The scientific man does not aim at an immediate result. He does not expect that his advanced ideas will be readily taken up. His work is like that of the planter—for the future. His duty is to lay the foundation for those who are to come, and point the way.

—Nikola Tesla

TESLA ARRIVED IN NEW YORK IN JUNE 1884 with four cents in his pocket, and the America he encountered seemed rough, crude, and a century behind Europe. The police were curt when he asked for directions. Cab fare was more than four cents, so he started walking. When he encountered a man in front of his shop kicking a machine, Tesla volunteered to fix it and was handsomely rewarded with a twenty-dollar bill.

Nikola Tesla's working life in America was to begin the next day. With his letter of recommendation in hand, he was off to meet the great Thomas A. Edison. Batchelor's introduction read as follows: “I know two great men and you are one them; the other is this young man [Tesla].”

Tesla was thrilled at first to be working for the famous American inventor. But the 28-year-old Tesla and 37-year-old Wizard of Menlo Park were a contrast in styles. Tesla brought with him courtly Old World manners and refined European dress. He was fluent in English, well-read, full of hygienic phobias, and anxious to learn as much as he could about American customs. Edison, by contrast, was often gruff, dressed in plain home-made clothes, and spent the workday in a workman's lab coat. He was a boastful propagandist and would let little stand in his way.

A brilliant inventor and innovator, Edison was an aggressive businessman who built profitable commercial enterprises through guile, cunning, and a focus on profits. He supplied direct-current electricity for lighting some of the most opulent mansions of Lower Manhattan, as well as certain factories, theaters, and public venues around the city. His empire consisted of the Edison Machine Works on Goerck Street downtown and the Edison Electric Light Company on Fifth Avenue. His generating station at 255-57 Pearl Street served the entire Wall Street and East River area. He did his most important research at a laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey, and later West Orange, New Jersey.

Virtually from the moment Tesla stepped into Edison's domain, the company was beset by crises. Fires resulting from faulty electrical wiring threatened the mansions lighted by Edison Electric. The S.S. Oregon, the first ocean liner with electric lighting, was delayed at the docks and losing money by the hour because its dynamos were unable to generate power. Edison, eager to expedite repairs so as not to jeopardize ties with his major financial backer, J. Pierpont Morgan, promptly dispatched his newly arrived assistant to make the necessary repairs. Tesla later recounted:

In the evening I took the necessary instruments with me and went aboard the vessel where I stayed the night. The dynamos were in bad condition, having several short-circuits and breaks, but with the assistance of the crew I succeeded in putting them in good shape. At five o'clock in the morning, when passing along Fifth Avenue on my way to the shop I met Edison with Batchellor . . . returning home to retire. “Here is our Parisian running around at night,” he said. When I told him that I was coming from the Oregon and had repaired both machines, he looked at me in silence and walked away without another word. But when he had gone some distance I heard him remark: “Batchellor, this is a d—n good man,” and from that time on I had full freedom in directing work. (My Inventions)

With a promise of $50,000 for designing improved dynamos, Tesla worked on the project every day, seven days a week, until completing the task. When he went to his boss to report his success and claim his payment, Edison dismissed him with a laugh and curt reply, “You don't understand our American humor.”

Nor did Tesla ever have the chance to present his alternating-current theories or demonstrate his induction motor to Edison. His every request fell on deaf ears. Edison was heavily invested in delivering direct current to his profitable line of arc-lighting systems. Although Tesla would work for Edison for only six months, their strained relationship would have far-reaching repercussions in the 20th century.

With the sting of Edison's rebuke fresh in his ears, Tesla knew he needed to press forward with greater resolve. His time working with Edison enabled him to observe the genius close at hand, but Tesla would challenge his theories and wage a war of words with Edison for years to come. In one newspaper article, he wrote:

His [Thomas Edison's] method was inefficient in the extreme, for an immense ground had to be covered to get anything at all unless blind chance intervened and, at first, I was almost a sorry witness of his doings, knowing that just a little theory and calculation would have saved him 90 per cent of the labor. But he had a veritable contempt for book learning and mathematical knowledge, trusting himself entirely to his inventor's instinct and practical American sense. In view of this, the truly prodigious amount of his actual accomplishments is little short of a miracle.

Bolstered with confidence after his experience with Edison, Tesla set out to organize his own notebooks on advanced arc lighting and the construction of commutators. He reasoned that this would be a valuable first step in advancing his own ideas on alternating current. A scheme took shape.

