WOMEN BREADWINNERS-IN-CHIEF AT HOME

When Professional Life Meets Intimate Relationships

When I first started thinking about the idea for this book, I knew that I would have to write this chapter. I was scared then; I’m scared now. I know that there is a large delegation of successful, professional women who would probably prefer to talk about their adventures in mammography rather than to wade into the mucky territory of how their work life has impacted their marriages or partnerships—and how their mates have affected their careers. I completely get it. It’s uncomfortable. It’s fragile. It’s personal. I mean, our families are supposed to be perfect, right? Isn’t that the one true definition of a happy woman? Isn’t it all supposed to look and feel so easy for all of us? In truth, none of our families are perfect, and I know that if I can’t talk about my own struggles and share my conversations with successful working women about theirs, then I can’t honestly talk about knowing and growing your value.

Simply put, I’d be a fraud. For me to say that I have found the path to true success in life by sticking to some map that other women and I had discovered would be nonsense. There is no map. No one knows the route. Don’t believe people who say that there is one. What I, countless other professional women, and you do have is our experience and our reflections. Those are priceless, and it’s important for us to share them with each other. Eventually they may all combine to create a map, illustrating a number of routes that will get you to where you want to be: a place of true success where your personal and professional selves gracefully overlap each other.

But what the data shows is that we’re not there yet. Women breadwinners are growing in epic numbers, certainly. According to a 2013 Pew Research Center analysis of data from the US Census Bureau, an unprecedented 40 percent of all American households with children under the age of eighteen are supported by mothers who are either the sole or primary source of income for the family. They’re not having an easy time of it (and I’ll get into our poll results on that momentarily). But I also want to share with you what my experience has shown me and what my conversations with successful working women have shown. And that is: as our professional lives and professional values grow, the dynamics—even the language—of our closest connections with our most intimate companions are reshaped, upset, and transformed. Sometimes drastically. If we began our relationships early as young adults, we are, in many ways, no longer the same women we were when we first met our partners.

For some couples these changes are positive. For them the shifts in positions, outlooks, and responsibilities have allowed both partners to occupy roles in their relationship that are unique and perfectly suited to them. But there are many of us who have been blindsided by the unexpected emotional fees and taxes attached (often, in vague, passive-aggressive print) to our rise in professional success.

That’s another reason why this chapter scares me. I’m going to put myself out there, and I’m going to share discussions with other women who put themselves out there too. We have to do it. This tension in relationships is becoming a cultural issue. We’re living in a unique time in American history. Not only do most women work now, but they’re also surpassing men in education and salaries. In particular I think women who make more than their husbands have unexpected challenges, and data exists that shows that, even in our postfeminist, egalitarian democracy. So if we don’t start a national conversation about this now, it’s going to hurt our children later.

AND THEN I GOT A RAISE

My husband, Jim, and I have always had a marriage of equals. We’d both grown up as children when the Women’s Movement and ERA were in full swing. We worked in the same field. Jim and I have always been in the television news business. In fact, as I mentioned earlier, that’s how we met, in our twenties, working at a local news station in Hartford, Connecticut, where Jim was hands down the most thorough, smart, analytical investigative reporter in the pack (and still is).

From the beginning of our relationship and marriage Jim and I were always working breakneck deadlines, often passing each other like speedboats in the night. We understood and respected each other’s work ethic. We supported each other. We still support each other. But over the past several years my professional presence and persona have gotten to be increasingly public. I started making more money than he did. And then I got a raise. A big raise.

I didn’t tell him about it for two months.

Why? Why wasn’t I sharing this amazing news—the news of my professional lifetime—with Jim immediately? Why weren’t we popping open a bottle of champagne, screaming “Yippee!” and celebrating? I couldn’t tell him. I just couldn’t. I was paralyzed. As progressive and thoughtful as he unfailingly was and, again, as completely egalitarian as our marriage had been, I was inexplicably worried that this money and professional leap would somehow change things in our relationship. It would, somehow, upset our applecart. I worried it would hurt him.

As much as Jim had always lifted me up when I was down, something hard and tight in my gut told me that my news would not make him feel good. I worried that it would upset the natural state of things, the way they were and always should be. So I didn’t tell him for two months. Because of exactly how I felt when I did finally tell him. He looked stunned but immediately was congratulatory and happy, of course. As I’ve emphasized, he’s a supportive husband. But I could also tell he was surprised.

And I was shocked by how much it affected me and how guilty I felt. It made me feel as though I’d done something wrong. He did not make me feel this way. On the contrary, he truly seemed proud. But things were different in my head.

DON’T ENJOY, OR “MIXED BAG”

Why did I—why do I—feel guilty (if that is even the word)? Looking for some psychological insight, I asked the therapist I most admire and trust, marriage and relationship expert Dr. Jane Greer, what she sees when women start to outearn their spouses. “I’ve worked with quite a few couples where women have been more successful, either in the scope of their jobs or in greater income and financial status. And it isn’t always problematic to begin with. Very often the relationship starts when women are growing their careers and increasing their income potential,” she said.

“Oftentimes the competitive issues are more beneath the surface to start—while there may not be overt arguing, you can detect failures in supportive actions and behaviors. Usually partners will like the fact that their spouse is doing well financially, especially if there’s a certain equity with access to money and they’re both able to spend and enjoy it, enhancing their lifestyles. In that scenario, everybody’s happy. However, at some point an element of envy creeps into play around who’s doing what, who’s making what, and who’s calling the shots. That’s when the power and the control issues start to flare up.”

I never sensed this with Jim, but he doesn’t like the way my work monopolizes my mind and my time. He would be much happier with a lot less money and a lot more me.

