KILL FAGS! DAN WHITE FOR MAYOR! Sprayed in foot-high lettering on a wall by Dolores Park, the graffiti stopped Mer in her tracks. Early 1979: a new world, a dark gray day. Closer to Castro Street, she saw FREE DAN WHITE! in the same rough scrawl.

The dismay must have shown on Mer’s face when she ducked into Main Line Gifts on Castro Street.

“Like the new mural?” her customer Roger said.

“Why do people have to be so ugly?”

He smirked. “We had the bigots scared for a while, but they’re getting frisky again.”

Mer knew homophobia existed in San Francisco, like everywhere else in America. But when your social circle was an echo chamber, you could pretend. Easy to imagine this pretty city as a bubble floating above ignorance and intolerance. Dan White might have acted alone like the papers said, but he wasn’t alone in his hatred. A whole side of San Francisco that Mer had barely noticed before—old-school conservative, morally outraged—was showing its teeth. People who’d been disregarded, first by a hundred thousand or so hippie kids, then by a hundred thousand or so gays and lesbians.

Roger twirled the metal police whistle he wore around his neck. “Fashion statement of the season.”

On Castro Street, people talked about the uptick in violence: brutal attacks in alleys; police harassment in lesbian and gay bars under flimsy pretenses; teens prowling in muscle cars, throwing garbage and picking fights. There were articles about it, and not only in the gay press and local papers; the Washington Post ran a piece under the headline, ANTI-GAY SENTIMENTS TURN VIOLENT IN AFTERMATH OF MOSCONE-MILK KILLINGS.

Mer might not have known that in the weeks following the assassinations police and firefighters had jointly raised $100,000 for Dan White’s defense. Or that White had been greeted with a friendly ass pat when he turned himself in at Northern Station, as if he were a baseball player returning to the dugout after a home run. Or that some cops had sung “Danny Boy” over the police scanner when the assassin’s identity was revealed. Or that the officer who’d taken White’s confession had known him since grammar school and softballed the interrogation. But she could see that her friends were scared.

Roger bought two dozen brownies. Looking at the bag design, he scrunched his forehead. “Is everything okay with you?”

It was one of Doug’s bags: a furiously scribbled drawing of a woman (obviously her) and a man (obviously him) facing away from each other with a malevolent demon sneering between them, and the words, It’s Not Me, It’s My Brownie.

Mer shrugged it off—“The joys of marriage!”—and continued on her way. Everything wasn’t okay, but she’d rather not advertise it. Unlike Doug, apparently.

He’d been going off his Dilantin again. Mer had woken up after midnight to an earthquake—no matter how many times it happened, it always felt like a goddamn earthquake. Realizing it was another seizure, she’d forced her arm under Doug’s jolting body and rolled him onto his side to prevent choking. The commotion woke the toddlers, who both started howling. Then the whole household was up. Mer had spent the morning bringing Doug cold washcloths for his headache while he vomited brown bile.

She wished episodes like this would keep him on his meds. Doug would take his Dilantin for a while, then secretly taper off again. Always testing, trying to prove he had the power to control his own epilepsy.

They fought about that. And about the ten pounds Mer couldn’t seem to lose, and the ledgers Doug insisted on keeping, and music and movies and art and their friends and pretty much everything else.

Mer was wearing an outfit inspired by Han Solo from Star Wars—khaki vest, black blouse, harem pants, knee-high leather boots, and a black beret. A militant look, but it suited the gunmetal weather. And her mood. She’d decided to do her run alone that afternoon—easier to negotiate stairs and tight spaces without a stroller—but she missed the guileless joy. The duffels of brownies seemed to weigh two tons as she trudged to her next stop. Boys were still cruising at Hibernia Beach, but there was a singed, burned-toast vibe.

The neighborhood seemed somehow stripped of its innocence. Because even in its most hard-core sexuality—the relentless cruising, the bathhouses and sex clubs, the orgies her friends told her about, even the S & M scene that Mer never quite understood—something about it had always seemed gleeful and immature, like teenage lust. Adding grief to the equation made the bawdiness so . . . intentional, like people were trying too hard to have fun.

Early 1979 clicked by with mounting tension, like a roller coaster climbing the first incline before the inevitable plummet and loop the loops. As anger and frustration intensified at the warehouse and in the City at large, so did the frenetic partying.

