Chapter 17

“THREE MEN OF DESTINY”

October–December 1943

B y late autumn of 1943 it was evidentthat the Western Allies were at last preparing to open up a major front in Western Europe. Speculation spread in The Times and elsewhere that George Marshall, Army chief of staff, would be posted to Europe to lead the final campaign to destroy Hitler’s Reich. “Soldier without Frills,” The Times called him, a modest, hardworking, sensible commander, but one who had yet to head up a field command.

The “Big Three” Allied leaders quietly planned two major summits to discuss the future military and political course of the war. While the meetings were being prepared, the campaigns continued, stuck—often quite literally—in the mud and sand of Italy, Ukraine and the Pacific. In the Soviet Union, the Red Army drove on through the harsh winter rains and snow to seize Kiev on November 7. By the end of the year Soviet troops had marched more than a hundred miles closer to the Polish frontier. Conditions in the Mediterranean theater were just as grim. “The front-line soldier I knew,” wrote the famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle in late 1943, “lived for months like an animal,” but one haunted by the “cruel, fierce world of death.” American troops were short of news from home, but anxious when it arrived. With an eye toward issues of morale, The Times published an article on “What to Write to Soldiers Overseas,” which concluded that regular hometown news and a good deal of affection were needed most. For soldiers whose wife or girlfriend wrote to say that she had met someone else, there were informal “‘Dear John’ Clubs” where the jilted men could drown their sorrows.

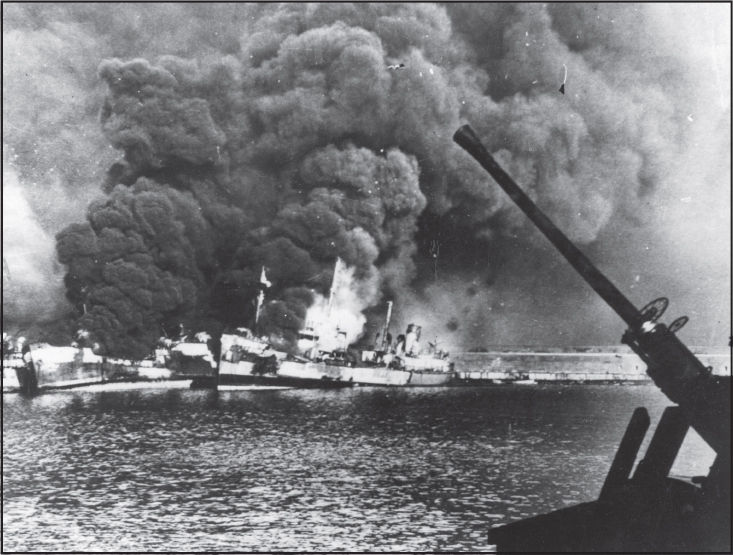

Conditions in the Pacific were, if anything, worse. Dogged Japanese resistance on small islands a long way from the mainland dimmed prospects of reaching the Japanese heartland. On November 1 American and New Zealand troops invaded the island of Bougainville. On November 20, some 35,000 Marines and soldiers tried to capture the atoll of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands in Operation Galvanic. The battle was fierce and for once American casualties were high compared with Japanese—1,140 Japanese against 4,700 Americans. The battle, one correspondent recorded, was “infinite and indescribable carnage,” with bodies and broken vehicles strewn across the narrow stretches of sand and coral.

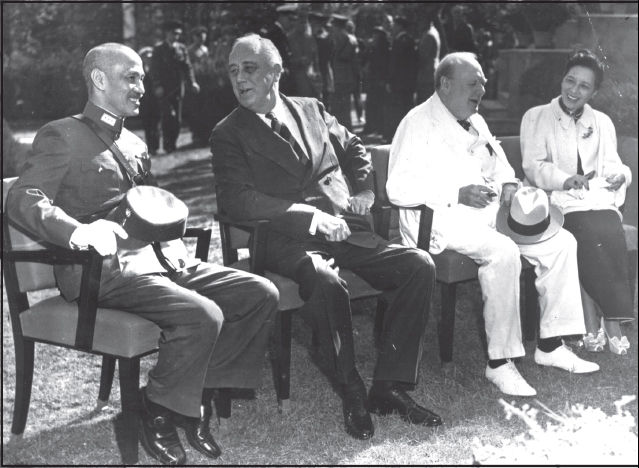

Against this backdrop, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill traveled first to Cairo, where they met with the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek to discuss the war in Asia, then, on November 20, to the Iranian capital of Teheran, where they met Stalin and his military staff. The “Three Men of Destiny,” as The Times called them, without exaggeration. Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin discussed the course of the war and its political consequences, which assumed increasing importance as the prospect of victory began to seem more likely. Stalin at last got a commitment from his Anglo-American Allies to launch a major invasion of Western Europe, relieving considerable pressure on the Red Army. Cyrus Sulzberger, reporting a few days after the final communiqué was issued (only two correspondents were allowed at the conference), noted in The Times that “Moscow’s long pleas for a second front are entirely answered.” Churchill had been less enthusiastic than Roosevelt about the prospect of invading Western Europe, but there was nothing he could do to stop the commitment.

By December The Times could report that the invasion plan in Britain was taking shape. Speculation about Marshall as the top field commander was shown in the end to have been just that. He remained in Washington, viewed as indispensable to the overall American war effort, and Eisenhower was transferred from the Mediterranean to take charge of the invasion, code-named in secret Operation Overlord. Facing him was his old enemy from North Africa, Field Marshal Rommel, who in December was put in charge of organizing the defense of the French coast.

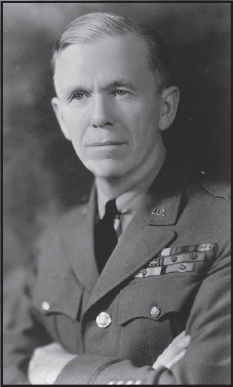

GEN. GEORGE CATLETT MARSHALL is moving toward the climax of his career. As one looks at the man and his record—a record of slow but steady progress—one senses clearly the reasons for his rise to eminence.

Not long ago occurred an incident which gives a sharp clue to the man’s character and methods. General Marshall was returning from Algiers. He took a look at the partly empty transport plane which was carrying him and a couple of other high-ranking generals and their aides back to the United States, and observed that it was a “crime” for those seats to be empty when there were so many wounded men who could be saved a trip back home on a slow boat.

In three minutes a young staff officer (the general had no aide de camp) was on his way to an Algerian hospital with orders to pick up some wounded enlisted men who would be able to travel sitting up. He came back with a couple of privates—one with his arm in a sling and the other with his head swathed in bandages. They got in and sat down. Just before the transport took off the general, who still has the powerful shoulders which helped make him an All-Southern football tackle in 1900, hopped into the plane, went over to the soldiers and, putting out his hand, said: “I’m General Marshall. Glad to have you with us.”

General George C. Marshall in the 1940s.

At the next base he heard of an injured second lieutenant who had been awaiting transportation home, so he loaded him into the plane, too. The somewhat awed patients all went to Walter Reed Hospital on their arrival in Washington. Three days later General Marshall, whose mind at the time was full of long-range plans for dislodging the Italians and Germans from Sicily and points north, took time off to call in a staff officer and have him check with the hospital on the condition of the two privates and the shavetail.

The tall, muscular soldier, who will be 63 years old next Dec. 31, is like that. He can be tough as the skin of a General Sherman tank; he can roll a head for incompetence as quickly and inexorably as the bite of a guillotine, yet he is one of the most considerate men in the Army concerning the welfare of his subordinates. His mind is a ready filing system of a vast amount of technical and personal knowledge, and by consulting this filing system he makes rapid decisions concerning men and matters. Dilly-dallying—either mental or physical—and General Marshall just don’t mix.

General Marshall also is one of the most untheatrical men in the Army. He has almost a fixation for unornamented language, and he never courts publicity. Men who work closely with him say that he has no phobias against publicity, but that (1) he does not want his work slowed up by the loss of time which would be consumed by posing for pictures, making numerous speeches or granting interviews, and (2) he does not want any monkey wrenches thrown into his delicate job by misconstruction, accidental or otherwise, of what he might say. He is reputed once to have remarked: “No publicity will do me no harm, but some publicity will do me no good.” If he wished, however, he could become a constantly publicized figure, for, in addition to his position, now one of the most important in the world, he has the background, the wit and the striking appearance necessary to capture the public fancy.