According to our Working Women Study Poll of male and female breadwinners all across the country, two-thirds (63 percent) of female earners-in-chief say they don’t enjoy being the primary earner or that it is a “mixed bag,” compared with four in ten male breadwinners (38 percent). Female breadwinners are also less likely than male breadwinners to believe that being the primary earner has a positive effect on their relationships with their spouse/partner. The poll also reports that male breadwinners are more likely to say that being the primary earner has resulted in them having more respect for their spouse/partner. Female breadwinners are more likely to say that having this role has resulted in tension and arguments in the relationship.

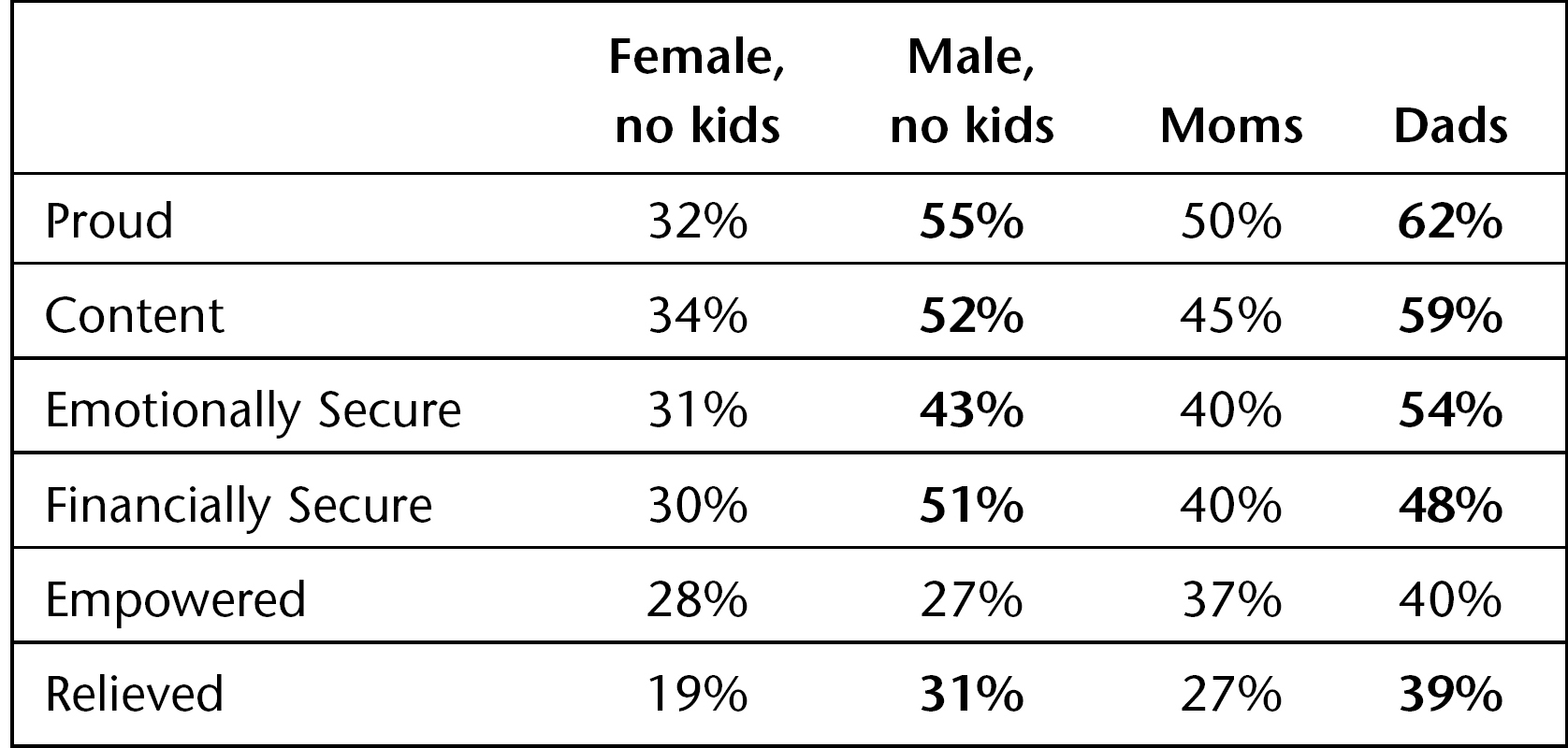

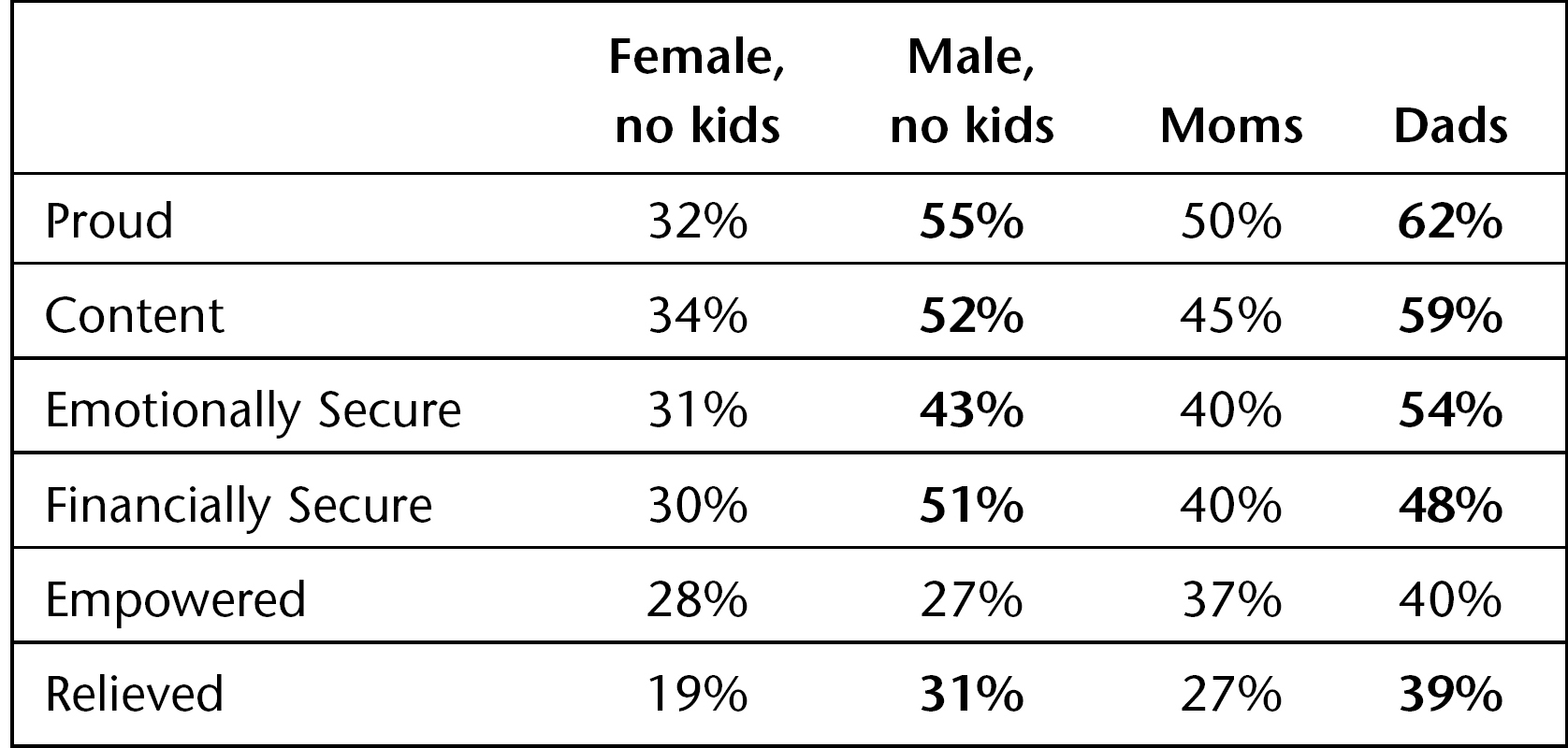

And when men and women were asked to respond to various adjectives describing their feelings about being the primary earner “extremely/very well,” the results, to me, were astonishing. Consider this chart from the MSNBC Working Women Study Poll:

Adjectives that describe how breadwinners feel about being the primary earner “extremely/very well”

There’s the heart of the beast, I thought, in big, bold numbers. The majority of male breadwinners, with kids or without, feel really positive about being the primary earner. The majority of women, whether or not they’re moms, do not.

When I look at this chart, part of me is completely incredulous. How can we not feel great about finally being at parity with and, in some cases, surpassing men professionally? Even though we know that women in general still earn less on average than their male counterparts, our arrival on the national stage as primary earners should be a call for celebration.

Actually, some women are more apt than others to feel good about that status. According to our survey, female breadwinners are more likely to say they feel “emotionally secure” about being the primary earner if they live in the Northeast (47 percent) rather than the Midwest (32 percent) or the South (33 percent). The Northeasterner in me understands that. But part of me is also sympathetic to how midwestern and southern women feel. Some of the verbatim responses from women who did not enjoy their role as breadwinner are hard to hear. “I know my spouse would rather support me, than me support him,” said one woman. “I do not enjoy the guilt, I do not enjoy the envy,” said another.

I do not enjoy the guilt; I do not enjoy the envy. I find that a poignant statement. So many of us seem to come to the table feeling so guilty about everything. Why? Or overly grateful. Why? Feeling guilty that you have kids as well as the job of senior vice president when your husband doesn’t make as much money as you. Why? Feeling as though you have to overcompensate as wife and mother when you get home because of the time you spend at work and because you make more money. Why? Feeling so grateful that you have this job, that you’re not getting the pay you deserve. Why should any of us feel this way?

