“BUILDING A BRAND AROUND IT ALL”

How Successful Careers and Moms Work

Glamour editor-in-chief Cindi Leive was due any day with her second child and still happily working full-time at the magazine when she had a flash of exhilaration. “It was a good moment for the magazine, and we won a couple of really big awards,” she told me. “And I just remember feeling incredibly lucky and blessed that I could do that and also be nine months pregnant. And it sounds kind of corny, [but] I do look back to that moment, and you know, it just makes me feel incredibly lucky and blessed to be a woman at this moment in time.”

Cindi glows with what she calls “provider’s pride.” She loves her hard-driving job, she loves her family, and she feels great about her life. “Because of how hard I work and how hard I’ve worked, I’m actually able to give my kids good educations, to have a nice place to live, and to keep our family happy and afloat,” she explained. She doesn’t feel uncomfortable about being her household’s chief breadwinner. “I think if anyone is making a good enough salary to allow the other person to work part-time and spend more time with the kids in this economy, that’s a good thing,” she said. “That is not anything that anybody should be complaining about.” She does feel sad about missing the occasional school event or morning drop-off. But she also loves her job. “And I think also it doesn’t mean you’re never going to feel guilty. I think any responsible parent feels guilt sometimes on some level: you always want to be with your kids,” she reflected. “I think it’s fine to feel guilty. It just doesn’t mean you have to go and totally change your life.”

There you have it: a happy, hard-working mom. They’re out there in droves, these happy, hard-working moms. I told you in the last chapter that we were going to get around to the good news in this chapter—and here it is. According to our poll, agreement is consistent across all age groups and household incomes: most breadwinner moms feel pretty good about their lives. Sure, they recognize the complexities of being a working mother and the potential downsides it has on relationships with their spouse and kids. As discussed in the last chapter, poll results and experience certainly show that breadwinner moms are subject to the full spectrum of emotions and parenting potholes that all those remarkable women and I shared about. Perhaps you have them too, which may be one of the reasons you’re reading this book.

But still, our survey results show that many of us are not just surviving but prevailing. When asked to characterize how they feel overall about providing for their families, breadwinner mothers are more likely than female breadwinners without children, for example, to say they feel “proud” (50 percent moms versus 32 percent non-moms), “content” (45 percent moms versus 34 percent non-moms), “emotionally secure” (40 percent moms versus 31 percent non-moms), “financially secure” (40 percent moms versus 30 percent non-moms), “empowered” (37 percent moms versus 28 percent non-moms), and “relieved” (27 percent moms versus 19 percent non-moms).

“It has taught me to respect my spouse and kids more for what they do for me at home, as well as outside the home.” That is a verbatim quote from one of the breadwinner moms interviewed as part of the survey conducted for this book, responding to the question of how she feels being the primary earner in her family’s household. Here is another one, speaking on the same issue: “I think that it teaches my daughter that she can take care of herself, and she does not have to necessarily depend on a man to take financial care of her. That she, too, can have a career and family.” This is one I particularly like: “It is all about balance. Both parties in the relationship need to understand the role each plays. Money is not the only asset a person can provide to a family.” And as one mother summed it up: “It’s a good problem to have, all things considered.”

Is it possible to have it all? According to our poll, yes, with 78 percent saying they are successfully able to manage work and family. For women in the northeast United States, the number is even higher: 87 percent of breadwinner moms agree. Consider this chart, pulled from our poll data:

Agree “It is possible to ‘have it all’—meaning being able to successfully manage work and family”

They’re not just having it all either—they’re having more. According to a 2013 Pew study, the total family income is highest when the mother, not the father, is the primary provider among married couples with children. In 2011 the median family income was nearly $80,000 for married couples when the wife was the breadwinner—about $2,000 more than it was for couples in which the husband was the primary breadwinner and $10,000 more than for couples in which the spouses’ earnings were basically the same, the study reported.