The photos of the Sticky Fingers crew from this period reveal a shift in attitude. The flamboyance rocketed into outer space. Especially in shots of my dad, whose outfits became dares. One week, he wore elaborate black eye makeup, shiny red spandex pants, and a women’s red satin blouse open to his navel and cinched at the waist. The next week, Stannous Flouride helped him dress up as a punk in torn slacks, plaid jacket, black nail polish, and a fake bloody wound on his face so he could experiment with nihilism for a day. Another week, Doug imitated the Chicano men he saw in the Mission wearing high-waisted black pants, a white wifebeater, and a panama hat. On the bus to Noe Valley, the dirty looks he got from real Chicanos convinced him never to try that again.

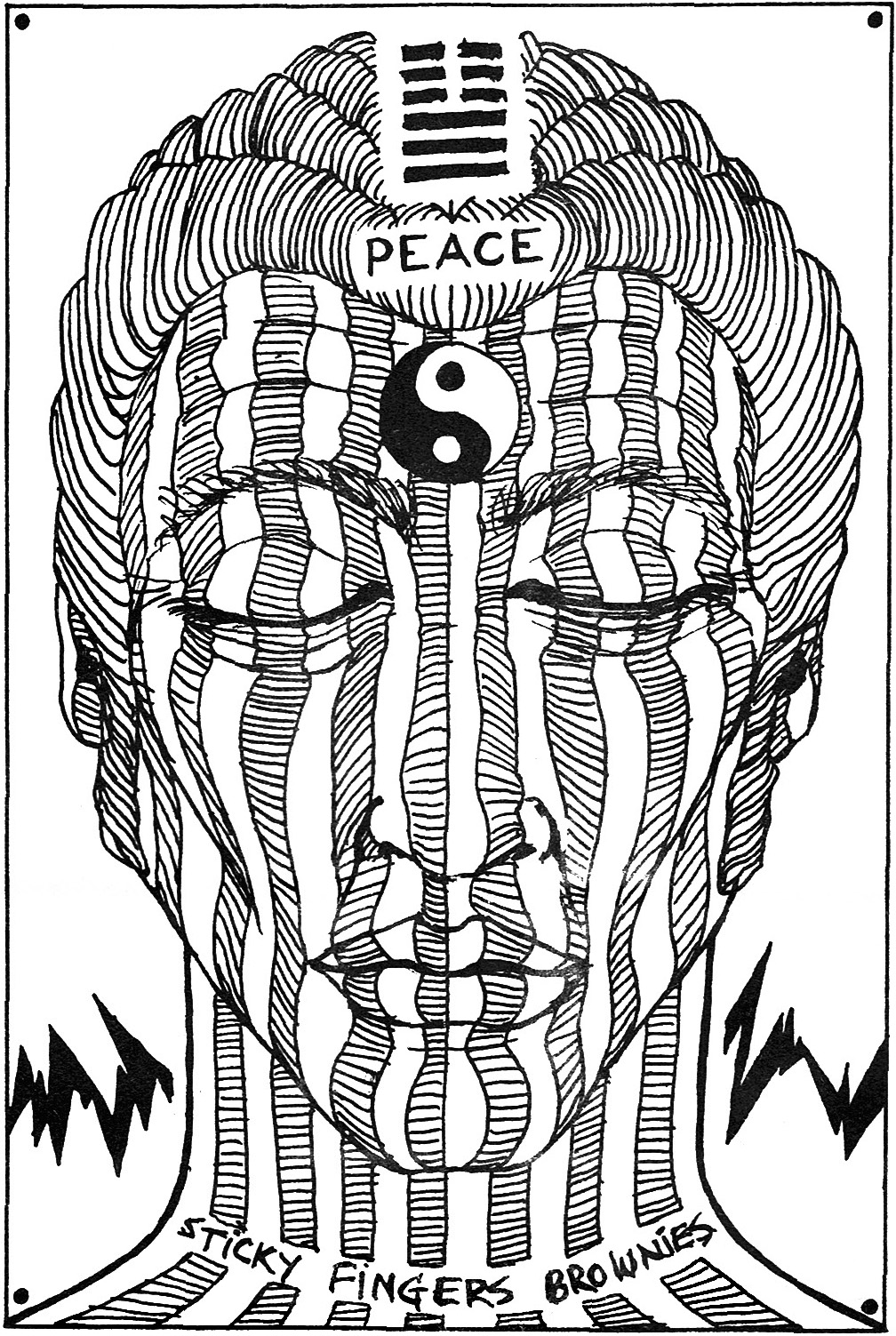

One Saturday, Stannous accompanied Doug on a sales run. Doug wore white martial-arts pajamas with his skin and hair painted entirely white so he appeared to glow; Stannous wore all black, with face paint and mirrored sunglasses. They sold brownies in those getups: the silent wraith shadowing the movements of the shining man.