General Marshall’s habits on his frequent inspection trips are another clue to his character. He dislikes guards of honor and formal reviews, and will have nothing to do with either except when absolutely necessary. He likes to drop in unannounced on installations as he wants to see things as they really are. If a division commander, for instance, wants to show him a rifle range, he asks if any men are shooting on it. If the answer is no, he explodes: “Hell, I’ve seen a thousand rifle ranges—what I want to see is the men using it.”

He has a disconcerting habit of dropping in on mess halls and picking out his own mess hall for inspection so as not to be led into one that has been especially shined up for him. He has a passion for food conservation, and almost inevitably hops behind the counter to check up personally on how much food is coming back uneaten; if anything is wrong, he finds out what and sees that something is done about it. Similarly, if he learns in North Africa, for example, that a jeep motor is knocking because of slowness in delivery of certain parts, he will order an investigation of American camps all over the globe to see if those parts are generally slow in reaching the camps. And when he tells an officer he wants action on something, he doesn’t want to hear from the officer that that thing will be corrected next Tuesday; he wants to hear that it was done yesterday.

General Marshall was born at Uniontown, Pa., where his father, a Kentuckian, was a coal and coke operator. The young Marshall wanted to be a soldier as far back as he can remember, although he does not know just what influenced him. His father approved of his ambition, but, being a Southern Democrat in a period when the Civil War was still a strong issue, couldn’t get the local Congressman to send young George to West Point. So he went instead to the Virginia Military Institute, where, aside from his football prowess, he was First Captain of the Corps of Cadets. He distinguished himself during his freshman year by stoically keeping his mouth shut after a sophomore hazer ran a bayonet into his body and almost killed him. This same reticence still prevails, for none of the men who work with him (unless it be his most intimate colleagues, who won’t tell) ever heard him express himself on whether he would prefer to get out from behind his desk and into the field of action.

He was graduated in the class of 1901 and became a second lieutenant of infantry in the United States Army in February, 1902. He served with great distinction in numerous posts in the first World War, including the important job of Chief of Operations for the First American Army.

Something of his ability for organization and handling great bodies of men was shown in that post; he was responsible for the transfer of several hundred thousand men and their equipment from St. Mihiel to the Argonne in less than two weeks. He directed their movements by night and handled them so adroitly that the Germans were completely surprised by the presence of this large force when the Argonne offensive began.

He was extremely close to General Pershing, whom be served as aide de camp for a number of years. General Pershing, still one of General Marshall’s closest friends, recommended him in France for promotion to a brigadier generalship, but Marshall never rose higher during the war than his temporary rank of colonel, and, indeed, it took him nearly thirty-two years of Army life to achieve the permanent rank of colonel. In September, 1939, however, by which time he had become a brigadier general, President Roosevelt jumped him over the heads of thirty-one senior generals to become Chief of Staff. Five of the preceding fourteen Chiefs of Staff had been non-West Pointers, but General Marshall was the first V.M.I. graduate to fill the post.

General Marshall stands 6 feet and weighs 180 pounds.

SOLDIER WITHOUT FRILLS

His rather stern face has strong lines, more muscular than creased. His eyes are a pronounced blue. One of his great personality talents, particularly during the prewar years when Congressmen still were backward about voting large appropriations for the Army, is his ability to get along well with all kinds of men. He impressed Congressmen by his serious but courteous manner, by his willingness to give them what information they wanted; by the way he could pour out a flood of facts and figures in response to whatever questions they may have sprung upon him, and by the fact that he has the unmistakable air of a man who is telling the truth. The respect which General Marshall won from Congress has had a great deal to do with the rapid manner in which the peacetime Army of 174,000 troops which he took over in 1939 grew to its present status of nearly 8,000,000.

General Marshall is not the kind of man who can delegate all his responsibilities to his staff. However, he has sense enough to know he cannot personally handle thousands of details, so he has evolved a two-point system for meeting the situation: First, he selects as staff officers men who know his methods and in whom he has complete confidence, and, second, he has developed a way of having these men give him thumbnail outlines of current problems so he can grasp a situation without too much waste of time.

When an aide reports to General Marshall on a matter the general listens, then says, “Do it,” or, “Don’t do it.” He makes his decisions with lightning quickness and rarely explains why, and he expects them to be carried out immediately.

He has an incredible knowledge of the personal qualities of hundreds of generals, and his selections have been largely good. It is a tribute to his character that he has placed in high positions a number of men whom he does not care for personally but whom he knows to be good officers.

General Marshall is scrupulous about not granting favors in behalf of service men or officers requested of him by acquaintances or even close friends. He gets hundreds of letters asking such favors, but he replies, in effect, that “it would not be fair to the hundreds of people I have to turn down every day for me to grant this favor to you.”

The general has such abhorrence of any frills or excess verbiage in writing that it is not easy for any aide even to write a thank-you note for him. If anyone sends him a letter draft beginning, “Permit me to thank you,” the general will scratch it out and substitute, “I thank you.”

Almost everything that goes in to him for his signature comes back completely blue-penciled.

He insists on writing at least the bulk of his speeches and reports himself—and his recent 30,000-word biennial report to the Secretary of War was no exception. He once was so impressed by the clear, simple manner in which Maj. Gen. Terry Allen wrote an order during the Tunisian campaign that he sent a copy to President Roosevelt.

General Marshall has always worked very closely with Secretary Stimson. Their traits of integrity and devotion to duty undoubtedly have brought them near together. The general has also spent a good many of his luncheon and afternoon hours with President Roosevelt. There seems to have evolved a smoothly working relationship between the White House and the general, and some observers report that the White House has rarely suggested anything that is counter to War Department policy.

General Marshall has the happy faculty of being able to relax when he is away from his job. In Washington he has enjoyed long walks or canoeing on the Potomac with Mrs. Marshall. He also likes horseback riding and, on the rare occasions when he could get to his own home at Leesburg, Va. he has done hard physical work in the garden. He is an inveterate reader, not restricting his reading to military subjects. He can relax and read on his long plane trips. He admires the writings of Benjamin Franklin. He enjoys Sherlock Holmes, but not the ordinary whodunit, and he likes to reread books he has enjoyed. One work he recently reread was “The Three Musketeers.”

There are two other facts affording insight into the general’s character. One is that, while he is the holder of enough United States and foreign military decorations to fill a hat, he does not wear many. Among those always on his blouse, however, are the yellow pre-Pearl Harbor ribbon which every soldier who was in the Army before Dec. 7, 1941, is entitled to wear, and the Victory Ribbon, awarded to everyone who participated in the last war.

The other fact is that he employs no elaborate map system. He has a big globe and a few relief maps of the theatres where American armies are currently in action, but nowhere on any of them is stuck a flag, a symbol or so much as a colored pin.

The general doesn’t need flags and colored pins. He carries that information in his head and can tell you, right down to the last division, just what commander is leading what division behind what hill.

OCTOBER 3, 1943

What to Write the Soldier Overseas

By Milton Bracker

By Wireless from Allied Headquarters, North Africa.

Do’s and don’ts for those who want to give the news from home and keep up morale at the front.

The dourest dogfaces in Africa these days are strictly non-dues-paying members of the “Dear John” club. That the depth of their despair is matched by members of other chapters throughout Uncle Sam’s Army is entirely probable; but that does not matter. In this theatre their melancholy is supreme.

“Dear John” clubs are composed of G.I.’s—and officers, too—who have received letters from home running something like this:

“Dear John: I don’t know quite how to begin but I just want to say that Joe Doakes came to town on furlough the other night and he looked very handsome in his uniform, so when he asked me for a date—”

Obviously the letter has infinite variations, but the impact on the recipient is always the same. He is “browned off”—and a deep, dark, blackish sort of brown it is.

This cropping up of “Dear John” clubs is symptomatic of the effect mail has on a soldier, no matter where he serves and what his job. Probably the one most dominant war factor in the lives of most people these days is separation—a concept which to many who grew up in traditional American homes was virtually unthinkable before the war. Now sons, brothers, sweethearts, husbands and fathers from Maine, Carolina, Utah and Texas abruptly find themselves in places as unimaginable as Algiers. And the link between them and what they know and love best is much less an abstract patriotic ideal than a very tangible if often humbly written letter from home.