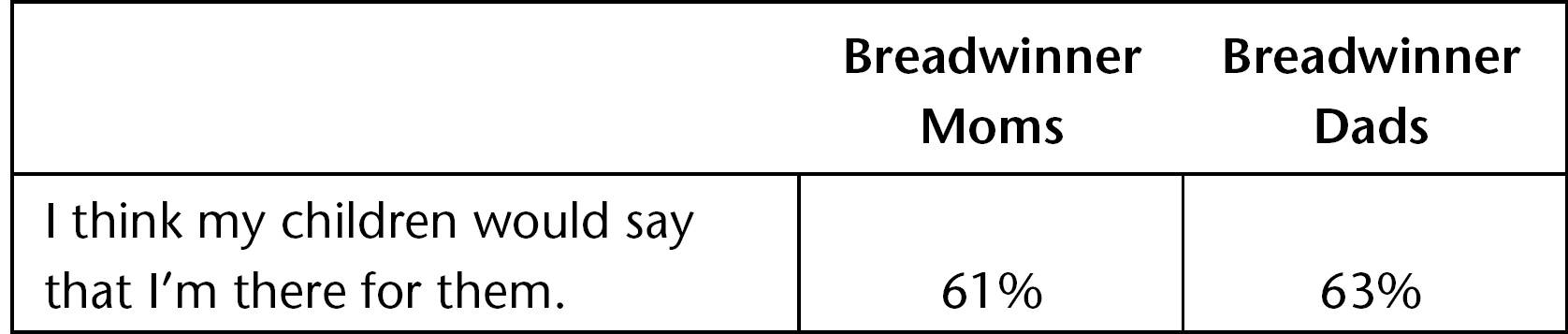

Moreover, most female breadwinners also believe that they’re close to their kids and that they’re good moms. Fully three in four (74 percent) in our survey agree that their relationship with their children is “as perfect as perfect gets,” and six in ten (61 percent) concur with the statement, “I think my children would say that I’m there for them.” (By the way, according to a 2013 Pew Research study, mothers give themselves somewhat higher parent approval ratings than do fathers, with 73 percent of mothers saying they are doing an excellent or very good job, compared with 64 percent of fathers. In addition, working mothers give themselves slightly higher ratings than nonworking mothers for the job they are doing as parents; 78 percent and 66 percent respectively. I told you there was good news on the flip side!)

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), junior senator from New York, believes that the main reason she and her husband are doing a pretty good job of raising their two young sons is because her job has built-in flextime, a luxury most of the country’s mothers don’t have, she pointed out. “I have a lot of flexibility. One of the things I have that the woman who is going to work in this restaurant, the woman who is going to clean it after hours—they don’t have flexibility,” she said in our meeting at a restaurant in New York City. “They are given hours; they have to work their hours. They might not have sick days. They may not have vacation days. So their challenge of raising their children and doing their jobs is much harder than mine. Mine is a billion times easier because, for example, if I have a sick child, I can bring my kid to work with me. If I need to limit meetings before 9 a.m. so I can take my kids to school, I can do that because I set my own schedule. So yes, I have a juggle that is not dissimilar from a lot of working parents—you know, getting out the door with lunches made, breakfast fed, teeth brushed, soccer uniform in the bag. That’s the juggle we all face every morning.”

