Meridy liked this new side of herself: the outlaw entrepreneur. Stepping out to work the wharf each weekend, looking sharp, she felt her energy crackling dangerously—a stripped wire. Her circle of acquaintances grew exponentially, and her reputation began to precede her. “Oh, you’re the Brownie Lady!” Among the wharf characters were several fine men to flirt with. She had fair-weather boyfriends here and there, hey-baby-free-love romps, and the occasional awkward orgy—but nothing she could hold, nothing to return to. Most nights, she spent sprawled between cold sheets.

Granted, she was choosy. She wanted a knock-down, drag-out, transcendental romance. She didn’t go for the bucket jaw, toothpaste teeth, harmonica mustache look that was mainstream. Forget Burt Reynolds; bring on David Bowie! Creative, slightly broken, effeminate types gave her butterflies. She considered herself an artistic genius and was, at the very least, an artist of significant promise, therefore she wanted a lover of the same ilk. A Diego to her Frida, a Rodin to her Claudel. A man who dealt from a full deck of cards.

Preferably tarot cards.

But whenever Mer felt a genuine zap, the guy backed off. She had a knack for both dazzling and scaring the shit out of the opposite sex. As the Butterfly Man, one of her wharf customers, would recall decades later, “She was a striking lady. Kind of terrifying, to tell you the truth.” So despite possessing intelligence, good looks, and cojones—or maybe because of these traits—Mer drummed her fingers in fern bars on Clement Street and cafés in North Beach, waiting.

Barb kept saying they needed to find her a magician.

He’s here somewhere, Mer thought. Somewhere in this seven-mile town.

He was about three miles away.

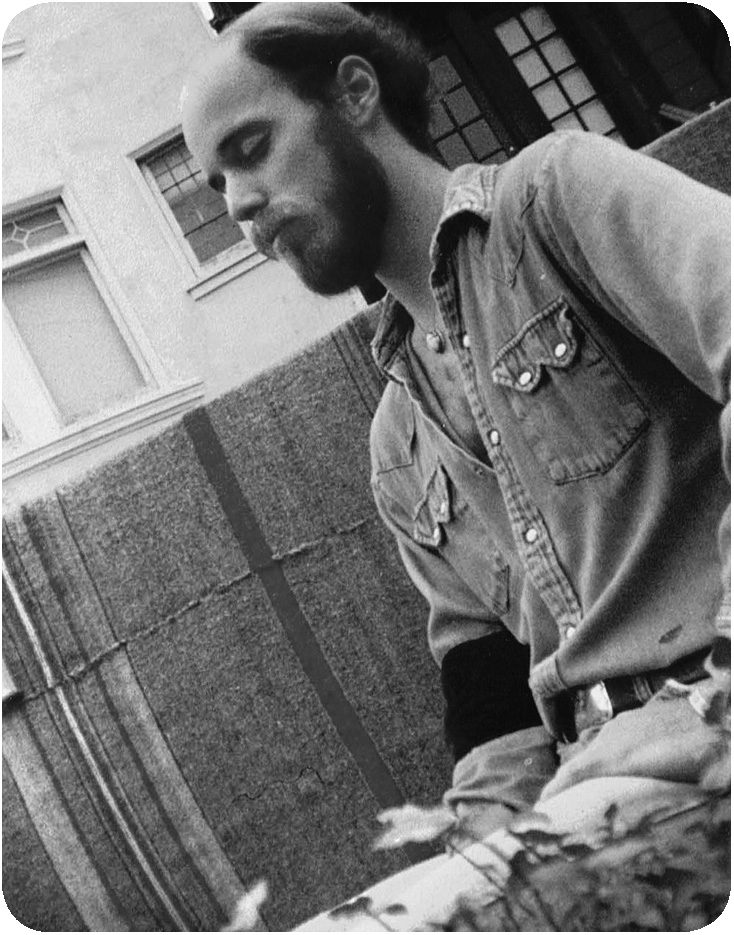

My future father walked the Mission toward what he didn’t know. He liked to be on the street, checking people out, getting checked out. He stood an even six feet, with good posture beaten into him at boarding school, and moved with an easy long-legged swing. Music in the wooden heels of his cowboy boots striking the sidewalk, rhythm in his hips. On a clear day, he was the kind of guy who would try to stare directly at the sun and meditate—once burning his corneas so badly that he had to wear gauze patches.