Even in San Francisco in the seventies, where fashion sometimes verged on costume, this would’ve raised eyebrows. I appreciate that my dad saw his sales runs as performance art. But from my distance of decades, I feel like I’m seeing him begin to slip, his grip on reality loosening. The bags he designed became stranger. One featured a nude man ripping his chest cavity open, spraying blood in all directions. The heart is an organ, too, it read, so why not let it breathe?

For the vernal equinox on March 21, my dad proposed a party to celebrate the rebirth he hoped would follow a winter so marked by death. San Francisco had been vanquished before in earthquakes and fires. Each time, the City had risen from its own ashes, renewed. The phoenix was a bird that combusted whenever it sensed death approaching; a new phoenix always rose from the ashes. It was the symbol of San Francisco, the image on the municipal flag.

He and Mer choreographed a dance together, fusing her jazz moves and his modern moves, their styles not parallel but intersecting. Five women would represent fire. Four men would embody the smoke and ashes. Doug would be the phoenix. Together, they’d perform a rite to welcome the cycle of new life that would accompany spring. They called it Phoenix Rising.

Of the friends they recruited to perform, not one of them was a trained dancer.

Stannous and Doug dressed to sell.

The memory makes my mom laugh. “John Battle was even in it, that oaf. He was gigantic and a total klutz. And we had him, like, leaping all around. Hundreds of people came to this party. I don’t know what we were thinking.”

I was too young to remember Phoenix Rising, but part of me would sacrifice a lesser tooth to see a video of my parents and their friends—not a serious dancer among them—pretending to be fire birds and flames and raining ash.

In the wee hours of March 31, the dregs of a bachelor party showed up at a low-key lesbian dive in the Avenues called Peg’s Place. According to a firsthand account published in the Bay Area Reporter, some of the eight or so men arrived carrying open beers, so the female bouncer denied them entrance. When the men tried to muscle past her, she yelled for the bartender to call the cops.

“We are the cops,” one of the men said. “And we’ll do as we damn well please.” He hit her in the chest. Someone in the group yelled, “Get the dykes!” as the men forced their way into the bar. One guy put the bar’s owner—a woman who was already disabled from a back injury—in a choke hold; she was later hospitalized. Another guy clobbered the bouncer’s head with a pool cue.

Two of the brawlers turned out to be off-duty police officers. The women tried to press charges, but no arrests were made.

Dianne Feinstein was so slow to discipline the rowdy police that she lost credibility with many in the lesbian and gay communities. Some were already upset because she’d been sluggish about filling Milk’s seat and had bypassed a neighborhood favorite, Harvey’s former aide and campaign manager, Anne Kronenberg. And Feinstein had won herself no friends by telling the Ladies’ Home Journal, “The right of an individual to live as he or she chooses can become offensive—the gay community is going to have to face this.” DUMP DIANNE T-shirts and pinbacks became a fad. Meanwhile, rumor had it that some cops wore FREE DAN WHITE shirts under their uniforms, as if this were a secret superhero identity.

Cleve Jones was in a bar on Castro Street when half a dozen cops came in, demanded IDs, and roughed people up, apparently for kicks. Shortly thereafter, Cleve was sitting on his own stoop in the middle of the day when an officer strolling by whacked him on the shin with a billy club, “Get moving.”

“I live here,” Cleve said, rubbing his leg.

“I told you to get moving.”

Cleve headed inside and locked the door behind him.

Dan White consumed the news throughout spring. The defense was wily and innovative; the prosecution was weirdly limp—hobbled by politics (including District Attorney Freitas’s unflattering ties to Jim Jones). Before being selected as prosecutor, attorney Tom Norman allegedly commented to a colleague that he hoped he wouldn’t be assigned to the city hall murders because he felt sorry for the accused. White got an entirely heterosexual, predominantly white Catholic jury, one of whom was a retired cop, and half of whom lived near the area where White had grown up—the demographic most likely to share his frustrations over what he called “radicals, social deviates, and incorrigibles.”

The open-and-shut case grew slippery. To get first-degree murder convictions, the prosecutor had to prove that White had acted with premeditation and malice aforethought. But instead of laying out that crucial angle, Norman belabored ballistics and other details of the killings that weren’t even being disputed. Homophobia was never discussed in court nor was the political jockeying between Milk and White. Both issues could have been used in a malice argument but not without exposing broader corruption within city government and law enforcement.