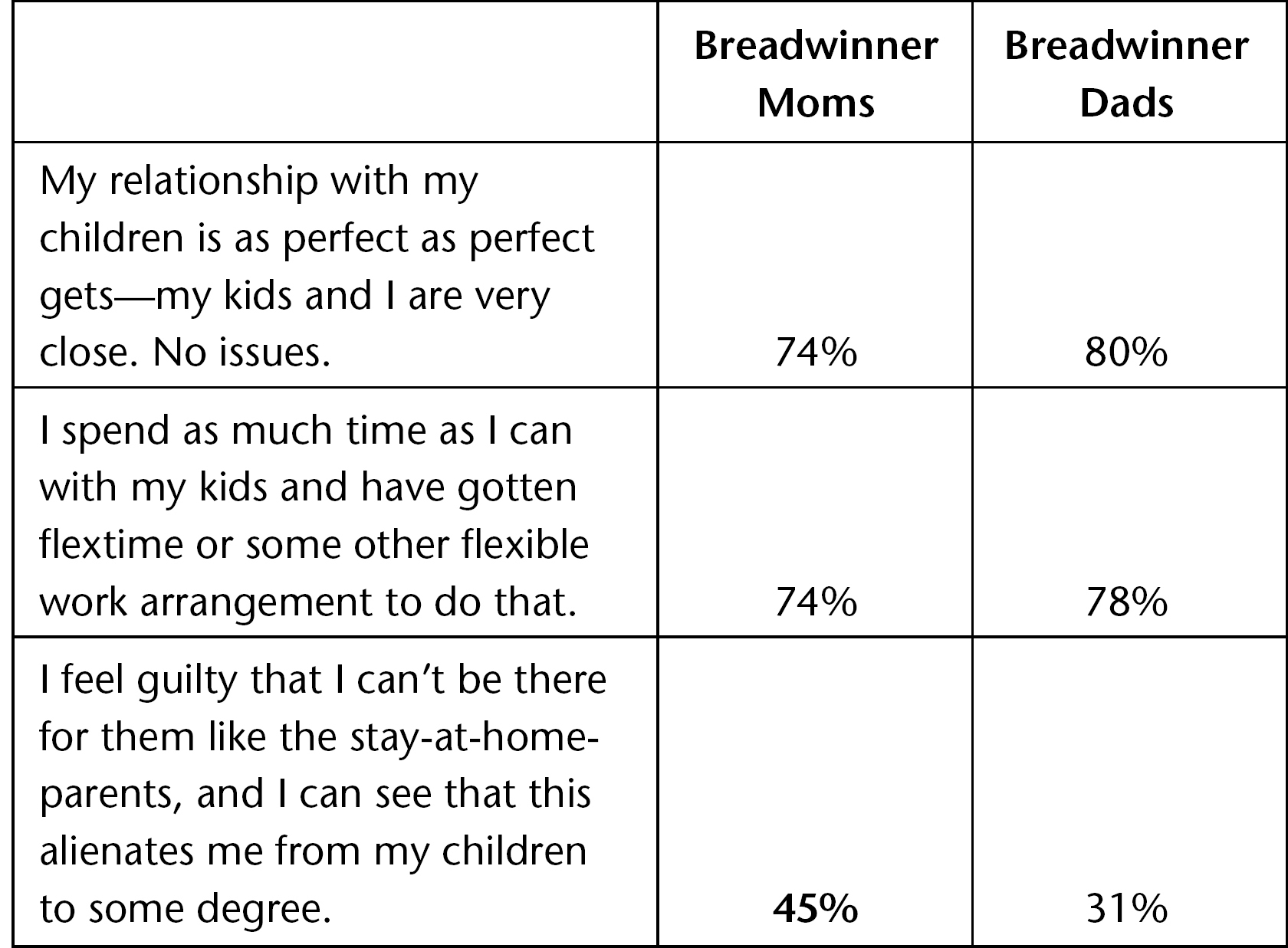

Perhaps in part because of flextime, more than one-third (36 percent) of breadwinner moms report that being the primary earner has had a positive effect on their relationship with their children, compared with half of breadwinner dads (52 percent). Here’s the data, pulled from our survey:

Parents say statement applies to them:

Parents strongly/somewhat agree:

But to me one of the most interesting statistics from our poll is this: those breadwinner moms who enjoy being the primary earner overall (57 percent) are more likely than their peers overall to say their career has had a positive impact on their relationship with their children. That is, if you like being the main provider for your family, you’re going to feel as though your professional life enhances your children’s lives more than a mom who, say, either feels neutral about or doesn’t enjoy that role. It seems that if you like what you do, your enthusiasm will spill over into your mother-child connection.

This is what I’m talking about when I say that the closer your professional value overlaps with your inner value, the more you are going to feel more successful in your life as a whole. Those women who are as passionately, joyfully ambitious for their careers as they are for their personal lives to flourish aren’t just managing a job and a family successfully—they’re loving it, warts and all. Just listen to Claire McCaskill.

HOME HAS BEEN A GROUNDING THING

Senator Claire McCaskill was at work, she said, when the texts started coming in. The messages were seriously challenging her position on two votes in the Senate that had come up that week: one on national security issues, relating to the government’s ability to collect information on Americans, and the other on the Keystone Pipeline. The senator had to stop, ground herself, and think carefully about the reasons why she had voted the way that she had before texting back. She had to be on her game. After all, these provoking texts weren’t from her typical constituents; they were from her kids.