A long-legged G.I. lounging in front of the Red Cross club here the other evening was asked what kind of letter he liked most to receive. “Brother,” he said, and you knew at once he came from Carolina, “all Ah evah want is a lettuh.” As a matter of fact, soldiers repeatedly tell you they would rather have bad news than no news.

Recently an OWI bulletin was credited here with giving these suggestions for the kind of things to write soldiers: (1) How the family is doing everything to help win the war. (2) How anxious the family is for the soldier’s return. (3) How well the family is—giving details. (4) How the family is getting along financially. (5) What is doing in the community, news about girls, doings of friends, who’s marrying whom, exploits of the home team, social activities, effects of the war on the home town.

When Private John Welsh 3d of Houston. Tex, saw the bulletin he did a little letter writing himself, and what he did to the suggestions approximated what Allied blockbusters have been doing to German cities. Sgt. H. Bernard Bloom, a former Indianapolis advertising man, has some equally strong opinions on “type letters,” although the categories are his own, not ours.

Like his buddies, Bloom regards the “Oh, you poor boy” type as one of the commonest and “most disgusting.” This is the kind in which the correspondent “weeps over your body” before anything happens to it. He is equally bitter about the “I’m having fun” type. This is the kind of letter, first cousin to the “Dear John” species, in which the sender tells all about her gay whirl of parties, dances, cocktail parties, romantic walks in the park with Air Force officers on leave, etc. Bloom goes on to list the “Gee, things are terrible,” “I’m sorry to tell you,” “I wish I could be with you” and “Look up Cousin Zeke” type as others which plague him and his comrades.

But it would be grossly misleading to suggest that men in uniform are more critical of mail than appreciative. On the contrary, it means everything to them, and certain types of mail in particular can buck up a soldier more than any pep talk by his general. Soldiers carry their letters around with them, save them in footlockers, pull them out at mess table. Their faces light up when letters come, and drop when they don’t.

At the risk of attempting a formula, just as OWI did, it would appear safe to say most soldiers and Wacs like to get letters from their loved ones telling, first, that all is well at home; second, that the folks are proud of them—without laying it on thickly—and, third, amiable, chatty details of things close to the soldier’s peacetime way of life. And they like answers to direct questions they have written home; nothing is more exasperating than to ask for the specific address of a friend or how certain crops are doing and to have the query completely ignored.

In letters from their sweethearts and wives, soldiers want what every lover since the world began wants—that he is still the sole object of the girl’s affection, that she misses him and will wait till kingdom come. There is a difference of opinion on love letters as such, some soldiers saying they don’t trust girls who “give out a lot of that goo.” But they are not representative of those who have left behind sweethearts, fiancées and wives who mean the world to them.

There was a sergeant named Eddie whom I met in a London restaurant last spring, because they always double up male patrons who come along. He began telling me of the woman he had married just a month or so before leaving. He had a letter with him and in the few paragraphs he read aloud he somehow communicated more of the terror and beauty and solemn anguish of separated lovers than I have ever heard: “And so I don’t really worry about you, my darling,” his girl wife had written, “because I know that my husband is the best and the bravest and the strongest of all the men who have gone out to fight. Yes, and the gentlest. And I know God will not let anything happen to him because he is like that and because he isn’t anyone else’s husband. And that makes me very happy.”

Maybe the impact is not in the words themselves; perhaps it was in the way the boy read them, eyes aglow, his voice low. And perhaps you had to realize that he was a rear gunner in a Flying Fortress assigned to a station that had had and was having particularly heavy casualties.

Soldiers are more likely to be inspired and bucked up by personal things—how a namesake nephew is growing up or how the girl friend loved his picture in uniform—than by impersonal notes. They like to know how the war effort is continuing at home, but prefer to take for granted that it is going smoothly than to hear about strikes and wage arguments. They hate complaints about shortages of gasoline, rubber, candy, silk stockings or anything else.

One soldier here was infuriated the other day by a letter from a friend complaining that you could no longer get a hot dog big enough to see for a dime, while on meatless Tuesday you had to eat, etc., etc. “That so-and-so should have had what we had to eat in Kasserine Pass,” the soldier said, “and the sound effects, too.”

In general the men dislike the approach of those who write, “Don’t let anyone tell you we at home don’t know there is a war going on.” He doesn’t like to hear of his girl friend going out with other men, but he is likely to be pleased and amused by her lament that the only men left in town are “4F’s, old men and babies.” And he is also a sucker for all sorts of photographs of his family, his girl friend, his pets and friends, as well as for any clippings about him that may have broken into the local newspaper. Pictures and clippings never fail where written words may. One soldier said candidly his girl friend wrote him eight pages twice a week—and “frankly, after the first two pages I don’t know what the hell I’m reading.” He said he would prefer one V-mail letter every day and a longer letter every week or ten days.

OCTOBER 11, 1943

INDIAN CITIES MARKED BY SIGNS OF FAMINE

CALCUTTA, Oct. 10 (Reuter) —It is impossible to go from one place to another in famine-stricken Calcutta and Bengal without steeling one’s self to the indescribable sight of men, women and children lying where they fell from starvation, either dead or too weak to utter a sound.

There are fewer beggars in the streets, compared with several weeks ago, but thousands more are too ill to beg or drag themselves about. The Calcutta hospitals, which started to take in “sick destitutes” nearly two months ago, are now mostly overcrowded. Many doctors say that they have seen more suffering in the past month than in the past twenty years.

In the week ended last Thursday there were 527 deaths in the city’s hospitals. Countless bodies were picked up in the streets. From Aug. 1 to Oct. 6 two public organizations, one Hindu and one Moslem, together with police squads, disposed of 4,152 bodies, though they were not all starvation cases.

All care of the sick is being coordinated. At free rice kitchens, rice and vegetables are ladled out from huge spoons into the earthen bowls that are the only possessions of the thousands who crowd the kitchens. Some 1,350,000 persons are being fed by free kitchens in the province.

DANISH JEWS POUR ACROSS TO SWEDEN

Many Fugitives Are Pursued Through Jutland—1,600 Reported Already Arrested

FIGHTING IN COPENHAGEN

Stockholm’s Offer Of Haven, Ignored By Germans, Bars 2,000 Earlier Refugees

By Wireless to The New York Times

STOCKHOLM, Sweden, Oct. 3 —Fleeing the Gestapo terror introduced into Denmark on Thursday, more than 1,000 Danish Jews reached Sweden, most of them last night.

Braving the icy Oeresund, Jewish refugees of all ages and conditions arrived on the Swedish coast. Some even swam the strait—two miles wide at its narrowest point. Others were rowed across by Danish fishermen, who charged $375 to $750 for the passage.

Not all those who have tried to cross have succeeded. It is thought probable that most swimmers were seized by cramps and sank. Others crossing in boats were surprised by German Navy mosquito craft patrolling the strait and their boats were sunk by gunfire.

Jewish refugees in Malmo, Sweden, 1943.

The refugees said that when the Gestapo intruded on their new year celebrations, some Jews had resisted and both sides had had many killed. [Many are being hunted through Jutland, The Associated Press said.]

Municipal authorities and Red Cross branches in coastal communities in southern Sweden are lodging and feeding the refugees in schools and other available buildings. Many are destitute. Copenhagen reports said that the Gestapo had concentrated on poorer Jews, apparently giving those who could afford to pay huge ransoms a chance to negotiate.

Travelers reaching Sweden tonight said that Heinrich Himmler had arrived in Copenhagen to superintend the round-up of Jews but this was not confirmed by any other source.

OCTOBER 12, 1943

BISHOP DESCRIBES HONG KONG HORROR

O’Gara Gives Details Of His Escape From Execution And Suffering In Japanese Camp

MAKES PLEA FOR CHINESE

Urges Repeal of Exclusion Act and Wants U.S. to Exercise More Influence After War

Recounting the story of his narrow escape from execution and subsequent ordeal as a prisoner of the Japanese, Bishop Cuthbert O’Gara, the Vicar Apostolic of Yuanling and head of the Passionist Missions in western Hunan, China, urged in an interview yesterday that the Chinese Exclusion Act be repealed and also advocated greater American influence in China through offering “cultural and technical assistance to Chinese institutions of learning.”

The interview took place in the offices of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, 109 East Thirty-eighth Street. Bishop O’Gara, who was born in Ottawa, Ont., and is 57 years old, has recovered from his six months of internment by the Japanese at Hong Kong. He expects to return to his post in Yuanling after a stay of two or three months here.

