His life should have gone on, long and productive, but it’s as if someone had pronounced the sentence so often heard by Chekhov: “The work must be finished by such and such a date. . . .” On the page, someone is already tracing the word: end.

—némirovsky, La Vie de Tchekhov

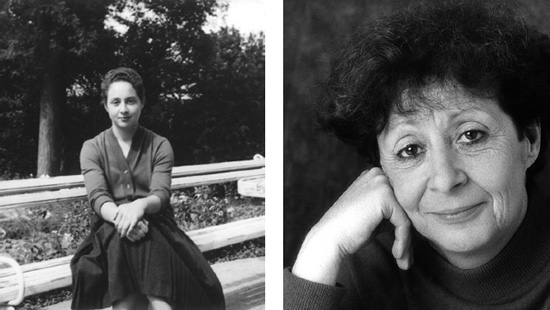

PEOPLE WHO KNOW NÉMIROVSKY’S story often ask, Why did she and Michel not try to hide or leave France or at least leave the zone occupied by the Germans in June 1940? Why did they register as Jews in October, when the first statutes relating to members of the “Jewish race” made it clear that the Vichy government was no friend of the Jews, especially foreign ones? And why did they continue scrupulously observing the law, even when the law itself had become unlawful? Could they have saved themselves if they had made better choices? As we have seen, the adolescent Elisabeth blamed her mother for “being so oblivious politically. She hadn’t saved herself, even though she had every possibility to do so, and she had put us, my sister and me, in danger.”1 But did she in fact have “every possibility” to save herself? Was she really blind to what was happening around her?

These questions seem inevitable, but here more than ever we must resist the temptation to judge by hindsight. While Némirovsky was responsible for her choices, she was not responsible for the fate that befell her. That responsibility lies with the iniquity of the Vichy regime and of the German occupiers of France. Recent historical studies, together with a huge number of personal testimonies published over the past several decades, have shown that survival was unpredictable, often a matter of sheer luck, and that Jews who survived did so in many ways. There was no right way to decide on what to do, since similar decisions could produce strikingly different results. Many Jews who lived in Paris were deported, but many were not; many who fled to the Unoccupied Zone survived, but many did not. The only sure way to escape deportation was to leave the country, but leaving the country was extremely difficult, especially for those who had no valid passports, and even those with documents were often stymied. Walter Benjamin, detained at the Spanish border with a group of refugees and despairing of ever being able to reach Palestine even though he had valid entry documents, took his own life in September 1940; not long after that, all those who had been with him were allowed to cross over.2

On the whole, Jews in France fared much better than those in other occupied countries. Whereas 75 percent of Jews in Holland and 60 percent in Belgium were deported or murdered, “only” 25 percent of Jews in France, roughly 80,000 people, suffered that fate.3 Being a foreign Jew, however, made one’s chances much worse: of the approximately 130,000 people in France who were classified in that category in 1940, 56,500 had been deported by the time the last transport left for Auschwitz in August 1944, a proportion of more than 2 out of 5. Jews who possessed French citizenship, whether of established or of recent vintage, fared better, as long as their citizenship had not been revoked in one of Vichy’s denaturalization projects. Out of an estimated total of 200,000 in 1940, 25,500 were deported, a proportion of 1 out of 8. In other words, if you were a foreign Jew your chances of being deported were almost four times as high as those of a Jew classified as French. Pierre Laval, who was prime minister during the worst period of persecution, between 1942 and 1944, derived some pride from the fact that Vichy targeted foreign Jews before French ones, as if that did him honor—but then, Laval also insisted on arresting and deporting children, since they should not be separated from their parents.4

When war was declared on September 3, 1939, most French families were just returning from their vacations. Irène and Michel had spent the summer with their children, as usual, in the southwestern seaside town of Hendaye, near the Spanish border. In a short story published a few weeks later, one of several she wrote on this theme, Némirovsky describes the general state of shock and disarray that followed. The opening paragraph offers several clues to her own state of mind at that moment: “It was the first night of the war. In wars and revolutions, nothing is more dumbfounding than those first moments when you are thrown from one life into another, breathless, the way one might fall fully clothed from a high bridge into a deep river, without understanding what is happening to you, your heart still harboring an absurd hope.”5 Feeling as if one had fallen off a bridge and was drowning yet retaining an “absurd hope”: these were familiar emotions to Némirovsky, as her brief allusion to revolution makes clear. By a striking coincidence Benjamin, in a letter to his friend Theodor Adorno, used a similar image a few months later to describe the situation of refugees seeking to flee France: “I have seen a number of lives not just sink from bourgeois existence, but plunge headlong from it almost overnight.”6 Némirovsky had no doubt experienced similar feelings during the flight from Russia as an adolescent. Psychologists have noted that one trauma often awakes memories of another, and terror of more to come. With an intuition that can strike one as premonitory, she sets this story, titled “La nuit en wagon” (The night in the wagon), in a crowded train compartment. In our days the train has become an emblem for the persecution of Jews during the Holocaust, owing in part to the brilliant use that Claude Lanzmann made of trains in his celebrated film Shoah (1985). But trains are excellent symbols for the collective experience of civilians during the Second World War in general given that so many people were displaced for various reasons during that time. The train in Némirovsky’s story is heading from the southwest to Paris, and the narrator, an unidentified woman who could be a stand-in for the author, engages in conversation with a young woman who is going to meet her fiancé to spend a last day with him before he joins his regiment. Other people tell their stories as well, establishing an unusual degree of solidarity among strangers. But as the train pulls in to the Gare d’Austerlitz in Paris the solidarity evaporates and everyone is alone: “Suddenly, people seemed not to know one another. . . . The travelers had gone their separate ways without a word.”7 The narrator does not tell us anything about her own situation but acts as a clear-eyed observer of others. Readers of Suite Française will recognize here the stance of the anonymous narrator in that novel, who weaves together the various stories of people heading south in panic nine months later as the German troops overrun the country.

Disconcertingly, the first months of the war were uneventful in France, so much so that the French call them the drôle de guerre, the phony (or even funny) war. The men were at the front but in fact there was no front, only a line drawn at the eastern border, the Maginot Line, heavily guarded, where the expected German invasion never came. Sartre, drafted into the army and stationed in a village in Alsace, had enough leisure time to fill hundreds of pages of notebooks between September 1939 and March 1940, in which he mixed daily observations of life in the barracks with weighty considerations about authenticity and ethics. They would lead a couple of years later to his massive existentialist opus Being and Nothingness.8 At the same time, in Paris, his lover and soulmate, Simone de Beauvoir, kept her own diary, in which she described her days spent writing in cafés in Montparnasse. She was working on her first novel, L’Invitée (She Came to Stay), which would be published in 1943, the same year as Being and Nothingness.9

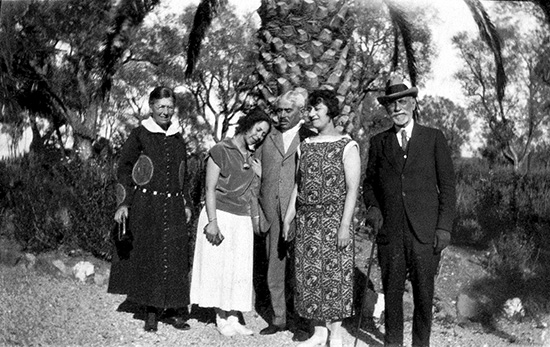

In short, even though the world was transformed, life went on almost as before. Némirovsky published eight new short stories between October and May, most of them in Gringoire and a few in the women’s weekly Marie-Claire, which evidently also paid well. Her novel The Dogs and the Wolves, which she had completed earlier that year, started appearing in serial form in the weekly Candide—known for its nationalist and anticommunist views, though not as much for antisemitism as Gringoire—in October 1939; it was published in book form in late April 1940. Still, Irène and Michel had been sufficiently alarmed at the outbreak of the war to send the children away from Paris. In Le Mirador Elisabeth Gille reports in her mother’s voice that while they were still in Hendaye, on September 3, Irène called the girls’ nanny, Cécile Michaud, and asked her to come and take them to Issy-l’Évêque, her native village, located in a corner of Burgundy near the foothills of the Morvan.10 The girls spent the next eight months in the home of Michaud’s mother and evidently enjoyed their initiation into country life. Denise recalled many years later that despite the hardships of an underheated house and outdoor latrines she felt happy and well cared for and had a wonderful time playing with the kids of a local shopkeeper.11 Elisabeth, who was only two and a half years old, must have felt more disoriented, suddenly finding herself without her parents. Irène and Michel made regular visits from Paris.

