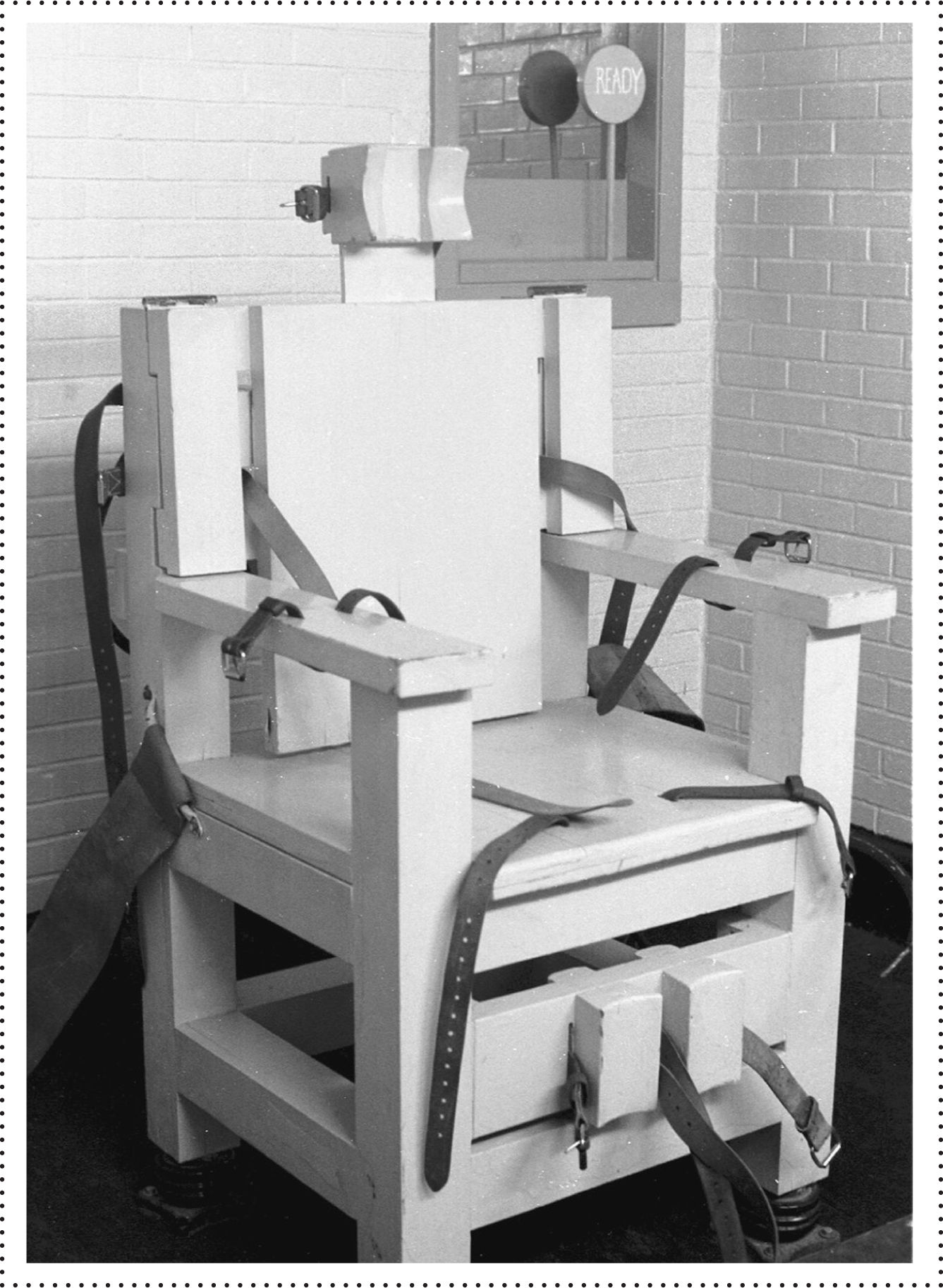

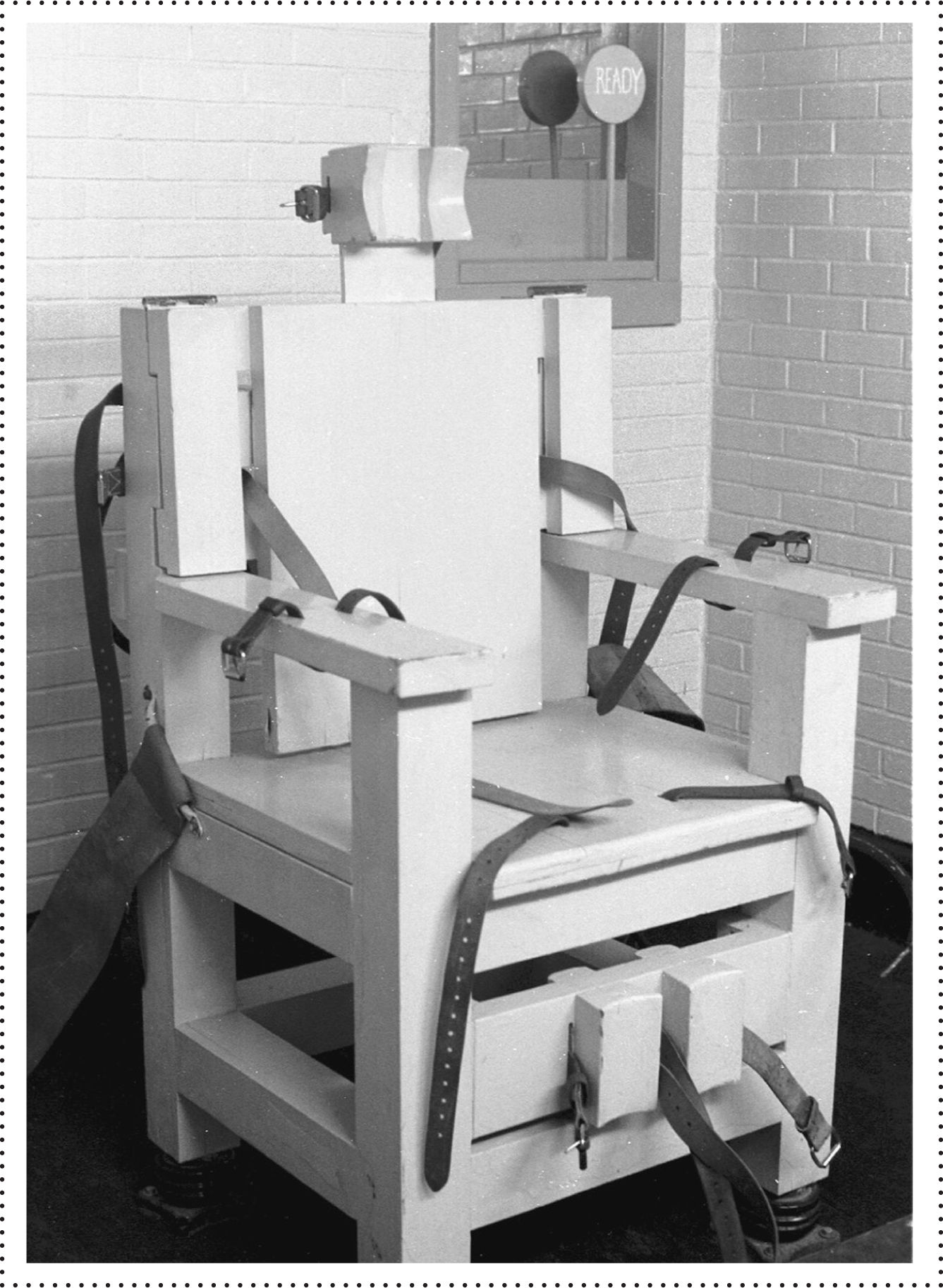

Alabama’s electric chair, dubbed “Big Yellow Mama.”

IN LOUISIANA, THEY called it “Gruesome Gertie.” Tennessee officials named theirs “Old Smokey.” Several states, including Georgia and Florida, used the moniker “Old Sparky.” Other states dubbed the electric chair “Sizzlin’ Sally.” After Alabama prison officials painted theirs with five gallons of shocking, reflective-yellow, center-stripe road paint, someone said, “That’s one big yellow mama.” The name stuck. Since it was first used on convicted murderer Horace DeVaughn in April 1927, some 144 inmates—121 black, 24 white—had died in “Big Yellow Mama” by the time Caliph Washington arrived on death row in the late 1950s. Alabama law was clear on the matter: a convict sentenced to death would be killed by electricity of “sufficient intensity.”

First introduced in New York in 1890, the electric chair was seen as a humane and modern alternative to hanging in an era driven by new technologies and a progressive impulse to reform. Over thirty-five years later, when Alabama changed from hangings to electrocutions as the favored method of state-performed executions, Kilby warden T. J. Shirley promised Ed Mason furlough or perhaps a parole if he built the state’s electric chair. A native of London, England, the forty-two-year-old Mason was serving a lengthy sentence for burglarizing six homes in Mobile to pay off his gambling debts. “I had lost a large sum on the races in New Orleans,” he told a reporter in 1927. “It was a sort of gambling fever that had me, I guess, but I never harmed anyone bodily and never intended doing anyone bodily harm.” A master carpenter, Mason arrived at Kilby soon after the prison opened its doors in 1923 and spent his days building cabinets, desks, cradles, and caskets. In November 1926 he selected several giant pieces of wood from a maple tree and set about crafting the state’s instrument of death in the prison’s woodworking shop. As he worked, he gave the chair little thought. “Every stroke of the saw meant liberty to me,” he later said, “and the fact that it would aid in bringing death to others just didn’t occur to me.” But those working in the shop with Mason understood the purpose of the big maple chair. “I’ve called on each one to help me,” he said at the time, “and each one refused to touch the chair.”

