Chapter 15

“EISENHOWER RUBS HIS SEVEN-LUCK PIECES”

June–July 1943

N ews in the summer months wasdominated by the invasion of Sicily, which began on July 9 following the bombing and capture of the smaller island of Pantelleria on June 11. It was, Roosevelt announced, the “beginning of the end” for the Axis nations. This was just as well, since on the home front there were signs of growing impatience with the war effort. In June the Smith-Connally anti-strike bill was introduced into Congress to try to outlaw wartime union activity. Although Roosevelt thought the measure too extreme and vetoed it, Congress on June 26 overrode his veto and the bill became law. The domestic squabbles were soon overshadowed by the massive military undertaking in the Mediterranean.

After a news embargo, The Times finally reported on July 11 the start of the invasion. Eisenhower, noted the report, “Rubs His Seven Luck Pieces,” seven old coins (including a gold five guinea piece) that he kept in his pocket as a talisman. Times correspondent Hanson Baldwin later described the Sicily campaign as a strategic compromise, “conceived in dissension, born of uneasy alliance… unclear in purpose.” It was, nevertheless, an immediate success as Allied soldiers swarmed onto the south and east coasts of the island. Ernie Pyle, the veteran war correspondent, went ashore with the Army on a section of coast with no enemy opposition and found that the American soldiers were “thoroughly annoyed” that there was no fighting after days with their adrenalin pumping. Italian soldiers gave up quickly. Pyle thought they looked like people “who had just been liberated rather than conquered.” By mid-July General George Patton’s U.S. forces were pushing toward Palermo while Montgomery’s Eighth Army was approaching Catania, hoping to cut off the remaining German and Italian troops. Progress in the mountainous zones was slow; though Italians surrendered by the thousands, the German Army fought with its trademark skill and tenacity.

The Sicilian campaign temporarily overshadowed the Pacific and Soviet campaigns, but there was evidence in both theaters that the “beginning of the end” was no exaggeration. General MacArthur launched the start of his South Pacific campaign against the Japanese in New Guinea on June 29, hand in hand with further advances in the Solomons after the victory on Guadalcanal. On the Eastern Front Hitler’s armies launched Operation Citadel on July 5 against a large Red Army salient around the Russian city of Kursk. After making slow progress on both sides of the salient, Hitler terminated the operation when news arrived of the invasion of Sicily. The Red Army had held back large reserves that were suddenly released against the retreating Germans. The result was a devastating defeat, as German armies were ejected from Orel, Bryansk and Kharkov by late August. This was the first major defeat inflicted on German forces in good summer campaigning weather and it marked a decisive turning point in the Eastern war.

Meanwhile, the bombing of German and Italian targets continued relentlessly. Operation Gomorrah against Hamburg left 37,000 dead after a week of bombing, which included a deadly firestorm on July 27–28 that incinerated 18,000 people. In Italy the decision was finally taken to bomb Rome, the Eternal City, which had been left unscathed because of the political risks of damaging its cultural heritage or accidentally striking Vatican City. On July 19 a Times correspondent, Herbert Matthews, flew in one of the bombers to record the operation against the San Lorenzo and Littorio marshaling yards and the Ciampino air base. The headline the following day ran “Times Man from Air Sees Shrines Spared,” though Rome’s Basilica of San Lorenzo was, in fact, badly damaged. Six days later Mussolini was overthrown by a revolt of the army and some Fascist Party leaders. The Times, like many other papers, assumed that the bombing must have accelerated the decision to stage a coup, but it did not yet mean that Italy would surrender.

MANY WOMEN SHOW WAR WORK STRAIN

Signs of Fatigue, Loneliness and Sense Of Instability Noted in USO Survey

HOUSING HELD BIG FACTOR

Also Sanitation, Recreation—Trailers Present A Variety of Special Problems

Women in war jobs in various areas are beginning to show signs of fatigue and emotional strain, according to Miss Florence Williams, director of health and recreation for the United Service Organizations division of the National Young Women’s Christian Association, who returned yesterday from a six-month field trip through centers in the East, South and Midwest. She is now drafting a program to aid women white collar and factory workers.

That old adage about “all work and no play” is in evidence among women workers in factories and offices, Miss Williams said. She has noted distinct signs of loneliness and a sense of instability.

“Last year,” she continued, “most women regarded taking war jobs as a game. Today it has become a serious business. Women are showing visible signs of fatigue. In many communities, they just work and go to bed; work and go to bed. They aren’t living right or eating right. And many are working under the misapprehension that it is unpatriotic to have a good time.”

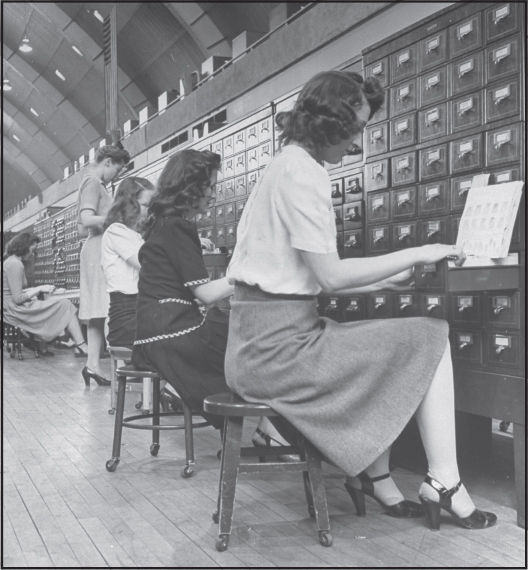

Working the file room of the FBI, 1943.

THE PRINCIPAL PROBLEMS

Chief problems noted by Miss Williams were inadequate housing facilities, with girls having to do their laundry in a tiny cubicle that is also the only place where they can receive men visitors: lack of washrooms and adequate cafeterias in both dormitories and plants; locations that offer no form of amusement or relaxation; high cost of food; long hours and too frequent changes of women workers from “graveyard” shifts to swing shifts.

Another problem arises from trailers that wind their way across the country. As many as 350 were found in one Kansas war plant community, with only seventy of these units filled.

Miss Williams, in consulting some of these families, found a distinct contrast between their point of view and that of the community. The trailerites consider themselves modern pioneers, carrying on the tradition of the covered wagon. Towns where they set down their caravans, however, frequently frown upon them. Consequently the women in the trailer colonies are lonely and unhappy, with difficulty in obtaining food added to their social problems.

The USO, Miss Williams said, is helping these colonists set up their own community law and planning committees. For those whose knowledge of child care and sanitation is deficient, the USO conducts child-care classes and teaches mothers, some as young as 16, how to enforce sanitary laws.

CONTRIBUTIONS TO ‘MELTING POT’

Miss Williams stressed, however, that persons of widely differing cultures are living in trailers parked right beside each other, and that with each group contributing its native games and customs, the trailer colony is adding to the melting pot qualities of American democracy.

Housing conditions in certain areas of Texas are so poor that women war workers have to wade through mud to get to and from their dormitories. In one part of Ohio, the only recreational center is a USO clubhouse, consisting of two rooms over stores twelve miles from the industrial dormitories.

JAPANESE EXCEL IN U.S. COMBAT UNIT

American-Born and Nizei from Hawaii Are Setting Mark at Camp Shelby, Miss.

GROUPS ARE SHOCK TROOPS

Officers Praise Highly Their Zeal for Military Training, Sports and Sociability

Special to The New York Times.

CAMP SHELBY, Miss., June 5 —Spiritedly conforming to its regimental motto, the Japanese-American Combat Team is rapidly taking shape here on the red clay drill fields of southern Mississippi. Japanese by ancestry but Americans by speech, customs and ideals, the several thousand Nisei from Hawaii and War Relocation Centers on the mainland are training for the day when they can fight shoulder-to-shoulder with other Americans against a common enemy.

“Go for Broke” is the motto they have inscribed on their self-designed and officially approved coat of arms. It is soldier slang born of dice games, and it means “shoot the works,” or risk all on the big venture before them. It was no idly chosen phrase. The Japanese-Americans realize they have perhaps more at stake in this war than the average soldier. They have known from the beginning they would be under close public scrutiny, each soldier—in the words of their commanding officer—“a symbol of the loyalty of the Japanese-American population” in our country.

WELL SUITED TO COMBAT TEAMS

By temperament, character and zeal they are admirably suited for a combat team. A combat team is a small, streamlined army able to fight its own battles without aid from other forces. The Infantry calls them combat teams, the Armored Forces call them combat commands and the Navy calls them task forces. They do essentially the same thing—specific jobs, operating often independently of other units.

