George Washington, the man who led the fight for American freedom, was a slave owner. At the age of eleven Washington inherited ten human beings, and he would own people his entire life. By the time Washington was born, African people had been enslaved in the Americas for hundreds of years.

According to Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, maintained by Emory University, between the years 1501 and 1866 an estimated 12,521,300 Africans were forced onto slave ships that sailed to different destinations. Full ships set sail with their human cargo, who were shackled together in horrendous conditions belowdecks. Over the years, an estimated 10,702,700 people survived the voyage (almost 15 percent died), and of them, approximately 388,700 (3.6 percent) arrived in mainland North America—part of which would eventually become the United States. The majority (approximately 95 percent) were sold to slave owners in the Caribbean and South America, while approximately 8,900 (0.08 percent) were sent to Europe and about 155,600 (1.5 percent) were taken to other locations in Africa.

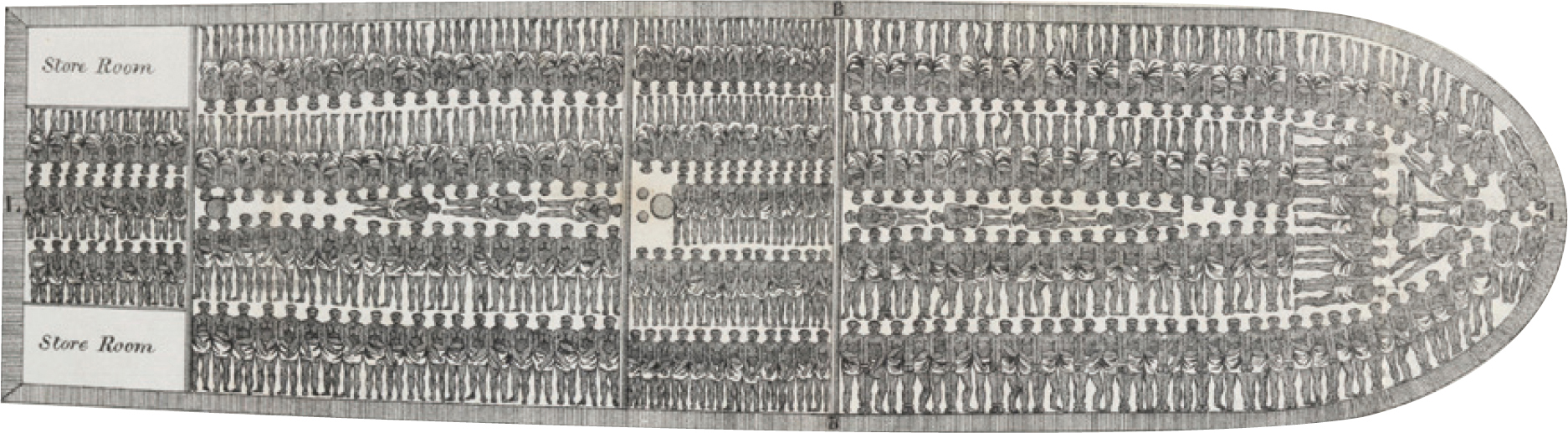

Enslaved human beings were packed into ships as cargo during the transatlantic slave trade. This is a 1788 diagram of the British slave ship Brookes (also spelled Brooks). That year, the British government limited the number of enslaved people who could be transported on each ship based on its capacity, and the Brookes’s limit was 454. However, the previous year, 609 enslaved people (about 349 men, 126 women, 91 boys, and 43 girls) were taken from west Africa and forced belowdecks on the Brookes. By the time the ship arrived in Jamaica where they were to be sold, 19 of them had died.

Abolitionists used this diagram to illustrate the horrific reality of slavery, including Thomas Clarkson, who had two models built of the Brookes. William Wilberforce, a British politician, used one of the models to show members of Parliament when he spoke out against the slave trade.

Those taken to North America were delivered to ports in both Northern and Southern colonies (which later became states). Abused and frightened, the men, women, and children who lived through the crossing were then taken to slave auction houses and put on public display. White potential buyers looked them over as if they were cattle—property to be bought and sold. At these public sales, African people were auctioned off and sold to the highest bidder. From that point on, they were the permanent property of the one who purchased them.

The buying and selling of human beings in this way is called “chattel slavery.” Enslaved people were considered chattel—the personal property—of the one who owned them. Like any other type of property, they were bought, sold, traded, rented, and inherited.

