If we use fuel to get our power, we are living on our capital and exhausting it rapidly. This method is barbarous and wantonly wasteful and will have to be stopped in the interest of coming generations.... The inevitable conclusion is that water power is by far our most valuable resource. On this humanity must build its hopes for the future. With its full development and a perfect system of wireless transmission of the energy to any distance, man will be able to solve all the problems of material existence. Distance, which is the chief impediment to human progress, will be completely annihilated in thought, word, and action. Humanity will be united, wars will be made impossible, and peace will reign supreme.

—Nikola Tesla

IF HIS LECTURES, EUROPEAN AND CROSS COUNTRY TRAVEL, publications, patent filings, mother's death, nervous breakdown, residential and laboratory relocations, ongoing research, and discoveries in the wireless transmission of energy during the period 1892–1893 were not daunting enough, Tesla was about to enter into a milieu that stretched him even further. It was one thing to concentrate so much of his energy on engineering research and the scientific community. Now he had to face the social elite, the Wall Street financiers, and the countless hangers-on that sought a firsthand audience with him. Often after working all day on a project, he would take dinner at posh Delmonico's restaurant and invite celebrities back to his lab for some startling late-evening demonstration. On one occasion, he brought Mark Twain to tears by relating how the author's works were instrumental in healing Tesla's dire illness as a teenager. The recounting of this incident cemented a lifelong friendship between the two men. Twain relished the opportunity to promote one of Tesla's seemingly risky inventions.

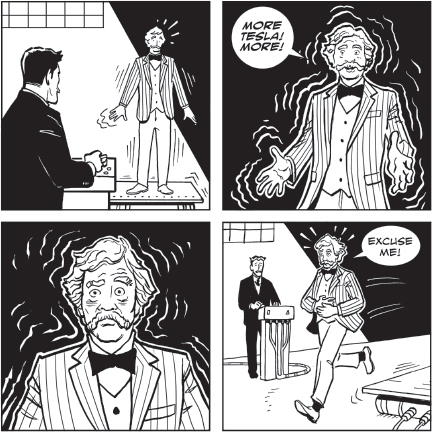

At one evening visit to the lab, according to an oft-repeated story, Twain asked for a demonstration of the benefits of Tesla's work with therapeutic high-frequency oscillators. The famous author ended up furnishing the evening's entertainment when he insisted upon experiencing the gyrations of a platform mounted on an electrified oscillator. Tesla tried to dissuade him, or pretended to, which made Twain all the more determined to prolong the test. Once mounted on the machine, he kept repeating, “More, Tesla more!” Finally, however, he cried out for help, since (as Tesla well knew) one of the effects of such oscillations on the human body was to create turmoil in the bowels.

While working closely with Thomas Commerford Martin on The Inventions, Researches, and Writings of Nikola Tesla, the inventor was introduced to Robert Underwood Johnson and his wife Katharine. As editor of The Century Magazine, arguably the most popular periodical in the United States at the time, Johnson wielded an extraordinary amount of influence. He and Katharine counted among their circle of friends some of America's best-known artists, writers, politicians, and wealthy industrialists.

The Johnsons were intellectually curious, patronized the arts, and enjoyed stimulating conversation. Tesla was a perfect match for their friendship and a frequent guest at their Lexington Avenue soirées. They became lifelong friends and exchanged frequent letters, including some amorous ones from Katharine to Tesla. Not least among their shared interests was the paranormal, a topic of earnest conversation. Katharine Johnson was taken by Tesla's Old World charm but, since she was married, she tried to pass him off to other rich doyennes—to no avail. Tesla was very much married to his work and avoided romantic entanglements.

Evenings with the Johnsons—to whom he affectionately referred as Luka and Madam Filipov, after a favorite Serbian poem titled Luka Filipov—were an opportunity for Tesla to mingle with the social and cultural elite. Among those he met there were authors Rudyard Kipling and Mark Twain; actors Sarah Bernhardt, Eleonora Duse, and Joseph Jefferson; pianist Ignace Paderewski; composer Antonin Dvorak; naturalist John Muir; and architect Stanford White.

Through his associations with Martin and Johnson, Tesla's name appeared frequently in the popular press and his articles gained high exposure. The Inventions, Researches, and Writings of Nikola Tesla received strong reviews both stateside and abroad, and went into a number of editions.

