Doug dreamed of an earthquake. Crevasses opened in city streets. Buildings collapsed, sending dust plumes into the sky. A gleaming tidal wave reared so high that the Transamerica Pyramid looked like a child’s toy. People swam in water poisoned by their own sewage. There would be famine because we’d forgotten how to grow food, disease because too many people lived in close proximity. Waking up, he thought, Mother Earth is pissed. And we had better be ready for her wrath.

To survive our karma, mankind would have to return to simplicity. Go back to the land, restore harmony. The meltdown at the Three Mile Island power plant in Pennsylvania that March should have been a wake-up call. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory was a mere fifty miles from San Francisco. What sort of fools built a nuclear weapons research facility on a major tectonic fault?

Doug had recently seen in an article that major earthquakes came in cycles of roughly eighty years. The 1906 quake had hit seventy-three years ago. Sometimes Doug felt like the only lemming in the pack to look around and say, Hey, guys, isn’t that a cliff up ahead?

The big one was coming. Doug did not want to be in a crowded city when it hit.

“The big one is always coming,” Mer argued, exasperated. “You’re just freaked out because you had a seizure. And if you would take your damn Dilantin like you’re supposed to, this wouldn’t happen so often.” They were having coffee in the kitchen. The kids were playing with a Playskool vacuum that sounded like a cross between a popcorn maker and a machine gun.

“It’s not the fucking epilepsy,” Doug countered. “People aren’t supposed to live piled up on top of one another.”

Maybe Doug didn’t see the pattern, but Mer did. He’d have a grand mal seizure in bed, and in the days and weeks that followed, his dreams would become apocalyptic. Even when he wouldn’t admit he’d had an attack, she could tell from his behavior. The spaciness, the brooding, the scary pronouncements.

Doug talked about “getting out of the rat race” more and more since they’d been making trips to Willits. Mer could see that he loved it up there, how he relaxed and brightened. Maybe it would be good for their marriage to get Doug away from the pressures of city life. It could be good for raising a child, too. Open fields, blue skies, and all that.

But Mer wasn’t a country girl.

“Look,” Doug said. “Maybe you think earthquakes are no big deal because we’ve been through a couple of shakers. But we haven’t seen shit. Tens of thousands of people are going to be wiped out by what’s coming.”

Mer didn’t know what to think. Sure, there could be a big earthquake. But was that a reason to move? You didn’t leave Hawaii because there might be another tsunami. You didn’t abandon Kansas because your house could get picked up in a twister. Doug was psychic but not infallible. Were the apocalyptic dreams fears? Hopes? Visions of the future?

Mer, meanwhile, had been having nightmares about a bust: police kicked down the door while Carmen baked and the Wrapettes gossiped at the table; three cops dressed all in black slipped in like ninjas during the night to steal Doug’s ledgers; a customer reached into a pocket for money and instead came out with a badge. There were dreams of losing her family. Dreams that ended in prison.

Early July, Dan Clowry at the Village Deli told Mer about an unsettling incident at the café. An unfamiliar man had come to the counter and ordered a brownie. Dan put a regular chocolate brownie on a plate for him.

“Don’t you have magic brownies here?” the guy said.

Dan feigned surprise. “Gosh, not that I know of! We’re just a café.”

The guy blinked pointedly, paid for his unmagical brownie, and ate it on the way out the door.

“I don’t know why,” Dan told Mer. “But I knew he was police. Anyway, he wasn’t one of us.”

As usual when anxiety kicked in, Mer lay on the barge in her room and tossed hexagrams. What is my inspiration for this week’s brownie run? and What are the effects of continuing to sell at the Village Deli? Indications were all right, so she sallied forth.

Now that Mer was no longer breastfeeding, there was more blow in the house—and that bothered Doug. Not just for occasional parties anymore, but for the pre parties and post parties and between parties. The ladies would bring stuff home from their brownie runs. Look what so-and-so traded me!

On coke, Mer and Cheryl buzzed with ideas and humor, but the drug had a stiffening effect on Doug. It left him stressed and edgy, electricity fizzing in his brain. Late one night, he blew his nose in the bathroom and saw red streaks on his handkerchief. Suddenly, blood gushed from his nose down over his mustache and lips. In the bathroom mirror, his face looked drawn and somehow jagged. He heard Mer and Cheryl cackling uproariously in the kitchen, and thought, This is not my divine path.