He walked, destination wherever, soaking in the scene. Passing the Sixteenth Street BART station, he checked out the Chicanos in high-waisted slacks and bandannas. Round brown-skinned women selling tamales. The crowd surged and ebbed. Occasionally, he’d see another freak coming the other way. They’d lock eyes and nod, a current passing between them. He could get overloaded with energy, like a circuit breaker receiving too much juice. He’d been trained to read auras, and sometimes he couldn’t turn off the colors enveloping strangers. He liked the smell of grilling meat, the sound of ranchera music a little circusy to his ears. The funk of junkies, the occasional rainbow of a kindred spirit. He walked, feeling alive inside his skin. We are all one light, he thought. All the world’s children . . .

It was Barb who found him.

John Battle, the Viking carpenter she was dating, had recently moved into an enormous warehouse on Twentieth and Alabama streets in the Mission. “I’m living with all these kooky psychic hippies,” he told her. “You won’t believe my housemates.”

Barb liked kooky psychic hippies. She visited John at his new space, and that’s where she met Doug Volz.

Doug told her that he’d graduated from the Berkeley Psychic Institute the prior autumn, earning the grandiose title of ordained reverend of the Church of Divine Man. Barb had never heard of it. Doug explained that they trained students in clairvoyance, aura readings, chakra readings, telepathy, and telekinesis. When he mentioned that he’d painted a mural of all the graduates who’d preceded him in exchange for his tuition, Barb’s ears perked.

“Oh, you’re an artist?” she said.

“Come right this way.”

He directed her to sit in a straight-backed wooden chair facing an enormous triptych of canvases about seven feet tall and three feet wide. The central panel featured a life-size woman with long blonde hair sitting on a wooden chair and staring frankly out at the viewer, palms resting on her knees, as if about to give a psychic reading.

“I call this piece My Old Lady Is a Dancer,” Doug said. “It might not look like she’s dancing, but sit with her for a little while. See what happens.”

Barb could feel Doug eyeing her for a response as she tried to relax and focus on the painting. A green field stretched toward barren trees behind the seated figure and filled the other two panels. Puffy clouds drifted across an intensely blue sky. Doug’s style was photo-realistic; the detail was so fine that she thought he must have painted with the tiniest brush imaginable. But there was something otherworldly about the image, too. She looked at the woman’s calm brown eyes, and the painting began to move: the grass swayed, the blonde hair twisted in the wind.

Oh, my God, Barb thought. Doug and Meridy are going to be together.

By early November, the bakery was running low on magic ingredient. Mer sent a letter to Betsy and Mumser saying that she was coming back up for another visit. She didn’t hear back right away, so she and Barb decided to drive up on a Sunday and take their chances. The season had been dry, the drought deepening, but a soft, welcome rain fell that afternoon.

On the way up, Barb told Mer about the handsome psychic she’d met. “I got his number for you.”

“I can’t call this guy out of the blue,” Mer said. “I’ve never met him.”

“Oh, come on,” Barb said. “What do you have to lose?” She cajoled, but Mer dug her heels in and changed subjects.

They drove all the way to Garberville only to find out that Betsy and Mumser had harvested late and were still drying their plants; they didn’t have any shake ready.

“It’ll be all right,” Mumser said. “Plenty of us up here.” She put a call out on her CB—which people in the community used to track storms and wildfires and notify one another when law enforcement was prowling. “This is Merry Widow,” she said, winking at Barb and Mer. “Anybody got eggs for sale out there? Got friends up here looking for eggs. Over.”

Eggs. A codeword, apparently.

The radio was quiet. Then a voice broke through. “Affirmative, Merry Widow, I got some eggs.”

Mumser drew a complicated map, which Mer and Barb followed down unmarked dirt roads into the deep woods. The rain swelled from a sloppy drizzle into a downpour, and liquified clay streamed from the roads, exposing hunks of rock and giant potholes. They ground up a precipitous hill, then sharply down. At the nadir, a roiling brown creek cut across the road. Someone had laid two planks across the surging water.