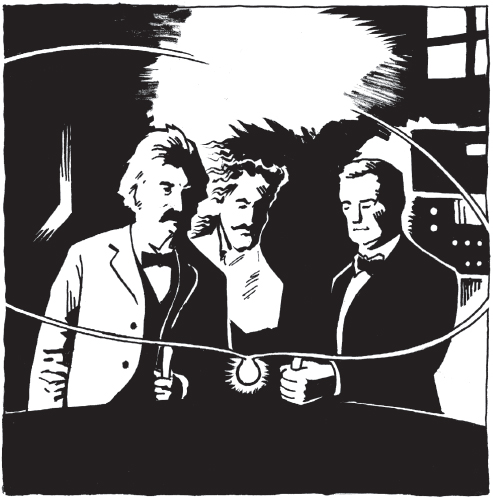

In early 1894, during some of his evening forays at the laboratory with Martin and Johnson, Tesla experimented with early photography by phosphorescent light. He posed for several images himself and others with Twain, Jefferson, and Johnson. Several of the photos made their public debut in Martin's article about Tesla in the April 1895 issue of The Century Magazine. Tesla would go on to write his own article for The Century, titled “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy,” in June 1900.

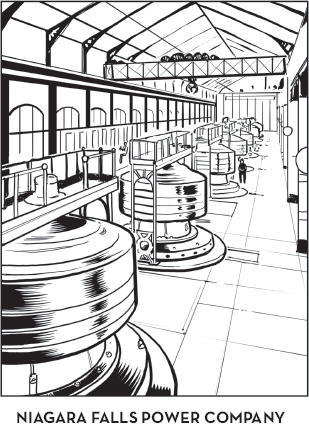

If Tesla was basking in the limelight, Westinghouse was never one to stand still. As early as fall 1890, he had his eye on a Niagara Falls power project instigated by the Cataract Construction Company. At the start, it was proposed as a hydraulic waterwheel power system. The plan was to divert water from the top of the falls through a system of canals and tunnels to power the factories in the village below. The water would drain back into the river through a long tailrace tunnel so as not to mar the landscape near the falls.

Operating in the background over the next two years, Westinghouse monitored the plan's progress. He knew that his success in Telluride and a resounding victory at the Chicago World's Fair could give him a distinct advantage when it came time to bidding on the Niagara Falls contract. In the back of his mind was the feeling that Tesla's AC system would prove more fruitful than any other proposal.

With the tailrace already underway, the original project organizers, led by New York attorney William Birch Rankine, realized that completion would take an enormous amount of capital—more than they had. Rankine approached financier J.P. Morgan for help, but he was lukewarm to the project because it lacked top-notch leadership. Morgan would invest only if Edward Dean Adams, a prominent Wall Street investment banker (and direct descendant of presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams) could be brought in to take control of the finances and engineering. Adams was a major stockholder in the Edison Electric Company and happened to live next door to J.P. Morgan in New York.

Instituted as president of the Cataract Construction Company, Adams was forced to divest his Edison stock in order to avoid a conflict of interest. He then established the International Niagara Commission to attract the best American and European scientific and engineering minds to advise the project. To head the Commission, he secured the services of Britain's Lord Kelvin himself, still a keen proponent of DC. It was a shrewd move on Adams's part to gather these distinguished people and engage them in a contest. Those with the best ideas for harnessing the power of Niagara Falls to transmit energy across great distances would be awarded financial prizes. Among those who balked at the competition was Westinghouse, who commented, “These people are trying to secure $100,000 worth of information by offering prizes, the largest of which is $3,000. When they are ready to do business, we will show them how to do it.”

A number of proposals were submitted, and most were rejected out of hand. When the final bidding opened, there were four that entailed DC power generation and two, from J.P. Morgan's General Electric and from Westinghouse, that would utilize Tesla's polyphase AC system.

Adams and the Niagara Falls Power Company were finally swayed by Tesla's personal appeals and a commitment to transmit power beyond Niagara to Buffalo, and as far as New York City. On May 6, 1893, Adams declared that polyphase alternating current would be their choice for the Niagara project. Six months later, after a series of ugly patent infringement suits between GE and Westinghouse, Adams awarded Westinghouse the contract for building the generators (which Tesla would design) and another contract to GE for building the 22-mile transmission line from Niagara to Buffalo.

