Chapter 16

“RUSSIA STILL ASKS FOR SECOND FRONT”

August–September 1943

T he popular interest in the Italian campaign continued to dwarf all other news. American and British forces were winning there while news from the Russian Front and the Pacific was patchy and unclear. On August 17 the conquest of Sicily was over, though one-third of Axis forces managed to escape across the Straits of Messina before the Allied trap could be closed. There were around 20,000 Allied casualties while the Axis lost 160,000, most of them Italian soldiers only too willing to be captured. The Allies pursued what seemed to be a beaten enemy onto mainland Italy, their first steps on European soil. The new government in Rome, led by Marshal Pietro Badoglio, kept fighting out of fear of what the Germans might do if Italy surrendered. Within weeks of Mussolini’s fall in late July, the number of German divisions in Italy increased from six to eighteen. Continuous bombing forced Badoglio’s hand and on September 3 an armistice was signed.

Montgomery began to move his army to Calabria and on September 9, the day after the armistice was formally announced, General Mark Clark led a combined Anglo-American force to storm the beaches at Salerno, in the Bay of Naples. The landing was strongly opposed by a German Army now occupying its former ally’s territory. Mussolini was rescued from prison by a unit of German commandos and an Italian social republic was declared at the northern Italian city of Salò, establishing what The Times called a “New Kind of Regime.” The fight for Salerno was the toughest so far, but by September 20 the German counterattack had been repulsed. The German Army retreated to a line north of Naples, after first wrecking the port. The city was liberated on October 1.

The invasion of Italy, even more than the invasion of North Africa, posed complicated challenges for American diplomacy. “It was a test,” wrote Times correspondent Harold Callender, “of our ability to comprehend as well as to liberate Europe.” From Washington it was difficult to grasp European realities. The long arguments about whether to support de Gaulle or Giraud continued to take up column inches in The Times. On August 27 Roosevelt finally made a halfhearted gesture by agreeing to recognize the French Committee of National Liberation, dominated by de Gaulle, as representative of French overseas territory, but not as a potential government for France. The situation in Italy was also complex, since Badoglio was a former supporter of Fascism and the king, Victor Emanuel III, was widely unpopular. No commitments were made this time to the conquered regime, but with Rome still in German hands it was hard to come up with an alternative.

The Times took a strong stand on the need to ensure that America would play its part in restructuring world politics after the war. In an editorial on September 14 The Times reminded readers that “this time the United States intends to help enforce a world peace when it is won.” This was easier said than done, and there was a long road ahead before peace could be certain. Stalin in Moscow repeated his demands for a second front in Europe to take the pressure off Russian armies. The Soviet leadership regarded the Italian campaign as a sideshow, as did many Americans. By this time the Red Army had consolidated its victory in the summer at Kursk and pushed the German Army back on every front. Smolensk was liberated on September 25 and bridgeheads were made over the Dnieper River toward the city of Kiev. On September 26 The Times ran another article by the famous Soviet correspondent, Ilya Ehrenburg, who had popularized the propaganda of hate against the Fascist enemy in 1942 and 1943. In “Hate Marches with the Red Army” Ehrenburg explained that a war like this “plows up men’s souls.”

PLOESTI SMASHED

300 Tons Rain On Major Gasoline Source of Reich Air Force

RAID MADE AT LOW LEVEL

Delayed-Action Bombs Enable 2,000 Fliers to Get Away, Leaving Great Fires

By A. C. SEDGWICK

By Cable to The New York Times.

CAIRO, Egypt, Aug. 1 —A day-light air attack that “may materially affect the course of the war” smashed the oil refineries and dependent installations at Ploesti, Rumania, where fully one-third of the Axis’ petroleum supplies for use in aircraft, tanks, transport vehicles, submarines and surface hips is believed to originate.

[The area produces 90 per cent of the German Air Force’s gasoline, according to The United Press. The distance flown by its attackers was believed to have set a record for aerial warfare.]

The raiders, numbering more than 175, were all Liberators of the Ninth United States Air Force. The 2,000 men in their crews had been trained especially for this all-important mission and the machines were equipped with special low-altitude bomb-sights.

300 TONS OF BOMBS DROPPED

The planes were over their target at about 3 P.M. today. They remained not more than a minute and then were off, having dropped their great load of bombs with what, judging by first reports, seemed to have been highly satisfactory results. The pilots reported that, according to every indication, many fires and explosions had been caused. In all, some 300 tons of high-explosive bombs, mostly of the delayed-action type, were dropped. Clusters of incendiaries by the hundreds were also dropped, all from altitudes of less than 500 feet.

Brig. Gen. U. G. Ent led the formations. His plane was among the first to return. All the aircraft had been expected about an hour earlier and there had been a period of the greatest tension. Lieut. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, American Commander in the Middle East, was among the anxious crowd. He was the first to welcome General Ent and to hear reports from a number of officers.

Col. Keith Cropton said “We got them completely by surprise.” Capt. Harold A. Wickland, who also took part in the recent Rome raid, said: “I saw a lot of smoke and we did some damage, but it all happened so quickly I don’t know what it was we hit.” Many others gave testimony that tended to show the general impression that widespread damage had been done.

RUMANIANS SEEM FRIENDLY

Particularly interesting at this time was the testimony of several of the air crews. They said that the Rumanian peasantry had shown the greatest friendliness. Rumanian girls were said to have waved “a great welcome.” A Rumanian soldier, gun on shoulder, was described as completely unconcerned.

It was said at Ninth Air Force headquarters that months of planning and preparation had gone into this attack on Ploesti. Not only military specialists but authorities on oil refining were consulted.

It was explained that, for several reasons, no large-scale bombing of the Ploesti refineries had been attempted before. The nature of the target makes it particularly invulnerable to attack by small formations.

Oil storage tanks at the Columbia Aquila refinery in Ploesti, burning after the raid of American B-24 Liberator bombers, 1943.

There were too few long-range heavy bombers based within striking distance of Ploesti. The distance to the target from any Allied airdromes rendered it impossible to attack with large forces of medium bombers.

As soon as it appeared feasible to the Allied commanders to destroy Ploesti, a plan for doing so was formulated and its execution fell to General Brereton, the first commander of heavy bombers in the United States Army Air Forces to see action in this war. General Brereton supervised all phases of training and practice for the raid.

Repeated high-level attacks on Ploesti would undoubtedly have accomplished its destruction, but such a process would have meant heavy losses to the attacking force. It would also have enabled the enemy to protect his installations.

EXTREMELY VITAL TARGET

The city of Ploesti, with its adjoining oil fields, refineries and transportation facilities, is generally conceded to be one of the most vital targets in Europe. Perhaps as much as half the entire German war machine would be halted if it were obliterated.

In 1941 the Russians realized its importance but were unable, in two raids, to do more than a modicum of damage. In June, 1942, a small force of Ninth Air Force Liberators attacked but had little success, largely because of foul weather.

Ploesti and its vicinity have thirteen refineries, seven of which are said to produce almost 90 per cent of all Rumania’s oil. The rest are all small and some are obsolescent. The Ploesti refineries can produce annually approximately 11,500,000 tons, but, since the German occupation, the flow of crude oil from the ground has dropped to a point at which it can supply scarcely more than half the capacity of the refineries.

Nevertheless, it is estimated that the Ploesti area still supplies at least 35 per cent of Germany’s petroleum demands, including, besides aviation fuel, ordinary gasoline for motor transport and lubrication and Diesel oils. Including its refineries and pump stations, which encircle the city, the Ploesti area approximates nineteen square miles. Most of it is an enormous rail ganglion.

AUGUST 4, 1943

AXIS POSITION IN SICILY GROWS MORE PERILOUS

Americans Sweep Past Troina—Canadians Take Regalbuto

EIGHTH ARMY FLANK GAINS

Catania Now Faces Multiple Drive as Ships and Planes Help Land Advance

By MILTON BRACKER

By Wireless to The New York Times.