Barb hit the brakes. “I don’t know about this. If we go in that creek, we’re screwed.” Barb’s 1966 Datsun pickup didn’t have four-wheel drive. If they got stuck, they’d be marooned in the deep boonies. Miles from any phone booth, they’d have no way to call for a tow truck. It was a narrow road. On one side, snaky black roots laced a tall clay bank. On the other was a sheer drop into the woods, an ocean of pines and redwoods rolling into the gray distance.

There was no room to turn around, no chance of backing up the steep hill.

Nowhere to go but forward.

Barb exhaled slowly. “Promise me you’ll call this guy and I promise you we’ll make it.”

Mer gave her a sidelong look. “Fine. It’s a deal.”

Barb patted the dash, and Mer white-knuckled the door handle, as they eased toward the creek. Milkshake-brown water licked the boards. Barb kept her foot steady on the gas and gripped the steering wheel at ten and two. The boards shuddered under the truck’s weight but did not give.

“Yahoo!” Barb screamed on the way up the next hill. “I feel like we’re in a movie!”

Mer and Barb bought everything the guy had, three fat black garbage bags full of shake—thirty pounds total—crammed it into the cooler in the back of the truck, and covered it with a tarp.

The drive home was nervous, slow, careful.

That much weed, they knew, could send them to prison for years.

The first phone call between Mer and Doug was awkward, but Barb had prepared them both.

“I hear you’re good with the tarot,” Doug said. “Well, you know, I’m trained to read auras. Since we’re both into psychic work, why don’t we exchange readings? Let’s skip all the bullshit and pretension, and find out who we really are.” He laughed in a way that made it sound like an adventure.

Mer always liked to put her skills forward first, and she was confidant with the tarot. No matter what else happened, she figured she could give a decent reading. They agreed that Doug would come to her house first. Then, the following day, he’d read her aura at his warehouse. Tit for tat.

No coffee, no concert in the park, no wine to break the ice. Just a hard-core display of psychic chops: the hippie blind date par excellence.

Four decades later, two loose pages of my dad’s 1976 day planner surface in a box of old letters, offering a snapshot of his life. On November 8, there’s a dental appointment and the name Barbara Hartman circled, the day they first met. Later that week, my dad has scheduled three psychic readings, including one with someone named Estania and the parenthetical note SPIRITUAL-SEXUAL UNION.

I don’t know what that entails, and maybe that’s for the best. But it’s clear that my dad was making a go at becoming a professional. It might seem outlandish in any other time or place, but psychic work was serious business in the Bay Area in 1976. Multiple cities were currently embroiled in debates over the legalities of psychic services. The ACLU was suing the city of San Francisco over the right of palmists and other occult practitioners to advertise their services. And the California state senate was holding hearings on a bill to set up a statewide licensing system for astrologers.

On Sunday, November 14, Doug planned to fast, take mushrooms, and see a double feature of The Exorcist and The Other. Then, on Tuesday, November 16, there’s Meridy Domnitz’s name along with her address and phone number and the note 8:00 P.M. READING WITH.

“I have this clear image of the first moment I saw your mother,” my dad says, looking back. “Her apartment was up these long narrow Victorian stairs, and she was standing at the top with the light from the door shining behind her. I had to climb all the way up there to reach her. She didn’t budge, like, to meet me halfway or anything. It seemed to take a really long time. She was like no one I’d ever met before, that’s for sure.”

Meridy eyeballed her date as he climbed the stairs, thinking that Barb certainly had fixed her up with a good-looking guy. Doug had a full reddish beard; a strong, straight nose; high cheekbones; freckles; and light-blue eyes. He was tall, lean, and loose-limbed. He wore shitkickers and a leather cowboy hat—which made Mer smile. (She and Barb were both reading Even Cowgirls Get the Blues by Tom Robbins that fall.) Doug removed his hat at the top of the stairs, revealing a shiny bald crown like that of a much older man, though his skin was smooth and youthful.

She led him into her bedroom, which Mer had obsessively cleaned and arranged to perfect the gypsy boudoir vibe, replete with incense and flickering candles. She’d dressed simply in jeans and a slimming black turtleneck with an oversize ankh necklace. Her eyes were elaborately kohled and shadowed.