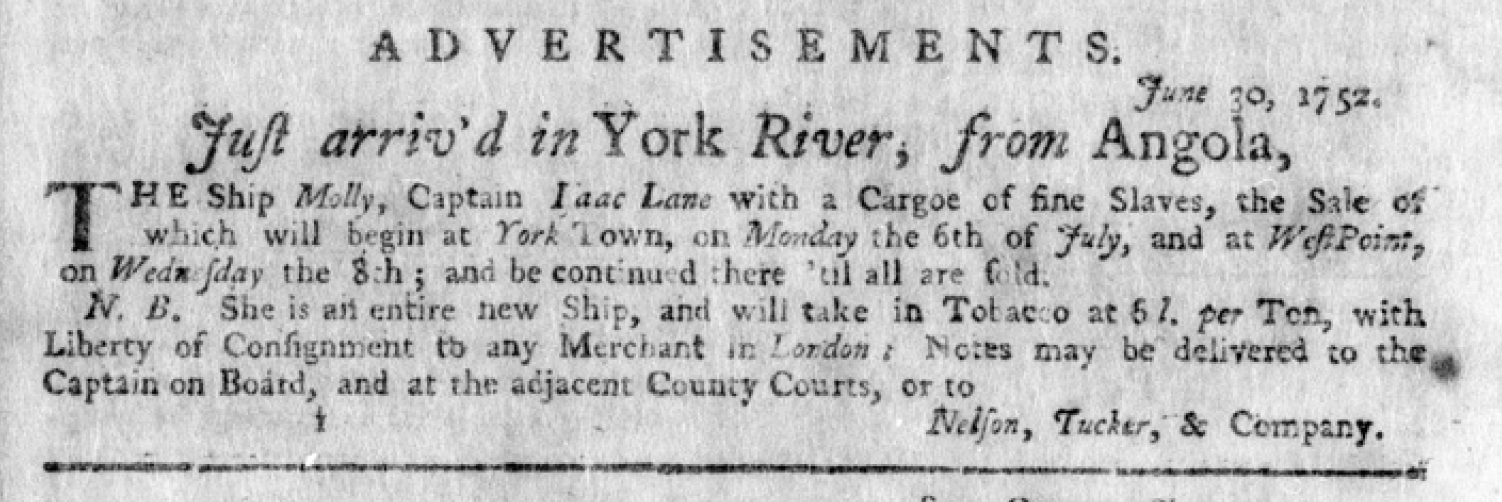

This newspaper ad for a “Cargoe of fine Slaves” from Angola appeared in the Virginia Gazette on July 3, 1752. The sale took place in Yorktown, Virginia

Regardless of whether a person was captured in Africa and brought to the colonies or was born into slavery in the Americas, he or she was forced into servitude. No one chose to be enslaved.

That certainly held true for the people who were enslaved on George Washington’s Virginia plantation, known as Mount Vernon.

The title of this book, Buried Lives, refers to the people George Washington enslaved in two ways. The first way is that while Washington’s life is well documented, the compelling lives of the people he owned, and the valuable role they played in the history of America, are largely buried under layers of time and history. This book seeks to shed light on some of these life stories.

The majority of enslaved people in America were not permitted to learn how to read and write. A few who lived at Mount Vernon could, but unfortunately none of them left a written record of their lives. Still, information is known about the enslaved community at Mount Vernon because a wide variety of historical documents, written by George Washington and others, exist that reveal details about their lives. These primary source documents are the foundation of my research for this book.

The second way this book’s title refers to the enslaved community of Mount Vernon is more literal. It concerns the final resting place of those who are buried there.

Two very different burial sites exist on the grounds of the former plantation. In life, the Washington family and the people they owned were worlds apart in their manner of living—and in death, the same holds true for their places of interment. George and Martha Washington each lie in a marble sarcophagus within a brick tomb. A short distance away, in the slave cemetery, graves are unmarked and their exact locations unknown.

But that is about to change. In 2014, archaeologists at Mount Vernon began a survey to reveal the location of each grave in the cemetery. It is their hope that this effort will, in part, help to connect the present to the past lives of the people buried there.

Of the hundreds of African Americans who worked at Mount Vernon, this book focuses on six people specifically: William Lee, Christopher Sheels, Caroline Branham, Peter Hardiman, Oney Judge, and Hercules. I’ve written about their lives and environments as accurately as possible. While there is much we can never know about their histories, what we do know speaks to us loud and clear.

The lives of the people in this book were intertwined with the life of George Washington, and vice versa. Nearly everything Washington did—where he went, the decisions he made, and in some respects what he accomplished—affected the life of every man, woman, boy, and girl who lived and served at Mount Vernon. And their forced labor—every meal cooked, every chamber pot emptied, and every crop harvested—affected the life of George Washington, because his lifestyle relied on the institution of slavery.

Washington was born into a slaveholding family. As a boy, he probably didn’t question whether slavery was right or wrong—it was part of life as he knew it. He likely didn’t know people who held anti-slavery beliefs until he was in his forties and became commander in chief of the Continental Army. It was then, during the Revolutionary War, that his friends John Laurens, Alexander Hamilton, and the Marquis de Lafayette spoke out against slavery. Because of the respect and admiration Washington had for these men, he listened. Slowly, Washington’s view of slavery began to change.

At the start of the war, Washington and the Congress excluded African American men from enlisting in the army. However, when the army needed more soldiers, they were allowed to enlist and fight in all-black units. Then Washington put an end to segregated units and ordered white and black soldiers to serve side by side. After Washington’s integrated Continental Army disbanded at the end of the American Revolution, it would be more than 170 years before full integration took place again in the United States military.

After the war, Washington’s views had altered to the point that he wanted slavery to end. In a letter to John Mercer in 1786 he wrote that it was “among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptable [sic] degrees.”

But while this was Washington’s private view, he did not publicly speak out against slavery, nor did he use his immense power and influence to work toward its abolition.

He was not unlike his successors in that regard. George Washington was neither the only founding father nor the only president of the United States who owned other human beings. Twelve presidents enslaved people at one time or another during their lives, including Ulysses S. Grant, the famous Union general of the Civil War, and Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence. After Jefferson’s death, 130 of the people he owned were sold at a public auction to pay some of his debts.

In contrast to Jefferson and other Founding Fathers who were lifelong slaveholders, George Washington eventually drew up a will instructing that the men, women, and children whom he owned were to be freed upon his and his wife’s death. Near the end of his life, he wrote, “The unfortunate condition of the persons, whose labour in part I employed, has been the only unavoidable subject of regret.”

His decision would affect the people highlighted in this book to varying degrees.