The Nisei are proud to be chosen for a combat team. Young, mostly unmarried and with all the makings of combat team troops, they are keen for action and anxious to make good. Among themselves they boast they have “a year and three minutes to live—a year of training and three minutes of action.” Already they have the psychology of shock troops.

Officers training the Japanese-Americans without exception praise the attitude and early soldierly bearing of the Nisei. For the most part these officers are having their first contact with soldiers of Japanese ancestry. Said one lieutenant: “Once in a while you may have to tell them something twice, but not often. They are so eager to learn they are constantly attentive and usually get it the first time.” Another company officer commented: “I’ve been in the Army twenty-six months and I’ve never seen a group of soldiers with less griping than this organization. And as for profanity, it simply doesn’t exist.”

About thirty company officers are Nisei, the rest Caucasian.

AVID FOR MANUAL OF STUDY

Even off the drill field, the Nisei constantly seek to better themselves by study of manuals and technical books. One bookstore in nearby Hattiesburg is reported to have done about $2,000 worth of business during the first month after the arrival of the Japanese-Americans, selling them textbooks and other works on military subjects, some at prices ranging up to $5 apiece. Recently during a weekend visit of 100 Japanese-American girls from a Relocation Center in Arkansas a sizable group of Nisei were observed in a nearby field practicing grenade throwing, entirely aloof to the presence of femininity.

The Nisei are proud, too, that the Combat Team is 100 per cent an organization of volunteers. In fact, thousands more volunteered than the prescribed quota. Many applicants who were turned down actually wept in disappointment. Many quit high-paying jobs in Hawaii to enlist, and some left wives and children in the islands.

Typical, too, is the reasoning of Private Tadashi Morimoto of Honolulu, a social worker, a graduate of the New York School of Social Work. Private Morimoto in 1940 served six months in the Psychiatric Clinic of the Manhattan Children’s Court in New York. “In Hawaii,” he said, “I met a soldier from New York. He was homesick for his wife and children. He said he hoped for nothing more than an early victory so he could return to civilian life, enjoy his family and his old job. Suddenly it occurred to me that this soldier not only wanted the very things I did, but he was willing to fight for them. Why then should I sit back and let someone else fight for the rights and privileges I myself cherish? I didn’t want anyone else to do my fighting for me. My wife concurred, so I enlisted for the Combat Team.”

From a mainland volunteer came this succinct statement: “We are anxious to show what real lovers of American democracy will do to preserve it. Our actions will speak for us more than words.”

On the post the Japanese Americans already have made a name for themselves in athletics, with their musical talent and in war bond buying. The Combat Team, in two days and with no more than a suggestion from company commanders, bought $101,550 worth of war bonds, putting their cash on the barrelhead.

The Combat Team has two baseball teams, both near the top of one of Shelby’s leagues.

Sentiment, too, runs high among the troops from Hawaii. On Mother’s Day they sent 247 telegrams to the islands at an average cost of $2 a message. A thousand more sent air-mail letters, and many others inquired about personal telephone calls.

Commanding the Combat Team is Colonel Charles W. Pence, who was born in Illinois and served overseas in the First World War in the Fourth Division. Colonel Pence also served for four years with the famous Fifteenth (Can Do) Infantry Regiment in China. Before coming here last February he commanded a regiment at Fort McClellan, Alabama.

Second in command is Lieutenant Colonel Merritt B. Booth, also born in Illinois but who entered West Point from New York and came to the Combat Team from foreign service.

ALLIES PLANT FLAG ON FIRST MEDITERRANEAN STEPPING-STONE

ISLAND IS OCCUPIED

The Italian ‘Gibraltar’ is Knocked Out By Record Avalanche of Bombs

ALL GUNS SILENCED

Troops Take Over in 22 Minutes as New Design in Warfare Emerges

By DREW MIDDLETON

By Wireless to The New York Times.

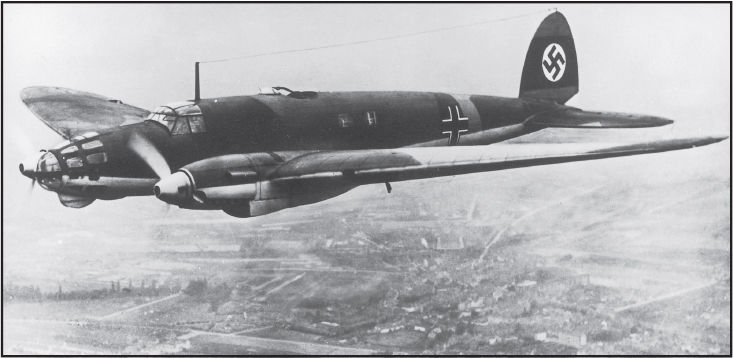

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, June 11 —Blasted into ruins by hundreds of tons of bombs, the Italian island of Pantelleria, the last Axis stronghold in the Sicilian Strait, surrendered to overwhelming Allied air power this morning rather than endure another day of death and destruction under the most concentrated aerial attack in the history of warfare.

Allied assault craft darted ashore at noon soon after air crews had sighted a white cross of surrender on the airfield and cruisers and destroyers that supported the landing had spied a white flag flying from Semafore Hill, 2,000 yards from the Harbor of Pantelleria. There was slight resistance from Axis troops, dazed by thirteen days of continuous bombing, and all primary objectives were reached by 12:22 P.M. [London estimates placed the garrison at 8,000 Italians, The Associated Press said.]

It was evident that the island was so disorganized by the bombing and frequent shelling by British cruisers and destroyers that news of the surrender had failed to reach all the enemy troops on the island although the commander had surrendered by displaying the white flag and white cross.

GERMAN DIVE-BOMBERS ROUTED

British troops scrambled up the rocky beaches past wrecked gun batteries—the last enemy gun was silenced by dusk yesterday—and the people of the island crept from shelters to watch with eyes dulled by fear.

[Within an hour after the surrender of Pantelleria, fifty to sixty German dive-bombers attempted to break up the landing forces, but Americans in Lightning fighters routed the Germans, forcing them to jettison their bombs haphazardly in flight, The Associated Press reported. An Algiers broadcast said that naval and infantry casualties in the occupation were negligible.]

The major share of credit for opening the first breach in Italy’s chain of island strongholds goes to air power, such air power as never before had been concentrated on a target of similar size.

The climax came yesterday when more bombs were dropped on the island than were dropped in the entire month of April on all targets in Tunisia, Sicily, Sardinia and Italy.

As great a weight of bombs was unloaded on the island in the intensified aerial offensive from May 29 to June 10 as was dropped on all targets in the African theatre in the month of May. And this round-the-clock assault was preceded by six days of heavy intermittent attacks.

YIELDED AFTER THIRD DEMAND

The capitulation in the form of the white cross on the airfield came as formations of Flying Fortresses, Mitchells and Marauders were over the island. Two previous requests to surrender were ignored by the commander of the Axis garrison. Once emblems of surrender were sighted by the Allied air and naval forces [at 11:40 A.M., according to The Associated Press], the Allied military commander started occupation of the island.

[The surrender also was made known by Admiral Paresseni, senior Italian officer on the island, in a message to an American air base, saying, “Beg surrender through lack of water,” The Associated Press said.]

Lieut. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Commander in Chief of the Allied forces in North Africa, and Admiral Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham, Naval Commander in Chief for the Mediterranean, were on the bridge of the famous British cruiser Aurora when she led a fleet of four other cruisers and eight destroyers in the bombardment of Pantelleria on Tuesday. The Aurora steamed close inshore to test the fire of the Italian shore batteries.

SHELLS HIT NEAR CRUISER

The Allied Commander in Chief and Admiral Cunningham watched the dramatic naval and air assault, which came to a climax at noon when motor torpedo boats dashed into the harbor of Pantelleria on a test run. While the squadron was waiting for the small craft to reappear, shells from the big Italian shore batteries fell within 300 yards of the Aurora.

When the naval bombardment and aerial pounding were over for the day, General Eisenhower said there was “no doubt” that the island would fall “once the infantry gets in their part.”

The surrender was the first in the war by a fortress of the size of Pantelleria to air power supported by sea power, without serious action by ground forces.

American bombers and fighter bombers, which bore the main weight of the Allied attacks on Pantelleria, also contributed heavily to the campaign of attrition against the Axis fighters in this theatre. Thirty-seven enemy fighters were shot down by American airmen over Pantelleria yesterday. In the last thirteen days of the offensive seventy-eight enemy planes were destroyed in combat against an Allied loss of twelve.