Mer chattered to fill the silence while showing Doug her latest artwork, mostly watercolors. The conversation began haltingly, but art loosened both of their tongues. They fell into a natural one-upmanship, each waxing about their own creative obsessions.

For the reading, they sat facing each other on Meridy’s queen-size bed. She felt a little intimidated—Doug was so cute and seemed to fit her parameters—so she took deep breaths to clear her mind. Once she hit her stride in the reading, she relaxed and let the cards guide her.

I wish I knew what my mom saw in the cards that night, but all she remembers is congratulating herself on giving him a good reading. My dad isn’t any more helpful, his memory coming up blank.

Did she draw the Lovers and get distracted by a fluttering in her stomach, wondering if the lover in question might be her?

Did she see opportunity on his horizon, maybe the Ten of Pentacles, a hint that he was about to go from chronically broke to joining an increasingly lucrative illegal enterprise that would sustain him for years?

Did she glean from the Empress card that he would soon create a child?

It’s also possible that she saw none of this, her reading totally off the mark, blinded by attraction.

Doug had an aloof air, traces of a British accent, and a goofy sense of humor that helped offset his arrogance. The reading opened lines of communication between them, and Meridy was struck by a sense of being on the same level, playing by similar rules.

“I have a little side gig,” she said, with a half smile she hoped was sexy. “I sell magic brownies on the wharf.”

“Well! I might have to try one.”

Perfect response. They shared a small dose, and Mer made herself more comfortable, propped on pillows. When she asked Doug about his family, his answer took her by surprise. His grandmother, Paula, who at that time was seventy-four years old, was married to a ghost.

He explained: Lieutenant Commander Edward P. Clayton had been a decorated frogman in World War II and Korea. He and Paula had had a tumultuous on-again, off-again affair for years, but circumstances kept them apart. Ed died of lung cancer in 1969. One year later, his ghost showed up in Paula’s bed and made love to her. She could neither hear nor see him, but she felt his touch. When the ghost proposed marriage through a Ouija board, Paula accepted and assumed his last name.

“She talks to him all day long,” Doug said. “In some ways, they’re like any married couple except that you can’t hear his side of the conversation.”

“Like The Ghost and Mrs. Muir,” Mer said.

“Every afternoon she has what she calls her ‘quiet time’ with Ed when she disappears into her back bedroom and he takes her all around her universe.”

“And is she otherwise . . . ?”

“Sharp as a tack. Totally conscious and present to this day. She just has an invisible husband.” He grinned at Mer’s astonished expression. “Gramsy’s not ashamed either, let me tell you. She is absolutely in love with her own story and trusts herself with complete conviction. Growing up, we were kind of like The Addams Family, you know? Anything was possible.”

An extraordinary response to an ordinary question. An answer a magician would give.

Doug drove away at midnight in a white VW notchback. From her window, Mer watched the taillights shrink, then flare, before vanishing around a corner. They had agreed that she would visit him at his warehouse the next day for her Berkeley Psychic Institute–style aura reading. She lay awake for hours after he was gone, replaying the evening.

Meridy’s footsteps boomed through the barnlike warehouse at 3117 Twentieth Street. Its floors were of rough, unvarnished wood and its ceiling soared high overhead. Skylights flooded the space with natural light. Freestanding walls, half-built rooms, and makeshift partitions, art everywhere. Doug showed her his visionary artwork—the large triptych Barb had described and a series of mandalas. His use of vivid color turned her on more than anything else.

In an open central space, Doug set up two chairs facing each other and directed her to sit, legs uncrossed, hands on knees. He closed his pale-blue eyes. “I want you to ground yourself,” he said. “Envision a blue cord running the length of your spine down through the floor and the building’s foundation into the earth itself. Plug yourself into the source.” He took long breaths through his nose, his features slackening.

Doug in trance.

