace with Germany.”

As for Sweden, Major Quisling declared that as soon as possible a change would be made in the abnormal relations by which Sweden represents the “emigre government” in protecting Norwegian interests in foreign countries. But he promised to follow an “honest and sober policy” toward Sweden.

Observers here say that the whole ceremony was entirely unconstitutional. Major Quisling was not appointed Prime Minister by the King nor did he receive a vote of confidence from the legal parliament.

Herr Terboven, who apparently will remain in Norway as chief of the German civilian administration and Major Quisling’s adviser, will continue to rule the country from the background. It is presumed that, realizing that the struggle against Norwegian opposition will become more bitter, the Germans have decided to have Major Quisling ready as an eventual scapegoat.

Vidkun Quisling, Premier of Norway’s puppet government.

FEBRUARY 9, 1942

EDITORIAL

This is an Air War

The American Army alone, it is announced, plans to create a 2,000,000- man air force. Such an Army air force would compare with a reported strength of 1,000,000 to 1,250,000 in the Nazi Luftwaffe and of about 1,000,000 in the British R.A. F. In addition to the Army’s plans. the Navy is preparing an immense air arm of its own.

These plans reveal that the Administration recognizes the tremendous and determining role that air power is going to play in this war. Even more than any other nation, the United States must concentrate on air power. The great ocean distances that have so far kept our mainland free of air attack are also the chief barriers that stand in the way of our own offensive action against the Axis. There are only two ways in which we can bring that offensive action to breakthrough long-range bombers and through ships.

We need the ships to transport men and tanks and guns and pursuit planes. But our ships are limited in number; compared with planes, they move with painful slowness, and cargo space must be rigorously economized. This means that they must only to a small extent be used to ship mere manpower; they are needed mainly to transport short-range planes, air personnel and fully mechanized divisions. If we can get these air forces and mechanized forces to Russia and China they can act as spearheads to turn the almost unlimited manpower already in these nations, particularly China, from defensive to vigorous offensive action. The merchant ship and the plane, with the protection of warships and of airplane carriers, are the two chief weapons with which America must win this war.

An air force of the huge dimensions that we now contemplate raises once more important questions in war organization. When it has grown to this size, an air force can no longer be thought of as a mere “supporting arm” to the older services. The question may be seriously raised whether in our own case the relationship will not be the reverse of this, and whether this should not be reflected in a new form of organization.

It is at least clear that at any given point the Army, Navy and air force must all be under a single unified command. And those in command of the air forces must have a thorough training in and understanding of air tactics and strategy. This training and understanding certainly did not exist at Pearl Harbor. It they had, our planes there would not have been concentrated and exposed in such a way that the Japanese were able to inflict the maximum rather than the minimum damage upon them on the ground. Our apparent lack either of sufficient airplanes or of proper protection for airplanes at Guam, Wake, and the Philippines also raises a serious question whether those in charge of strategy in Washington before Dec. 7 really understood the role of the air force and were alive to the needs of the situation.

Not less important than having a huge air force is to have men in command who know how to use it. And this must raise one more question: whether men whose whole training has been in the older services with the older weapons can be relied upon to assign air power its proper share in their plans. There has been an increasing tendency since Pearl Harbor to put in command men with a better understanding of air power. This reform must be thoroughgoing.

FEBRUARY 15, 1942

10 WEEKS OF PACIFIC WAR SHOW JAPAN UNCHECKED

Tottering Singapore Gives Foe Access to Rich Indies And Indian Ocean

By HANSON W. BALDWIN

WASHINGTON, Feb. 14 —Ten weeks ago today at Pearl Harbor the Japanese won their first major victory of the war. Last week, as thousands of fanatical little fighters swarmed across the Johore Strait on to Singapore Island they had won their second great victory—one with unpredictable implications—and the second phase of the Pacific war was ending with the Malay barrier breached and the strategic picture for the United Nations somber with defeat.

Within ten weeks the Japanese have swept to astounding triumphs. The bitter cup of the United Nations is almost full. But not to overflowing. For, to put it baldly—and that is what the people of the United Nations need, bald, frank, pitiless truth—the worst is yet to come.

There can now be no doubt that we are facing perhaps the blackest period in our history. The escape of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, the success of the German drive in Libya, which is developing into a determined and ruthless offensive, the impending Nazi offensive in Russia, and the increase in ship sinkings in the Atlantic add to the gloom of the Pacific picture. But the threats in Europe are still largely potential; in the Pacific the headlines of the newspapers have recorded their actuality.