Again the female breadwinners in our poll put it bluntly and succinctly. “I feel bad for my husband—he says he doesn’t mind, but I think he does. I feel responsible for the family by being the main ‘breadwinner’ and insurance carrier. I wish he was, and not me,” one woman said. “I’m proud to make good money as a woman, but it hurts my husband’s pride,” said another. “Longer hours leave little time for affection,” said a female breadwinner, speaking to the exhaustion of work leading to a lack of intimacy in a relationship. Or as another one just came right out with it: “Stress of financial responsibility, spouse’s resentfullness [sic] towards me.”

But this is the one that jumped off the page for me: “My husband feels like we are in a competition. He says it does not bother him, but I can feel the tension and the competitiveness.” I’m sure that my husband doesn’t feel competitive with me. But I think Jim feels that he has to compete for my time. That is, it’s enough for him that I have so many job-related responsibilities. It’s my other projects, my knowing and growing your value work—this book, for example—that he takes issue with. “You’re already making enough,” he says. “Why are you doing more?” He sees my investment in building this part of my life as an affront to the family. “That’s more important than us?” The questions hurt. The truth hurts.

We had a very serious talk, and his argument was that because I didn’t need any more money, then the “extracurricular” part of my career—helping women know and grow their value—must be an exercise in vanity. My response is that of course I don’t want to spend more time away from the family; rather, I do this work because I truly believe that I have finally found my calling. And more importantly because I believe I am building a platform that someday our daughters will stand on. In fact, I am doing this, in large part, because I am concerned about our daughters’ future as women in this culture and society. I want them to be able to flourish, to be exactly who they are and want to be in all areas of their lives. I also know that my professional value has a “shelf life,” and I know I need to save for a more secure future. This all sounds well and good and high-minded, but in Jim’s defense, building my brand and name recognition has involved many more red carpet walks, party appearances, and speaking engagements than perhaps this household needed. It took a lot of networking and bad scheduling decisions before this brand was clear and on its way.