Moments passed. A truck backfired outside. Then Doug extended the fingers of one hand toward Meridy’s lap. “This is the root chakra that connects you to Mother Earth. If anyone has hooked a cord into your root chakra, we’re going to detach it right now and send them on their way.” He flicked his wrist to the right, and Mer felt a lightness through her lower torso and groin. He moved up through the seven chakras, cleaning each one in turn. As he went, he mentioned images and feelings he found there. At one point, he smiled slightly. “I’m getting a clear picture of Shirley Temple,” he said. “A pudgy little girl in tap shoes trying to win the world over with a giggle.”

Mer had indeed looked like a brunette version of Shirley Temple as a kid. She’d taken tap lessons throughout her childhood, and she still saw herself that way—as a beaming, curly-haired stage hog dancing up a storm to make the City smile. He couldn’t have known her that well, and yet he did.

Doug had seen through the adult mask to the child she still was inside. The reading left Mer’s brain buzzing, a vibration around her third eye so intense it was slightly painful. Like coming down from an acid trip. She felt spacey and exhausted, but wide open.

She expected Doug to ask her on a real date. Now that they’d plumbed the depths, they could take a step back and have a little fun along with the intensity. She was ready to enjoy this guy.

But if Doug’s finest characteristics were on display in those first interactions, his worst were not far behind. Apropos of nothing, he said, “You know, Meridy, I was going to ask you on a date. But I’m going to have to reconsider. You’re holding on to too much, and it shows. You need to lose the weight.”

“You know your father,” my mom says, decades later. “Mr. Tactful.”

It’s true: my dad is infamous among our family and friends for making biting, off-the-cuff observations.

“How did you respond?” I ask.

“I was stunned. Hurt. After someone reads your aura, you’re very vulnerable. I left quickly.”

Doug doesn’t remember making this comment at all. Nor does he remember not making it. This isn’t unusual for him. My dad’s memory has gaps, some quite large. My family’s version of he said, she said arguments would be she said; he doesn’t remember.

My mom’s version prevails, though it bears mentioning that it’s not the only possibility.

At five feet five and around 150 pounds, Mer was a little plump, as she’d been since childhood. She dieted, did cleanses, took dance classes, overate, dieted again. Even her skinniest wasn’t skinny. She’d never have a Julie Christie figure. If that’s what Doug wants, she thought, we have no business dating. Another rejection for the compost heap. But this one stung more than usual because everything else had felt so right.