This is one of the stories Senator McCaskill shared with me during our interview for this book, and I love it. It’s a perfect example of how a professional, working woman intertwines her professional value—that of a tough-minded, judicious lawmaker—with the part of her inner value as a mother, thriving on the connection with her children. I learn by listening to the experiences of women like Senator McCaskill because I’ll be the first to admit that it has been hard for me to integrate motherhood with my professional life. I’ve taken my daughters with me on work trips, but they’ve often ended up feeling alienated because I always have to spend so much time working. Plus, I don’t think seeing me in my “always-on mode” is ever an especially welcome experience as far as they’re concerned. It’s as though I become the “other mother” who reeks of phoniness, manic stress, and probably grandiosity—the one who takes their actual mommy away. I noticed recently that, when I am in crowds, my daughters will scream out, “MIKA!” to get my attention—insinuating that “Mom!” does not work. But the way Senator McCaskill has responded over the years to her children cast a whole different light on how that particular friction with your kids—when your professional life grates against them—can actually bring you closer together.

“I have . . . raised my children to argue with me, and that has been helpful,” Senator McCaskill explained to me. “Nothing has been more grounding than coming home and one of your kids calling you out on something you’ve said or done that they think is phony. They have been a tremendous focus group for me, especially as they’ve gotten old enough to kind of pay attention to positions I was taking and things and people I was endorsing.”

Rather than feel like curling up into a ball and rolling away (as I am wont to do) when her kids take her to task for posturing in an insincere way, she appreciates their feedback, even if it’s tough. She relies on her kids’ interest and investment in her decisions as a lawmaker—and as their mother—to help root her to what matters. “I can take people being upset with me about votes. It’s very hard when my children are pushing back, and I have to be really prepared with my arguments. So home has been a grounding thing for me, particularly once my children got beyond their midteens and started really being thoughtful about things and saying, ‘Really, Mom? You’re full of it!’”

This was amazing stuff to me. That this high-powered, highly visible mom and her children can have thorny discussions about complex political, emotional, adult topics—with everyone coming away feeling the better and stronger for it—said a lot about the trust, respect, and love undergirding their relationship. Senator McCaskill had not only shown her children that she had great passion for her work and impressed on them her belief in public service; she had also always invited them to engage with her on whatever issues of the day she was mulling over, decisions she had made first as a prosecutor and, later on, as a member of the US Senate. Ergo, her kids, by and large, apparently felt included in her career rather than separated or barred from it.

Senator McCaskill’s example proves what the statistics on the women in our poll suggest. If you love what you do as a breadwinner mom, that passion can have a positive effect on your relationships with your children too. And if you value your work, you’re more likely to value the positive connections with your children. Says one New York book editor: “One day when I was working, and my daughter wanted me to play with her, I described the novel I was editing. Then I asked her to draw her concept of what the book cover should look like—it’s still on my wall. It was just a tiny way to make her feel involved.” That’s the Venn diagram of overlapping professional value and inner value. That is the kind of success I’m talking about.

But no one is born knowing how to do this dance. To a certain degree you have to watch it first. Senator Gillibrand, for one, found out about how to get what you want from life by watching role models and listening to mentors—from her grandmother, who founded the Albany Democratic Women’s Club, to Hillary Clinton. “I had good role models. I had my grandmother who taught me to not be afraid, that public service was a calling—that fighting for what you believe in is something worth your time, that women’s voices can really make a difference,” she said to me during an interview for this book. “And I learned from my mother that, you know, being different is okay. You don’t have to be like everybody else. You can aspire to be a senator. You can aspire to be a congress-woman. You can aspire to take on the Department of Defense if you want. You really can do these things differently if you believe in it.” She emphasized, “I also had great mentors. Having the women of the senate like Mary Landrieu giving me guidance; having Hillary Clinton helping me every step of the way when I was deciding whether to run and what it would look like.”