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS, NORTH AFRICA, Aug. 3 —Converging inexorably on Mount Etna and northeastern Sicily, the Allied forces have battered down increasingly stubborn opposition to capture Regalbuto, Centuripe and Troina.

While the Canadians smashed their way into Regalbuto and the British Seventy-eighth Division took Centuripe, the Americans continued eastward from the Nicosia-Mistretta road line to sweep beyond Troina, the last German bastion directly west of the inner ring around Mount Etna. With the offensive mounting in power and the bases ahead, as well as ports in Italy, undergoing constant aerial pounding, the Allies now appear to be thrusting out one steel prong north of Mount Etna, possibly by way of Randazzo, while the other cuts its way forward toward Catania.

[Some American units are reported to be less than twenty miles from Randazzo, the British radio said, according to the Columbia Broadcasting System.]

MULTIPLE DRIVE ON CATANIA

The drive against Catania is a multiple offensive in itself. British Eighth Army artillery is hammering the German positions along the coast, while the captors of Regalbuto and Centuripe clearly menace the city from the rear, via Paterno. Within twenty miles of Regalbuto and fifteen miles of Centuripe, Paterno would be the last obstacle confronting the Army sweeping down on Catania from the northwest. Besides Paterno, the Allies threaten Adrano, from which Catania could be cut off or reached via Biancavilla and Belpasso.

[The Allies were within six miles of Adrano, The United Press said.] The advance has averaged about ten miles on a broad front. The situation is bound to be uncomfortable for the reformed Hermann Goering Division and the German paratroopers around Catania. To the right of the British Seventy-eighth Division—veterans of the entry into Tunis—the Fifty-first Highland Division is forging its way ahead against opposition that includes the Twenty-sixth Italian Division—apparently the only major Italian unit still battling for Sicily—and the German Fifteenth Armored Division.

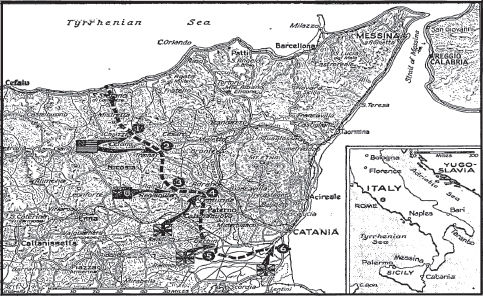

American advances that overran Capizzi (1) and, to the southeast, Cerami and Troina (2) threatened to throw a ring around the enemy’s Mount Etna positions. These positions were further jeopardized when the Canadians broke through to Regalbuto (3) and units and units of the British Eight Army smashed forward to Catenanuova and Centruripe (4). In addition, British troops above Rammacca entered the western end of the Catania Plain (5) and kept up their pressure near the city of Catania itself (6) with heavy Eight army artillery bombardments.

TWO NORTHERN TOWNS TAKEN

In the north, the Americans’ success around Troina was preceded two days ago by the capture of Capizzi and Cerami. The fall of the two towns had previously been announced, but their names were made public only today. The Americans have been progressing against the German Twenty-ninth Motorized Division.

[The Germans were trying to establish a temporary anchor at San Fratello, The Associated Press said, but the occupation of the Troina area would make San Fratello strategically untenable.

[Off both the north and east coasts, The Associated Press added, warships continually swept behind the enemy front to batter rear communications and troop movements.] The Axis troops face the weight of extensive Allied reinforcements brought up during the period of apparent inactivity before the opening of the great new drive on Sunday. Although the enemy resistance has continued to stiffen as the means of escape narrows, the Germans in particular have paid a heavy toll.

But the Allies have recently had to fight over some of the most difficult terrain imaginable. Guns and tanks have been doing their share, but basically it has been an infantry job.

Before the announcement of the fall of Regalbuto, Centuripe and Troina, the communiqué issued here filled in the details of previous operations. The advance on the plain of Catania continued generally north and northeast from Rammacca and Raddusa. These towns formed the lower corners of an irregular oblong, with Regalbuto and Paterno at its upper ends.

At the same time a substantial bridgehead was established north of the Dittaino River in the vicinity of a captured town that has not been identified. After a laborious advance through rocky country other British and Canadian troops gained positions overlooking Agira, west of Regalbuto, and now plainly behind the lines. [The Eighth Army has captured Catenanuova, Reuter reported.]

PLANES COOPERATE CLOSELY

Operating with the ground forces, Bostons, Mitchells and Baltimores of the Northwest African Air Forces concentrated on Adrano, Randazzo, Milazzo and Messina in Sicily and on Reggio Calabria in Italy. Fighters cotinued their sweeps and patrols over the island.

In other operations, Beaufighters strafed a destroyer and three motor torpedo boats off Cagliari, Sardinia. Lightnings shot down three enemy aircraft and damaged two while assisting flying boats in an air-sea rescue.

Naples was attacked for the second successive night. [“Block-busters” and incendiaries were dropped in railway areas, The Associated Press said.] During all these operations, seven Allied craft were lost.

AUGUST 6, 1943

FLAME THROWERS DECISIVE

Account for Many Pillboxes In Final Drive on Munda

By GEORGE JONES

United Press Staff Correspondent.

MUNDA AIRPORT, New Georgia Island, Aug. 3 (Delayed) —The battle for Munda airfield virtually ended today, except for mopping up, when sweat-stained American jungle troops poured onto this strategic airstrip, an objective toward which they had struggled yard by yard for thirty-five days.

For the past three days the Japanese defenses have cracked wide open. It is believed now that they began evacuating high-ranking officers and some troops by destroyer to Kolombangara Island to the northeast several days ago, leaving a rear guard to protect the evacuation.

These battered Japanese were instructed to “fight to the death” for their Emperor. They are still hurling a weak challenge from Kokengolo Hill extending from the airport in a northwesterly direction.

American artillery, which has tormented the Japanese since the start of the campaign, poured hundreds of shells on this position in preparation for the final extermination of the enemy remnants.

Other American troops moved north, attempting to cut off the would-be evacuees. Small craft last night sank a small Japanese ship in narrow Blackett Strait and damaged two barges in early stages of the Japanese flight from New Georgia.

The writer has just visited the airport, where he surveyed the ravaged face of Munda. Americans and Japanese were exchanging mortar and rifle fire across the western edge of the airstrip. Half a dozen enemy Zeros and Mitsubishi two-motored bombers were scattered about the revetments. Souvenir hunters already had started stripping them.

The United States forces were now inside the airport at the eastern edge and along the field on the east and south boundaries. These troops advanced 2,000 yards on Aug. 1 and 2 past battle-scarred Lambeti plantation, along the coast, while in the interior our forces were temporarily held back in their southward advance by remaining Japanese resistance.

The Americans encountered little opposition during the last three days of the advance.

The Japanese evidently were demoralized by the continued artillery and aerial assaults. They left huge stores of rice, damaged field pieces, clothing and blankets.

The Americans easily took the dominating Bibilo Hill, 400 yards northeast of the airport, where it had been anticipated the Japanese would attempt to block our entrance into Munda.

Instead, enemy remnants retreated farther westward behind Kokengolo Hill, where they proved unable to halt our coastal advance into the airport.

TWENTY YARDS FROM THE GOAL

Last night we were twenty yards from our goal. With mortars and one or two 77mm. dual-purpose field pieces of the type fondly called “Pistol Petes,” American artillery was instructed to shell the Japanese.

A few minutes later smoke bombs were dropped on enemy positions. Batteries then began to lay in salvo after salvo of explosives. The barrage lasted all morning.

Pistol Pete was silent this afternoon, his work done.

The airport was in reasonably good shape considering the continuous shellacking it had taken since last December. It shouldn’t be long before the airport is being used by American planes.

This correspondent has examined pillboxes in which the Japanese chose to die rather than surrender. Some were eight feet deep, reinforced with coral and divided into compartments by thick coconut logs. They dotted the hillsides and hilltops.

Only a direct hit could destroy such defenses. Blanket artillery fire and bombings often destroyed the personnel, but the Japanese either replaced casualties or left one machine gunner in each pillbox.