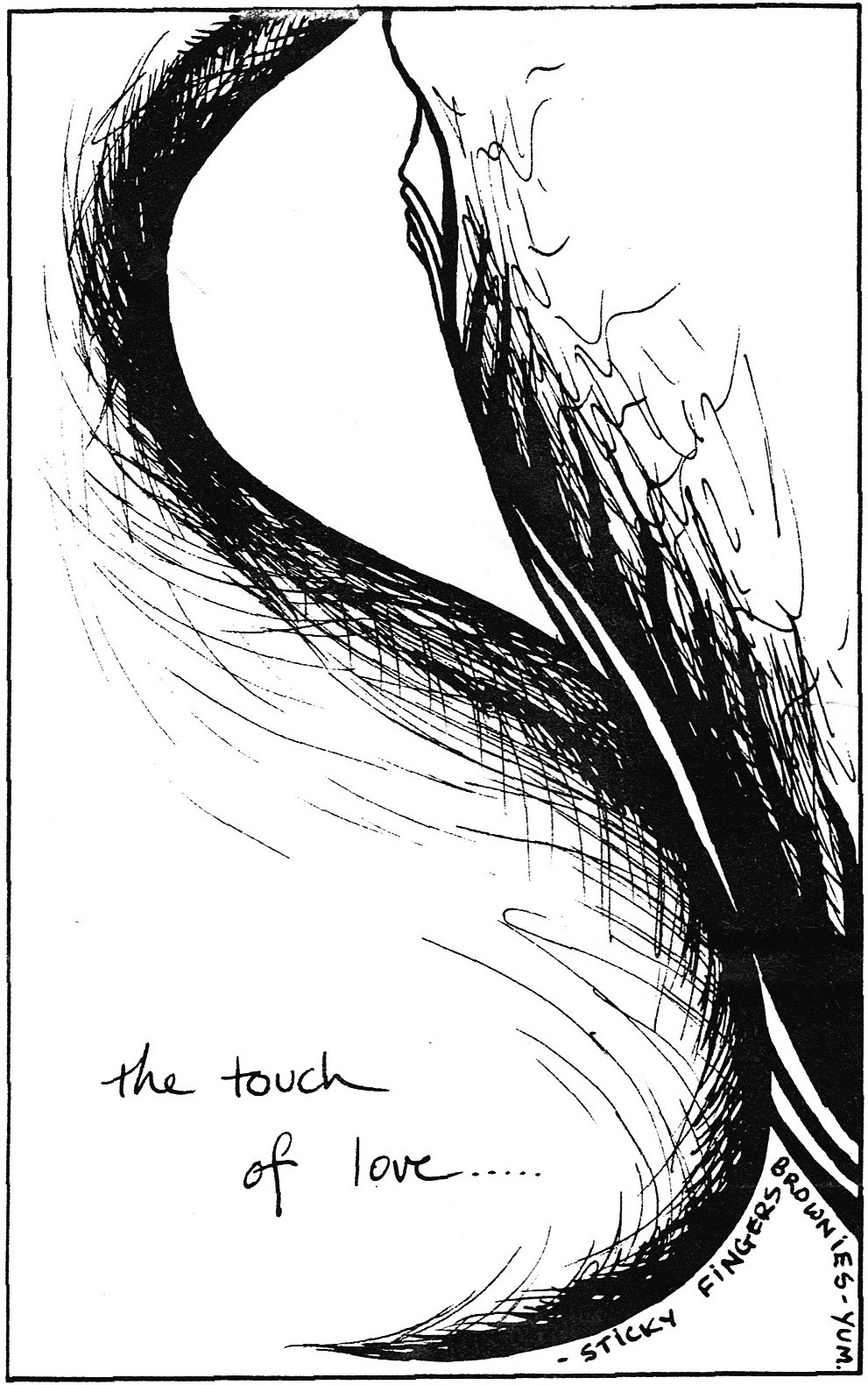

No time to mope. With Thanksgiving coming up, advance orders for brownies were rolling in. Sticky Fingers kept Mer busy, but it didn’t stop her from obsessing. She vented her outrage to Barb and Donald—sucking up all the air while the three of them wrapped brownies together. At night, she lay awake in bed, thinking up comebacks. Mentally, she gave him a whole different type of reading. She told herself she didn’t want to see him again. But she couldn’t leave well enough alone.

After days of stewing, she settled on a comeback she liked and wrote it on a scrap of paper: Shirley Temple didn’t become Shirley Temple Black for nothing. ’Twasn’t necessary to shoot.

Cryptic. Give him something to chew on since he was such a smart-ass. She found his car parked near his warehouse in the Mission and tucked the note under his windshield wiper.

She had meant this to be the last word between them, but a few days later, Doug called. With no mention of the note or the rude comment he’d made, he asked her out to dinner. In spite of herself, Mer didn’t turn him down.

They sat in the window seat of an inexpensive Chinese restaurant. Mer felt fidgety under Doug’s iceberg eyes. Beautiful, ethereal eyes, somehow distant. Mer ate what was on her plate—Slowly, don’t be a piggy—but didn’t take the second serving she wanted and toyed with the soy sauce and chili bottles instead as he gobbled the rest of the chicken lo mein.

They’d shared a brownie and a little coke before dinner, which made them both talkative. Mer told Doug about her travels in Europe and Morocco, how she’d nearly married a Berber. She talked about her father, the teddy-bear tough guy, her idol. She spun a yarn about narrowly escaping a gang bang in Florida, turning it into an adventure story, a laugh riot.

Doug deepened his own history in response. He came from a long line of intense female artists—his mother, grandmother, aunt, and great-aunt. His father, a brilliant navy engineer who’d taught at MIT, had died in a freak drowning accident on a salvage dive at Pearl Harbor. Doug was only five.

“I grew up fatherless,” he said, “surrounded by strong women, with no men anywhere around. Sometimes I don’t know how a man is supposed to act. I don’t always say the right thing. You might have noticed that.”

Not an apology, exactly, but Mer decided it was an attempt at one.