When it comes down to it, I think my husband questions the contents of my inner value, which is exactly what I am doing too. He sees this part of my life as needless extra work—vanity, one more reason not to spend time with our family. I see it as my life’s work, where my experiences can be of service to a broad range of women. Personally, it’s where my professional value and an important aspect of my inner beliefs converge. It makes me feel useful, energized, and happy. It doesn’t have a thing to do with my love for him and our family. To be fair, Jim really admires the Know Your Value message, but it was all the things it took to get to this point that didn’t make sense to him at all—it leaves too little time for a real family connection.

Which one of us is right? Are either of us right? How do you even define “right” in this context? I don’t know, but I’m pretty sure of one thing: I don’t think a man building an enterprise would have these problems. Historically, this has to be a new problem. Mothers and wives are needed at home. We are in a bad position when we have to make these choices.

WE DIDN’T ENVISION IT

When I had my big sit-down talk with Dr. Judith Rodin, I asked about her thoughts and experiences on the subject. I felt there was a problem, I said, “as we break through as women, read-justing our own sense of ourselves so that we sell ourselves ‘right’ to our significant others. Because I think there are problems at home when a woman has professional power and financial success. Would you agree with that?”

Judith agreed immediately and then went even deeper. “Yes, but I think it starts earlier. We’re so programmed as young girls and young women to (a) want to be popular and (b) want to find just the right husband or just the right partner, more broadly. And we’re willing to present ourselves in ways that we think make the other person like or love us more. That’s the young person’s ‘disease’ in a way,” she said, interestingly. “It’s the insecurity and the immaturity and the lack of life experience that makes you do that.

“I think as women get older and they mature and they go through a period of both personal and professional experiences, they realize that they’ve got to present themselves to the romantic relationships as ‘This is who I am, and if it doesn’t work for you, we’re not going to work as a pair. It’s not that I’m not willing to compromise and do all the things that make any relationship successful, but I am not going to change who I fundamentally am.’ That’s wisdom and maturity that I wish more young women would have but that may only come with life experience and years. And so if you can help them understand how to incorporate some of that confidence and experience earlier, I think it has the potential to be transformational.”

I was fascinated that essentially she characterized people-pleasing as a disease. “How does that ‘disease’ exhibit itself in relationships and family troubles as a woman grows in her career, do you think?” I asked (and was afraid to hear the answer).

Judith was undaunted. “So in the beginning she’s so happy to be in this wonderful relationship and have a partner and feels like she’s on her life course on the personal side. And if she starts to develop professional successes, her confidence grows because of those in her working life and her concept of herself. And on this I can not only speak objectively; I’m speaking personally as well that the partner is often—not always, but often—threatened by that. ‘This isn’t the person I married. This isn’t the person I signed on for,’” Judith said. “And the partner’s correct! It isn’t that person anymore, so they either adjust together to their own transformations—which can happen, and wonderfully so—or they start to grow apart.”

But what does that really look like in a partnership or marriage? Examples? “There are the seeds of resentment where small slights become big grievances,” Judith continued. “You said you were going to be home at seven, and you were home at nine. And suddenly that’s a really big deal where it never would have been before. Because what you were doing in those two hours was something that was such a signal of your professional success and where you are going that it becomes a threat. But the fight isn’t really over that you were two hours late.”

“It’s like they become markers of how much you care,” I suggested. Judith agreed emphatically. “Exactly! Exactly. And that you are called more than you ‘should’ be to do what you’re doing in your work is sort of reframed as a marker that you’re caring less,” she ruminated. “So these little things become bigger things. It’s the threat around growth and maybe some threat around success.”

Boy, did I hear her on that one. You can scream, say it’s not fair, even blame it on a stubbornly sexist culture. Still, certain realities persist. If you have achieved some—or a lot—of success in your work life, there are consequences in your personal life. I am aware, for example, that my job takes me away from home quite a bit. I am aware that my husband is alone a lot. I am aware that I am probably moderating a panel during the parent-teacher conference or while my family is eating dinner. I am aware that by always being “on”—a high-gear mental state necessary to do the kind of rapid-speed, multitasking work I do—I am probably making my husband feel as if I’m working my professional “tricks” on him rather than slowing down and remembering who I am and connecting with him as his longtime friend and wife. As I write, it is clear to me that my own nerves and exhaustion are getting in the way of personal success.

When I asked her what that was like for her personally, Judith was frank and thoughtful. “I mean, I have been divorced, and I think that the relationship just couldn’t work,” she said. “We grew apart because our lives became so different and our success trajectories really diverged, and it was hard for both of us. He resented me, and I think I unintentionally demeaned him because he wasn’t going as fast as I was. So I think we were both guilty.” Then, she added, “And it’s so real. Just watch out for the little things that he picks on you for, because that’s such a sign of where and how he’s threatened. But on the optimistic side, I have since been happily married now for twenty years, to a real professional and intellectual partner who is my biggest fan.”

I’m on live television in the morning for three hours. Then, while my husband is at work, there could be something about me on the Internet; in our age of tweeting, blogging, and gawking, the buzzfeed is relentless, glamorizing, demeaning, always “on.” Then I’m on stage giving a speech, and there are pictures in the paper, on the web. I’m getting clothes thrown at me to wear on television or at events; I get gifts, tickets, and special invitations all the time. VIP treatment. I’m writing books and revealing a lot of my own life in the process. I feel that, to Jim—and he’s probably right—my job description has changed from “reporter” to “media personality” and that my work life has become celebritized. And celebrity doesn’t fly in our house. With anybody. Not even the dog is impressed.

I wondered about this aloud with Judith. “I feel like in some ways it’s natural for that feeling of threat to happen. Do you think that’s true?” I asked. “I don’t think we’ve ever seen so many women do so professionally well before. And maybe it isn’t just that the men may be threatened, but that maybe we didn’t envision this dynamic either.”