But as Mason completed his task, an overwhelming sense of hopelessness enveloped him. “This is my first electric chair,” he lamented, “and if I were called upon to make another I’d flatly refuse and pay the penalty. Whatever it might be, it could be no worse than a troubled conscience.” The squat, stiff-backed electric chair stood four feet, five inches tall and weighed 150 pounds. It had smooth flat armrests, a sliding back, and an adjustable headrest—like a barber chair for a man the size of Jack’s giant. The master carpenter also fitted the chair with heavy leather straps for securing the doomed inmate. Mason finished the project in six weeks and named the unadorned smooth-sanded chair “Plain Bill,” after Alabama’s sawed-off, five-foot-one governor, W. W. “Plain Bill” Brandon—a man of quiet generosity who handed out paroles like Bible tracts. Everyone deserved a second chance, he believed, and to blunt criticism of his leniency, he often quoted the motto of the Salvation Army: “A man may be down, but he is never out.” Nevertheless, when Brandon left office in early 1927, Mason found himself still in, and not out. “Plain Bill” forgot to grant Mason’s free time. In response, the irritated prisoner changed the name of his chair to “Plain Bull.” When he finally received his furlough from Governor Bibb Graves, Mason left the state and was never heard from again, despite efforts to locate him.

Mason completed only the woodwork on the chair—the job of wiring fell to state engineer Harry C. Norman. Norman, having never tackled a project of this sort, traveled to neighboring states to see how other electric chairs were designed and wired. The architect of Florida’s chair told Norman to keep it simple: “The desired process of electrocution requires that a sufficient voltage be applied to cause instant death with the least burning.” Alabama’s engineer drew up plans for the chair with semiautomatic controls; once the switch was thrown, a prisoner would get a first fist-clinching jolt of power; the current would then reduce and automatically build back up to 2,250 volts for a second shot of electricity.

On April 8, 1927, Horace DeVaughn, convicted of murdering two lovers on a lonely road near Birmingham, would be the first to test Mason’s and Norman’s handiwork. Engineer Norman knew so much about the workings of his device that prison officials tapped him to apply the electrodes to the condemned prisoner. After the prisoner sat in the chair and guards secured him with the leather straps, Norman was to take a sponge, which had soaked for almost two days in a saltwater solution, and fit it inside a band he made of screen wire and a few strips of brass. He would then place this atop the condemned person’s head and strap it around the chin. This flexible but snug-fitting crown would prevent the flesh from burning and allow for good conduction. Norman would repeat the same process on a smaller band that would attach to the lower left leg. He would then connect the electrodes and create an electrical current between the head and leg. Norman, however, quit the job just days before DeVaughn’s date with the chair. “A few nightmares persuaded me,” Norman later recalled, “to quit the prison post” because he didn’t like the “idea of electricity shooting through a man.” DeVaughn didn’t like it much either when novice prison officials turned the juice on over and over again, four shots in all, to get the inmate well done and well dead.

The history of electrocution in the United States was characterized by, as Supreme Court Justice William Brennan wrote years later, “repeated failures” to kill the prisoner on the first try. It was “difficult to imagine how such procedures constitute anything less than ‘death by installments’—a form of torture [that] would rival that of burning at the stake.” Evidence suggested, Brennan argued, that death by electrocution was a violent, inhumane, and painful indignity “far beyond the mere extinguishment of life.” When the switch was thrown, eyewitnesses reported, the doomed criminal would lurch, cringe, leap, or “fight the straps with amazing strength.” At times the blazing electrical current would pop a prisoner’s eyeballs out of their sockets like a cork from a champagne bottle; their stomach, bladder, and bowels would empty all contents; their body would contort and twist as their skin turned red, swelled, and stretched “to the point of breaking”; the sizzling sounds and pungent smells of bacon frying in a cast-iron skillet filled the room of death as the condemned convict’s body would boil on the inside and fry on the outside.

By the 1930s and 1940s, electrocutions in Alabama soon became so routine, as one Kilby warden recalled, that it was just part of a “good day’s work” to pull the switch and send a lightning strike into a prisoner’s body. With “neatness and dispatch,” a trained crew of prison officials administered Alabama justice with quick efficiency. “A five-year-old child could pull the switch,” a Kilby official believed. The switch started a generator, which built up power until it sent the two shocks—ninety seconds apart—into the condemned man. “Unconsciousness comes in the flicker of an eye,” warden Frank Boswell said, “and death in a flash.”

State law mandated that the Kilby warden (or his appointed representative) turn on the electrical current at exactly 12:01 a.m. on Fridays. On February 9, 1934, Boswell and his crew electrocuted five black men—Bennie Foster, John Thompson, Harie White, Ernest Waller, and Solomon Roper—all within thirty minutes. In 1936, the chair saw its most yearly activity, with seventeen individuals meeting death. Kilby’s warden, wrote one newspaper reporter, “has known sorrow, pity, regret, horror, spent wakeful nights over his job, but through it all has felt that it was a good job well done and that justice has been carried out for the good of humanity.”

Year after year, men, and a few women, took the final thirteen steps from the holding cell (what prison officials called the Bible Room), through a small green door, and into a cramped gray room where the electric chair waited. The tiny death parade—the “ghostly train,” as one writer described it—moved slowly along the narrow corridor with the prisoner flanked by the prison chaplain and often a Salvation Army captain. Arm in arm, the three repeated the Twenty-third Psalm (“Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil”) as they inched closer to the green door. When the door to the “room of no return” opened, most prisoners closed their eyes to avoid gazing upon the instrument of their death. “I’ve never seen one who didn’t,” remembered a Kilby guard. The guards inside the chamber led the prisoner into the arms of the death chair.