It was in the latter stages of the campaign that we found the answer: flame throwers, which poured in streams of fire and fumes through the apertures of the pillboxes from fifty feet. Flame throwers were credited with destroying thirty-three pillboxes in the past seven days.

Rome Seeks Open City Role; Hitler’s Demands Presented

By DANIEL T. BRIGHAM

By Telephone to The New York Times.

BERNE, Switzerland, Aug. 7 —The Italian Government has begun preliminary operations connected with the declaration of Rome as an open city. The Premier, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, according to travelers from Italy, is taking this measure to prevent Rome from suffering the fate of Warsaw, Rotterdam and Belgrade should Italy become a battlefield.

In this connection the key ministries of defense—War, Navy and Air—have already been removed to other points, while the evacuation of military stores from the capital area is being speeded.

Meanwhile, Italian-German conversations between the Foreign Ministers, Joachim von Ribbentrop for Germany and Raffaele Guariglia for Italy, in Verona, took a new turn late this afternoon when Field Marshal Gen. Wilhelm Keitel, accompanied by many technical experts, arrived by plane from Vienna with Adolf Hitler’s demands for an immediate clarification of the Italian position.

Gen. Vittorio Ambrosio, chief of the Italian General Staff, arrived in Verona last night on the Germans’ invitation to sit in on “important discussions,” which got under way immediately.

While these discussions were extending their scope, the government in Rome demonstrated its internal policy of “pacification” by decreeing a state of war throughout the peninsula, a measure hitherto applied only to the coastline and the Northern Provinces. Believed to be a measure with which to impress the Allies and the Axis, the new move indirectly stiffens the regulation of the martial law decree following the downfall of Benito Mussolini.

Under a state of war decree any civilian “resisting or obstructing the public authority in the performance of its duty” is liable to the death penalty for treason. The Government, therefore, has put teeth into its threats against those who continue in their peace manifestations and strikes throughout the industrial north.

Effective from midnight tonight the new decree comes into force exactly three days before the scheduled completion of the mobilization of all classes born between 1907 and 1922. Both of these measures, the Rome radio said, will “prevent any surprise developments from any quarter that might hinder the Government in its action of conducting the war to an honorable conclusion.”

AUGUST 8, 1943

HARLEM UNREST TRACED TO LONG-STANDING ILLS

Basic Racial Problem Seen Sharpened By New Complaints Born of War

By RUSSELL B. PORTER

Last week’s riot in Harlem, with its toll of five dead, 500 injured, 500 arrested, and an estimated $85,000,000 in property damage, was a social explosion in a powder keg that has been years in the offing.

The Harlem problem is a racial one, rooted in the Negro’s dissatisfaction with his racial status not only in Harlem but all over the country, and exhibited in his efforts, sometimes intelligent and moderate, sometimes blind and extreme, to break down the economic and social discriminations, barriers and frustrations which at times seem unbearable.

In Harlem and other Negro districts where all told 500,000 persons live, there is no question that an ugly mood has existed for some years, especially among the younger Negroes. This condition is not peculiar to New York. As all reports make clear, it is a reflection of a nation-wide attitude—a feeling of resentment and bitterness which came to a head in the depression years and has been nourished by a variety of old and new grievances, many of them real, some fancied or exaggerated, but all being exploited by pressure groups and subversive, anti-democratic elements.

The cleanup after the Harlem riots of 1943.

LONG-STANDING COMPLAINTS

The tinderbox of Harlem was started many years ago when Negro segrega tion and overcrowding gradually transformed much of that historic community into a slum area—a “black ghetto.” These conditions were terribly aggravated in the depression years. Negroes were among the first to lose their jobs. Poverty, misery and crime increased rapidly. Later, when New York became known all over the country for its relief system, new waves of immigrants began arriving from the South, and Harlem became more overcrowded than ever.

The start of the war in Europe brought new problems and accentuated old ones in Harlem. Since Pearl Harbor the principal cause of unrest in Harlem and other Negro communities has been complaint of discrimination and Jim Crow treatment of Negroes in the armed forces, according to responsible Negro leaders. Visits and letters from Negro soldiers and articles in the Negro press keep Harlem continually reminded of the tension in Southern States where Negro troops are stationed.

WAR JOBS A FACTOR

Closely linked to the status of the Negro in the armed services in breeding resentment is that of his status as a worker, particularly in war plants. Not until labor shortages began to threaten war production, Negro leaders say, could Negro workers break down the reluctance of many employers and labor unions to give them jobs in any large number. Even now, they charge, the Negro worker has to contend with many subtle discriminations, especially in upgrading for better jobs.

Students of the problem agree that the most important long-range factor is that of employment, for the refusal to give work to Negroes, or their confinement to menial, low-paid jobs regardless of merit, not only breaks down morale and increases disillusionment but also aggravates the other basic causes to which Negro leaders attribute trouble in Harlem—bad housing conditions, inadequate educational and recreational facilities, substandard health and hospital service, and crime and delinquency.

Much has been done and is being done to improve the situation. After the 1935 riot, the Mayor’s Commission on Conditions in Harlem made a report which was critical of certain aspects of the way the problem had been handled. Although the report was never released, the Mayor has put many of its recommendations into effect. There has been improvement in police methods, housing, health, educational and recreational services. Steps taken against discrimination in civil service examinations have brought more Negroes into the city departments.

OTHER CORRECTIVE STEPS

The City-Wide Citizens’ Committee on Harlem, organized in 1941 with outstanding white and Negro leaders among its officers and directors, has succeeded through cooperation with city officials and private employers, in persuading some large department stores, insurance companies and public utilities to employ Negroes in larger numbers and in better jobs than ever before.

One of the outstanding Negro leaders of the community, Lester B. Granger, executive secretary of the National Urban League, is convinced that much more could be done if there were better leadership among both the whites and Negroes who are actively interested in the problem. He thinks the Negro leadership should return to the more moderate hands in which it was held before 1934 and 1935, when Communists and other extremist advocates of “mass pressure” took over, and that the white leadership should include more practical business men and labor leaders and fewer sentimentalists, professional liberals and the like.

AUGUST 11, 1943

RUSSIA STILL ASKS FOR SECOND FRONT

Sicilian Campaign Considered Fine But Not a Substitute for Major Operation

PESSIMISM IS APPARENT

Many Believe Allies Have the Power To Open Big Drive, Yet Are Not Willing To Do So

By Wireless to The New York Times.

MOSCOW, Aug. 10 —The Russian people do not dispute that the campaign in Sicily is a grand show, but they consider it a small show compared to the military power represented by the combined British Empire and the United States.

It was with some bitterness that a Russian friend said to the writer:

“Of course, our troops would have preferred to take a well-deserved rest after winning the two colossal battles of the Kursk salient and Orel.”

Then he added: “If they are still going ahead, perhaps it is because our high command no longer believes in the early opening of a second front, and we want the war to end soon, anyway. But it would be infinitely easier if a second front were there. Then we really could cut like a knife through butter.

“Today, in addition to the bulk of their land forces, the Germans have every available bomber on this front, That’s why Goebbels had to apologize to the Germans for the German Government’s inability to retaliate against the Allied bombings of Hamburg and the Ruhr, and so on.”

That attitude is fairly typical of the general mood, and it is reflected also in the press. With unconcealed bitterness, Ilya Ehrenburg wrote the other day:

“How soon will the British and Americans move from Italian psychology to the German fortifications?”

There is also some suspicion that, whereas the Allied argument last year that they could not open a large-scale second front was more than plausible, now the Allies “can, but don’t want to.” There also is a tendency to disbelieve the view that the French coastline is impregnable. If we broke through the Orel defenses, why can’t you break through the Atlantic wall? is the attitude.

QUEBEC PLANS LAID FOR RUTHLESS WAR

Military Decisions Covering Germany and Japan Stress Increased Aggressiveness

By P. J. PHILIP

Special to The New York Times.