Némirovsky’s journals contain no indication of why she sent the children away at a time when no obvious danger threatened them. However, other children were also evacuated from the capital as soon as war broke out, and some families decided to stay in their summer homes instead of returning to Paris.12 Possibly, anticipating the worst, Irène and Michel wanted to prepare a place where they could go if they too had to leave at a later time. Indeed, by the time the German army surged into France from Belgium, in the middle of May 1940, Irène was living with the girls in Issy, having left Paris at the beginning of the month. They were joined in early June by Michel, who had been ill. The bank where he worked, the Banque des Pays du Nord, seems to have seized the opportunity to fire him, and none of his attempts to be rehired had any effect.13 Irène had thus become, now and for the foreseeable future, the family’s sole breadwinner. On June 6 she wrote in her journal, “I realize it would be necessary to write one or two stories, while one can still—maybe—find a place to publish them. But . . . uncertainty, worry, anxiety all over: the war, Michel, the little one, the little ones, money, the future. The novel, the momentum of the novel cut short.”14 The novel in question was Les Biens de ce monde, which she did manage to continue that summer and which started appearing in serial form in Gringoire the following April. By then, it had to be published under a pseudonym, as the Vichy government had barred Jews from the press.

In Némirovsky’s mind her writing and her immediate material problems, including her responsibility for her family’s livelihood, were inseparable: she had to write to live. More than most writers of her class and social position, she relied exclusively on her publishing income and she had no backups, no country house to retire to, no inheritance. Despite her professional success and acquaintances there were very few people she could count on for support, moral and practical if not material. The ones she felt closest to, Michel’s brothers and sister, who had remained in Paris, were as much in need of help as she was.

After that, things moved very quickly. On June 10, as the German army was approaching Paris, the French government and National Assembly headed south, in their own version of the exode. Many deputies were opposed to negotiating an armistice with the Germans, preferring to fight on or at least to form a government in exile, as had been done by Belgium and the Netherlands. But others, most of them conservatives who had opposed the leftward move of the Third Republic in the years immediately preceding the war, argued for an armistice, and they prevailed. On June 16 Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned, clearing the way for Marshal Philippe Pétain, whom he had appointed as a minister a few weeks earlier, to form a new government. Thus Pétain, the revered hero of the First World War, became, at the age of eighty-three, the prime minister of France, or, as he stated in his famous radio broadcast of June 17, he “bestowed on France the gift of [his] person.” Five days later he signed an armistice with Germany, according to which France was divided into an Occupied Zone in the north and an Unoccupied Zone in the south, except for the coastal southern area, including Bordeaux, which was occupied. A demarcation line, which would soon be heavily guarded, separated the two zones. Issy-l’Évêque, where the Epsteins were living, was less than fifty miles north of the line. The Epsteins were thus in occupied territory, under the control of both French and German authorities and police. After November 11, 1942, when the Germans occupied all of France, the strict division no longer held, but some differences still existed between what were now called the northern and southern zones.15

Pétain bestowed more than his person on France. He also bestowed on it a National Revolution that turned the country from a parliamentary democracy into an authoritarian state. Beneath the mask of the kindly old war hero with clear blue eyes, who established his offices in a resort hotel, the Hôtel du Parc, in the spa town of Vichy, was an archconservative leader who blamed France’s humiliating defeat on the moral and political decadence of the Third Republic, dominated by leftists, Jews, and Freemasons. “I hate the lies that did you so much harm,” he thundered in a radio broadcast on June 25, 1940. By an ironic twist this famous sentence was written for Pétain by none other than Emmanuel Berl, who realized a few weeks later that Vichy was not a welcoming place for Jews and who, in spite of his privileged status, spent the rest of the war making himself inconspicuous. He lived from then on in a couple of small villages in the south and even went into hiding for several months in 1944.16

Pétain sought to create a “regenerated” France that would take its place alongside Germany in the new European order. Most French men and women were willing to support him, at least in the early weeks and months before the full extent of his National Revolution had made itself felt. On July 10, 1940, by an overwhelming vote of 569 to 80, including many Socialist and center-left deputies, the National Assembly voted him full powers to revise the constitution, which enabled his regime to claim full legality. But what followed can be compared to a coup d’état. Pétain’s first step was to suspend Parliament indefinitely, thus de facto abolishing the Republic, and to appoint himself as head of state, answerable to no one and governing by decree. While some commentators who later sought to whitewash him claimed he was senile and manipulated by the conservatives who surrounded him, contemporary historians—starting with Robert Paxton, whose 1972 study on Vichy France inaugurated a whole new historiography of the Occupation years—have documented that this claim was false. Pétain knew what he was doing, and the men around him were following him as well as coming up with new ideas. An exhibition at the National Archives in Paris in the fall of 2014 documented in great detail the ideology as well as the activities of Pétain’s government, including Pétain himself, in the persecution of Jews. Among the most damning documents was the typewritten draft of an anti-Jewish decree from 1940 that Pétain had annotated by hand, adding provisions that made the decree even harsher.17

Among the new ideas in the summer of 1940 were a series of decrees whose cumulative intent was to rid France of “undesirable” foreigners generally and to exclude Jews in particular from participation in public life. On July 22 Pétain’s justice minister set up a commission to reexamine all naturalizations that had been issued since 1927, an act which ended up stripping 15,154 people of citizenship, among them 6,307 Jews.18 In August and September new laws restricted membership in the medical and legal professions to those born of a French father, thus eliminating first-generation immigrants. Although Jews were not mentioned in these decrees, they were clearly targeted.19 And they were most definitely mentioned and targeted in the decree of October 3, 1940. Known as the Statut des Juifs, this decree stripped Jews in France, regardless of whether they were native or foreign, living above or below the demarcation line, of basic civil rights. (This was the document annotated by Pétain that appeared in the exhibit of 2014.) The full text of the Statut des Juifs is available on several websites, and reading it today is a chilling experience. Article 1 defines who is a Jew: “Any person descended from three grandparents of the Jewish race, or two grandparents of that race if his or her spouse is also Jewish.”20 The matter-of-fact use of “race” to designate Jews did away with considerations of religion: converts who had three Jewish grandparents were Jews, whether they liked it or not. This article, like the rest of the statute, contravened every principle of the long French tradition of republicanism, according to which all citizens are equal before the law. Jews were henceforth forbidden to hold positions in the government, ministries, the police, the armed forces, the magistrature, including judges at all levels, and the teaching corps, from elementary school through university. And they could no longer work in publishing, journalism, radio, film, or theater, these being “professions that influence public opinion.”21

The day after publishing the Statut des Juifs, on October 4, Vichy issued another decree, this time focusing on “foreigners of the Jewish race.” Such foreigners, the decree stated, could be interned in “special camps by decision of the Prefect of their département of residence” or else assigned to forced residence by the prefect. Each of France’s ninety départements had a prefect appointed by the central government, and the Vichy regime instituted additional regional prefects, who were in charge of more than one département. Thus the Saône-et-Loire, where Issy-l’Évêque is situated, not only had a prefect and a subprefect but also fell under the jurisdiction, with several neighboring départements, of the regional prefect in Dijon. In the Occupied Zone, prefects reported both to Vichy and to the Germans, who regularly asked for reports on Jewish residents. A number of départements, among them the Saône-et-Loire, were cut in two by the demarcation line and therefore had an even more complicated administrative structure. The prefect of Saône-et-Loire, whose office was in the city of Mâcon in the Unoccupied Zone, reported to Vichy, but the subprefect, stationed in the next largest city, Autun, which was in the Occupied Zone, “fulfilled the role of Prefect,” as was stated on all his correspondence, in relation to the “Authorities of Occupation.” Thus the subprefect in occupied Autun sent reports to the German Sicherheitspolizei in occupied Chalon-sur-Saône, to the prefect in unoccupied Mâcon, and to the regional prefect in occupied Dijon, among others. Many of these reports survive in regional archives, some more carefully preserved than others. The Saône-et-Loire archives, located in Mâcon, are unfortunately among the less complete ones, but they still contain some revealing information. Among these is a report dated October 21, 1942, submitted by the subprefect in Autun to the Sicherheitspolizei at Chalon, listing Jews currently living in the area as well as those arrested since January 1942. The entire Epstein family figures on these lists: Michel and Irène appear among those arrested, and Denise and Elisabeth among those still living there. Presumably, their turn could come later.22