20 YEARS IN CHINA

Bishop O’Gara has been connected with the missionary work of American Passionist priests in China for twenty years and has received high praise from the Chinese Government for his relief activities on behalf of the refugees driven into the interior by the Japanese invaders.

He told of the “fine impression” American airmen and soldiers have made on the Chinese population, both for their fighting ability and faithfulness to their religion.

The Bishop explained that he had flown from Yuanling to Hong Kong for medical treatment eight days before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“I was at our Catholic hospital in Stanley, just outside Hong Kong, on Christmas morning, 1941,” Bishop O’Gara continued, “when the Japanese took me prisoner along with thirty-two of our missionary priests and brothers. We were stripped to our underwear and our hands were bound behind our backs.

“We were taken to a firing line and kept there for about an hour and a half. Then we were questioned and afterward we were put in a garage near by, with our hands still bound.

“I don’t know why we were not executed unless it was because Hong Kong surrendered that afternoon—a few minutes after six British officers were bayoneted to death. We expected it to be our turn next.

REMAINED BOUND FOR TWO DAYS

“For four nights and three days we were kept in the garage, still in our underclothes, and for two of those days our wrists remained bound behind our backs, while we were given nothing to eat. On the third day our captors gave us a little milk and hardtack.

“Then we were given outer garments and taken to a dark, filthy Chinese hotel, exactly thirteen and a half feet wide and four stories high. For three weeks we were interned in this place, four prisoners to a cubicle measuring 8 by 10 feet and crawling with vermin.

“After that horror we were moved to a big concentration camp, which hardly deserved its designation by the Japanese as the Stanley Civilian Recreation Center, although it was a great improvement in our lot as prisoners.”

Bishop O’Gara said he believed his release, after more than five months in the internment camp, was brought about “through the good offices of the Holy See.” His physical condition then, he said, made it necessary to remain in Hong Kong another month as the guest of the Italian bishop there, Enrico Valtorta.

Asked how he felt about the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Bishop replied: “I feel rather keenly that if relations between China and the United States are to be built on mutual admiration and respect, obstacles such as the Exclusion Act should be removed from the way of a better understanding.

“In the reconstruction period after the war there is much that the United States can do to aid the Chinese. It can give cultural assistance in the way of educational facilities and technical development.”

Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the new China, turned to Russia for aid after his first appeal to the United States was virtually ignored. Consequently there has been a strong Russian influence in the new China’s development, especially in the last twenty years.

OCTOBER 15, 1943

ARMY GETS BOMBERS DWARFING FORTRESS

B-29 Carries More Explosives and Can Range Deep Into Enemies’ Territories

FULL REIN IN 1944 LIKELY

Output Rate Rising But No Let-Up in Liberator and Boeing Production Is Planned

By The Associated Press.

WASHINGTON, Oct. 14 —A new American super-bomber carrying more explosives and having greater range than any existing war-plane is in actual production.

An unspecified number of the new giants have been delivered to the Army within the last few weeks. An increased rate of output is scheduled for this month.

Dwarfing the Consolidated Liberator and the Boeing Flying Fortress, the new dreadnaught of the sky is reckoned to be capable of bringing the innermost production centers of Hitler’s European fortress and the Japanese Empire within reach of United States bombardiers.

The plane has been identified as the B-29 by the Army weekly newspaper Yank in a recent article which said:

“A new super fortress, the B-29, is being built which will have a greater bomb capacity and longer range than any existing bomber.”

From previous guarded reports which have cleared military censorship, it appeared that officials did not expect to see the new airplane in combat before 1944. This is presumably because of the time required to attain full-scale production, train crews and eliminate any “bugs” which may show up in the early models,

A prediction that the new heavyweight puncher would be “the determining factor in crushing Germany” came last summer from Capt. E. V. Rickenbacker, World War ace. In June he told the Tenth United States Army Airforce in New Delhi, India, that the new bomber would join the Liberators and Fortresses in 1944.

He also told the American pilots and crewmen that the super-bomber would have double the load and fighting power of the planes they were flying and was especially designed for bombing Europe.

“No nation could survive the pounding a fleet of these planes can deliver and they will be out in mass production next year,” Captain Rickenbacker said.

Any statistical comparison of the new plane with the flying fortress is unobtainable at this stage, but Gen. H. H. Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, several months ago gave a tipoff to the difference in his remark that Liberators and Fortresses are “the last of the small bombers.”

Introduction of the new bomber into the United States’ aerial arsenal will not mean the tapering off of production schedules of present-day bombers, it was made clear recently by Charles E. Wilson, executive vice chairman of the War Production Board. Revealing in May that heavy bomber output by April would be eight times greater than in April, 1942, Mr. Wilson added:

“This does not include the scheduled output of the new super-bombers.”

Production of Liberators and Fortresses reached a righ record in August, the WPB revealed more recently, with a gain of 11 per cent from July. Over-all aircraft output in August was 7,612 military planes.

It was recently disclosed, also, that the Flying Fortress was undergoing changes to increase its bomb load to ten tons, making it, the heaviest in the world—until, presumably, the super-fortress gets into the fighting.

A B-29 bomber takes off from the air base at Saipan destined Tokyo in 1944.

OCTOBER 20, 1943

Editorial

THE BATTLE OF THE DNIEPER

It was just about three weeks ago that Hitler reappeared on the Russian front and supposedly gave orders that the Dnieper line must be held at all costs. And for three weeks now that river has been witnessing one of the fiercest battles of the whole war, in which the resources and the endurance of both sides are being tested to the utmost. The Russians, with a stamina that is all the more remarkable because they have been fighting in a victorious advance since the middle of July, have succeeded in crossing the river at four points and have established bridgeheads which all the German counter-attacks have been unable to eliminate. This drive is synchronized with another farther south, against Melitopol, where bitter street fighting is proceeding now. Together, the two great drives constitute a pincer movement which, unless checked, would endanger the whole German position in the Crimea and force a further precipitate retreat.

Yet it is also evident that, having determined to make a stand, the Germans have been able to put up a resistance which testifies to their continued strength and dampens hopes for their quick defeat. We have still to see the whole significance of the Dnieper River battle. Did the Germans actually decide to hold the Dnieper line “at all costs”? Or did they seek to hold it only to gain time in order to extricate their armies from the Crimea and then continue their retreat to the so-called Moltke line from Lake Peipus, or possibly Riga, to Odessa?

Only the result of the battle can provide the answer, and any indications of what the answer will be are undoubtedly being watched with the keenest interest by the three-Power conference in Moscow. For to the Russians a crumbling of the Dnieper front would be a demonstration that all that is necessary for a quick victory is another front in the west, since the Germans would be shown to be no longer able to stem any determined assault in force.

NOVEMBER 1, 1943

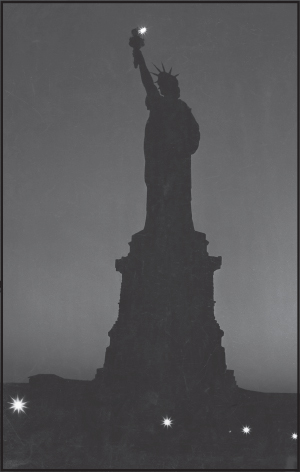

DIMOUT ENDS TODAY EXCEPT BY THE SEA

Police Get Rules for Voluntary Compliance—Street Lights to Be 90% Normal

New York Police Commissioner Lewis J. Valentine issued to all borough commanders yesterday a ten-point set of instructions for their guidance in obtaining voluntary compliance with the “brownout” that is to go into effect today to conserve electricity as a substitute for the dimout that has been in effect for eighteen months.

These instructions revealed that shields would be removed from all traffic lights except those visible from the sea; that street, parkway and bridge lighting would be restored to 90 per cent of normal except where visible from the sea; that masks might be removed from automobile headlights and that the Police Department would take many steps to conserve electricity and thereby reduce the consumption of coal.

OBSERVANCE TO BE VOLUNTARY

The orders issued by Mr. Valentine made it plain, however, that observance was to remain on a strictly voluntary basis. They provided that when a member of the department discovered a violation of the recommendations for business establishments and electric display signs, he was to warn and admonish the offender when possible.