QUEBEC, Aug. 16 —Until today the Quebec conference has been engaged mainly with the gigantic military and joint operational measures that must and can be taken at this stage toward winning the wars in Europe and the Pacific. All accounts from inside the Chateau Frontenac, where the general staffs have been at work, are that by intense application and goodwill on every side the problems entailed have been largely solved.

The plans for attack and the invasion of enemy and enemy-occupied territory in every war zone have been studied from every angle and a blueprint of the course of the war during the next months—and years, if necessary—has been prepared.

What these plans are will, of course, only become known when they are set in motion. The one thing that can be said about them is that they have been made in a ruthlessly aggressive spirit. What is being sought is the defeat of the enemy in all war zones in the shortest possible time. To that end it is certain that every one of the United Nations will be called upon to fight harder and work harder.

In the discussions of the Chiefs of Staff there have been, of course, no questions of politics. Their job was to plan how to win the war in the shortest time.

POLITICAL ISSUES TO THE FORE

This week the second task of trying to solve the political questions that attach to the military problems must be tackled. A beginning has undoubtedly been made already in the conversations at Hyde Park between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill to which W. L. Mackenzie King, Canadian Prime Minister, also added his quota of council. Before the conference here ends it is expected that Anthony Eden, British Foreign Secretary, will arrive from London,

Like their military chiefs, the political heads of the governments assembled here will have to face their problems realistically. Prejudices and even past policies, it is said, may have to be set aside if sound solutions are to be reached.

The foremost of these problems is how to treat the Italian Government and people. It is now clear that the action of King Victor Emmanuel and Marshal Pietro Badoglio in getting rid of Benito Mussolini and trying to break the fascist regime came too soon. Perhaps some will say that the Allies were not quick enough and powerful enough to take advantage of it.

The German resistance in Sicily has succeeded in gaining time for the application in large part of the plan to which Mussolini gave his assent and to which the King refused his. For all practical purposes the Italian King is as much a prisoner of the Nazis as King Leopold of the Belgians, and the Badoglio government is powerless.

This is a problem that obviously calls for a combination of firm and delicate treatment.

Next, in order of public interest at least, is the question of the recognition of the French National Liberation Committee as the provisional government of France. Here in Quebec and throughout. Canada feeling runs high on this issue, with opinion strongly in favor of immediate recognition as a proof on the part of the Anglo-Saxon powers of their intention to respect their past promises with regard to the entire sovereignty of France and incidentally of all those nations which have been occupied by the enemy.

SUSPICIONS OF IMPERIALISM

It may be said that the publicity given to “AMGOT” has created a suspicion here as well as among some of the governments in exile that the post-war policies of the Anglo-Saxon governments have a flavor of Imperialism that is considered both unwelcome and unbecoming in Allies fighting for the preservation of international as well as national democracy. The third problem on which there is a public demand for clarification is that of the relationship between the Government of the Soviet Union and the other governments engaged in the war.

All these questions of the policy to be followed with regard to Italy, to the French Liberation Committee, to the various governments in exile, and to Russia’s attempts at independent political action are regarded by many here as so closely interlocked that a solution for all of them can be best found in the formulation of a clear statement of joint policy by the governments which are and will be represented here.

AUGUST 17, 1943

CHINA COMMUNISTS FIRM IN DEMANDS

But Chungking Refuses to Give Approval to the Party Or to the Organization’s Armies

CIVIL WAR SEEN UNLIKELY

Some in Government Believe Differences Can Be Removed By Compromises

By BROOKS ATKINSON

By Wireless to The New York Times.

CHUNGKING, China, Aug. 16 —No change is expected in the relations between the central government of China and the Chinese Communists, at least for the present. Although relations are strained, as they have been for years, they seem not to be any better or worse and both sides have many reasons for wanting to avoid violence.

When Gen. Chou En-lai, unofficial liaison officer between the Communists and the central government, started for Yenan, the communist capital, about two months ago with the consent of the central government, many persons hoped that he was carrying information or at least a point of view that would result in a settlement or hold out the promise of a settlement. But by the time he arrived at Sian, the situation had begun to deteriorate.

Now a war of words is going on. From Communist-controlled areas in Shansi and Shensi come bulletins accusing the central government of inefficiency in the war against the Japanese and of preparing to dissolve the Communist party by force. Newspapers in the rest of free China print petitions to Mao Tse-tung and Chu Teh to dissolve the Communist party and turn over the Communist armies to the control of the central government in the interests of a completely united China.

CENTRAL GOVERNMENT’S VIEW

For several years no journalist has been to the region where the Communists are in control so there is no disinterested information on what is going on there but it is easy to discover what the point of view of the central government is. The Ministers and political leaders interviewed in recent weeks agree on one point: There will be no civil war unless the Communists start it.

The Communist representatives here have political and military reasons against civil war. Despite reports of occasional skirmishes all is quiet in the border region with no fundamental change in the political and military situations.

The People’s Political Council and the central executive committee of the Kuomintang, the Government party, are scheduled to meet soon and it will be interesting to see whether they arrive at a decision respecting the Communists.

The differences between the central government and the Communist party are fundamental. The central government cannot tolerate one section of the country that has its own government, army and currency and collects its own taxes. As long as the Communist party remains outside the law of the central government it cannot be recognized as a legal party.

The Communist party asks nothing except recognition as a political party. But it is unwilling to give up its military force on the speculation that the Government and the Kuomintang will accept it as a legal party. It also distrusts certain aspects of the Government.

BOTH LACK UNDERSTANDING

Apart from these fundamental differences, there is a fundamental lack of understanding on both sides which possibly is more serious than the chief points at issue. The minor accusations are bitter.

Some members of the Kuomintang and of the Government think the differences can be resolved by a series of compromises. Since it would be to everyone’s advantage to remove this flaw in national unity, they believe in compromises without violence.

Although the Communist party is not recognized in law, it is recognized in fact. There are seven Communist members of the People’s Political Council. The Chungking Communist party publishes a daily newspaper that can be bought on the street.

To a foreigner who enjoys the paradoxes of Chinese life the only entertaining aspect of the current situation is the presence of Communist headquarters in the former dormitory of the Executive Yuan. On the second floor still live some high officials of the Executive Yuan and near by is the youth hostel of the central government’s political training department.

AUGUST 21, 1943

NAZI SECRET WEAPON DUE

Goebbels Tells Germans It May Halt Allied Raids

LONDON, Aug. 20 (AP) —Dr. Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s propaganda chief, told the German people today a new secret weapon might soon give them relief from Allied air raids.

“The new weapon against the aerial war imposed upon us by the enemy is under construction,” he wrote in his article in the propaganda publication Reich. “Day and night innumerable busy hands are engaged in its completion.”

The text was broadcast by the German radio and recorded by The Associated Press.

American soldiers trudge through muddy ground near the American base at Attu in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, 1943.

AUGUST 22, 1943

Cold, Fog, Mud-Life In the Aleutians

By Foster Hailey

LIFE in the Aleutians in the good old summertime is like this: You crawl out from under the blankets about 7:15—that is, if you want breakfast—hurriedly pull on your heavy underwear, G.I. trousers and close the ventilators. Then you take the rest of your clothes and go into the front room—shut off from the sleeping quarters by a cardboard partition—and complete your dressing there by the little Diesel stove. If you’re finicky about such things you then grab your towel and a bar of soap and head for the washroom, a block away. Careful of that slope there, because the mud is like grease and you’re liable to end up in a slit trench or on top of the quonset at the foot of the slope.

The washroom is warm and steamy from the heat of the Diesel water-heater and the hot water running from ten faucets at which twenty or thirty men are trying to brush their teeth or wash their faces at the same time. You take your turn in line and then gallop back to your quonset to brush your hair and slip on a fur-lined flight jacket or parka.

By this time the sun may be shining, or more probably not shining One thing the sun never does is rise. It just starts coming through the mist or a hole in the clouds, some time during the morning. It never sets, either. There always seems to be fog or clouds in the way. Down south you get so you hate the sight of the sun, a brassy furnace mouth that sears your eyeballs. Up here when it shines you open the door and haul a chair to the lee of a building and bask in it.