ORIENT PICTURE IS BLACK

Singapore was the keystone of the Malay barrier. Amboina, advanced naval and air station for Surabaya in Netherland Java, has gone. Most of the ports of Borneo, with their oil fields, are in enemy hands. The Celebes have gone. The Japanese have forced a crossing of the Salween River line in Burma and are on the road to Rangoon. The picture in the Orient is black.

Singapore’s chief importance was not only as a key bastion in the Malay barrier. It was the only major naval and air base available to the United Nations in the entire Far East. Its value in this respect had been largely nullified ever since the Japanese offensive down the Malay Peninsula drove within fighter-plane range of the $400,000,000 base.

But not only was it thought to be a strong point defensively in the Malay barrier line, but as long as it remained in the hands of the United Nations it was a potential springboard for offensive operations against Japan, the kind of operations that alone bring victory. It was the only port between Calcutta, India, and Sydney, Australia, that had drydocks large enough to accommodate large men-of-war—battleships and carriers—and it possessed at least four air fields.

DRYDOCK MAY BE SAVED

The British may have been able to save something from the wreckage of disaster. The drydocks may have been towed to safety rather than destroyed. But the possibility is unlikely.

As it is, Surabaya, a second-class naval and air base on the island of Java, is now the only principal base available in the theatre of operations, and it has already been bombed several times. And Java is now the final citadel of Dutch resistance in the Netherlands Indies.

It is the most heavily defended of the Indies; there are probably the equivalent of two to four divisions, plus supporting troops (Netherland and native) on the island, and the principal Netherlands Indies air bases and air forces are there. The small forces of the Netherlands Indies Navy and of our Far Eastern naval forces are available for its defense, and behind it lies Port Darwin and the great subcontinent of Australia, now becoming a base of supplies for our Far Eastern operations.

British soldiers taken prisoner by the Japanese in Singapore, 1942.

FEBRUARY 16, 1942

BRITISH CAPITULATE

Tokyo Claims Toll of 32 Allied Vessels South of Singapore

By JAMES MacDONALD

Special Cable to The New York Times.

LONDON, Feb. 15 —Singapore has fallen.

The long dreaded news that the key British base of the Pacific and Indian Oceans would be captured by the Japanese—a major reverse clearly foreseen many days ago—was announced tonight by Winston Churchill, a few hours after dispatches from Vichy and Tokyo reported that Lieut. Gen. Arthur E. Percival’s forces had surrendered unconditionally at 3:30 P. M. today British daylight saving time [9:50 P.M. Sunday Singapore time and 10:30 A.M. Eastern war time].

London officials naturally declined to disclose what plans had been made or were perhaps in the making for establishing a naval base elsewhere to meet the grave emergency arising from the loss of Singapore. They could not or would not divulge how many Imperial troops were taken prisoner or how many got away.

COMMANDERS MEET

According to the official Tokyo announcement, fighting ceased along the entire front three hours after a meeting between General Percival and the Japanese Commander in Chief, Lieut. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, in the Ford motor plant at the foot of Timah Hill, where the documents of surrender were signed. The terms were not disclosed here, but a Japanese Domei Agency dispatch late tonight said that under the capitulation up to 1,000 armed British soldiers would remain in Singapore City to maintain order until the Japanese Army completed occupation.

Similar terms, it is recalled, were contained in the surrender of Hong Kong on Christmas Day.

The Tokyo radio said the Japanese had constantly kept pouring in fresh troops to make up for losses from the fierce resistance of British Imperial troops.

In the final battle, three Japanese columns were said to have advanced on the city. Yesterday the central column completed occupation of the water reservoirs and a part of this column reached the northern outskirts of the city on a six-mile front. Another column bypassed the reservoirs, crossed the Kalang River and cut the road from Singapore to the civil airport. The third column reached Alexandris Road in the western part of the city.

SOME RESISTING, TOKYO SAYS

[Japanese units left the main island in barges and seized Blakang Mati, the island opposite Keppel Harbor, thereby gaining control of the sea approach to Singapore from the south, according to a Tokyo broadcast recorded by The United Press.

[Japanese troops entered Singapore City today under the terms of the surrender by the British, but a Domei dispatch said some of the defending forces and “other hostile elements” still were resisting, another Tokyo broadcast heard by The United Press stated.]

The Berlin radio, quoting the Japanese newspaper Asahi, said the largest part of the British and Australian forces “obviously” left Singapore Friday for Sumatra.

Unofficial reports reached London late tonight that 2,000 persons evacuated from Singapore had arrived in Bombay.