The shattering attack delivered yesterday eclipsed anything done before in this theatre. The greatest number of Flying Fortresses ever employed in this area led the attack on the island, dropping hundreds of thousand-pound bombs. It is estimated that well over a thousand sorties were flown by the Allied airmen. The assaults, which started with dawn and ended at the approach of dusk and a thunder-storm, dropped a load of bombs that no other target of similar size ever sustained in one day. The night before heavily loaded Wellington medium bombers and Hurricane fighter-bombers of the Royal Air Force had hammered the island as a prelude to the great assault to come.

During the day traffic over the island, which was marked by a heavy cloud of smoke that lay above it, was so heavy that the bomber formations had to circle the island waiting their turn to make “a pass” at the target.

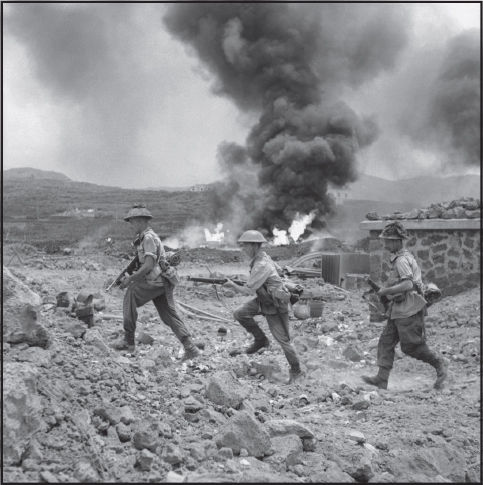

British troops in Sicily, 1943.

The aerial offensive against Pantelleria was “a test-tube attack” that went beyond the original objective of battering the island defenses to a point where A1lied troops could land to force complete surrender of the island. Although sea power gave valuable support and the ground forces were ready when the time came, it was air power that conquered the vital, strongly defended fortress.

GREAT POWER THROWN AT TARGET

In the culmination of the air attack yesterday Flying Fortresses, Marauders, Mitchells, Bostons, Baltimores, Lightning and War-hawk fighter-bombers and Spitfire fighters from the Allied air forces took part in day-long attacks.

The progress of the offensive was worked out on a mathematical pattern, with the weight of bombs and number of aircraft gradually increased each day from May 29 until the knockout punch was delivered yesterday and this morning following the refusal of the island’s commander to surrender. Another request for unconditional surrender had been dropped on the island yesterday after the two previous ones had been ignored.

Hundreds of hits were made on military installations, batteries, range finders, barracks and gun positions all during yesterday’s bombing. Several large explosions, probably the result of bombs hitting ammunition dumps, were reported.

When the Boston, Baltimore and Mitchell bombers of the United States Army Air Force and Royal Air Force began their attacks yesterday morning they found antiaircraft fire was negligible and encountered no enemy fighters. Between sorties by light and medium bombers, fighter-bombers attacked targets at fifteen-minute intervals, sweeping in at low level to top off the destruction started by high-level attacks.

Pilots and crews returned from Pantelleria impressed by the destruction down below. First Lieutenant Melvin Pool of Durant, Okla., called it “a damned good show” and said he believed the Fortresses “had the bases loaded and knocked a home run.” Wellingtons attacking the night before had started several fires, some of them very large, in the Pantelleria harbor area.

Studded with heavy gun batteries well concealed in and behind cliffs along the coast, Pantelleria was believed impregnable by the Italians. Benito Mussolini wrapped the island in a cloak of secrecy after 1937, when he announced that naval and air bases were being built there. Landings were forbidden on the island except for Italian military, naval and air personnel, and a decree forbade flight over it or adjoining territorial waters.

Bit by bit this island fortress, two-thirds the size of Malta, was knocked apart. Bombers, began by wrecking the airfield in the early days of the offensive, destroying numerous planes on the ground.

Then every ship in the harbor either was sunk or damaged so severely that she was useless.

Gun batteries were next. One by one the emplacements were bombed by Flying Fortresses and medium bombers, while fighter-bombers attacked from lower levels. Meanwhile, a complete sea blockade was achieved and the enemy fighter fleet based on Sicily was unable to check the steady progress of the offensive.

The enemy made his greatest defensive effort yesterday in the day of aerial operations that undoubtedly will become a classical example of the exertion of air power.

ENEMY ATTACKS FROM SICILY

Drawing from fighter squadrons based on-Sicily, the enemy attacked Allied bombers heavily from mid-morning to dusk. Marauders of the Strategic Air Force and an escort of Warhawks were intercepted over Pantelleria by Axis fighters. The Warhawks got five enemy planes and the bombers destroyed one in a running fight that lasted from the target to near the African coast at Cap Bon.

Captain Ralph Taylor of Durham, N.C., shot down two Messerschmitt 109’s in this engagement.

American Spitfire pilots of the Tactical Air Force destroyed twelve Italian and German aircraft. One squadron knocked five enemy planes out of the skies in the morning while another squadron of the same group shot down seven more in the late afternoon. The group as a whole destroyed seventeen aircraft June 9 and 10, and lost only one plane.

Thirteen Macchi 202’s dived on Allied bombers that the Spitfires were escorting to open the afternoon battle. The Spitfires gave chase and intercepted the Italians before they reached the bombers. The dogfight was joined by six Messerschmitt 109’s and three Focke-Wulf 190’s.

The Italians were being knocked down so fast that the Spitfire squadron commander, Major Frank Hill of Hillsdale, N.J., said he counted four enemy parachutes in the air at one time.

“And down below us,” he added, “I could see I don’t know how many splashes in the Mediterranean where their aircraft were crashing,” Major Hill destroyed a Macchi 202, his sixth victory of the war.

Lightning fighter-bombers led by Lieut. Col. John Stevenson, West Point graduate from Laramie, Wyo., fought a brief action with several Messerschmitts, destroying one. So many pilots pumped lead into an enemy plane that it “went down as a squadron victory, and that makes everybody happy,” according to Colonel Stevenson.

Altogether twenty-six of thirty-seven enemy aircraft destroyed over Pantelleria were knocked down by the Tactical Air Force. Marauders of the Coastal Air Force operating near the coast of Italy yesterday shot down two Messerschmitt 109’s, increasing the day’s victory total to thirty-nine. Six Allied planes were lost.

The highest scorer in the American Spitfire unit is Lieutenant Sylvan Feld of Lynn, Mass., who on June 6 shot down a German plane to bring his total of victories to nine, all scored since March 22.

JUNE 20, 1943

CRITICAL PERIOD AT HAND IN HOME-FRONT CONFLICT

War Crises in Mining, Wages, Food and Inflation Reflect Uncertainties Of the National Effort

BYRNES, BARUCH TO THE FORE

By ARTHUR KROCK

WASHINGTON, June 19 —The most critical period on the home front since the United States entered the war is at hand. Whatever may be the immediate solutions of such emergent matters as the wages of the United Mine Workers, some weeks must elapse before it will be possible to determine with certainty whether the Administration will be able to support the military forces with supplies produced at an expanding rate and at anywhere near the present levels of cost.

On the outcome of the group conflicts now raging depend also the morale of the home front and, to some extent, that of the armed services. Conditions in the various areas of dispute which constitute a battlefield on which the struggle will, in the next few weeks, be won, lost or compromised—harmfully or destructively—are about as follows:

Food —Unfavorable weather, a price system in several respects ill-conceived, depletion of farm manpower, restriction of farm machinery and of the reproductive elements in agriculture have combined with a loose and confused administration of food controls by Washington to bring about a menacing situation. Among examples of what is happening in this sector is a report by Senator Scott Lucas of Illinois that farmers are holding 900,000,000 bushels of corn in their bins awaiting a price adjustment; a depressing crop report by the Department of Agriculture, and an assertion by Chester C. Davis, Food Administrator, that serious food shortages are certain. It has been predicted that between the time of the next spring planting and the 1944 harvest some of these shortages will be acute.

REFORMS MAY BE FORCED

Many remedies have been proposed, and some will be attempted during the critical period on which the nation is now entering. There are definite signs that the War Department has revised downward the size of the Army planned for the end of 1943, which should relieve the drain on the manpower that produces and processes food. The President has rejected proposals that all Federal food controls be merged under the Secretary of Agriculture, replacing the incumbent, Claude Wickard, with Mr. Davis; and he has also declined to break up the Office of Price Administration or cause a revolutionary change in its pricing policies.