Senator McCaskill feels the same way. Rather than taking the credit for modeling for her kids the importance of civic engagement, she credited her own mother for doing the same for her as a kid. “I was just blessed with a mother who spoke out and said what she thought just about all the time, so I had a terrific role model,” she said. “My mother used to say things that I found incredibly embarrassing when I was twelve years old. When I was thirty-two years old, I realized how much she was helping me by role modeling, that by taking the safe route and not expressing how you really feel and sublimating what you feel and being so worried about what other people think of you, that you’re paralyzed—that you lose out a lot in life.” This was a mother who was not afraid to be authentically herself in front of and with her daughter. She wasn’t afraid that her daughter wouldn’t love her if she spoke out. She had clearly passed on her sense of fearlessness, of confidence to her daughter. And her daughter—while appropriately, tweenagerishly embarrassed—hadn’t felt intimidated by her mother but rather had felt a grudging admiration for her that, over time, blossomed into gratitude. Indeed, she had modeled herself on her mother’s behavior.

If you didn’t have great role models, adopt those of the successful women in this book!

Or try building your own. It’s what I’m trying to do too.

YOU CAN’T LEAD WITHOUT MAKING SOMEBODY MAD

Hearing about other women’s role models makes me reflect on my own background. I was raised with my opinionated statesman father and my artist mother debating current events and politics around the dinner table. All three of us children were expected to dive in at will. My older brothers had never had any problem standing their ground, but I hadn’t always been confident enough to put myself out there. In fact, I was reluctant to share any of my opinions for fear of losing face and of being criticized by my outspoken family. Sure, my parents had both modeled for me the importance of being engaged with matters of the world and that, if I could hold my ground, I was an equal. But I hadn’t felt like an equal; instead, I created a role for myself in order to hide from the family intellectual roughhousing—and potential shaming. Instead of taking a risk and being vocal, I became the masterful party hostess, the dinner table diplomat—in other words, the affable, intelligent news show host.

How does this play out in my relationships with my own kids? Have I been playing out some version of my old family drama around the dinner table, keeping the critics at arm’s length by lacquering over my true self and with a candy-glazed persona? Somehow trying to protect my children from my professional self and life, by thinking I have to be two people, that my professional value and inner value could not possibly mix at home? When I am trying to pull off my impression of a sis-boom-bah mom bursting with strained bubbly optimism and sugary fretfulness, it’s as though I am deliberately trying to hide the part of me that is ambitious, aggressive, high achieving and hard working in a dark closet. Am I my own worst enemy? Am I too chicken or eager to please to open that closet door?

My conversations with all the amazing women in this book have helped open my eyes to the possibility that I—not my work life or family life—am creating my double life. Unconsciously I am pushing my family away from the outspoken, ambitious part of me in a bid to escape their criticism and disapproval—and to fend off their rejection if I try to connect with them in an honest and loving way—by putting up my time-tested party hostess defense.

My fears around not being able to be both a real professional who wants to be taken seriously and a real mother who wants to be loved are valid. Everyone’s are. I think we working mothers all have fears around integrating our professional value with our inner value, about unfurling the sum total of our complete personalities in our family’s presence. There is something that keeps us from integrating all the passion, drive, and sense of mission we bring to our careers and to our private lives. I have it in my head that my family hates it when I’m working my professional value, that they associate it with a bad acting job, showing off, and an overwhelming work drive. But maybe one of the reasons they hate it is because I almost never bring my Morning Mika self home with me, so it seems like some far-off bigwig boss rather than part of the “real” me.

Or maybe we’re a little like Rockefeller Foundation president Judith Rodin, so concerned that family life will erode our professional value that we feel extremely protective of our work lives and personae. Or maybe we’re more like PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi, self-conscious about our executive power at work when we’re at home, so we feel we need to check our crowns at the front door or in our family’s presence in any setting. Because we don’t want to be accused of throwing our weight around at home, and because we’re scared that any parental response will be judged as such, maybe we just keep quiet rather than risk being resented.