Under no circumstances is a summons to be served or a summary arrest made of any offender, according to the orders. Instead, reports of violations are to be filed in alphabetical and numerical order of the streets and avenues in each precinct. The orders provide that the precinct commander “shall take such further action as may be necessary to insure compliance with these instructions.”

The instructions set forth that the engineering bureau of the Police Department was removing shields from traffic lights as rapidly as possible, and that street, parkway and bridge lighting would be restored to 90 per cent of the pre-war normal as measured in kilowatt hours. The excepted areas include those parts of the Rockaways, Coney Island, the south shore of Brooklyn, and the east and southeast shores of Staten Island that are visible from the sea.

AUTO HEADLIGHT INSTRUCTIONS

Masks may be removed from automobile headlights, according to the instructions, but under no circumstances will other than parking lights be permitted along the coast showing seaward. In all other areas low-beam headlights will be permitted, Mr. Valentine noted, as already announced, that subway and elevated trains, surface cars and buses would return to normal prewar lighting.

Outdoor advertising, promotional and display sign lighting will be eliminated in the daytime as well as at night, the instructions disclosed. Electric signs necessary for the identification of places of public service, however, such as shops, stores, theatres, restaurants, public lodging establishments and transportation terminals, may be operated for two hours between dusk and 10 P.M.

Show window lighting must remain as at present and not be increased in intensity, according to the Commissioner’s instructions, but the issuance of (A) and (B) certificates for show windows will be discontinued.

Lighting of marquees and building entrances will be eliminated completely in the daytime, and will be reduced as much as is consistent with public safety at night, according to Mr. Valentine. He also directed that lighting of outdoor business establishments be eliminated completely in the daytime and reduced as much as possible at night.

“Occupants of residences and hotels are to turn off lights when not actually needed and eliminate waste in the use of various electric appliances in homes,” the instructions continued.

“Commercial and industrial customers are to turn off lights and appliances when not actually needed. Note: Army air raid regulations require that, at all times, during the hours of darkness, occupants of premises and operators of road vehicles and other conveyances shall not have any unattended lighting.”

The police commissioner also announced that the present speed laws of twenty miles an hour at night and twenty-five miles an hour in the daytime would remain in effect except where properly authorized signs indicating greater or lesser speed limits were posted.

MAYOR SOUNDS A WARNING

Mayor La Guardia, in his weekly radio talk over Municipal Station WNYC yesterday, warned that it might be necessary at any time to return to the dimout regulations and that “we will continue to have air raid drills.”

The public was told not to expect street lights to return to their former brilliancy immediately. The Mayor cautioned that it would be some time before the entire 70,000 bulbs that are required would be obtained. He said the first batch would be delivered next Monday.

The Statue of Liberty lit only by her torch of two 200-watt lamps instead of the usual thirteen 1,000-watt lamps and pier lights, on Bedloe’s Island during New York City’s wartime lighting dimout to conserve energy costs.

The Mayor disclosed that he was now receiving in his mail “kicks” against the suspension of the dimout, some complaints going so far as to say the dimmed-out lights in subway trains were good for the eyes.

“How would you like to be Mayor of New York?” he asked. “Well, let’s say it’s funny, because if you didn’t think these things were funny you’d just go plain crazy. No matter what we do, the mail continues and the protests continue.”

NOVEMBER 2, 1943

WAR-CRIME TRIALS SETTLED BY ALLIES

Russia, for First Time, Takes Definitive Stand With the Other Major Powers

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, Nov. 1 —The three-power declaration on German atrocities, the most strongly worded yet issued on the subject and the only one in which Premier Stalin has directly participated, defined today for the first time the jurisdiction over the responsible individuals and the time for their trial and punishment. Those questions were left unsettled in a similar Anglo-American declaration published last Aug. 29 and in earlier warnings made individually by the President and Prime Minister.

While the Russian Government, by various means, had previously made plain its agreement on the general principle of the punishment of war criminals, the lack of complete mutual understanding had been reflected in such incidents as Russia’s demand for the immediate trial of Rudolf Hess, Deputy Fuehrer of Germany, after his capture in England.

Today’s statement made it clear that Russia now agreed with the United States and Britain that the punishment of war criminals should await the armistice and that jurisdiction would be delegated to the respective countries wronged instead of to an international tribunal, as had been suggested unofficially. The statement mentioned various atrocities perpetrated by the Germans in countries that they have overrun, emphasizing particularly the “monstrous crimes on the territory of the Soviet Union.” In the name of the thirty-three United Nations, it gave “full warning” to the Germans.

Detailed lists will be compiled in all the wronged countries, especially the overrun parts of Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Greece, Crete and other islands, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France and Italy.

Thus, the statement pointed out, the war criminals will know that they will be brought back to the scenes of their crimes “and judged on the spot by the peoples whom they have outraged.”

WITH UNITED STATES MARINES ON BOUGAINVILLE, Nov. 1 (delayed) —The first Marine dog platoon went into action when the Marines landed today on Bougainville Island, last major Japanese stronghold in the Solomons.

The dogs included twenty-one Doberman pinschers and three German shepherds under the “command” of Lieut. Clyde Henderson of Breckville, Ohio.

Part of the platoon was divided into scout, messenger and first aid units. The first unit will be employed to smell out enemy nests. The second will carry messages to rear headquarters. The third searches out wounded who have crawled to cover.

Lieutenant Henderson said this was the first time a trained dog unit had been employed in this war by American armed forces.

NOVEMBER 21, 1943

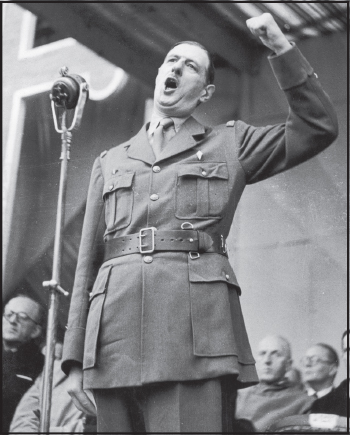

Three Men of Destiny

On Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin depend the shape of things to come—three men of sharp contrast, but alike in the power they wield.

By Anne O’Hare McCormick

The stage is set for one of those great occasions on which history hinges. Preparations have long been under way for a meeting of the three men who are the spokesmen and the symbols of the three most powerful nations on earth. Since the Moscow conference of their Foreign Secretaries it has been clear to all the world that they have an appointment with one another—and with destiny.

It is easy to visualize a meeting of the men, from points very far apart in time and space and ideology, sitting down for the first time at the same table to discuss the future of the world. In the background is a vast panorama of battle—the pounding of the Red Armies driving the Nazis out of Russia, the roar of German cities going up in smoke, the fire of Anglo-American guns blasting the road to Rome. As war commanders, Franklin Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill are acutely conscious of these mighty movements in the field. They know that a decisive shifting of pressure from the Eastern to the Western front is in full progress. But though war has made them allies, almost without their own volition, the primary purpose of their meeting is not to discuss war strategy. The military plans are made and the issue of the conflict is beyond doubt. What at last brings the three leaders together in person is the certainty that the war is won.

This is the great significance of the conference. It is a peace conference, held to confirm and fill in the outlines of the agreements signed by the Foreign Ministers in Moscow. Since it could not take place until a basis of agreement was reached, it is a dramatic notification to the world that the victors are resolved to perpetuate their partnership and work out a joint strategy for victory.

Here is a scene that will live as one of the famous conversation pieces of our epoch. The table is likely to be smaller and the conversation more private and informal than in the Hull-Eden-Molo-toff meeting. In the most important talks the three men will probably be alone except for an interpreter or two. Stalin always provides his own, and while the necessity of translation will slow up the give-and-take, it will not dam the flow of discussion. The President and the Prime Minister are fluent, highly expressive men who relish the flavor of their own phrases. Stalin, for all his reputation as a man of mystery, is by no means a man of silence. He has the blunt decisiveness of a leader who is never contradicted, but he was trained in the Marxist dialectic and he is given to embroidering his points with copious arguments.

Even the shapes of the faces are a study in contrasts. The round, cherubic countenance of the Briton differs as sharply from the square, pock-marked visage of the Georgian as both do from the oval, smiling face of the American. Stalin’s cool eyes are watchful under a grizzled brush of hair. As he sits calmly smoking his pipe, the effect of power in repose heightened by occasional slow, lithe, panther-like movements, he does not miss a gesture or expression.