Tesla was a man of strong opinion and well-formulated ideas. He could visualize the structure of an electrical machine down to the tiniest wire. While working at Edison Machine Works, he also developed a reputation for hard work and innovative problem-solving. That reputation spread beyond the offices of the Edison plant and enabled him to gain access to individuals who might further his plans.

Perhaps it had not occurred to Tesla immediately that he should apply for design patents. In his case, as for other inventors, to patent a process or design does not necessarily require physical creation. One example would be the development of patent leather. This invention was left to Seth Boyden, who in 1888 made hard, shiny leather for the manufacturing of boots in Newark, New Jersey. When asked why he didn't request a patent for patent leather, Boyden said, “I introduced patent leather, but it should be remembered that there was nothing generous or liberal in its introduction, as I served myself first, and when its novelty had ceased and I had other objects in view, it was a natural course to leave it.” Though he did not seek fame or fortune for his invention, Boyden was greatly respected in his own lifetime. He lived out his remaining years in a house in Maplewood (then called Hilton), New Jersey, that had been donated to him by grateful industrialists. In 1926, an admiring Thomas Edison said of Boyden, “He was one of America's greatest inventors.... His many great and practical inventions have been the basis for great industries which give employment to millions of people.” Seth Boyden—not Tesla—was the man Edison named as the second-greatest inventor in American history, after himself.

Soon after he resigned from the Edison organization in 1885, fortune smiled on Tesla. He was approached by two New Jersey residents, Benjamin A. Vail, a lawyer, and Robert Lane, a businessman, who were both excited about the prospects for electric lighting and wanted a piece of the pie. Their plan was to enlist Tesla in a new business enterprise called the Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing Company. They would join a burgeoning field to make and distribute arc-lighting equipment across the country.

Vail and Lane made Tesla a partner and issued him stock in the company. Buoyed by his newfound status and position, Tesla set to work on improving his designs for manufacturing arc-lighting equipment, generators to power the equipment, and regulators to control the amount of electricity flowing to the equipment. His improvements resulted in more efficient methods to deliver light, with less energy loss and reduced overheating.

Now it was the moment for Tesla to protect his ideas by patenting them. He would have something to show for his work beside his physical exertion. According to biographer Marc J. Seifer, Tesla met in March 1885 with the noted patent attorney Lemuel Serrell, a former agent of Edison's, and Serrell's patent artist, named Raphael Netter. Over the next several months, Serrell and Netter filed a series of patents that were assigned to the Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing Company in return for stock shares in the company. The initial set of patents reflected major improvements in the components of the arc-lighting process. PATENT 335,786 – ELECTRIC-ARC LAMP was the first of some 300 patents Tesla filed in his lifetime.

In telling fashion, Tesla clung to his European roots in filing the official document with the United States Government, beginning the application as follows:

To all whom it may concern:

Be it known that I, NIKOLA TESLA, of Smiljan Lika,

border country of Austria-Hungary, have invented . . .

It would not be until 1891, when he became a naturalized U.S. citizen, that Tesla would exclude the name of his homeland from his patent applications.

It was Tesla's hope that once he filed the patents and demonstrated real improvements in the arc-lighting system, he would be able to win the support of Vail and Lane for his AC motor system. But whenever he broached the subject, his two partners strung him along. Like Edison before them, Vail and Lane were entrepreneurs. They already had a system that worked well and, they believed, optimized their profits. Arc lighting was the talk of Rahway, NJ, where their system illuminated the town's streets and factories. Vail and Lane were not the least bit interested in branching out into another untested project.

Once Tesla assigned the patents to Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing Company, the two partners saw no further need to employ their inventor. So they disbanded the company and opened a new one to distribute lighting to the growing city of Rahway. As Tesla recounted it, “In 1886 my system of arc lighting was perfected and adopted for factory and municipal lighting, and I was free, but with no other possession than a beautifully engraved certificate of stock of hypothetical value.”

The later part of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century were wild times for inventors, investors, and individuals with business acumen who sought to protect major technological innovations by filing for patents. Great strides in transportation, the transmission of energy, industrial processes, domestic convenience, and home entertainment were spreading across the United States with a rapid rate. Edison had invented the phonograph in 1877 and, with Louis Howard Latimer, he would invent the first long-lasting incandescent light bulb in 1879. Soon to come were the invention of the airplane by Orville and Wilbur Wright in 1903, the Model T by Henry Ford in 1908, and the large-scale moving assembly line in 1913.

Tesla's AC power system would eventually fit neatly into the excitement of the Industrial Revolution and have as great an impact as any of its other inventions. Tesla's arrival in New York in June 1884 came barely a year after the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, providing road and rail access between Brooklyn and Manhattan. Unlike John and Emily Roebling's “Great Bridge,” however, Tesla's flights of fantasy regarding the production, purchase, transmission, distribution, and sale of electricity for residential, commercial, and industrial purposes too often remained brilliant ideas rather than becoming realities.