The trip to the mess hall, a quarter of a mile away, is a wandering course around mud puddles or through them, if they can’t be avoided. A loblolly of yellow mud six inches thick spreads over the main road. You catch a break in the line of trucks and jeeps and ambulances and dash across. The Lord help you if a truck catches you within twenty feet of the road. You will be spattered from head to foot as it passes.

You pay your 30 cents at the window as you enter the transient Navy mess (luncheon is 40 cents and dinner 50 cents) and sit down on a bench to a breakfast of canned fruit juice, a dish of peaches or apricots or figs, dry cereal with powdered milk (which tastes like chalk, incidentally), eggs and bacon or French toast or hot cakes and coffee. There is plenty of butter and you can have three or four cups of coffee if you like. Luncheon and dinner are in proportion, with fresh salads and dessert and a soup at night. There are no napkins, but, then, what are trouser legs for?

If you are in the Navy or Army you go to work at the change of the watch at 8 o’clock; or, if you have been on duty during the night you go to your quonset and go to bed. If you are a newspaper man you go back to your hut, called the “Press Club” and match quarters for the jeep the Army has furnished and start the rounds of Fighter Command, Bomber Command, Air Force, Island Command, Navy Headquarters; or perhaps you catch the crash boat for a ride out to some ship that has been bombarding Kiska or is just back from the States or Attu.

If there has been a promise of a clear day you won’t have needed an alarm clock. The planes will have been taking off at daylight, seeming almost to scrape the ventilators off the roof of your quonset as they roar over, fighting for altitude to clear the encircling, snow-covered hills.

A visit to the area where Vice Admiral T. C. Kinkaid and Lieut Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner have their headquarters involves a round of dog patting. General Buckner and Maj. Gen. W. O. Butler, commanding general of the Eleventh Air Force, both have springer spaniel pups. Lieut Col. W. J. Verbeck, General Buckner’s intelligence officer, has a magnificent big Irish setter and also is taking care of a retriever for a fellow-officer who is in the hospital. There are many other dogs around the base.

For the men assigned to the base it is a not too uncomfortable life. The temperature generally is in the forties or fifties and everyone has a sufficiency of foul-weather clothing, heavy underwear, wool shirts and trousers, boots, woolen hose, slickers, waterproofed parkas and fur-lined jackets.

The weather is not too bad and probably would go unnoticed in San Francisco. It is the lack of paved roads and sidewalks amid the mud, the long treks to the washroom or the mess hall in the rain that makes it so disagreeable at times. And the lack of sun makes you sympathize with Oscar Wilde’s feeling in “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” when he spoke of “that bit of blue that prisoners call the sky.” A rift in the clouds with the blue sky showing through has everyone pointing and looking and enjoying it

The fliers are really the only ones who see the sun with any regularity. They have a bad time taking off and landing, but once they get “upstairs”—and it often is not far—they have the sun and blue sky above them and below the blanket of fog, white as snow, with the volcanic peaks of the Islands poking through it.

All this, of course, of just one base, but I am told it is very similar all the way along the Aleutian chain. The weather here is not to be confused with that in Alaska, where it is much warmer in the summer and colder in the winter, but where the sun shines more frequently and there are trees and frequent evidences of civilization.

This description of life at this base does not cover, either, the life of the infantry. Nobody loves them. All they do is fight. They bivouac out in the hills, miles from the PX’s and theatres, or on the lonely beaches. They eat from field kitchens and sleep, a lot of the time, in pup tents and on the ground. Occasionally they march in to take a bath or see a movie or go to church, but the buses don’t run to their camp and getting a ride back home often is a difficult assignment. As a result they seldom come to “town,” as the main Army and Navy camps are called.

Does anyone like it? Of course they don’t. But the great majority of them recognize that it is something that has to be done and they want to get along with the doing. Their chief complaint is that it seems to take so long.

I overheard a conversation the other day that seemed to cover the majority attitude. It was two Navy chief petty officers talking. One apparently had just got his orders for some other base or ship.

“Wish you were going back to the States, Joe?” the other asked him.

“No,” he said, “as long as this war is going on I would rather be out here helping fight it. When I go back I want to go back to stay.”

AUGUST 27, 1943

The Roosevelt Statement

WASHINGTON, Aug. 26 (UP) —The text of President Roosevelt’s statement on United States recognition of the French Committee of National Liberation:

The Government of the United States desires again to make clear its purpose of cooperating with all patriotic Frenchmen, looking to the liberation of the French people and French territories from the oppressions of the enemy.

The Government of the United States, accordingly, welcomes the establishment of the French Committee of National Liberation. It is our expectation that the committee will function on the principle of collective responsibility of all its members for the active prosecution of the war.

In view of the paramount importance of the common war effort, the relationship with the French Committee of National Liberation must continue to be subject to the military requirements of the Allied commanders.

The Government of the United States takes note, with sympathy, of the desire of the committee to be regarded as the body qualified to ensure the administration and defense of French interests. The extent to which it may be possible to give effect to this desire must, however, be reserved for consideration in each case as it arises.

LIMITED RECOGNITION

On these understandings the Government of the United States recognizes the French Committee of National Liberation as administering those French overseas territories which acknowledge its authority.

This statement does not constitute recognition of a government of France or of the French Empire by the Government of the United States. It does constitute recognition of the French Committee of National Liberation as functioning within specific limitations during the war. Later on the people of France, in a free and untrammeled manner, will proceed in due course to select their own government and their own officials to administer it.

The Government of the United States welcomes the committee’s expressed determination to continue the common struggle in close cooperation with all the Allies until French soil is freed from its invaders and until victory is complete over all enemy powers.

May the restoration of France come with the utmost speed.

SEPTEMBER 5, 1943

BADOGLIO POLICY MAKES ITALY A BATTLEGROUND

Country Is Invaded After Mussolini’s Successor Tries to Carry On War as Partner of Nazi Germany

BIGGER ORDEAL IS ON THE WAY

By EDWIN L. JAMES

If ever anyone asked for it, Badoglio did. When Mussolini, the bombastic partner of Hitler, went into the limbo as the United Nations were cleaning up in Sicily, the way was open to Italy for the best sort of peace she could get. Badoglio passed up the chance. Whether or not the presence of German troops in Italy influenced his decision is beside the point from a military point of view. He declared he would fight on against the Allies.

Marshal Pietro Badoglio in 1943.

Surely Badoglio knew that the Italian Army could not save his country from defeat. It was apparent that he was counting on German help, and the truth is that he had the evidence of the presence of the Nazis all around him. But that did not change the basic fact that he did not make peace and elected to fight

Now Italy proper has been invaded. And that is but the beginning. It is perfectly plain that Italy is fighting Germany’s war. Hitler has evidently decided to make a battleground of Italy. There he intends to fight a delaying battle against the advancing Allied armies. It is too early to tell to what degree the Italian troops will fight a last-ditch battle, but it is not too soon to say that the battle in Italy is primarily a German battle. Italy has nothing to gain from it; tactically, Germany has a good deal to gain. If she could make the Americans and British fight their way all along from the toe of the Italian boot to the Alps she would perhaps have gained months of delay in any other big attack against her “European Fortress.” Italy is being a sucker for the Nazis.

MISSING A PEACE CHANCE

As the Allies invade Italy proper there is still talk from Italian sources of a “reasonable” peace. These statements are always linked to the statement that the United Nations’ demand for unconditional surrender is impossible because it would be undignified for Italy to accept such terms. Looking over the various emanations from Rome on the subject of peace one finds the idea that the Allies should agree not to occupy Italian soil if Italy should surrender. The Allies could not listen to such a proposition because they intend to use Italian soil and port facilities for the war to beat Hitler. One may imagine that perhaps the chief reason for which the Nazis are planning to defend the north of Italy, where they have sent forces estimated at from fifteen to twenty-five divisions, is to prevent the United Nations from using airfields south of the Alps.

