Long before the arrival of Spanish colonists, this part of the West Coast was a pastoral home to 30,000 Native American Indians. In 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese navigator in the service of Carlos I, king of Spain, was the first European to set foot in the area. But for the next two centuries LA remained nothing more than a pit stop on the trans-Pacific naval highway – a provisioning spot for Spanish galleons on their way back to Mexico from the Philippines. It wasn’t until other nations cast their eyes towards California that Spain decided to strengthen its claim on the region through colonization.

Founding Colonists

In 1769, Spanish colonists, led by two men, a 55-year-old Franciscan priest named Father Junípero Serra and Captain Gaspar de Portolá, arrived in San Diego and built the first of a string of missions up the coast to consolidate territories, extend borders, and bring Christianity to Native Americans. Natives didn’t take well to the new lifestyle, and diseases that arrived with the colonists killed so many thousands that the Native American population of California never recovered from the initial encounter.

In 1771, Mission San Gabriel Arcangel was founded, marking the first major Spanish presence in the Los Angeles area. It was the fourth in the mission chain and still stands 9 miles (14.5km) east of LA. Within the next few years California’s military governor Felipe de Neve decided the area needed a settlement and made plans to design a pueblo, or town. It took months to recruit any settlers, but in 1781, a group of 12 men, 11 women, and 21 children arrived at the mission from Mexico, and on September 4 they ceremoniously founded the new town ‘El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciúncula’ (Our Lady the Queen of the Angels of Porciúncula). Today the site is better known as Downtown’s Olvera Street.

Prosperity came slowly. In 1800, the population was 315. The pueblo included 30 homes, a town hall and guardhouse, granaries, a church, a central plaza, and 12,500 cows.

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

David Dunai/Apa Publications

The California Ranchos

De Neve’s successor passed new laws enabling him to grant vast tracts of land and grazing rights to settlers. He distributed tens of thousands of acres, largely to his friends and comrades. It was not long before a dozen or so patrones (landlords) owned nearly all of what is now coastal Los Angeles County, with the exception of the mission lands and the farms surrounding the pueblo.

Because colonial powers controlled all trade in their territories, Mexico and Spain at first received the wealth of goods produced by the California ranchos (ranches or farms) and missions. But news soon made its way to the East Coast about cheap goods from the California settlements. With few Spanish ships or militia in the area to enforce colonial trading laws, Yankee ships began capitalizing on this lucrative market, ending California’s isolation.

Mexican Rule and American Annexation

After Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1822 and claimed California for itself in 1825, Spanish priests were ordered out of the region and missions lost their power. Commissioners were appointed to distribute 8 million acres (3 million hectares) of mission land and resources, most to powerful families and ranchers. The Native Americans, having lost their lands, either fled to the mountains or found themselves having to work for Mexican landlords.

Meanwhile, the pueblo of Los Angeles had become the largest settlement in the territory, with a population of nearly 1,250. A number of Americans had settled in California, joined the Catholic Church, and married into the area’s leading families. Within a few years, these Americans became great landholders and wielded a monopoly on local commerce.

By the time war erupted between the United States and Mexico in 1846, agitators in Washington were already calling for the annexation of California. The Mexican settlers put up a good fight, against forces several times their number. Eventually, they were defeated, and in January 1847, General Andrés Pico relinquished Los Angeles to the Americans.

Miners in the 1850s Gold Rush

Getty Images

After the Gold Rush

Growth was still slow, but the discovery of gold in northern California in 1848 changed everything. Many Angelenos packed their bags and headed out to dig; those who stayed found a lucrative market in supplying food and goods to miners. Meat replaced hides and tallow as the main industry of the ranches; cattle were herded north where they could be sold for ten times the going rate.

On April 4, 1850, the city of Los Angeles was incorporated and declared the county seat. Its first newspaper, The Star, began in the same year, published in both Spanish and English. Over the next 20 years, Los Angeles gained a reputation as a ‘bad’ town, with the largest number of gambling dens, brothels, and saloons per capita in the West. But new industries sprang up: wine became an important export; the first citrus trees were planted; and a water-supply system was installed. Los Angeles began to lose its frontier-town aspects.