Most accepted the inevitability of the end and remained calm and composed. “It’s amazing how well the majority of the condemned people take it,” one warden said. “Most of them want to go braver than the one before him.” When the guards stepped clear, the room grew quiet. The chaplain often repeated Psalm 23. Many times, the prisoner repeated the words or moved his lips in silent recitation. As the guards began attaching the electrodes, sometimes either the prisoner, the chaplain, or both, said a brief prayer.

During the 1930s and 1940s, warden Frank Boswell trusted no one but himself to handle the sponges—if they were too dry, then not enough current passed through the body; too wet, and the current burned the muscles. “So I stay in front, dampen my own sponges, and carefully superintend the strapping of the condemned in the chair,” Boswell once said.

With the sponge work and the wiring completed, the warden then asked if the condemned prisoner had any last words. Most did not. A few gave final statements. “I believe the Lord hath forgiven all of my sins,” declared Clarence Hardy before his death in 1942. “I ask all the people to forgive me. I am satisfied of going to heaven and hope that all of you people will meet me there.” Some condemned men were never repentant. Elbert J. Burns, who was strapped in the chair four years after Hardy, told all present that he hoped “everyone who had anything to do with executing me goes to hell.” With his last words, a black hood was draped over his head. One newspaper reporter remembered that, when the guards covered the prisoner’s face, he seemed to no longer be a human being: “He looked like an animal with that thing over his head.” With everything connected, a prison official then picked up a wooden paddle with “Ready” carved on one side and held it up to the small glass window between the death chamber and the control room. Unless a last-second reprieve from the governor or a higher court arrived to spare the prisoner’s life, all options had run out. Someone threw the switch.

IN NOVEMBER 1959, Caliph Washington and the rest of Alabama’s black, circuit-riding death row inmates returned to Kilby Prison for the December 4 execution of one of their little group, Ernest Cornell Walker. Walker, convicted of raping a white woman in Homewood, Alabama, pleaded for his life in front of Governor John Patterson on December 2. “I know now that I did wrong and I’m sorry,” he told the governor. Patterson showed no mercy, even though attorneys contended that Walker was mentally incompetent and had the intelligence of a child. Throughout much of the next day, he sat on the edge of the bed in the Bible Room and wept inconsolably. That evening he refused his last supper and spent his last few hours reading a Bible and visiting with Kilby chaplain R. S. Watson—he soon professed his faith in Jesus Christ to the soft-spoken minister. Just before the solemn hour of midnight, Walker showed no emotion as he walked the final steps to the death chamber to “ride the lightning.” As guards strapped him in the chair, he told Watson, “Thanks, Reverend.” He then spoke his last words: “Jesus has saved me.” For a moment, the entire prison seemed quiet. Nearby, Caliph Washington and the other death row inmates watched, listened, and waited.

When the executioner threw the switch, the dull sound of the generator began building, and the horrific noise of death echoed throughout the cellblock. The generator was separate from the prison’s main power system, so when the current built to its climax, the lights in the building continued to burn bright. The dimming of the lights during an execution was what was on “television and in the movies,” one guard said, and it was not the reality in Kilby. Nonetheless, at 12:14 a.m., two physicians pronounced Walker dead.

One week later, a white inmate, Edwin Ray Dockery, went to the chair still proclaiming his innocence. “Look, I never for one minute denied that I killed a man,” Dockery explained. “I got a bum rap on this deal. I claim it was self-defense, but the jury convicted me of murder. There was nobody there but the two of us. I’m alive and he is dead. Nobody believes me.” But unlike Caliph Washington, who also pleaded self-defense, Dockery had a long record of crime and violent behavior before his conviction in the murder of Willie T. Heatherly in 1958. “I’ve been in trouble since I was fourteen and I guess this more or less evens things up. I lived as a burglar. I have robbed people. Twice I escaped from prison. Sooner or later things catch up with you, and that’s why I’m here in Kilby now.”

Kilby prison officials allowed condemned inmates an opportunity to order a final meal of their choosing. Most refused. Dockery, however, ordered a dozen oysters, a dozen shrimp, two veal cutlets, a salad, six buttered rolls, half a banana pie, ice cream, and expensive cigars. Once he finished his last supper, he lit a cigar and visited with Father William Wiggins, a Roman Catholic priest, and Reverend Tilford Junkins, one of Alabama’s most prominent Southern Baptist evangelists. After listening to the salvation plan from both theological perspectives, the inmate converted to Catholicism—most likely to the chagrin of the Baptist preacher. Just before midnight, Dockery walked to the death chamber, flanked by Wiggins and Junkins. He smiled as he sat in the chair and told the onlookers “I am not guilty of first degree murder.” By 12:10 a.m., he was dead. As the warden removed the black hood, Dockery still wore a smile.

Columbus Boggs was on Alabama’s death row for murder. During the summer of 1957, Boggs escaped the Etowah County Jail in east Alabama, where he was being held on charges of assault and attempted robbery. He stole a truck and went on a statewide crime spree—heisting cars, robbing businesses, and stealing weapons. While crisscrossing Alabama, Boggs stopped in Uniontown, near Selma, and robbed a small grocery store and murdered the elderly owner for $80. An all-white jury in Dallas County deliberated sixty minutes before declaring him guilty, and the judge sentenced him to death. Four months after Dockery’s electrocution on April 29, 1961, Columbus Boggs died in the electric chair.