She jumped on it immediately. “Wait, when you say ‘we didn’t envision it,’ I want to stop there because I think that’s really important. You know, lots of us did well in high school and college, and we get to some point in our career and we ask ourselves: Can I envision what all of this is?” Judith said. “I remember sitting at my desk at Yale my first year there as an assistant professor . . . but I was fearful. I was waiting to be ‘found out’ that I wasn’t as smart as everybody thought. I wasn’t as creative as everybody thought. I have to say that I think a lot of women in the beginning both aspire but also are fearful. I know that was the case with me.”

But then, Judith said, she hit her stride. “For me, the turning point both maritally and in that feeling was that seven or eight years out after [my first year at Yale] I both won the American Psychological Association Early Career Award, which they give to a young person in psychology who they feel at the early part of their career has really super-distinguished themselves, and I got tenure at Yale. All in the same year,” she recalled. “It was amazing, and I realized I didn’t fear getting ‘found out’ anymore. But things were getting worse at home. And they were certainly correlated.”

THIS IS WHO I AM

Striking the right balance between communicating your energy and willingness to do the job as well as your personal style and passion is not just the first step in launching your career as a young woman, an entrepreneur, or both; it’s also the first step in growing your professional and inner value. It’s where you, as a package, cohere and make a good first impression on the world. It’s also a way to strengthen your sense of yourself and your capabilities. It’s about not only being a team player but also being true to yourself. In that regard, there will perhaps be no proving ground more intense than that of personal relationships. And as you start your career and life, getting your relationship off to the right start—being clear about who you are with your boyfriend, girlfriend, or partner from the start—is critical.

It’s simply too important to ignore. If you are ambitious for yourself, for your career, you’ve got to be clear about that in your personal life—and certainly with the person with whom you plan on spending it. If you can look a prospective employer in the eye and communicate what you bring to the table and what you’re willing to do, you should definitely be able to do that with your partner.

I think women need to come to this conclusion a lot earlier in life. This is a conclusion that entrepreneur Amanda Steinberg, founder and CEO of the women’s financial media site DailyWorth.com, also came to after years of thinking she wanted something else in her relationships. During a conversation at her home in Philadelphia she said that the kind of life that had been marketed to her as a girl and young woman involved being “saved” by a man. When that hadn’t happened by the time she reached her early thirties, Amanda realized that a big part of the reason was because she hadn’t been clear enough with herself that, in fact, that wasn’t what she wanted.

“About a year or so after I started my company, I was on my own, and I went through a period of being really lonely. But during that time I realized that I was okay being my own rock, that it would be great to be in a stimulating, nurturing relationship, but that I was never going to be okay with it if it meant I had to pretend I was someone I wasn’t,” she said. “And who I was and am is a very focused entrepreneur, driven by mission and ambition to take on the idea that women want to take charge of their financial lives and, therefore, their destinies—that we don’t need someone to do that for us.”

In her current relationship Amanda feels fully embraced for who she is authentically. “I feel seen and appreciated for who I actually am, and a lot of that is because my boyfriend is someone who understands and loves that, but it’s also because I developed the strength to be as direct with him about what makes me tick as I am with our investors and community about the guiding principles and goals of the company,” she said. “Does it mean that I’m always this bulwark of strength; an island? No. But it makes me a more conscious partner because now that I can feel comfortable in my own skin with my partner, I can be open to who he is and what he needs too.”

Still, I’m not saying that this is easy. I know that in my own life it hasn’t been easy. Had I always been transparent about my ambition with my husband? I thought I had. But maybe I hadn’t. Maybe I couldn’t do that until I’d had the experience to know who I was in terms of my professional value and my inner value. Maybe I wouldn’t have felt as though my professional value and my inner value were so detached from each other if I had been more honest about who I was and what I wanted from life. Maybe that was the source of the tension in my marriage. Maybe Judith is right: being able to know and articulate who you are—that is, to know and grow your own professional and inner value—is a byproduct of maturity.

The subject came up during my conversation with Senator Claire McCaskill. I wanted to know whether she thought there was any prescription or warning we could give young women about choosing a partner. I didn’t know what the advice should be except that women definitely need to choose someone who they think will grow with them—and I was not sure that was an easy thing to do. Senator McCaskill was very wise on the topic. Her advice was straightforward, outlining the chain of events likely to take place if you aren’t honest in your relationship.

“I think to some extent [telling young women they need to be honest about their ambition] puts a lot of pressure on young women who hear that, and some of that pressure is unnecessary. But I do think you have to know what you enjoy doing and drive toward it and then use that as your armor to try to foster your ambition,” she said. “For example, if you figure out you’re in a job and you’ve got five different jobs you do, and three of them you hate and two of them you love, then you’ve got to immediately start reminding everybody how good you are at the two you love so that you will then be seen as someone who can continue to excel in those areas, and in that way I think even very young women in their careers can begin branding themselves.”

But, Senator McCaskill pointed out, this can be easier said than done while managing a serious relationship or marriage. “I’m divorced and remarried, so I would never be so phony as to say that my career and my ambition have never been an issue in my personal or family life. Of course they have,” she said. “But I will say, in my marriage—and frankly that door swings both ways—that some of this was my fault. I’m not about to say that I have been a victim here. Sometimes my first husband was a victim because I was not as thoughtful as I should have been at very important times. So I learned a lot from my failures in my first marriage in addition to some things I thought didn’t work from his perspective.”

She also pointed out the clearest way to know when your professional and personal lives are out of whack. “If you feel like you are way out of balance in terms of your work versus personal life, you need to look at your personal life and see if you’re gravitating toward work because you’re not happy in your personal life. And you’ve got to fix your personal life. It’s not going to get better by just consuming yourself, just totally getting so into work,” Senator McCaskill continued. “What I found myself doing, rather than the hard work that is required in a marriage . . . was just saying ‘Well, I’ve got to work,’ or ‘I’ve got this big job. I’m the elected prosecutor in Kansas City. I’m running all this office—I’ve got all these felonies!’ And I just pulled myself away and justified it because of all the work I had to do. And I think men historically have done this a lot. If things are out of balance, then examine your personal life and make sure that you are in a good place, that you are happy there. . . . If you’re not happy at work, you’re going to want to stay home. If you’re not happy at home, you’re going to want to stay at work. So if you are going to get a balance, you’ve got to be happy both places.”