Some mainstream reporters took pains to describe White in sympathetic tones, waxing at length about the loss of his father at a young age, his athleticism in school, military record, heroism as a former firefighter and police officer, and his devotion to family—while managing rarely to mention the wife and four children mourning Moscone or the vast community grieving for Milk. Toward the end of the trial, one reporter for the Sunday Examiner & Chronicle went so far as to conclude that “there were three victims of the terrible events in City Hall Nov. 27: George Moscone, Harvey Milk, and Dan White.”

Even so, Mer felt sure that the only real question was whether Dan White was going to get the death penalty (which he, ironically, had helped reinstate for crimes like his in California) or life in prison. Because how could someone—anyone—walk into city hall in broad daylight, execute two elected politicians, boldly confess to pulling the trigger, and not spend the rest of his days behind bars?

Tension was ratcheting up. At the same time, spring of 1979 saw some of the decade’s most opulent parties as well as an obsession with all things shiny and gold. The Treasures of Tutankhamun would come to San Francisco’s de Young museum in June, drawing record crowds and becoming one of the most popular exhibits of all time. The hoopla started months in advance: there were movies, camp theater, and academic seminars; fashion leaned heavily on draped fabric and gold serpent bracelets; a new seventeen-scene Egyptian exhibit opened at the Wax Museum at Fisherman’s Wharf. In April, Barb landed a gig costuming an elaborate Egyptian-themed benefit for Children’s Hospital, a spare-no-expense, gala-cum-all-night-disco extravaganza.

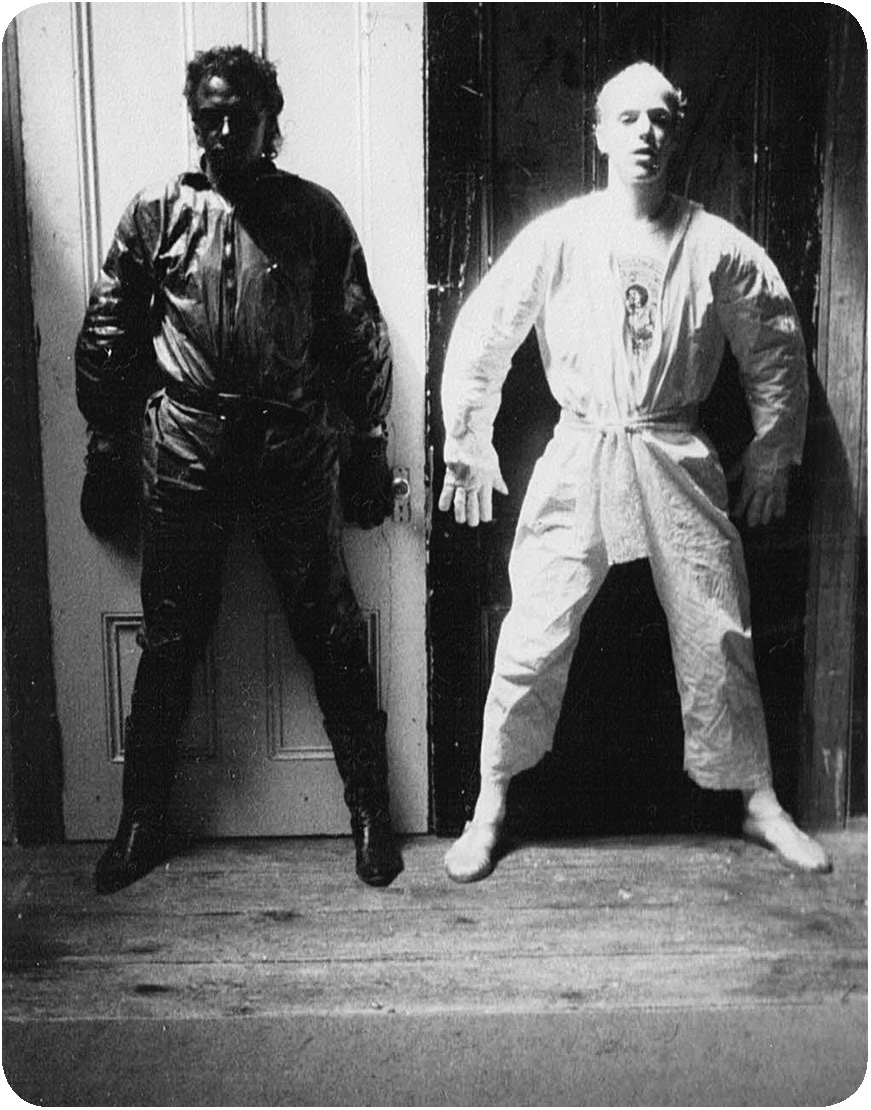

To costume the event, Barb rented pieces from the American Conservatory Theater and created others out of gold lamé, painted leather, beads, and glass gemstones. Cyril Magnin, the elderly magnate behind the I. Magnin department stores, embodied the pharaoh perched on a golden throne borrowed from Twentieth Century Fox. To portray the pharaoh’s royal court, Barb recruited the Sticky Fingers crew; Doug, Mer, Cheryl, Carmen, and Susan appeared dripping in gold jewelry and wrapped in muslin. Even the brownie babies—Noel, Marcus, and I—shuffled around in tiny white togas and little headdresses.