The Boom Years

By 1870, Los Angeles’ population numbered 5,614. Hotels and larger buildings were constructed; civic and cultural institutions such as a library, a dance academy, and a drama society were founded. Further prosperity followed the completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad line to Los Angeles in 1876, making the vital transcontinental link and sparking the biggest real-estate boom in the nation’s history.

As the large ranchos were gradually divided, settlers planted orchards and gardens and introduced modern agricultural methods. Oranges became one of the major crops, when refrigerated rail cars arrived.

In late 1885, the Santa Fe Railroad line reached Los Angeles, competing with the Southern Pacific in a fierce price war that made cross-country travel virtually free. By 1887, trains had brought more than 120,000 to the town of 10,000 residents; most of the travelers settled in the area.

The real-estate boom collapsed three years after it began, but by the time the dust settled in 1890, Los Angeles had embarked on a new campaign designed to lure Midwestern farmers to the sunny state. California’s prize agricultural produce was vigorously promoted, and people poured into the area believing the motto the city still promotes: ‘LA is the place where fortunes are made and dreams come true.’

The discovery of petroleum in 1892, not far from the city center, prompted another flurry of development and added a few more names to the growing list of ultra-wealthy residents. The first well, drilled by Edward Doheny and Charles Canfield, yielded 45 barrels a day. Within five years nearly 2,500 wells had been sunk within the city limits, and the industry flourished. Led by Los Angeles, California produced a quarter of the world’s oil supply right into the 20th century.

The 1890s marked further expansion with the construction of San Pedro’s deep-water harbor. Port of Los Angeles, the largest man-made port in the world, opened in 1910.

Small beginnings

With the rapidly expanding population, Los Angeles city lots were bought up quickly and new communities were founded. One of these, created by Horace and Daeida Wilcox when they subdivided their 120-acre (48-hectare) orchard, was named ‘Hollywood.’

The 20th Century

During its first 120 years, Los Angeles had become a dynamic city with a population of more than 100,000. But with a new advertising venture that included the slogan ‘Oranges for Health – California for Wealth,’ the population of the city tripled in the first decade of the 20th century.

One concern stood in the way of further expansion: water – or, rather, the lack of it. As the population mushroomed, it became clear that the Los Angeles River, the sole source of water for the city, would not be able to support the city’s needs. William Mulholland, chief engineer of the Municipal Water Bureau, planned to obtain water from the Owens River, which was fed by snow-melt from the High Sierra. In an amazing feat of determination, an aqueduct more than 233 miles (375km) long was constructed to deliver enough water to supply a city of 2 million. As an added benefit, a hydroelectric generating plant was completed along the aqueduct in 1917. In 1923, with the population rising by 100,000 each year, it was clear that an additional supply of water would soon be needed. Mulholland began to survey a route for a waterway from the Colorado River, 400 miles (644km) away in Arizona. The new aqueducts opened in 1939.

Mulholland’s drive

In 1924, LA honored water engineer William Mulholland by naming scenic Mulholland Drive after him. His work had given the city a reliable water supply. But 1928 brought disaster. A dam 40 miles (25km) north of Los Angeles collapsed only hours after he had inspected it, killing 450 people. Mulholland resigned in disgrace.

William Mulholland – the man who built the city’s water infrastructure

Public domain

After World War I, LA became the fastest-growing city in the United States. The metropolis soon stretched from the southern harbor at San Pedro to the San Fernando Valley in the north. A streetcar system began operating in 1901, and by the late 1930s had become the largest in the US, servicing some 80 million passengers a year. Citrus crops accounted for a third of the county’s produce. It was the nation’s richest agricultural region. Large oil refineries were built, and with the coming of Firestone and Goodyear, LA also became a major rubber-producing center, which seems especially appropriate, considering its residents’ already-established love affair with the car. Later, aircraft and car assembly plants were built. No single business, however, was – or is – as enduring in Los Angeles as the motion picture industry, which in 1919 was already making 80 percent of the world’s supply of films. It has remained the city’s chief industry.