Senator McCaskill’s story made me sad. Like Judith Rodin, the senator had pointed out that her dedication to her career had, in important ways, negatively impacted her marriage. She had ducked out of her relationship to focus on work, when the marriage seemed too difficult to face. As so many women seem to do, she brought up the subject of “balance,” but to me the question of how to integrate one’s professional and inner lives is not so much one of balance. Powerhouse PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi—who you will read more about in the next chapter—believes that the key to her successful thirty-five years of marriage has been her ability to compartmentalize the many sides of herself. She has subtracted part of herself from the home equation, trying not to bring her work self past the garage. Her version of “balance” seems to be keeping the different parts of her life separate . . . and it actually appears to be working. Yet I think balance is a bourgeois illusion, one that is marketed to guilty, over-stressed working women who cleave to the idea that an even, bump-free life is available to them if they would only buy these yoga clothes or microwave this frozen meal or take those meds.

You may not have read it here first, but consider this the last word on the subject: there is no balance. You will have to make significant sacrifices, so make your peace with it. Knowing that early on, as a young woman—or as an entrepreneur whose life is, by definition, full of work-life trade-offs—is vital if you are going to build a truly successful life. To me the question of how to do that is one of knowing yourself, of wrapping your mind and spirit around the value you bring to the marketplace and the value you bring to your personal life. Being able to articulate and to embody both is the essence of growing your overall brand—the whole package that is your life.

“YOUR” MONEY

According to our poll, four in ten (39 percent) female breadwinners say there is more tension in their relationship because they are the primary earner, compared with one in five (21 percent) male breadwinners. One in five female breadwinners (19 percent) reports that being the primary earner has had a negative impact on their marriage/relationship, compared with only 5 percent of male breadwinners. Three in ten female breadwinners say they have had arguments with their spouse/ partner over the balance of power in their relationship. One in six says that it has threatened their relationship.

My husband and I have never argued about the balance of power in our relationship since my raise. The less we talk about work, the better. The only person I can talk about power dynamics with is usually only another woman in my position, one who also makes more money than her husband. Because that woman will understand—even if it isn’t the case in her own relationship—she’ll get it. No one wants to touch it for fear that the whole apparatus will crumble apart on impact. I think it’s probably true of many breadwinning women. And because of that, I agree with Judith that it’s natural that many find themselves slowly growing apart from their mates because of the demands and realities of their actual careers. But for me it’s the financial piece that makes me nervous. I was not prepared for that. And again, it was my own issue with it that caused these problems—the guilt I felt about it, the guilt I felt about what it took to get there, the sacrifices I made at home to advance my career, my salary, and my children’s future.

Of course, as an educated, career-oriented woman, I always aspired to bring home the bacon. I loved the concept of being able to provide for my family. But I did not think, when I surpassed my husband in numbers, that it was going to mean living with so much loaded silence around the issue. I think many of us live this way. I know my experience is probably a bit more public and exaggerated version of what many women feel like when their earning capital exceeds their husbands’, but the net result is the same. It’s a power shift that I don’t think anyone in the household is ready for.

Certainly we weren’t. Almost right away the language changed. When he made the bigger salary, we used to talk about “our” money; our combined income was a marital asset. When I started making more, Jim started referring to it as “your money.” It just happened. He never stormed in one evening and growled, “This doesn’t work for me, you pulling in more money than I do. I feel like this is not ‘our’ money; that’s your money, and I will not be made to feel inferior!” He would never dream of doing or saying anything even remotely like this. I’m sure if I were to ask him if he did, in fact, feel that way or something along those lines, he would say it was ridiculous.

Yet the money conversation has changed. I still think of our money as a marital asset, but if, for example, he wants to buy something, he’ll seem guilty and say, “I don’t want to take your money.” Whenever we’re thinking about making a big purchase or taking a trip, Jim will say something like, “I’m not sure if we should spend so much of your money on that.” That little shift from “our” to “your” has had a tectonic effect on the balance of power in our relationship, the way our household is run, and the way we communicate.

It’s evidently not too loaded for other women to talk about, though. “I am responsible for all the bills. Because of that, I make sure I make all the decisions about the household, and he doesn’t like that, so that causes some friction,” reported one woman in our poll. When I read that, I could feel my heart pop like a soap bubble. That’s not Jim and me—right? Having said that, Jim would say—and has said—that I have changed as a person, while I, however, always looked at it as growing and securing our family’s future. We may both be right. It doesn’t seem fair, but we definitely may both be right.

A LITTLE BIT LIKE A PARTNERSHIP

Incredibly, for some couples money and power dynamics just don’t seem to matter all that much. Being a breadwinner, no matter who it is, makes for a more relaxed dynamic in their relationship. To be clear, such people represent a minority: in our poll only 8 percent of female and 24 percent of male primary earners say there is less tension in the household as a result of them being the breadwinner. And you can feel the lack of tension from the laissez-faire tone of their comments, verbatim from our poll. “As long as we have income coming in, it doesn’t matter who’s making more,” said one woman. From a woman grateful to have fewer fights with her spouse over money concerns: “My becoming the primary earner has meant more money for us overall, so finances are less tight. Less financial worries equal less tension.” One reported a benefit: “The household duties are now done by my partner with no complaints, and I don’t have to deal with the stuff that I don’t like to do.”

Any one of these comments could have come out of the mouth of Dee Dee Myers, who was White House press secretary during the first two years of the Clinton administration and is now executive vice president for Worldwide Corporate Communications and Public Affairs at Warner Bros. I was talking to her on the phone from her (then) new home in LA when, curious, I asked her how it felt for her to be her family’s primary earner.