Several more Vichy decrees followed the Statut des Juifs, in 1941 and 1942, each one adding more restrictions. Historians have stressed that these decrees were not forced on Vichy by the Germans, as many people thought at the time and as some asserted for years afterward. They were the brainchild of Pétain’s entourage, and Pétain himself oversaw them and signed them.23 The Germans, however, were busy issuing ordinances as well. On September 27, 1940, a few days before Vichy issued its Statut des Juifs, the Germans decreed that all Jews living in the Occupied Zone must register at their local police station or at the sous-préfecture of their department. The penalties for failing to do so would be, the German ordinance assured, harsh. Since the registrations didn’t start until October, after the Statut des Juifs had been published, and since they were handled by French police, public memory associates the order to register with Vichy. In fact, French and German authorities worked in tandem to ensure that the identity cards of Jews in the Occupied Zone would henceforth bear the word Juif or Juive stamped on them.24 Less than a year later, on June 2, 1941, Vichy extended the registration to Jews in the Unoccupied Zone, with similarly harsh penalties for noncompliance. In May 1942 the Germans issued yet another ordinance: starting in June, all Jews residing in the Occupied Zone were to wear a yellow star sewn on their clothing. They could pick up their stars at their local police station or sous-préfecture, with the usual sanctions if they failed to do so. In this, at least, Vichy did not follow the Germans’ lead, and Jews in the Unoccupied Zone never wore the yellow star. But in both zones every Jew who registered became part of a huge surveillance system. In the Paris area individual Jews became part of a card file, or fichier, each person’s fiche listing his or her name, address, profession, and place and date of birth. A person could have several fiches, coordinated with each other. Many people’s itineraries, including those of Michel Epstein’s brothers and sister, can now be followed right through from their first registration to their arrest and internment in the transit camp at Drancy near Paris to the date of their deportation from France. In the provinces things were often less well organized, and instead of card files the bureaucracy kept lists. The main thing was that the system as a whole was extremely efficient, allowing for roundups of Jews in both Paris and elsewhere. In this regard the French bureaucracy could compete in efficiency with the German.

France, June 1940–November 1942, with detail of the department of Saône-et-Loire showing demarcation line.

One can imagine the dismay, disbelief, outrage, and panic the decrees provoked among the Jews of France. While the feelings were shared by all, the actions that accompanied them varied, and the outcomes varied too. Historians as well as survivors have recounted hundreds of individual stories, each of them compelling, but as far as chances for survival went, only vague generalizations can be drawn from them. It was better to have money, better to have good friends who were willing to help, better to be a French citizen, better to be in the Unoccupied Zone, and, best of all, to be in Switzerland or England or the United States if one could get there. Time was of the essence, for what was possible in June 1940 was no longer so in October and even less so the following year. Being inventive, seizing opportunities, daring to break the law if necessary—“se débrouiller” is the French term for it—were essential, but even that was no guarantee. Not all who could hide or escape tried to do so, some who tried, failed, while others who did nothing nevertheless survived—and so on, in a fascinating yet familiar litany. Much of the most interesting current work by historians of the Occupation years focuses on individual stories in all their variety or on in-depth studies of Jews in a single town or community. For example, Nicolas Mariot and Claire Zalc have studied in detail the Jewish responses to persecution in the northern mining town of Lens, basing their research on individual documents and official correspondence as well as on statistical data. Their work confirms that while generalizations are possible, individual stories often prove them wrong.25

One thing is certain: the overwhelming majority of Jews in France, both native and foreign, followed the orders to register. And once they had done so, as the historian Jacques Semelin notes, they became official victims of laws whose “purpose was to make them into pariahs.”26 Historians have speculated on the reasons for this massive obedience and generally agree on at least three: among foreigners, fear of being on the wrong side of the law was an ingrained habit, so registering was just one more bureaucratic rule they followed; among the French Israélites, their long-standing respect for legality and their confidence in the Republic, even if accompanied by indignation and defiance, led to similar results; finally, some in both groups felt a moral obligation to declare their solidarity with persecuted Jews. Bergson is often mentioned in this last regard, but other, less illustrious people felt similarly compelled. At the same time, some established French Jews sought to take advantage of exemptions that even the Vichy laws accorded to those who had “rendered exceptional service to France,” as the decrees stated. But no exemptions were ever guaranteed. While in the eyes of Vichy some Jews were less undesirable than others, in the end they were all members of the “Jewish race,” and their differences could become, as the occasion required, negligible.

One of the more shocking stories Semelin tells illustrates just how unpredictable and arbitrary the fate of individuals was. The Lyon-Caen family, who traced their presence in France to the eighteenth century, prided themselves on a distinguished record of service to their country. Pierre Masse, a member of the family who had earned several decorations for valor in the First World War, had served for years as an elected member of the National Assembly and was a senator when he went to register and get the “Juif” stamp on his identity card in October 1940. Masse knew Maréchal Pétain personally and had been among the parliamentarians who had voted to give him full powers in July of that year. This was not all that unusual, as many other Israélites supported Pétain at first, and, as we have seen, Berl even wrote some of his first speeches. For a brief period the celebrated writer and war hero Joseph Kessel also supported the régime, before joining the Resistance and eventually fleeing to London, where he played an active role in the circles around de Gaulle.27 After the publication of the Statut des Juifs, Pierre Masse wrote Pétain a letter dripping with pained sarcasm. Did the decree dismissing Jews from the army, he asked, mean he should tear off the insignia from members of his family who had died on the front in 1916 and 1940?28 The letter received no response. In August 1941 Masse was arrested in Paris and taken to the transit camp at Drancy. After several more transfers and failed attempts by friends to have him released, he was deported to Auschwitz on September 30, 1942, and died there the following month. He had been advised earlier to leave Paris and seek refuge in his country home in the Unoccupied Zone but had refused to do it. The distinguished jurist Robert Badinter, who recently wrote an homage to Masse, speculates that he may have been secretly counting on the personal protection of Pétain.29 Another member of the Lyon-Caen family, François Lyon-Caen, also counted on personal protection when he requested permission from the Vichy minister of justice to continue practicing as a lawyer at the Appellate Court in Paris. Permission was granted, but in August 1941 he too was arrested and taken to Drancy. He was deported to Auschwitz on September 2, 1943, and died there.30

At the opposite end of the social spectrum one finds similar arbitrariness. One family of poor Polish immigrants in Paris was saved after the husband had already fled south because the policemen who came to arrest him in July 1942 gave the wife and children a couple of hours to prepare for their own arrest—during which time the neighbors came and hid them, and afterward they too fled south. In another, very similar family during that same roundup the father was away working as a farm laborer for the Germans, but the mother and two daughters were arrested without being given a chance to prepare. The mother was deported, while the daughters were let go after a few months, and they and their father survived.31

Stories such as these, aside from their intrinsic interest, can help us understand more clearly Némirovsky’s situation during the two years that followed the Nazi invasion of June 1940. As her journal entry of June 6, which I quoted earlier, shows, she was not at all oblivious, to use Elisabeth’s word about her, to the realities and dangers that confronted her. Indeed, she monitored events closely, for she was planning her next novel, which she referred to in her journals as her “story about the French.” Although this sounds like Suite Française, it was actually Les Biens de ce monde, for which Némirovsky started writing notes in the spring of 1940 but which she didn’t finish until the next year. The novel traces the history of a salt of the earth type of French family of industrialists (no doubt inspired by Némirovsky’s friends from university days, the Avots), from shortly before the First World War until the outbreak of the Second World War. Given the heavy presence of war in the novel, her notes for it sometimes overlap with what would become Suite Française. They include details about the bombings and troop movements of June 1940 as well as accounts of the exode that she may have heard from refugees or followed through the newspapers, for she herself was already in Issy-l’Évêque in June. Tucked away among voluminous notes for the novel and miscellaneous ideas for stories are brief observations about her everyday life in the village. On April 24, 1941, when she and the family were still living in the local hotel along with a number of occupying German soldiers, she writes, “Today, rain, cold, yesterday snow. A room full of smoke. 6 or 7 silent men, polite and mild-mannered, are drinking beer and smiling at ‘Elissabeth.’ [This pronunciation of her daughter’s name indicates that the “mild-mannered” men in the room were Germans.] This morning, 2 prisoners taken away by 2 men with rifles. They gave them a quarter of an hour to get ready. French radio—idiotic ditties. I suppose French radio is meant for the amusement of children.”32 This last comment is Némirovsky at her most sardonic, a mood and a tone that alternate with anxiety and despair in these pages.