In the end, the venture brought investments from some of the wealthiest industrialists in North America in addition to Morgan, such as John Jacob Astor IV, Lord Rothschild, and W.K. Vanderbilt. It was an ambitious and agonizing project, plagued throughout by doubt and financial skittishness. Stanford White was engaged to design what become known as the Edward Dean Adams Power Station to house the great Westinghouse/Tesla generators. From contract to completion, only one person, Nikola Tesla, remained positively convinced that the system would work.

As the Niagara project went forward during the next three years, Tesla continued the exhaustive pace of research at his New York lab, exploring wireless systems to transmit light, power, and communication. William Rankine and Edward Dean Adams were so taken with his ability to keep the Niagara project on course that they offered him $100,000 for a controlling interest in 14 of his patents and the rights to future inventions. Tesla accepted the offer, and the Nikola Tesla Company was founded in February 1895, with Rankin and Adams joining him on the board of directors. The money was much needed, as Tesla had not reaped any funds from the AC system utilized in the Niagara project; he had relinquished all licensing rights to Westinghouse. Fortunately, he still received consultation for his input into the project.

Disaster struck on March 13, 1895, when Tesla's South Fifth Avenue lab was engulfed in fire and the entire building destroyed. His whole world was on the brink of collapse. Equipment, notes, research papers, and years of experiments went up in flames. Although many of his generators and oscillators were housed elsewhere, pioneering work on radio, the wireless transmission of energy, and liquefying oxygen were obliterated. All his thinking would have to be reconstructed from scratch. And he was uninsured to boot.

At first he wandered the streets in despair. An imploring letter from Katharine Johnson, earnest support from Thomas Commerford Martin, and the well-wishes of others eventually lifted Tesla from his despondency. Although he was still bereft of income, financial support from Adams and a burst of self-determination had him searching for a new lab.

Ironically, the first offer of space came from Edison's laboratory in Llewellyn Park, New Jersey, which granted him lab privileges. In late March, he was able to rent space at 46-48 East Houston Street in Lower Manhattan (currently between Lafayette and Mulberry Streets) to house his own lab. Tesla biographer Margaret Cheney would later relate his feelings:

I was so blue and discouraged in those days that I don't believe I could have borne up but for the regular electric treatment which I administered to myself. You see, electricity puts into the tired body just what it most needs – life force, nerve force. It's a great doctor, I can tell you, perhaps the greatest of all doctors.

By July he had the lab up and running and was ready to continue his experiments in the wireless transmission of power and in two new areas, X-rays and radio control. He worked on improving his oscillating transformer to power a new vacuum tube lamp, which he claimed gave out more light and was more efficient than Edison's incandescent lamps. To demonstrate the power of his new bulb, he posed for a famous photo reading James Clerk Maxwell's Scientific Papers while seated in a chair given to him by Edward Dean Adams; in the background is a large spiral coil that Tesla was using in his wireless power experiments.

While invigorated by his new lab and the work he was doing there, Tesla was mentally anguished by the South Fifth Avenue lab fire. He knew he needed a break from his routine and felt that relief might come from a visit to Niagara Falls. After rejecting invitations for years, he finally made his first visit there in July 1896.

With Westinghouse, Rankine, Adams, other members of the Cataract Construction Company, and a throng of reporters, Tesla toured the power system, which was already up and running. The big question at the time was whether the system would be capable of transmitting electricity to Buffalo. Tesla was upbeat and positive, but being around large machinery and noise made him fidgety with anxiety. He was eager to return to his New York laboratory.

At midnight on November 16, 1896, the switch was thrown that delivered the first power to reach Buffalo, some 22 miles away. Tesla was not there to witness the moment of success, which was a dream come true. As a boy 30 years earlier, he had predicted that he would utilize Niagara Falls for the transmission of power.

The success brought Tesla resounding fame but little profit. Practically every major newspaper and magazine in the country lauded Tesla's achievement as one of the most outstanding engineering accomplishments in history. On January 12, 1897, he returned to Niagara and was sumptuously feted at a banquet in his honor by hundreds of dignitaries, luminaries, and investors in the project. Electricity would soon be lighting up homes, factories, and businesses large and small, as well as powering machinery, rail, and subway systems in Chicago and New York.