UNLESS THE ALABAMA Supreme Court overturned his conviction, Caliph Washington would someday meet the same fate. He waited for the high court’s decision as days turned into weeks, weeks into months, and months into years. No word came. He passed his time like many other death row inmates: sleeping, reading, praying, thinking, and fighting. By the early 1960s, Alabama prison officials stopped moving the black inmates back and forth from Atmore and packed in as many as four prisoners per cell on Kilby’s death row.

In September 1961, Caliph Washington was sharing cell space with three black men, Willie Seals, Jr., Drewey Aaron, and Charles Hamilton. Seals and Aaron earned spots on Alabama’s death row for raping white women, and Hamilton for burglary with the “intent to ravish.” One afternoon, as guard B. G. Weldon walked along the corridor just outside the death row cells, he noticed blood covering Hamilton’s shirt. Following an investigation, Lieutenant W. L. Trawick learned that Seals and Aaron beat Hamilton over the head repeatedly with their fists, while Washington cheered them on. “The subject was shouting,” Trawick wrote in a report to the disciplinary board, “and encouraging other inmates to attack Hamilton.” Caliph Washington, he added, “was one of the main instigators of the fracas,” although he never hit anyone. The Kilby disciplinary board, which included warden Martin J. Wiman, assistant warden William C. Holman, and classification officer Marlin C. Barton, reviewed the report and ordered Washington and the others to spend twenty-one days in one of the airless solitary confinement cells. Guards ordered Washington to strip down to his shorts and nothing more for his stay in the hole.

On September 9, 1961, they led the inmate down the stairs to cell number five, opened the door, handed him a slop bucket, and pushed him inside. For days, Caliph Washington sat on the stone cold floor with no mattress, cot, or blanket. The only time he left the cell was to empty his slop bucket in a nearby toilet. “His is a life without sunrise or sunset,” one reporter noted, “and things like rain or blue sky matter not at all because it is always black in his four walls of steel; and chilly and uncomfortable, too, because there’s nothing in there with him but a small container for a latrine.” His only visitor was the guard who stopped by three times a day to feed him a “non-palatable” diet of bread and water and listen to his complaints. Caliph liked to talk, and this was his chance each day to communicate with another human being. Otherwise he sat in the silent darkness. After only a week, prison officials let Caliph out of the hole and returned him to his cell on death row.

A few weeks later, on November 24, 1961—the day after Thanksgiving—another black death row inmate, Joe Henry Johnson, became the first person executed in the state’s electric chair since Boggs’s death some seventeen months before. In January 1960, an all-white jury in northern Alabama convicted Johnson of the savage beating deaths of two women in Atmore, near the Tennessee border. According to trial testimony, Dicie Boyd caught seventeen-year-old Joe Henry in her barn engaged in sexual activity with her milking cow. To hide his bestial sin, Johnson raped and murdered the sixty-two-year-old Miss Dicie, and then bludgeoned to death her eighty-nine-year-old mother, Rowena Boyd. “May God have mercy on me and be with me” were Johnson’s last words.

By Christmas 1961, Caliph had waited two full years for some word from the Alabama Supreme Court. None came. He slipped deeper into a dark, quiet despair. In February 1962 he earned a fresh trip to the hole for “exchanging personal possessions and papers” with other inmates and “publicly criticizing rules and regulations of the holding unit.” The disciplinary board also punished Thomas Stain, Roosevelt Howard, Drewey Aaron, Willie Seals, William Bowen, and Wilmon Gosa. In August of that year, Gosa, who was convicted of murdering his five-year-old daughter with a butcher’s knife, made no final statement before he was strapped in the chair and put to death.

As 1962 was nearing an end, Caliph Washington awaited word on his appeal. The case was being heard by the Simpson division of the Alabama Supreme Court, led by the fifty-nine-year-old associate justice, Robert Tennent Simpson. A native of the northern Alabama hamlet of Florence, Simpson earned his law degree from the University of Alabama in 1917—just as America was entering the Great War. Simpson soon joined the army and saw action in France during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, where he earned a Silver Star for bravery. After the war, he practiced law, served as a circuit solicitor, and sat on the bench of the court of appeals. Alabama voters elected him to the state supreme court in 1944.

In 1962, the other members of the Simpson division included John Lancaster Goodwyn, a Montgomery native who served on the bench since 1951, and James Samuel Coleman, Jr., of Eutaw, who was elected to the court in 1957. During the discussion of Washington’s appeal, the justices divided over the decision, making it necessary for the entire court to hear the case in general conference. Chief Justice Ed Livingston prepared the majority opinion. Born in 1892 in the Black Belt community of Notasulga, Alabama, Livingston earned his law degree at the University of Alabama in 1918. His homespun humor and storytelling ability served him well during his twenty years as a practicing attorney in Tuscaloosa and as a part-time law school instructor. He drove a rusty, oil-burning, ramshackle Ford around town with a host of missing parts, including the license plate. Once while rambling through Bessemer, a motorcycle policeman pulled him over for driving without an automobile tag. When the officer asked why, Livingston said, “Mr. Officer, I could tell you a cock and bull story which you probably would not believe, so I will tell you the truth. I am a teacher in the law school in Tuscaloosa, and one of my students is the license inspector, and I am riding the hell out of the situation.”