The President’s eyes are cool, too, and slightly quizzical. He makes large gestures with his long-holdered cigarette, and appears more casual and at ease than the others, but his unquenchable curiosity and his interest in this encounter, which he has desired for years, make him as alert as Stalin. Churchill listens with half-closed eyes, slumped in his chair. He chews his fat cigar more than he smokes it, and this gives him a slightly ruminant air. But nothing escapes him either, and his opinions are delivered with a flash and vigor that show the high tension of his mind.

These are the men cast by destiny to play stellar roles in the tremendous drama of war and peace. They are alike in the power they wield and the massive self-confidence with which each in his different way exercises his authority. Stalin is the absolute dictator, master of a party machine that has welded “all the Russias” into a unity and force they never knew before. He stands guard over the biggest land mass on earth, a living Colossus of Rhodes who straddles two continents and links them into one.

There is not the slightest prospect that he will modify the system which has proved stronger under the test of war than even he could have predicted. Obviously it gives him an advantage in negotiation over the heads of democratic governments, who can never decide anything with the same finality, or speak without looking behind their shoulders at their parliaments and their public.

Yet the war, while it has increased Stalin’s popularity, has in some degree diminished his power. It has obliged him to take more people into council—the military chiefs, the directors of the war industries, the spokesmen of soldiers, refugees, peasants—and the effect of this wider consultation, plus the force of events, is clearly visible in the changes that are taking place within the Soviet system while the fighting goes on.

By the same logic the war has given authority very like that of a dictator to Mr. Roosevelt and Mr. Churchill. They have been obliged to assume extraordinary powers, to make secret plans and decisions, to impose military censorships that often lap over into civilian fields. Total war applies its own rules, its own uniformity. Hence, as war leaders, the three statesmen meet on a basis nearer equality of function than would be possible in peacetime.

All three, moreover, are by nature men of strong will who are irked by interference. Roosevelt cloaks his masterful temperament in an amiable manner. Stalin’s steely hardness is hardly concealed by his level voice, his lusty humor and the genial prodigality with which he dispenses Oriental hospitality. Churchill is much more the bulldog type than either. He is John Bull in person, short, round, rosy, a mighty trencherman and a mighty talker, whose eloquent tongue lisps in private conversation, but not in hesitation, and always in the ringing rhythms of Milton and the King James Bible.

Such likenesses are not strange in leaders who are not where they are by accident. They have forged their way to the top because they are rulers by will and temperament. What is strange is that they have reached their present eminence, truly awful in its responsibility, from such different backgrounds and by such different processes. The representatives of democracy are both aristocrats. Churchill likes to think he is half American, but he is English in every fiber of his being and every turn of his thought.

He has not always belonged to the Conservative party, but he is nevertheless a true Conservative and a professing imperialist in the British style, which is ample enough to adapt itself to new conditions. He has not always held office, and but for the war would never have realized a lifelong ambition to be Prime Minister. Yet he has always been in politics, a passionate parliamentarian. In their lives and thought and view of government there is no common meeting ground between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin.

Roosevelt and Stalin have a point of contact in that both are more adept politicians than Churchill. They share a relish for politics as a game. The Soviet leader gained control of the Communist party and changed its direction by adroit and patient manipulation: Under entirely different conditions, the President’s skill as a political maneuverer has changed the political alignments in this country without changing the party labels.

But there the likeness ends, Roosevelt typifies the oldest and solidest America. His Groton-Harvard-Hyde Park background is near Mr. Churchill’s, but as remote from Stalin’s as the White House is from the Kremlin. Neither Churchill nor Roosevelt can have even an imaginative conception of the life of the cobbler’s son of Tiflis who grew up as a conspirator, holding up banks and organizing underground revolution in Czarist Russia while Lenin and the intellectual leaders of the revolution were producing its literature abroad.

The two democratic statesmen are types and products of a world that Stalin has never known, and he is the product of a world that they have never known. Roosevelt and Churchill have flourished in the upper strata of a free society, have traveled widely, have reached their present position through the smooth working of a well-established democratic system. Stalin fought his way up from the underground; he is the first guerrilla leader come to power. Perhaps the most vital hiatus between them as they talk is that the Englishman and the American know the world and do not know Russia, while the Russian knows Russia and does not know the world.

The President, asked not long ago what he would say to Stalin when they met, replied that to begin with he would announce that he was a realist and intended to discuss the problems that had to be dealt with in common on the basis of realism. This is a tribute to Stalin as the “great realist.” But it implies that his definition of realities is the same as ours. On the question of Russia’s western borderlands, for instance, the Soviet position is very clear. Not only the Moscow press and other Soviet spokesmen but Stalin himself has announced that the frontiers they claim are beyond discussion. This may be true for Russia, but the President and the Prime Minister are uncomfortably aware that they are not beyond discussion in Great Britain and the United States.

This is only one of many ticklish questions on which there will be one mind in the Soviet Union and opinion will be divided in the democracies. It illustrates the difficulties that will have to be faced and surmounted in these conversations. For agreement must be reached on some terms if the coming victory, purchased at a price that is still far from paid, will lead to the peace and order the three powers and their representatives are working for. The quest for peace is the reality overshadowing all lesser considerations, and if the three statesmen convince one another that this is the paramount aim of all, they will proceed in an atmosphere of confidence in which all problems are arguable—and soluble.

Can men coming together from points so far apart, shaped by personal experiences and systems of life so different, driven together only by the attack of a common enemy and carrying with them so many old suspicions and reservations, create the atmosphere of agreement?

The answer is threefold. In the first place they have sought this rendezvous. Slowly, even reluctantly, it has grown out of a decision that must be a tripartite decision or the meeting would not take place. The decision is that the safety of Russia, Great Britain and the United States requires that they shall work together to win the peace as well as the war. Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill are above all representatives of the supreme national interests of their respective countries. They are convinced that the cooperation they seek from one another constitutes the minimum guarantee of “peace in our time.”

The second part of the answer is to be found in the aspirations of the statesmen themselves. It is a fact of prime importance that all are inclined to view themselves in the light of history. Churchill is a historian. He has studied with minute care the career and character of his ancestor, the Duke of Marlborough, and he can hardly help thinking of himself as the second of his line to take his place among the immortals in the story of England. Certainly his speeches are addressed as much to the reader of tomorrow as to the listener of today.

In the first year of the war, while waiting to see Churchill in the library of Admiralty House, I picked up from the table the book in which he describes his early life. When my turn came I told him I found the story so interesting that I was almost sorry to be interrupted. Immediately he offered to give me a copy of the book. “But no,” he said on second thought, “if I give you a book it won’t be that one. I’ll give you a volume of my speeches because they are historic documents. It is by my speeches that I shall be remembered in history.”

To listen to Stalin talking of Lenin, and of himself as the successor of the founder of the Soviet State, is to understand that he, too, considers himself a chosen instrument of history. The true Communist sacrifices himself to posterity as eagerly as the true Christian bears the sufferings of this life in anticipation of rewards in heaven. If Stalin is no longer the single-minded Communist, it is because he has become the heir of Peter the Great. He has banished the Old Bolsheviks in favor of the heroes of imperial history beause he beholds Russia today as a great, perhaps the greatest, power in the world and himself as a towering figure in the pageant of that greatness.

The President’s sense of history is very strong. Long before the war, from the beginning of his administration, in fact, he thought of himself as one of the small company of American Chief Executives destined to loom large in the record because they preside over periods of convulsive change. Perhaps this premonition of immortality came from his triumph over physical disability; perhaps from the crisis in which he was inducted into office. As time passed, at any rate, it grew stronger. The part he felt elected to play became not simply an American but a world role.

Neither Stalin, the triumphant revolutionary who revitalizes the power of Russia, nor Churchill, the triumphant Conservative who restores the prestige of the British Empire, has a greater sense of mission and of destiny than Franklin Roosevelt. Perhaps he thinks in even larger terms than they do. Certainly he is more attracted by large ideas and global plans. His field for the Four Freedoms is “everywhere in the world.” So he is likely to be more stirred than the others by this meeting not merely because he responds to drama but because he is playing there the role he most covets. Roosevelt would like to go down in history as the great peacemaker. For a long time he was lukewarm to the Wilsonian dream, and he is much readier than Wilson to compromise with the ideal. Yet in a strange way—strange because it shows that in spite of our defection it is indigenous to America—it is still the same dream. Roosevelt also yearns to be the founder of a world peace system.