What did she do, faced with the dangers she was all too aware of? It may not come as much of a surprise, knowing what we know about her trust in the goodwill of elderly French men toward her and her writing, that among her first gestures upon learning of the anti-foreigner measures of Pétain’s government in July and August 1940 was to write to the Maréchal himself. After all, weren’t they both contributors to the Revue des Deux Mondes, shareholders in the company of French letters? Pétain, a member of the Académie Française since 1929, had contributed some articles of political analysis to the Revue in the 1930s. Némirovsky’s letter to him, dated September 13, 1940, could not have been more polite or more distinguished. Invoking as a start their common acquaintance with André Chaumeix, the editor in chief of the Revue des Deux Mondes, she quickly gets to the point: she is worried because she has learned that “your government had decided to take measures against stateless people [les apatrides],” and she and her family fall into that category—but, she adds, “Our children are French. We have lived in France for twenty years, without ever having left the country.” Monsieur Chaumeix will vouch for her, as will Monsieur René Doumic, the Revue’s previous editor, and his wife. The widow of another Académicien, Henri de Régnier, will do likewise. (Henri and Marie de Régnier were regular contributors to the Revue.) She goes on, “I have never been involved with politics, having written only works of pure literature.” And in all her works, published in France or abroad, she has sought to “make people know and love France.” Then comes the crux: “I cannot believe, Monsieur le Maréchal, that no distinction should be made between the undesirables and the honorable foreigners who, if they have received from France a royal hospitality, are aware of having done everything in their power to deserve it. I therefore request from your great benevolence that my family and I be included in this second category of persons, that we be allowed to reside freely in France and that I be allowed to exercise my profession of novelist.”33

Elisabeth Gille, who reproduces this letter in full in Le Mirador, presents it as having been written at Michel’s insistence, but it seems fully of a piece with Némirovsky’s behavior toward powerful men—and women, to the extent they existed—throughout the preceding decade. In seeking to distinguish herself and her family from the “undesirables,” she was reaffirming her sense of belonging to the class of respected establishment writers, a class in which she had actively and successfully sought membership. She was also anticipating what, unbeknownst to her, even the Statut des Juifs that would appear less than a month later would recognize, that exemptions could be given to Jews who had rendered “exceptional service to France.” Arendt, in articles she wrote around that time as well as later in The Origins of Totalitarianism, had cruel things to say about “exceptional Jews” who tried to evade the status of pariah that the world assigned to members of their religion. But it would take a peculiar self-righteousness to condemn Némirovsky for trying to save herself and her family by claiming exceptional status, in this instance not as a Jew but as a foreigner. The Vichy laws of that summer had made no mention of Jews, only of foreigners deemed undesirable, a legal category at the time. Némirovsky was insisting, quite rightly, that the label did not apply to her.

What is obvious today but was much less so in September 1940 is that all the rules she had successfully lived by for more than twenty years were changing, indeed, had already changed. The well-known names she invoked to remind Pétain that she and he were members of the same intellectual and cultural world no longer had purchase. A few weeks before her letter, on August 15, 1940, the Revue des Deux Mondes had published the text of a speech by Pétain on education, in which he made clear the new values that Vichy represented: “Work, family, fatherland” (Travail, famille, patrie), with an emphasis on “rootedness” (enracinement) and a refusal of “nomadism.” This text explicitly rewrote the slogan that had defined France since the Revolution: liberty would henceforth have to be “compatible with authority,” equality with hierarchy, and fraternity would be national.34 A month later, on September 15, two days after Némirovsky posted her letter to him, Pétain published another article in the Revue des Deux Mondes, in which he elaborated on this transformation. The new values espoused by his government were, he said, “purely and profoundly French,” while the others were “foreign imports.”35

It hardly needs to be said that Némirovsky’s letter received no reply from the Maréchal.

Meanwhile, her chief worry continued to be over work and money. Her surviving correspondence shows detailed exchanges that summer with the office of Albin Michel, which was being run by his son-in-law Robert Esménard in his absence. Esménard had written to her at the end of August 1939, just a few days before war broke out, offering to help in case she ran into trouble during these “anxious times that risk becoming tragic from one day to the next. You are Russian and israélite.”36 He would be pleased to attest, he wrote, that she was a writer of great talent, the author of critically acclaimed works, and that he had the highest personal esteem for her and her husband, in addition to his role as her publisher. One wonders, reading his letter today, whether he was trying to warn her or perhaps even to hint that she should look for ways to leave France, in which case she might need letters of recommendation for obtaining visas. This is sheer speculation, but it is striking how Esménard immediately zeroed in on her vulnerability: “Russian and israélite.” Curiously, Némirovsky the novelist was aware of this too, for in the novel she had just finished, The Dogs and the Wolves, the Russian Jewish heroine Ada, an artist, is expelled from France as an undesirable foreigner, a category already in effect under the Republic before the laws of 1940. But Némirovsky the individual person apparently did not see herself in that description. Even a year later, in August and September 1940, her letters to Esménard are only about the practicalities of living in Issy-l’Évêque: would the monthly stipends that Albin Michel owed her continue to arrive? On September 8 she writes to his secretary, “Some persistent rumors around here make me think that one of these days we may be part of the free zone, and then how would I continue to receive my stipends?”37 It is quite astonishing to see her worried that Issy might pass into the Unoccupied Zone, since many Jews were fleeing over the demarcation line precisely because of their desire to leave the Occupied Zone behind. But mail between the zones was uncertain, and she was obviously panicked at the thought of being left without an income. She and Esménard exchanged several letters that month. He writes on September 13 that The Dogs and the Wolves had not sold as well as expected, and he is therefore not planning to send any more money before his father-in-law returns. She replies very firmly, insisting on her verbal agreement with Albin Michel, according to which she would receive monthly payments of three thousand francs at least through January 1941. Esménard asks for more details on this agreement, and after she provides them he writes to her on October 2, “In view of the details you have furnished, I yield.” He would continue to send the stipends through December, he noted.38

The next day, October 3, the Statut des Juifs was published, less than a week after the German decree ordering Jews in the Occupied Zone to register. Irène and Michel obeyed the decree, even though they were Jews only by Vichy’s and the Nazis’ definition. Their identity cards probably perished with them, and there is no surviving fichier in the Saône-et-Loire departmental archives. We know they registered, however, not only by deduction—since they were deported they must have been classified as Jews—but also because from then on their names appeared on bureaucratic lists, some of which have been found. Since they were foreigners as well as Jews their residence now depended entirely on the German and French authorities. They were no longer free to move about at will, even inside the Occupied Zone. On October 29, 1940, Irène wrote in her diary, “At times, an unbearable anguish. Feeling of nightmare. Don’t believe in reality.” This is immediately followed by: “Absurd, fragile [? unreadable] hope. If I could just find a way to pull myself out of this [me tirer d’affaire], and my loved ones with me. Impossible to believe that Paris is lost for me. Impossible. The only way out seems to me to be the ‘straw man,’ but I have no illusion about the crazy difficulties that plan involves. And yet, I must.”39 Her idea of “pulling herself out of this” seems to have concerned the possibility of working, not of fleeing. The “straw man” solution, not spelled out, evidently consisted in finding someone who would be willing to act as the author of her works, so that she could publish and get paid. The journal entry continues with ideas for stories and reflections on the writer’s craft: “What was Poe’s manner? Absolute realism plus mystery.” She wants to write a story that will be a combination of Prosper Mérimée, the author of Carmen, and Edgar Allan Poe, she says.40