Camels were hauled in from Marine World/Africa USA to roam the dance floor along with pythons and brightly plumed parrots. There were live bands and deejays, belly dancers, and hors d’oeuvres sprinkled with flakes of real gold. Sand dunes and statuary flanked the entrance of the South of Market Galleria event center. It was a high-society ball straight from the satirical “Tales of the City” column.

Cultural insensitivity abounded: heavy brown bronzer and thick black eyeliner was fair game for an “Egyptian look,” and blonde toddlers in togas could belong to the royal family of a nation on continental Africa. No one worried about the mental health of live camels forced to prance around a crowded disco with flashing lights and pounding music. All of it done in the name of something so unimpeachably respectable as children’s health care. There was, perhaps, a hint of desperation in the extravagance, as if people sensed they’d better get their kicks while they could; the seventies were ending.

Sticky Fingers kids, left to right: Noel, Alia, and Marcus.

And there we were, interlopers from the fringe of society. My parents were in orbit, their kohl-ringed eyes bulging from cocaine. Old Cyril Magnin surveyed the revelry from his golden throne.

Mer drew a king on a throne. In his right hand, a sword. In his left, the scales of justice. With a verdict on Dan White expected any day, she based her brownie bag for May 18 on the tarot card Justice.

She thought closure would do everyone good. The assassinations had revealed festering ugliness; it was as if a rock had been moved, exposing a world of creepy crawlies. She hoped they could kick some dirt over it and move on.

The verdict landed like a fist to the jaw at 5:28 p.m. on May 21: two counts of voluntary manslaughter carrying a maximum sentence of eight years. With good behavior, Dan White could be free in under five years.

“Lord God,” White’s defense attorney had said in his closing statement. “Nobody could say that the things that were happening to him wouldn’t make a reasonable man mad . . . A good man, a man with a fine background, does not cold-bloodedly go down and kill two people. That just doesn’t happen.” White was simply an earnest, patriotic San Franciscan who’d been pushed too far by conniving liberals, lost too much sleep to depression, and, yes, ate too much sugar. Anyone in his position might have done the same.

Contrary to popular belief, the defense hadn’t argued that overdosing on Twinkies had driven Dan White insane. His plea wasn’t one of insanity, but rather that he’d suffered a brief period of impairment caused by long-term undiagnosed depression and insomnia. Eating sugary food was held up as a symptom of his malaise (not the cause). But some clever journalist coined the term “Twinkie Defense,” and it caught on. The voluntary manslaughter conviction was so improbable given the facts (the deliberate reloading of his gun before killing Milk, for example) that you might as well blame it on sugar.

James Denman, the undersheriff who held Dan White during the seventy-two hours after his arrest, described his prisoner to journalist Warren Hinckle as “perfunctory and businesslike” and without an “iota of remorse.” And when the supposedly impaired White entered the state prison in Soledad to begin his sentence, the psychiatrists who examined him decided against prescribing therapy, finding “no apparent signs” of mental disorder.

Cleve was in his apartment when a city hall reporter called. He stretched the cord of his kitchen phone into the bathroom and closed the door for privacy. When the reporter told him the verdict, Cleve leaned over the toilet and puked.

“Are you there?” the reporter asked. “Do you have anything to say?”

He wiped his mouth. The verdict had shown Cleve that the justice system wouldn’t protect even the most powerful among them. “This means that in America it’s okay to kill gay people,” he said.

Cleve’s roommate pounded on the door to say that lesbian activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon were waiting in front of the Twin Peaks Tavern with some reporters. Cleve grabbed his jacket and ran downstairs for an impromptu press conference.

A local TV news reporter said, “You have a permit to close Castro Street tomorrow to celebrate Harvey Milk’s birthday. Is that when the community will react to this verdict?”

Cleve looked dramatically into the camera. “No,” he said. “The reaction will be tonight. It will be now.”

Days before, Cleve had walked down to the Mission Station with two other activists to warn the SFPD that if Dan White got off the neighborhood was going to explode; they should prepare for a riot.