On two counts, therefore, because the three men aspire to a large niche in history, and because they believe cooperation is a safer national policy than isolation, there is reason to hope that they will strive hard to agree on the concrete decisions left suspended at the Moscow conference.

The unanswered part of the question depends on more imponderable factors. It depends in no small part on what might be called the intra-relations within the Big Three, the personal impressions they make, the impact of the mind and manner of each upon the others. The Prime Minister and the President are already friends. Churchill did not get on too well with Stalin when he went to Moscow at the height of the Russian dissatisfaction at the failure to open the second front. The picture is different now. But what effect will the Roosevelt charm have on Stalin?

Winston Churchill has frequently mused aloud on the fate that has pushed the President, Stalin and himself into a relationship none of them could have foreseen when the war began. It strikes him as extraordinary that this oddly assorted trio should be brought into conjunction and given a joint control of a great crisis in the destiny of mankind.

It is extraordinary that a few men should exercise so much power that the interplay of their ideas and their personalities should be so important as it is. It is extraordinary that so much should depend on how they get on together at this historic parley. But that is so only because they are all alike instruments of great forces and symbols of the desperate hopes of peoples that these forces can be controlled and used henceforth for construction instead of destruction. Whether they can work together depends, finally, not on three men, however powerful they are, but on the will of the great nations they represent.

DECEMBER 2, 1943

SCENE OF PARLEY LIKE ARMED CAMP

Each Delegate’s Villa and Hotel Where Sessions Were Held Under Heavy Guard

By Cable to The New York Times.

CAIRO, Egypt, Dec. 1 —Not since the days of the Ptolemys has Egypt been such a cynosure of attention from the civilized world.

The fact that something big was about to happen was a wide-open secret in the rumor-ridden cities of the African periphery for weeks. Finally, after a flood of rumors, it was blandly announced on the morning of Nov. 22 that Prime Minister Churchill, President Roosevelt and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, accompanied by their principal military advisers, had arrived here.

CHIANG FLIES IN AMERICAN PLANE

Dr. Hollington Tong, the Chinese Vice Minister of Information, then told about the Generalissimo’s first visit thus far west except for his trip to Moscow several years ago. The Chinese party came in two four-engined American planes with American crews. General Chiang’s plane arrived at 7 P.M. on Nov. 21. Mme. Chiang was not in good health but felt that her presence was needed. Only two long stops were made on the four-day journey, General Chiang’s first from China since his trip to India in 1942.

Major George Durno, a former White House correspondent who is handling Mr. Roosevelt’s press relations, then spoke of the President’s trip. There was a sudden hush when he quietly stated that not only the President but the Army and Navy staffs were here. “The President requests you fellows to have lots fun for three or four days, then get your answer at a press conference,” he said.

Mr. Roosevelt arrived on the morning of Nov. 22 by plane. Rear Admiral Wilson Brown, his naval aide; Rear Admiral Ross Mclntyre, his physician: Harry Hopkins, Rear Admiral William Leahy and service men came with him. The plane was protected by fighters.

PLANE BROUGHT SPECIAL JEEP

It taxied up to an enormous concentration of jeeps, armored cars and guard patrols blocking all points as Mr. Roosevelt’s special jeep was unloaded from the huge plane. The President then drove off past lines of soldiers guarding the road with their faces sternly pointed to the desert. Not a single eye peeked at the road for a glimpse of the visitor as the armored cars swirled protectively through the desert.

Mr. Churchill, who had arrived the previous evening by warship at Alexandria, having called at Gibraltar, Algiers and Malta, was accompanied by a party that included his daughter, Sarah Oliver, and Ambassador John G. Winant. The ship had a special cipher staff and map room, permitting the Prime Minister to carry on his regular work.

The three Allied leaders took time from their talks to visit the Pyramids and the Sphinx.

The President stood the journey well. He had never been so far east, Major Durno said.

The President saw Mr. Churchill first on the afternoon of Nov. 22 in his villa. All the leaders met in their villas, compared to the general conferences.

34 VILLAS, ALL GUARDED

At 10 A.M. on Nov. 23 the chief of the Office of War Information in Asia took up the story with a description of the physical set-up of the conference. “There are thirty-four villas in the hotel’s general vicinity,” he said, “with its own guards around each one in which the ‘big shots’ live. Each villa can be considered a separate defensive area protected by British and American guards. The whole region is a general defense area protected by its own guns and searchlights.

“Right alongside the peasants laboring in the cabbage and corn fields, there are ack-ack batteries. Near the road turn-off British and American M.P.’s are on sentry duty. One needs two passes to penetrate beyond there—a special delegate’s pass and your own identity paper. After that, accredited visitors are again stopped twice before they are admitted to the hotel.”

Within the hotel were the service agencies: billeting, transportation and information desks. Observers’ desks, for those officials reporting the occasion to the world, were in the corner. On the left was the bar.

The main conference room was back near the dining room, in a former salon. Other conference chambers were on the left. An American Army post exchange was set up in a corner. Conference Room No. 1 was a big private dining room with twenty-eight seats grouped around a green-baize-covered table.

Both the dining room and the bar were much in use by the delegates, who did not pay cash but merely signed chits.

CONFERENCES BEGUN NOV. 22

At 11 A.M. on Nov. 22, the conference began. Gen. George C. Marshall entered the central lobby. Shortly thereafter, papers and pencils were rushed into Conference Room No. 1 and soon the military chiefs entered the chamber. A little later Lieut. Gen. Joseph Stilwell came up and asked where Conference Room No. 4 was. At 3 P.M. a general conference began, after the staff talks, the OWI official said.

The Cairo Conference, in 1943. From left, Chiang Kai-shek, Roosevelt, Churchill and Mme. Chiang Kai-shek.

At this point the correspondents rushed in with a series of questions regarding the details and color surrounding the meeting. The following unrelated facts emerged:

On Sunday night, Nov. 21, General Chiang called on Mr. Churchill and at 11 A.M. the next day the Prime Minister called on Mr. Roosevelt.

The entire ground floor of the hotel was devoted to conference rooms, of which there were five. There were offices on the first, second and third floors. About eighty offices were prepared in advance.

Maps posted in the main corridors listed the offices. Special telephone directories and exchanges were prepared, each national delegation having its own differently colored directory.

The British Government acted as host for the conference, footing all the bills. The preliminary arrangements for this meeting began some time ago, with about twenty specially sworn officers and more than 200 soldiers making preparations.

Outside the hotel, in the garden, British medical and dental posts were erected in special tents with tiled floors. Serious medical cases would have been sent off immediately by ambulance to the Fifteenth General Hospital.

The first call on the medical officers was made by Mme. Chiang shortly after her arrival on Sunday. She had her own doctor with her, but was bothered by serious eye trouble and her face was swollen. After a consultation between a conference medical officer and the Chinese doctor, specialists were called and Mme. Chiang was treated for a painful, but not serious, illness.

A special deep air-raid shelter and many slit-trenches were built around the hotel and the villas.

The make-up of the British delegation was announced after these details had been given. Mr. Churchill brought, as his aide-de-camp in his capacity of Minister of Defense, his daughter, Section Officer Sarah Oliver of the Waaf, the wife of the well-known comedian.

His party included Lord Moran, president of the Royal College of Physicians, as his doctor; Comdr. C.V.R. Thompson, his personal assistant, and two private secretaries.

On Monday, after his call on Mr. Roosevelt, Mr. Churchill repaid a call by General Chiang at noon in the latter’s villa.

At 3 P.M. on Monday the first big meeting in Conference Room No. 1 commenced. British marine guards were posted at each door.

The room looks out on a path leading to the hotel’s drained swimming pool, which was also blocked off and guarded.

British, American and Chinese delegates attended the session. They included the service chiefs of all three nations. The sitting lasted one hour.

The British delegation’s offices were on the first floor, the Americans’ on the second.

On Monday afternoon the hotel was like a railway station. World-important figures were milling about, shouting “Hello, how are you? I haven’t seen you for a long time.” Numerous beribboned generals were moving around in clusters.

As one American observer put it, the interior of the conference room was very depressing and filled with gaudy furniture. The lobby was like a college-town hotel during a class reunion.