In December 1940, to her great relief, Horace de Carbuccia agreed to publish her work under a pseudonym. In his editor’s notes to her complete works, Philipponnat writes that before Gringoire she tried a Pétainist paper in Paris, Aujourd’hui, which refused the story she sent them. He quotes the letter she wrote to Carbuccia in which she asks for his help. The passage he quotes is from a later letter, but the fact is that Carbuccia did publish her work even after the exclusionary laws of October 1940.41 During the next year and a half, until February 1942, eight new stories by Némirovsky and all of Les Biens de ce monde, in installments, appeared in Gringoire, some signed as Pierre Nérey, her very first pseudonym from when she was twenty, and some simply as A Young Woman. Reading these on a microfilm of the newspaper is a sobering experience, for every issue of Gringoire in which her work appears—in fact, every issue of Gringoire at this time—contains vituperative articles against Jews, by Henri Béraud and others, as well as scurrilous antisemitic cartoons. Foreign Jews get the worst of it, but then Léon Blum, according to Béraud, is a “foreign Jew, the cause of France’s misfortune” (May 1, 1941). On May 9, 1941, the installment of Némirovsky’s Les Biens de ce monde is accompanied, on the same page, by a large advertisement for Signal, the Nazi weekly published in Paris.

Even more sobering, however, is to realize that Gringoire was by no means the worst as far as antisemitic journalism went in those days. It was far outflanked in viciousness and hate speech by doctrinal collaborationist papers like La Gerbe, Au pilori, Je suis partout, and others. In their study of antisemitic writing during the Occupation years, L’Antisémitisme de plume, Pierre-André Taguieff and his colleagues don’t even mention Béraud. Compared to the murderous rants of ideologues like Brasillach, Rebatet, Céline, Henri Coston, and Pierre-Antoine Cousteau, Béraud’s vituperations were perhaps merely ordinary.42 The sad truth is that in the France of the early 1940s no newspaper that expressed any disapproval of Vichy decrees or of its institutionalized antisemitism could be published. This is not surprising, given that even juridical experts and the Conseil d’État, the country’s highest court, analyzed the anti-Jewish laws in learned detail, without a word of dissent about their legitimacy. But the fact that Vichy’s exclusionary antisemitism eventually overlapped with the genocidal variety of the Nazis shouldn’t prevent us from distinguishing them, as Taguieff argues.43

In December 1940 Némirovsky’s editor at Albin Michel, André Sabatier, who was the senior literary editor (directeur littéraire) at the firm, returned to Paris after his military service, and they resumed a regular, friendly correspondence. From then on, perhaps due to Sabatier’s influence but mainly because Albin Michel himself agreed to it, Robert Esménard no longer bothered her about her monthly stipends. He even advanced a lump sum of 24,000 francs, or eight months’ worth, when she asked him for that favor in May 1941. The latest round of anti-Jewish measures worried her, she explained, and she asked him to send the money to her brother-in-law Paul Epstein in Paris, in his name.44 Esménard did so, and he continued sending the stipends even when her account was far overdrawn: in March 1942 he wrote her that as of the past December her account showed a debit of 117,500 francs, or close to four years’ worth of payments. Despite this, he wrote two months later to say that, as she had requested, he was increasing the monthly stipend to 5,000 francs.45 As many commentators have noted, the publisher’s support of Némirovsky and, after her deportation, of her daughters, deserves great praise.

One thing Esménard would not or could not do, however, no matter how much she pleaded with him, was to publish her new works. She had written a novelized biography of Chekhov in 1940–1941, using Russian sources and enlisting Michel as her research assistant, plus, as she reminded both Esménard and Sabatier, Les Biens de ce monde was ready as well. She had even received a fan letter addressed to the anonymous young woman author from a reader of Gringoire, which proved that “you don’t need a well-known name” in order to be read.46 This was obviously a hint about a straw man. In fact, she had found a “straw woman” in the person of Julienne (“Julie”) Dumot, who had worked for her father and, before that, for the family of her friend Jean-Jacques Bernard. Dumot, who was then in her fifties—she was born in 1885—had had some schooling: her surviving letters show that she could write fairly correct French, and she was familiar with the ways of the upper classes that employed her. Her status as “dame de compagnie” was above that of a maid but below that of a secretary, a kind of general assistant and companion who could occasionally double as a nurse. In June 1941 the Epsteins invited her to live with them in Issy-l’Évêque, and she joined them a few weeks later. When Némirovsky wrote to Esménard in October, she named her “friend Julie Dumot” as the “author of the novel Les Biens de ce monde, of which M. Sabatier has the manuscript.” She added that Julie, being “indisputably aryan,” could also receive the monthly stipends, for Esménard had written that a recent German ordinance required all payments to “Israélite authors” to be deposited into a blocked account. A blocked account was of no use to her, she wrote him; therefore the moneys should be sent to her friend Julie, who would support her.47 Esménard agreed to this as well and exchanged some letters with Julie as the author of Némirovsky’s manuscripts.48 Nevertheless, and despite promises from Sabatier, neither the Chekhov biography nor the novel appeared in Némirovsky’s lifetime. (The biography was published in 1946 and the novel in 1947.) In September 1940 the Germans had published a list of forbidden works that must be withdrawn from circulation by their French publishers. Known as the Liste Otto, the list was named for the German ambassador in Paris, Otto Abetz. A quite haphazard collection of authors and titles, the Liste Otto was aimed at Jewish writers and at non-Jews who were considered hostile to Nazism. It was a hit-and-miss affair. Many Jewish authors, including Némirovsky, did not appear on it, and even among those that did, only some of their works were banned. This allowed Albin Michel to keep her already published works in print, and they sent her a detailed report on sales of various titles in April 1942.49 On July 8, 1942, the Germans published a second list, and this time they were more systematic. The list of authors and titles was almost as haphazard as the earlier one and Némirovsky’s name still did not appear on it, but it was preceded by a Notice that stated unequivocally: all works by or about Jewish writers in French, except for scientific works, were to be withdrawn from circulation. Presumably publishers knew who their Jewish authors were and were expected to comply, list or no list.50 It is not clear whether Albin Michel withdrew any of her previously published works at that time, but they may have hesitated to publish new work by her even before then, even with her straw woman as an alibi.

Aside from work and money Némirovsky’s big worry after settling in Issy was finding a place to live. The family lived in the town’s only hotel, the Hôtel des Voyageurs, for more than a year before finding an acceptable house to rent. During some of that time they shared space with German officers who were billeted at the hotel. It was around then, in December 1940, that Némirovsky renewed her correspondence with her old friend Madeleine Avot, now Madeleine Cabour. “My dear Madeleine, you will perhaps be surprised to see my signature,” she begins her letter of December 5, for “we have ‘lost contact,’ as the saying goes, for a long time.” It must be “four or five years, or longer” since Madeleine’s last visit to her in Paris, she adds. In the archives, the last written exchange between them dates to New Year’s 1931. She inquires after Madeleine’s family and mentions her own family’s stay in Issy, where they are “for now quite content from the point of view of food and heat,” although they miss Paris. Not a word about the Jewish decrees and how they have affected her. This was obviously an exploratory letter, to see whether Madeleine would respond despite their long silence. Tellingly, she signs it, and all the subsequent letters as well, with her full name, Irène Némirovsky or Irène Némirovsky-Epstein, not just Irène, as she had done twenty years earlier.51

Madeleine Cabour evidently responded very quickly, for on December 20 Némirovsky writes her a longer letter and thanks her. Madeleine must have described the family’s flight south from Lille during the exode. Némirovsky expresses her sympathy and writes about the exode as well: she was already in Issy in June, but Michel had spent three days on the road for a trip that normally takes a few hours. Their life in Issy is boring but offers the advantage of food and heat; her daughter Elisabeth, who is only three and a half years old, doesn’t know about running water or elevators but is no worse off for that. The older daughter, who is eleven, attends the village school, which is all right for now, but “the situation had better not stretch out, otherwise she’ll be good for nothing but herding cows, and as I unfortunately have no cows . . .” The tone is playful, of wry humor in the face of minor annoyances. It is hard to believe that the person writing this is the same one who in her diary speaks of worry, anxiety, and despair and who in her letter to Pétain expresses outrage at being excluded from the world of French letters.

