Christmastime 2018, I sit down to lunch with some suspicious characters: my family.

It’s unusual for us to get together like this. After years of avoiding being in the same room, my parents have recently softened toward each other. Laughter rises toward the ceiling as we pass a platter of deli sandwiches around the table.

My dad is semiretired from nursing, the years of physical labor having taken a toll on his hips and back. After coming into a modest inheritance, he and my grandmother Jan pooled resources to buy a quirky mid-century modern house on a little hill overlooking glassy Clear Lake about three hours north of San Francisco—where we’ve gathered for lunch today. Original artwork enlivens every wall: my dad’s vivid visionary paintings juxtaposed with the subtle elegance of my grandmother’s modernist work. Recent wildfires scorched the surrounding hills, but the home and garden have come through unscathed.

Doug (as my dad now calls himself again) is sitting beside his live-in boyfriend, Rick. At sixty-five, my dad is finally out of the closet as bisexual and in love with a proud gay man. It came as a surprise to ninety-four-year-old Jan, but she’s gotten used to it. Rick is charming and handsome, and takes zero shit from my dad. They kiss in public. This change didn’t come to my dad easily; he went through years of therapy, self-help workshops, and earnest introspection. At long last, he seems to have settled into his own skin, and that makes him a pleasure to be around. Rick, Doug, and Jan make an unusual threesome. They bicker, especially over control of the garden, but they also take care of one another and share the labor of running the household.

Today, my godmother Barb—the woman who perfected the Sticky Fingers recipe and introduced my parents—is also here. She has the same apple-cheeked smile and wheat blonde hair as in my earliest memories, and she still smells of cigarettes and the jasmine-scented French perfume she’s been wearing since 1973. Now retired from costuming, Barb lives on the other side of Clear Lake with her husband. She still loves to bake.

Sitting beside me is my mom, visiting for the holidays from Desert Hot Springs. A little shorter and rounder than in the old days but no less striking. She dyes her hair burgundy and wears it short. Her blue-green-amber eyes can still arrest you from across the room.

Of the three former outlaws at this table, she’s the only one still hustling—not pot these days but art. While Barb and Doug both worked straight jobs for years after Sticky Fingers—accumulating Social Security and retirement benefits—my mom still cobbles together a living from her artwork. She maintains a grueling teaching schedule and spends every morning off painting. “No rest for the wicked,” she says. The pace is exhausting, but she’s passionate about the work she does.

At seventy-one, she’s been talking about moving to New Orleans, where she doesn’t know anyone. “I might have one more reinvention in me,” she says, eyes wide with possibility.

To look at this group of gentle people, their faces lined by loss and softened by experience, you’d never take them for the masterminds behind a complex outlaw operation. I suppose this is one of the advantages of aging: presumed innocence.

Left to right: Alia, Barb, Meridy, Doug.

And yet, when Barb arrived today, the first thing she did was hand out cookies wrapped in red cellophane and Christmas ribbon.

“Be forewarned,” she said. “They pack a wallop.”