In due course, Lord Kelvin, who had been a strong proponent of DC for the Niagara project, would concede the advantages of AC for long-distance distribution. “Tesla has contributed more to electrical science than any man up to his time,” he declared.

If the Chicago World's Fair had marked the end of the War of the Currents, the harnessing of Niagara Falls sealed Tesla's victory.

As he accrued more publicity, Tesla's social circle widened even further and with it more women clamored to meet this tall, striking gentleman with the Continental airs, exotic accent, and dapper attire. In today's vernacular, you could say he knew how to work a room, flirt with the ladies, and always spark a conversation. Was it all a mask? Was he playing the bon vivant to attract investors? Women?

By all accounts, Tesla's true comfort zone was the laboratory. His devotion to research and invention stood well above female entanglements. Financial support was most critical to his efforts. While everyone from Westinghouse to the investors in the Niagara project were basking in their success and calculating the wealth they would accrue from their investment, Tesla was, as ever, struggling to finance his next great idea. He was at a crossroads. How could he find backers to develop a wireless transmission system when some of the richest men in America had just poured money into a wired transmission system?

Notwithstanding the consultations on the Niagara Falls project and the disastrous fire at his lab, Tesla had been following the path of his dreams. Much of this was driven by his belief that he could derive energy from the Earth itself. During the intervening years he would do pioneering investigative work on X-rays, earthquakes, Martians, radio, robots, and the wireless transmission of energy.

In 1894, Tesla took some long exposure pictures of Mark Twain with the aid of various phosphorescent tubes. Unfortunately Tesla's research in this area was destroyed by the laboratory fire in 1895. That December, when German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen announced his discovery of X-rays, Tesla remembered that he had salvaged one failed photo from the Twain session. Rather than a picture of the famous author, the image on the glass photographic plate included shadows of the circular lens and the screws on the front of the wooden camera. This image had been captured before the lens cap had been removed for exposure to light.

Upset by Röntgen's announcement, Tesla destroyed the evidence of his work. Gentleman that he was, he granted Röntgen full credit for the invention of the X-ray even though he clearly had produced an earlier example of the process.

Tesla communicated with Röntgen over the course of the next year regarding ways to improve X-rays. He went so far as to self-administer X-rays to his various body parts for potential healing properties, calling the images “shadowgraphs.” Although he noticed burns on his skin and abandoned the practice, he maintained that the repeated application of X-rays would have no long-term effects. The damaging effects of radiation were still unknown at the time. As a number of powerful electrical companies began vying for Röntgen's attention, Tesla abandoned his efforts to improve the X-ray process.

When Tesla sent Mark Twain scurrying for bathroom relief by submitting him to the gyrations of high-frequency oscillators, he had set the stage for future explorations in the transmission of wireless energy. In the years that followed, Tesla returned continually to investigating the phenomenon produced by mechanical oscillators.

In 1898, he reasoned that he could tune his electronic circuits in such a way that the electricity would vibrate in resonance with its circuits—much the way strings vibrate on a musical instrument. Similarly, Tesla visualized mechanical vibrations building up resonance conditions to produce effects of tremendous magnitude on physical objects.

To test his theory, he attached a small mechanical oscillator to an iron pillar on the upper floor of his Houston Street laboratory. As the oscillations were increased, he noticed that certain objects around the room began to vibrate as they came into the same resonance. Tesla described the phenomenon as a “minor earthquake.” In fact, the oscillator attached to the iron pillar sent increasing vibrations down through building, into the ground below, and radiating out in different directions with ever-greater force. This was indeed similar to an earthquake, in which the epicenter is calm but the outer reaches experience greater force and destruction.

Unbeknownst to Tesla at the moment of his test, at Police Headquarters on nearby Mulberry Street, chairs began to move of their own accord, objects slid off desks, plaster fell from the ceiling, water pipes burst, and windows shattered. Fearing an earthquake, but used to strange goings-on in the neighborhood, the police dashed to Tesla's lab. Upon their arrival, the courtly inventor was quoted as saying,

“Gentlemen, I am sorry, but you are just a trifle too late to witness my experiment. I found it necessary to stop it suddenly and unexpectedly and in an unusual way just as you entered. If you will come around this evening I will have another oscillator attached to this platform and each of you can stand on it. Now you must leave, for I have many things to do. Good day, gentlemen.”