Thereafter, he worked against party plans—which made him the bad guy.

Once, he came home to find Mer giggling hysterically on her bed with some flaming gay guy Doug didn’t even know. Doug thought, Why the fuck is this man in bed with my wife? He knew she wasn’t cheating, but it chafed him to see her in tears of laughter with a stranger while their own conversations drifted into frequent arguments, the joy draining out of their shared life.

Doug sealed himself behind the copper doors of his studio. His paintings came slowly, laboriously. Art, for him, was about revealing paths toward enlightenment. The message had to be perfect. Sometimes he’d cover an inch of canvas in a whole day. Sometimes all he did was undo his work from the day before. Sometimes all he could do was think.

Meridy, on the other hand, turned out drawings and paintings in a kind of ecstatic frenzy. She didn’t have her own studio but worked wherever, whenever. If she didn’t work, she became touchy and overwrought; but as long as she applied pigment to a surface, she seemed pleased with herself at the end of the day. It was all so easy for her.

Summer 1979, a book came out that would have a major impact on my dad’s life. To this day, he keeps a copy prominently displayed on his bookshelf: Sexual Secrets: The Alchemy of Ecstasy. The spine is cracked, pages worn from being referenced repeatedly over the years. (I remember this book being around throughout my childhood; our copy bears crayon marks from when I colored a detailed drawing of a blow job in grass green.)

Sexual Secrets is a compendium of sex and mysticism rooted in Eastern traditions. The jacket copy describes it as the “distillation of more than two thousand years of practical techniques for enhancing sexual awareness and achieving the transcendental experience of unity.” The author, Nik Douglas, had studied for eight years in the Himalayas and did many of his own translations from Sanskrit. The text—scholarly, dry, research heavy—appears alongside hundreds of original illustrations by collaborator Penny Slinger as well as reprints from pillow books and sacred texts.

The book was an instant hit among spiritual seekers like my dad. I imagine him reading it in the armchair in his studio surrounded by his own paintings, which incorporated symbols of Hinduism, Taoism, Tantra, and Native American religions. Not just paging through the erotic drawings but carefully reading the text. How spiritually serious he was, how sincerely he wished for enlightenment.

I envision him arriving at page 336 and beginning the section “Male Homosexuality” with a mixture of trepidation and thrill.

Nik Douglas depicts homosexuality as a perversion of the natural balance between masculine and feminine energy—an abomination. He claims it’s the negative result of aggressive copulation between the parents, an unhealthy pregnancy, or a childhood without male role models. The author describes gay men as having the “hormonal chemistry and minds of women” and anal sex as “unnatural, unhealthy and potentially damaging to the psyche.” He waxes at length about various religions that have condemned homosexuality for one reason or another.

He also argues that flourishing homosexuality has preceded the collapse of several world civilizations. “An excessively homosexual society will quickly annihilate itself,” he writes. “No amount of theorizing can alter this fact, which has been demonstrated throughout history.”

Toward the end of the section, he lays out “practical techniques for overcoming the wiles of destiny,” which include yoga postures, breathing, and meditation. “Tantra teaches that when the creative attitude is brought to bear on any problem, there are no obstacles that cannot be overcome.”

This doesn’t sound any healthier or more feasible to me than Christian-based conversion therapy. I imagine these words entering my dad’s consciousness and doing their work there, making him ashamed and also strengthening his resolve to change his nature by force of will, to cleanse himself.

Maybe that’s why he decided to confess.

He told Cheryl first.

Doug doesn’t remember this moment, but Cheryl does. They were in the baked-goods aisle of Cala Foods buying brownie supplies when Doug brought it up. “I have to tell you something.”

Cheryl thought, Uh-oh.

“Remember how I was so sure Alia was going to be a boy?”

“Oh, yeah,” she laughed. “You were convinced.”

“Well, I kind of freaked out when things didn’t go the way I expected. And I left the hospital and I went to a bathhouse . . . you know, to be with men.”

Cheryl eyed him sideways. “I don’t know why you’re telling me this.”

“Because I think I should tell Meridy. It was wrong, and I need to come clean.”

“No. Doug, you do not have to tell Meridy. What is that going to accomplish? You two fight enough already.”