“You people aren’t really violent,” Captain George Jeffries told him. “If a crowd gathers, you’ll march them down Market Street like you always do.” The captain’s smile was so condescending that Cleve thought he might get a pat on the head.

Now the scenario Cleve had predicted was underway. He ran back to his flat to get ready. Paramount in his mind was something Harvey had said in the lead-up to the Briggs vote: “Don’t burn down your own neighborhood.” He’d taken note of the destruction in Watts and other black neighborhoods after Dr. King was assassinated. “If there’s going to be a riot,” Harvey said, “take it downtown. Burn the banks. Don’t let it happen where we live.”

Cleve grabbed his jacket and a bullhorn Harvey had given him. By the time he got back on the street, hundreds of people had already gathered in the intersection.

Doug and Mer consulted the I Ching about joining the protest that night, but the hexagram warned of violence and possible bloodshed; with a baby to protect, they decided to sit this one out. Later, at about ten that night, Barb called the warehouse. “They’re rioting at city hall. It’s on the news.”

Some five thousand people had marched to Civic Center chanting, “Dan White was a cop!” and “Avenge Harvey Milk!” Chief Gain—the Moscone appointee who’d had the police cruisers painted baby blue—ordered his men to hold their ground without using force against the protesters, a stance many of the rank and file resented. This would later cost the chief his job; the San Francisco Police Officers Association would vote “no confidence” in Gain the following month, and Feinstein would eventually give in and appoint a good old boy who would promptly repaint the squad cars black and white.

The crowd broke through police lines, tore the elegant ironwork off the doors of city hall, and used it to break windows. They set dumpster fires and trashed nearby buildings. Police attacked with tear gas and batons, while rioters threw rocks and bottles. Several policemen had to be rescued after getting trapped inside city hall when the crowd surrounded the building. By the end of the night, twelve squad cars had gone up in flames, their melting sirens moaning like wounded animals.

Reporter Warren Hinckle was on Castro Street when rogue squad cars rolled up: “They came in marked cars, first in twos, then in threes,” he wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle. “The cars were sardine-full of cops; three in the back seat, sometimes three in the front.” Never mind that many of the people who’d stayed in that neighborhood were the ones not rioting at city hall. Officers were heard yelling “Banzai!” as they charged into the Elephant Walk—one of Mer’s regular brownie stops and a favorite performance venue of Sylvester’s. Cops bludgeoned patrons and employees, broke windows and chairs, and shattered the artful elephant-motif stained glass, raining shards onto those cowering behind the bar. As one bar patron who was hospitalized with five broken ribs and a partially collapsed lung commented later, “They were down here to crack a few heads open.”

A former police inspector who’d tagged along with Hinckle that night found Captain Jeffries directing troops, and confronted him: “It was all quiet before you sent these guys in here. You’re provoking these kids and putting a lot of cops in danger. What kind of police work is this?”

“We lost the battle at city hall,” the captain snapped. “We aren’t going to lose this one.”

Patrolman Jerry D’Elia, a single dad, had just come home to his kids after a long day on Muni transit detail when the call came in to go back on duty. D’Elia assumed it was a prank and hung up. The dispatcher called back and explained that there was a problem with the White verdict and that all hands were needed. They had even put out a mutual aid request for surrounding counties to send available officers.

By the time D’Elia got to Castro Street after putting his kids to bed, the melee had escalated. Police were getting pelted with beer bottles and debris. D’Elia wasn’t close enough to the Elephant Walk to see what happened there. “But tensions were running pretty high by then,” he says, thinking back. “The cops were really heated because Gain muzzled everybody. We were a really well-trained big department and he wouldn’t let us clear the streets or anything. So once that happened—once they knew we weren’t going to do anything—well, we kind of became piñatas for them.”

D’Elia joined a skirmish line on Market Street. He remembers glancing down the line and seeing a group of Castro guys poking his deputy chief in the chest, and saying, “You take one more step . . .” At another point, he struggled to process a surreal vision of flaming car tires rolling downhill toward him and the other police.

At about two in the morning, D’Elia and some of his colleagues decided of their own volition to disperse. “We were so disgusted, we left,” he says. “Just one by one, the whole thing dissolved. We didn’t cross their line and I guess they got tired, too. Everybody went home to fight another day.”

Most news outlets reported that sixty-one police officers and more than one hundred civilians were injured that night. The Police Officers Association claimed it was the other way around, with twice as many cops hospitalized as civilians. Either way, people got hurt.

When Dan Clowry got to work the next morning, he was stunned to see the Elephant Walk’s windows boarded up and glass all over the sidewalk. He had marched to city hall with everyone else but left when things started getting broken. One of his regulars came in for coffee after being released from the ER. He had pins in his arm from getting whaled on with nightsticks. “They beat him into a corner,” Dan recalls. “And then they beat him some more.”