In 1940, he rode his popularity to election as an associate justice of the Alabama Supreme Court. In 1951, Governor Gordon Persons appointed “Judge Ed” as chief justice, where he reminded young attorneys that the practice of law was a privilege and not a right. Still, his deep respect for the law and his keen legal mind never transcended his Black Belt racial views. When the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the Brown decision, Livingston attacked it for attempting to take over local governments by writing opinions, not laws. “I have nothing but reverence for the Supreme Court as an institution,” he said, “but that’s as far as it goes.” By the late 1950s, like many white southerners, Livingston became more reactionary in his support of segregated schools. “I would close every school from the highest to the lowest before I would go to school with colored people,” he emphasized. “I’m for segregation in every phase of life, and I don’t care who knows.” The justice was “riding the hell” out of the racial situation.

Still, in the Caliph Washington case, Furman Jones’s testimony, and not race, was the key issue. On October 4, 1962, Alabama’s high court handed down its decision in Caliph Washington v. State of Alabama. The focus of the appeal was based on the admissibility of Furman Jones’s testimony from the first trial. “It is a well-settled rule in Alabama,” Livingston argued, “that when a witness is a nonresident, or has removed from the state permanently or for an indefinite time, his sworn testimony taken on any previous trial for the same offense may be offered in a subsequent trial if a proper predicate is laid.” If the proper foundation (predicate) was never provided, then prior testimony of the witness was inadmissible.

Livingston, however, argued that circuit solicitor Howard Sullinger provided the background necessary for offering Jones’s testimony. The prosecution proved, through evidence and testimony, that Furman Jones’s address was Box 465, Jonesville, South Carolina, and that a deputy sheriff sent a subpoena to the address. The chief justice added: “The sufficiency of a predicate for the introduction of testimony given by a witness on a former trial is addressed to the trial court’s sound discretion.” In conclusion, Livingston emphasized that the evidence in the Caliph Washington case was clear and sufficient to “justify the verdict reached by the jury. . . . The Court has carefully examined the record, as is our duty under the automatic appeal statute, supra, and find no error to reverse.” Justices Simpson, Goodwyn, Merrill, and Harwood concurred with Livingston’s opinion.

Justice Coleman, however, dissented. He argued that the prosecution failed to provide a proper predicate for the admission of Furman Jones’s testimony from the first trial. “I am of the opinion,” he wrote, “that the court erred in allowing his testimony to be admitted. . . . As I understand the opinion of the majority, they hold that Jones’ former testimony laid its own proper predicate. I, therefore, respectfully dissent.”

With the conviction confirmed, Caliph Washington’s execution date was set for Friday, December 7, 1962. His attorneys, however, filed an application for rehearing on October 19, and the court once again stayed the date of execution pending the ruling. On January 17, the Alabama Supreme Court denied the application and set the execution date of Friday, March 29, 1963.

ATTORNEYS KERMIT EDWARDS, David Hood, and Orzell Billingsley all left the case following the high court’s decision. They were replaced by two white Birmingham lawyers, Robert Morel Montgomery and Fred Blanton, Jr. Dashing, patrician, flamboyant, and supremely self-confident, Morel Montgomery was a specialist in criminal defense and one of the city’s best trial lawyers. By 1964, he had practiced law for forty years and never had a client executed. “He tried hundreds of capital cases,” his son once said, “and never lost anyone to the electric chair. That was some accomplishment.”

But for Morel, these cases were less about saving a life than about boosting his ego and receiving more notoriety. He thrived on high-profile capital murder cases like Caliph Washington’s and once boasted, “If you want to change things in this world, keep your name in the news-paper, be the news good or bad.” Morel Montgomery’s name was frequently in the local papers for both his brilliant legal victories and his unseemly underworld clientele. He provided legal representation for a southeastern liquor syndicate controlled by Chicago mobster Al Capone and was once indicted for “violating or conspiring to violate” internal revenue laws governing illegal whiskey. Montgomery also received a two-year suspension by the Alabama Bar Association following a bribery charge.

In contrast, the handsome cigar-smoking Fred Blanton championed the lost causes of underdogs in appellate cases. “I always want to do my duty for indigent defendants who need representation,” Blanton once wrote, “and I welcome assistance from whatever source available.”

Even with the hardworking and compassionate duo of Montgomery and Blanton on his case, Caliph Washington was running out of options. As his clemency hearing approached, he found himself sinking deeper into the darkness of despair. Most condemned men expected nothing good to come from the hearing, and Caliph was losing all hope. One day as he sat on his bunk, a preacher walked by and asked him what he was “crawled up in a hull about?” Washington glared at the minister and snapped, “How would you feel if you were fixing to die in a couple of weeks?” The minister could see the depression and desperation on Caliph’s face. “The impact of having to die doesn’t sink in until . . . before your clemency hearing,” Washington continued. “It’s pretty hard to pretend that you’re going to live on when down in your heart you know that you will have to die. That you will be executed.”