Just about the time “cease fire” was ordered in Singapore, the city’s radio station was broadcasting as usual, giving a news bulletin and announcing in conclusion:

“This is the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation closing down its news program. We’ll be broadcasting again tomorrow evening. Good night, everybody, good night.”

Earlier in the day a Singapore broadcast had been heard in New Delhi, India, announcing, “We’re still offering stiff resistance to the enemy’s attacks.” Listeners in India had vital reason for watching the battle of Singapore because its loss involved possible domination of the Indian Ocean by Japanese naval forces. Immediate attacks in great strength on Sumatra, and other Netherlands Indies points, were also anticipated.

News of the capture of Singapore was greeted jubilantly in Japan. A Tokyo dispatch said Emperor Hirohito “heard with great satisfaction” the Japanese Imperial Headquarters announcement about the fall of the historic base that the British had held for 123 years. Both Houses of the Japanese Parliament are scheduled to meet tomorrow in a special session at which Premier Hideki Tojo and Admiral Shigetaro Shimada, Minister of the Navy, will make their official reports.

FEBRUARY 20, 1942

DARWIN IS BOMBED FOR SECOND TIME

Port Machine-Gunned in New Raid—Tokyo Reports Landing on Island of Timor

By The Associated Press.

SYDNEY, Australia, Feb. 20 —Air raid alarms sounded in Darwin today for the second successive day, but Japanese planes did not appear to follow up the two blows struck yesterday, in which fifteen persons were killed and twenty-four wounded at the vital Allied naval base on Australia’s north coast.

Air Minister Arthur S. Drakeford announced that a third raid had occurred, but later information said no enemy planes appeared although the “alert” was sounded.

[A Tokyo broadcast recorded by The United Press this morning said Japanese troops had landed on both the Netherland and the Portuguese portions of Timor, north of Australia.]

FEBRUARY 22, 1942

GUN DUEL IS HEAVY IN BATAAN BATTLE

By C. BROOKS PETERS

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, Feb. 21 —The Battle of Bataan was marked today by the growing extent of Japanese assaults upon General Douglas MacArthur’s positions in the Philippine area, the War Department reported.

During the past twenty-four hours the Japanese and the American-Filipino forces poured shells into each other’s positions in what the War Department called “heavy artillery firing.”

All along the front on the Bataan Peninsula infantry patrols were reported active and skirmishes were frequent.

Increasing and effective resistance by Filipino civilians to the Japanese invaders, and the extent to which General MacArthur’s fight is bolstered by naval men and guns and other equipment evacuated from the United States base at Cavite, near Manila, were emphasized in other communiqués.

The Japanese air force was again reported dropping incendiary bombs on objectives over and behind the United States lines. The enemy was said to have made frequent flights over General Mac-Arthur’s lines for this purpose.

The Japanese resumed firing with long-range batteries on all of General MacArthur’s defense fortifications. Fort Frank, one of the auxiliary fortresses to the bastion of Corregidor that holds the entrance to Manila Bay against the enemy bore the brunt of this artillery attack.

The Japanese have emplacements across Manila Bay at Cavite from which they have intermittently bombarded the Americans’ island fortifications. There was no indication as to the effectiveness of the Japanese shellings. The War Department reported that the harbor defense batteries returned the fire.

MAC ARTHUR HAS ‘NAVAL SUPPLY’

The Navy Department reported that the battalion of bluejackets and Marines, under the command of Rear Admiral Francis W. Rockwell, commandant of the Sixteenth Naval District, which has been fighting with General MacArthur, had succeeded in taking “considerable equipment” from the Cavite naval base before it fell to the enemy. It said also that materiel from “other sources of naval supply” has been used to good advantage in the defense of the Bataan Peninsula.

The naval equipment that is helping General MacArthur’s forces in their defense includes three-inch and four-inch artillery, as well as boats, guns and machine guns of several types, with ammunition, the Navy Department said.

In addition the Navy reported that a large number of hand grenades, aircraft bombs and depth charges, stores of gasoline, Diesel oil and lubricating oil were saved and were being used effectively in the Americas in field operations.

Motor launches and tugs were provided for General MacArthur by Admiral Rockwell’s force.

The Navy said also that the battalion had salvaged facilities for repair of artillery, tanks, and trucks, in addition to electrical and ordnance supplies.

Furthermore, the Navy reported, personnel of the naval air base organization, who were formerly employed on government contracts, has constructed and repaired airfields and roads in the fighting area. Steam shovels, tractors, cranes, trucks and graders, the Navy revealed, have been operated by this organization to useful advantage on Bataan and Corregidor.