Mayor Feinstein thought the manslaughter verdict was a miscarriage of justice, but she could not abide rioting. She gathered prominent gays and lesbians in her office the next morning. Permits had already been issued for a street party to celebrate Harvey Milk’s birthday later that night. According to Cleve Jones, Feinstein had assembled them to explain her decision to summon the National Guard. Convinced that this would only escalate violence, he dissuaded her by lying. “I have five hundred trained monitors ready to keep the peace on Castro tonight,” he bluffed. “If you keep the police away, there will be no violence.”

The fib worked. Activists spent the day teaching last-minute volunteers how to monitor a crowd. They planned escape routes in case people needed to scatter. Finally, Cleve marshaled the ultimate peacekeeping weapon: he asked Sylvester to perform.

That night, some people showed up for the celebration wearing helmets and carrying baseball bats. The mood was tense. But when Sylvester started to groove, the crowd got high and danced in the street. The cops maintained their distance, and no harm was done.

At one point, someone in the crowd burst out screaming, “He’s dead! He’s dead and he’s never coming back!” People surrounded and embraced the man, holding him as a group, while Sylvester led the crowd in singing “Happy Birthday” to Harvey Milk.

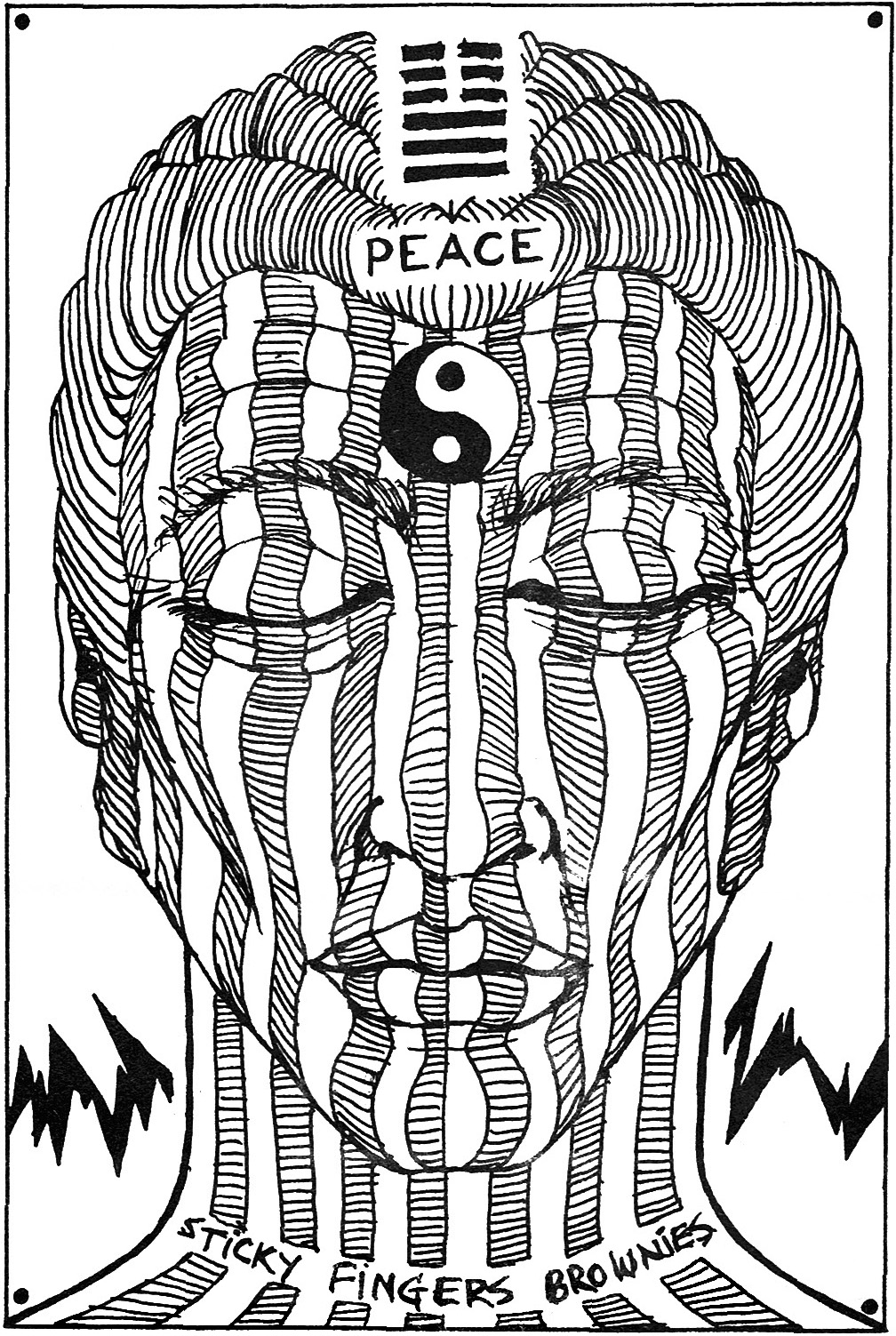

When Mer did her run later that week, some businesses were still boarded up. People wore their injuries like badges of honor. Doug had designed a beautiful bag that week: a Buddha-like face in meditation, with the I Ching hexagram “11. T’ai/ Peace” on his forehead. Mer thought Castro Street looked more like a war zone.

New graffiti in the neighborhood struck a different chord than before. One wall read, DAN WHITE & CO. YOU WILL NOT ESCAPE, FOR VIOLENT FAIRIES WILL VISIT YOU EVEN IN YOUR DREAMS.

“We were swaggering,” Cleve says about the mood following what became known as the White Night Riots. “Yeah, we were swaggering.” He brings up something Allen Ginsberg told the Village Voice after the 1969 uprising at the Stonewall Inn: “They’ve lost that wounded look that fags all had 10 years ago.”

The cops didn’t come around so much after that.

As 1979 careened into summer, Sticky Fingers reached a degree of notoriety that sometimes unnerved Mer. Everyone seemed to know who they were, and thanks to the raucous costume parties and Cheryl’s Friday-night warehouse sales, a growing number of people also knew where they operated.

Early June, one of Mer’s wharf customers told her that the extra brownies he was buying were for a friend heading to the SALT II talks in Vienna; he planned to smuggle them in his suitcase. Another customer said that the famed columnist Herb Caen was purchasing brownies through a friend. “Cool,” Mer said. “So long as he doesn’t put us in his column.”