On Nov. 23, two conferences took place in the hotel. A British staff meeting occurred between 9:45 A.M. and 12:30 P.M. and an American counterpart lasted from 11 A. M. to 12:30 P.M. This, it was explained, was the normal procedure for staff talks.

On Sunday evening, according to later disclosures, Mr. Churchill had all the British staff chiefs to dinner in his villa, and informal talks followed. On Monday morning he conferred with Sir Archibald Clark-Kerr, Ambassador to Russia, then called on Mr. Roosevelt and General Chiang. Gen. Carton de Wiart was present at the latter call. Mr. Churchill lunched privately with Mr. Roosevelt at the latter’s villa, rested during the afternoon and then dined with him. After dinner the two statesmen held a discussion with their military staffs. No Chinese were present. The Prime Minister returned to his villa with the British chiefs and worked until 2 A.M.

On Tuesday morning a plenary conference was held among the political chiefs at President Roosevelt’s villa. Chinese representatives attended. Mr. Churchill and Mr. Roosevelt again lunched together.

During the conference Mr. Churchill and Mr. Roosevelt visited the Pyramids. Mr. Roosevelt sat in a large brown car while Mr. Churchill, his daughter and staff walked about at the base of the Sphinx.

The statesmen remained a half hour. As the sun began to set in the western desert they moved on to a point from which the Pyramids could best be viewed with security. Officers rattled behind on jeeps and a few British antiaircraft gunners manning the nearby defenses gazed on in awe.

IMPORTANT TALK ON ASIA

On the afternoon of Nov. 23 an important conference concerning Allied strategy in Asia was held. At 3:20 P.M. word ran through the hotel that General Chiang was coming. Large colored maps of Asia were placed on the walls of the conference rooms and place-cards were affixed to the green table.

General Chiang was placed at the north end and Admiral the Lord Louis Mountbatten at the south, with various generals and admirals between. The Chinese were all handsomely uniformed and included China’s only admiral, C. S. Yang.

This key talk began at 3:30 P.M. and ended a half hour later when the delegates, preceded by Admiral Leahy, emerged with earnest, grim expressions. Admiral Leahy led a group of high officials upstairs with Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault to the American secretariat, while five Chinese officers waited in the lobby.

The arrival of Ambassador Laurence A. Steinhardt indicated that Turkey’s position would be reviewed.

On the morning of Nov. 24 three important meetings took place:

The British staff chiefs met in Room 1 for an hour, other British experts met for a short time in Room 5, and all morning long the American chiefs of staff as well as some Chinese conferred in Room 4.

The delegates were working excessively hard by midweek. There was much shuttling about, with sixty-four jeeps making more than 150 trips daily. By Wednesday evening it was established that Mr. Roosevelt, Mr. Churchill, General Chiang and their staff chiefs were in constant daily contact. General and Mme. Chiang saw Mr. Roosevelt on Nov. 22 and dined at his villa the next evening. General Marshall had dinner alone with Mr. Churchill on Nov. 23.

At 11 A.M. on Wednesday a plenary conference was held in Mr. Roosevelt’s villa among the Government chiefs and their staffs. The President lunched with Mr. Churchill afterward.

By the morning of Nov. 25 a galaxy of famous Allied figures had appeared. Virtually every famous United Nations military leader was here.

Dr. Tong revealed details of General Chiang’s daily routine, pointing out that it was unchanged by the African atmosphere and the press of new work. The Generalissimo rises at 5 A.M. and spends a half hour at his devotions. After breakfast he starts his work.

Both Generalissimo and Mme. Chiang atended the plenary conferences with the heads of states, where Madame Chiang interpreted for her husband. But neither attended the strategic staff talks.

General Shan Chen, director general of National Military Council, represented China as senior military officer, with Admiral Yang as chief of intelligence, since the only navy that he has is Yangtze River gunboats. Gen. Shih Ming, military attaché in Washington, acted as interpreter.

On the evening of Nov. 24 there were new arrivals. Harold Macmillan, British member of the Italian Advisory Council, flew in. Then Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden arrived with Sir Alexander Cadogan.

EISENHOWER AND MURPHY ATTEND

On Nov. 25, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Robert D. Murphy arrived. This indicated obvious preparations to include European aspects in what had hitherto been primarily Asiatic talks.

Although Thursday was Thanksgiving, the conferences continued, with two American talks in the morning as well as one British staff talk. But during the afternoon the conferences were largely limited to lesser officers. A new world map was placed in the main meeting room.

On Thanksgiving Day, General Eisenhower received the Legion of Merit from Mr. Roosevelt at his villa before General Marshall. The award was made for his “outstanding contributions to the Allied cause.” Mr. Roosevelt dined the previous night with Mr. Churchill, Mr. Eden, Mr. Hopkins, W. Averill Harriman, Mr. Winant, Col. Elliott Roosevelt, Maj. John Boettiger and others.

All during Nov. 26, Mr. Eden worked steadily, conferring often with Mr. Winant and lunching with several Allied dignitaries. In the afternoon, in Conference Room 1, there was an important meeting of the staff chiefs and the Mediterranean commanders. After an hour the Mediterranean experts left but the conference continued.

After some time the most secret talks, among staff chiefs only, commenced. All others left the room and the Marine Guards were ordered to permit no entries, regardless of rank.

1,026 MARINES LOST IN TARAWA CAPTURE

2,557 Wounded, Nimitz Reveals—65 Soldiers Died On Makin, 121 Injured In Assault

ONE SLAIN ON ABEMAMA

Our Total Casualties Of 3,772 Compare With Japanese Dead Numbering 5,700

By GEORGE F. HORNE

By Telephone to The New York Times.

PEARL HARBOR, Dec. 1 —Our total casualties among assault forces in the Gilberts occupation numbered 3,772 men.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commanding the United States Fleet and Pacific Ocean areas, in a communiqué issued before noon today, listed total casualties on the basis of preliminary reports that have come in from Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commander of the Central Pacific force; Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith, USA, commanding the Twenty-seventh Division, elements of which made the landing on Makin, and Maj. Gen. Julian Smith, United States Marine Corps, commanding the Second Marine Division, which took Tarawa.

The aftermath of the Battle of Tarawa.

The figures reveal that at Tarawa 1,026 men were killed in action and 2,557 wounded; at Makin sixty-five were killed in action and 121 wounded, and at Abemama one was killed in action and two were wounded.

The figures noted in the communiqué are approximate and cover events up to today. Final and conclusive reports, which will take some time in preparation, are not expected to vary greatly from these estimates, which have been released with unusual promptness following the termination of the engagement.

WARNINGS RECALLED

In the light of stern warnings issued in high quarters here and in Washington and equally in view of the tremendous value that will accrue to us in possession of the islands, the losses are not considered too extreme.

The losses might well have been much higher, considering the surprising strength of the Japanese defenses at Tarawa, and they may be compared favorably with Japanese losses. In assault operations of this kind it is almost invariably the case that the attacking troops lose more than the defenders. Tarawa was taken by less than a division of marines, against about 4,500 Japanese defenders, of whom approximately 3,500 were fighting men and the rest laborers.

At Makin there were fewer than 1,000 Japanese. The assault there took fifty-four hours. Landings on Abemama, which took place after the other battles were well under way, met virtually no resistance and the marine raider force cleaned up the island in a matter of a few hours. Abemama was defended by fewer than 200 men.

The figures released today include a few Navy and Coast Guard casualties among the men of these elements who engaged in the landings as part of the medical forces and landing boat crews.

Against our losses it is now possible to set fairly accurate figures of Japanese losses. We all but wiped out the garrisons of the enemy on these islands, for few prisoners were taken. Including the laborer-prisoners mentioned in the over-all figures, the Japanese had approximately 5,700 men on the three atoll groups.

In the absence of any indication of severe losses among our sea forces—and Secretary of Navy Frank Knox has been quoted in Washington to the effect that they were “light”—it is fair to compare our total killed in action—1,092—with the total Japanese strength of 5,700.

No attempt is made in the comparison to gloss the rugged truth. Admiral Nimitz, in his stark communiqué says merely, “Preliminary reports of the Gilbert operations indicate that our landing forces suffered the following approximate casualties,” and then comes the table.

A few remaining enemy stragglers in the north of Tarawa atoll were mentioned two days ago. There are no more now. The last sniper has been ferreted out and the last foxhole purged. No Japanese are left in the Gilberts.

2 CARRIERS SUNK, FOE CLAIMS