The most common, and the most repetitive, job we ever did as sheep and beef vets was pregnancy testing cows. Most progressive farmers, and even a few who might not be described that way, see the necessity to check the cows, mostly in the first trimester of pregnancy, to see if they’re in calf. There are several reasons for doing this.

First, an empty (or dry) cow is not going to produce anything to sell. She’s also eating a lot of grass, energy that a pregnant cow could be putting into her calf. Another reason is that the autumn and early winter is a time when there’s not a lot of cash coming in for most sheep and beef farmers, so the sale of any empty cows helps the bank balance. A final reason is that an abnormally high number of dry cows gives the farmer a heads-up that there’s a problem. Is there an infertile bull, or a mineral deficiency? Is the farmer not feeding the cows enough or, worst of all, is there an infectious disease such as vibriosis (a bacterial disease of the reproductive tract) in the cows?

So pregnancy testing is a crucial part of the rural vet’s life, and every autumn we’d begin to test, or PD (pregnancy diagnose), the herds in the district.

It’s a tight breeding year for the average cow. Her pregnancy takes 275 days, she then has at least six weeks of post-partum anoestrus before she starts cycling again, which only gives her about 50 days at most to get pregnant if she’s going to calve at the same time each year. She only cycles every 21 days, so she’s got to get pregnant in the first or second cycle. Late calvers lead to all sorts of practical difficulties, and an uneven line of calves to sell, if that’s the management on farm. It’s important for all cattle farmers, beef or dairy, to have a fertile herd which more or less sticks to a schedule, and whose cows calve within a relatively narrow timeframe.

If all this is a bit tedious to read, I apologise, but it’s a significant job and the practice of pregnancy testing led to a number of stories which we found pretty funny.

Marlborough is an extensive region, with long drives up and down dusty, blind-ended roads, and often long drives between properties, so we spent many hours on the road at PD time of year. I really enjoyed it. We were working with fine people who became our friends and the job itself was a good one, once you were fit for it. We did it all manually, and it was healthy hard work. These days ultrasound scanners have made the job much less physically demanding.

In my first year there was an element of anxiety. Like most new graduates, I hadn’t done enough PD to be really confident, and I sweated my way through the first few herds. If I made any serious mistakes, I now apologise to those farmers, but no one ever accused me of doing so.

Later, it became very routine, but I still enjoyed it, yarning to the farmer, who was probably catching the cow’s head in a crush and holding it while I shoved a lubricated gloved arm into the cow’s rectum, and with my fingers palpated the uterus underneath it, through the rectal wall. A pregnant uterus contains fluid, and after about eight weeks of the pregnancy you can ‘ballot’ the foetus, that is, feel it bouncing in the fluid with the tip of your fingers.

One of my favourite places to go for PDs was Bluff Station in the Clarence Valley. The front country is in the Kekerengu Valley, 45 minutes south of Blenheim on State Highway One, but the bulk of the property lies out of sight of the casual observer, in the mighty Clarence Valley.

The Clarence River begins in the Molesworth/St James headwaters, not far from where a number of the big rivers of the northern South Island originate. The Waiau, Wairau, Clarence, and even the Buller headwaters all come from an area the size of one large station.

The Clarence then runs south towards Hanmer, turns eastward then northeast and courses between the two great Kaikoura Ranges, Seaward and Inland, before cutting out to the east coast at Clarence Bridge.

Bluff Station occupies a very large area of the more northern part of the river, and lies against the eastern side of the Inland Kaikouras, with the great mountains of Alarm and Tapuae-o-nuku the dominant land forms. We would test the cows at three or four different yards, at various places throughout this long station, usually 200 to 400 at each place.

One day, sometime in the 1980s, I left home early to go and test all the cows at the Bluff. I’d be away for two days, as it was a good three hours’ driving from the homestead to the back yards at the Branch, the furthest outpost on the station.

I was, as always, excited to be going there. It’s a magnificent wild place, and Chid Murray, the owner, is a good friend. Sue, his wife, has been a lifelong friend of Ally’s too, so it was more than just a business trip. It was fun. Not many people get to see Bluff Station and I always found it a special place.