The possession of such fields would bring a large part of southern Germany, including Munich, and a large part of Central Europe, including Vienna, Budapest, Linz and Innsbruck, within easy reach of United Nations bombers. If Italy could obtain a peace which would prevent the use of such airfields and prevent the Italian Adriatic coast from being used for a drive into the Balkans, should the Allies decide on such a campaign, it would spell a German victory of no small importance. Therefore the idea made no headway whatsoever in Washington and London.

Badoglio had a chance to surrender and get his country out of the war. He missed the chance. His country will suffer. The longer he holds on to a forlorn hope, the more his country will suffer.

ONLY A BEGINNING

The landing of Montgomery’s men on the Messina Straits is but the beginning. The Americans have not yet been heard from. In view of the long distance between the toe of the boot and North Italy, it would be no surprise if there were other Allied landings up the coast. Naples has been softened by repeated bombings. The railroads have been crippled.

And in considering the possible strategy of the attackers, it is not to be forgotten that Rome has been declared an open city. That means it is not to be used for military purposes. All of the railroads from the south, with one minor exception, run through the capital. Will the Germans use those roads through Rome? One guesses that the Allies have means of finding out. Furthermore, if Rome is an open city it is not to be defended. This does not mean that the Allies may not occupy it. Under such conditions the capital region looks like a soft spot.

The Germans have made it evident that they will try their big defense in the region of the Po River, running across northern Italy. Their fighting south of that position probably represents a delaying action, and, of course, if the Allies undertake to fight their way all the way up from the Messina Straits to Milan, the Nazis can accomplish a good deal of delay.

THE FIFTH YEAR BEGINS

It is not without interest that as the fifth year of Hitler’s war begins, the Germans are fighting a defensive war everywhere. They are fighting to delay the Russian advance to the east and they are fighting to delay an Allied advance to the south. Even in the war of the air, which they started in their attacks against England, they are on the defensive.

The Germans make it plain that such is the kind of war they intend to fight from now on. One imagines that even Dr. Goebbels has given up hope of conquest in Russia. Germany is driving ahead nowhere; she is now trying to hang on to what she has stolen in the hope that the effort to take it away from her will tire her enemies so that she can keep her frontiers intact and hold on to some of her loot. It is in such an effort that Badoglio is giving aid and assistance to Hitler.

But it will be no fun for Italy and the Italians. The question will surely soon arise as to whether the repressive measures taken by the King and Badoglio will suffice to hold in line all of the Italian people, who must by now realize what sort of a fight they have undertaken. One may imagine that if and when Rome is occupied a crucial situation for Badoglio may arise. And a King in flight loses much of the dignity of his office.

A VERY BIG CAMPAIGN

The Italian campaign is a major undertaking. It is the biggest thing the British and Americans have started in this war. They know they face a formidable foe in the north of Italy. But they have cards to play. Although the Germans in the past three weeks have sent large air forces into Italy, there is every prospect that the United Nations will retain air supremacy during the whole campaign. That is of tremendous import.

Furthermore, the Germans have a bad line of communications. The main support runs through the Brenner Pass, where the railroad and the roads are vulnerable. It is reported that Allied bombers have already wrecked a vital bridge on the railroad. There are many bridges over the mountains and there are many spots where damage to the railroad can be most difficult of repair. The closer the Allies can put airfields, the more attacks can be made on the Brenner Pass.

There are other minor lines for supplies running north of Trieste. But they are not large and are also open to attack from the air and possibly from the land by forces sympathetic with the Allies.

On the other hand, the Allies’ lines of communication are not easy. They are long—running back to the United States and Britain. They are, too, subject to attack. But the large difference exists in the circumstance that the basic sources of supplies for the Allies are much more safe than the German sources.

And, taking into consideration the size of the Italian campaign and its importance, Stalin should realize, and, of course, he does, that it constitutes a great aid to the Russian front. The troops and planes which fight the British and Americans in Italy cannot fight Stalin in Russia.

SEPTEMBER 5, 1943

What About Women After the War?

By Elinor M. Herrick

Director of Personnel and Labor Relations, Todd Shipyards Corporation

I have no idea what the women of America think should be their place in the post-war world. And I am a trifle irked when a “special interest” woman’s group states with what appears to be authority that “American women want this” or that. Too many men, likewise, think they know what is good for women. The truth is that there is no common denominator for women and no spokesman for American women—or for men, either.

Different women want different things. I think most of them—whether they will admit it or not—want only to marry, have a home and children and a man to do their worrying (and sometimes their thinking) for them. Some marry wanting children and can’t have them. Some simply want a life of ease—with a marriage license.

And, of course, there are other women who want Careers—capital C. Others want to be “socially useful.” A lot of women have to earn their living whether they want to or not, either because they have no one to support them or because they are suddenly thrown on their own resources when husbands die or divorce them. A lot of women want homes, children and careers—all three.

So, you see, it’s all very mixed up. The solution won’t be easy. We need a clear-cut social and economic plan. When I say “plan” I certainly don’t mean that we should fall back upon the easy old-fashioned economic solution mouthed so piously after the last World War: “Woman’s place is in the home”; “married teachers must de dismissed”; “no married women hired.” That campaign brought nothing in its train but secret marriages deception and sordidness. It didn’t work. It couldn’t work.

We’ve got to tackle the problem now. Unless some tough-minded thinking is done soon the war will end with women a drug on the market, as they were twenty-five years ago. Any solution will have to cover such basic questions as:

Are we going to plan so that there will be a job for everyone who wants to work? Or only for those who need to work?

Are we going to bar men of independent income from jobs when the war is over? If not, then why should we bar women who don’t need to work but want to?

Are we going to build a system in which everyone must work, produce to justify his existence?

Are we going to say that everyone, regardless of sex, who wants to work must have the opportunity?

What employment conditions will we face when this war ends? There are many more men in the armed services today than at the peak of the last World War, and many more women in industry today than ever before. The Selective Service Act of this war makes it mandatory for employers to re-employ the returning soldier if there is any job at all for him, ejecting employees hired since the soldier left in order to make room for him. This is only fair. Even the temptation to retain women because they are cheaper labor has been largely removed in this war by the government policy of “equal pay for equal work,” and most employers have not even used the loophole in that policy.

Many women who have become accustomed to the independence of having their own money will want to continue in their jobs. Others are already finding the strain of double duty at home and in the factory too hard. Those women who are bored by housework and have found excitement and companionship in the factory will not want to give this up. Some women will want to keep their jobs in order to ease the economic strain until their men, back from the war, find their places. Thousands of soldiers will never return and it is important and only fair that their wives or daughters should have the chance to work.

It is wishful thinking to believe that the majority of America’s newly recruited woman power will flock back into the home. Many will because of their children. Many will not who should. On the other hand, there are already indications that a substantial number of the women war workers will choose voluntarily to give up their jobs. I venture to say that the most frequent reasons for this decision will be that many women left their homes to meet a goal—pay off the mortgage, earn enough for a college education for a child, or buy a new parlor suite or a fur coat. Their objective attained, they quit the job. Many others will undoubtedly leave because they have been unable to maintain proper conditions for their children or have found the physical strain of the combined home and factory job too great.

There will be more unmarried women in the post-war generation. What of them? Will not the increase in their numbers offset the married women who elect to return to their homes? The majority of these single women must work to live. For those who need not work there is plenty of useful, important community service to be rendered, but we have always put the dollar sign as the valuation of work. Volunteer social work will not have much appeal even to those who do not need to earn and who, during these busy war years, have been engaged in exciting war work, driving ambulances or driving generals.

Then there is the vast army of professionally trained women who have been given a place in the sun—at least temporarily. The professionally trained woman has always found it notoriously difficult to secure adequate opportunities in her chosen field and to advance therein. American women have had greater educational opportunities and have used them more widely than the women in any other country. Yet after receiving this expensive education, too often they find themselves frustrated by the professional caste system. And too often they have failed to maintain their sense of perspective and sense of humor. But they have had an uphill fight when there should have been no necessity to fight.