For Tesla, the earth-shaking oscillator test provided a window into his new science of telegeodynamics. By utilizing certain vibrations, he theorized, he could literally split the Earth in half. With the correct oscillation, not only could he deal with the transmission of powerful impulses through the Earth to produce effects of large magnitude and distant points, but he could also to detect ore deposits far below the Earth's surface, enemy ships or submarines, or even objects on Mars. Along similar lines, seismologists today are experimenting with time-reversed oscillations to deter potential earthquakes.

The possibility of life on Mars held many Americans in its grip in the mid-1890s. Among those intrigued by the idea—and eager to find out—was Colonel John Jacob Astor IV, one of the richest men in the world, as well as an investor in the Niagara Company. It was propitious that Tesla shared in this fascination. Astor had presented Tesla a copy of his science-fiction novel, A Journey in Other Worlds(1893), which the inventor had enjoyed. Astor himself found time to invent various devices, such as a bicycle brake and an improved turbine engine. Tesla's remarks on signaling Mars might have seemed outlandish to the press, but they forged a bond with Astor that would serve Tesla in the years ahead. “If there are intelligent inhabitants of Mars or any other planet,” he declared, “it seems to me that we can do something to attract their attention.... I have had this scheme under consideration for five or six years.” Tesla's reasoning, it will be noted, follows the line of his experiments in mechanical oscillation. As Tesla was quoted in The Electrical World (April 4, 1896), sending or receiving signals from Mars

... is the extreme application of this principle of the propagation of electric waves. The same principle may he employed with good effect for the transmission of news to all parts of the earth.... Every city on the globe could be on an immense ticker circuit, and a message sent from New York would be in England, Africa and Australia in an instant. What a grand thing it would be in times of war, epidemic, or panic in the money market!

Before the fire at South Fifth Avenue, Tesla would set up an oscillating transmitter in the lab and walk around New York with a receiver to see if it would detect signals. Sometimes he received intermittent signals as far north as the Gerlach Hotel on West 27th Street. After the lab was destroyed, while casting about for money and projects, he used some of his credit lines from Westinghouse and Adams to outfit the Houston Street lab and continue wireless research.

Already in his 1893 lecture at the annual meeting of the National Electric Light Association in St. Louis, Tesla had laid out the essential components of a radio system: a transmitter and receiver, antenna, ground connection, and tuning device. That lecture was to be a prelude to more elaborate testing of wireless transmission. The one basic component he had omitted in St. Louis was a speaker, something Tesla would invent and incorporate later. (Among the many physicists of the last quarter of the 19th century who worked on high-frequency electromagnetic vibrations in an effort to invent wireless communication were Germany's Heinrich Rudolf Hertz; England's Sir Oliver Lodge, James Clerk Maxwell, and Sir William Crookes; and the young Italian, Guglielmo Marconi.)

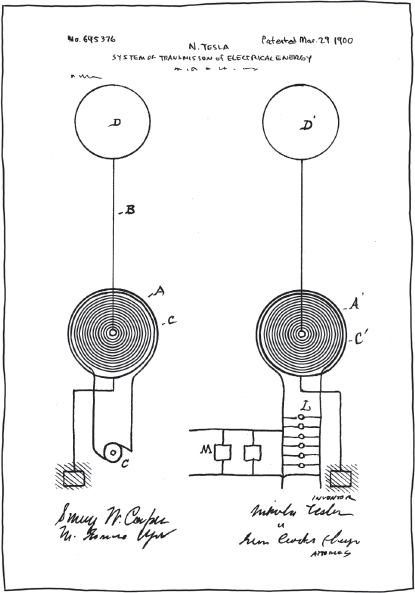

In New York around 1897, Tesla would take secret boat trips up the Hudson River with a battery-operated receiver in hand. At distances of over 25 miles, he found, he was able to receive a musical note in tune with the oscillations generated from his Houston Street lab. Ecstatic at the discovery, he drew up his findings and on September 2, 1897, filed for the Patents 649,621 – TRANSMISSION-OF-ENERGY, issued March 15, 1900, and 645,576 – SYSTEM OF TRANSMISSION-OF-ELECTRICAL ENERGY, issued March 20, 1900.