Plans are proceeding to institute a broad system of Federal subsidies to maintain consumer prices of certain foods and push down the prices of others to the level of several months ago. No one authority agrees with another as to the ultimate cost of such a program, the guesses ranging from Price Administrator Prentiss Brown’s of less than a billion to the President’s of a three billions maximum. Food-producing groups, their spokesmen in Congress and outside citizens who fear that politics will mix with economies in the use of subsidies are resisting the project But the general belief is that the present limited subsidy program will be expanded by the Administration in an effort to win the adherence of organized labor to the President’s hold-the-line program.

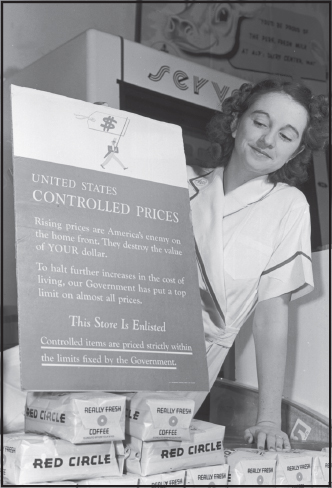

A store clerk next to a sign supporting government-controlled prices during the war.

Wages —Despite the common national peril and military effort, the attitude of organized labor toward legal restraints invited by its own excesses and toward the employing group remains hostile. Only this week A. F. Whitney, president of the Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen, denounced the railroad managers as swollen with war profits and conspiring to create the greatest monopoly in American history after the war has ended. He said that in opposing wage increases and rate decreases at the same time, the managers are about “as reasonable as an alley-cat with a hunk of raw meat.”

ATMOSPHERE OF HOSTILITY

This same atmosphere of hostility between employees and employers surrounds other industrial areas in a time when good-will would amount to a military asset. Mr. Whitney is known as a “maverick,” not representative of the general attitude of railway labor.

Yet his outburst, coming from a source where labor relations have been more harmonious than in any other, emphasizes the spread of ill-feeling. The President has done much to foster economic and social class resentment, and in this respect his own chickens are coming home to roost. But it is the whole country and the war program that must pay the price.

The philippics of John L. Lewis toward the employers of coal miners have been almost a part of the daily news record for the last few weeks. In purple phrases he has drawn a picture of hungry workers and undernourished children, victims of rich and heartless coal operators who would be complimented by the names of war profiteer, cormorant or vulture. This language is only part of Mr. Lewis’ tactics when he is fighting for a wages rise. But the effect on the workers is to stimulate a feeling of bitterness toward those who pay their wages, and this contributes to the critical situation in which the nation finds itself. How much it is ameliorated by the reiteration Friday of the “no strike” pledge by Van Bittner, Daniel Tobin and other labor leaders remains to be seen.

WEIGHING THE REMEDIES

As this is written, and probably when it shall have been published, the ultimate solutions of the conflicts over mine wages and the anti-strike bill are not in sight, though stop-gap methods may be discovered in the interim. But not for some time will it be possible to measure the effects or durability of the remedies. And only when that measurement can be made with some accuracy will it be discerned whether the American people have passed from a most critical period into a worse one, or into improved conditions that will make it possible to hasten victory and keep down the cost in life and treasure.

Mr. Lewis defied the jurisdiction of the War Labor Board, and, braced by the President through the Office of War Mobilization, by Congress with the anti-strike bill and by many evidences of popular support, the board stood firm against Mr. Lewis. If he is routed by the various processes, his power as a labor leader will be destroyed for some time, perhaps forever. But his tactics have brought him to the point where his rout must be total or he will continue to make difficulties in labor ranks and prolong the critical period. He has won every other battle in which he has engaged since the President took office, at first within and then without the political structure of the Administration. This fact will impel sound observers to make more than an instant test of the effects on Mr. Lewis’ influence of events in the next few days.

THE BATTLE OF INFLATION

Inflation —This dubious battle will be decided in the areas of conflict over food, prices and wage controls as outlined above. As they go, it will go.

Next to the President, the burden of resolving the critical period into one of progress falls upon James F. Byrnes, chairman of OWM. But signs are innumerable that the country is looking behind him to his eminent official adviser, B. M. Baruch. If the line holds and goes forward, the pair will be given credit for much of the victory, and vice versa. But if the line is broken, by Presidential concessions and related causes, Mr. Baruch will be expected either to accept a share of the blame or divest himself of it by retiring from his first official post since 1920.

JUNE 21, 1943

Escort Carrier Helps Convoys Win Five-Day Battle with U-Boat Packs

New Type of Protective Vessel Instrumental In Destruction of Enemy Raiders—Land-Based Planes Also Play Big Part

By JAMES MacDONALD

By Cable to The New York Times.

LONDON, June 20 —Illustrating why the month of May was one of the best for Atlantic convoys to Britain since the closing days of 1941, officials gave out today an exciting account of a bitter five-day fight against enemy U-boats in which warships and planes from a carrier and shore stations sank two submarines, probably destroyed three more and are believed to have damaged many others.

Ranging over hundreds of miles of ocean, including the particularly dangerous area in mid-Atlantic beyond the reach of land-based planes, the struggle marked one of the fiercest and most sustained attempts ever undertaken by U-boat packs to prevent ships and supplies from reaching this country. The ships were so well protected that the majority of the U-boats were kept well out of the range of their intended victims. Some did get within range, however, but they scored on only 3 per cent of the vast merchant fleet involved.

A new technique in anti-submarine warfare was responsible for the fact that the losses were small, considering the intensity of the attack. An important role was played by one of the British Navy’s newest weapons—the pocket aircraft carrier, known officially as the escort carrier.

This vessel was H.M.S. Biter, a former merchant ship built in the United States and transformed into a floating air base for the special purpose of closing the “air gap” in mid-Atlantic where U-boats were formerly immune to blows from the air. The Biter was commanded by Captain Abel Smith, a kinsman of Queen Elizabeth and former equerry to King George. He was a member of the royal party on its tour of Canada and the United States in 1939.

The fight began, according to a joint communiqué issued by the Admiralty and the Air Ministry, when two U-boats in a big pack were sighted far out in the Atlantic by navy planes that had taken off from the Biter. The planes attacked the submarines with depth charges and machine-gun fire, forcing them to dive.

Later, after the convoy had proceeded so far that it was within reach of land-based planes, its protection was increased by Royal Air Force Coastal Command forces. First blood was drawn by an RAF Liberator, which disabled one U-boat while it was fifteen miles from the surface ships.

Meanwhile, Navy planes were busy with another U-boat. They sent word to H.M.S. Broadway—formerly the U.S.S. Hunt, one of the fifty destroyers transferred to Britain in 1940—and the frigate Lagan, one of Britain’s latest-type special-duty warships, and guided them to the scene. The destroyer and the frigate took turns attacking the submarine. The Broadway struck twice, and, after its second attack, there were muffled undersea explosions that shot wreckage bearing German markings to the surface. The communiqué said that the U-boat was considered sunk.

As the hours wore on, more Coastal Command planes, including Flying Fortresses, Catalinas and Sunderlands, arrived to protect convoys. Further fights with submarines followed in quick succession. In one of these actions, the destroyer Pathfinder hurled depth charges at a U-boat that surfaced for a brief moment and then disappeared beneath the waves. Its fate was not determined. Later, a Sunderland plane guided the Lagan and the Canadian corvette Drumheller, which has been on active service in the Battle of the Atlantic for three years, to a U-boat that received similar treatment. The spot where that submarine had been seen going down was covered by wreckage and a steadily widening oil slick that covered an area of almost four square miles the next day.

While these scraps were going on, another convoy found itself threatened by a U-boat pack ahead of it. The destroyer Hesperus sighted one enemy submarine on the surface, steering straight for the convoy. The Hesperus commenced an attack with gunfire, scoring repeated hits and blowing the U-boat’s gun-crew into the sea.

Closing in for the kill, the Hesperus let go depth charges. The U-boat either dived or sank out of control. The destroyer threshed across the spot where the enemy had last been seen, dropping a final “pattern” for good measure. The submarine’s fate was uncertain.

Soon afterward the Hesperus spotted another U-boat on the surface. She attacked the enemy with gunfire, then rammed him and probably destroyed him. While the submarine was being gunned, several members of its crew were seen jumping overboard. Whether they were rescued was not reported. The next day the Hesperus attacked still another U-boat, which disappeared amid an oil slick and floating wreckage. Meanwhile, aircraft maintained unceasing patrol over and in the vicinity of the convoys, compelling the undersea raiders to remain submerged well out of harm’s way and to lose track of the prospective victims.