FILIPINO CIVILIANS’ RESISTANCE

The War Department announced that General MacArthur has sent reports relative to the loyalty and morale of the Filipinos in the areas occupied by the enemy.

“Despite the harshness and severity of the military rule imposed by the invaders,” the War Department said, “the spirit of the liberty-loving Filipinos remains undaunted.”

Filipino civilian resistance to the Japanese was becoming “increasingly effective,” the report said. A secret society had been formed, the “F.F.F.” or “Fighters for Freedom,” which fostered civilian resistance to the invaders.

Informers to whom the Japanese in the Philippines have been reported as offering rewards, have been done away with by patriotic Filipinos.

Several days ago an enemy proclamation posted in Manila and throughout the countryside, enumerating offenses against the Japanese that were punishable by death and declaring that ten Filipinos would be shot for every Japanese killed, was altered overnight, the report said.

It had been changed to read that “for every Filipino killed, ten Japanese soldiers would lose their lives.”

FEBRUARY 22, 1942

INDIA’S ROLE IN WAR BECOMES VITAL

British Seek Ways To Unite People in Great Effort

By CRAIG THOMPSON

Wireless to The New York Times.

LONDON, Feb. 21 —In steady thrusts the Japanese have been pushing their way through British and Netherland Far Eastern barriers toward India and the Indian Ocean. Adolf Hitler meanwhile has been piling up ever greater quantities of guns, tanks and war chariots, which may head eastward through Turkey and Iran toward India. Since the fall of Singapore Britain has discovered, with a sharpness that has left many persons stunned, the possibility that some of this war’s most important actions may be fought out among the cool hills and hot valleys of that fabulous land of princes and Untouchables.

A junction of the Axis forces anywhere in the Middle East or Far East automatically means that the wealth of the Indies will be available to both. In this world-girdling struggle between two philosophies, Britain’s foes could hardly choose a spot where dissension and Imperial antipathy would be more likely to play into their hands. India is a place where people are torn into almost implacable groups opposed to unity on anything except a common desire to be rid of British dominance.

PRESSURE FOR UNITY

Politically, everything now is staked on the possibility that the peril of all may bring about a degree of unity in which the war effort may approach something that is closer to the potential power of the naturally rich country, with 388,000,000 people, than has heretofore been possible. There have been signs of a tendency in this direction, although India has been host to many political prophets with imported views, whose general endeavors might be classed as fifth-column work.

EXPANDING INDUSTRY

The development of war power means industrial advancement, and in this direction India has been growing by bounds since the war began, although many Indians insist that British policy has had a stunting effect.

The visit of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of China—inspired in London—was a step in the direction of unity. It was hoped that he and Madame Chiang would impress on the Indians the resilient strength of a united people, who, far from being crushed after nearly five years of warfare, have become actually stronger.

Underlying this was still another motive, seldom expressed but causing genuine concern among the British and Netherlands government; that is the power of the Japanese slogan, “Asia for the Asiatics.”

General Chiang’s visit seems to have left the situation about where it was. The Indians have given certain indications that they will drop—temporarily—some of their differences, but only on condition that the British Government lay down guarantees of post-war independence on such unqualified and specific terms that there can be no misunderstanding or recall when and if the present crisis is passed.

If the Britain Government is now prepared to make such concessions no sign of it has yet been seen in London, but there is growing anxiety about India in view of the Far Eastern developments, and it may be easily forced by the circumstances of war to make concessions. The concession, however, would be no greater than the concessions from the Indian parties in willingness to buckle down in a cooperative manner behind the war effort.

POLITICAL DIVISIONS

India has two main parties—the Moslem League, led by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, and the Congress party, which Mohandas K. Gandhi so long led and which has now been lined up behind Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, who has only been out of jail for a few months. He served nearly a year of a four-year sentence for a political speech that was deemed to be in violation of the Defense of India Rules. He was only one of thousands jailed for the same reason in the months that followed the war’s outbreak.

Nearly two years ago, when it was first proposed to establish a broad executive council under Viceroy Linlithgow, Mr. Gandhi countered with a proposal that his following insisted on guarantees of complete independence. Since these were not forthcoming he spread the doctrine of nonresistance to cover everything, including war, and even advised that Britain should lay down her arms and let Germany trample over her, and, suffering every possible indignity, refuse nothing except allegiance. The British politely replied that they appreciated the spirit in which his advice was offered but that they could not accept it.

Pandit Nehru then led a group within the Congress party who modified the nonresistance application to the essential degree that made it inapplicable to wars or national defense. But the party would have nothing less in return than guarantees of independence.