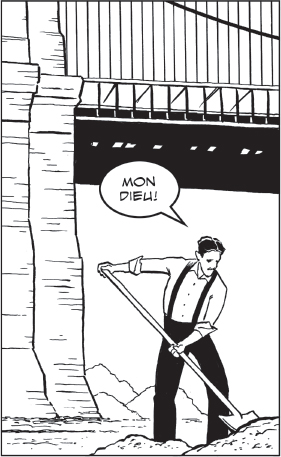

For all his dreaming, Tesla's concept of an AC power system still had not been developed. And after being abandoned by Vail and Lane, the inventor needed a way to support himself. Now, instead of a laboratory, he found himself literally digging ditches in New York City. The Brooklyn Bridge loomed within his sightlines, glowing after sunset with 70 arc lamps operated by another competitor, the United States Illuminating Company.

The Brooklyn Bridge was the longest suspension span ever built to that time, a testament to modern engineering, entrepreneurial ingenuity, and business acumen. These were three lessons that Tesla had not yet fully grasped. While innovations in electrical engineering still reverberated in his mind, the great practical questions were left unanswered.

What would he need to do in order to convince investors that his ideas were viable? Would Tesla's AC system render all the time, energy, and significant investments in developing, manufacturing, and distribution of electricity via the DC system obsolete? Would he be able to prove that his system would generate large profits? Would the system prove safe? Would it require the circus mentality of P.T. Barnum, who took 21 elephants across the bridge in May 1884, to demonstrate the superiority of AC?

In the meantime, he continued to dig ditches. His savoir faire (sophistication, correct behavior, adaptability) and his ability to speak many languages, including French, did him little good with a shovel in his hand. Nor did his lack of business savvy help the situation. Here he was at the age of 30, by which time many men were well-established in their careers. Tesla had come to America with great hope and promise, but success now seemed farther off than ever and he was plagued by material want, utterly depressed. “My high education in various branches of science, mechanics, and literature,” he would later write, “were a mockery.”

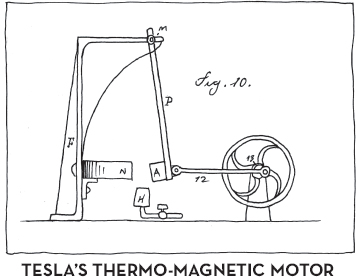

With little to show for his efforts other than dirty hands, worthless stock certificates, and copies of patents assigned to other parties, there still had to be a way for him to climb out of the hole. One possibility might be to file a patent in his own name. As in the case of the arc-lamp application, however, the detailed description and diagram could not be dashed off so easily. The application had to be specific to prevent anyone from infringing on the patent. Filing the paperwork was often a long, arduous process, drawing the inventor into an extended love/hate relationship with the patent office. And there was not even a guarantee that the patent would be granted. How Nikola Tesla had the legal knowledge, skill, and patience to file successfully for PATENT 396,121 – THERMO-MAGNETIC MOTOR, 1886, remains a mystery and a credit to his resourcefulness to the present day.

Although a strong knowledge of electrical engineering is necessary to thoroughly understand many of Tesla's patents, at the heart of this electromagnetism patent is the simple “Right-Hand Rule” of physics as observed by Michael Faraday (1831) in presenting his theory of electromagnetic induction theory. The diagrams below illustrate the Right-Hand Rule.

In the diagram below, imagine a conducting rod placed perpendicular across the index finger with a current flowing through it in the direction of Induced Current I. When a current (in the direction indicated) passes through this rod or the rod in the right picture, a magnetic field radiates out from them. Starting and stopping the flow of current changes the magnetic field—a key principle of Tesla's work on motors.

Tesla knew that magnets lose their magnetic strength when heated. To demonstrate this phenomenon, he describes a small motor in his patent application for the thermo-magnetic motor. The motor consists of a fixed magnet (N), an iron pivoting arm (P) with a moving magnet (A) attached to it, a leaf spring (FM), a Bunsen burner (H), and a flywheel. At normal temperature, the fixed magnet is strong enough to pull the pivot arm and compress the spring. But when the pivot arm is pulled toward the fixed magnet, it passes across the flame of the Bunsen burner. The flame heats the pivot arm and causes it to lose the magnetism induced by the fixed magnet. The force of the compressed spring is now greater than the force of the magnetic field, causing the pivot arm to swing away from the fixed magnet. Because the pivot arm is connected by a crank to the flywheel, the motion of the pivot arm causes the flywheel to turn. As the pivot arm swings out of the flame, it cools off and is attracted once again to the magnet. Now the strength of the magnetic field is greater than the force of the spring, causing the pivot arm to swing back toward the fixed magnet and the flame. In short, Tesla's patent application outlined the basic principle of the motor. Beyond that, it was instrumental in opening the door to his development of the AC motor.