JUNE 26, 1943

CONGRESS REBELS

President Is Defeated by 56 to 25 In Senate, 244–108 in House

SWIFT VOTE TAKEN

Criminal Penalties Are Made Law, But 30-Day Strike Vote Is Set

By W. H. LAWRENCE

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, June 25 —A rebellious Congress, angered by three coal strikes and other sporadic interruptions of war production, quickly overrode President Roosevelt’s veto today and enacted into law the Smith-Connally anti-strike bill requiring thirty days’ notice in advance of strike votes and providing criminal penalties for those who instigate, direct or aid strikes in government-operated plants or mines.

The Senate voted 56 to 25 to make the bill law despite the Chief Executive’s disapproval. The House voted 244 to 108 immediately afterward. Both votes were well over the constitutional requirement of a two-thirds majority to override a veto.

Both Houses acted not only quickly, but with a minimum of discussion to reject the President’s warning that the measure would stimulate labor unrest, give governmental sanction to strike agitation, and foment slowdowns and strikes.

HOW THE PARTIES DIVIDED

In the Senate, twenty-nine Democrats, including the acting Majority Leader, Senator Lister Hill of Alabama, and twenty-seven Republicans voted to override the President’s veto, and nineteen Democrats, five Republicans and one Progressive voted to sustain it.

Of the Senators who voted after the veto message had been read and who had been recorded on the conference committee report, not one changed his vote as a result of Presidential disapproval of the measure. Senator Joseph Ball, Republican, of Minnesota, who had been paired for the bill but did not vote at the time the conference committee report was taken up, voted to sustain the veto.

In the House 130 Republicans and 114 Democrats voted against the President. Of those who voted to sustain the veto, sixty-seven were Democrats, thirty-seven were Republicans, two Progressives, one Farmer-Laborite and one member of the American Labor party. Advocates of the bill gained twenty-five votes between approval of the conference committee report and the veto action, while opponents of the measure lost twenty-one supporters.

LAW GOES INTO EFFECT AT ONCE

The measure, which had been bitterly opposed by all organized labor, is effective immediately and until six months after the conclusion of the war, and contains these provisions:

The President receives authority to take immediate possession of plants, mines or other production facilities affected by a strike or other labor disturbance.

Wages and other working conditions in effect at the time a plant is taken over by the Government shall be maintained by the Government unless changed by the National War Labor Board at the request of the Government agency or a majority of the employees in the plant.

Persons who coerce, instigate, induce, conspire with or encourage any person to interfere by lockout, strike, slowdown or other interruption with the operation of plants in possession of the Government, or who direct such interruptions or provide funds for continuing them shall be subject to a fine of not more than $5,000, or to imprisonment for not more than one year, or both. The penalty clause does not apply to those who merely cease work or refuse employment.

SUBPOENA POWER FOR NWLB

The NWLB receives subpoena power to require attendance of parties to labor disputes, but NWLB members are forbidden to participate in any decision in which the member has a direct interest as an officer, employee or representative of either party to the dispute.

Employees of war contractors must give to the Secretary of Labor, the NWLB and the National Labor Relations Board notice of any labor dispute which threatens seriously to interrupt war production and the NLRB is required on the thirtieth day after notice is given to take a secret ballot of the employees on the question of whether they will strike.

Labor organizations, as well as national banks and corporations organized by authority of Federal law, are forbidden to make political contributions in any election involving officials of the National Government, with the organization subject to a fine of not more than $5,000 for violating the act and the officers subject to a fine of not more than $1,000 or imprisonment for not more than one year, or both.

The President waited the full ten days of the constitutional period before vetoing the measure which was sent to him by a 219-to-129 House vote and 55-to-22 Senate vote. At 3:13 P.M. his veto message was read to the Senate, and by 5:28 P.M. the measure was law.

SENATE IS FIRST TO ACT

The Senate acted first, with Senator Connally of Texas taking the floor to say:

“I am sorely disappointed. The Senate is sorely disappointed. The House, I am sure, is disappointed. The people of the United States by an overwhelming majority are disappointed. The soldiers and sailors wherever they may be, on land, on the sea, in the air, all over this globe are disappointed.

“The section of the bill to which the President objected was in the House provisions.

“The President has a right to veto legislation. The Senate has a right to pass a bill over the veto.

“I hope that the Senate now will exercise its constitutional privilege.”

Senator Carl Hatch, Democrat of New Mexico, seconded the motion, and the roll-call began.

When the vote was announced as 56 to 25 to override, there was applause from the galleries, led by men in uniform.

The large House majority in favor of overriding was apparent as soon as word of the Senate action reached it. A Commodity Credit Corporation extension and modification bill was up for consideration and members immediately began to move that this either be laid aside or that debate close and immediate action be taken on it, thus to clear the way for consideration of the veto.

APPEAL FOR ACTION CHEERED

Representative Clifton Woodrum, Democrat, of Virginia, received repeated applause and cheers for his plea for “action, not tomorrow, not Monday, but today, so that we can send the message to our boys in the foxholes that the American people are behind them.”

Chairman Andrew J. May of the House Military Affairs Committee, which brought out the original draft of changes in the Senate bill to which the President objected so vigorously, repeated the same thought, bringing objections that he was out of order and “trying to create a lynching spirit in the House.” The latter assertion came from Representative Vito Marcantonio, American Labor, of New York.

Apparently sensing the House insistence on action today, Representative John W. McCormack of Massachusetts, the majority leader, quickly promised that the veto message would be taken up as soon as the pending bill was dis-posed of. Delaying tactics by other Administration supporters in seeking record votes on amendments to the CCC bill failed to find sufficient House support to be effective and a motion made at 4:50 that the House adjourn was overwhelmingly shouted down. The veto message was then read, and the vote taken immediately.

SAYS STRIKES WON’T BE TOLERATED

The President’s veto message firmly declared that the Executive would not countenance strikes in wartime and was conciliatory in its approach to Congress.

Declaring it was the will of the people that for the duration of the war all labor disputes shall be settled by orderly, legally established procedures, and that no war work shall be interrupted by strike or lockout, the President said that the no-strike, no-lockout pledge given by labor and industry after Pear1 Harbor “has been well kept except in the case of the leaders of the United Mine Workers.” During 1942, he said, the time lost by strikes averaged only 5/100ths of 1 per cent of the total man-hours worked, a record which he declared had never before been equalled in this country and which was as good or better than the record of any of our allies in the war.

He conceded that laws often are necessary “to make a very small minority of people live up to the standards that the great majority of the people follow” and in this connection he cited the recent coal strike.

FAVORS FIRST SEVEN SECTIONS

Analyzing the bill, section by section, he said that the first seven sections, “broadly speaking,” incorporate into statute the existing machinery for settling labor disputes and provide criminal penalties for those who instigate, direct or aid a strike in a government-operated plant or mine. Had the bill been limited to this subject matter, he said that he would have signed it.

His principal objection was to the eighth section, which, he said, would foment slowdowns and strikes. That section provides a thirty-day notice before a vote to strike can be taken under supervision of the National Labor Relations Board, and, while Congressional sponsors called this a “cooling off” period, Mr. Roosevelt contended that it “might well become a boiling period” during which workers would devote their thoughts and energies to getting pro-strike votes instead of turning out war material. “In wartime we cannot sanction strikes with or without notice,” he declared. “Section 8 ignores completely labor’s ‘no-strike’ pledge and provides, in effect, for strike notices and strike ballots. Far from discouraging strikes, these provisions would stimulate labor unrest and give government sanction to strike agitations.”

DRAFT CHANGE RECOMMENDED

The President was highly critical also of Section 9, which prohibits, during the war, political contributions by labor organizations. This section, he remarked, “obviously has no relevancy” to an anti-strike bill. If the prohibition on trade union political contributions has merit, he expressed the belief that it should not be confined to the war. Congress, he added, might also give careful consideration to extending the ban to other non-profit organizations.

The President reiterated his recommendation that the Selective Service Act be amended to provide noncombat military service for persons up to the age of 65, declaring that “this will enable us to induct into military service all persons who engage in strikes or stoppages or other interruptions of work in plants in the possession of the United States.”

“This direct approach is necessary to insure the continuity of war work,” he said. “The only alternative would be to extend the principle of selective service and make it universal in character.”

Whether enactment of the bill would cause the withdrawal of labor representatives from NWLB was an open question. Many persons in Washington thought that it would, but no responsible leader of labor would commit himself on this question tonight.