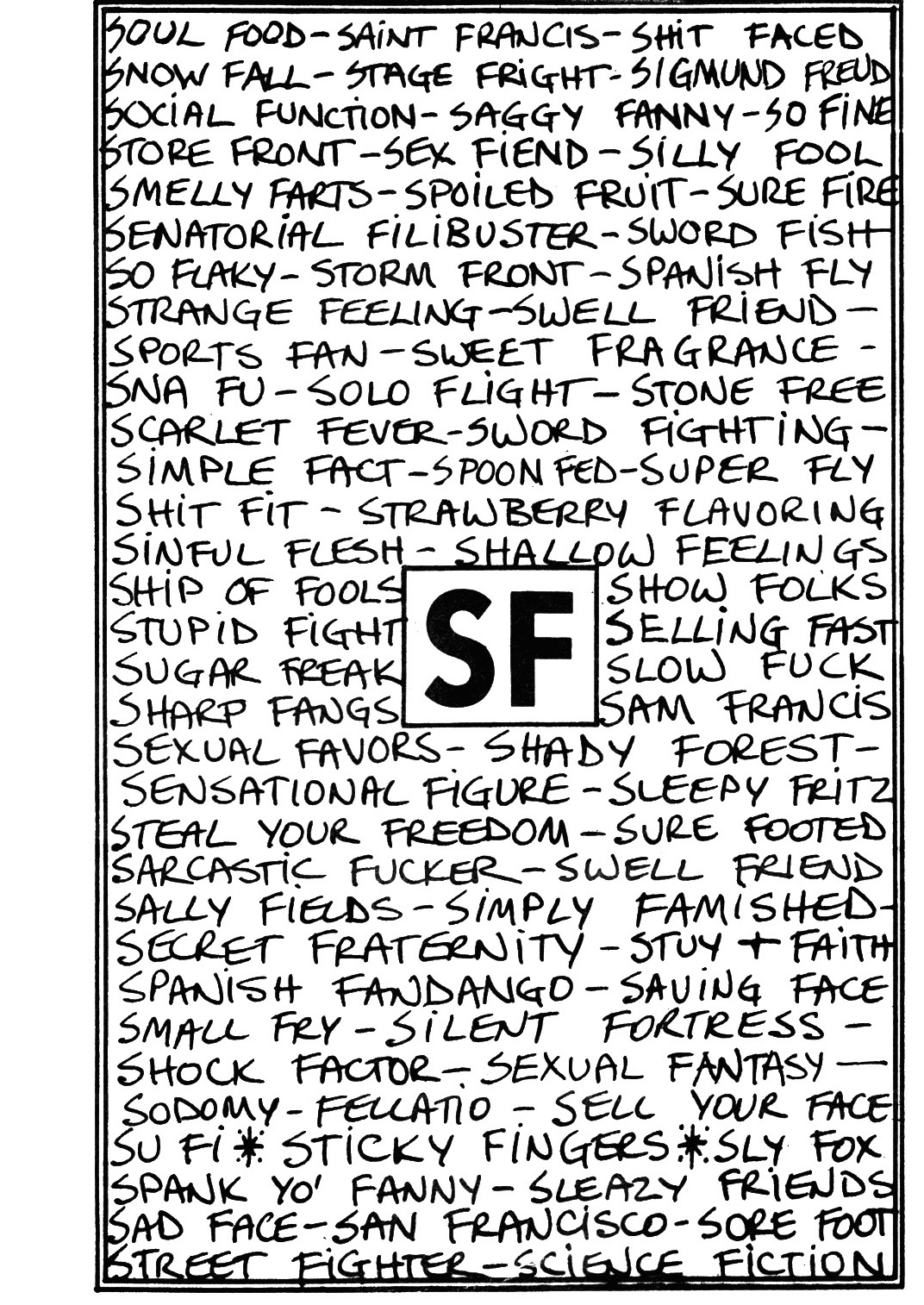

Sticky Fingers Brownies began as a lark and grew through friendship, feminist badassery, and hippie magic. Back when it was unequivocally illegal, before tragedy brought pathos and respectability to dealing. Barb innovated a recipe that people still crave today. Doug conceived of the packaging as a means of transmitting messages to the community and spreading awareness through art. Cheryl brought glamour to the operation. Carmen and the Wrapettes mixed and warmed and packaged it with love. The business model Mer had envisioned at the Ransohoff’s Christmas fair in 1976 metamorphosed naturally when the crisis hit. Working solo through the 1980s and 1990s, she bent through the arc of necessity to deliver relief to those in need.

“It’s kind of fascinating when you think about it,” Cleve Jones said one day. “But your mom and Brownie Mary and Dennis Peron really are the reason why marijuana is legal now, because no one had thought of compassionate use.”

Cleve was right about that, though my mom’s place in cannabis history is little known. She wasn’t a hero of the legalization movement—not like Mary Rathbun or Dennis Peron, both of whom did jail time, worked the media and the court system, and ultimately changed laws. But by building that first huge illegal edibles business and sustaining it through the crisis, my mom reshaped the landscape.

For nearly a quarter of a century, she flew below the radar, working in the shadows of those who went public in the industry she helped create. From party drug to panacea. She and her collaborators blazed trails that are still being followed today.

In intervening decades, the rest of the Sticky Fingers family has scattered. Shari Mueller, the Rainbow Lady who started it all, now lives with family in Virginia. Donald Palmer, Mer’s first partner in crime, moved back to Wisconsin to teach piano; he died in 2016. Cheryl Beno lives on a quiet mountaintop near Willits. Mumser plays harmonica and sings in a rock band in Garberville. Carmen Vigil has put down roots in Colorado, and his son Marcus started his own family in Oregon. Eugene “Jeep” Phillips still does his carpentry and art projects in San Francisco. Stannous Flouride is here, too; he guides tours of Haight-Ashbury. Dan Clowry retired from nursing in 2015 and has been traveling the world—Hong Kong, Japan, France. After more than thirty years with the SFPD, Jerry D’Elia retired as a sergeant in 1999, opting for a mellower lifestyle north of the City. Cleve Jones has authored two memoirs, one of which became the subject of an ABC miniseries in 2017. He remains a committed activist and still leads protests in San Francisco. Mary Jane Rathbun passed away in 1999.