Two weeks prior to the clemency hearing, on March 5, a tornado roared through Bessemer like a runaway freight train, destroying or damaging more than one hundred homes and businesses. “It is fantastic,” Mayor Jess Lanier said, “that no one was killed.” That same day, down the road in Kilby Prison, Caliph Washington’s hopelessness turned to storming rage, and he lashed out at inmate Robert Swain, a twenty-two-year-old black man who was on death row for raping a white woman in Talladega. The bloody fistfight with Swain earned Washington another twenty-one-day trip to the hole. In this dark room he would wait for his clemency hearing.

Unknown to Washington, a lone glimmer of hope emerged from a most unlikely source: Alabama’s new governor, George Wallace. Following his stinging defeat to the race-baiting John Patterson in 1958, the politically opportunistic Wallace vowed to supporters that “no other son-of-a-bitch will out nigger me again.” He returned to his work as a circuit judge for Barbour and Bullock Counties and forced a confrontation with the U.S. Civil Rights Commission over voting records from his circuit.

When he refused to hand over the materials, Federal Judge Frank Johnson held Wallace in contempt for defying the commission. Rather than face jail time, the manipulative Wallace quietly turned over the records to a grand jury and they passed them to the commission, allowing Wallace to brag about defying the federal government. “This empty but symbolic gesture,” historian Glenn Eskew wrote, “appealed to many Alabama voters, who saw meaning in the resistance to federal encroachment.” Keeping true to his pledge, Wallace resorted to racial demagoguery throughout his 1962 campaign, blasted the federal government for encroaching on states’ rights, and vowed to “stand in the schoolhouse door” to stop integration. “He is a fighter,” Wallace supporter and Bessemer mayor Jess Lanier proclaimed, “and our state loves a fighter.” He won in a landslide.

In January 1963, Wallace took the oath of office for his first term as the state’s chief executive and promised in his inaugural speech to maintain segregation in Alabama now, tomorrow, and forever. If Wallace was willing to compromise most of his core principles for political expediency, he also remained, however, morally opposed to the death penalty. “I, like many other governors before me,” he said in 1963, “wish this cup would pass from me.” He loathed the “terrible burden” of this “solemn and awesome” power to choose life or death for another human. “Any governor would dread this duty and responsibility,” he wrote. “But it’s something the governor has got to face under the law.” This was one of the most serious obligations of his office, he emphasized. “No decision is made without much time, effort and study devoted to the decision. . . . You may be sure that this matter causes me to lose much sleep and I have given prayerful consideration to every case involved.”

Those who worked closely with Wallace during these years believed the governor had, at the least, serious reservations about the use of the death penalty. Albert Brewer, a key Wallace supporter in the Alabama House of Representatives, recalled that the issue caused the governor great consternation. “He simply did not want someone executed at the hands of the state,” Brewer emphasized. Wallace’s personal lawyer, Maury Smith, was more direct. “I believe he was opposed to the death penalty,” Smith said. “He was a very sensitive man and easy to appeal to. . . . That really was his nature.” State legal adviser Hugh Maddox agreed: “Most people would be quite surprised at Wallace’s true feelings on the death penalty.”

Each previous Alabama governor sent a long line of prisoners to their death in the state’s electric chair. Between 1927 and 1963, on average, Alabama governors allowed almost seventeen executions per four-year term. The highest number of electrocutions, thirty-two, occurred during the term of Frank Dixon between 1939 and 1942. The lowest number was four during James Folsom’s second term from 1955 to 1959. John Patterson, George Wallace’s predecessor, approved five executions between 1959 and 1962.

While wrestling with the moral dilemma of capital punishment, Wallace decided to postpone all Alabama executions. For Caliph Washington, and the seven others waiting for death, having George Wallace occupying the governor’s office saved their lives. Beginning on March 22, 1963, just one week prior to the scheduled execution, Wallace issued a reprieve for Washington. The formal citation bore the state’s seal and began with the antiquated salutation: “In the Name and by the Authority of the State of Alabama, I, George C. Wallace, Governor of the State of Alabama; To all Sheriffs, Keepers of Prisoners, Civil Magistrates and others to whom these presents shall come—GREETINGS.” The document reviewed Washington’s conviction of first-degree murder and his sentence of death, to be carried out on March 29, 1963. “And Whereas,” it continued, “for divers good and sufficient reasons it appears to me that the said Caliph Washington should be granted a reprieve. Now, Therefore, I George C. Wallace, Governor of the State of Alabama, by virtue of the power and authority in me vested by the Constitution and laws of the State of Alabama, do by these present, order that reprieve be and it is hereby granted to Caliph Washington until Friday, June 7, 1963, at which time, unless otherwise ordered, let the sentence of death be executed.”

On May 29, Wallace granted Washington another reprieve until August 9. On July 19, 1963, the governor postponed the execution until November 29; on September 19, he delayed it until December 6. A reporter for the Birmingham News branded Wallace a “softie when it comes to staying the execution of Kilby Prison Death Row inmates.” Washington and seven other inmates were all scheduled to die on December 6. “If the governor does not again deal out mercy and all eight are executed,” the reporter added, “it will be an all-time record for the more than 30 years the state has been executing condemned men in the Kilby electric chair.” Joining Caliph for the December 6 date were Drewey Aaron, William F. Bowen, Roosevelt Howard, James Cobern, Johnnie Coleman, Robert Swain, and Leroy Taylor. “Governor Wallace has said little about how he feels,” the News reported, “but judging from the past, most guesses here are that more reprieves will be granted.”