But that’s not what our family wants either. Maybe they sense that they’re not getting all of us, the “real” us, and therefore it causes cognitive dissonance for everyone. Maybe, like Senator McCaskill, we can learn to take the heat as well as the love that our children bring to us—and build the courage to bring our whole selves to the breakfast and dinner table. Or whatever works for you: the Skype session when we’re away for work, the back-and-forth texting about whether you’re willing to let your daughter have a sleepover that night, talking with our children at the interminable line at the market or in the car on the way to work and school. Whatever our professional bona fides and personae are, we need to integrate them with our personal lives wherever we go. It’s a healthy alternative to people-pleasing and feeling like a fake all the time—and distancing ourselves from our personal lives in the process.

This reminds me of something else that Senator McCaskill said during our conversation when the topic turned to the subject of people-pleasing. “All of us have the need to please, but the need to please can become paralyzing,” she explained. “In a way a political career is great for that because the longer you do it, the more you realize you can’t make everyone happy. In fact, you can’t succeed unless you’re making somebody mad. You can’t lead unless you’re making somebody mad. It’s impossible to lead unless you’re making someone mad. . . . I just can’t do it and please everyone. And if you do, you just fail, because everybody sees you as the phony waffler that you are, trying to please everyone.”

She was, of course, talking about her career on the Hill, but to me she could just as easily have been describing my life as a working mother. As I’ve described, I’m always feeling incredibly guilty and anxious where my kids are concerned, so when they criticize me, I become the mother of all people-pleasers. And the people I’m trying to dance hardest for are my daughters. It’s understandable that my children wouldn’t want to interact with that cloying, people-pleasing mom. Maybe they see me for “the phony waffler” that I am, so remorseful about the demands of my job that I’m too afraid to make them mad—by claiming my role either as Mom or in a career that I love, even if it takes me away from them on trips and evenings. Maybe I’m too scared to tell them clearly and honestly that I love them all the time, wherever I am, even though I’m missing important events, and to hear what they would say in response. I’m afraid they won’t love me. Or, worse, that they already don’t.

But perhaps the real problem is that I am too chicken to trouble the waters by finally acting like the woman I am—a mother, journalist, movement builder, all of it—in front of and with my kids. When, in fact, maybe being authentically myself with them could be the best thing that’s ever happened to our relationship: supercharged by ideas, cultural trends, news; excited by the opportunities for women; and being honest about the challenges we all face but don’t talk about. These are my challenges and those that my girls will face some day too. Being open with them about who I am, what I have done, what I am proud of, what I regret, what I am still working on. Being myself.

Perhaps this is true for many of us. Maybe the fear and the guilt have to stop. Perhaps we’ve got to embrace our professional value—to be honest about our power on the job and in the marketplace—and express it to our children and families at home with the same sense of excitement, drive, and confidence we feel when we’re at work. Maybe we should let them know that our mother-child bond with them is even stronger than our careers and makes us who we are—at work, home, and in life overall. Perhaps we’ve got to get over the idea that there’s something wrong with being an ambitious mother. Maybe we should stop thinking that we’re doing something bad to our children by being passionately engaged in our work. Maybe the “problem” is in our heads.

Or is it? Does a mother’s career harm her kids in any objective, calculable, testable way? That is, what exactly have the big brains in the field found about the impact on children of their mothers’ working?

A SENSE OF THEIR OWN VALUE

Ever since women started entering the US workplace in (low) double-digit numbers in the 1950s, the American public has been arguing, extremely divisively, about how their mothers’ working affects children under eighteen. Even though the labor force has changed dramatically over the years, our society still has a tough time wrapping its collective head around whether Mom being gone during working hours is acceptable for children’s development and well-being.

The majority of mothers work for a living (71 percent, according to a 2014 Pew Research report), and the majority of married couples with children in the United States both work for a living (59.1 percent, according to the 2013 Bureau of Labor Statistics), and the percentage of all mothers with children under age eighteen was 69.9 percent in 2013. And as mentioned earlier, only 16 percent of Americans believe that the best thing for children is for mothers to work full-time. According to the Pew report, 60 percent feel that the best way to raise a child is to have at least one parent at home, full time, whereas just 35 percent say it doesn’t matter whether parents work or not.

But on what are people basing their beliefs? What’s the evidence that mothers working for a living is bad, good, or indifferent for children? How would it even be measured?