The Prince of Pot, Dennis Peron, died in spring 2018, about a year into California’s implementation of fully decriminalized recreational marijuana. Dennis had actually campaigned against Prop. 64, seeing it as a poorly crafted piece of legislation that would harm small farmers. He was not wrong. While legislation included a one-acre limit for the first five years, ostensibly to protect the little guy, a loophole allowed big investors to buy unlimited numbers of these small permits. “Local businesses and nonprofits are all suffering,” Mumser says. “People used to make money to give to the fire department or the school.” Drive through Willits or Garberville today, and you see businesses shuttered, plywood nailed across windows. Still, I like to imagine that Dennis—who’d fought cannabis prohibition in California for almost five decades—derived at least a little satisfaction from seeing that hurdle cleared in his lifetime.

A new generation of marijuana activists and entrepreneurs is rising to prominence. Mostly millennial and younger, they are sharp, ambitious, and innovative. Some current activism revolves around ensuring that communities of color—hardest hit by the drug war—won’t be shut out of what many are calling the “green rush.” Financial and bureaucratic hurdles can make cannabusiness licenses available only to the wealthy and connected. Meanwhile, drug busts continue; in late 2018, the FBI reported an average of one marijuana bust every forty-eight seconds. Black Americans are almost six times more likely to be incarcerated for drug-related offenses than their white counterparts despite similar usage rates. And in many locales, prior drug convictions bar people from obtaining cannabusiness licenses. A few cities, including San Francisco, have announced programs to expunge lower-level marijuana convictions from criminal records, but the work in this area is barely beginning.

Still, the rate of change in recent years has been staggering; the laws may shift again by the time this book is released. New products and business models abound, which would have been unthinkable in the 1970s before illegal enterprises like Sticky Fingers Brownies laid the groundwork. My folks took risks that today’s cannabusiness innovators don’t have to worry about. It’s a new era in the world of weed.

In truth, we owe our lavender-scented THC bath salts to activists who fought for access during the AIDS crisis. Many of the people who carried the movement on their backs didn’t survive to take credit. Younger generations now enjoy the benefits of decriminalized marijuana heedless of the mortal struggle that brought it to them. I’m glad things have changed, but the collective amnesia disturbs me. According to the CDC, nearly 380,000 Americans had died before Dennis pushed Proposition 215 through—beginning the long process of revamping marijuana’s image. That legislation would not have passed if the horrors of the plague hadn’t become impossible for California voters to ignore. Cannabusiness crossed a bridge of human bones.

Later, after Barb has gone home, the rest of us retire to the living room. We’re all drained from a long afternoon of catching up. Here, a strange thing happens: We watch reruns of The Golden Girls.

I look around—my grandmother in a rocking chair, my mom kicked back on a La-Z-Boy, my dad and Rick snuggling on the couch. On TV, Betty White is trying to teach a chicken to play the piano. Everyone laughs.

I don’t know what it means, this moment, but it’s warm and surreal and it feels like family.

Back in her daily life in Desert Hot Springs, my mom doesn’t talk about her role in cannabis history. She never sought credit or notoriety and has been content to keep the stories to herself—frankly relieved to have gotten away with it. She’s put those years behind her.

She paints religiously, amassing a vast body of work, which is often shown in galleries and museums in Palm Springs. She teaches art to a range of students, from kids to older retirees. Her favorites are the ones she calls her “naughty kids”—teenagers who’ve gotten into trouble with the authorities and been classified as “at risk.” For my mom, those who push boundaries will always be her kin.

Of course, she doesn’t reveal her former life to her students. But some of them seem to sense the history she’s hiding. Every so often, they’ll try to coax it out. “Hey, Ms. V, were you a hippie in the old days?” one kid prods. “Did you, like, smoke pot?”

“Ask me no questions and I’ll tell you no lies,” she says, turning back to the easel where she’s demonstrating the day’s assignment. “Let’s just say I’ve had a colorful life.”