I could practically hear her shrug. “I don’t think about it very much, and I don’t think he really cares,” she said. “In the course of our marriage we have sort of traded back and forth, depending on who is doing what, and how flexible one is versus the other, depending on what’s going on. That’s always worked really well for us . . . [and] Todd does all the cooking.”

Wow. I hinted that it wasn’t going so easily for me, maybe because I was a newbie. “I sometimes feel guilty about it,” I said. “I don’t know why. It’s kind of a weird, new thing for me. Sounds like you guys have always had an evolving [breadwinner status].”

Dee Dee thought about it. “No, I think we always look at it a little bit like a partnership, almost like everything goes into the partnership, and some of it is monetary, and some equity . . . and Todd makes my life so much more interesting. How do you put a value on that?” she mused. “You know what the other thing is? Neither of us cares that much about money. We are responsible with that money, but we have never had a fight over money. Not once.” And they’ve been married almost eighteen years. What in the world was their secret?

Again I could almost hear the shrug. “[My husband] just doesn’t really care. He doesn’t need a lot. Like, it would never occur to him to buy an expensive car. He drives the minivan. And I drive an SUV,” Dee Dee said bluntly. “He’s much more interested in things that have historic value as opposed to monetary value, that have an emotional value . . . like the art projects that he made in third grade.” Dee Dee said that, of course, they talked about moving, selling their house, buying a new one—that sort of thing. “But it’s never, ‘You can’t spend this much money on a pair of shoes,’” she said. “Or . . . ‘You can’t buy a first edition of the Great Gatsby.’” And there it was. I couldn’t believe it: the subject of money was emotionally irrelevant to them.

But it turns out there are those couples who one-up people like Dee Dee and her husband: they’re actually happy with the wife being the breadwinner.

WE COMMUNICATE MORE EFFECTIVELY

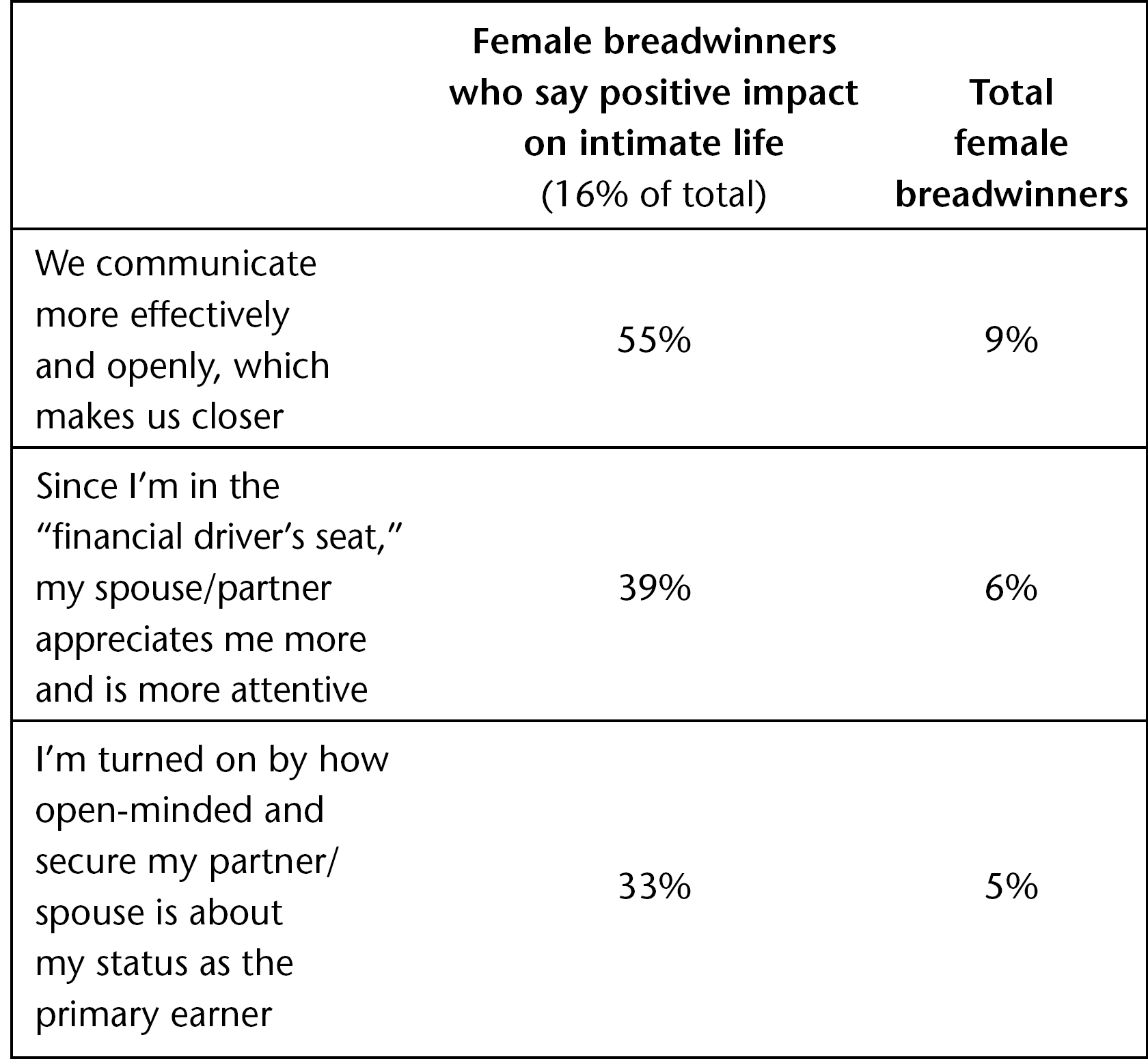

According to the MSNBC Working Women Study poll, although female breadwinners are less likely than male breadwinners to believe being the primary earner has a positive effect on their relationship with their spouse/partner, there is a small minority of women—16 percent—who report that it has been great. For these women communication and work-life balance with their partners has actually improved since they became the household breadwinners. Also, perhaps because there is generally less tension in households where money isn’t scarce, our survey reports that female breadwinners with higher household incomes are more likely than those with lower household incomes to say they enjoy being the primary earner (43 percent household income $75,000+ versus 33 percent household income under $50,000). Specifically, these women are more likely to express positive sentiments such as “content” (54 percent women with household income $100,000+), “emotionally secure” (51 percent), “financially secure” (58 percent), and “empowered” (44 percent).