I was at the Glencoe homestead at Kekerengu by 8 a.m. and, I can’t be sure, but I probably left my vehicle there and travelled with Chid in his 4WD Toyota. Or I might have taken mine. Over the hill we went to the major outpost of Coverham, where the married couple lived, about 45 minutes from the front. The road was windy and the going slow; in this modern world it took a special type of couple to live there. They did have power, and could just get TV, but otherwise they were fairly isolated.

At Coverham we picked up a couple of men, and in two or three trucks headed south, up the valley. Other men were already at the back of the station, mustering the cows. The rough road runs along the back of the Chalk Range, a long and steep limestone ridge which runs parallel as a sort of foothill range to the main Inland Kaikoura Range. A number of sizeable streams draining the range cut through the limestone, and each of these has to be forded, which isn’t always possible in wet weather.

There is an outstanding geological feature of world significance here, one I knew nothing of in those days, and many times I blithely drove or was driven past it. At the Mead Stream a great twisted and curved limestone face, 200 metres high, has been exposed by centuries of river action. In the middle of this strata, a thick dark line, curved as the earth has twisted it, divides the face. The bottom edge of this dark line, where it transforms back to white limestone below is of great significance. It marks the K–T boundary, the exact year in which the Cretaceous period ended and the Tertiary began. This is one of many sites in the world where this phenomenon, identified by geologists in the late 1980s, can be seen.

At that point in time, 66 million years ago, a meteorite smashed into Mexico, causing massive and ongoing atmospheric dust, climate change and chemical change to the whole world. It was the event which led to the rapid demise of the dinosaurs and a chain of biological evolution which eventually saw the human race emerge as the dominant species on earth. The evidence is right here in Marlborough and of immense significance to our understanding of the history of our planet. But I knew nothing of this, as we crossed first the Swale, then the Mead and the Limburn, and finally the Dee, and climbed out to the Branch hut and yards.

It was a beautiful day and I can still see that magnificent landscape, the two great ranges, the men bringing a couple of hundred cows in from the holding paddock.

We had a quick bite of lunch, then I stripped, donned my overalls and apron/leggings, taped myself into two pairs of plastic gloves, and we were away. Chid was on the head bail catching the cows to hold them still, and I moved in and out of the vet gate, testing each one in turn, lubricating my arm every four or five cows to make the job easier.

Each time I pushed my arm in, I could turn my head just a little to the left and see the mighty peak of ‘Tappy’ high above. Chid and I yarned and the job was going well. Most of the cows were pregnant, but a number of young cows were often dry on the Bluff in those days. Chid was developing the country from rough scrub, and it was hard to find enough feed to give the first calvers the preferential nutrition they needed. The result was that a higher number of those cows didn’t cycle in time to get pregnant second time around. It took a few years to beat the problem, but as the development kicked in, things got a lot better. At the time it worried Chid quite a lot, and I was very conscious of that. Pete A and I worked with him for several years to solve the problems, and his farm consultants were important to him too.

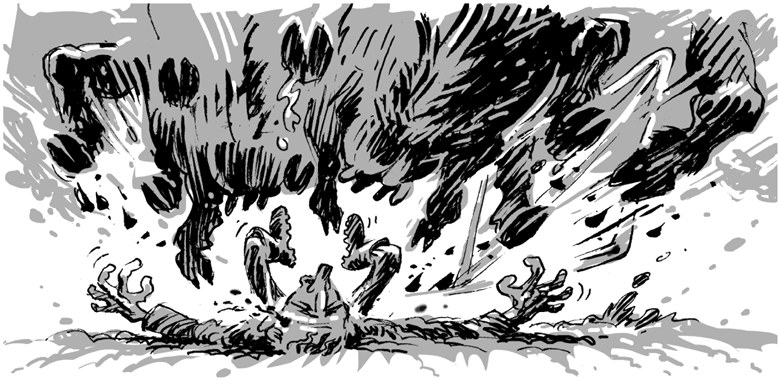

After about an hour, when I’d tested around 100 cows, the pen behind was empty. The men had gone off on horseback to get another mob up, so Chid and I went back to bring another yard full of cows up towards the race. I wasn’t concentrating enough, and as we shooed 30 or 40 cows into the yard, I closed the steel gate a bit fast. The gate touched the hock of a cow and the laws of Newtonian physics were immediately realised as she kicked. Her hoof caught the gate at maximum velocity, the gate swung back violently, and hit me hard on the temple. I went down like a sprayed fly, and I can just recall lying in the mud, with cows running back over me, and Chid standing over me keeping me from further harm.