The woman past 40 also will present a problem. Her children have grown up, gone off to school or college. She feverishly throws herself into a round of bridge games, a literature or music club, with Wednesdays for the local charity organization, and becomes dissatisfied because there is no reality, no substance to the occupations at hand. Should she not be offered a chance to train herself for useful employment? Can’t we break down the taboo upon employment of women over 40?

On the one hand, we have urged that women stay at home and raise their families. That job done—what is there left for them to do? Still young and vigorous, they find themselves not wanted in a busy, active world. Pearl Buck has said that if American women were not to be allowed to fulfill their bent, whether it be for home making or professional life, they should not be given the educational opportunities they now have. I think she is right.

The woman past 40 is far from useless. As the records show, she can achieve much after 40—giving the first years of her life to her family. But the way is not easy. Society ought to make it uniformly possible for such women to use their talents, and this applies not alone to the professionally trained women.

Finally, what of the children of women workers? We all have heard or read of children locked in parked cars while their mothers work in war plants; children sitting through repeated performances in the movies until their mothers get home from the second shift; children locked in or out of homes day after day while both parents work. No one can deny that juvenile delinquency and destruction of home standards are rampant where you have such an emergency mass employment of women as the war machine has required. But need these things be? In a few communities where the labor market has been very tight the community has started nursery schools, food kitchens or other communal feeding, and supervised play periods, to make it possible for the mother of even small children to work. I think the whole situation should receive more intensive study.

Some people question whether children should be turned over to nursery schools and playground supervisors. There is plenty of precedent which will be cited. It will be said that children’s institutions are everlasting proof that even a poor mother is better than no mother. Social welfare organizations have learned this and instituted the system of “foster homes.”

But the fact remains that some women are temperamentally unsuited to caring for children, or untrained for housework, and having been in the business world before marriage, find themselves happiest in that life. Many children would be better off in a good nursery school than under the constant nagging of an irritable, because unadjusted, mother.

Many mothers come home to their children better able to give them affection and intelligent care because they have not had them all day long. But it is the rare woman who can successfully swing a job and a home with children. The problem pretty well boils down to one for individual decision. Although I believe most women will put the welfare of their children first, it seems only fair that society should provide a job opportunity for all who want to work or for all who must work irrespective of sex.

There are three courses we can follow. First, the Russian system, where all family life is subordinated to the needs of the State. Second, we can cling to the old idea that woman’s place is in the home and waste a lot of good citizens and make for more unhappy homes. Third, we can leave it to the individual choice and see to it that there are jobs for all who want them. This is a middle ground.

If we take this middle course there is still the need to emphasize that most young children will fare better in their homes—though the Russians might dispute this. But the important psychological element in this picture is that women would stay home only if that were their choice. If they wanted to work or had to work, the way would be open.

If Mme. Curie had not made such a choice the world might have lost one of its most distinguished scientists. I know it is not easy to do all three things. But I do not believe the children suffer under such circumstances as they are popularly supposed to. Mme. Curie’s children have achieved their own distinction, helped by the richness of the lives of their parents. All women should have a chance to make their choice of home, children or career—or all three.

GEN. EISENHOWER ANNOUNCES ARMISTICE

Capitulation Acceptable to U.S., Britain and Russia Is Confirmed In Speech by Badoglio

TERMS SIGNED ON DAY OF INVASION

Disclosure Withheld by Both Sides Until Moment Most Favorable For the Allies—Italians Exhorted to Aid United Nations

By MILTON BRACKER

By Wireless to The New York Times.

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, Sept. 8 —Italy has surrendered her armed forces unconditionally and all hostilities between the soldiers of the United Nations and those of the weakest of the three Axis partners ceased as of 16:30 Greenwich Mean Time today [12:30 P.M., Eastern War Time].

At that time, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower announced here over the United Nations radio that a secret military armistice had been signed in Sicily on the afternoon of Friday, Sept. 3, by his representative and one sent by Premier Pietro Badoglio. That was the day when, at 4:50 A.M., British and Canadian troops crossed the Strait of Messina and landed on the Italian mainland to open a campaign in which, up to yesterday, they had occupied about sixty miles of the Calabrian coast from the Petrace River in the north to Bova Marina in the south.

The complete collapse of Italian military resistance in no way suggested that the Germans would not defend Italy with all the strength at their command. But the capitulation, in undisclosed terms that were acceptable to the United States, the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, came exactly forty days after the downfall of Benito Mussolini, the dictator who, by playing jackal to Adolf Hitler, led his country to the catastrophic mistake of declaring war on France three years and three months ago this Friday.

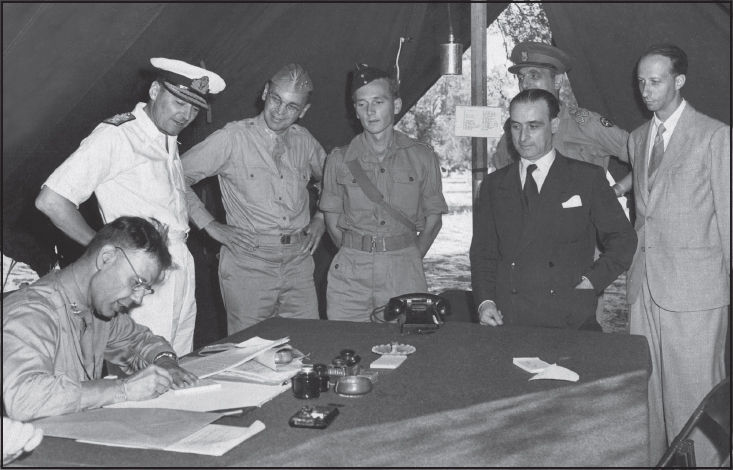

U.S. General Walter Bedell Smith (future director of CIA) signs the armistice between Italy and the Allied forces in Siracusa, September, 1943. Looking on, from left, English Commodore Royer Dick, U.S. Major General Lowell Rooks, English Captain De Haar, and the Italian General, in civilian clothes, Giuseppe Castellano, U.S. Brigadier General Kenneth Strong and the Italian officer of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Franco Montanari.

NEGOTIATIONS BEGUN SEVERAL WEEKS AGO

The negotiations leading to the armistice were opened by the war-weary and bomb-battered nation a few weeks ago, it was revealed today, and a preliminary meeting was arranged and held in an unnamed neutral country.

The Italians who had approached the British and American authorities were bluntly told that the terms remained what they had been: unconditional surrender. They agreed, and the document was signed five days ago. But it was agreed to hold back the announcement and its effective date until the moment most favorable to the Allies.

That moment came today, when the Allied Commander in Chief, in a historic broadcast, announced the armistice. He concluded with the reminder that all Italians who aided in the ejection of the Germans from Italy would have the support and assistance of the United Nations.

One hour and fifteen minutes after the General’s voice had gone out over the air, Marshal Badoglio faced a microphone in Rome and confirmed the armistice. He concluded with the promise that the Italian forces would oppose attacks “from any other quarter,” although they were laying down the arms that they had taken up against the Anglo-American armies.

MILITARY ASPECT EMPHASIZED

Although it was emphasized that the armistice was a strictly military instrument, “signed by soldiers,” it was disclosed that it contained a clause binding Italy to comply with political, economic and financial conditions to be imposed at the Allies’ discretion.

[It was believed that the armistice conditions were substantially the same as those imposed on France in 1940, which allowed the Germans to use all strategic French ports and military bases to wage war against Britain, The United Press reported.]

Immediately after the announcement of the armistice, the Allies made two appeals—one to the Italian people and one to the Italian Fleet—urging them to rally to a cause that was, in effect, the liberation of their own country. The appeal to the people was disseminated by radio and airborne leaflet, while that to the Navy was broadcast by Admiral Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham, the Allies’ Mediterranean naval commander.

The Italian people, particularly transport, railroad and dock workers, were asked not to give the slightest aid to the Germans. The men who man Italian ships received specific instructions how to bring their vessels into the protection of the United Nations.