After his father’s death, Doug’s mother took her sons to England, where she suffered a nervous breakdown that kept her bedridden for most of a year. Unable to care for Doug and his older brother, she sent them to boarding school. “Let me tell you,” Doug said. “That place was cold on every level.” Holmewood House was a hulking, castlelike stone structure originally occupied by Queen Victoria’s gynecologist. Since Doug and his brother were in different grades, they rarely interacted. Between his father’s death, his mother’s collapse, and this final separation from his older brother, Doug’s childhood had been overwhelmingly lonesome.

Mer felt herself softening. Wasn’t everyone a little broken? Weren’t they all doing the best they could?

Art had been Doug’s refuge. “All the other boys would be out playing sports, which I never, ever did, and I’d be in the art department on my lunch break.”

Mer wasn’t a loner like Doug, but art had been her way of escaping her mother’s meanness. She’d lock herself in her bedroom and draw for hours.

Eventually, Doug had entered a fine arts program at UC Berkeley with a full scholarship. But he dropped out in 1975, months before he would’ve graduated. “I had this painting teacher who was all about modernism and understatement,” he said. “He didn’t get my work. And you know what? Fuck that. I went to the Berkeley Psychic Institute instead.”

An uncompromising artist. Finally.

“The first week I spent with your mother,” my dad says, looking back, “I did greater quantities of more kinds of drugs than I had done in my entire life up to that point. I remember coming to a point—maybe we were experimenting with brownies or something—of lying on the kitchen floor. I was totally wiped out, totally unable to stand. All I could do was lie there on the linoleum. And I was laughing, rolling on the ground and laughing with total abandon.”

They had gotten off to a rocky start, but my parents found a lot of common ground. They were both bright, sensitive, and creative, rollicking full throttle through their lives. Maybe they were too similar. As artists, they would become natural rivals, mutually inspiring but also resentful of each other’s accomplishments.

The seeds of destruction nestled inside love’s first bloom.

After dinner at the Chinese restaurant, they went back to Meridy’s flat in the Haight and had sex for the first time. It was awkward, eager, intense. They fell asleep lying side by side in guttering candlelight, the room wreathed in incense.

Mer awoke in the lightless early morning with her bed violently shaking.

“Earthquake!” she gasped, sitting bolt upright.

But the room was still. Nothing rattled; nothing toppled. Doug thrashed beside her under the blankets.

“Hey—hey, Doug!” She nudged his shoulder and found it slick with sweat. Grabbing his bicep, she tried to squeeze him awake. He made gurgling sounds, then stilled.

Was he having some kind of overdose? She flicked on her light, ready to call an ambulance, and there was Doug, expression placid, his breathing regular. She watched him swallow, his Adam’s apple sliding up his throat and back down. Sleeping like an angel.

“Hey, Doug, you okay?”

He murmured and rolled away toward the wall. She watched him for a while, then clicked the light back off and pulled the covers up to her chin. The sheets were soaked with cooling sweat. She didn’t sleep again until sunrise.

Over coffee that morning, Meridy waited for Doug to mention something—anything—about the night before, but he seemed mysteriously detached. He sat at the kitchen table flipping through a book of Aubrey Beardsley prints. Mer’s attempts at conversation fell flat. Typical, she thought. Wham, bam, freak out in your bed, thank you, ma’am.

Donald padded into the kitchen for his morning coffee. Seeing Doug there, he smiled knowingly. “Good morning, you two. Nice night?”

Mer narrowed her eyes at Donald. He pursed his lips and took his mug to his room.

“So . . .” Mer ventured. “You slept really rough. You were kind of kicking in your sleep. Did you have a bad dream?”

Doug didn’t respond at all, apparently too absorbed in the book.

“Hey, hello there, Doug.” His eyes snapped into focus. “You were kicking in your sleep. Seemed like you had a bad dream. Is everything okay?”

“I’m fine,” he said with complete nonchalance. “No dreams I remember.”

Men could be so damned cold. The night suddenly seemed like a mistake.

But Doug warmed up after coffee and a joint. As he prepared to leave midmorning, he planted a sweet-enough kiss on Mer’s lips to make her feel floaty throughout the day.

Not until late afternoon, when the smell set in, did she realize that he had urinated in her bed.