Némirovsky apparently found her former tone of lighthearted amusement the one most suitable for her old friend. She wrote Madeleine four more letters, between March and September 1941. She asked whether Madeleine knew of a place to rent where she and her family were staying, also in the Occupied Zone, as the accommodations at the hotel in Issy were very uncomfortable. Madeleine evidently replied, proposing a house for rent (her part of this correspondence is lost), and Irène then sent her a whole series of questions: was there plenty of food, a good doctor, someone to cook and clean and take care of Elisabeth as needed? And how did one get there with a lot of baggage?52 Given what we know about the restrictions on foreign Jews, who needed permission to live anywhere and to travel, this seems like a strange exchange. Némirovsky behaves here as if she were free to live where she wanted and even writes in one letter, on March 17, 1941, that after two recent trips there she had decided Paris was impossible to return to with the children—as if she had a choice. Soon, however, the question of moving became moot, for, as she wrote to Madeleine in September 1941, she had finally found the house she wanted: it was comfortable, with a large garden, and they would be moving in in November.53

As far as travel was concerned, it seems she and Michel did both spend at least a few days in Paris in February and March 1941, although there is no trace of any official request or permission to do so. A letter dated 5 February from her to an unnamed person at her publisher, probably Esménard, whom she addressed as “cher Monsieur,” bears the indication Paris and mentions that she will be returning the next day to Issy. On March 27 she writes to Sabatier, “cher ami” (dear friend), her standard way of addressing him, and mentions Michel’s earlier meeting with him in Paris. Possibly things were still in flux in those early months of the Occupation, or perhaps they had obtained permission to travel from a sympathetic bureaucrat in Autun, where the personnel kept shifting: there were three different sous-préfets in Autun between fall 1940 and summer 1942. By late November 1941, however, she was explaining to Sabatier that in order to get to Paris she had to have the permission of the German authorities, asking him for his help and advice. If she wrote to the Kreiskommandantur in Autun to request permission, would that risk drawing their attention to her “humble person,” she wonders?54

At this point, one might be tempted to agree with Elisabeth Gille’s adolescent view of her mother’s blindness. Surely by the end of 1941 she should have realized that to try and save themselves the family ought to flee or at least to hide. She chose not to leave Issy, thought Elisabeth, “even though she had every opportunity to do so.” But that is obviously too simple, for Némirovsky’s opportunities were limited, and, as we have seen, no individual choice guaranteed safety. To flee, one had to cross the demarcation line, and that carried its own dangers for those without the right papers. Dozens of people, including many non-Jews, were arrested in the Saône-et-Loire each week while attempting to cross. The archives in Mâcon contain regular reports on this, with every name duly noted.55 As for hiding, which could also be more easily done in the Unoccupied Zone, the usual way was to obtain forged identity papers and rationing cards, not an easy thing for an entire family. Némirovsky’s letters to Madeleine indicate a state of denial—“I can live where I want”—but that may have been largely a matter of posturing to her friend. What does seem clear is that she and presumably Michel had made the decision to stay put come what may.

On one level she was hopeful, urging Albin Michel to publish her work, making arrangements for the “straw woman” and signing a lease for the house, but on another level she was ready for the worst. On June 22, 1941, the very day Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and declared war on his former ally, she wrote a long letter to Dumot, “Ma petite Julie,” stating in its opening sentence, “Learning that Russia and Germany were at war, we immediately feared the concentration camp.” In fact, that was why she had asked Dumot to join the family in Issy, she told her.56 The letter was meant to be given to Dumot at the Hôtel des Voyageurs in case Irène and Michel were “no longer here” when she arrived. The Epsteins had been living in the hotel for over a year: “It’s a modest little inn, but the owners are totally trustworthy. We are leaving with them a box containing a few pieces of jewelry. . . . The box will also contain around 25,000 Francs in cash.” Undoubtedly, Irène assumed the two girls would remain there even if she and Michel were taken away and that Julie would care for them. Her letter contains detailed instructions about the household on matters ranging from the girls’ doctors’ appointments and vaccinations to the purchase of wood for the fireplace of the house they had rented starting in November: “The house is not furnished, but we have made arrangements with Monsieur Billand, the carpenter, and with Maître Vernet [the no«[[?a id=”page_119”?]]»taire] to rent the necessary furniture. So you’ll just need to get in touch with them.” Julie should also be sure to find someone to tend to the garden, which would produce a lot of vegetables and fruit, and if she ran out of money she should sell the jewelry but “start by selling the furs you will find in our suitcases, and which you’ll certainly recognize.” Julie would recognize them because the furs belonged to Irène’s mother.57

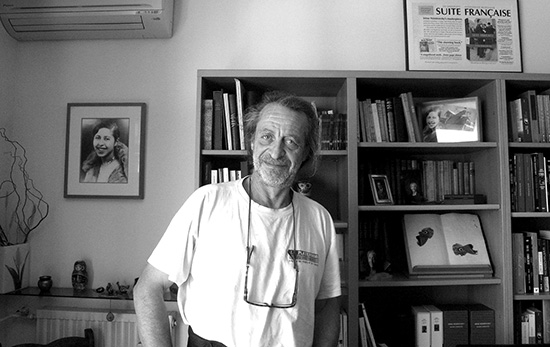

In short, the letter was a last will and testament. In the same mood, around this time Némirovsky deposited most of her manuscripts and writing journals, including those for David Golder and other early works, with the notary in Issy-l’Évêque for safekeeping. At the end of the year, hoping to get to Paris, she took them back, and they eventually found their way to a storage room at Albin Michel, where they were discovered more than seventy years later, in 2005, when the publishing house deposited its archives at the Institut Mémoires de l’Édition Contemporaine. These writing journals, added to the documents that Némirovsky’s daughters deposited in 1995, now form a crucial part of the Némirovsky papers at the IMEC archive.

Némirovsky’s letter of June 1941 to Dumot is important not only as a last will and testament but in another way as well. In it Némirovsky mentions for the first time that she has written a new novel she “[may] not have time to finish” titled “Storm in June.” She will leave it with the owners of the hotel, and Julie may be able to use it “in the last extremity” if she runs out of money. Irène writes that she has been in touch with the Editions de France, the publishers of Gringoire, to ask whether they were interested in publishing it. If so, they would write to Julie and pay a large sum for it, but otherwise her publisher Albin Michel would probably want it. This mention helps us to date the writing of Suite Française. It shows that by the end of June 1941 Némirovsky had completed at least the first part of the novel, the one titled “Storm in June,” and had possibly started on the second part as well. There is no trace of her letter to the Editions de France or to Carbuccia, who owned the press in addition to Gringoire. If Carbuccia had responded positively to her inquiry, we can be almost certain that the gripping story of the publication of Suite Française and all that followed from it would never have happened.