Although the fear was proved unjustified by Marshal Badoglio’s broadcast, the Allies had taken no chances of a German move to forestall his giving the news to the people. As a safeguard, they had obtained from the Italians an agreement to leave one senior military representative behind when the others returned to Rome. This man is now in Sicily and presumably, had Marshal Badoglio not gone on the air, his representative would have broadcast the decision to the Italian public. As a further earnest of good faith, Marshal Badoglio had arranged to send the text of the proclamation that he made this evening to Allied Headquarters here. He kept his word.

1,181 DAYS AT WAR AND LOSSES

Italy quit the war after 1,181 days, during which she steadily lost territory and prestige. Last May 7, with the fall of Tunis and Bizerte, the last Italian soldier in North Africa was doomed. Since then, Sicily, part of Metropolitan Italy, was occupied in thirty-eight days.

The Italians endured two raids on military targets in Rome and felt the weight of 20,000 tons of bombs on the mainland in the past six months. Of this total, 11,300 tons fell in August alone.

But, despite the abject condition of the nation today, it was emphasized here, the Germans were still expected to fight on in the worst way. It would be wrong and dangerously foolish to regard Italy as geographically out of the war, even though she is so politically. Thus the Allies kept up the air war against Italian airdromes yesterday even though the effective time of the armistice was almost at hand.

Despite rumors of negotiations of one kind or another ever since the fall of Benito Mussolini, it may be said that the news of the capitulation struck this area with stunning impact. It was known that Italian resistance and morale, as evidenced by the Sicilian and Calabrian campaigns, were dwindling, but complete capitulation was something of which few persons outside General Eisenhower’s immediate circle had any idea.

Maj. Gen. Walter B. Smith, General Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, said at the close of the Sicilian campaign that one lesson had been never to give up the possibility of achieving surprise. That apparently applied to the news of the armistice as well as to that of military developments.

SEPTEMBER 10, 1943

MAFIA CHIEFS CAUGHT BY ALLIES IN SICILY

Coup, Led by U.S. Soldier, Helps to Break Black Market

Distributed by The Associated Press.

WITH THE AMERICAN FORCES IN SICILY, Sept. 9 —The Mafia, Sicilian extortionist gang that fascism tried for years to rub out and then incorporated as one of its own criminal appendages, has been smashed from the top.

Two of its notorious leaders, Domenico Tomaselli and Giuseppe Piraino, and seventeen district bosses were nabbed in a joint British-American coup in which Scotland Yard had a hand.

All of them are behind bars, and the responsible Allied authorities have enough leads on the other regional chiefs to insure their capture.

The Mafia men already jailed and those on the way to joining them controlled the black market, which still has a stranglehold on Sicilian life. It follows that breaking the Mafia gang means breaking the black market.

Within the secret society are men who have fought fascism since its inception, men of unquestionable integrity who shunned all ties with the sprawling majority of the fascistized profiteers. This group, genuinely interested in the future of Sicily, aided the coup.

Operations that led to the roundup began when the American Third Division, then on the Messina drive, chose Castel d’Accia, inland from Trabia, which is about twenty-two miles from Palermo, for its rear echelon headquarters.

Louis Bassi of Stockton, Calif., a technician in the special service staff, discovered that the tiny hamlet was nothing more or less than the Mafia fortress. He reported to his colonel, investigated by day and by night alone and reported again and again until he had accumulated enough evidence for an open and shut case against the racketeers.

We hope that Congress, returning to work today, will lose no time in putting itself on record regarding the main outlines of a post-war settlement. The stage is set for such a declaration. A clear statement of policy, made at this time with overwhelming bipartisan support, could help both to shorten the war and to win a better peace.

Before Congress adjourned for its midsummer recess the House had before it a resolution which had received the unanimous approval of its Foreign Affairs Committee. This resolution, introduced by Representative Fulbright of Arkansas, proposed that Congress go on record as “favoring the creating of appropriate international machinery with power adequate to establish and to maintain a just and lasting peace and as favoring the participation by the United States therein.” Since then an almost identical declaration has been adopted, again unanimously, by the Republican policy-makers in their conference at Mackinac Island. Republican support of the Fulbright resolution is thereby assured.

The great merit of adopting such a resolution now is that it would tell the world, before the fighting ends, that this time the United States intends to help enforce world peace when it is won. Such a declaration would strengthen the ties that now bind the United Nations. It would thereby help win the war. By encouraging our allies to put their faith in a new post-war alliance or a new league of nations, instead of attempting to find an independent and precarious security in the acquisition of new territory, it would help win a better peace.

SEPTEMBER 14, 1943

HARD-FIGHT RAGES IN SALERNO ITSELF

City Changes Hands Several Times in Day, But Allies Break Counter-Blow

TOWN FOUND DESPOILED

Germans Had Looted It of All That They Could Take in Earlier Withdrawal

By L. S. B. SHAPIRO

For the Combined Allied Press

IN THE SALERNO AREA, Sept. 14 (UP) —The town of Salerno was the scene of a violent battle yesterday and changed hands several times as the Germans fought with desperation.

German “ghost” formations, built around a nucleus of the battered remnants evacuated from Sicily, flung themselves against the advancing Allied forces in a desperate effort to prevent the exploitation of our beach-head. The effort failed against a quickly mounted Anglo-American defense line that sealed the Allied foothold.

Thus far in the battle, it is estimated that more than forty German tanks, mostly Mark V’s, have been destroyed in this area. The attack has been held off, after the bitterest of fighting, at some cost to the Allies. Warships off the coast have joined with the land forces to fling a withering barrage along the line of the German counter-attack.

Over the battle area the air fighting is the most violent that has been experienced since the closing days of the North African campaign. Dogfights swirl overhead continuously during the daylight hours, and the nights are filled with the flash of multi-colored tracer bullets reaching up at attacking planes.

Allied planes are gradually gaining domination over the area, but the German air force is battling with a daring that matches the desperate resistance of the German land forces.

An explosion during the invasion of Salerno.

‘MUSSOLINI’ SETS UP NEW KIND OF REGIME

Broadcast from Reich in His Name Creates ‘Republican Fascist Government’

TERROR REIGN INDICATED

Seizure of ‘Traitors’ Called for in Radio ‘Orders of Day’—Militia to Be Formed

LONDON, Sept. 15 (AP) —Italy’s ousted and invisible “Premier,” Benito Mussolini, apparently attempted to dethrone King Victor Emmanuel today in a proclamation) read in his name by a radio announcer, recasting defunct Fascism in Italy as the “Republican Fascist Party,” with Mussolini as its supreme leader.

The manifesto, read over a German-controlled “Fascist government radio” failed to mention the King by name, but the reconstitution of the party under the “Republican” label obviously meant that the King no longer ruled in the eyes of the Nazi-sheltered ex-Duce.

This action was in line with predictions that the new German-nurtured government would disestablish the House of Savoy and establish a republic. There was little likelihood, however, that the population, which joyously welcomed the end of Fascism, would assist in re-establishing the old regime.

REIGN OF TERROR INDICATED

The threat of “exemplary punishment of traitors and cowards” signaled that a reign of terror might be expected in Italy.

The appointment of Gen. Count Carlo Calvi di Bergolo as Governor of Rome—with German consent—to carry on the government failed to square with the previous German announcement that the “national fascist government” had been placed in charge.

Mussolini remained in the shadows. At last accounts he was reported to have gone to Berchtesgaden for treatment of a gastric disorder. Only yesterday the Germans said he was a very sick man whose condition had been greatly aggravated by his recent experiences.

NEW CABINET IS SET UP

German broadcasts reported to the Office of War Information by the United States Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service asserted that Gen. Calvi di Ber golo, puppet commandant of Italian forces in Rome, had formally liquidated the Badoglio Cabinet and named commissioners—all of them well known in the fascist regime—to take the functions and responsibilities of the Ministries.

The Mussolini decrees, said to be signed by the former Premier, were read over the German radio station Zeesen. They were read, not by Mussolini but by Alessandro Pavolini, former Italian Propaganda Minister, who was named in one of the decrees as “temporary secretary” of the new Fascist party.