Consider this chart from the poll on that 16 percent:

Reasons being the primary earner has had a positive impact on intimate life (asked of those who said very/somewhat positive)

Certainly I have a lot to learn from this small but incredible group of women. Maybe many of us do. Somehow they, and women like them whom we didn’t get to poll, have managed to construct lives in such a way that their success at work isn’t interfering with their relationships. In fact, it’s just the opposite: it’s apparently enhancing them. Read this comment from a primary-earning woman, verbatim from the survey: “I feel a sense of accomplishment and pride, especially in today’s world. That said, it’s always a team effort, regardless of the income.”

These women seem to have hit the sweet spot where their professional value and inner value grow in tandem. Who in the world are they?

Bobbi Brown, cosmetics mogul, for one. It came up during our conversation about growing your value. When I asked her whether she was married, Bobbi replied that she was. “I am happily married,” she said. “Happily married for twenty-six years.” I did a verbal double take: “Did you just say happily?” She confirmed. “I did. I am happily married. I adore my husband.” She gave some sweet background. “My husband has his own business—he’s a real estate developer and an attorney,” she explained. “And now, especially since my kids are getting older, we remember why we actually enjoy being together. We like the same things.”

I love hearing happy endings like this, and I want that for myself. But I wanted to know from Bobbi whether hers was the result of hard work in the marriage, especially as her business grew. “Did you experience any challenges when your career took off?” I asked. “The answer doesn’t have to be yes.” But Bobbi was emphatic. “Absolutely! Absolutely. There’s always challenges [sic], and for me, personally, figuring out how to balance was really difficult. The truth is there’s no such thing as balance. But my husband was really helpful when I was overloaded and exhausted and kind of freaked out that I had to travel to promote my business or be at certain events,” she said. “He would say to me, ‘Stop. Breathe. Think about what you’re doing. You don’t have to do everything. Do it your way and do what matters.’” And what had really mattered to her? “Our family always mattered more than being at every single event,” she said.

What a powerful example of a life in which professional value and inner value dovetail beautifully! And it was clearly the dynamic between Bobbi and her husband that had, in large part, made that life possible. But how, I wanted to know, had he responded to her ambition? “Well, we started the brand together. When we started the brand, I was a freelance makeup artist, and he was in law school. We started together with just ten lipsticks,” she recalled. “We never thought about the big picture. We certainly never thought about where it would be today. We always just thought about what is. That’s how I’ve always lived my life, and I still do actually.”

PROVIDER PRIDE

Not really thinking about who is making more money. Not looking at the big picture. Going with today. These are the modus operandi of a couple of very successful, ambitious women who make more money than their husbands. It makes me wonder: Am I creating these problems around money and power with my husband? He’s never been anything but supportive of my career; maybe he really just wants to see more of me. Is it possible that this is all in my head?

I had a revelation about this talking with Glamour editor-in-chief Cindi Leive about her feelings about being the breadwinner in her household. Cindi had clearly done some thinking about it. “It took me a while to really be able to have what I think of as ‘provider pride’—you know, that feeling that I am actually doing something positive and wonderful for my family,” she said. “And of course, when you say it objectively, you know, it’s like, ‘Yeah duh . . . of course you are going to be proud of that.’ But I think for a lot of women it feels like something selfish. You have to be able to bask in that. To be able to do that in this economy as a woman or a man is a great thing.”

Selfish. Bask. I wanted to unpack those words and the thoughts behind them. I felt like I was going to get the key to something resembling an answer. “And do you let yourself bask in that? Do you feel guilty?” I asked. “Because I have to say, for me, it was a really weird transition and a weird power that I did not expect or actually . . . want. I don’t know if ‘power’ is the right word, but all of a sudden everyone in my family turned to me for every decision. Is your advice to . . . expect that that could happen in your life? To be ready for that? How do you make it work?”

Cindi was philosophical. “I guess that my first advice is marry somebody who would be as psyched about [you being the breadwinner] as you would, and I guess that is easier said than done. But I do feel like fundamentally, if you’re in a relationship with someone who is grudging about your career success or feels that it comes at the expense of their own, I think it’s probably hard to overcome that,” she said.

(On reflection I have to say that although I do agree with Cindi that women need to figure out whether they’ve got the right partner before the wedding or otherwise life commitment, I don’t think you can always tell by what a potential life partner might say to you about his feelings concerning salary inequity. I do, however, think that it’s essential for women to be very clear with themselves as well as their love interests about who they are and what their intended trajectory is—and to not soften their ambitions to make themselves or their partners less insecure. Tell the truth to your partner and to yourself. It only backfires if you don’t, because it’s basically impossible to squelch your true nature.)

“My husband, I guess, he’s just always been very fully accepting of it. And he’s been proud of me, so then it’s easier for me to be proud of myself,” Cindi said.

I thought about that for a moment. “My husband is too. I think sometimes it’s in our heads,” I said. “I love your advice. Bask in it. Have provider pride.” Maybe my needless guilt over making more money had made me think there were problems in my marriage because of it! Maybe in this case I am the one standing in the way of merging my professional value and inner value. Maybe it’s closer than I think.

And that may be true. But there is a group of people whose feelings, without question, can become very real, very complex, and sometimes very angry as a result of any professional woman’s ambition and hard-earned successes.