Sixty years of studies on the subject has confirmed at least one fact: researchers must test for a great deal more than simply whether the mother works or not if they want accurate results. There are too many other variables in families that shape children’s intellectual and social aptitude, most importantly socioeconomic class, whether a father is living at home, whether the mother works full- or part-time, the child’s gender, and more. Another consistent finding over the years has been that mothers’ working and its effect on kids is largely relative to the cultural norms of the day. For example, a few early studies in the late fifties and sixties found that grade school sons of middle-class working mothers had poorer school performance and lower IQ scores than the sons of stay-at-home mothers. Decades later, in the 1980s, three separate studies revisited the middle-class mother-son relationship to maternal employment and boys’ lower performance.

This time two studies out of three didn’t find any difference in school performance and IQ between the working and stay-at-home moms, but the third did find lower IQ scores for sons of working middle-class moms. Why the different results? Researchers have a number of hypotheses, among them that in the 1950s and 1960s working mothers were socioeconomic abnormalities, creating a stressful environment for their children at the least on the societal front—if not also financial—because their home lives were different from the majority of their children’s peers’. Boys in particular might have been vulnerable because their male self-image might have been impacted by their fathers not providing enough for the family, for example.

But in 1999 a landmark study was led by University of Michigan psychology professor emerita Lois Wladis Hoffman, PhD, and her team. Hoffman published a study whose objective was to retest all previous major findings combined. With a heterogeneous sample size of four hundred families in the urban Midwest, Hoffman’s team factored in all the known variables that influence results, but they also tested for new, important contingencies—that maternal employment influenced the mother’s sense of well-being, the father’s role, and parenting styles, all of which, in turn, influenced the child.

The findings were fascinating. First, the question of whether mothers’ jobs hampered boys’ performance and cognitive abilities was put to rest. Indeed, the Michigan study reported the opposite, finding that the children of working mothers actually earned higher scores on the three achievement tests for language, reading, and math—across gender, socioeconomic status, and the mother’s marital status—even controlling for the mother’s education. Indeed, it was one of the strongest findings of the study overall. But they found more.

Previous research had inconsistently found that daughters of working mothers were, for example, more independent and scored higher on socio-emotional adjustment tests but that results for sons was a mixed bag, dependent on their social class and age. The Michigan study now reported that teachers consistently rated employed mothers’ daughters, across the board, as being more positively assertive (engaging in class discussions, asking questions when directions weren’t clear, at ease in leadership positions), less disruptive, and less likely to act out than daughters of stay-at-home mothers. Moreover, they were more independent, less socially awkward, and had a higher sense of their own value. In both one-parent and two-parent families, working-class working mothers’ sons also showed more positive social adjustment when their mothers were employed, although middle-class boys with employed moms acted out more than the sons of stay-at-home mothers. Researchers speculated that these boys might have had less supervision than their working-class peers and were, thus, more likely to engage in comparatively unruly behavior. That is, in working-class homes someone was looking after the kids—a grandparent, an aunt, an uncle—whereas, in middle-class homes adults were either working or simply not around, so those boys were among the tribe of latchkey kids left to their own devices.

Another finding was that sons and daughters of working mothers have less traditional gender-role perspectives. Researchers asked the children whether or not men could do jobs traditionally considered women’s work (take care of children, sew, teach school) as well as whether women could do traditionally men’s work (e.g., fix a car, climb a mountain, fly a plane). Sons and daughters of working mothers reported that women could do “male” jobs and men could do “female” jobs more than stay-at-home mothers’ kids did. What was more, the Michigan study showed that in households in which mothers work, fathers’ involvement further significantly boosted their daughters’ already higher academic performance and sense of value than those of housewives. Not only did girls have their fathers’ support—which is always correlated to girls’ higher self-esteem and school achievement—but they also had the example of an independent woman as their maternal role model. Double bonus! It makes me wonder whether husbands of working women are more egalitarian in their thinking and behavior, to boot.