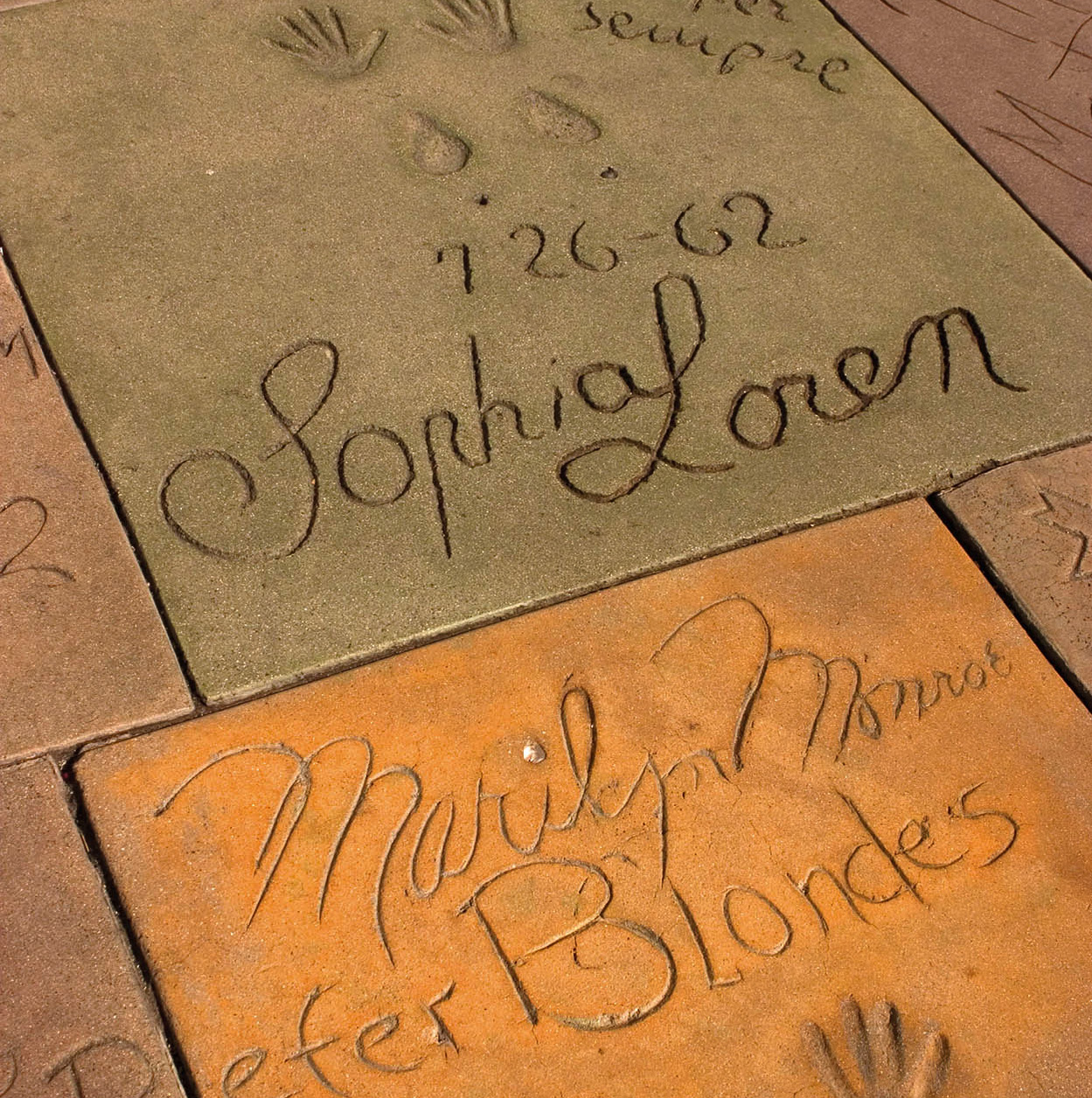

Hollywood Walk of Fame

David Dunai/Apa Publications

In the 1920s Los Angeles was a boom town and a melting pot for immigrants, hustlers, adventurers, desperados, and dreamers. Institutions appropriate for a burgeoning city were built, including Downtown’s historic Biltmore Hotel, the Central Library, City Hall, and the University of Southern California (which was founded in 1880).