I think I must have been unconscious for a second or two, and I was a pretty sick boy as I clung to the rails of the yard, bleeding like a stuck pig from the wound over my right eye. I felt terrible, and Chid obviously didn’t like the look of me. He was quickly on the two-way VHF radio in his truck. ‘Bluff to Muzzle …’ and in a few seconds Tina Nimmo at the Muzzle, a few miles upstream, was there.

‘Pete’s had a whack. He needs stitching. Can Colin take him out to Kaikoura?’

Colin could, and in half an hour the Cessna 180 was trundling up the airstrip half a kilometre away. I was bundled in beside Colin and we roared off across the valley, up, up and up against the Seaward Kaikouras, then over and down to Kaikoura’s airstrip. At any other time it would have been exhilarating, but I wasn’t in great shape and I didn’t really appreciate it that day.

Colin and Tina Nimmo lived in one of the most inaccessible stations in the South Island, Muzzle Station. The only road access is either over the Inland Kaikouras then across the Clarence River in a difficult ford, or through Bluff Station on the track I’d come in on. When the rivers are up, there’s no road access, but Colin has a helicopter as well as his fixed wing aircraft, and they’re a hardy, self-reliant, cheerful and lovely couple. They have brought up their two daughters in fine fashion over the last 35 years, while farming a difficult place extremely well. It’s now farmed by their daughter ‘O’ and her husband Guy Redfern, but this was well before their time.

At the Kaikoura airstrip one of Colin’s mates picked me up and took me to the little hospital. The legendary Geoff Gordon, the town’s long-standing doctor, was there. I was in my overalls, covered in cow manure, bleeding and dazed.

‘That needs a few stitches, Pete,’ he said, and in a few minutes had stitched me up.

‘How long since you had a tetanus shot?’ was the next question.

‘I don’t know, Geoff, a few years I think,’ I mumbled.

‘Well, you’d better have one,’ he said, and without further ado stuck the needle of the syringe with the tetanus antitoxin through a layer of solid cowshit on my upper arm and pushed the plunger.

I was highly amused, if a little shocked. I thought maybe a bit of a wipe with meths on cotton wool might have been the thing. You know, for hygiene purposes.

Geoff was happily unconcerned. ‘You’ll be right. See you next time.’ He grinned, and that was that.

We went back to the aerodrome, and half an hour later we were back at the Branch. Chid was concerned about the hold-up, but he could see I wasn’t feeling great. My head, swathed in a wrap-around bandage, was splitting, and I wanted to be sick, and was.

So the job was postponed for the day, and instead of doing 300 cows at the Branch, and another 200 at the Mead yards, an hour down the track, we’d only done 100 for the day. The men did a few jobs, I went to bed, and at mealtime there was a bit of tension in the camp.

The next day was the hardest I ever did as a vet. I had a vile and constant headache and felt ghastly. But there was a job to do. With my heavily bandaged scone, I worked my way through the 200 cows at the Branch, then moved to the Mead, and did another 200. By then it was early afternoon. I had to tell Chid I needed food, so we stopped for a bit, but there were still another 300 at Coverham, another hour away.

I can just recall a pretty horrible three or four hours there, and by the time we were finished the sun was down. I drove home, sick as a dog, and spent the next day in bed. I’m sure I was concussed — I know Ally was a bit concerned.

But that experience didn’t affect my great love of Bluff Station. I went there many times, both working and on hunting, social or climbing visits. On one trip five of us climbed Tappy, 2883 metres (9460 feet), from the Branch, camping on the tops the first night. Bob Rutherford was 75 at the time, and though he told Bill Lee, his son-in-law, to ‘just cover me up with stones here’ if he didn’t make it, he got to the top and down safely.

It’s a wonderful property, magnificent country, and I’ve always loved going there.

But I never forgot the Kaikoura tetanus shot — straight through the cowshit.