A NEW BILL AIMED AT EMPLOYERS

After Congress, by overriding the veto, had enacted into law the section banning contributions by labor organizations to which the President had objected, Senator Hatch introduced a measure forbidding similar political contributions by associations of employers.

It was the eighth time that Congress had overriden President Roosevelt by a veto during the more than ten years he has been in office, and it was the most important measure on which the Congress acted independent of the Executive since payment of the soldiers’ bonus was authorized, January 27, 1937.

Observers on Capitol Hill believed that the continued absence from work of a large number of coal miners, despite the back-to-work order of the UMW policy committee, and the lukewarm reception by Congress to the President’s draft proposal, played a major role in the decisive votes. There was a roar of protest on the floor of the House when the President reiterated his proposal to increase the draft age to 65 to deal with strikers.

Many members of Congress expressed dissatisfaction, saying that coal mine owners were being punished by being deprived of their property, although it was the union, and not the employers, which had defied the NWLB and called strikes.

Another cause of restiveness among members was the fact that John L. Lewis, in ordering the miners back to work, set another deadline for Oct 31, and said his decision to work on the Government’s terms was predicated on continued Governmental operation of the mines.

JULY 1, 1943

M’ARTHUR STARTS ALLIED OFFENSIVE IN PACIFIC; NEW GUINEA ISLES WON, LANDINGS IN SOLOMONS; CHURCHILL PROMISES BLOWS IN EUROPE BY FALL

UNITED NATIONS FORCES MOVE FORWARD IN THE SOUTHWEST PACIFIC

By SIDNEY SHALETT

Special to The new York Times.

WASHINGTON, July 1 —Combined Army and Navy forces under General Douglas MacArthur have opened the long expected offensive against the Japanese in the south and southwest Pacific.

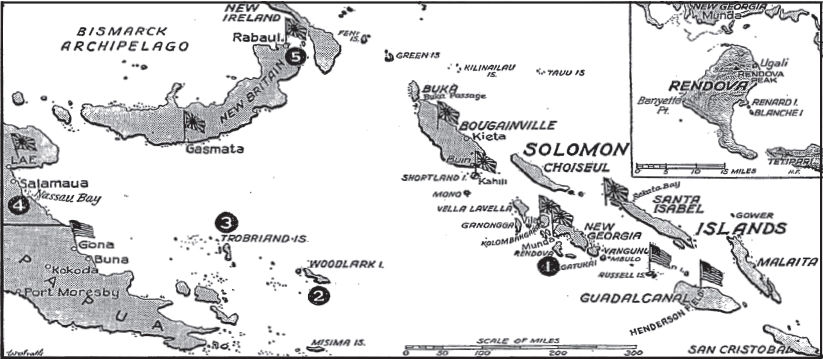

Fighting was in progress on Rendova and New Georgia islands, which were hit by ground, naval and air forces in “closest synchronization,” a communiqué from General MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia reported today. Nassau Bay, ten miles south of the big Japanese base of Salamaua in New Guinea, fell to the Allies after a slight skirmish, and the Tobriand and Woodlark island groups, 300 to 400 miles west of the New Georgia group, were occupied without opposition.

The Allied push—aimed, observers here believe, at the major Japanese base of Rabaul, on New Britain Island—got under way yesterday, Solomons time, which was Tuesday here.

NUTCRACKER MOVE SEEN

It was believed here, on the basis of early reports, that the fighting and occupations reported so far were preliminary to major actions to come. If bases in the New Georgias are consolidated, a two-way push against Rabaul might be developing, with one arm advancing northwestward from the Central Solomons and the other swinging across eastward from new bases in New Guinea.

United States heavy bombers carried out an attack on Rabaul during the night, dropping nearly twenty-three tons of high-explosive, fragmentation and incendiary bombs throughout the dispersal areas at the Vunakanau and Lakunai airdromes, the communiqué from Australian headquarters reported. “Several explosions” and “numerous fires” were observed, one of which was visible for 100 miles, the announcement said.

United Nations Forces Move Forward in the Southwest Pacific: American troops landed on Rendova and New Georgia Islands (1), in the vicinity of the enemy air base at Munda, and engaged the Japanese. The inset shows this area in detail. To the west, the Allies occupied Woodlark Island (2) and the Trobriand Islands (3) without opposition. In New Guinea they occupied Nassau Bay (4), just below Salamaua; the landing craft encountered only slight resistance. Apparently these widespread operations have as their ultimate goal the reduction of Rabaul (5), which was bombed.

The big bombers, which have punished Rabaul extensively in recent weeks, ran into heavy Japanese anti-aircraft fire and interference from some enemy night fighters. One American bomber was missing after the raid.

The Tobriand and Woodlark islands will be valuable as stepping-stones in a chain of fighter-plane bases from the Allied stronghold of Milne Bay, on the tip of New Guinea. Japanese-held Gasmata and Rabaul may be raided with comparative ease with the aid of these bays.

NAVY GIVES FIRST NEWS

The first report of landing actions came early yesterday when the Navy announced here in a communiqué that combined United States forces had landed June 30 (Solomons time) on Rendova Island, in the New Georgia group, which is only five miles from the important Japanese air base of Munda, on New Georgia Island, but that communiqué said, “No details have been received.”

A hint that the fighting had extended came later from Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox in Los Angeles, where he is inspecting Pacific Coast installations. The Secretary declared that the Rendov attack was the beginning of “an offensive against the Japanese base at Munda and surrounding bases.” Navy officials in Washington yesterday declined, however, to confirm that the attack had been extended to New Georgia.

General MacArthur’s announcement of more sweeping actions in the Pacific seemed to confirm impressions that the American forces were running into opposition on Rendova and were not making a bloodless conquest as had been the case in the occupations of Funafuti, in the Ellice group, and in the Russell Islands, northwest of Guadalcanal, which were the last two places in the South Pacific revealed by the Navy as occupied by our forces.

On March 27 American planes bombed and strafed Japanese positions at Ugali, which is on the northeast coast of Rendova, a previous Navy communiqué disclosed. This indicated that there were enemy forces on the island, which, if they still were there, undoubtedly were resisting.

Observers here have been expecting action in the South and Southwest Pacific for some time. Attention, however, had been focused on spots other than obscure Rendova, a twenty-mile-long, densely wooded island, 195 air miles northwest of Guadalcanal.

Munda was for a while the “Japanese Malta” of the central Solomons. It has been bombed at least 150 times since last November, and the attack on Rendova was preceded by four bombings of Munda within four days. For a brief period a few months back our South Pacific fliers let Munda alone and the impression arose that it had been knocked out by the severe punishment it had received. Then, apparently, the Japanese put it in commission, for the poundings were resumed.

It is believed that American strategy, now that the southern Solomons are safely consolidated, is to move northward through the central Solomons, up to the northern Solomons, where the Japanese are believed to have heavy troop concentrations, and then, if things go well, to the more important objective westward and northward.

It is regarded as entirely likely that the immediate objectives, if Munda is knocked out, are Bougainville Island, about 155 air miles to the northwest, where the important harbor and air base of Kahili is situated, and Rabaul, on New Britain Island, one of Japan’s strongest air and sea bases in the southwest Pacific.

Rendova in American hands will give our forces a base 195 miles nearer Japanese targets than Guadalcanal. Rendova is 103 miles from Rekata Bay, submarine and seaplane base; only twenty-five miles from Vila, an air base; 137 miles from bases in the Shortland area, and 410 miles from Rabaul.

Rendova is described by the Navy as “entirely mountainous and densely wooded.” It gradually increases in height from its southeastern extremity, where it is 1,021 feet high, to its summit, a precipitous volcanic cone called Rendova Peak, which is 3,488 feet high. This peak, only four miles from the northern end of the island, has been a conspicuous landmark in air flights over the island. Its summit, an extinct crater, is frequently obscured by clouds.

There is a black sand beach called Banyetta Point at the western extremity of the island. Tidal currents there are strong. The coast rises steeply and is thickly wooded.

From seven miles above Banyetta Point to the northern point of the island, a barrier reef parallels the coast. It extends out a maximum distance of two and one-half miles. There are six deep passages through the reef, and several islands are located on the northern part of the reef. The lagoon inside the barrier is shallow and is encumbered by several reefs

JULY 6, 1943

PUBLISHER VISITS KREMLIN

Sulzberger and Molotoff Confer For an Hour In Moscow

MOSCOW, July 5 (AP) —Arthur Hays Sulzberger, president and publisher of The New York Times, spent an hour today in the Kremlin with Foreign Commissar Vyacheslaff M. Molotoff.