What may have sounded like the ramblings of a mad man digging ditches—talk of lost patents, a lost company, lost inventions, and the genius of his alternating-current system—caught the ear of Tesla's foreman, who introduced him to Alfred S. Brown, a prominent engineer for the Western Union Telegraph Company. Brown himself held a number of patents on arc lamps and was well aware of the limitations of the prevailing DC apparatus. He was immediately impressed with Tesla's ideas and contacted a “distinguished lawyer” from Englewood, New Jersey, named Charles F. Peck.

Brown and Peck were well-versed in business, corporate takeovers, and the lawsuits being filed among the various telegraph companies spreading across the United States. Their experience and practical knowledge in exploiting technological innovation made them ideal partners for Tesla. In Tesla, conversely, Brown and Peck appeared to have found the perfect partner to exploit the new technology.

Peck, however, remained skeptical. He knew that others had failed in creating a viable AC system and did not even want to see a demonstration. In attempting to win his support, Tesla recalled the tale of Christopher Columbus in seeking an audience with the queen of Spain to fund his exploration. In order to do so, he wagered courtiers that he could stand an egg on end. The crowd gathered around and tried in vain. It tried some more and failed. Finally Columbus stepped in, cracked the egg gently on one end, and stood it on the flat surface. He won the bet and secured the necessary funding from Queen Isabella.

Tesla repeated the experiment for Peck, who did not immediately see the connection between Columbus's Egg and Tesla's boasts of creating a thermo-magnetic device, a key element of the AC electrical system. Shrewdly, Tesla challenged Peck to provide funding if he could do better than Columbus and make the egg stand without even cracking the egg. Peck agreed.

Tesla wasted no time over the next few days, enlisting the help of a blacksmith to cast a hard-boiled egg out of copper and brass, and fastening his four-coil magnet to the underside of a wooden table. When he reconvened with Peck and Brown, Tesla placed the copper egg on the top of the table and applied two out-of-phase (or alternating) currents to the magnet. To their astonishment, the egg stood on end. They were even more stupefied when the egg and four brass balls started spinning by themselves on the tabletop. While it looked like magic, Tesla explained, the egg and balls were spinning because of the rotating magnetic field. Peck and Brown were duly impressed by this demonstration and became ardent supporters of Tesla's work on AC motors.

Tesla, for his part, learned two lessons from these demonstrations. First, it is easier to convince someone if they see something with their own eyes. Second, the hardest part is being brave enough to try something new. Showmanship became an integral part of many of Tesla's successes in the future.

Together, Brown and Peck raised the capital and provided the technical expertise to set up Tesla in a laboratory. The facility was located at 89 Liberty Street in Lower Manhattan, next to the grounds on which the World Trade Center would later be built. A partnership with Tesla was formed, and the new company was called the Tesla Electric Company.

Under the requirements of the U.S. Patent Office, a single all-inclusive patent could not cover the entire AC system. The system would have to be broken down into separate groups or components, with individual patents filed for each invention in a particular group. Beginning on April 30, 1887, and over the course of the next year, the Tesla Electric Company engaged in feverish patent filing for an AC dynamo and other devices that comprised Tesla's AC system.

Because his inventions were so new and unique in the burgeoning field of electrical science, they encountered little difficulty in gaining approval. The chart below lists some of the company's key early patents. Repeat titles reflect improvements made in successive filings.

Tesla worked relentlessly, often going without sleep. From memory, he was able to reproduce machines he had conceived more than five years earlier in Europe. He designed and produced complete systems of alternating-current machinery: single-phase, two-phase, and three-phase. For each system, he conceived the dynamo for generating currents, the motor for producing power from them, and the transformers for raising and reducing the voltages, as well as a variety of devices for automatically controlling the machinery—including the mathematical theories for all the components.

Nikola Tesla had finally arrived. His patent work in 1887–1888 marked the beginning of a remarkable 15-year run in the field of invention.

Peck and Brown, for their part, developed an astute business strategy, seeking support and endorsements from eminent electrical engineering professionals. Most notably, George Westinghouse, another daring young electrical pioneer and a practical business man, would open his door to back Tesla financially. Thus began the “The War of the Currents” between Tesla's AC system and Edison's DC system.