Doug squinted at her, head slightly cocked.

“We need butter.” Cheryl turned and moved quickly toward the dairy aisle in the too-bright store.

He did tell Meridy. Not gently or carefully but in the middle of a fight about something else.

She was dumbfounded. She’d suffered through thirty-two hours of labor, merciless contractions, and slicing and dicing, and he’d taken that opportunity to indulge a fantasy. “You were out screwing some guy?”

“I didn’t have intercourse if that’s what you’re asking. But I did do other things.”

The shock gave way to rage. Though six inches shorter than Doug, she stood on her toes to get up in his face and yell at the top of her lungs. At some point, Doug tried to shoo her away. She turned toward him, and the flat of his palm accidentally whapped the side of her head. Mer felt a sharp pain deep in her ear followed by a rushing sound like television static.

“What the fuck did you do?” she wailed, and there was something wrong with how the words sounded inside her head. Cottony. Smothered. Like someone wanted to hush her with a shh in her ear.

A General Hospital ER doctor confirmed that Mer’s eardrum had ruptured. He referred her to a specialist who patched the tear, warned her to avoid airplanes and water for a while, and sent her home. It healed within a couple of weeks, no infection or permanent damage.

In the aftermath, Doug was contrite and ready with promises. They had long-overdue heart-to-heart talks.

“So,” Mer asked quietly. “Are you gay?”

“No,” Doug answered firmly. “I am definitely not gay. I’m attracted to women.”

Mer might have preferred to hear I’m attracted to you, but he kept going and she listened.

“In Sexual Secrets, they talk about what can cause a masculine-feminine imbalance. One of the main things is growing up without a father. A boy needs a father to show him how to be a man, and I didn’t get that. Then watching you go through that birthing process—how incredibly strong you were—and being wrong about Alia. I guess it made me feel like a child. And I wanted my dad. So I went looking for that.”

This was heartfelt; Doug was confused. And the sympathy Mer responded with was real. The notion that he might be bisexual didn’t enter their conversation then. Bisexuality was not yet broadly accepted as a unique orientation. (The initialism LGBTQ+ wouldn’t begin to acquire its B for bisexual until the late 1980s.) In Doug’s mind, the fact that women aroused him was proof that he wasn’t homosexual—only wounded and in need of healing. He would cling to the idea that he could be “fixed” for decades.

In July, a performance artist who lived in a big loft next door, Diana Marto, offered to hold an exhibition of Doug’s and Mer’s work in her space. She had beautiful white walls and was hooked into a different art scene than they were. It would be good exposure, motivation to organize the work they’d each been doing, and a chance to focus on the positive.

The two poured thousands into framing the pieces they’d created in the two years they’d been together—both an affirmation of their love and mutual inspiration, and an investment in their future.

They planned the show for a month later, August 3, 1979.

Mid-July, Dennis Peron got busted—again. He had scarcely begun his four years of probation for the 1977 arrest. But he had gone right back to dealing, opening a new pot shop at a friend’s house on Fell Street. He had also announced that he was running for supervisor of District 5—Harvey’s old district. Dennis felt he owed this to his slain friend.

The Big Top bust had taught Dennis not to do business in his home. Since Dennis didn’t live at the house where the deals were going down this time, and was physically nowhere near the location when the sting happened, the charges wouldn’t stick. The case ultimately got dropped due to weak evidence but not before entangling Dennis in months of legal hassles. “I want to call a truce with the narcotics officers,” he told a San Francisco Chronicle reporter. “But I’m too afraid to walk up to them and say it. They don’t really care for me.” Privately, Dennis suspected that this bust was more about political intimidation over his bid for supervisor than a serious effort to put him behind bars.

Meridy sighed over the news. But one detail made her heart gallop. Police bragged to reporters about confiscating Peron’s address book, which they said contained the names of more than two thousand customers and associates; Mer had no doubt that her name and phone number were among them.

“For the last time, Doug,” she said. “We have got to get rid of those fucking ledgers.”

It was the same fight they’d had a thousand times, but now there was desperation behind it. “This is not a game!” Mer shouted. “They have Dennis’s address book.”

“I’m not discussing this again. Period! That’s it!”

“But you name names, for Chrissake. You like all those Willits people so much? Then don’t rat them out with your asinine ledgers!”