As for the effect of working mothers’ well-being on children, the study showed that employed working-class mothers scored lower for depression and higher for happiness and optimism and were more likely than stay-at-home mothers to be firm but fair parents, explaining the reasons for disciplining their children rather than using harsh tactics on one end of the spectrum or allowing children free rein on the other. Interesting, I think, that this is what studies say when researchers observe mothers objectively rather than asking them to self-report. Just think for a minute about what it means that there is such a huge gap between what we think we’re doing and what we’re actually doing. Again, to me it’s fascinating and problematic that studies show that working mothers are doing a far better job of raising smart, confident, happy kids than they think they are. Moms: let’s look at the evidence! We’re not doing half-bad here!

To that point, the study also found that working mothers, compared to full-time homemakers, were more likely to report wanting “independence” as a goal for their daughters and were less likely to say that “obedience” or “to be feminine” were important for their daughters to learn. Interestingly, those mothers who said “obedience” and “to be feminine” were important were more likely to have cautious girls who tended not to participate in classroom discussions and reported a lower self-esteem, whereas those moms stressing “independence” had daughters who showed the opposite effects.

Again, remember Chapter 6, when I cited our MSNBC poll, which reported that working mothers felt more bedraggled overall and guilty about not being there for their kids than the dads did? Objective reporting doesn’t confirm it. It just goes to show you that when women are asked to appraise themselves, they judge themselves inordinately harshly. We feel gutted. We feel guilty. We feel we’re not doing well by our children, that we’re too unavailable to be attentive parents. But research actually shows the opposite: our kids are doing great, by and large. In fact, we may well be giving them a leg up in life because we work for a living. It underscores the aphorism: “Feelings are not facts.”

And there’s more. In the summer of 2014 a comprehensive study of maternal employment and its impact on infants also debunked earlier research, which had reported poor outcomes for children whose mothers had been employed full-time when they were babies. This study, published in the American Psychological Association’s journal, Developmental Psychology, found in particular that kindergarteners from lower-income families who were between nine and twenty-four months when their mothers went to work outside the home progress cognitively and socially as well as or even better than children with stay-at-home moms.

“Most mothers today return to full-time work soon after childbirth, and they are also likely to remain in the labor market five years later, suggesting the employment decisions soon after childbirth are pivotal to determining mothers’ long-term employment,” lead study author Caitlin McPherran Lombardi, PhD, of Boston College was reported to have said, according to an APA press release. “Our findings suggest that children from families with limited economic resources may benefit from paid maternal leave policies that have been found to encourage mothers’ employment after childbearing.”

Therein lies the real problem, the major pothole, for most breadwinner moms. Again it’s the battle between reality and perception, a war that takes place in our own minds. The issue is not that children are negatively affected by their mothers working; the issue is a systemic, socioeconomic one. That is, we need to pay working women more—and that’s the one thing we should be focusing on instead of feeling guilty, Senator Gillibrand told me in no uncertain terms. “One of the biggest challenges most women face in the work force is they’re not paid dollar on the dollar for the same work as men, so the statistics are very troubling. [White] women earn about seventy-eight cents on the dollar. Latinas and African American women earn even less. It means that in eight out of ten families where moms are working, they’re not bringing home their fair share, they’re not having the money they need to provide for their kids, and for the four out of ten households where the mom is the primary wage earner or sole wage earner, you’re really undermining those children’s chances of success,” she argued. “We’re also creating an artificial drag on the economy. If you pay women dollar on the dollar, you could raise the GDP by up to 4 percent. So it’s a huge, untapped economic engine,” she added.

We’re still operating in a sexist, archaic mode, Senator Gillibrand emphasized. “The second thing that’s a challenge is [that] our workplace rules are really stuck in the Mad Men era. They’re stuck in a time when Dad went to work and Mom stayed at home, and that’s just not true for most families. Eight out of ten, as I said, moms are working,” she said. “So we really need to make sure that the support they need and the flexibility they need through their work life is there. And one of the best ways we can do that is through paid leave.”

But there is hope, beyond the Senate and the Hill, that workplace rules will evolve further than Mad Men, that they might even be exploded altogether and rewritten. Or perhaps the rules won’t even be written down. Maybe the rules will be replaced by a fluidity and flexibility that bends to work and life needs.

By Millennials and entrepreneurs.