As it turned out, Irène’s and Michel’s worry about the “concentration camp” was premature, although only by about a year. To complicate things further, it appears possible that despite their detailed preparations for remaining in Issy-l’Évêque they may have attempted to leave France around the same time. This is suggested by a postcard preserved among Némirovsky’s papers, sent by a relative of Michel’s from New York in October 1944. Raïssa Adler, the widow of the celebrated psychoanalyst Alfred Adler (she and her husband had emigrated from Vienna to New York in the early 1930s), was related to Michel’s father and had visited the family more than once in Paris. Now she wrote to Irène and Michel, both of whom were long dead, “The last time I heard from you was through the ‘Red Cross’ in October 1941. . . . How much I wanted you to come to this country, but unfortunately I could not do anything about it.”58 Did Michel and Irène try to obtain an affidavit for emigration in October 1941? Maybe. Or perhaps they had simply written to her as a first step, for the International Red Cross had a service, still in existence, that put family members in touch across borders. I have not succeeded in finding any trace of the correspondence Raïssa Adler refers to. It seems certain, however, that Michel and Irène knew the president of the French Red Cross at the time, Dr. Louis Bazy, for after Irène’s arrest Michel wrote to him and also mentioned him to Sabatier as a person who might help to get her freed.59 But, according to the archivist at the offices of the French Red Cross in Paris, all of the correspondence files of Bazy and the other presidents of the organization from that period were destroyed in a fire, and only the minutes of the board of directors, recorded in bound notebooks, remain. The minutes contain their own drama, for even in their bureaucratic way they show the Red Cross’s efforts to maintain its independence in the face of German pressures. However, no individual cases are mentioned at these meetings.60

If Irène and Michel did make an attempt, no matter how tentative, to obtain emigration papers in October 1941, that would be an important piece in our puzzle, one more clue to the contradictory pressures that must have accompanied every decision they made at that time.

Unfortunately, other decisions were also being made, in Paris and Vichy and in Berlin, which would render all individual choices inconsequential. On May 13, 1941, over 6,000 foreign Jewish men living in Paris received polite convocations to present themselves at their local police stations, a development made possible by the massive registrations of October 1940. Those who showed up, about 60 percent (the others had evidently realized it was time to stop following orders), were immediately shipped off to the newly established internment camps in Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande in the Loiret region, not far from the historic city of Orléans and about 150 miles northwest of Issy-l’Évêque. Pithiviers had served as a camp set up by the Germans for French prisoners of war in 1940 and was now repurposed by the Vichy government to house foreign Jews. Beaune-la-Rolande, less than 15 miles from Pithiviers, was newly built. For about a year the prisoners were kept there, many of them put to work in adjoining farms and factories, which were shorthanded because French laborers were being sent to work in Germany. The prisoners established a kind of social life, with lectures, concerts, and theatrical performances, and they also set up various clandestine groups, hoping to organize resistance.61 But in the spring of 1942 all that changed. Over the course of a day’s meeting on January 20 in a leafy suburb of Berlin, fifteen Nazi officials convened by Himmler’s right-hand man Reinhard Heydrich had decided to implement the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.” Two months after the now-infamous Wannsee conference, on March 27, 1942, the first of more than seventy trains bound for Auschwitz left France from the station at Compiègne, with 1,112 men on board; 23 of them survived the war.62

Two months later, on May 28, 1942, the Germans published an ordinance that obliged all Jews appearing in public in the Occupied Zone to wear a “special insignia,” the yellow star, sewn on their clothing. Vichy obliged by sending out orders to all the Préfets in the Occupied Zone, who in turn sent out orders that all Jews in their jurisdictions who had registered in October 1940 were to be given yellow stars, the material for which was deducted from their textile rations.63 The following month, on June 25, the first of six transports from Pithiviers and the fourth to leave from France as a whole, with 999 men on board, left the train station, which was a five-minute walk from the camp. Three days later the first of two transports from Beaune-la-Rolande left with 1,038 people on board, this time including 34 women among the deportees. From then on women would make up a sizable number of all the transports. A report from the SS in Orléans to the SS in Paris explains that there were not enough male prisoners in Beaune-la-Rolande to make up the desired count of 1,000 per trainload, so they had arrested 104 Jews locally, among them the 34 women. Many of these people were French, not foreigners, and according to the report the local Préfet had tried to have them taken off the transport list, but his request was refused as per instructions from Paris. The author of the report noted that the “attitude” of this Préfet would be reported on in detail separately.64

Why this flurry of activity in late June 1942? Because the Germans and the French police were planning their biggest roundup yet of foreign Jews in Paris, this time including women and children. To make space for them before they were deported, the two camps in the Loiret had to be emptied of their longer-term occupants. The big roundup, notorious today as the Rafle du Vél d’Hiv, took place over two days, July 16 and 17. Altogether, 12,884 Jewish men, women, and children were arrested, and more than 8,000 of them, including 4,000 children, were taken to the huge cycling arena in Paris, the Vélodrome d’Hiver, where they lived for several days under horrifying conditions. No visual record of the interior of the Vél d’Hiv during those terrible days exists, but some testimonies by survivors have been published. The film La Rafle (The Roundup) (2010), directed by Roselyne Bosch, attempts to give a visual approximation of what this place was like, with no sanitary facilities and one doctor on the premises. After that, the detainees with families were transferred to Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande and from there to the transit camp at Drancy, a suburb north of Paris. Single prisoners were sent directly to Drancy. With few exceptions they all died in Auschwitz.

Meanwhile, in Issy-l’Évêque life went on almost as usual. The Epsteins and Julie Dumot moved into their new house in November 1941. Némirovsky had hopes that Albin Michel would soon publish All Our Worldly Goods, with Dumot’s name on the cover. She had started another novel that would span a French family’s fortunes from one war to the other, Les Feux de l’automne (Autumn fires). It was a hasty job, mashing together themes she had treated earlier in All Our Worldly Goods and in the two novels immediately preceding it, The Dogs and the Wolves, published in April 1940, and Les Échelles du Levant, serialized in Gringoire in 1939. Les Feux de l’automne repeats the chronology of All Our Worldly Goods, roughly 1910 to 1940, but its main protagonist is closer to the main characters in the two earlier works: young men who, even in the absence of war, experience the world as a battlefield where only the strong—the wolves, in Némirovsky’s recurrent metaphor—survive. One difference is that in the two earlier works the wolf characters are foreigners and are either explicitly or implicitly designated as Jews. In Les Feux de l’automne the protagonist, Bernard, is a Frenchman with no foreign ancestry. And for good measure Némirovsky added several dashes of Pétainist rhetoric to the mix. Thus Bernard realizes, after tragedy strikes his family, that the real causes of this terrible war were the “disorder” (a term used by some Pétainists to characterize the period before the National Revolution) and profiteering that had followed the last war, corrupting the souls of honest Frenchmen. Némirovsky was evidently hoping for a quick publication, preferably in a newspaper that would pay well, and we can surmise that the Pétainist touches were meant to please her presumed publishers. Her real feelings about the Vichy government are evident in Suite Française, where the narrator makes several sarcastic comments relating to it. In fact, Les Feux de l’automne did not appear until 1957, in the version she had in mind circa 1942. An Italian scholar, Teresa Lussone, has recently shown that Némirovsky deleted the most obvious echoes of Vichy themes before she died, and the latest version in her complete works respects those deletions.65

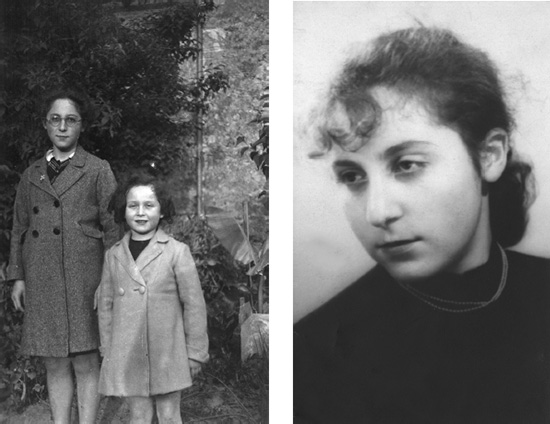

In January 1942 school resumed after the Christmas break. Elisabeth, now almost five, was enrolled for the first time. Her name appears in the school registry, which also indicates that Denise had earned her first diploma, the Certificat d’Études Primaires, the previous year. Irène, for her part, was hoping to be allowed to spend a few weeks in Paris. On February 11, 1942, she sends a letter, in perfect German and no doubt written by Michel, who was fluent in the language, to the Kreiskommandantur in Autun: “I am Catholic, but my parents were Jewish.” Her books have been authorized to be published in Paris, she explains, and she needs to see her publisher. Also, her daughter must see the eye doctor there.66 The following day, she writes to Hélène Morand, the wife of Paul Morand, in Paris, thanking her for sending her Monsignor Ghika’s address in Romania. But mainly she wants to ask Madame Morand for a favor: she really must go to Paris to deal with her landlord and her publisher and to see her oculist, but the current regulations forbid her to leave her residence. Would Madame Morand know someone who might intervene on her behalf with the German authorities, so that they would grant her a travel permit for one month? It may be useful for Madame Morand to know, she adds, that the authorities have granted her publisher permission to keep her works in print and to publish her new ones. Her Life of Chekhov is to appear soon.67