Mr. Sulzberger said later he could disclose no details of the interview. He was introduced to Mr. Molotoff by William H. Standley, United States Ambassador.

The publisher has been here as a special Red Cross representative and expects to leave Moscow within a few days.

JULY 11, 1943

Eisenhower Rubs His Seven Luck-Pieces As Allied Invasion Fleet Approaches Sicily

By EDWARD GILLING

Representing the Combined British Press.

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, July 10 —Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower always carries in his pocket seven old coins, including a gold five-guinea piece.

As the Allied invasion fleet approached Sicily last night to begin the great assault on Europe, the General gave them a good rub for luck. In fact, as one of his aides said, he gave them several good rubs.

In the early hours of the morning the General heard that the landing had been made and that everything was going according to plan. General Eisenhower spent all night at headquarters, except for one brief period when he drove out to the coast with a small party of his staff to watch an Allied air fleet leaving.

Climbing out of his car, he stood in moonlight with his hand raised to salute the air armada. The period of waiting between the planning of the assault and its realization was over.

Returning to headquarters, General Eisenhower went at once to the naval section, where he joined his staff in following closely the movement of the operations on charts. He spent some time in the Fighter Command room, from which the air umbrella covering the operations was controlled.

At 1:30 A.M. General Eisenhower, apparently satisfied with the progress of operations, went to bed on a cot in a room next to the war room. He slept soundly for three hours until awakened at 4:30 A.M. by an aide who informed him that assault troops had landed and that everything was going according to plan.

The Royal Navy served the General a cup of hot tea and he then returned to the war room, where reports were now coming in regularly. He remained there until he heard the British Broadcasting Corporation broadcast his message telling the people of France that this was the first stage of the invasion of the Continent, which would be followed by others.

General Eisenhower then left the war room, but only for a change of clothes. He returned soon to follow with his commanders the progress of operations.

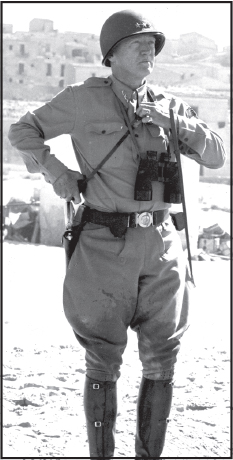

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander in chief of Allied Armies in North Africa, and General Honoré Giraud, commanding the French forces, saluting the flags of both nations at Allied headquarters, 1943.

JULY 11, 1943

ROOSEVELT SEES ‘BEGINNING OF END’

President Reassures Pope on Sparing of Churches and on Respect for the Vatican

By BERTRAM D. HULEN

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, July 10 —The Allied invasion of Sicily looks to President Roosevelt like “the beginning of the end” for Adolf Hitler and Premier Mussolini.

This was revealed by the White House today as an intimation was given that success in Sicily would be followed by the invasion of Southern Italy.

President Roosevelt stated his views in a dramatic announcement when he received word of the invasion during a dinner at the White House last night in honor of Gen. Henri-Honoré Giraud, the French Commander in Chief.

The intimation that Southern Italy might be the next objective was contained in a communication given out by the White House today from President Roosevelt to Pope Pius XII.

In it the President promised that during the invasion of Italian soil churches and religious institutions would “be spared the devastations of war” and the neutral status of Vatican City, as well as of Papal domains “throughout Italy,” would be respected. Mr. Roosevelt assured the Pontiff that the United States was seeking “a just and enduring peace on earth.”

Mr. Roosevelt’s views concerning the campaign in Sicily were echoed at noon by Senator Tom Connally, Democrat, of Texas, chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, who discussed it with the Chief Executive when he called to say good-bye before leaving for Texas.

Our forces will sweep through Sicily,” the Senator declared as he was leaving the White House. “Already on the land, I don’t believe they can be stopped. The curfew has rung for Italy.”

Nevertheless, there was an air of caution here today until the fighting had developed further, because of reports that the Axis has concentrated in Sicily 300,000 troops, including at least two German divisions. The rest are Italians.

The Allied forces consist of British, Canadian and American units. The Americans, from indications given by military experts, are grouped in the Fifth Army under the immediate command of Lieut. Gen. Mark. W. Clark, with Gen. Dwight D. Elsenhower in over-all command from North African headquarters. The British and Canadians are reported probably to outnumber the Americans.

It is considered probable that some days may elapse before definite conclusions can be reached concerning the progress of the campaign, but it is clear that Allied success would mean air and sea control of the Mediterranean and open the way for the conquest of Southern Italy, Sardinia and other Mediterranean points.

Although the operation is not a second front in Europe, it could open a way for such an undertaking.

These considerations were apparently in the mind of President Roosevelt when he made his dramatic announcement at the dinner last night. The details were revealed by Stephen F. Early, Presidential Secretary, today.

The guests included Secretary of State Cordell Hull, Gen. George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff; Admiral William D. Leahy, the President’s Chief of Staff; Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet, and other military and naval officials.

ANNOUNCES NEWS OF ATTACK

President Roosevelt began receiving reports of the invasion of Sicily at about 9 o’clock. Just before 10 o’clock, as the dinner was nearing its close, he made the dramatic announcement:

“I have just had word of the first attack against the soft underbelly of Europe.”

He then asked the guests to say nothing about it until midnight, when simultaneous announcements would be made in North Africa, London and Washington.

He stressed that the major objective was the elimination of Germany, for once ashore our forces could go in different directions, that it certainly was to be hoped that the operation was the beginning of the end, and it could almost be said that it was.

In a toast to unified France, he promised that while this invasion was not directed at the shores of France, eventually all of France would be liberated.

After telling of the attack and landing, the President said:

“This is a good illustration of the fact of planning, not the desire for planning, but the fact of planning. With the commencing of the expedition in North Africa, with the complete cooperation between the British and ourselves, that was followed by complete cooperation with the French in North Africa.

“The result, after landing, was the battle of Tunis. That was not all planning; that was cooperation and from that time on we have been working in complete harmony.

“There are a great many objectives, of course, and the major objective is the elimination of Germany. That goes without saying, as a result of the step which is in progress at this moment. We hope it is the beginning of the end.

“Last autumn the Prime Minister of England called it ‘the end of the beginning.’ I think we can almost say that this action tonight is the beginning of the end.

“We are going to be ashore in a naval sense—air sense—military. Once there, we have the opportunity of going in different directions and I want to tell General Giraud that we haven’t forgotten that France is one of the directions. One of our prime aims, of course, is the restoration of the people of France and the sovereignty of France.

PLEDGES LIBERATION OF PARIS

“Even if a move is not directed at this moment at France itself, General Giraud can rest assured that the ultimate objective—we will do it the best way—is to liberate the people of France, not merely those in the southern part of France, but the people in northern France—Paris. And in this whole operation, I should say rightly in the enormous planning, we have had the complete cooperation of the French military and naval forces in North Africa.

“Gradually the opposition has cooled. The older regime is breaking down. We have seen what has happened or is happening at the present moment in Martinique and Guadeloupe. That is a very major part toward the big objective.

“We want to help rearm those French forces (the President referred to the French forces in North Africa) and to build up the French strength so that when the time comes from a military point of view when we get into France itself and throw the Germans out there will be a French Army and French ships working with the British and ourselves.

“It’s a very great symbol that General Giraud is here tonight, that he has come over to talk to us about his military problems and to help toward the same objective that all of the United Nations have—freedom of France and with it the unity of France.”

GIRAUD THANKS ROOSEVELT

General Giraud, in responding, thanked the President for the support being given France and expressed gratification for American assistance in rearming the soldiers of France.

He then raised his glass in a toast to the President and “the glory of the United States,” referring to this country as “that great nation through which peace and freedom will be restored to the world.”

JULY 11, 1943

GIRAUD’S VISIT REVIVES CONTROVERSY

Americans Caught Up In Emotional Storm That Has Swept Over Frenchmen—President Disappoints Both Sides

By HAROLD CALLENDER

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, July 10 —The visit to Washington this week of General Henri-Honoré Giraud, who is commander of the French forces in North and West Africa and shares with General Charles de Gaulle the chairmanship of the new French Committee of National Liberation at Algiers, has revived the impassioned controversy that has raged around those two men and the situation in North Africa for six months.

It has raged in North Africa, in London and in Washington, with echoes in remoter places like Moscow and Tahiti and New Caledonia. Although Algiers has not been’ silent—it never is—the storm center this week has been Washington.