Cheryl was fed up with the fighting. She felt that the frequency and intensity with which Doug berated Mer for her weight amounted to abuse. She thought Mer was a fool for staying with him despite a flock of red flags.

Mer and Doug would start yelling, which would scare the kids, so they’d scream. The warehouse was big but not big enough for that kind of drama. Cheryl took her son and moved in with Barb up the street. Nearby but far enough away not to hear Doug and Meridy yell.

Occasionally, when Mer felt lost in the relationship, she phoned Paula, Doug’s grandmother in Long Island, to ask her advice. Ever since her visit before marrying Doug, Mer had thought of the older psychic as a guiding light. Paula had known Doug his whole life; she understood him well enough to be critical without judging.

“Funny you should call today,” Paula said. “I was watching Lawrence Welk and he had a psychic named Irene Hughes on as his guest. Do you know of her?”

“I may have heard the name . . .”

“She’s famous for predicting Robert Kennedy’s assassination, you know. She also foresaw the exact number of inches that would fall in the Chicago blizzard.”

“That’s right!” Mer said. The same blizzard had hit Madison while she was in college. She did remember Irene Hughes.

“Well, she said something today that troubles me. She feels very strongly that San Francisco is going to suffer a terrible earthquake the likes of which has not been seen in our lifetime. It will put the 1906 quake to shame. And it’s going to happen in January of 1980.”

Mer told Paula about Doug’s earthquake dreams, the apocalyptic visions, her frustrations with him for refusing his medication, the seizures, the fights.

“You know,” Paula said, “my grandson is quite a talented psychic—I can’t imagine where he gets it from!” She giggled. “The trouble is that he picks up too much information and can’t always tell what’s true. One must separate the wheat from the chaff.”

Should they worry about an earthquake, a nuclear meltdown, a bust, or nothing at all?

Irene Hughes, sweet faced and grandmotherly, was making the talk-show rounds with a variety of predictions. She said, for example, that Jimmy Carter would get reelected for a second term on a ticket with a black vice president. And that voices from outer space would shock the world in 1986. Over time, Hughes would produce a mixture of hits and misses—with enough of the former to maintain a following.

For Mer, the what ifs became more insistent. One Wednesday in late July, Mer was resting on the barge in her middle room. She unsnapped the pocket of her leather-bound I Ching and slipped out her three tarnished coins for her usual weekly hexagram. What is our course for this week?

Six. Yang. Yin. Yin. Yang. Six.

This was bad. Opening her book, she fanned the pages to “29. K’an/The Abysmal (Water).” This was never a pleasant hexagram to get, but what really hit her was the changing line she’d rolled, six at the top.

Bound with cords and ropes,

Shut in between thorn-hedged prison walls:

For three years one does not find the way.

Misfortune.

Mer charged out of her room to read the interpretation of that line to Doug. “Listen to this: ‘A man who is in the extremity of danger has lost the right way and is irremediably entangled in his sins has no prospect of escape. He is like a criminal who sits shackled behind thorn-hedged prison walls.’”

“Ew,” Doug said. “That’s not good.”

“That sure sounds like a bust, doesn’t it?”

They sat together at the kitchen table while Mer threw hexagram after hexagram looking for an exit. What is it to operate through the summer and then leave? What do we realize by taking a break and then resuming? Is it in accordance with natural law for Sticky Fingers to continue?

All bad.

Not just a little bad, but the most disturbing imagery the I Ching had to offer. “A hundred thousand times you lose your treasures . . .” “The bed is split to the skin . . .” “You’ve let your magic tortoise go . . .” “Waiting in a pit of blood . . .” “The nose and lips cut off . . . .” “Misfortune from within and without . . .” No matter how Mer phrased her questions, no matter how fervently she hoped for better results, the oracle was clear: dark days were coming.

Then Doug said, “Ask what it is for us to move up to the country.”

“All right.” She closed her eyes, took a deep breath, and muttered her question while throwing the coins six times. The oracle gave her “40. Hsieh/Deliverance.”

Thunder and rain set in:

The image of DELIVERANCE.

Thus the superior man pardons mistakes

And forgives misdeeds

The country.

Willits.