When the Great Depression struck in 1929, southern California’s growth slowed as dispossessed farmers of the Dust Bowl region (the south-central United States) and a long line of other not-so-welcome migrants headed west. But by 1935 the city was optimistic, recovering economically, and ranking fifth among the industrial counties of the US.

Filmed in Hollywood

Movies found a home in southern California because the sunny days and wide-open spaces were perfect for filmmaking. Cecil B. DeMille set up the town’s first movie studio near Highland and Sunset in a horse barn and filmed The Squaw Man, the first feature-length film, in 1913. In the 1920s a box-office boom, led by such Hollywood stars as Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, and Mary Pickford, made movies a lucrative business. By 1939 cinemas outnumbered banks, and Americans spent twice as much time at the movies as they do today.

In the latter part of the 20th century, the Hollywood area’s golden history was tarnished by decay as the studios and stars moved out and an ongoing parade of hustlers and lost souls, souvenir shops and touristy attractions moved in. But since the millennium, an extensive renovation program has brought shiny new attractions and entertainment venues that will ensure the city’s encore performance.

World War II brought further growth in industry and population, as workers flocked to LA to find jobs at aircraft plants and shipyards. Close to 200,000 African Americans moved into south-central LA to pursue job opportunities. Mexican residents, who had not been so welcome after the end of Mexican rule, were also accepted as laborers. But overcrowding, prejudice, and already obvious social ranking would continue to cause great tensions.

With the postwar population boom and the phaseout of LA’s streetcars came the mass construction of today’s freeway system, making possible the development of areas previously considered too remote. Along one of these freeway routes in Orange County was another major construction project, Disneyland, which was surrounded by orange groves when it opened in 1955.

City of Los Angeles Police

David Dunai/Apa Publications

The Watts Riots

By 1963, California had become America’s most populous state. More water shortages, reduced services, and increased racial tensions resulted. In the summer of 1965, widespread rioting broke out in the black ghetto of Watts, in south-central LA, when a black motorist was accused of drink-driving. Six days of vandalism, looting, and fires left 34 dead and caused $40 million in damage. The scene was repeated in the spring of 1992, when the acquittal of four white policemen accused of beating black motorist Rodney King sparked 48 hours of riotous violence. The death toll reached 50, with thousands injured and property damage of over $1 billion. While other trials (O.J. Simpson’s murder trial in 1995, for example) divided the city, others, including recovery from the 1994 Northridge earthquake, brought Angelenos together as a community. A strengthening economy in Southern California has helped as well.

By the 1980s the growth of the metropolitan region forced city planners to begin rebuilding a system of public transport. A new light rail line, the Metro Blue Line, opened in 1990, connecting Downtown to Long Beach. The Red Line, the first subway, opened Downtown in 1993, and now stretches all the way to North Hollywood. The Green and Gold light rail lines, opened in 1995 and 2003 respectively, were joined in 2005 by the Orange Line, a dedicated bus transitway through the San Fernando Valley, and in 2006 by the Purple Line subway, serving west of Downtown. The latest addition is an extension to the Expo Line to the west with seven new stations linking Santa Monica with Downtown in under 50 minutes.

LA Forever

Los Angeles’ sprawl has made creating a unified ‘city’ impossible. Though the entertainment industry and its revenues reach businesses and residents from Downtown to Malibu, in almost every other way each neighborhood is its own mini-city struggling for a sense of itself. Los Angeles County with a population of over 10 million is facing the challenges of the 21st century as well as the perennial problems of soaring prices for energy and basic necessities. But that doesn’t prevent Angelenos from looking on the bright side. Business is booming; the beach is packed; and movie stars and millionaires are still made overnight.

String of pearls

Each of the 21 missions established by the colonists lies a day’s horseback journey apart in a line (the ‘string of pearls’) that stretches between San Diego and Sonoma, 600 miles (966km) to the north.