At a huge reception for General Giraud yesterday the ballroom of one of the largest Washington hotels glittered with French, British and American uniforms. In that room this correspondent listened to a de Gaullist who felt sure the United States had ruined its reputation in Europe by interfering in French affairs so far as to insist that General Giraud be retained as French commander.

CLASHING OPINIONS

A few feet away he met a Giraudist who warmly praised the official American policy and said the de Gaullists were about as important as their armed forces in North Africa, which numbered 11,000 in a total French force of about 70,000.

Both de Gaullists and Giraudists expressed consternation at the remark made earlier that day by President Roosevelt to the effect that the French were under Germany’s heel and therefore there was no France now.

What, undoubtedly, Mr. Roosevelt meant was that there was no French State to speak for France. If he had said that, his words would have caused less astonishment, but perhaps not much less disappointment; for Frenchmen of both groups have hoped the committee at Algiers would be recognized by the Allies as the ad interim French authority that might speak for France in Allied councils and hold as trustee for France all available territories, including Martinique.

Americans too have been drawn into the emotional torrent. There are Americans sitting at desks in Washington who lose their tempers at the mere mention of de Gaulle or Giraud. Some who were ardent for General de Gaulle have gone to North Africa and come back ardent for General Giraud, or vice versa.

Correspondents here who think it their duty to tell their readers of the official coolness toward General de Gaulle and why it exists are swamped with letters denouncing them for maligning General de Gaulle.

There is something about this controversy that upsets the emotional and perhaps the intellectual equilibrium not only of Frenchmen but of Americans and Britons. It is certainly not the quiet, composed, gentle personality of General Giraud, whose only or at least whose main desire seems to be to kill Germans in a systematic, professional and mechanically efficient manner so as to liberate France and restore French institutions, including, no doubt, the right of Frenchmen to quarrel endlessly among themselves as they have traditionally done.

EMOTION UNLEASHED

General Giraud’s appearance in Washington happened to unleash a new flood of emotion because it was a logical occasion for defining what our officials would describe as the de Gaulle problem and the present attitude of the principal Allies toward it.

The emotionally provocative qualities of the controversy derive from two assumptions on the part of the de Gaullists and the reactions to those assumptions in other quarters.

The first assumption is that General de Gaulle or his movement represents the French people in a special sense—the “petits gens” or little fellows or forgotten men who work hard for a living and have no family estates or distinguished ancestors—the masses who live what may be called the left side of the line of demarcation that has run through the French nation without much variation since the Revolution of 1789.

According to this view Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain and his circle sinned not only by too readily accepting defeat and collaboration, but principally by being politically and socially reactionary—by representing those who never accepted the French Revolution; and de Gaullism is therefore depicted as the youthful, progressive, democratic side of France.

DYNAMIC NATIONALISM

The second assumption is that de Gaullism embodies a dynamic French nationalism indispensable to the revival of a ravaged nation, a nationalism the arteries of which have not begun to harden.

It is a ruthless nationalism calling for purges on all sides and even whisperings of guillotines. It is directed not only against the Germans but just now also against the Allies, who are accused of unnecessarily infringing French sovereignty by taking possession of ports and communications in North Africa and by dictating who shall command the French forces.

It probably will be directed in the future against all foreigners and may verge upon xenophobia, as nationalism in its extreme forms usually does.

Meanwhile, in less friendly quarters the first assumption mentioned above was flatly rejected on the ground that none could tell who, if anyone, represented the imprisoned French people of today. Some frankly feared that General de Gaulle and his underground Allies within France might turn out to be communistic. Had not a Communist Deputy joined General de Gaulle in London? In the same quarters the second assumption was angrily denounced as calculated to interfere with the military operations of the Allies, since it was accompanied by a demand for a purge of French Army officers that our military authorities thought would impair the efficiency of a force which had fought extremely well against the Germans.

ALLIED RESPONSIBILITY

Moreover, it was regarded as absurd for Frenchmen to squabble over technicalities of sovereignty at a moment when Allied armies were preparing to liberate France, whose sovereignty could not be said to exist unless those Allied armies won the war. The Allies had a right to determine how the French could best cooperate in that common task, since the Allies were bearing the major burden and expense and were responsible for the high command.

The two assumptions apparently have generated in General de Gaulle supreme confidence in his popularity and his destiny and a sense of having a kind of Joan of Arc mission to save France. All men with missions tend to inspire boredom or distrust or both in those who do not share their enthusiasm; and de Gaulle, by frankly expressing his aspirations, seems to have put some people’s backs up, notably at the conference at Casablanca.

Moreover, General de Gaulle for three years has carried on a campaign that necessarily clashed all along the line with American policy. For he was denouncing as unworthy and traitorous the government of defeat which the United States recognized and dealt with—although with constant misgivings—as the government of France. It therefore seemed to Washington that de Gaulle’s mission was to frustrate our policy; and for that there was no quick forgiveness.

The recognition of the Vichy Government is now gone, but General de Gaulle is still sabotaging our policy, this time our military policy which alone can save France—so it seems to Washington officials. If he wants to dispel distrust, why does he not stop arguing and start fighting Germans, since he is a military man, ask his critics.

OUR INTERVENTION

American emotions are stirred mainly by the first assumption—that de Gaullism is democracy and all that opposes it is toryism. Prime Minister Churchill’s acceptance of what is described as an antide Gaullist policy is explained by recalling that he is a Tory. President Roosevelt’s adoption of the same attitude is not so easy to explain, but the critics attribute it to some of his advisers in North Africa and here.

From Algiers this week comes the report that many Americans object to Allied intervention in French affairs “to frustrate de Gaulle.” Others think it would be more logical to object to intervention as such, whomever it might frustrate.

The invitation to General Giraud to come here was interpreted as designed to increase his prestige not only with the Army but with civilians in North Africa. His visit is now officially described as strictly military, although it would be rash to suggest that in the General’s conversations here no mention will be made of the committee that aspires to rule the French Empire and its armed forces.

UNITY STILL ABSENT

The status of that committee remains obscure pending definition of the Allied attitude toward it. The case of Martinique, where the Vichy regime has collapsed, offers the opportunity for such a definition.

Meanwhile, the extent of de Gaulle’s influence in the committee and in the French Empire, and the somewhat unbending nature of de Gaulle, seem to preclude at least for the present that French unity which everybody has professed to desire.

FOURTH-TERM RACE TAKEN FOR GRANTED

But Recent Washington Rows Suggest Re-election Is Far From Certain

POLITICAL TACTICS SHAPED

By TURNER CATLEDGE

WASHINGTON, July 10 —Regardless of the political strain which the intramural feuding and clashes between the White House and Congress undoubtedly have imposed lately upon the Administration, the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt for a fourth term as President is still taken for granted here.

Reports from the country as to reactions to the continuing squabbling in Washington suggest the advisability of a recheck by those who would make Mr. Roosevelt a heavy-odds favorite for re-election against the entire field, Democratic and Republican. There appears no evidence that he will be seriously countered in his own party, but a general disgust with the Washington rows, as reported, especially from the Middle West, may, if the quarrels continue, bring about a tightening up of the winter book quotations for 1944.

SIGNS OF WANING SUPPORT

Regardless of the belief that Mr. Roosevelt will be nominated again—assuming, of course, that he wants to be—he perhaps will have less emotional support than ever before from the rank and file of the heterogeneous aggregation that has occupied the Democratic wigwam for these last ten years.

Ardor for him has cooled and is cooling perceptibly among his partisans in some regions. Feeling has run pretty deeply in the South over the activities of the Administration, and particularly of Mrs. Roosevelt, in relation to the delicate racial problem, and in the Middle West over efforts to control farm prices.

Realizing all of this, the White House political high command headed by Harry Hopkins, with David K. Niles as first assistant, is not expected to try to give the fourth-term nomination the semblance of a “draft,” as they did the third-term nomination in 1940. They are expected, on the other hand, and in their own time, to go after the plum by direct and obvious means, always with this legitimate question: “Pray, who else?” And, if the fighting is still under way in the fall of 1944, they can be expected to present the case of Mr. Roosevelt’s fourth-term election as a military necessity to assure victory for the United Nations, and as a means for insuring a more lasting peace for the whole world.

PREPARATORY STEPS

The fourth-term planners are letting no grass grow under their feet. The recent appointment of George E. Allen as secretary of the National Committee can be considered as in line with the purpose of the planners to become more active, especially in appeasing the virulent opposition within the party. Mr. Allen is what is known in his native Mississippi as “a smooth operator.”