It wasn’t what Mer wanted, but it was a way out. Cheryl, also an I Ching devotee, agreed that the message was unequivocal: it was time to close. Rent for the warehouse, which wasn’t zoned for residential use anyway, was paid month to month in cash; Doug phoned the landlord and gave notice. Mer broke the news to Carmen and the Wrapettes. Nobody was thrilled, but no one wanted to get busted either.

With a decision made, the feeling of impending doom receded. More hexagrams followed. Doug and Mer concluded that they should operate for two more weeks and make as much money as possible. But a third week would bring a rain of misfortune.

A hexagram had started Sticky Fingers Brownies on July 4, 1976, and now a hexagram would end it. If you believed that magic could open doors, you had to accept when it closed them.

On the next brownie run, customers bought in a panic. Folks who usually wanted two dozen put in orders for the weekly maximum of ten dozen to stock their freezers.

“We didn’t know what we were going to do,” says Dan from the Village Deli. “It was such a tragedy! Truly the end of an era.” He and Kissie spent a stoned night asking themselves, Why is this happening?

Doug called his bag that week The Age of Kali. The dark Hindu goddess of transcendence, keeper of the rhythm of time, essence of female sexual power, Kali protected Mother Nature from the evils of mankind. She could be ruthless when disrespected. Though she is often portrayed with skulls around her neck, Doug drew a more visceral version of Kali wearing a belt made from the severed heads of businessmen; blood pours from their necks down her thighs.

On his route through the Haight and Noe Valley, Doug felt full of portent. While telling customers of their closure, he also warned them. “If you’re smart, you’ll get out,” he told people. “And if you don’t get out, get ready.”

He was right.

Not about the massive earthquake. But about untold suffering and loss of life. A new virus was already lurking in the blood and spreading unchecked through the community. Some men would later look back at 1979 and remember a strange fever that came and went without explanation. Kali was indeed coming to San Francisco.

The next week, Doug and Mer drove the three hours to Willits to lease a small two-bedroom farmhouse on a country road near town. Nothing fancy, but the landlord took their cash with no questions. They returned to the warehouse the same night and started packing.

To fill the huge orders, Carmen started baking on Tuesday of the final week and didn’t stop until Saturday afternoon. Throughout, Doug, Mer, and Cheryl debated what to do with the thriving underground network of customers they’d cultivated. A few people had expressed interest in buying the business. Should they cash in? Hexagrams brought lines about greed and overreaching. Giving it to Cheryl or a trusted friend like Stannous looked even worse—like it would bring the law down on all their heads. Each option was weighed and ultimately discarded.

Then, as she and Doug were settling into bed, a favorite axiom floated into Mer’s mind. “You know,” she said, rolling to face Doug. “We always say that if you really want something you should let it go, right? If it’s meant to be yours, it’ll come back.”

“If you love it, set it free,” Doug said.

“So, let’s give it away.”

Doug shook his head. “We looked into giving it to someone and that wasn’t good.”

“I mean to everyone. What if Sticky Fingers isn’t ours to keep? Maybe it belongs to San Francisco. Let’s print the recipe on the bag.”

She and Doug connected in that moment with a zap of the electricity that had brought them together.

“I like the way you’re thinking,” Doug said finally.

“That feels right, doesn’t it?” Mer beamed. “Give it up and you get it all.”

Then they laughed. Laughed and laughed.

On the final bag, above the recipe, Mer wrote, Give it up and you get it all! in ornate script. Lettering across the bottom said, Power to the people! We love you, Sticky Fingers Brownies.

The art show they had been planning at Diana Marto’s doubled as a bon voyage party where, as my mom describes it now, her art “sold like a motherfucker” and his didn’t.

Oh, I can see this so clearly. My mom with her social ease, laughing confidently, proud of her work but acting casual about it. She’d framed dozens of figure drawings and priced them low enough for people to buy without having to sleep on it first. Doug, with his social awkwardness, standing beside his expensive opuses. Not letting the paintings speak for themselves but asking anyone who looked, “So, what do you think this painting is trying to tell you?” then explaining the correct answer. Each piece was priced in the thousands, as if this were a New York gallery opening instead of a San Francisco studio party.

The next morning, Doug would seethe while Mer would silently gloat as she pretended to be humble.

With Sticky Fingers officially closed, Doug consented to burning the ledgers that had been such a point of contention. Mer, giddy with relief, wanted to do it immediately, before he changed his mind. She called Cheryl over, and the three of them went together to Baker Beach to burn the ledgers in an ocean-side firepit.