The journalist was correct. On December 3, Wallace granted Washington another reprieve and pushed the date of execution back to February 28, 1964. At the time, one Alabama newspaper editor complained that although Wallace had a reputation as a “wicked despot and race-hater,” he was proving “to be the most soft-hearted of all Alabama governors” on the death penalty. The delays continued. On February 25, Wallace gave Washington until April 10; on April 6, he gave him until June 26; on June 16, he gave him until September 11.

While Caliph waited and prayed, the Civil Rights Act of 1964—outlawing public segregation—took effect on July 2. Five days later in Bessemer, a group of black teens decided to test the act’s public accommodation provision at McLellan’s store, located in the business district on Second Avenue and Nineteenth Street. Inspired by the civil rights campaign in Birmingham a year before, classmates Edward Harris, Albert Shade, Tommy White, Willie Duff, Herman Williams, Herbert Pigrom, and three others decided to eat at the store’s segregated lunch counter on Tuesday, July 7. A nervous waitress asked, “What do y’all want?” The teens ordered cherry Cokes and she responded, “You know y’all not supposed to be over here.” From the front window, the manager spotted a group of white men walking towards the store carrying child-size baseball bats. He tried to lock the doors before they entered, but they forced their way inside, ran to the lunch counter, and began beating the teens. Without training in nonviolent direct action, the boys fought back as they dashed for the exit. “It wasn’t like we were going to sit there and take a beating,” Pigrom recalled.

By the time they made it out the front door, the store was in shambles and blood stained the floor. Police Chief George Barron said none of the white assailants could be identified, and no charges were filed. “We were naïve enough to think the law was the law,” one of the teens later said, “and things were going to change.”

In the nearby Jefferson County Courthouse, a grand jury urged the governor to allow Caliph Washington’s sentence to be carried out and demanded that no clemency be considered “for such a cold-blooded murder and the taking of human life.” During Wallace’s first eighteen months in office, he gave Washington seven reprieves and scores of others to the rest of the death row inmates.

While no prisoner died in Big Yellow Mama during those months, this changed in the fall of 1964. James Cobern, a white thirty-eight-year-old itinerant farm worker from Chilton County, had been on death row since being convicted of the 1959 murder of his ex-girlfriend, Mamie Belle Walker. Walker’s mutilated body was found near the café she owned in December 1959, and Cobern was sentenced to death the following year. After granting eleven stays of execution, Wallace allowed the sentence to proceed upon the twelfth request. Hundreds of letters poured into the governor’s office asking that Cobern’s life be spared, but the governor held fast. The evening of September 3, Cobern ate his last meal: chicken, french fries, rolls, milk, coffee, and coconut cream pie. Cobern smiled and shook hands with guards, ministers, and onlookers as he went to the electric chair. His last words were “Everything is all right.” He died at 12:14 a.m. on September 4.

For Caliph Washington, Cobern’s death cast a foreboding shadow on his scheduled execution a week later. Would Wallace deny Washington’s request? Would he be the next person to die in the Alabama electric chair? On September 8 at the clemency hearing, Washington begged Wallace, “Please spare my life.” Wallace told Washington that he “agonized over such matters, but it is a decision the governor must make.”

Two days later, on Thursday, September 10, Caliph Washington had still received no word from the governor. He took up residence in the Bible Room and spent his time praying. Just hours before he was due to sit in the chair, Wallace issued another reprieve and reset the execution for September 25.

Time, which was once Caliph Washington’s only friend in prison, now became his most feared enemy. With each reprieve from Wallace, the next execution date was set closer. In the next six weeks, Caliph would have five more clemency hearings, and Wallace would test his solemn responsibility. On September 24, the governor issued another stay just a few hours before Washington’s scheduled death. The new date was set for October 9, but Wallace issued yet another late reprieve to spare his life. He delayed the October 30 execution on the evening of the 29th. The next date was set for November 20, but he stopped the proceedings on November 19. The state rescheduled the electrocution for December 4, 1964.

Wallace’s thirteen stays of execution prevented Caliph Washington from taking those final thirteen steps into the broad maple arms of Big Yellow Mama. The governor received several letters urging him to give Washington more time. “There seems to be a reasonable doubt of his guilt,” Birmingham resident Eileen Walbert wrote on December 1. “It would be a terrible thing if an innocent man were to die. I beg of you to spare his life. At this season of the year it would be a wonderful gift for us all.” On December 2, Wallace again heard Caliph’s plea for clemency. Following the hearing, he retired to his office to consider a fourteenth reprieve.

Early the next morning he issued an executive order. “After oral hearing and careful consideration of the facts,” he wrote, Caliph Washington should not receive executive clemency. “Therefore, let the sentence of the court be executed as provided by law.” The final decision came over seven years since the incident with Cowboy Clark, five years since the last conviction, and twenty-three months since the appeal was denied. It followed thirteen reprieves from George Wallace.