Sticky Fingers had been courted by writers—one who wanted to include the Brownie Ladies in a book on iconic San Francisco women—and a few journalists hoping to write articles, but the hexagrams were never right, so the brownie crew demurred.

A photojournalist named Laurence Cherniak convinced them to reconsider. He had some impressive bona fides—like founding what was probably the world’s first head shop in Toronto in 1965 (predating San Francisco’s legendary Psychedelic Shop by several months). Cherniak also marketed his own line of purple-and-red-speckled rolling papers, which were popular then. He’d been documenting hashish production worldwide since the 1960s, and his sensual images often graced the pages of High Times. Now he was launching The Great Books of Hashish, the first in a planned trilogy to be published by And/Or Press in Berkeley. The first book focused on the Middle East, but the second one would include a section on the United States, and Laurence’s editor sent him to find the famous Sticky Fingers Brownies.

Dennis Peron made the introduction. Cherniak was handsome and loquacious, with a shock of dark hair and olive skin. He promised to refer to Sticky Fingers only by their business title and exclude personal information and identifiable photos. He came to the warehouse bearing an astounding hunk of opiated Nepalese Temple Ball hash to share.

As usual, hexagrams had the final say. This time the oracle gave a green light.

Between June and August 1979, Cherniak hung around the warehouse, photographing the baking process. Mer even brought him along on a Saturday sales route.

“They were producing thousands of brownies at that time,” Cherniak says, looking back. “And I remember standing over the warm stove as the butter was melting, and then stirring in the cannabis and carefully mixing each ingredient in. How much care went into each stage of preparation. So when we carried the brownies up to the twentysomething floor of the Transamerica building to deliver them, that love was present. I saw the joy and gratitude come over the faces of their customers, who returned that love. That’s what it’s all about.”

When I ask Laurence if, in his extensive travels through the underground cannabis world of the 1970s, he ever encountered an operation like Sticky Fingers—either in scope or in the relationship they had with their community—he doesn’t hesitate. “Absolutely not,” he says. “If it wasn’t happening in California, it wasn’t happening in the United States at all. This was where it was revolutionary. That’s why I came several times to photograph the process. And why I have that wonderful picture of you in my book.”

The picture Laurence is referring to appears in The Great Books of Cannabis, his second volume, which begins with a preface by Timothy Leary. You see a pan of gooey, freshly baked brownies along with a brick of weed, a small pile of homegrown, an array of wrapped brownies, and—invading one corner of the frame—my blonde head and one curious blue eye staring straight into Laurence Cherniak’s lens.