That night, they said prayers of thanks, prayers of goodbye, prayers of hope for fruitful futures. As waves tumbled roughly onto the shore, the pages curled and caught fire, sending tiny bright sparks into the frigid Pacific wind.

The bakery had begun, only three years before, with breads and muffins that the Rainbow Lady had carried in her basket while saving to visit Findhorn. Now Sticky Fingers was turning out more than ten thousand brownies per month. It had bloomed into the largest known cannabis-food business at that time in California—if not the world, as Laurence Cherniak believed—and the first to offer weed edibles through a high-volume delivery service.

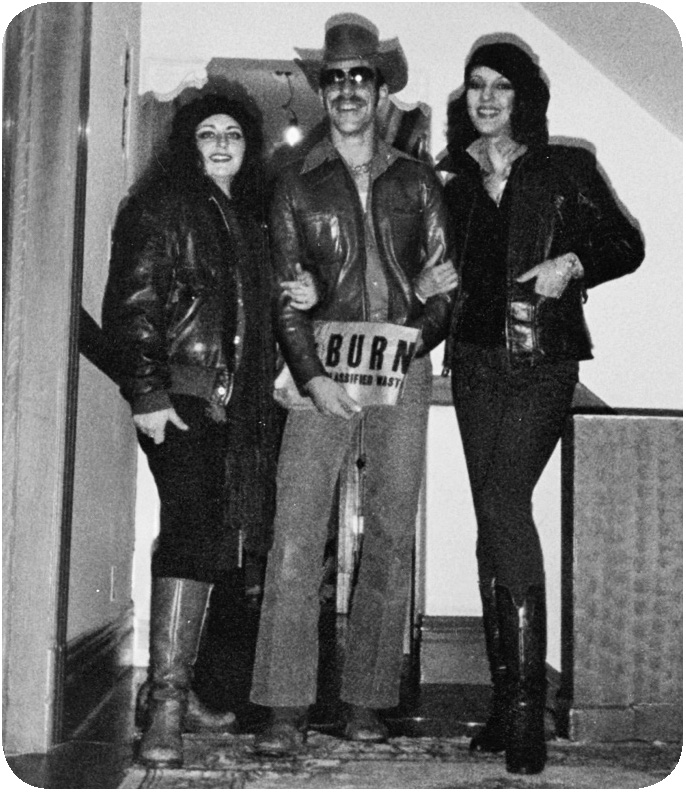

Meridy, Doug, and Cheryl off to burn the ledgers.

Fast-forward four decades, and their industry, now called cannabusiness, is a booming semilegal market that exceeded $10 billion in the United States in 2018. Though projections vary, most predict at least double that value in the next few years. This was all new in the 1970s, and the risks were real. At each turn, Sticky Fingers Brownies grew organically through serendipity and their belief in magic. It was a home-baked revolution.

Monday morning, the phone was ringing like mad.

“Have you seen it? Get a newspaper!”

Herb Caen, the beloved columnist, had written about their decision in his weekly spot in the San Francisco Chronicle.

HEAD SET: “Thank God It’s Friday” had a hollow ring in certain parts of town last Friday, for THAT bakery in the Mission went out of business. THAT bakery made only one product—marijuana brownies, individually wrapped “to insure freshness and quality control”—which brought happiness to hundreds of office-workers each Friday for the past two years . . . In this city of wagging tongues, the secret of the Brownie Ladies and the Mission bakery never got to the law, but the owners decided not to push their pot luck. Fridays will never be the same.

Any other week, this kind of press would have sent the crew into a panic. But Caen nailed the essential detail: they had closed. This would send a message to the vice squad that if they’d hoped to pinch Sticky Fingers they were too late. Bark up a different tree, boys. Good old Herb, Mer thought. He waited until we were safe.

Doug and Mer had just finished reading the article together shortly past ten a.m. and were getting ready to dig into their last big day of packing when the warehouse jolted. The old wood creaked, dishes rattled, a coffee mug tumbled off the counter and shattered. Measuring 5.7 on the Richter scale, it was the largest earthquake in sixty-eight years. Aftershocks rolled throughout the morning. They couldn’t pack fast enough.

My parents took me across the Golden Gate, and we vanished into the countryside.