In the application for wireless transmission (649,621), Tesla discusses the need to transmit and receive signals over high altitudes and across unobstructed distances, so that the terminals between transmitter and receiver are “of large surface, formed or maintained by such means as a balloon at an elevation suitable for the purposes of transmission. The practice of tethering balloons to an extreme height might prove impractical.” Therefore, he goes on to say,

if there be high mountains in the vicinity the terminals should be at a greater height, and generally they should always be at an altitude much greater than that of the highest objects near them. Since by the means described practically any potential that is desired may be produced, the currents through the air strata may be very small, thus reducing the loss in the air.

It would take another few years for Tesla to lure John Jacob Astor to front him the money to test out these theories in Colorado Springs.

Guglielmo Marconi's first U.S. patent application for a radio, Number 763,772, was filed on November 10, 1900—months after Tesla's. The “Radio Wars” were on! During the next half-century, Marconi would be the major challenger to Tesla in gaining credit for the invention of the radio.

As always, Tesla was in dire need of money and finally acknowledged that he needed to make a big splash to attract funding. Concurrent with his experiments in wireless radio, he was working on remote-controlled boats. The moment could not have been more perfect to exploit this project. The USS Maine, a battleship deployed to protect Cuba and U.S. interests on the island from Spain, mysteriously exploded in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898. Implicating Spain in the explosion, the United States officially declared war on April 28, 1898. Tesla rushed to file Patent 613,809 – METHOD OF AND APPARATUS FOR CONTROLLING MECHANISM OF MOVING VEHICLE OR VEHICLES on July 1, 1898, stating in his application,

I have invented certain new and useful improvements in methods of and apparatus for controlling from a distance the operation of the propelling-engines, the steering apparatus, and other mechanism carried by moving bodies or floating vessels.

This was his first foray into a field that he would come to call “teleautomation.” So novel was the application that the patent office sent an examiner to inspect the boat in action in Tesla's lab. The patent was granted on November 8, 1898.

With patent protection, Tesla was once again ready to amaze the public and lure investors. On December 8, 1898, in an exhibition at New York's Madison Square Garden, he demonstrated his teleautomaton, or radio-controlled boat, to the public. The crowd responded with disbelief. To some witnesses, the boat moved by magic, to others by telepathy. A few suspected a trained monkey was installed in the boat, obeying Tesla's commands. In reality, he used a transmitter box to send signals that shifted electrical contacts in the boat, adjusting the rudder, motor, and lighting.

The demonstration could not have come at a better time, as the Spanish-American War was at its height. Tesla saw an opportunity to sell a radio-controlled torpedo to the U.S. Navy, but the idea was met with derision. Perhaps his mistake was trying to sell the weapon as a means of peace rather than war. He reasoned as follows:

These automata, controlled within the range of vision of the operator, were the first and rather crude steps in the evolution of the Art of Telautomatics.... The next logical improvement was its application to automatic mechanisms beyond the limits of vision and at great distance from the center of control.

Tesla felt strongly that wars could be waged machine against machine. And that would be progress, he believed, because with automatons there would be no bloodshed. Tesla remained convinced that his idea for remote control would eventually catch on. Unfortunately, he would not live to see the day when his prophecy would become a reality.

It was around this time that Tesla moved into Astor's recently completed Waldorf Astoria Hotel on Fifth Avenue. It was the epitome of opulence and luxury. Astor treated his friend with the highest esteem, according him such special amenities as his own dining table. But Tesla was broke and living off borrowed money. His research was at a standstill. His New York lab was too small and unsafe for the scale of his projects, and the electricity being generated at the time for the lighting, telegraph, telephone, and transportation systems mushrooming across Manhattan interfered with the wireless transmission experiments he wished to conduct.

Astor, who had been following Tesla's work closely, learned that he required funds to continue his research and invested $100,000 in the Tesla Electric Company. Of this amount, $30,000 went to Tesla directly; the rest went to stock purchases. The injection of money enabled Tesla to take advantage of an offer by Leonard E. Curtis of the Colorado Springs Electric Company to build a temporary plant in that city. This would give Tesla an opportunity to conduct experiments on a gigantic scale. He would be provided with all the land and electrical power he needed for his work. And so, in May 1899, Tesla moved to Colorado Springs.