The Kreiskommandantur refused her request for permission to travel. Hélène Morand evidently replied, suggesting that Némirovsky ask Bernard Grasset for his help. Némirovsky wrote to thank her on February 25. She hadn’t contacted Grasset, she explained, because, as was well known, he was willing only to receive favors, not to do them. “If I succeed in escaping from Issy-l’Évêque, it will be a great pleasure for me to go and see you [in Paris]. My husband kisses your hand. Please give my best to Monsieur Paul Morand.”68 In the end Némirovsky sent Julie (who, being “aryan,” could travel freely within the Occupied Zone) to Paris in April with a list of errands, accompanied by Denise. Denise’s letters to her parents from that trip have survived along with a few Némirovsky sent to her. Denise wrote that she had a wonderful time in the big city with her uncle Paul.69

One wonders what Némirovsky had in mind, exactly, in asking Hélène Morand for help. She evidently knew, or imagined, that the Morands were in the good graces of the Germans, as participants in the Parisian salons where German officers regularly gathered with French writers and artists.70 In Storm in June, the first part of Suite Française, which she had finished by this time, Némirovsky heaps scorn on the bourgeoisie that found its way back to Paris with nary a qualm in the summer and fall of 1940. But in her life she was clearly willing to appeal to members of the same bourgeoisie to use their influence. She overestimated what they could do, however, and underestimated the single-minded ferocity of the Germans where Jews were concerned. Even Colette, who was part of the Franco-German salons in Paris, had no illusions about what to do to protect her third husband, Maurice Goudeket, who was Jewish. She succeeded in getting him freed after he had been taken to Compiègne in December 1941, on the same roundup as Jean-Jacques Bernard and other notables, but it took two months of maneuvering to do so, and after that she realized it was best not to ask for special favors from the “occupying authorities.” Goudeket wore the yellow star in Paris in June 1942, but not long after that he escaped to the Unoccupied Zone with false papers. He returned to the capital after the Germans occupied the whole country in November 1942 and spent the remaining twenty months of the war hiding every night in case the Gestapo came for him.71 Némirovsky, for her part, takes pleasure in informing Madame Morand that the Germans have allowed her to continue publishing even her new works, but she neglects to mention that those new works have been signed for by a third party and will not appear under her name. One of Némirovsky’s favorite books was Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The phenomenon of a double self, which that novel explores, seems pertinent here: one part of her knew things that the other part could not or would not admit.

Or perhaps she was still relying, like a reflex and despite many signs to the contrary, on the goodwill of people she perceived as powerful, who had done her favors in the past. On February 20, 1942, thus probably before she heard back from Hélène Morand, she sent a long letter to Carbuccia in Paris, a draft of which survives among her papers, with many crossings-out that show her hesitations. As she had done with Morand, she begins by reminding the editor of Gringoire of his kindness to her in the past and then launches into a heartrending cry for help. She starts a sentence but crosses it out in the middle of a word: “Je suis seule et désem” (I am alone and lost at). The incomplete word is “désemparée,” which translates literally as “lost at sea.” Then she starts again: her husband, who once held an important job with a Parisian bank, is now out of work, so they live entirely on her income. But the “recent laws” forbid her to publish in journals and weekly newspapers, and yet the German authorities have allowed her to publish her new works, and the Life of Chekhov will appear very soon. However, from a material point of view this will benefit above all the publisher, who has already given her significant advances. Thus, only new publications in the press will allow her to make ends meet. Then she returns to a theme she had already touched on with Maréchal Pétain almost two years earlier: certain Jews, among lawyers and doctors for example, are exempted from the regulations for “professional merit,” and does she not deserve to be among them? She has always refrained from politics, writing works of pure literature, and has even refused honors proposed to her. She says she turned down an offer to be awarded the Légion d’Honneur. But now she needs help. “You alone, dear Monsieur de Carbuccia, with the influence you possess and the position that has always been yours, can, if you wish to do so, intervene on my behalf with the government.” The government in question here is Vichy, not the Germans. If the government granted her the authorization, and “made it public,” then the editors of newspapers that had published her in previous years would certainly accept to publish her again, either under her name or under a pseudonym. And then, the ultimate plea: “You know me, you know that I have never asked for anything, happy to live simply from my work, but frankly I don’t know where to turn anymore: all the exits in sight seem to be blocked. It’s so cruel and unjust that I can’t help believing it will be understood and I will be offered help.”72

Carbuccia replied, in a typed letter on formal stationery, on March 17: “In the Unoccupied Zone, a ministerial decree forbids weekly papers to solicit the collaboration of Israélites, but the fact that the German authorities have authorized your publisher Albin Michel to publish and reissue your works will allow me to submit your personal case to the French authorities in Vichy. As soon as I have a reply, I will not fail to write to you.”73 No other letters from Carbuccia are to be found among Némirovsky’s papers, but he may have written to her bearing bad news, for two months later, on May 17, she writes to André Sabatier about “the state of bitterness, fatigue and disgust that I find myself in, and that the response of H. de Carbuccia only exacerbates, as you can imagine.” After February 1942 Gringoire no longer published her work, and it appears she didn’t even try to send them anything.

Rereading her letter to Carbuccia, in which she again emphasizes the injustice of not being recognized as exceptional, I am suddenly reminded of a scene in the Hungarian director István Szabó’s powerful film Sunshine (1999). The protagonist, an Olympic fencing champion from a Jewish family who had converted to Catholicism as a young man in order to be allowed to join the army officers’ fencing league, finds himself with other Jews in a forced labor camp during the war. He is wearing his officer’s jacket, and when a Hungarian gendarme guarding the group sees this he barks an order at him: “Take it off, Jew.” Instead, the prisoner states his name and qualifications: “I am Iván Sors, Olympic fencing champion and officer in the Hungarian Army.” This so infuriates the gendarme that he strips Sors naked and strings him up by the arms on a tree in freezing rain, ordering him to identify himself as “Jew.” Sors continues to repeat his name and his status as a Hungarian officer, until he is turned into a block of ice. His teenage son, paralyzed by fear and horror, watches from below.

This scene does not, in my view, condemn Iván Sors for his refusal to call himself a Jew. Rather, it suggests that for a man like Sors, who has worked all his life to bring honor to himself as well as to a country he considers his homeland, to be stripped of his name and titles is worse than death itself. What he refuses is not to call himself a Jew but to define himself as nothing but a Jew, a Jew reduced to anonymity as part of a mass. I believe that Némirovsky’s continued insistence that she deserved to be recognized as exceptional for her achievements and her service to France had a similar basis.

There was also the fact that technically she was no longer Jewish, but that is secondary. She had registered as a Jew in October 1940 since that was how Vichy defined her. But she wanted to be recognized as more than that: as Irène Némirovsky, a celebrated novelist. And if the authorities wouldn’t do that, she would still continue to write, not for money but for the honor of her name. This explains the tenor of her last letters to Sabatier, written between May and July 1942. He had come to visit her in Issy for two days in March, a sign of his devotion, for the trip by train from Paris was quite long and involved several changes, which she detailed to him in a letter on March 23. It was on that occasion, very likely, that she gave Sabatier all the manuscripts she had repossessed from the notary and that now constitute the bulk of her surviving papers. On May 4 she writes to him that soon Julie will send him a story he can submit to a journal that had shown interest in her work, which should be published under a pseudonym. But there is also the matter of the novel they had talked about. If the project is still on, then Julie will work on it, but she has to be certain that “it will be published soon, and well paid.” This may be a reference to Chaleur du sang (Fire in the Blood), a short novel that was discovered and published only in 2005. Then she goes on, “For otherwise, she prefers to continue with what she has been working on for the past two years, a novel in several volumes that she considers to be the most important work of her life [l’œuvre principale de sa vie]. And that one, I assure you, will be published only in circumstances and conditions she judges to be favorable.”